Abstract

There were 50 consecutive idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) adult patients (platelet count < 100 × 109/L) grouped according to positivity or negativity of a solid-phase modified antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test (MACE) against glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa), Ib/IX, and IIa/IIIa. Observation started on the day of MACE assay and lasted at least 6 months. Clinical worsening was defined as the need for starting or modifying therapy because of thrombocytopenia lower than 20 × 109/L or patient admission due to bleeding symptoms. MACE-positive patients had a higher probability of clinical worsening than MACE-negatives (P < .004). The proportion of patients worsening was 18 (72%) of 25 among MACE-positives and 8 (32%) of 25 among MACE-negatives. The median time to clinical worsening was 2.1 months for MACE-positive patients and 27.7 months for MACE-negatives. The assay of specific platelet autoantibodies may be a useful prognostic tool for the clinical course of ITP. (Blood. 2004;103:4562-4564)

Introduction

The diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia, both primary and secondary, is generally accepted to be one of exclusion.1 However, 3 prospective studies indicate that when platelet autoantibodies are detectable, they have a highly positive diagnostic value for immune thrombocytopenia.2-4 However the utility of platelet autoantibodies assay in the clinical course of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is still a matter of debate. Several studies showed that platelet autoantibodies are associated with the severity of the disease.2,5-7 Likewise, reduction or even disappearance of autoantibodies was reported during pharmacologic therapy8 or splenectomy.8-10

We then found it useful to verify by a prospective cohort follow-up study the possible correlation between the presence or absence of platelet autoantibodies, as detected by a solid-phase modified antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test (MACE), and the clinical course of ITP.

Study design

Cohort

Between March 1998 and June 2002, 50 consecutive ITP adult patients were referred to us; 43 were referred primarily and 7 after the diagnosis of ITP had been made elsewhere. At the time of enrollment, 8 patients were on therapy (steroid, danazol, and azathioprine; each alone or in combination); 3 had previously undergone splenectomy; and 39 had no treatment. At 3 to 12 months prior to enrollment, 3 patients had received platelet concentrates for active bleeding and/or severe thrombocytopenia. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Padua University. Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

The diagnostic criteria for ITP were the following: (1) acquired and isolated thrombocytopenia with platelet counts of 100 × 109/L or lower; (2) normal or increased number of bone marrow megakaryocytes; (3) normal spleen size; (4) exclusion of secondary immune and drug-related thrombocytopenia; (5) exclusion of laboratory features of Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV infections; and (6) normal thyroid function test.

ITP was classified as acute or chronic depending on whether it persisted for longer than or fewer than 6 months since diagnosis. Thrombocytopenia was defined as mild for platelet counts between 50 × 109/L and 100 × 109/L, moderate between 20 × 109/L and 50 × 109/L, and severe lower than 20 × 109/L.

All patients had a thorough medical history, underwent complete physical examination, and gave informed consent to the study.

Laboratory determination of specific platelet-associated autoantibodies

A solid-phase modified antigen capture ELISA test was used for the detection of specific platelet-associated autoantibodies against glycoproteins (GP) IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa), Ib/IX, and Ia/IIa (MACE Auto; GTI, Brookfield, WI), as previously described.11

MACE assay was performed in all patients independently during their treatment. The result of MACE assay was unknown to the clinicians until the end of the study, thus not being used for diagnostic or treatment purposes. Patients were categorized as MACE-positives and MACE-negatives according to the presence or absence, respectively, of demonstrable specific platelet-associated autoantibodies.

Clinical outcome and follow-up

For each patient, the observation period started on the day of the assay of platelet autoantibodies and lasted at least 6 months.

The pharmacologic regimens of ITP were the following: 1 mg/kg oral prednisone per day for 4 to 6 weeks tapered until the minimal useful dose to maintain platelet counts higher than 20 × 109/L; 0.4 g/kg intravenous immunoglobulins (IVGGs) over 3 to 5 consecutive days; 400 mg/d danazol for at least 30 consecutive days; 100 mg/d azathioprine for at least 6 weeks tapered to 50 mg/d. Treatment was begun or modified whenever platelet count was lower than 20 × 109/L and/or the patient complained of major bleeding (epistaxis requiring nasal packing, menometrorrhagia, hematuria, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, cerebral bleeding, or hemorrhages requiring red cell and/or platelet transfusions) or minor mucocutaneous bleeding associated with platelet counts lower than 10 × 109/L.

Clinical worsening (CW) of thrombocytopenia was defined as the need for starting or modifying therapy or for hospital admission due to major or minor bleeding associated with platelet counts lower than 10 × 109/L.

Statistical analysis

The Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests were used to compare means and proportions. The cumulative proportion of overall CW-free survivors as a function of time was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier estimator.

Results and discussion

Platelet-associated autoantibodies

Of the patients, 25 (50%) had demonstrable specific platelet-associated autoantibodies (MACE-positives) and 25 had no autoantibodies (MACE-negatives).

Of 25 demonstrable platelet autoantibodies, 10 (40%) were directed against GPIIb/IIIa, 7 (28%) against GPIb/IX, and 8 (32%) against both glycoproteins. Anti-GPIa/IIa antibodies were present in 2 patients together with the anti-GPIIb/IIIa and anti-GPIb/IX antibodies.

MACE-positives and MACE-negatives were comparable for age, sex, platelet count, disease duration, and therapy regimens (Table 1). At the time of enrollment, 12 patients (9 MACE-positive and 3 MACE-negative) had acute ITP, and 38 patients (16 MACE-positive, 22 MACE-negative) had chronic ITP.

Characteristics of MACE-positive and MACE-negative patients

Features . | MACE-positives . | MACE-negatives . |

|---|---|---|

| No. | 25 | 25 |

| Males/females | 6/19 | 10/15 |

| Median age, y (range) | 48 (18-79) | 54 (22-83) |

| Mean platelet count, × 109/L* | 38 ± 33 | 45 ± 24 |

| 0 to 20 × 109/L, no. (%) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) |

| 21 to 50 × 109/L, no. (%) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) |

| 51 to 100 × 109/L, no. (%) | 7 (28) | 11 (44) |

| Mean duration of disease, mos. (range)* | 40 ± 52 (0.5-169) | 54 ± 39 (0.1-149) |

| Median, mos. | 11 | 51 |

| Less than 6 mos., no. (%) | 9 (36) | 3 (12) |

| Mean ± SD, mos. | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 1.5 ± 1.2 |

| More than 6 mos., no. (%) | 16 (64) | 22 (88) |

| Mean ± SD, mos. | 61 ± 54 | 61 ± 36 |

| Patients on therapy at sampling, no. (%) | 3 (12) | 5 (20) |

| Previous splenectomy, no. (%) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) |

| Previous PC infusion, no. (%) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

Features . | MACE-positives . | MACE-negatives . |

|---|---|---|

| No. | 25 | 25 |

| Males/females | 6/19 | 10/15 |

| Median age, y (range) | 48 (18-79) | 54 (22-83) |

| Mean platelet count, × 109/L* | 38 ± 33 | 45 ± 24 |

| 0 to 20 × 109/L, no. (%) | 9 (36) | 5 (20) |

| 21 to 50 × 109/L, no. (%) | 9 (36) | 9 (36) |

| 51 to 100 × 109/L, no. (%) | 7 (28) | 11 (44) |

| Mean duration of disease, mos. (range)* | 40 ± 52 (0.5-169) | 54 ± 39 (0.1-149) |

| Median, mos. | 11 | 51 |

| Less than 6 mos., no. (%) | 9 (36) | 3 (12) |

| Mean ± SD, mos. | 2.3 ± 1.9 | 1.5 ± 1.2 |

| More than 6 mos., no. (%) | 16 (64) | 22 (88) |

| Mean ± SD, mos. | 61 ± 54 | 61 ± 36 |

| Patients on therapy at sampling, no. (%) | 3 (12) | 5 (20) |

| Previous splenectomy, no. (%) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) |

| Previous PC infusion, no. (%) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

Mean ± SD.

Clinical worsening analysis

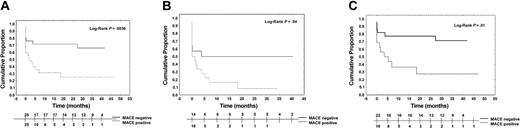

The Kaplan-Meier curve analysis showed that MACE-negative patients had a lower probability of CW than the MACE-positives (P < .004; Figure 1A). CW probability was lower in MACE-negative patients even when considering those with a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L (14 of 25 vs 18 of 25; P < .05; Figure 1B) or those with chronic thrombocytopenia at the time of study start (22 of 25 vs 16 of 25; P = .01; Figure 1C).

Cumulative proportion of clinical worsening among the cohort of patients (Kaplan-Meier estimate) and the subgroups. The estimate curve of all patients (A) shows in MACE-positive patients a higher probability of clinical worsening than that of MACE-negatives. The same results are obtained also by the estimate curves of the subgroup of patients with a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L at enrollment (B) and considering only the 38 patients with the chronic form of ITP (C).

Cumulative proportion of clinical worsening among the cohort of patients (Kaplan-Meier estimate) and the subgroups. The estimate curve of all patients (A) shows in MACE-positive patients a higher probability of clinical worsening than that of MACE-negatives. The same results are obtained also by the estimate curves of the subgroup of patients with a platelet count lower than 50 × 109/L at enrollment (B) and considering only the 38 patients with the chronic form of ITP (C).

The proportion of patients with CW was 72% (18 patients) among MACE-positives and 32% (8 patients) among MACE-negatives. The median time to CW was 2.07 months (range, 0.03 to 47.21 months) for MACE-positive patients, and 27.35 months (range, 0.03 to 41.98 months) for MACE-negatives after enrollment.

The specificity of platelet autoantibodies was 7 (39%) of 18 anti-GPIIb/IIIa, 4 (22%) of 18 anti-GPIb/IX, and 7 (39%) of 18 toward both glycoproteins in those with CW and 3 (43%) of 7 anti-GPIIb/IIIa, 3 (43%) of 7 anti-GPIb/IX, and 1 (14%) of 7 toward glycoproteins IIb/IIIa, Ib/IX, and Ia/IIa in those without CW.

Among the 18 MACE-positive patients who had CW, 11 had hospital admission related to thrombocytopenia, 2 had therapy changed, and 5 were started on therapy because of progressive falling of platelet count. All 3 MACE-positive patients on therapy at enrollment had CW.

Among the 8 MACE-negative patients with CW, 4 had hospital admission related to ITP, 1 had therapy changed, and 3 were started on therapy because of severe thrombocytopenia. Of 5 MACE-negatives on therapy at the time of enrollment and those who had undergone splenectomy, 3 had CW.

In spite of evidence of the role of platelet autoantibodies as detected by phase 3 assays, they are so far considered unnecessary in the setting of immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP).

In our series, thrombocytopenia recurred in 72% of MACE-positives and in only 32% of MACE-negatives after a mean time of 2.1 and 27.7 months, respectively.

Platelet autoantibodies were more frequently found in patients with active ITP,5,6 and a relationship has been reported between their level and response to therapy.8-10 The effect of therapy on the following clinical course cannot be evaluated in our series due to the low number of patients receiving drugs prior to enrollment.

Since the degree of thrombocytopenia and its short duration may also affect the clinical course of ITP,12 we also analyzed subgroups of patients with moderate-severe thrombocytopenia and patients with chronic disease at enrollment. Such further analysis validates the higher incidence of CW in patients with detectable platelet autoantibodies.

In accord with previous reports,3,11,13,14 40% of demonstrable platelet autoantibodies were against GPIIb/IIIa, 28% were against GPIb/IX, and 32% were against both antigens in our series. Finally, it has been suggested that antibody specificity might help in predicting the course of ITP: in fact, patients with antibodies against GPIb/IX or multiple antigens have been reported to suffer from more severe bleeding symptoms, lower platelet counts, and a poor response to steroids.6,7,15 In our series, the specificity of autoantibodies was not correlated with the clinical outcome, but this can be due to the relatively low number of patients.

In conclusion, this study seems to support for the first time evidence that ITP patients with platelet autoantibodies, as detected by MACE, have a CW of thrombocytopenia more frequently and sooner than patients without autoantibodies.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 19, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3352.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears in the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal