Myeloma cells express basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), an angiogenic cytokine triggering marrow neovascularization in multiple myeloma (MM). In solid tumors and some lymphohematopoietic malignancies, angiogenic cytokines have also been shown to stimulate tumor growth via paracrine pathways. Since interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a potent growth and survival factor for myeloma cells, we have studied the effects of bFGF on IL-6 secretion by bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) and its potential reverse regulation in myeloma cells. Both myeloma-derived cell lines and myeloma cells isolated from the marrow of MM patients were shown to express and secrete bFGF. Cell-sorting studies identified myeloma cells as the predominant source of bFGF in MM marrow. BMSCs from MM patients and control subjects expressed high-affinity FGF receptors R1 through R4. Stimulation of BMSCs with bFGF induced a time- and dose-dependent increase in IL-6 secretion (median, 2-fold; P < .001), which was completely abrogated by anti-bFGF antibodies. Conversely, stimulation with IL-6 enhanced bFGF expression and secretion by myeloma cell lines (2-fold;P = .02) as well as MM patient cells (up to 3.6-fold; median, 1.5-fold; P = .002). This effect was inhibited by anti–IL-6 antibody. When myeloma cells were cocultured with BMSCs in a noncontact transwell system, both IL-6 and bFGF concentrations in coculture supernatants increased 2- to 3-fold over the sum of basal concentrations in the monoculture controls. The IL-6 increase was again partially, but significantly, inhibited by anti-bFGF. The data demonstrate a paracrine interaction between myeloma and marrow stromal cells triggered by mutual stimulation of bFGF and IL-6.

Introduction

Microvessel density of the bone marrow is increased in patients with active multiple myeloma (MM). It parallels disease progression and correlates with poor prognosis.1-4 Myeloma cells express and secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)3,5,6 and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF),3,6,7 both of which are considered potent angiogenic cytokines8 and are likely to contribute to the increased angiogenic potential of bone marrow plasma cells in progressive MM.3

We and others have previously shown that VEGF derived from myeloma cells stimulates bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) to produce and secrete interleukin-6 (IL-6),5,9 an important growth and survival factor for human MM.10-12 Conversely, IL-6 enhances the production and secretion of VEGF by myeloma cells.5 Besides this paracrine circuit, VEGF may also directly mediate myeloma cell proliferation and migration.13 14

Basic FGF concentrations have also been shown to be increased in plasma cell lysates,3 bone marrow,15 and peripheral blood16 of patients with active MM. In the present study, we have therefore addressed the question of whether bFGF, other than its proangiogenic activity, also has a role in paracrine tumor–stromal cell interactions in MM.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and control subjects

Bone marrow samples from 18 patients with active MM were studied. For control experiments, marrow aspirates were obtained from 3 healthy volunteers and one lymphoma patient without marrow involvement. B lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy volunteers (n = 3). Patients and volunteers gave informed written consent prior to the sampling procedure. Approval was obtained from the institutional review board, Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty, University of Muenster. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Immunofluorescent labeling and cell sorting

Anti–CD38 phycoerythrin/cyanin-5 was purchased from Coulter-Immunotech (Hamburg, Germany). Anti-CD14 conjugated to phycoerythrin and anti–CD19 fluorescein isothiocyanate were obtained from Becton Dickinson (Heidelberg, Germany), and anti–CD138 fluorescein isothiocyanate was obtained from Serotec (Oxford, United Kingdom).

Murine monoclonal antibodies against human CD54, CD68, CD31, and thrombomodulin were purchased from DAKO (Glostrup, Denmark) and used for phenotypic characterization of BMSCs.

Bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) were separated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque at 1172g for 20 minutes (Amersham Pharmacia, Upsala, Sweden). CD38high/CD138+ plasma cells were isolated from the MNC fraction of patients with MM by fluorescence-activated cell sorting using a FacsVantage (Becton Dickinson). The remaining cells that were negative for the myeloma phenotype were defined as the nontumor cell fraction. CD19+/CD14− B lymphocytes were sorted from peripheral blood MNCs of healthy volunteers. On reanalysis, sorted populations had a purity of at least 95% (range, 95.0%-99.8%) for the defining phenotype.

Cell cultures

The human myeloma–derived cell lines RPMI-8226, U-266, and OPM-2 were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany). KMS-11 and KMS-18 were kindly provided by T. Otsuki, Kawasaki Medical School, Okayama, Japan. Cell lines, marrow MNCs, and sorted marrow myeloma cells from MM patients were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). Cultures of bone marrow stromal cells from MM patients (MM-BMSCs) or control subjects (control-BMSCs) were established from the MNC fraction of marrow aspirates according to the method of Lagneaux et al,17 with minor modifications. In brief, 5 × 105 cells/mL were cultured in minimal essential medium α (MEMα; Invitrogen, Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS in 75-cm2 flasks. The culture medium was replaced twice weekly until a confluent monolayer had developed (usually after 4-8 weeks). All culture media were supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). Cultures were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For stimulation experiments, BMSCs in passages 2 to 4 were grown in 24-well plates. Prior to stimulation, confluent layers were starved for 12 hours (1% FCS). During the stimulation period, BMSCs were kept in serum-free conditions.

Cocultures were established using a transwell system (pore size, 0.4 μm; Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) with myeloma cells seeded in the inserts at a density of 2 × 106/mL and confluent BMSCs growing on the bottom of the plates. The cocultures were maintained for 72 hours in serum-free conditions. This system precluded direct cell-cell contact between different cell types.

Stimulation of cell cultures

BMSCs were stimulated with different concentrations of recombinant human bFGF (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) for 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours in serum-free conditions. Inhibition experiments were performed using a neutralizing polyclonal goat antihuman anti-bFGF antibody (40 μg/mL; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). Thereafter, cells were pelleted and the supernatants were analyzed for IL-6. From BMSC pellets, total RNA was isolated for analysis of IL-6 transcripts. IL-6 concentrations in culture supernatants were determined by a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Quantikine, R&D Systems) with a lower detection limit of 0.7 pg/mL. Calibration curves were prepared by dilution of the IL-6 standard provided by the manufacturer in culture medium. Concentrations of IL-6 are presented as pg/mL corrected for 105 cells.

Myeloma cell lines and sorted marrow myeloma cells at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/mL were stimulated with recombinant human IL-6 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) at concentrations up to 10 ng/mL. For inhibition experiments, a monoclonal mouse antihuman IL-6 neutralizing antibody was used (1.5-5.0 μg/mL; R&D Systems). After 72 hours of stimulation, cells were harvested and centrifuged, and the supernatants were analyzed for bFGF. From pelleted cells, total RNA was isolated for analyses of bFGF transcripts. Basic FGF levels in culture supernatants were determined by a commercial ELISA (Quantikine, R&D Systems). The lower detection limit of the assay is 3 pg/mL. Calibration curves were prepared in culture medium by dilution of the bFGF standard provided by the manufacturer. Basic FGF concentrations in supernatants are presented as pg/mL corrected for 106cells.

Cocultures of MM-BMSCs and U-266 cells or highly purified CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells were performed either in the absence or presence of monoclonal mouse antihuman IL-6 antibody (1.5 μg/mL; R&D Systems), polyclonal goat antihuman bFGF antibody (40 μg/mL; R&D Systems), or anti-bFGF antibody plus monoclonal mouse antihuman VEGF antibody (10 μg/mL; R&D Systems). Supernatants were collected for determination of IL-6 and bFGF concentrations, and RNA for reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses was isolated from each cell population as described above. Unstimulated monocultures of myeloma cells or BMSCs served as controls for basal expression and secretion of IL-6 and bFGF, respectively.

Flow cytometric analyses

According to a frequently described procedure,18cells were collected after 72 hours of culture and stimulated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 1 ng/mL; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), ionomycin (1 μM; Sigma), and monensin (3 μM; Sigma), for 4 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2 for subsequent intracellular detection of bFGF. To prevent insufficient stimulation caused by cell sedimentation, samples were resuspended every 15 minutess. These initial steps were omitted for detection of FGF-receptor (FGF-R) subtypes. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells (4%; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco-BRL) including Ca2+ and Mg2+ were permeabilized by 0.1% saponin (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany). Intracellular labeling was performed using a polyclonal rabbit antihuman bFGF antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by staining with fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC)–coupled goat anti–rabbit immunoglobulin (Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany). Polyclonal rabbit antihuman antibodies for FGF-R expression studies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. FGF-R1, FGF-R3, and FGF-R4 antibodies are directed against N-terminal extracellular epitopes, while the FGF-R2 antibody recognizes the carboxyterminal terminus of FGF-R2. Therefore, cells had to be permeabilized by 0.1% saponin prior to FGF-R2 immunostaining. Cells were subsequently labeled with FITC-coupled goat anti–rabbit immunoglobulin. Rabbit anti–human immunoglobulin (DAKO) served as isotype control. Finally, flow cytometric analysis was performed using a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. Data represent 10 000 counted events per sample.

RNA preparation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was prepared using the guanidine isothiocyanate/phenol method19 (Trizol Reagent; Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Karlsruhe, Germany). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized for 1 hour at 37°C, using 1 μg total RNA, 40 U/μL RNA guard (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), 100 pmol/μL random hexamers (Amersham Pharmacia Invitrogen, NJ), 200 U M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), 5 × first strand buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, 375 mM KCl, 15 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 M dithiothreitol [DTT]), 80 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs; Amersham, NJ), and 1 μg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA, Serva).

RT-PCR analyses

Transcripts were amplified using Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) on a Hybrid thermocycler (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany) for 35 cycles as follows: at 94°C for 45 seconds, at 55°C for 45 seconds, and at 72°C for 45 seconds.

Basic FGF transcripts were amplified by RT-PCR using the following primer pair: 5′-GAG AAG AGC GAC CCT CAC A-3′ (sense) and 5′-TAG CTT TCT GCC CAG GTC C-3′ (antisense). Expression of the high-affinity FGF receptors R1 through R4 by myeloma cell lines was determined by RT-PCR using specific primer pairs for each receptor: FGF-R1, 5′-AAC CCC AGC CAC AAC CCA-3′ (sense), 5′-AAG CTG GGC TGG GTG TCG-3′ (antisense); FGF-R2, 5′-TCC TAT GAC ATT AAC CGT GTT-3′ (sense), 5′-TTT AAC ACT GCC GTT TAT GTG-3′ (antisense); FGF-R3, 5′-TTC GAC ACC TGC AAG CCG-3′ (sense), 5′-AGC AGG TCG TGG GCA AAC-3′ (antisense); FGF-R4, 5′-GCG GCG TCC ACC ACA TTG-3′ (sense), 5′-GTC TGC ACC CCA GAC CC-3′ (antisense). The t(4;14) transcripts were detected by nested RT-PCR technique using the following primers: 5′-AGC CCT TGT TAA TGG ACT TG-3′ (sense) and 5′-CCT CAA TTT CCC TGA AAT TGG TT-3′ (antisense) for the first round. Oligonucleotides containing the sequences 5′-CTT TGC AAG GCT CGC AGT GAC-3′ (sense) and 5′-AAG AAC TGT ACG TGA TAC TG-3′ (antisense) served as primers for the subsequent RT-PCR reaction.

In all PCR amplifications, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was coamplified as an internal control for RNA integrity, using 5′-GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT C-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC-3′ (antisense) as primers. GAPDH annealing temperature was modified to 53°C for 45 seconds.

A marker containing a 100–base pair (bp) DNA ladder (Fermentas, Hannover, MD) served as PCR product–length control.

All PCR-amplified products were separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and stained with ethidium bromide (Oncor, Gaithersburg, MD). For the estimation of semiquantitative gene expression, the corresponding signals were normalized against GAPDH, using a fluorometric analysis system (Gel Doc 1000; Bio-Rad Laboratories, München, Germany).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Quantitation of mRNA levels for bFGF and IL-6 was also carried out by means of the 5′ nuclease assay real-time fluorescence detection method.20-22 Briefly, cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR in the ABI prism 7700 sequence detector (PE Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Oligonucleotide probes annealed to the PCR products during the annealing and extension steps. The probes were labeled at the 5′ end with VIC (GAPDH) or FAM (bFGF and IL-6, respectively) and at the 3′ end with TAMRA, which served as a quencher. The 5′ to 3′ nuclease activity of the Taq polymerase cleaved the probe and released the fluorescent dyes (VIC or FAM), which were detected by the laser detector of the sequencer. After the detection threshold was reached, the fluorescence signal was proportional to the amount of PCR product generated. Primer and probe sequences were designed with Primer Express software (PE Biosystems) using published sequences. GAPDH primer pairs: 5′-GAA GGT GAA GGT CGG AGT C-3′ (sense), 5′-GAA GAT GGT GAT GGG ATT TC-3′ (antisense); GAPDH probe: VIC-5′-CAA GCT TCC CGT TCT CAG CC-3′-TAMRA; bFGF primer pairs: 5′-GAC GGC CGA GTT GAC GG-3′ (sense), 5′-TCT TCT GCT TGA AGT TGT AGC TTG A-3′ (antisense); bFGF probe: FAM-5′-TCC GGG AGA AGA GCG ACC CTC AC-3′-TAMRA; IL-6 primer pairs: 5′-CAG CCC TGA GAA AGG AGA CAT G-3′ (sense), 5′-GGT TCA GGT TGT TTT CTG CCA-3′ (antisense); IL-6 probe: FAM-5′-AAG AGT AAC ATG TGT GAA AGC AGC AAA GAG GC-3′-TAMRA.

The primer combinations produced a single product of the appropriate length as visualized by electrophoresis in a 6% polyaycrylamide gel. When genomic DNA was used as a template, no bands were seen after PCR amplification. All probes were positioned across exon-exon junctions. Gene expression levels were calculated by means of standard curves generated by serial dilutions of U-266 cDNA or BMSC cDNA. The relative amounts of gene expression were calculated by using the expression of GAPDH as an internal standard. GAPDH expression was stable during stimulation and coculture experiments. RT-PCR data are presented as means of at least 2 independent analyses.

Statistics

Data other than RT-PCR results are presented as individual data plots or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Statistical significance of overall differences between multiple groups was analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. If the test was significant, pairwise comparisons were done by the multiple-comparisons' criterion. Differences between 2 independent groups were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. The Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank test was used for comparison of differences within pairs.23 A P value of .05 or less was considered significant.

Results

Expression and secretion of bFGF by myeloma cells

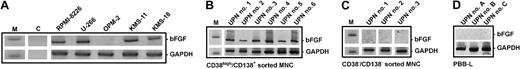

In accordance with earlier reports,3-5 bFGF mRNA transcripts were detected by RT-PCR in the myeloma-derived cell lines RPMI-8226, U-266, KMS-11, and KMS-18 (Figure1A), and in purified CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells from 12 of 15 MM patients studied (representative samples shown in Figure 1B). In contrast, OPM-2 cells (Figure 1A), nontumor (CD38−/CD138−) marrow MNCs from MM patients (Figure 1C), and peripheral blood B lymphocytes from healthy individuals (Figure 1D) did not express bFGF.

Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in myeloma cells.

Basic FGF transcripts (277 bp) in human myeloma cell lines (A) and in CD38high/CD138+ sorted myeloma cells from the bone marrow of representative patients (B; UPN nos. 1-6) were analyzed by RT-PCR. No bFGF transcripts were detected in the CD38−/CD138− nontumor cell fraction of corresponding marrow samples (C; UPN nos. 1-3). Peripheral blood B lymphocytes (PBB-Ls) obtained from healthy volunteers served as additional negative controls (D). DNA ladder marker (M) indicates 300 bp (upper rows) and 200 bp (lower rows). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 226 bp) was used as a control for RNA integrity. C indicates nontemplate PCR control.

Expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in myeloma cells.

Basic FGF transcripts (277 bp) in human myeloma cell lines (A) and in CD38high/CD138+ sorted myeloma cells from the bone marrow of representative patients (B; UPN nos. 1-6) were analyzed by RT-PCR. No bFGF transcripts were detected in the CD38−/CD138− nontumor cell fraction of corresponding marrow samples (C; UPN nos. 1-3). Peripheral blood B lymphocytes (PBB-Ls) obtained from healthy volunteers served as additional negative controls (D). DNA ladder marker (M) indicates 300 bp (upper rows) and 200 bp (lower rows). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; 226 bp) was used as a control for RNA integrity. C indicates nontemplate PCR control.

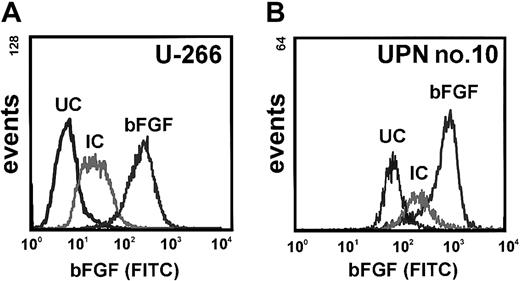

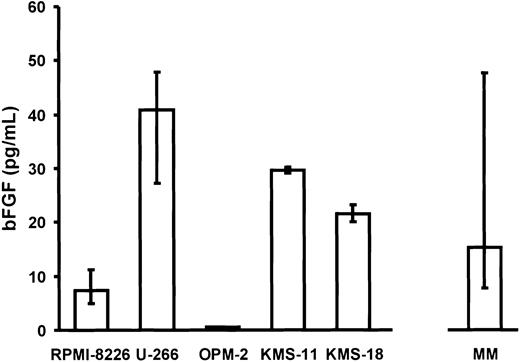

Consistent with these data, intracellular bFGF was detected by flow cytometric immunostaining in myeloma cell lines and MM patient cells (shown for U-266 and a representative patient; unique patient number [UPN] no. 10; Figure 2). Furthermore, RPMI-8226, U-266, KMS-11, KMS-18, and MM patient cells, but not OPM-2, were found to secrete bFGF into culture supernatants (Figure3). Basal secretion of bFGF protein was similar in the myeloma cell lines U-266, KMS-11, and KMS-18, and median concentrations in culture supernatants after 72 hours were 40.9 pg/mL (IQR, 27.3-47.8 pg/mL), 29.6 pg/mL (IQR, 29.1-30.1 pg/mL), and 21.6 pg/mL (IQR, 21.6-23.1 pg/mL) per 106 cells, respectively. By comparison, bFGF levels were lower in RPMI-8226 (median, 7.4 pg/mL; IQR, 4.9-11.3 pg/mL;P < .05, Mann-Whitney test) and undetectable in OPM-2.

Detection of intracellular basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in myeloma cells.

(A) Intracellular bFGF in U-266 myeloma cells stained by intracellular sandwich labeling using a polyclonal rabbit antihuman bFGF antibody and a goat antirabbit FITC-labeled secondary antibody. (B) Intracellular bFGF in sorted marrow myeloma cells from a representative patient (UPN no. 10). UC indicates unstained control; IC, isotype control.

Detection of intracellular basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in myeloma cells.

(A) Intracellular bFGF in U-266 myeloma cells stained by intracellular sandwich labeling using a polyclonal rabbit antihuman bFGF antibody and a goat antirabbit FITC-labeled secondary antibody. (B) Intracellular bFGF in sorted marrow myeloma cells from a representative patient (UPN no. 10). UC indicates unstained control; IC, isotype control.

Secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by myeloma cells.

Basal bFGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of myeloma cell lines (RPMI-8226, U-266, OPM-2, KMS-11, KMS-18; n = 8 independent experiments performed in triplicates per cell line) and of purified CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells from patients (MM, n = 18; see also Figure 4) after 72 hours of culture. Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106cells. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges.

Secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by myeloma cells.

Basal bFGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of myeloma cell lines (RPMI-8226, U-266, OPM-2, KMS-11, KMS-18; n = 8 independent experiments performed in triplicates per cell line) and of purified CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells from patients (MM, n = 18; see also Figure 4) after 72 hours of culture. Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106cells. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges.

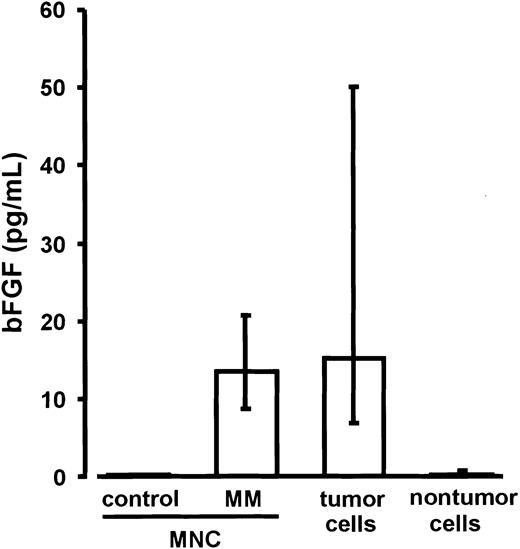

Basic FGF levels in the culture media of ficolled marrow MNCs from MM patients (n = 18; median, 13.5 pg/mL; IQR, 11.7-17.6 pg/mL) were similar to those measured ex vivo in the cell-free supernatants of untreated marrow aspirates (median, 27.7 pg/mL; IQR, 12.4-115.8 pg/mL) and significantly higher than in the media of marrow MNCs from control subjects (n = 4; median and IQR, 0.0 pg/mL; P < .02; Figure 4). For parallel experiments, MNCs of the MM marrows were sorted into CD38high/CD138+ myeloma and corresponding nontumor cell fractions. After 72 hours of culture, bFGF concentrations in the media of purified myeloma cells (median, 15.3 pg/mL; IQR, 7.7-47.7 pg/mL) were found to be significantly higher than in the media of nontumor cells (median, 0.4 pg/mL; IQR, 0.0-0.7 pg/mL;P < .0001; Figure 4). These results identified myeloma cells as the major source of bFGF in MM bone marrow.

Secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) as well as tumor and nontumor cells.

Basic FGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of marrow MNCs from control subjects (n = 4), marrow MNCs from patients with multiple myeloma (MM; n = 18), and of the corresponding sorted tumor and nontumor cell fractions of the MM marrows after 72 hours of culture. Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106cells. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between control MNCs and MM-MNCs (P = .02) and between tumor and nontumor cells (P < .0001).

Secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) as well as tumor and nontumor cells.

Basic FGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of marrow MNCs from control subjects (n = 4), marrow MNCs from patients with multiple myeloma (MM; n = 18), and of the corresponding sorted tumor and nontumor cell fractions of the MM marrows after 72 hours of culture. Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106cells. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between control MNCs and MM-MNCs (P = .02) and between tumor and nontumor cells (P < .0001).

FGF receptors in myeloma and marrow stromal cells

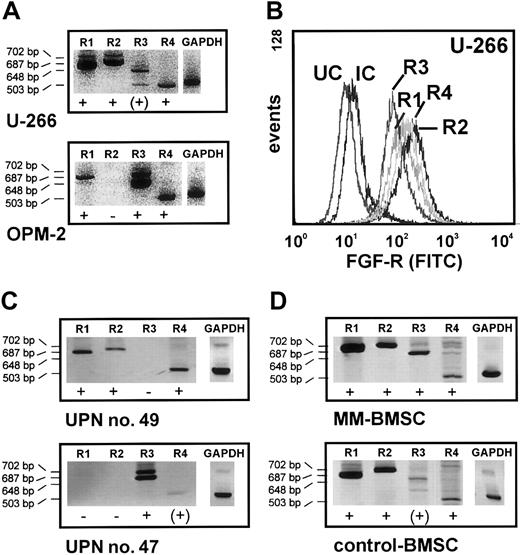

The expression of the high-affinity FGF receptors R1 through R4 was analyzed by flow cytometric phenotyping and RT-PCR in U-266, RPMI-8226, and OPM-2 cells. As shown for U-266 in Figure 5A-B, the cell lines mainly expressed the FGF receptor subtypes R1, R2, R4, and to a lesser extent R3. In contrast, RT-PCR indicated overexpression of FGF-R3 in OPM-2 cells (Figure 5A). OPM-2 cells are known to carry the translocation t(4;14), and this finding was confirmed by specific RT-PCR (not shown).24 FGF-R1 through FGF-R4 expression was also examined on cultured myeloma cells derived from 6 MM patients. As shown for a representative patient in Figure 5C (UPN no. 49), patient myeloma cells consistently expressed mainly R1, R2, and R4. However, in line with the findings on OPM-2, myeloma cells from one patient with t(4;14) as detected by RT-PCR showed dominant overexpression of FGF-R3 (Figure5C, UPN no. 47).

Expression of FGF receptors 1 through 4 (FGF-R1-4) in myeloma and stromal cells.

(A) FGF-R1-4 expression in 2 myeloma cell lines (U-266, OPM-2) using RT-PCR. Note the FGF-R3 overexpression in OPM-2 cells. (B) Flow cytometric detection of FGF-R1-4 in U-266 myeloma cells stained by sandwich labeling using polyclonal rabbit antihuman antibodies directed against FGF-R1-4 and a goat antirabbit FITC-labeled secondary antibody. UC indicates unstained control; IC, isotype control. (C) FGF-R1-4 transcripts in purified marrow myeloma cells of representative patients. Note the FGF-R3 overexpression in the t(4;14)-positive MM patient (UPN no. 47). (D) Amplified FGF-R1-4 transcripts in marrow stromal cells from a representative myeloma patient (MM-BMSCs) and a control subject (control-BMSCs). The product size for each receptor isotype is indicated on the left. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control for RNA integrity. + indicates transcript detectable by RT-PCR; −, no transcript detectable by RT-PCR.

Expression of FGF receptors 1 through 4 (FGF-R1-4) in myeloma and stromal cells.

(A) FGF-R1-4 expression in 2 myeloma cell lines (U-266, OPM-2) using RT-PCR. Note the FGF-R3 overexpression in OPM-2 cells. (B) Flow cytometric detection of FGF-R1-4 in U-266 myeloma cells stained by sandwich labeling using polyclonal rabbit antihuman antibodies directed against FGF-R1-4 and a goat antirabbit FITC-labeled secondary antibody. UC indicates unstained control; IC, isotype control. (C) FGF-R1-4 transcripts in purified marrow myeloma cells of representative patients. Note the FGF-R3 overexpression in the t(4;14)-positive MM patient (UPN no. 47). (D) Amplified FGF-R1-4 transcripts in marrow stromal cells from a representative myeloma patient (MM-BMSCs) and a control subject (control-BMSCs). The product size for each receptor isotype is indicated on the left. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a control for RNA integrity. + indicates transcript detectable by RT-PCR; −, no transcript detectable by RT-PCR.

BMSCs derived from both MM patients and control subjects expressed FGF-R1 through FGF-R4 (representative results in Figure5D).

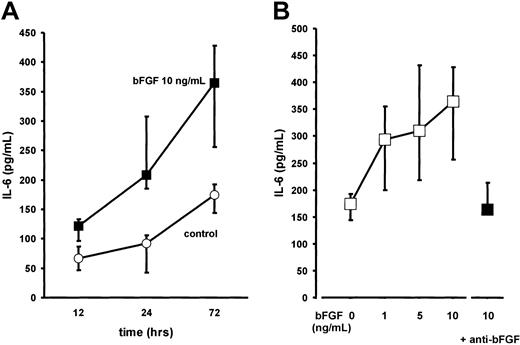

Basic FGF stimulates IL-6 expression and secretion in MM-BMSCs and control-BMSCs

BMSC cultures were established from bone marrow aspirates of 13 patients with multiple myeloma (MM-BMSCs) as previously described.5 Stimulation of BMSCs with bFGF for up to 72 hours induced a time- and dose-dependent increase in IL-6 secretion (2-fold over unstimulated controls at 10 ng/mL of bFGF after 72 hours;P < .001; Figure 6). The increase in IL-6 secretion was completely abrogated in the presence of an antihuman bFGF antibody (working concentration, 40 μg/mL; Figure6B). Stimulation of BMSC cultures from control subjects with bFGF revealed a similar time- and dose-dependent increase in IL-6 levels as observed for MM-BMSCs (not shown).

Effect of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion by bone marrow stromal cells from myeloma patients (MM-BMSCs).

(A) Time-course experiments: IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free culture supernatants of MM-BMSCs exposed to (▪) 10 ng/mL of bFGF for 12, 24, and 72 hours; (○), unstimulated controls. IL-6 concentrations were corrected for 105 cells. Data represent median values and interquartile ranges of 7 independent experiments in different MM-BMSC cultures. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the multiple comparisons' criterion were used to identify differences between groups (10 ng/mL vs controls, P = .05 at 12 hours;P = .001 at 24 hours; P = .0001 at 72 hours). (B) Dose-response effects: IL-6 concentrations were determined in 13 independent MM-BMSC cultures stimulated with 1, 5, or 10 ng/mL of bFGF for 72 hours (■). As a control experiment, stimulation with 10 ng/mL of bFGF was also performed in the presence of polyclonal antihuman bFGF neutralizing antibody (anti-bFGF, 40 μg/mL) in serum-free conditions (▪). IL-6 concentrations are corrected for 105 cells. Data represent median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between groups (10 ng/mL bFGF vs controls, P < .001; 10 ng/mL bFGF vs 10 ng/mL bFGF + anti-bFGF, P = .01).

Effect of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on interleukin-6 (IL-6) secretion by bone marrow stromal cells from myeloma patients (MM-BMSCs).

(A) Time-course experiments: IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free culture supernatants of MM-BMSCs exposed to (▪) 10 ng/mL of bFGF for 12, 24, and 72 hours; (○), unstimulated controls. IL-6 concentrations were corrected for 105 cells. Data represent median values and interquartile ranges of 7 independent experiments in different MM-BMSC cultures. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the multiple comparisons' criterion were used to identify differences between groups (10 ng/mL vs controls, P = .05 at 12 hours;P = .001 at 24 hours; P = .0001 at 72 hours). (B) Dose-response effects: IL-6 concentrations were determined in 13 independent MM-BMSC cultures stimulated with 1, 5, or 10 ng/mL of bFGF for 72 hours (■). As a control experiment, stimulation with 10 ng/mL of bFGF was also performed in the presence of polyclonal antihuman bFGF neutralizing antibody (anti-bFGF, 40 μg/mL) in serum-free conditions (▪). IL-6 concentrations are corrected for 105 cells. Data represent median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs). The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between groups (10 ng/mL bFGF vs controls, P < .001; 10 ng/mL bFGF vs 10 ng/mL bFGF + anti-bFGF, P = .01).

Quantitative RT-PCR showed a 3- to 10-fold increase in IL-6 transcripts in MM-BMSCs after exposure to 10 ng/mL bFGF for 72 hours, indicating that bFGF-induced stimulation of IL-6 production occurred at the mRNA level (data not shown; compare quantitative RT-PCR data in coculture experiments shown in Figure 9A, insert).

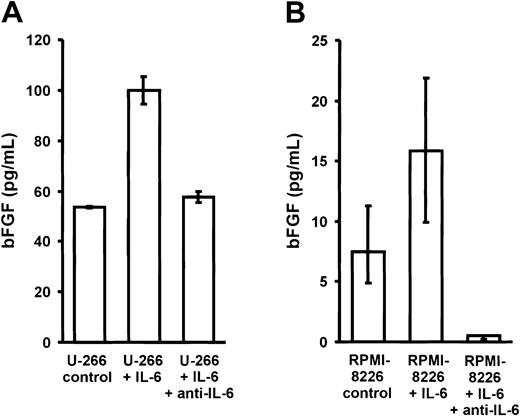

Effects of IL-6 on bFGF expression and secretion in myeloma cells

To analyze whether IL-6 would in turn stimulate the secretion of bFGF by myeloma cells, U-266 and RPMI-8226 myeloma cell lines were cultured for 72 hours in the absence or presence of exogenous IL-6 (10 ng/mL) with or without antihuman IL-6 antibody (1.5 μg/mL) (Figure7). A 2-fold increase in bFGF concentrations was observed in culture supernatants of both cell lines, which was completely inhibited in the presence of an IL-6–neutralizing antibody.

Effect of interleukin-6 (IL-6) on basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) secretion by myeloma cell lines.

Basic FGF concentrations in supernatants of U-266 (A) and RPMI-8226 (B) cells after exposure to 0 (control) or 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 72 hours in the absence or presence of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (1.5 μg/mL anti–IL-6). Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 3 independent experiments. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between groups (U-266: control vs IL-6,P = .02; IL-6 vs anti–IL-6, P = .02; RPMI-8226: control vs IL-6, P = .1; IL-6 vs anti–IL-6,P = .02).

Effect of interleukin-6 (IL-6) on basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) secretion by myeloma cell lines.

Basic FGF concentrations in supernatants of U-266 (A) and RPMI-8226 (B) cells after exposure to 0 (control) or 10 ng/mL IL-6 for 72 hours in the absence or presence of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (1.5 μg/mL anti–IL-6). Basic FGF concentrations were corrected for 106 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 3 independent experiments. The Mann-Whitney rank sum test was used to identify differences between groups (U-266: control vs IL-6,P = .02; IL-6 vs anti–IL-6, P = .02; RPMI-8226: control vs IL-6, P = .1; IL-6 vs anti–IL-6,P = .02).

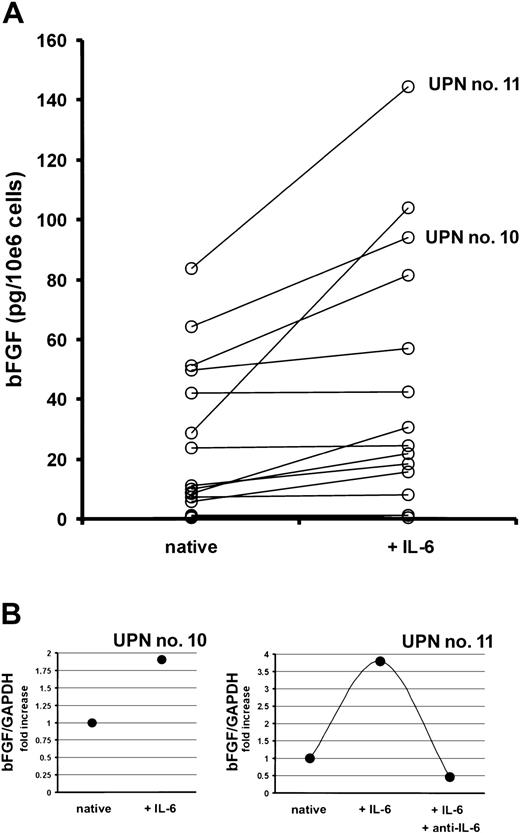

Next, myeloma cells sorted from bone marrow aspirates of 18 MM patients were cultured in the presence or absence of IL-6 (10 ng/mL) for 72 hours. Although highly variable, IL-6 stimulated the bFGF secretion into culture supernatants up to 3.6-fold (median, 1.5-fold,P < .002; Figure 8A). In line with these results, an increase in bFGF mRNA levels was observed in IL-6–stimulated marrow myeloma cells using quantitative RT-PCR (Figure 8B). As shown for a representative patient, this effect of IL-6 could again be completely inhibited by the IL-6–neutralizing antibody.

Effect of interleukin-6 (IL-6) on the production of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by purified marrow myeloma cells from patients (n = 18).

(A) Basic FGF concentrations in supernatants of myeloma cell cultures after exposure to 0 (native) or 10 ng/mL of IL-6 for 72 hours, presented as pg/mL corrected for 106 cells.P < .002 for difference between native and IL-6–stimulated myeloma cells (Wilcoxon test). (B) Quantitative bFGF-RT-PCR in CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells of 2 patients (UPN nos. 10 and 11) after exposure to 0 (native) or 10 ng/mL of IL-6 with or without anti–IL-6 for 72 hours. Basic FGF-RT-PCR was performed as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Ratios of bFGF over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are depicted as fold increase over unstimulated controls. Corresponding patient numbers (UPN) are indicated in panels A and B.

Effect of interleukin-6 (IL-6) on the production of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) by purified marrow myeloma cells from patients (n = 18).

(A) Basic FGF concentrations in supernatants of myeloma cell cultures after exposure to 0 (native) or 10 ng/mL of IL-6 for 72 hours, presented as pg/mL corrected for 106 cells.P < .002 for difference between native and IL-6–stimulated myeloma cells (Wilcoxon test). (B) Quantitative bFGF-RT-PCR in CD38high/CD138+ marrow myeloma cells of 2 patients (UPN nos. 10 and 11) after exposure to 0 (native) or 10 ng/mL of IL-6 with or without anti–IL-6 for 72 hours. Basic FGF-RT-PCR was performed as described in “Patients, materials, and methods.” Ratios of bFGF over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are depicted as fold increase over unstimulated controls. Corresponding patient numbers (UPN) are indicated in panels A and B.

Up-regulation of IL-6 and bFGF in transwell cocultures of myeloma and marrow stromal cells

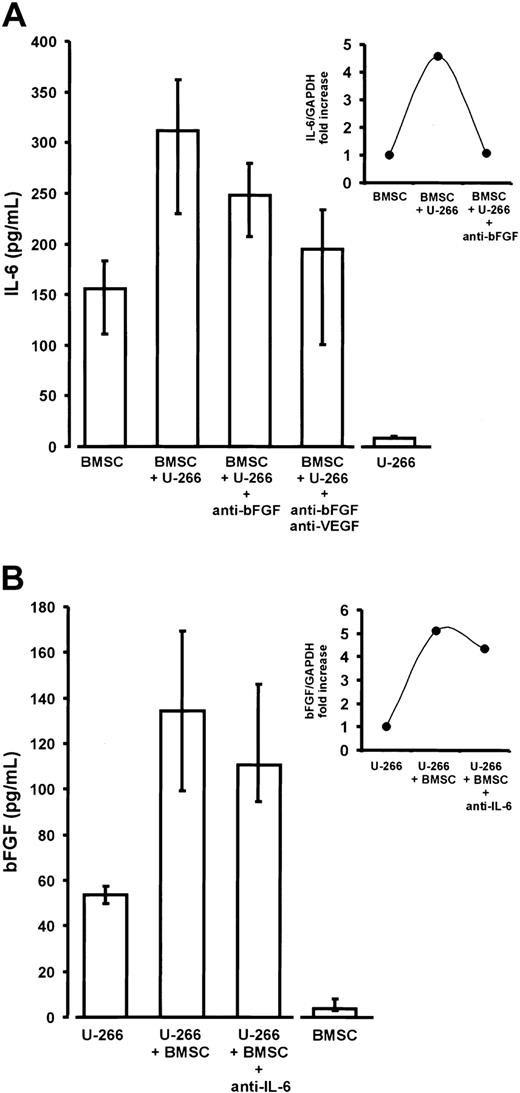

To further support the hypothesis of an enhancing interaction between bFGF and IL-6 within the marrow of myeloma patients, we studied the mutual effects of cocultivation of myeloma and marrow stromal cells on IL-6 and bFGF secretion. In order to preclude direct myeloma-to–stromal cell contacts, we chose a transwell coculture system. In this series of experiments, BMSCs from MM patients were cocultured with either U-266 cells (Figure9) or CD38high/CD138+ myeloma cells purified from the marrow of MM patients (Figure 10). Monocultures were used as controls in order to determine basal IL-6 and bFGF secretion by either cell type alone.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in noncontact cocultures of U-266 myeloma cells and bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs).

(A) Enhanced IL-6 secretion of BMSCs derived from myeloma patients in transwell cocultures with U-266 cells (P < .01 vs BMSC monocultures). The addition of anti-bFGF or anti-bFGF plus anti-VEGF antibodies resulted in a significant reduction of IL-6 secretion (P = .01 and P = .02, respectively, versus native cocultures containing no antibody). IL-6 secretion by BMSCs and U-266 monocultures served as baseline controls. IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free supernatants of 72-hour cultures. Results were corrected for 105 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 9 independent coculture experiments with BMSCs from different patients. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. The insert shows the induction of IL-6 transcripts in BMSCs by noncontact cocultivation with U-266 cells and its reversal by the addition of anti-bFGF antibody (quantitative IL-6 RT-PCR in a representative coculture). Ratios of IL-6 over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are depicted as fold increase over the unstimulated control. (B) Increased bFGF secretion into supernatants of transwell cocultures of U-266 cells with BMSCs for 72 hours (P = .03 vs U-266 monocultures). The addition of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (5 μg/mL) slightly, but not significantly, decreased bFGF secretion. U-266 and BMSC monocultures served as baseline controls. BFGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of serum-free 72-hour cultures. Results were corrected for 106 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 3 independent experiments. The insert shows the induction of bFGF transcripts in U-266 myeloma cells by noncontact coincubation with BMSCs and the effect of anti–IL-6 antibody (quantitative bFGF RT-PCR, representative experiment). Ratios of bFGF over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are shown as fold increase over the unstimulated control.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in noncontact cocultures of U-266 myeloma cells and bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs).

(A) Enhanced IL-6 secretion of BMSCs derived from myeloma patients in transwell cocultures with U-266 cells (P < .01 vs BMSC monocultures). The addition of anti-bFGF or anti-bFGF plus anti-VEGF antibodies resulted in a significant reduction of IL-6 secretion (P = .01 and P = .02, respectively, versus native cocultures containing no antibody). IL-6 secretion by BMSCs and U-266 monocultures served as baseline controls. IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free supernatants of 72-hour cultures. Results were corrected for 105 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 9 independent coculture experiments with BMSCs from different patients. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. The insert shows the induction of IL-6 transcripts in BMSCs by noncontact cocultivation with U-266 cells and its reversal by the addition of anti-bFGF antibody (quantitative IL-6 RT-PCR in a representative coculture). Ratios of IL-6 over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are depicted as fold increase over the unstimulated control. (B) Increased bFGF secretion into supernatants of transwell cocultures of U-266 cells with BMSCs for 72 hours (P = .03 vs U-266 monocultures). The addition of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (5 μg/mL) slightly, but not significantly, decreased bFGF secretion. U-266 and BMSC monocultures served as baseline controls. BFGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of serum-free 72-hour cultures. Results were corrected for 106 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 3 independent experiments. The insert shows the induction of bFGF transcripts in U-266 myeloma cells by noncontact coincubation with BMSCs and the effect of anti–IL-6 antibody (quantitative bFGF RT-PCR, representative experiment). Ratios of bFGF over glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression are shown as fold increase over the unstimulated control.

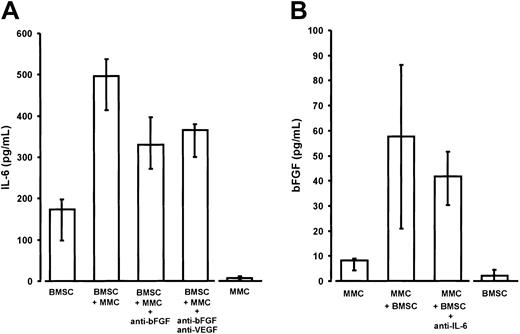

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in noncontact cocultures of purified marrow myeloma cells (MMCs) and stromal cells (BMSCs) from patients.

(A) Enhanced IL-6 secretion of BMSCs derived from myeloma patients in transwell cocultures with MMCs (P = .02 vs BMSC monocultures). The addition of anti-bFGF or anti-bFGF plus anti-VEGF antibody resulted in a significant reduction of IL-6 secretion (P = .02 and P = .02, respectively, vs native cocultures containing no antibody). IL-6 secretion by BMSCs and MMCs served as baseline controls. IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free supernatants of 72-hour culture. Results were corrected for 105 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 5 independent experiments. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Increased bFGF secretion into supernatants of noncontact cocultures of MMCs with BMSCs (P = .03 vs MMC monocultures). The addition of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (5 μg/mL) revealed no significant effect. Basic FGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of serum-free 72-hour cultures and corrected for 106 cells. MMC and BMSC monocultures served as baseline controls. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 4 independent experiments. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) in noncontact cocultures of purified marrow myeloma cells (MMCs) and stromal cells (BMSCs) from patients.

(A) Enhanced IL-6 secretion of BMSCs derived from myeloma patients in transwell cocultures with MMCs (P = .02 vs BMSC monocultures). The addition of anti-bFGF or anti-bFGF plus anti-VEGF antibody resulted in a significant reduction of IL-6 secretion (P = .02 and P = .02, respectively, vs native cocultures containing no antibody). IL-6 secretion by BMSCs and MMCs served as baseline controls. IL-6 concentrations were determined in serum-free supernatants of 72-hour culture. Results were corrected for 105 cells and are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 5 independent experiments. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. (B) Increased bFGF secretion into supernatants of noncontact cocultures of MMCs with BMSCs (P = .03 vs MMC monocultures). The addition of polyclonal antihuman IL-6 antibody (5 μg/mL) revealed no significant effect. Basic FGF concentrations were determined in supernatants of serum-free 72-hour cultures and corrected for 106 cells. MMC and BMSC monocultures served as baseline controls. Data are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 4 independent experiments. Analysis of significance for group differences was performed by the Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

Cocultivation of BMSCs with either U-266 or patient MM cells resulted in a significant 2- to 3-fold stimulation of IL-6 secretion over the sum of basal concentrations in the monoculture controls (Figures 9A and10A). The presence of both anti-bFGF antibody and the combination of anti-bFGF with anti-VEGF significantly reduced the enhancing effect of cocultivation, indicating a role for bFGF as a mediator of IL-6 stimulation. This was true for U-266 as well as patient MM cells. Finally, quantitative RT-PCR of IL-6 transcripts in monocultures or cocultures of BMSCs, in the absence or presence of anti-bFGF antibody, demonstrates a regulatory effect of bFGF on IL-6 production by marrow stromal cells (Figure 9A, insert). However, the inhibitory effect of anti-bFGF even in combination with anti-VEGF was incomplete, suggesting that additional humoral mediators are involved in stimulating BMSCs.

In turn, there was a supra-additive increase of bFGF in coculture supernatants (Figures 9B and 10B). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses in U-266 cells revealed that increased bFGF production by myeloma cells was likely to account for at least part of the bFGF increase (Figure9B, insert). However, in contrast to monoculture experiments, we were unable to demonstrate a significant inhibition of bFGF secretion in cocultures by IL-6–neutralizing antibodies.

Discussion

Bone marrow neovascularization is increased in MM and characterizes active disease with poor clinical outcome.1-3,25 These recent observations have implicated a role in myeloma progression for angiogenic cytokines such as VEGF and bFGF, both of which are expressed by myeloma cells.3,5,6,26,27 Besides its angiogenic activity, VEGF has also been shown to stimulate myeloma cell proliferation and migration in an autocrine manner and to support the growth of and confer apoptosis resistance to myeloma cells through paracrine induction of IL-6 release from marrow stromal cells.5,9,13,28 Basic FGF, too, is considered a potent angiogenic cytokine in MM.3 However, in contrast to VEGF, little is known about potential autocrine and paracrine pathways triggered by bFGF. Therefore, the present study aimed at investigating the contribution of bFGF to paracrine IL-6 secretion from stromal cells in the marrow microenvironment.

Our findings corroborate previous reports demonstrating that various myeloma-derived cell lines, except OPM-2, as well as purified marrow myeloma cells from patients express and secrete bFGF.3,6,26,27 The present data extend these observations in that they identify myeloma cells as the prevailing source of bFGF in the bone marrow of patients with active MM (Figure 4). The latter results would explain why bFGF concentrations in marrow aspirates and peripheral blood have been found to correlate with MM disease activity.15,16 29

Signaling of bFGF is mediated by a familiy of tyrosine kinase receptors comprising FGF-R1 through FGF-R4 and the recently described FGF-R5.30-35 These receptors transduce signals related to cell growth, differentiation, tissue modeling, and angiogenesis.36-38 Binding of bFGF to one of its receptors requires the interaction with heparan sulfate proteoglycans such as syndecan-1, which is present on the surface of myeloma cells and in their stromal environment.39-42 In the cell lines RPMI-8226 and U-266, and in purified myeloma cells from patients, we could demonstrate expression of the high-affinity FGF receptors R1 through R4. Although not addressed in the present study, the simultaneous expression of bFGF and its high-affinity receptors by myeloma cells gives rise to the speculation on an autocrine loop as it was recently described for VEGF.13 As an exception, predominant expression of FGF-R3 was evident in those patient cells and myeloma cell lines (OPM-2, KMS-11, KMS-18) carrying the translocation t(4;14), which is known to result in dysregulated expression of the receptor gene.7 43 FGF-R5 expression by myeloma and stromal cells was not studied in the present series and thus cannot be excluded.

In line with earlier reports on marrow stromal cells in humans,44 we also showed expression of FGF-R1 through FGF-R4 in BMSCs from control subjects and MM patients, indicating that paracrine bFGF signaling in the marrow microenvironment may occur. As previously described, the BMSC cultures used in our experiments mainly consisted of CD54+ fibroblastlike cells with few CD68+ macrophages, but without CD31 or thrombomodulin-reactive endothelial cells.5 45 Thus, the observations on bFGF-induced IL-6 release from BMSCs indicate that paracrine bFGF effects do not depend on the presence of microvascular endothelium in the vicinity of the tumor.

Similar to the previously described effects of VEGF121 and VEGF165,5 our results demonstrate that bFGF induces a time- and dose-dependent increase in IL-6 secretion by BMSCs. These findings suggest that bFGF is not only an angiogenic growth factor in MM, but also functions as a cytokine supporting myeloma cell growth and survival by paracrine stimulation of IL-6 release from the marrow stroma.

The IL-6 release induced by bFGF appears to be less pronounced than that reported for VEGF.5 In addition, although bFGF effects were observed with concentrations as low as 1 ng/mL, these concentrations are still one order of magnitude higher than those measured in culture supernatants of myeloma cells. Nonetheless, it is conceivable that concentrations of myeloma-derived bFGF sufficient to elicit an IL-6 response may be reached in the vicinity of a myeloma cell infiltrate in the marrow.

Other than bFGF and VEGF, myeloma cells have been shown to secrete cytokines including transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-1β, which are capable of stimulating IL-6 secretion by marrow stromal cells.46-49 In order to rule out an effect of such cytokines, bFGF stimulations of cultured BMSCs were performed under serum-free conditions. Apart from these humoral mediators, adhesion of myeloma cells to bone marrow stroma has also been shown to potently stimulate IL-6 secretion.9 50-53

These data and observations led us to examine the role of bFGF in a transwell coculture model, which precluded direct cell-to-cell contact between the myeloma and stromal cell compartments. The observation of a supra-additive effect of cocultivation on IL-6 release and its significant, though partial, inhibition by anti-bFGF antibodies strongly supports the hypothesis of a paracrine effect of bFGF on IL-6 secretion. The increase in IL-6 transcripts in BMSCs upon cocultivation with myeloma cells and its reversal by anti-bFGF antibodies further confirms this conclusion. Finally, consistent findings in cocultures of BMSCs not only with the cell line U-266, but also with patient cells, underline the biologic relevance of the bFGF effect in human MM.

In analogy to the data reported on VEGF,5 we were also able to demonstrate reciprocal stimulation of bFGF transcription and secretion in myeloma cells by IL-6. This effect and its specific inhibition by anti–IL-6 antibodies was observed in cell lines (ie, U-266 and RPMI-8226) and in purified marrow myeloma cells from some, but not all, MM patients. In line with the findings in IL-6–stimulated myeloma cell monocultures, the transwell coculture experiments revealed a significant supra-additive increase in bFGF release when myeloma cells were cultured in the presence of BMSCs. However, in cocultures the bFGF release was not significantly inhibited by anti–IL-6 antibodies, indicating that bFGF secretion is redundantly regulated.

Finally, the question arises whether the bFGF release into coculture supernatants is entirely derived from myeloma cells. As mentioned above, cell-sorting studies revealed myeloma cells to be the primary source of bFGF in the marrow of patients with active MM. In addition, we detected only trace amounts of bFGF in supernatants of BMSC monocultures (compare Figures 4, 9, and 10). Therefore, we tend to attribute the increase of bFGF in cocultures and the related effects on IL-6 to enhanced bFGF secretion by myeloma cells. Support of this interpretation comes from a preliminary report by Van Riet et al,26 demonstrating that BMSC-conditioned media induced a 5-fold increase in bFGF production by the myeloma cell lines MMs.1 and U-266, while cocultivation with MM cell lines had no effect on the stromal production of bFGF. Nonetheless, there is some controversy as to the relative contributions of BMSCs and myeloma cells to bFGF secretion. Gupta et al9 showed that cultured BMSCs are equally and sometimes more potent than myeloma cells in releasing bFGF. In their study, binding of myeloma cells to BMSCs decreased, rather than increased, bFGF concentrations in culture supernatants.9 Considering that we used transwell cocultures precluding adherence of myeloma cells to BMSCs, our findings in cocultures are not necessarily conflicting with this report because they merely reflect the effect of humoral mediators on bFGF release. However, our experiments cannot exclude an additional induction of bFGF secretion from BMSCs by yet unidentified myeloma-derived mediators. After all, this possibility would not detract from the observation that bFGF, be it derived from myeloma or stromal cells, is a biologically relevant paracrine mediator of IL-6 secretion by marrow stromal cells.

Taken together, the mutual stimulation of bFGF and IL-6 strongly suggests a role for bFGF in paracrine interactions between myeloma and marrow stromal cells, similar to the role previously described for VEGF.5 These findings are particularly relevant in view of new treatment strategies for MM targeting marrow neovascularization or angiogenic cytokines and their receptors.54-56

D.W. contributed experiments to fulfill requirements for her MD thesis.

We thank Takemi Otsuki from Kawasaki Medical School, Okayama, Japan, for kindly providing the KMS-11 and KMS-18 myeloma cell lines.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, November 27, 2002; DOI 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2907.

G.B. and R.L. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

Author notes

J. Kienast, Department of Medicine/Hematology and Oncology, University of Muenster, Albert-Schweitzer-Str 33, D-48129 Muenster, Germany; e-mail:kienast@uni-muenster.de.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal