Multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) is a distinct lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by lymphadenopathy with angiofollicular hyperplasia and plasma cell infiltration. Patients typically have fever associated with lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, respiratory symptoms, peripheral edema, cytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and high levels of serum C reactive protein (CRP).1 In the context of HIV infection, MCD is associated with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Clinical symptoms correlate with an important increase of KSHV DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).2,3 Vinca alkaloids produce frequent but short-lived responses, and most patients remain dependent upon chemotherapy. Rituximab has been reported to be effective.4 Besides cellular targets, viral targets could be considered for intervention. In vitro, KSHV replication can be inhibited by some antiherpesvirus drugs such as ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir.5

We have read with interest the article by Casper et al6 on the treatment of HIV-associated MCD with ganciclovir. This study, showing a response to ganciclovir in 3 patients, suggested that antiviral agents against KSHV could be used in the management of MCD. However, clinical remission was short lived for patient 2, and patient 1 died with fungal infection after 12 days of ganciclovir. Only the third patient had a long-lasting remission after a 21-day course of valganciclovir. In contrast, our experience with cidofovir (CDV), the most potent anti-KSHV drug in vitro,5 was disappointing. There were 5 HIV-infected patients with histologically proven and chemo-dependent MCD treated prospectively with CDV (5 mg/kg per dose) weekly for 3 weeks and then every other 2 weeks (Table 1). The treatment period was scheduled for 60 days. Chemotherapy was discontinued at entry but was permitted during the study period in case of severe recurring flares. All of the patients had controlled HIV replication on antiretroviral therapy.

Patient characteristics

Patient no. . | No. CD4+ T cells, × 106/L . | KS . | Delay from MCD, diagnosis, mo . | Current therapy for MCD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 320 | + | 47 | Vinblastine |

| 2 | 109 | + | 15 | Etoposide |

| 3 | 701 | + | 52 | Vinblastine |

| 4 | 259 | + | 18 | Vinblastine |

| 5 | 584 | − | 24 | Vinblastine |

Patient no. . | No. CD4+ T cells, × 106/L . | KS . | Delay from MCD, diagnosis, mo . | Current therapy for MCD . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 320 | + | 47 | Vinblastine |

| 2 | 109 | + | 15 | Etoposide |

| 3 | 701 | + | 52 | Vinblastine |

| 4 | 259 | + | 18 | Vinblastine |

| 5 | 584 | − | 24 | Vinblastine |

KS denotes Kaposi sarcoma; MCD, multicentric Castleman disease.

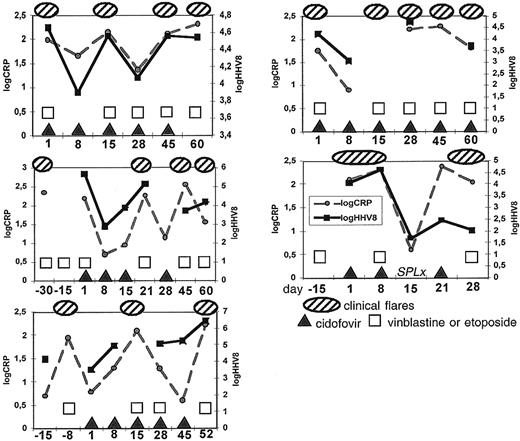

Patients received 3 to 6 CDV infusions over 21 to 60 days. All 5 patients experienced repeated recurrence of MCD symptoms during the study and remained dependent upon chemotherapy. Clinical symptoms were correlated with high serum CRP values and high KSHV copy numbers in PBMCs without any demonstrable impact of cidofovir on these parameters. Patient 5 had no response with an increase of KSHV DNA in PBMCs and was splenectomized, as a diagnosis of lymphoma was suspected. The treatment was prematurely interrupted in 4 patients because of evident failure (Figure 1).

Clinical and virologic features in 5 HIV-infected patients receiving cidofovir for multicentric Castleman disease. Failure in all patients in preventing the recurrence of clinical flares or in reducing the KSHV viral load in PBMCs.

Clinical and virologic features in 5 HIV-infected patients receiving cidofovir for multicentric Castleman disease. Failure in all patients in preventing the recurrence of clinical flares or in reducing the KSHV viral load in PBMCs.

Anecdotal reports of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) responding to antiherpes drugs7 and studies showing that treatment of AIDS patients with ganciclovir or foscarnet for cytomegalovirus disease reduced the risk of KS8 could suggest that antiherpes drugs might be effective against KSHV-associated diseases. Moreover, MCD differs from KS not only in the infected cell type, but also in the pattern of viral gene expression as infected cells from MCD express both latent and lytic proteins.9 This point could argue for a possible direct efficacy of antiviral drugs in KSHV-associated MCD. However, the pathologic features, the frequent evolution of MCD toward KSHV+ non-Hodgkin lymphoma,10 the failure of CDV, and the effectiveness of chemotherapy and rituximab suggest that the profile of this disease remains closer to that of a virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder.

The role of antiviral agents in the treatment of multicentric Castleman disease

We appreciate the interest in our article, “Remission of HHV-8 and HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease with ganciclovir treatment,” and the thoughtful description of 5 patients with multicentric Castleman disease (MCD) by Berezne et al. Their letter characterizes 5 patients with “chemo-dependent” MCD and shows that neither treatment with vinblastine, etoposide, or cidofovir, nor splenectomy, was effective in reducing the frequent flares of MCD.

Of the findings, 2 appeared similar between our study and that of Berezne et al. First, it is notable that the treatment of patient 2 with etoposide had negligible effects, as we observed with 1 patient in our series. Additionally, as first described by Oksenhendler et al,1 both studies found that remission of clinical symptoms is consistently accompanied by declines in human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) viremia, although causality is difficult to infer.

As the pathogenesis of MCD is unclear, especially its relationship to ongoing HHV-8 replication, the role antivirals play in inducing remissions is unknown. The mechanism of viral inhibition is likely to influence the efficacy of an antiviral drug. Ganciclovir and cidofovir both inhibit the secretion of HHV-8 virions after stimulation of latently infected immortalized cells.2,3 In one study, however, cidofovir failed to block the production of early-lytic HHV-8 antigens.4

Our study and the cases described by Berezne et al illustrate the need to evaluate HHV-8 replication in HHV-8- and HIV-associated MCD. Controlled trials of therapies of this infection are warranted and are the best way to define what will emerge as the optimal treatment.

Correspondence: Corey Casper, The University of Washington Virology Research Clinic, 600 Broadway, Suite 600, Seattle, WA 98122; e-mail: ccasper@u.washington.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal