Abstract

Using intracellular p24 staining to discriminate between bystander and HIV productively infected cells, we evaluated the properties of HIV productively infected cells in terms of cytokine expression, activation status, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. We demonstrate that HIV productively infected primary CD4+ T cells express 12- to 47-fold higher type 1 cytokines than bystander or mock-infected cells. The frequency of HIV productive replication occurred predominantly in T-helper 1 (Th1), followed by Th0, then by Th2 cells. These productively infected cells expressed elevated levels of CD95, CD25, CXC chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4), and CC chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5). While productively infected cells were only 1.8-fold higher in apoptosis frequency, they up-regulated the antiapoptotic protein B-cell leukemia 2 (Bcl-2) by 10-fold. Up-regulation of interleukin-2 (IL-2) and Bcl-2 were dependent on phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signal transduction, given that it was down-regulated by Wortmanin treatment. Additionally, 60% of productively infected cells entered the cell cycle, as evaluated by Ki67 staining, but none divided, as evaluated by carboxyfluoresccin diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) staining. Evaluation of cell cycle progression by costaining for DNA and RNA indicated that the cells were arrested in G2/M. Collectively, these data indicate that HIV replication occurs predominantly in Th1 cells and is associated with immune activation and up-regulation of Bcl-2, conferring a considerable degree of protection against apoptosis in the productively infected subpopulation. (Blood. 2004;103:4581-4587)

Introduction

The interaction between cytokines and HIV expression is multifaceted. Approaches to evaluate the relationship between cytokines and HIV have relied on (1) evaluating the impact of a particular cytokine on HIV replication in vitro,1-5 (2) comparing the cytokine expression profile of HIV-infected and uninfected donors,6,7 and (3) measuring cytokine production from in vitro infected cells.8-10

Analysis of the impact of cytokines on HIV-1 replication in vitro have generally demonstrated that a number of type 1 cytokines (interleukin-1 [IL-1], tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α], IL-2, IL-12) up-regulate HIV replication while type 2 cytokines down-modulate HIV (IL-10, transforming growth factor-β [TGF-β]). This relationship is not simplistic given that a combination of type 1 and type 2 cytokines may lead to a synergistic or antagonistic effects on HIV replication11-14 ; this result often depends on the combination of cytokines and on the cell type examined, whether lymphocytic or monocytic.

Earlier studies describing the cytokine profile in purified peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from HIV+ patients have led to discordant findings. Some suggested that HIV-1 infection leads to a shift from type 1 (IL-2, interferon-γ [IFN-γ]) to type 2 (IL-4, IL-10) cytokines with HIV disease progression.6 By contrast, others have not been able to document such a type 1-to-type 2 cytokine shift with disease progression,15,16 and yet others have reported that HIV-1 induces a shift from Th1 to Th0 response.17,18 These discordant findings have prompted studies to determine whether Th0, Th1, or Th2 subsets were preferentially infected by HIV-1. Again, discordant data have been published, as some suggested preferential replication in Th2/Th0 versus Th1 cells17-19 and others did not observe a difference between HIV infectivity of Th1 and Th2 subsets.20

The 3 approaches described to elucidate the relationship between cytokines and HIV replication have one major limitation in that these studies did not discriminate between HIV-infected cells and bystander cells. Bystander cells are defined as cells that have been exposed to HIV but do not actively replicate the virus. These bystander cells may skew the overall cytokine profile of infected populations and may have led to the discordant published reports attempting to delineate the relationship between cytokines and HIV.

Given that studies evaluating the relationship between cytokines and HIV did not discriminate the effects of productively infected cells from those of bystander cells, we used advanced intracellular flow cytometric analyses to discriminate between HIV-infected and bystander cells. This discrimination was based on intracellular expression of HIV-1 core antigen (p24), whereby productively infected cells were defined as p24+ and bystander cells as p24-. This type of evaluation allowed us, for the first time, to determine the properties of productively infected cells, including Th1/Th2 cytokine expression, immune activation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation.

Materials and methods

Isolation of PBMCs and primary CD4+ T cells

PBMCs from healthy blood donors were isolated by density gradient centrifugation from heparin-treated blood within 1 hour after venipuncture. Primary CD4+ T cells were isolated by positive magnetic immunoselection by means of an automated bench-top cell sorter (autoMACS; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Briefly, 107 freshly isolated PBMCs were incubated at 4°C with anti-CD4 microbeads for 20 minutes in binding buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS], pH 7.2; 0.5% bovine serum albumin; and 2 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid]). The labeled cells were then passed through a magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS) column on the autoMACS, and positively selected cells were eluted. All cells were propagated in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 20 U/mL IL-2 (National Institutes of Health [NIH] AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Rockville, MD). Human research was conducted in accordance with the approval of Rush University Medical Center's Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was provided according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

HIV-1 infection

The initial stock of HIV IIIB was obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program and was then used to grow more of the virus by inoculating H9 cells (NIH AIDS Research and Reagent Program) with HIV IIIB. At 6 days after infection, the supernatant containing the virus was collected by centrifugation. Then, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added to the viral supernatant, and aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen until p24 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to determine the amount of HIV p24 present in these aliquots. PBMCs or purified CD4+ T cells were then infected with HIV IIIB at 20 ng p24 per 2 × 106 cells for 4 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, HIV-exposed cultures or mock-infected cultures were washed twice to remove unbound virus and were cultured in the presence of IL-2 (20 U/mL). Mock infection consisted of adding the same amount of medium as that containing the HIV inoculum and handling the cells in a fashion similar to those infected cultures. The following day, cells were stimulated with 2 μg/mL anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies and incubated until p24 detection and cytokine expression analysis. HIV-1 infection was monitored by quantitation of p24 antigen in culture supernatants by means of an HIV-1 p24 ELISA (AIDS Vaccine Program, Frederick, MD) or intracellular staining for HIV p24, as described in the next section.

Immunostaining and flow cytometric analysis of intracellular proteins and/or DNA

Anti-IL-2, anti-IL-4, anti-IL-10, anti-IFN-γ, anti-CD4, anti-CD3, anti-CD25, anti-CD95, anti-B-cell leukemia 2 (anti-Bcl-2), Ki67, anti-CXC chemokine receptor 4 (anti-CXCR4), and anti-CC chemokine receptor 5 (anti-CCR5) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) conjugated to phycoerythrin (PE), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), or allophycocyanin (APC) as indicated were purchased from Becton Dickinson-PharMingen (San Jose, CA). Intracellular staining of HIV-p24 was performed by means of the FIX & Cell Permeabilization kit (CALTAG Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Briefly, cells were fixed and permeabilized in the presence of anti-p24-FITC or anti-p24-PE at the recommended concentrations (Coulter, Miami, FL). Stained and fixed cells were kept at +4°C for 10 minutes prior to flow cytometric analysis. Intracellular protein staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences-PharMingen), after blockade of protein secretion with the use of Brefeldin A (BFA) solution (BD Biosciences-PharMingen) for 6 hours. DNA was immunostained either with propidium iodide (PI) alone at 5 μg/mL or with costaining with 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) and pyronin. Costaining was performed by first fixing/permeabilizing the cells and then incubating the cells with the 7AAD solution for 5 to 10 minutes, followed by 25 μg/mL pyronin with anti-p24-FITC. The cells were then incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed and resuspended in 2% formaldehyde for flow analysis. All immunostained samples were analyzed by means of a 4-color flow cytometer (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson) by gating on the live lymphocyte gate. CD3, CD4, or CD8 (with FITC, PE, PerCP, and APC) was used to compensate for overlapping signals. Appropriate isotype antibodies were also used as negative controls. Data analyses were performed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

TUNEL (transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling) assay

DNA fragmentation was measured by the in situ death detection kit-fluorescein (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Briefly, cells were permeabilized with 1 × FACS Permeabilizing Solution (BD Biosciences) for 10 minutes and vigorously washed. The cells were then incubated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) conjugated to FITC to label the low-molecular weight DNA fragments (mononucleosomes and oligonucleosomes) and single-strand breaks (nicks) in high-molecular weight DNA at 37°C for 1 hour along with anti-p24-PE or other markers as indicated. In all experiments, a negative control consisting of incubating cells with the enzyme solution or a positive control consisting of incubating permeabilized cells with DNAse I solution was performed. Fluorescent signals were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-k/Akt) signal transduction cascade

Wortmanin (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 1 mM and used at a final concentration of either 1 μM or 100 nM in the cell-culture medium. Cells were incubated with Wortmanin overnight before flow cytometry analysis.

Cell proliferation by carboxyfluoresccin diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) tracking

Cells were washed with PBS and resuspended at 106/mL in PBS supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to the cells at 10 μM for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Labeled cells were extensively washed, seeded in complete RPMI, and cultured at 37°C for 5 days. Labeled cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry at the time points indicated.

Statistical analysis

The κ2 test was used to compare the percentage of expression of the various extracellular or intracellular proteins in uninfected, HIV+/p24- (bystander), and HIV+/p24+ (productively infected) subpopulations. Statistical significance was set at P less than .05.

Results

HIV productive infection is found in CD4+ primary T cells and PBMCs expressing elevated levels of type 1 and type 2 cytokines

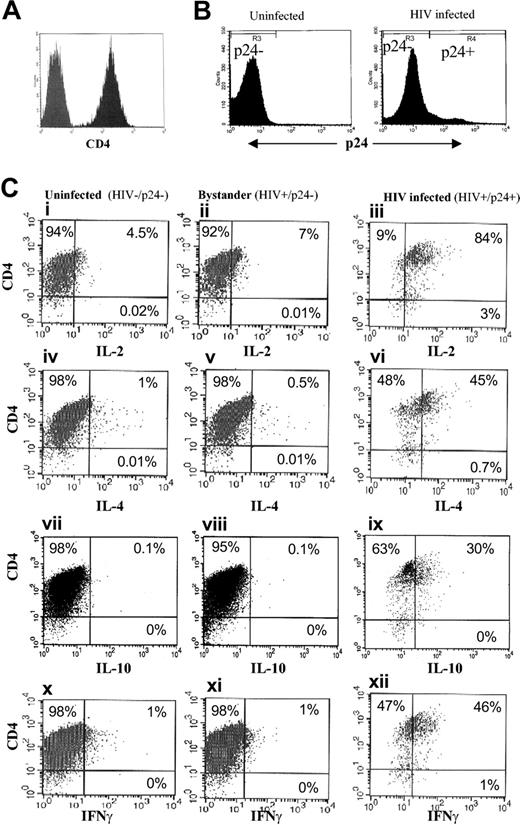

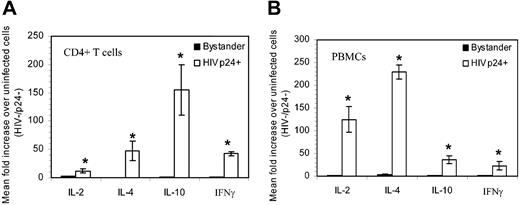

To determine the cytokine profile of the subpopulation of CD4+ primary T cells that are actively replicating HIV, CD4+ T cells were isolated from the PBMCs of healthy donors with the use of magnetic immunoselection. CD4+ T cells were routinely enriched by 90% to 98%, as evaluated by flow cytometry (Figure 1A). The purified cells were then mock infected or infected with HIV and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 at 24 hours after infection. At 7 days after infection, the cells were stained for surface CD4, intracellular p24, and either intracellular IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFN-γ expression to enable the discrimination of cytokine expression in the p24- or p24+ subpopulations (Figure 1B). Cytokine expression was then compared in uninfected/mock-infected cells, defined as HIV-/p24-; bystander cells, defined as those exposed to HIV but p24- (HIV+/p24-), and productively infected cells, defined as HIV+/p24+. As seen in dot plot analysis from one representative donor, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ expressions were all dramatically elevated in the HIV productively infected subpopulation (HIV+/p24+) in comparison with either bystander or uninfected cells (Figure 1C). Cumulative data from at least 3 donors demonstrate that IL-2 expression was 12-fold, IL-4 expression was 47-fold, IL-10 expression was 155-fold, and IFN-γ expression was 43-fold higher in HIV+/p24+ fractions than in uninfected cells (Figure 2A). These values were all significant, with P < .05. The dramatic fold increase of IL-10 expression in the HIV productively infected cells was due predominantly to the extremely low level (0.1%) of IL-10 expression in the bystander or uninfected subpopulations. The same trend was observed with the use of infected PBMCs and gating on either p24+ or p24- fractions along with costaining for type 1 and type 2 cytokines (Figure 2B). In both CD4+ T cells and PBMCs, it seems that HIV productively infected cells demonstrate the following hierarchy of cytokine expression: IL-2 is greater than IFN-γ, which equals IL-4, which is greater than IL-10, with IL-10 rarely detected in uninfected CD4+ T cells and IL-4 rarely detected in uninfected PBMCs.

Cytokine expression in productively infected cells. (A) Enrichment of CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were enriched by positive immunoselection from healthy donors. Left histogram represents isotype-matched controls, and right histogram represents CD4 after selection. (B) Discrimination between p24+ and p24- fractions. Purified CD4+ T cells were either mock infected or infected with HIV and then stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. At 6 days after infection or mock infection, the cells were stained for intracellular p24. (C) Cytokine expression in the 3 subpopulations. Infected CD4+ T cells were treated as described for panel B and stained for surface CD4 and intracellular IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFN-γ along with HIV p24. Data are from 1 donor, representative of at least 3 donors.

Cytokine expression in productively infected cells. (A) Enrichment of CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were enriched by positive immunoselection from healthy donors. Left histogram represents isotype-matched controls, and right histogram represents CD4 after selection. (B) Discrimination between p24+ and p24- fractions. Purified CD4+ T cells were either mock infected or infected with HIV and then stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28. At 6 days after infection or mock infection, the cells were stained for intracellular p24. (C) Cytokine expression in the 3 subpopulations. Infected CD4+ T cells were treated as described for panel B and stained for surface CD4 and intracellular IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFN-γ along with HIV p24. Data are from 1 donor, representative of at least 3 donors.

Cytokine expression in uninfected, bystander, and HIV productively infected subpopulations of CD4+ T cells and PBMCs. Cells were purified as described in “Materials and methods,” infected with HIV, and immunostained for CD4, HIV p24, and either IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFN-γ. Data represent mean fold increase over mock/uninfected cells from at least 3 different donors. *P < .05.

Cytokine expression in uninfected, bystander, and HIV productively infected subpopulations of CD4+ T cells and PBMCs. Cells were purified as described in “Materials and methods,” infected with HIV, and immunostained for CD4, HIV p24, and either IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, or IFN-γ. Data represent mean fold increase over mock/uninfected cells from at least 3 different donors. *P < .05.

HIV productively infected cells are predominantly associated with Th1 rather than Th0 or Th2, cells

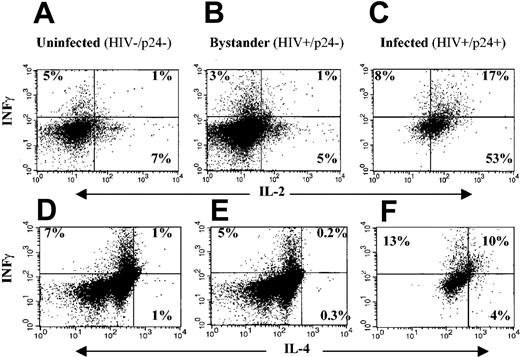

Given that, on the basis of single-cytokine staining, a great proportion of cells harboring productively replicating HIV (HIV+/p24+ subpopulation) expressed elevated levels of type 1 and type 2 cytokines, we costained for type 1 and type 2 cytokines along with HIV p24 to examine whether the subpopulation harboring HIV is in Th0, Th1, or Th2 cells. CD4+ T cells or PBMCs were mock infected or infected with HIV and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28, as described previously. Even after a second round of anti-CD3/CD28 costimulation, Th0 and Th2 subsets in uninfected and bystander subpopulations still remained rare and did not exceed 1% in both CD4+ T cells (Figure 3A-B,D-E) and PBMCs (data not shown). In contrast, 70% of productively infected cells were positive for both IL-2 and IFN-γ (Figure 3C), and only 10% of the population exhibited a Th0 profile, as indicated by dual expression of IL-4 and IFN-γ (Figure 3F). Th2 cells constituted 4% of productively infected CD4+ T cells (Figure 3F). From these data, based on the percentage of cytokine expression in productively infected cells, HIV productive infection seems to occur predominantly in Th1 cells and follows this hierarchy: Th1 (sum of IL-2+IFN-γ+ and IL-2+IFN-γ-) is greater than Th0 (IFN-γ+IL-4+), which is greater than Th2 (IFN-γ-IL-4+). A similar pattern of HIV productive replication in the 3 compartments was observed with the use of PBMCs, where 84% of HIV+/p24+ cells were in Th1, 23% were in Th0, and 3% were in Th2 cells (data not shown).

Frequency of Th0, Th1, and Th2 cells in uninfected, bystander, and productively infected CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were enriched and infected with HIV as described. Cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours prior to Brefeldin A treatment and staining for HIV p24 and IFN-γ plus IL-2 or with IFN-γ plus IL-4. (A,D) Mock-infected cells. (B,E) Bystander cells. (C,F) HIV productively infected cells. Data are representative of at least 3 donors.

Frequency of Th0, Th1, and Th2 cells in uninfected, bystander, and productively infected CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells were enriched and infected with HIV as described. Cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 for 24 hours prior to Brefeldin A treatment and staining for HIV p24 and IFN-γ plus IL-2 or with IFN-γ plus IL-4. (A,D) Mock-infected cells. (B,E) Bystander cells. (C,F) HIV productively infected cells. Data are representative of at least 3 donors.

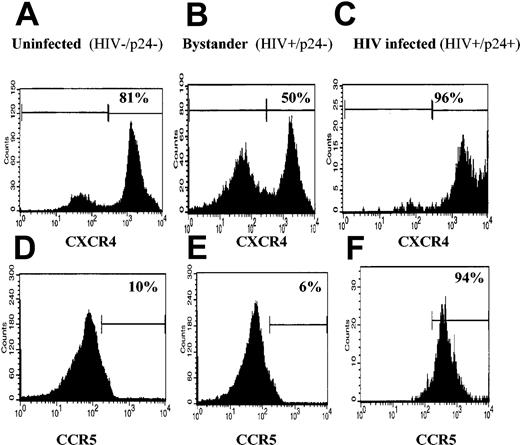

Enhanced expression of HIV-1 coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5 in cells productively replicating HIV-1

Given that Th1 cytokines up-regulate CCR5 and down-regulate CXCR4 expression21,22 while Th2 cytokines up-regulate CXCR4 and down-regulate CCR5 expression,21,23,24 we evaluated CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on the subpopulations of enriched CD4+ T cells that were mock infected, bystander, and productively infected. CXCR4 expression was high on mock-infected cells (81%, Figure 4A), down-regulated on the bystander population to 50% (Figure 4B), but substantially up-regulated on productively infected cells; 96% of HIV+/p24+ cells were positive for CXCR4 expression (Figure 4C). Also, only 10% of CD4+ T cells were positive for CCR5 (Figure 4D). CCR5 expression was not significantly changed in the bystander population (Figure 4D) but, like CXCR4 expression, was dramatically up-regulated on productively infected cells, 94% of which were now positive for CCR5 expression (Figure 4F).

CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on uninfected, bystander, and productively infected cells. CD4+ T cells were isolated and infected as indicated earlier. The cells were then stained for p24 and CXCR4 or CCR5. (A,D) Mock-infected cells. (B,E) Bystander cells. (C,F) HIV productively infected cells. Histograms shown are representative of 3 donors.

CXCR4 and CCR5 expression on uninfected, bystander, and productively infected cells. CD4+ T cells were isolated and infected as indicated earlier. The cells were then stained for p24 and CXCR4 or CCR5. (A,D) Mock-infected cells. (B,E) Bystander cells. (C,F) HIV productively infected cells. Histograms shown are representative of 3 donors.

Cells productively replicating HIV-1 are activated, undergo limited apoptosis, are blocked at G2/M, and do not undergo cell division

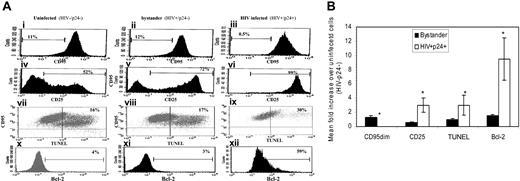

To further characterize the phenotypic properties of CD4+ T cells actively replicating HIV, we compared the activation status, apoptosis, and proliferation rate of cells that are actively replicating HIV with uninfected or bystander subpopulations. Cell activation was evaluated by examining the expression of 2 activation markers, CD95 and CD25. Dim expression of CD95 is associated with the naive/unprimed status of a cell. Uninfected and bystander cells expressed approximately 11% CD95dim (Figure 5Ai-ii). Productively infected cells, however, down-regulated CD95dim expression to 0.5%, representing up-regulation of CD95high (Figure 5Aiii). CD25 expression was also markedly up-regulated on productively infected cells; 99% of HIV+/p24+ cells expressed CD25, and only 52% of uninfected cells and 72% of bystander cells were positive for CD25 (Figure 5Aiv-vi).

Phenotypic characterization of HIV-infected subpopulation. (A) CD4+ T cells were infected as described. The cells were immunostained for p24 and CD95 (i-iii), CD25 (iv-vi), TUNEL and CD95 (vii-ix), or Bcl-2 (x-xii). Expression of each marker in uninfected, bystander, and HIV-infected populations is shown from one representative donor. (B) Mean fold increase of each marker in panel A over HIV-uninfected cultures from 3 donors. *P < .05.

Phenotypic characterization of HIV-infected subpopulation. (A) CD4+ T cells were infected as described. The cells were immunostained for p24 and CD95 (i-iii), CD25 (iv-vi), TUNEL and CD95 (vii-ix), or Bcl-2 (x-xii). Expression of each marker in uninfected, bystander, and HIV-infected populations is shown from one representative donor. (B) Mean fold increase of each marker in panel A over HIV-uninfected cultures from 3 donors. *P < .05.

Apoptosis was evaluated by the TUNEL assay. Bystander and mock-infected cells underwent a similar rate of apoptosis: approximately 16% (Figure 5vii-viii). The frequency of apoptotic cells in HIV productively infected cells was at 30%, which is equivalent to only a 1.8-fold increase in apoptosis over uninfected or bystander cells (Figure 5Avii-ix). This seemingly low level of apoptosis in HIV productively infected cells correlated with the up-regulation of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-2 (Figure 5Ax-xii). The level of Bcl-2 up-regulation in HIV productively infected cells represented a 10-fold increase in Bcl-2 expression over uninfected or bystander cells. (Figure 5B).

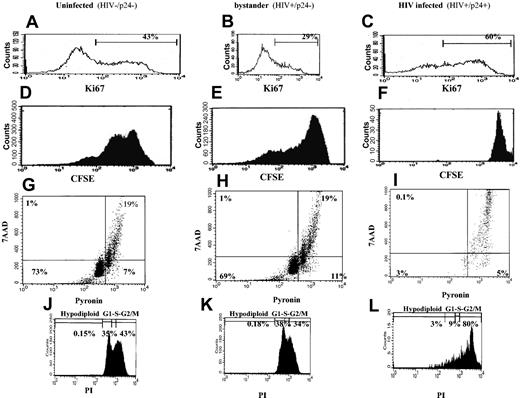

We evaluated cell proliferation by staining for Ki67 and CSFE. As shown in Figure 6A-C, 60% of HIV productively infected cells were Ki67+, compared with 29% Ki67+ in the bystander population and 43% Ki67+ in the uninfected population. These data indicate that a greater percentage of productively infected cells have entered the cell cycle than uninfected or bystander cells. Bystander cells were least likely to have entered the cell cycle. Given that Ki67 measures only entry into the cell cycle and not necessarily completion of the cell cycle, we evaluated cell division by CFSE staining. Both uninfected cells and bystander cells underwent approximately 4 cycles of cell division, while HIV productively infected cells did not divide (Figure 6D-F). Evaluating the stage at which the cells were arrested in the cell cycle by dual DNA/RNA costaining (7ADD/pyronin, respectively) revealed that 91% of productively infected cells were arrested at the S/M stage of the cell cycle (Figure 6I), whereas uninfected and bystander cells were comparable in cell cycle progression (approximately 19% were in S/M, Figure 6G-H). Propidium iodide (PI) staining revealed that the productively infected cells were arrested specifically in G2/M (Figure 6J-L). CFSE tracking data, when taken with the analysis of cell cycle progression, indicate that HIV productively infected cells enter the cell cycle but do not complete it, as they are arrested in the G2/M stage.

Evaluation of cell cycle progression in HIV productively infected cells. CD4+ isolated and infected cells were stained with p24 and Ki67 (A-C), p24 and CSFE (D-F), p24 and 7AAD/pyronin (G-I), or p24 and PI (J-L) to discriminate between bystander and HIV-infected subpopulations. Uninfected cells were treated and stained similarly. Histograms are of data from 1 donor, representative of at least 3 donors. In panels G-I, the lower left quadrant designates cells in G0; lower right quadrant designates cells in G1; and upper right quadrant designates cells in S/M stage of the cell cycle. In panels J-L, the first peak designates hypodiploid cells; the second peak is G1; the third peak is S, and the fourth peak is the G2/M stage.

Evaluation of cell cycle progression in HIV productively infected cells. CD4+ isolated and infected cells were stained with p24 and Ki67 (A-C), p24 and CSFE (D-F), p24 and 7AAD/pyronin (G-I), or p24 and PI (J-L) to discriminate between bystander and HIV-infected subpopulations. Uninfected cells were treated and stained similarly. Histograms are of data from 1 donor, representative of at least 3 donors. In panels G-I, the lower left quadrant designates cells in G0; lower right quadrant designates cells in G1; and upper right quadrant designates cells in S/M stage of the cell cycle. In panels J-L, the first peak designates hypodiploid cells; the second peak is G1; the third peak is S, and the fourth peak is the G2/M stage.

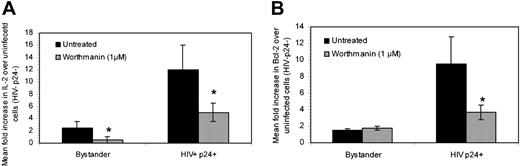

Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signal transduction cascade reduces IL-2 and Bcl-2 expression in HIV productively replicating cells

To initially evaluate the pathway that led to the up-regulation of IL-2 and Bcl-2 expression, CD4+ T cells were infected or mock infected and treated with either 1 μM or 100 nM Wortmanin. Wortmanin mediates the inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signal transduction cascade, which is common to γ-chain signaling events. As seen in Figure 7, Wortmanin reduced IL-2 expression in both bystander and HIV productively infected cells by 5- and 2-fold, respectively (Figure 7A). Wortmanin treatment also down-regulated Bcl-2 expression by 3-fold in productively infected cells (Figure 7B) but did not affect bystander expression, given that Bcl-2 expression in bystander cells was equivalent to that in uninfected cultures (Figure 5Ax-xi). These data indicate that the pathway to IL-2 and Bcl-2 up-regulation in HIV productively cells is partially dependent on phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase signaling events. The fact that inhibition of IL-2 and Bcl-2 expression was not complete suggests that other signaling pathways may be playing a role in these up-regulatory events.

Impact of Wortmanin treatment on IL-2 and Bcl-2 expression. CD4+ T cells were isolated and either mock infected or infected as described in “Materials and methods.” The cells were then left untreated or treated with Wortmanin. Expression of IL-2 (A) and Bcl-2 (B) were determined in uninfected, bystander (HIV+/p24-), or HIV productively infected cells (HIV+/p24+). Data are presented as mean fold increase of IL-2 or Bcl-2 over uninfected cells and are representative of 3 experiments. *P < .05 between each untreated and Wortmanin-treated subpopulation.

Impact of Wortmanin treatment on IL-2 and Bcl-2 expression. CD4+ T cells were isolated and either mock infected or infected as described in “Materials and methods.” The cells were then left untreated or treated with Wortmanin. Expression of IL-2 (A) and Bcl-2 (B) were determined in uninfected, bystander (HIV+/p24-), or HIV productively infected cells (HIV+/p24+). Data are presented as mean fold increase of IL-2 or Bcl-2 over uninfected cells and are representative of 3 experiments. *P < .05 between each untreated and Wortmanin-treated subpopulation.

Discussion

The majority of previous studies that have independently evaluated the impact of HIV on key cellular properties such as cytokine expression, cell activation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation have not discriminated between HIV productively infected cells and those that have been exposed to HIV yet are not infected. These cells are referred to here as bystander cells. The inability to discriminate between these 2 subpopulations may have led to the masking of specific responses, predominantly because HIV-infected cells often constitute a minority of the overall infected population in vitro.

Few studies have discriminated between infected and bystander cells, but those studies have relied on infection with a molecular clone of HIV, often depleted in nef and replaced with a reporter such as the green fluorescent protein,25 mouse heat-stable antigen,26,27 or surface protein placental alkaline phosphatase.28 Because these molecular clones are depleted in nef, a physiologic response due to the whole intact virus may not be delineated. In this report, we infected primary CD4+ T cells or PBMCs with intact HIV and discriminated between HIV productively infected cells and bystander subpopulations on the basis of intracellular expression of HIV p24.

Examining the properties of productively infected cells in terms of cytokine profile, activation status, rate of apoptosis, and rate of proliferation in comparison with bystander and uninfected cells indicated that HIV productive infection occurs predominantly in Th1 cells. A small percentage of HIV productively infected cells were in the Th0 population, followed by Th2, which represented the least frequent phenotype in which we detected productive HIV replication. Two possible explanations emerge from these experiments. HIV may be up-regulating Th1 cytokines or, alternatively, HIV may be preferentially replicating in Th1 cells rather than in Th0 or Th2. However, given that uninfected and bystander cells expressed low levels of Th1 cytokines and given previous reports implicating tat in up-regulating the expression of IL-2 and other cytokines,10,29-34 it is likely that HIV is up-regulating the expression of Th1 cytokines. Regardless of whether HIV preferentially infects Th1 or mediates the up-regulation of Th1 cytokines, the presence of productive HIV in predominantly Th1 cells may, over time, lead to the depletion of this subpopulation. However, our study evaluating the rate of apoptosis of HIV productively infected cells indicated that apoptosis was marginally enhanced in productively infected cells in comparison with uninfected or bystander cells. This finding is consistent with recent reports26,35 indicating lack of apoptosis in infected cells on the basis of HIV reporter constructs to discriminate between infected and bystander cells, using multiple apoptosis assays. This relatively low level of apoptosis in HIV productively infected cells correlated with potent up-regulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl2. The mechanism of both IL-2 and Bcl-2 up-regulation was shown to be phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase sensitive, indicating a possible role for common γ-chain signaling. However, since Wortmanin did not completely abrogate IL-2 and Bcl-2 up-regulation, additional signaling pathways may also be involved. IL-2, in turn, is shown to be at higher levels among productively infected cells. Evolutionarily, antiapoptosis mechanisms are favorable for virus propagation. Up-regulating IL-2 and Bcl-2 in infected cells is consistent with this concept. Both tat and nef have been implicated in up-regulating Bcl-2.36,37

HIV productively infected cells also enter the cell cycle at a higher frequency than bystander or uninfected cells, yet these cells do not complete cell division, as evaluated by CFSE staining, and are arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle, as evaluated by both PI and pyronin/7AAD costaining. HIV viral protein R (Vpr) has been well established to mediate this G2/M cell cycle arrest.38 Unlike previous reports linking Vpr to G2/M arrest and apoptosis,39,40 our research did not show a link between this cell cycle arrest and an enhanced rate of apoptosis in infected cells.40 Those previous reports relied heavily on transfecting Vpr alone whereas our study was based on whole virus infection. As we reported, infection may lead to IL-2 up-regulation, which has been linked to the conferring of protection of infected cells against apoptosis.41-43

HIV productively infected cells were also more activated, as measured by fatty acid synthase (Fas) receptor (CD95) and CD25 (α-chain of IL-2 receptor) cell surface expression. The higher level of cell activation correlated with up-regulation of the HIV coreceptors CXCR4 and CCR5. While CXCR4 is predominant on unstimulated/resting CD4+ T cells, its expression is up-regulated with cell activation.44 CCR5 expression, on the other hand, is lower on unstimulated/resting cells and is dramatically increased in response to cell activation.44-46 These findings are consistent with up-regulation of activation markers on the HIV productively infected subpopulation. Additionally, this finding is consistent with the well-documented concept that HIV-1 replicates more efficiently in activated cells, given that cell activation may produce factors essential for virus gene expression and subsequently replication. Hyperimmune activation, rather than direct cytopathic effects of the virus, is likely to be responsible for much of the dysregulation associated with HIV/AIDS.47,48

Although we have classified HIV-infected p24- cells as bystander cells that are not productively infected, these cells may indeed have been infected by HIV but either do not actively replicate the virus or have become p24-. Nonetheless, these cells behaved very similarly to mock-infected cells for most parameters examined, suggesting that even if HIV entered these cells, it did not alter their biologic properties.

The virus used in these studies was a laboratory-adapted T-tropic HIV (IIIB) strain. While this virus is CXCR4-specific and contains a mutation that interferes with the expression of the second exon of Tat, dynamics of cytokine expression similar to that in bystander and HIV productively infected cells were observed when 2 primary isolates of HIV (302 151 and 302 144) were used in these studies. This finding indicates that the mutations specific to HIV IIIB were not relevant to the dynamics observed in cytokine expression on infected cells. Also, the data presented here were based on various analyses performed 6 days after infection. Similar trends for cytokines, CD25, CD95, and Bcl-2 in the percentage of HIV+/p24+ expression as compared with uninfected cells were observed at a second time point (13 days after infection; data not shown). Because it was difficult to discriminate between necrotic and apoptotic cells at 13 days after infection, we also evaluated apoptosis in bystander and productively infected cells at days 3 and 6 after infection. Although the percentage of p24 expression was low at 3 days after infection, we still observed similar trends in the apoptosis profiles of infected and bystander cells (data not shown). These observations, substantiated at 2 different time points, indicate that the trends reported and observed in the dynamics of HIV infection are real.

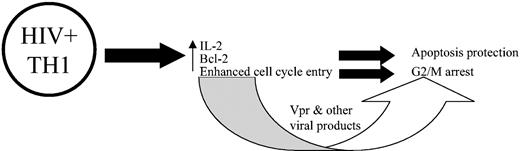

On the basis of the cytokine expression, activation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation data, we propose a model that examines the impact of HIV productive infection on these parameters, as depicted in Figure 8. HIV either specifically targets Th1 cells or up-regulates Th1 cytokine expression; conjointly, the cells become more activated. IL-2 expression leads to up-regulation of Bcl-2, which, in turn, protects the productively infected cells from apoptosis and induces the cells to enter the cell cycle, but these cells are arrested in G2/M stage of the cell cycle because of specific viral proteins.

Proposed model of association between productive HIV replication in CD4+ T cells and cytokine expression, activation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. According to this model, HIV either preferentially infects or up-regulates Th1 cytokines. The presence of type 1 cytokines, such as IL-2, leads to the up-regulation of Bcl-2, which protects the cells from apoptosis and promotes cell cycle entry. However, owing due to viral proteins, as is well documented, the productively infected cells become arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle.

Proposed model of association between productive HIV replication in CD4+ T cells and cytokine expression, activation, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. According to this model, HIV either preferentially infects or up-regulates Th1 cytokines. The presence of type 1 cytokines, such as IL-2, leads to the up-regulation of Bcl-2, which protects the cells from apoptosis and promotes cell cycle entry. However, owing due to viral proteins, as is well documented, the productively infected cells become arrested in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, February 5, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4172.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Cantet Christelle for performing statistical analysis. The following reagents were obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH: human recombinant IL-2 from Dr Maurice Gately, Hoffmann-LaRoche and human T-cell leukemia virus III B/H9 (HTLV IIIB/H9) from Dr Robert Gallo.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal