HEMOSTASIS, THROMBOSIS, AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY

α2-Antiplasmin (α2-AP, also called α2-plasmin inhibitor) is only slowly revealing its full range of subtleties. α2-AP is a member of the serpin family and the principal physiologic inhibitor of plasmin, which it rapidly inactivates. But there is more to α2-AP than its reactive center, because the inhibitor can also bind plasminogen and can be cross-linked to fibrin, both affecting its local action. In plasma, the inhibitor occurs in different forms, reflecting proteolytic cleavage. The inhibitor has a 50-residue C-terminal extension relative to the other serpins. Cleavage in the middle of this extension, by an unknown protease, removes the plasminogen-binding capacity; at any one time the nonbinding form normally constitutes about one third of plasma α2-AP.

In this issue, Lee and colleagues (page 3783) clarify the other and less well-understood variation in α2-AP, which is at the amino-terminus. Originally, α2-AP was thought to have an N-terminal Asn and a 39-residue signal peptide,1 but later work suggested that the mature protein had an additional 12 residues at the amino-terminus, such that the signal peptide was 27 residues. Human plasma contained both the longer (Met-α2-AP) and the shorter (Asn-α2-AP) form, the latter predominating.2 Thus, questions about α2-AP synthesis and processing were raised, and these are answered satisfactorily by Lee and colleagues, who identify the protease that processes α2-AP, antiplasmin-clearing enzyme (APCE). The cleavage between Pro12-Asn13 reveals the cross-linking site (Gln14) in the inhibitor, a site that is essentially cryptic in the mature protein, where the additional 12 residues mask it.

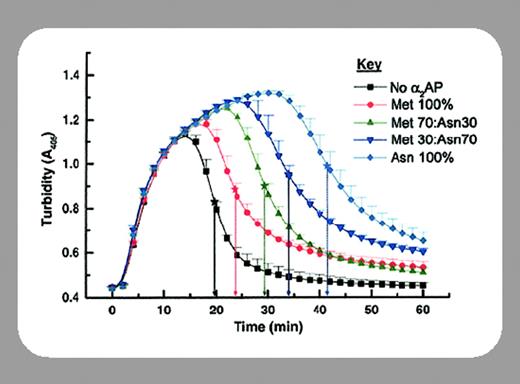

The cross-linking of α2-AP to fibrin by Factor XIIIa is crucial to its function in regulating fibrinolysis. Indeed the abnormality in α2-AP–deficient plasma was illustrated only in fibrin clots prepared in the presence of calcium, which is required for cross-linking. Fibrin from an α2-AP–deficient patient lysed rapidly, even when immersed in normal plasma, proving the efficacy of cross-linked α2-AP.3 Antibodies specific for cross-linked α2-AP greatly stimulated lysis of fibrin.4 The importance of cross-linked α2-AP is sometimes ignored because of emphasis on the relative protection from α2-AP of plasmin formed on the fibrin surface. These apparent contradictions can be reconciled if we consider that the separate effects have been demonstrated in isolation and that the actual physiologic situation will reflect some balance between them. Thus enough local α2-AP will overcome plasmin and vice versa. There are still several questions about the physical interaction between cross-linked α2-AP and fibrin-bound plasmin, but there is no doubt that cross-linking of α2-AP to fibrin decreases fibrinolysis markedly.

The identification of a protease that is closely related to seprase as the α2-AP cleaving enzyme now leads to several important questions. Is the APCE activity expressed in liver cells, where α2-AP is synthesized, or on endothelial cells, where it might act on circulating α2-AP? Is its synthesis regulated in inflammatory or other conditions, such that it might have impact on the local stability of fibrin in the vessel wall? APCE is present in plasma at only trace concentrations and its isolation from plasma is an impressive feat. What is the source of this plasma APCE? The breakthrough by Lee and colleagues in identifying APCE reminds us of the many substrates in the hemostatic system that may be influenced by the emerging families of transmembrane serine proteases5 and the interesting subtleties in regulation that may yet be discovered.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal