Abstract

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) and T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) are distinct tumors and are treated differently. They are linked by a morphologic and probably a biologic continuum, which renders the differential diagnosis difficult. To develop criteria to distinguish the entities along the morphologic continuum, we correlated the lymph node architecture and immunophenotype of both tumor cells and reactive components of 235 neoplasms in the spectrum of NLPHL and T/HRBCL with clinical data. Two hundred and eighteen cases fitted the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria of NLPHL (139) or T/HRBCL (79). While tumor cells in both entities were immunophenotypically similar, background composition differed: in NLPHL small B cells and CD3+CD4+CD57+ T cells were common, whereas in T/HRBCL, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and histiocytes dominated. Follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) formed expanded meshworks in NLPHL, whereas they were absent in T/HRBCL. Seventeen cases represented a gray zone: within FDC meshworks, neoplastic B cells resided in a background depleted of small B cells but rich in T cells and histiocytes. Tumor cells either were loosely scattered or formed clusters, thus resembling areas of either T/HRBCL or inflammatory diffuse large BCL (DLBCL) within the nodules. Patients with these NLPHLs with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules presented at a high stage and with B symptoms, as in T/HRBCL, but had an excellent survival, as in NLPHL. This morphologic pattern suggests a biologic continuum between NLPHL and T/HRBCL. (Blood. 2003;102:3753-3758)

Introduction

Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) accounts for 6.5% of cases in the German Hodgkin lymphoma study. It is characterized by a nodular, or a nodular and diffuse proliferation of scattered large neoplastic cells (lymphocytic and/or histiocytic [L&H] cells or “popcorn” cells) in large spherical meshworks of follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) filled with nonneoplastic small lymphocytes, mainly of B-cell type.1 There have been doubts whether a purely diffuse lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (LPHL) really exists.2,3

NLPHL has recently been distinguished from the nodular lymphocyte-rich variant of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), based on immunophenotype. In contrast to cHL, tumor cells of NLPHL do not express CD30 and CD15, but they are positive for B-cell markers (CD20, CD79a), immunoglobulins, J chain, and epithelial membrane antigen.1 The B-cell phenotype and genetic features of NLPHL, exhibiting clonally rearranged immunoglobulin genes with ongoing mutations,4,5 indicate its close relationship to B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas.2,6

Among B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, T-cell/histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma (T/HRBCL) represents a variant of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in which neoplastic CD20+ B cells, accounting for less than 10% of the infiltrate, are scattered among the majority of nonneoplastic T cells with or without histiocytes.2 Nevertheless, T/HRBCL seems heterogeneous, comprising several subgroups. The tumor cells may resemble centroblasts, immunoblasts, Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells, or L&H cells.2,7-11

The clinical presentation and treatment strategies of NLPHL and T/HRBCL are different.12,13 NLPHL presents at a localized clinical stage and pursues an indolent course,2 while T/HRBCL presents typically at a high stage and its outcome is worse.7,9,13-17 According to morphologic, immunophenotypic, molecular-genetic, and clinical data gathered over several past years, there exists a substantial overlap—a gray zone—between NLPHL and T/HRBCL.2,6,13,18 Both diseases may occur as composite lymphomas in the same lymph node or in subsequent biopsies, as well as in members of the same family.13,19 In addition, a diffuse pattern in NLPHL may represent a morphologic tumor progression and transition to T/HRBCL. The tumor cells of NLPHL and T/HRBCL are alike not only morphologically, but also immunophenotypically.20 Only PU.1, a transcription factor essential for B-cell development, has been described as being expressed more often in NLPHL than in T/HRBCL, albeit in a small number of cases.21 However, differences in the background composition and growth pattern do exist.2,13,20,22 To choose treatment and to include patients in clinical studies, it is essential to distinguish NLPHL from T/HRBCL.

The differential diagnosis is not settled for cases sharing architectural and immunomorphologic features of both NLPHL and T/HRBCL. We compared pathologic and clinical properties of a large series of cases from the gray zone, as well as of unequivocally diagnosed typical NLPHL and T/HRBCL, to define criteria to distinguish these entities. After a thorough analysis, 17 cases still could not be readily diagnosed as NLPHL or T/HRBCL, and we determined their pathologic and clinical characteristics.

Materials and methods

Case selection and immunophenotypic studies

From the files of the Institute of Pathology in Würzburg, Germany, we retrieved all 235 primary diagnostic lymph node biopsies diagnosed as either T/HRBCL or NLPHL between 1996 and 2001 and reviewed them with immunostains for CD20, CD30, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD21, and CD3. If necessary, additional stains were performed. Among the biopsies, we identified 64 lymph node specimens with peculiar features: NLPHL displaying abundant tumor cells or a predominantly diffuse growth pattern and T/HRBCL showing some degree of nodularity. These 64 specimens were compared in detail with 41 randomly selected typical control cases of NLPHL (25) and T/HRBCL (16). All together, 105 tumors were stained with an extended immunohistochemistry panel on an automated immunostainer (Tecan, Crailsheim, Germany), while 130 cases (86 typical NLPHL and 44 typical T/HRBCL) were not investigated further. In tumor cells, we assessed the reactivity for CD20, CD79a, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CD30, bcl-2 (all obtained from Dako, Hamburg, Germany), transcription factor PU.1 (clone G148-74; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and Ki-67 antigen (Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom); interferon consensus sequence binding protein for activated T cells (ICSATs) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), J chain (Biogenex, San Ramon, CA). Results were scored positive if more than occasional tumor cells (more than 30%) were positive.

In the reactive background, T-cell subsets were evaluated with the use of CD3, CD4 (Novocastra), CD8 (Dako), CD57, T-cell intracellular antigen 1 (TIA-1) (Immunotech, Marseilles, France), and granzyme B (Monosan, Uden, the Netherlands). To achieve higher reproducibility of the data, in CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD57 stains, the rosettes around the neoplastic cells were evaluated; these were well correlated with the overall number of cells. Macrophages were studied with the use of the antibodies KiM1P (a kind gift from Prof Dr R. M. Parwaresch, Kiel, Germany) and PU.1. All these were graded semiquantitatively on an interval scale (none < occasional < moderate < many). For comparison, cases with more than occasional stained background cells/rosettes were considered. The presence and density of FDC meshworks were evaluated by means of anti-CD21 staining (Dako).

In 47 selected cases (33 T/HRBCLs, 2 NLPHLs, the 2 diffuse LPHLs, and 10 cases not meeting the criteria for either NLPHL or T/HRBCL), numbers of both small nonneoplastic and large neoplastic B cells were counted separately in CD20 stains in 5 high-power fields (HPFs) with a 40 × objective, by means of an eyepiece grid in an Olympus BX 50 microscope (Olympus, Japan) and a manual cell counter.

Diagnostic criteria

The diagnoses were established in consensus by L.B., T.R., and H.-K.M.-H. without knowledge of the clinical features. World Health Organization (WHO) criteria2 were applied to assign cases to NLPHL or T/HRBCL. Briefly, in NLPHL, tumor cells were scattered within preserved FDC meshworks filled with numerous small B cells (often with a small B-cell mantle), with T-cell rosettes, and sometimes with histiocytic granulomas. In diffuse areas of LPHL, tumor cells were also accompanied by small nonneoplastic B cells, but FDC meshworks were lacking. Such areas were associated with typical NLPHL nodules in all but 2 cases that we considered as diffuse LPHL.

In T/HRBCL, the tumor B cells made up less than 10% of the diffuse infiltrate, which was composed mainly of T cells and histiocytes, usually not forming granulomas. No FDC meshworks were detected, and small B cells were rare to absent.

Seventeen cases that did not meet the diagnostic criteria for either NLPHL or T/HRBCL were considered as a third group and analyzed separately.

Clinical data

Data (including age, sex, stage at presentation, B symptoms, tumor diameter, hemoglobin level, serum lactate dehydrogenase level, therapy regimen, and follow-up) on the 105 cases studied in detail were provided by the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (on 46 patients) or by referring clinics and physicians (on 59 patients).

Statistics

Immunophenotypes were compared by χ2 tests by means of Statistica for Windows (Statsoft, Hamburg, Germany) to adopt the comparison to the scales used. Clinical data were also compared by means of Student t test (eg, age), Spearman rank correlation (eg, stage), or log-rank test (eg, survival) depending on the nature of the data. Nominal P values less than .05 were regarded as significant.

Results

Morphology and immunophenotype

The distribution of the diagnoses of all 235 cases is given in Table 1. The remaining 17 cases were in a gray zone, which are detailed in “NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules.” The antigen profiles of tumor cells of NLPHL and T/HRBCL (Table 2) were remarkably similar. Significant differences were restricted to the expression of PU.1, CD79a, and bcl-2. PU.1 was more commonly expressed in NLPHL. On the other hand, CD79a and bcl-2 were more often positive in T/HRBCL.

Distribution of 235 diagnoses in the study

. | Original diagnoses, no. cases . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New diagnoses . | NLPHL, 111 cases . | NLPHL and T/HRBCL with unusual features, 64 cases . | T/HRBCL, 60 cases . | ||

| NLPHL, 139 cases | 108 | 31 | 0 | ||

| T/HRBCL, 79 cases | 0 | 22 | 57 | ||

| NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, 17 cases | 3 | 11 | 3 | ||

. | Original diagnoses, no. cases . | . | . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New diagnoses . | NLPHL, 111 cases . | NLPHL and T/HRBCL with unusual features, 64 cases . | T/HRBCL, 60 cases . | ||

| NLPHL, 139 cases | 108 | 31 | 0 | ||

| T/HRBCL, 79 cases | 0 | 22 | 57 | ||

| NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, 17 cases | 3 | 11 | 3 | ||

Columns count the number of the diagnoses at study entry. Rows give numbers of the definitive diagnoses.

Comparison of the immunohistochemical properties of the tumor cells and of the background between NLPHL, NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte rich-like nodules, and T/HRBCL

Diagnosis . | NLPHL, 53 cases . | P . | NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, 17 cases . | P . | T/HRBCL, 35 cases . | P, NLPHL vs T/HRBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cells | ||||||

| CD20, % | 100 | NS | 100 | NS | 100 | NS |

| CD79a, % | 8 | .03 | 29 | NS | 40 | < .001 |

| J chain, % | 52 | NS | 29 | NS | 46 | NS |

| CD30, % | 6 | NS | 6 | NS | 9 | NS |

| EMA, % | 29 | NS | 35 | NS | 30 | NS |

| BCL-2, % | 4 | NS | 0 | .005 | 40 | < .001 |

| ICSAT, % | 98 | NS | 100 | NS | 94 | NS |

| PU.1, % | 86 | .005 | 53 | NS | 54 | < .001 |

| Background | ||||||

| CD20 | < 1:20 | NS | 1:2.7 | NS | > 1:1.5 | NS |

| CD3 rosettes, % | 89 | NS | 88 | .02 | 57 | < .001 |

| CD4 rosettes, % | 48 | NS | 29 | NS | 15 | .02 |

| CD8 rosettes, % | 0 | NS | 0 | NS | 6 | NS |

| CD57 rosettes, % | 37 | NS | 31 | .018 | 6 | < .001 |

| CD68, % | 66 | .0029 | 94 | NS | 97 | < .001 |

| TIA-1, % | 47 | .034 | 76 | .032 | 86 | < .001 |

| Granzyme B, % | 28 | NS | 35 | .001 | 85 | < .001 |

Diagnosis . | NLPHL, 53 cases . | P . | NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, 17 cases . | P . | T/HRBCL, 35 cases . | P, NLPHL vs T/HRBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor cells | ||||||

| CD20, % | 100 | NS | 100 | NS | 100 | NS |

| CD79a, % | 8 | .03 | 29 | NS | 40 | < .001 |

| J chain, % | 52 | NS | 29 | NS | 46 | NS |

| CD30, % | 6 | NS | 6 | NS | 9 | NS |

| EMA, % | 29 | NS | 35 | NS | 30 | NS |

| BCL-2, % | 4 | NS | 0 | .005 | 40 | < .001 |

| ICSAT, % | 98 | NS | 100 | NS | 94 | NS |

| PU.1, % | 86 | .005 | 53 | NS | 54 | < .001 |

| Background | ||||||

| CD20 | < 1:20 | NS | 1:2.7 | NS | > 1:1.5 | NS |

| CD3 rosettes, % | 89 | NS | 88 | .02 | 57 | < .001 |

| CD4 rosettes, % | 48 | NS | 29 | NS | 15 | .02 |

| CD8 rosettes, % | 0 | NS | 0 | NS | 6 | NS |

| CD57 rosettes, % | 37 | NS | 31 | .018 | 6 | < .001 |

| CD68, % | 66 | .0029 | 94 | NS | 97 | < .001 |

| TIA-1, % | 47 | .034 | 76 | .032 | 86 | < .001 |

| Granzyme B, % | 28 | NS | 35 | .001 | 85 | < .001 |

Markers for tumor cells are given as the percentage of cases expressing the respective antigen in more than a few cells. The rows under “Background” give the percentage of cells/rosettes staining with the respective antibody more than occasionally. The CD20 ratio is the ratio of tumor cells to reactive small B cells. For CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD57, rosettes were evaluated to achieve data of higher reliability. Nominal P values are given only when the difference is statistically significant.

NS indicates not significant.

In contrast to the tumor cell immunophenotype, the background composition of NLPHL and T/HRBCL differed greatly (Table 2): small CD20+ cells dominated in NLPHL, yet CD3+ cytotoxic T-lymphocytes formed the majority of nonneoplastic background in T/HRBCL. However, rosettes of CD3+ lymphocytes around tumor cells were still significantly more frequent in NLPHL than in T/HRBCL. These rosetting lymphocytes in NLPHL were CD4+CD57+ follicular T cells23 that were negative for TIA-1 and granzyme B. Histiocytes were numerous in T/HRBCL, but few to moderate in number in NLPHL. The meshworks of FDCs, while at least partially preserved in NLPHL (with the exception of 2 cases of diffuse NLPHL), were absent in T/HRBCL.

Within NLPHL, the immunophenotype of the tumor cells and background composition correlated with their relationship to FDC meshworks: while tumor cells inside FDC networks showed a higher expression of J chain and PU.1, those outside expressed CD79a and bcl-2 significantly more frequently. In nodular areas, many CD4+CD57+ rosettes were detected, but in diffuse areas histiocytes and cytotoxic T cells were more numerous, but nonetheless significantly fewer than in T/HRBCL.

In 14 cases of otherwise typical T/HRBCL, vaguely nodular areas were detected morphologically and/or immunohistochemically. In only 2 of them (representing fewer than 1% of the cases reviewed), the nodular areas met the criteria of NLPHL also as to the background composition and the occurrence of FDC meshworks. These 2 cases were regarded as T/HRBCL for the comparison of clinical data.

Such lymphomas exhibiting areas of both NLPHL and T/HRBCL need to be distinguished from 17 cases designated gray zone cases, which did not fulfill criteria for either of the entities.

NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules

Seventeen cases (7% of all 235 cases) did not fully meet the diagnostic criteria of either NLPHL or T/HRBCL (Table 1) and therefore could not be readily classified. These tumors consisted of nodules with their FDC meshworks at least partially preserved and of a size similar to those in NLPHL. The tumor cells appeared mostly like L&H cells or large multilobated centroblasts; Reed-Sternberg-like tumor cells were rarely seen. However, variable portions of the lymph nodes, from single nodules in a background of typical NLPHL up to the whole of the specimen, contained peculiar nodules: these attracted attention because, in addition to the tumor cells, they contained abundant T cells and histiocytes, but conspicuously few small B cells.

Numerically, on average 0.7 to 4.2 small B cells were counted per 1 tumor cell (mean, 2.7:1) in T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, similar to T/HRBCL where, by definition, few small B cells were seen (small B cells-to-tumor cells, 0.3:1 to 1.5:1; mean, 0.7:1). In contrast, small B cells outnumbered the tumor cells by 20:1 to 50:1 in NLPHL and by 6:1 in diffuse LPHL.

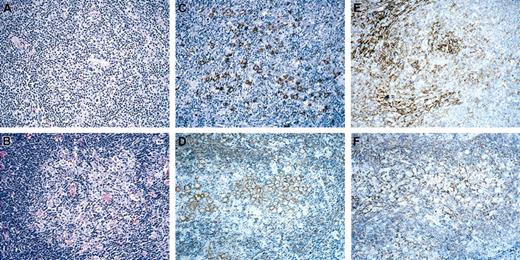

In 10 of the 17 cases, the cellular composition within these nodules resembled T/HRBCL: within vaguely defined nodules neoplastic cells were loosely scattered in a background of small and activated T cells and histiocytes (Figure 1; pattern A, top row). Unlike typical NLPHL, T cells within the nodules were mostly cytotoxic expressing TIA-1, and rosettes of CD4+CD57+ follicular T cells were observed in only one case. FDC meshworks were preserved throughout the follicle.

Patterns of NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules. Pattern A (top row) and pattern B (bottom row). H&E (left column), CD20 (middle column), and CD21 (right column). Original magnification, × 10.

Patterns of NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules. Pattern A (top row) and pattern B (bottom row). H&E (left column), CD20 (middle column), and CD21 (right column). Original magnification, × 10.

In 7 other cases, the tumor cells formed clusters of 5 or more cells within the nodules (Figure 1; pattern B, bottom row), thus rather suggesting DLBCL with a prominent inflammatory background of T cells and histiocytes. However, sheets of blasts reminiscent of follicular lymphoma grade 3b were not observed.24 The nodules were well demarcated and often surrounded by a rim of small B cells, occasionally with histiocytic granulomas. Importantly, no small B cells were seen within the nodules. In 4 of 7 cases, rosettes of CD57+ T cells could be seen within the nodules, and cytotoxic T cells were considerably less frequent than in the cases already described. FDCs were retained mostly at the periphery of the follicle but were hardly seen within the sheets of the tumor cells.

Clinical data

The clinical data are summarized in Table 3. Males were predominantly affected. Patients with NLPHL were significantly younger than those with T/HRBCL (39 versus 49 years). Most patients with NLPHL (80%) presented at stages I and II, but in contrast, 48% with T/HRBCL presented at the advanced stages III or IV. Likewise, B symptoms occurred frequently in patients with T/HRBCL (46%), but only exceptionally in NLPHL (5%). Among NLPHL patients, cases with diffuse areas did not differ in their clinical presentation and outcome from typical NLPHL. The 2 patients with purely diffuse LPHL presented in stages I and II, respectively.

Clinical characteristics of patients with NLPHL, NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, and T/HRBCL

Diagnosis . | NLPHL . | P . | NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules . | P . | T/HRBCL . | P, NLPHL vs T/HRBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. cases | 53 | NS | 17 | NS | 35 | .006 |

| Age, years | 39 | NS | 41 | NS | 49 | < .01 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/L | 142 | NS | 137 | NS | 136 | NS |

| Tumor diameter, cm | 5 | NS | 7 | NS | 7 | NS |

| LDH level, U/L | 205 | NS | 190 | NS | 284 | NS |

| Sex, % male | 68 | < .05 | 94 | NS | 74 | NS |

| Stage, %* | ||||||

| I | 43 | < .005 | 20 | NS | 23 | < .005 |

| II | 37 | < .005 | 20 | NS | 29 | < .005 |

| III | 20 | < .005 | 27 | NS | 26 | < .005 |

| IV | 0 | < .005 | 33 | NS | 22 | < .005 |

| B symptoms, % | 5 | < .001 | 38 | NS | 46 | < .001 |

| Treatment, %* | ||||||

| Surgery only | 6 | .09 | 0 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

| RTx only | 22 | .09 | 15 | .05 | 8 | < .001 |

| COPP/ABVD | 34 | .09 | 15 | .05 | 24 | < .001 |

| BEACOPP | 30 | .09 | 39 | .05 | 8 | < .001 |

| CHOP based | 4 | .09 | 23 | .05 | 60 | < .001 |

| High dose | 0 | .09 | 8 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

| Other | 4 | .09 | 0 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

Diagnosis . | NLPHL . | P . | NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules . | P . | T/HRBCL . | P, NLPHL vs T/HRBCL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. cases | 53 | NS | 17 | NS | 35 | .006 |

| Age, years | 39 | NS | 41 | NS | 49 | < .01 |

| Hemoglobin level, g/L | 142 | NS | 137 | NS | 136 | NS |

| Tumor diameter, cm | 5 | NS | 7 | NS | 7 | NS |

| LDH level, U/L | 205 | NS | 190 | NS | 284 | NS |

| Sex, % male | 68 | < .05 | 94 | NS | 74 | NS |

| Stage, %* | ||||||

| I | 43 | < .005 | 20 | NS | 23 | < .005 |

| II | 37 | < .005 | 20 | NS | 29 | < .005 |

| III | 20 | < .005 | 27 | NS | 26 | < .005 |

| IV | 0 | < .005 | 33 | NS | 22 | < .005 |

| B symptoms, % | 5 | < .001 | 38 | NS | 46 | < .001 |

| Treatment, %* | ||||||

| Surgery only | 6 | .09 | 0 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

| RTx only | 22 | .09 | 15 | .05 | 8 | < .001 |

| COPP/ABVD | 34 | .09 | 15 | .05 | 24 | < .001 |

| BEACOPP | 30 | .09 | 39 | .05 | 8 | < .001 |

| CHOP based | 4 | .09 | 23 | .05 | 60 | < .001 |

| High dose | 0 | .09 | 8 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

| Other | 4 | .09 | 0 | .05 | 0 | < .001 |

P values are given only when the difference is statistically significant (<.05). LDH indicates lactate dehydrogenase; RTx, radiotherapy; COPP, cyclophosphamide vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone; ABVD, adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; BEACOPP, bleomycine, etoposide, doxorubicin, and COPP; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone.

RTx only was given only to patients presenting with stage I disease; high dose indicates high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation.

Patients with NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules presented at an age (median, 41 years) similar to that in typical NLPHL. However, their stages and the frequency of B symptoms were more similar to patients with T/HRBCL; namely, 60% of them presented at advanced stages III or IV and 38% had B symptoms. The 2 patterns did not correlate with sex or with the presence of B symptoms, but the stage was significantly different: patients with the T/HRBCL-like pattern accounted for most of the higher stages (5 of the 9 patients with a known stage were at stage IV, 3 at stage III), while all but one patient (stage III) with the DLBCL-like pattern presented at stages I and II.

Treatment differed significantly with diagnosis and with stage. Among the NLPHL patients, 28% (all stage I) were treated only surgically or by local radiotherapy, while most others were treated with COPP/ABVD or BEACOPP, regimens included in the trials of the German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study. In contrast, 60% of the patients with T/HRBCL were treated with CHOP-based regimen, as is usual in the German High-Grade Lymphoma Study.

Patients with NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules were not treated differently from those with NLPHL if stage is taken into account. Owing to their higher stages, they received intensified regimens more often, and 70% of patients received regimens such as BEACOPP, CHOP, or primary high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation. In contrast, only 34% of patients with NLPHL received a similar therapy because they presented at stage III.

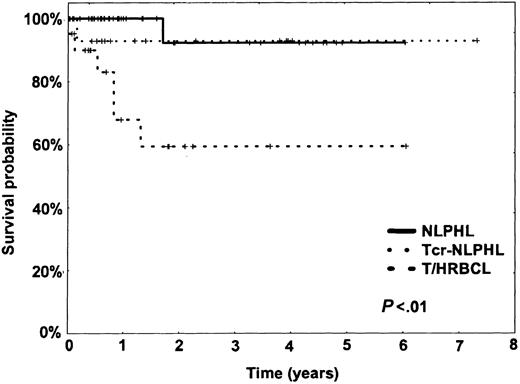

Patients with NLPHL had a very good prognosis; only one patient of the series died after 20 months of myocardial infarction while his lymphoma was in complete remission. Patients with NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules had a similarly good outcome as those with typical NLPHL (Figure 2): only one patient died during treatment. In contrast, patients with T/HRBCL frequently experienced relapse, and 30% of the patients died within the first year (Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier plot of the overall survival (OAS) of NLPHL, NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules (Tcr-NLPHL), and T/HRBCL.

Kaplan-Meier plot of the overall survival (OAS) of NLPHL, NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules (Tcr-NLPHL), and T/HRBCL.

Discussion

NLPHL and T/HRBCL need to be distinguished for treatment purposes; however, criteria are not completely clear in the WHO classification, in terms of either (1) the numbers of tumor cells, the number of reactive B cells, and the degree of nodularity required for the diagnosis of NLPHL or (2) the count of small B cells or nodular areas compatible with T/HRBCL.13 Our immunomorphologic study therefore addressed the clinical significance of architectural patterns and the antigen profile of both tumor cells and nonneoplastic background constituents in a large series of cases.

In NLPHL, most tumor cells had an L&H appearance; RS cells were rarely identified. In T/HRBCL, the neoplastic cells mostly resembled centroblasts, L&H cells, or immunoblasts, but RS cells were scarce. Unlike other authors,10,11 we could not identify strikingly predominating tumor cell variants to subcategorize T/HRBCL according to their morphology.

The immunophenotypic properties of the tumor cells are principally in keeping with previous results.20,25 Both CD79a and bcl-2 were more frequently expressed in T/HRBCL than in NLPHL.26,27 In contrast, PU.1, a transcription factor necessary in early B-cell differentiation, was expressed in NLPHL but reduced in, or absent from, T/HRBCL.21,28 Interestingly, the subtle disparity between the phenotypes of tumor cells seems to reflect their relationship to FDC meshworks. In NLPHL, neoplastic cells inside FDC networks showed a higher expression of J chain and PU.1 than cells in the same tumors that grew diffusely outside; the latter more frequently expressed CD79a and bcl-2. Still, immunophenotypic differences in the tumor cells cannot currently be used for diagnostic purposes.

On the other hand, the reactive background greatly aided the diagnosis. A follicular environment was retained in NLPHL, documented by the presence of meshworks of FDCs, but was absent from T/HRBCL.29 By definition, small B cells are abundant in NLPHL, but rare in T/HRBCL.2 The nature of the T-cell background was diverse20 : in NLPHL, T cells were mainly CD4+CD57+ follicular T cells that commonly formed the rosettes,23 while in T/HRBCL, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells and histiocytes predominated30 and T-cell rosettes were rarely seen.

The clinical characteristics of such defined groups (Table 3) are in accordance with published data.2,31 LPHL with diffuse areas did not present or behave clinically differently from conventional NLPHL. It has been doubted whether diffuse LPHL exists1-3,25 ; however, in our series of 235 lymphomas, we identified 2 such cases: diffusely scattered tumor cells in a background lacking FDCs in the CD21 stain were accompanied by abundant small B cells that distinguished them from T/HRBCL.

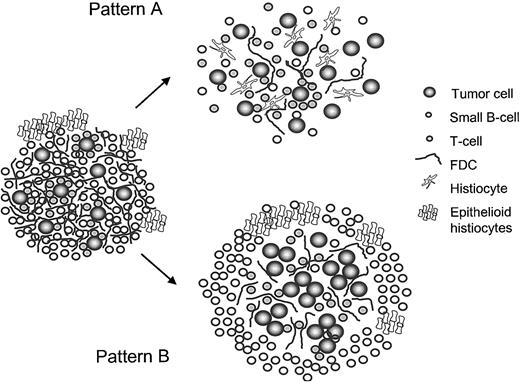

Seventeen cases were clearly in the range between NLPHL and T/HRBCL, but differed from both: the tumor cells grew within nodules defined by FDC meshworks in a T-cell and histiocyte-rich background either singly (T/HRBCL-like pattern A) or in clusters (DLBCL-like pattern B). Small B cells with or without histiocytic granulomas sometimes formed a rim around the follicular structures, but were strikingly absent inside FDC meshworks. Instead, the tumor cells were accompanied by T cells and histiocytes. The occurrence in NLPHL of such nodules with features indistinguishable from histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma has been mentioned previously,32 yet neither their frequency nor their clinical significance has been investigated.

Within these T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules, the growth patterns resembled either T/HRBCL (pattern A) or DLBCL (pattern B) at high magnification (Figures 1 and 3). Pattern A with neoplastic cells scattered loosely in a background of abundant histiocytes and cytotoxic T cells, but with only a scarce number of small B cells, resembled T/HRBCL at high magnification and may be interpreted as an intrafollicular progression toward T/HRBCL. In pattern B, cohesive clusters of large blasts in an inflammatory background could be seen, suggesting a morphologic transformation toward the pattern of DLBCL within the follicles. Especially patients with NLPHL with T/HRBCL-like nodules often presented at a high stage (89% at stage III or IV), while no patient with pattern B showed stage IV, the usual stage being I or II. Conceptually, these patterns may represent different pathways of progression toward DLBCL, which develops in up to 5% of patients with NLPHL.33,34 Interestingly, one half of the DLBCLs occurring in the course of NLPHL are of the T/HRBCL variant.13 This further supports that at least a part of the T/HRBCL may derive from NLPHL and have a follicular origin.10,35

Schematic depiction of the 2 patterns of NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules as possible pathways of morphologic progression of NLPHL.

Schematic depiction of the 2 patterns of NLPHL with T-cell/histiocyte-rich nodules as possible pathways of morphologic progression of NLPHL.

We do not believe that these cases represent an independent disease; rather, the 2 patterns should be regarded as morphologic variants: to refer to the remarkably composed nodules, we propose the descriptive term NLPHL with T-cell-rich nodules. The 2 patterns of these nodules can also be referred to as T/HRBCL-like and DLBCL-like nodules because they appear to have different clinical presentation. Given the excellent prognosis, it will be difficult to decide whether the treatment regimen for Hodgkin lymphoma or for NHL is better suited. Outcome was also excellent when these patients with limited stages were treated with radiotherapy or COPP/ABVD in a stage-adapted regimen for Hodgkin lymphoma. Therefore, its designation as a variant of NLPHL seems appropriate at this time. The recognition of these patterns helps in making decisions in the differential diagnosis, and given their remarkable morphology, the patterns should be reproducible among pathologists. These lymphomas should be recognized and treated in clinical studies to learn more about their biologic behavior and treatment requirements; however, they should probably not be included in studies reducing treatment intensity for NLPHL patients3,25,31 until more evidence regarding their biologic behavior has been accumulated.

In conclusion, in the differential diagnosis between NLPHL and T/HRBCL, all cases exhibiting tumor cells in a meshwork of FDCs should be regarded as NLPHL, regardless of the nature of accompanying small lymphocytes. In diffuse areas, abundant accompanying small B cells characterize a diffuse growth of NLPHL. Only when tumor cells are diffusely scattered in a T-cell and histiocyte-rich background devoid of small B cells, should T/HRBCL be diagnosed. In some cases, areas of both NLPHL and T/HRBCL coincide; these we regard as secondary T/HRBCL progressed from NLPHL.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 24, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0626.

Supported by research grant NC/6037-3 of the Internal Grant Agency of the Czech Ministry of Health (L.B.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal