Abstract

Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is often associated with extramedullary infiltration by leukemic cells at diagnosis or at relapse. To understand the mechanisms behind the dissemination of T-cell ALL (T-ALL) cells this study investigated the homing receptor expression on the blast cells of 11 pediatric T-ALL patients at diagnosis. One patient revealed a unique profile with high expression of the chemokine receptor CCR9 and the integrin CD103 on the T-ALL cells. Both of these molecules are specifically associated with homing to the gut. This finding was clinically significant as the patient later suffered a relapse that was confined to the gut. Immunohistochemistry revealed that the leukemic cells in the gut still expressed CCR9 and colocalized with a high expression of the CCR9 ligand, CCL25. These findings suggest that the original expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the leukemic cells contributed to the relapse location in the gut of this patient. (Blood. 2004;103:2806-2808)

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common childhood malignancy with the potential to infiltrate extramedullary sites.1,2 The homing of such malignant cells to specific sites appears to be a directed rather than a random event.3-6 Tumor cell migration and spread are critically regulated by chemokines and their receptors.7-10 By the preferential chemokine expression in particular sites, they direct the specific homing of hematopoietic cells. Thus the expression of chemokine receptors by malignant cells provides a marker that may predict the tropism of these cells for particular destinations.

We report the case of a 4-year-old child who at diagnosis presented with a T-cell ALL (T-ALL) that subsequently switched to a clonally related acute myeloid leukemia (AML) during treatment. The relapse of leukemia was confined to the gut. Interestingly the leukemic cells of this patient displayed at diagnosis a high level of the gut homing molecules chemokine receptor 9 (CCR9) and CD103. This rare finding is highly suggestive of a role for this receptor in determining the location where the relapse occurred.

Study design

Patients

Peripheral blood and bone marrow samples of 11 children with T-ALL, including the index case 7125, and 1 patient with acute myeloid leukemia (AML, M5) were obtained from the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (The Hague, the Netherlands). Leukemia diagnosis was based on evaluation according to the French-American-British (FAB) criteria.

Flow cytometry

Chemokine receptor antibodies (CCR1-9, CXC receptors 1-6 [CXCR1-6]) were all from R&D Systems (Abingdon, United Kingdom) except CCR4, CCR7, and CXCR3, which were from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA), and CCR8 from Alexis (San Diego, CA). The cutaneous lymphocyte-associated antigen (CLA) and CD103 antibodies were from BD Pharmingen and Immunotech (Marseille, France), respectively. Unlabeled antibodies were visualized using appropriate fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat antimouse or rabbit antigoat isotypes. For triple staining, peridinin chlorophyll-alpha protein/cyanin 5.5-labeled CD3 (BD PharMingen) and/or phycoerythrin-labeled CD7 (Coulter, Westbrook, ME) were used as appropriate. Isotype-matched antibody controls (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) were used to define detection thresholds. Events were collected using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA) and analyzed using CELL QUEST software (BD Biosciences).

Calcium mobilization

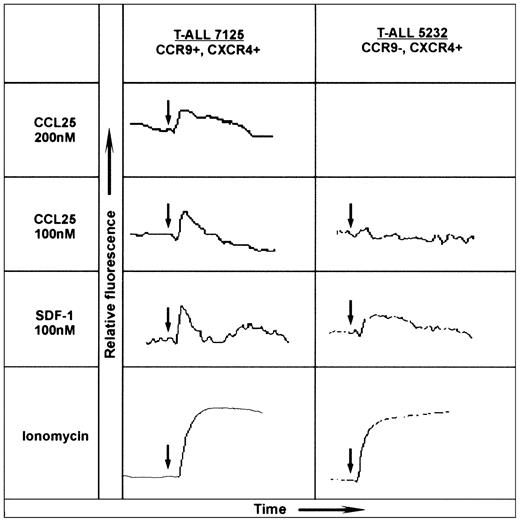

Chemokine receptor activation was assessed by real-time measurement of intracellular Ca2+ changes using Fluo-3 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes, Leiden, the Netherlands) and monitored using a Perkin Elmer spectrometer LS 50B (Warrington, United Kingdom). Chemokines were used as indicated in Figure 2. Ionomycin was used as a positive control.

CCL25/TECK-induced calcium mobilization on CCR9+ T-ALL blasts. The human chemokines CCL25/TECK (CCR9 ligand) and CXCL12/SDF-1α (CXCR4 ligand) were tested for calcium mobilization on 2-mL aliquots of 107/mL Fluo-3 AM-loaded T-ALL blasts. The left panel shows the dose-response of patient 7125 T-ALL blasts to human CCL25/TECK (hCCL25/TECK) and the response to hCXCL12/SDF-1α; the right panel shows the response of patient 5232 to these chemokines. The chemokine receptor expression is indicated at the top of each panel. Ionomycin was also used as a stimulator of calcium influx to obtain the maximal response. The arrows indicate the time of additions.

CCL25/TECK-induced calcium mobilization on CCR9+ T-ALL blasts. The human chemokines CCL25/TECK (CCR9 ligand) and CXCL12/SDF-1α (CXCR4 ligand) were tested for calcium mobilization on 2-mL aliquots of 107/mL Fluo-3 AM-loaded T-ALL blasts. The left panel shows the dose-response of patient 7125 T-ALL blasts to human CCL25/TECK (hCCL25/TECK) and the response to hCXCL12/SDF-1α; the right panel shows the response of patient 5232 to these chemokines. The chemokine receptor expression is indicated at the top of each panel. Ionomycin was also used as a stimulator of calcium influx to obtain the maximal response. The arrows indicate the time of additions.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections of 4 μm taken from the ileum of the patient with CCR9-positive T-ALL at relapse (UPN 7125) were pretreated as described before11 and stained using goat antihuman CCR9 antibody (Capralogics, Hardwick, MA), mouse antihuman CCR ligand 25 (CCL25)/thymus-expressed chemokine (TECK) antibody (R&D Systems), or an isotype-matched antibody (DAKO, Cambridge, United Kingdom). Immunostaining was performed using either StreptABComplex/horseradish peroxidase (HRP; DAKO) and diaminobenzidine (DAB) or EnVision/HRP (DAKO) and VECTOR NovaRed (VECTOR Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Results and discussion

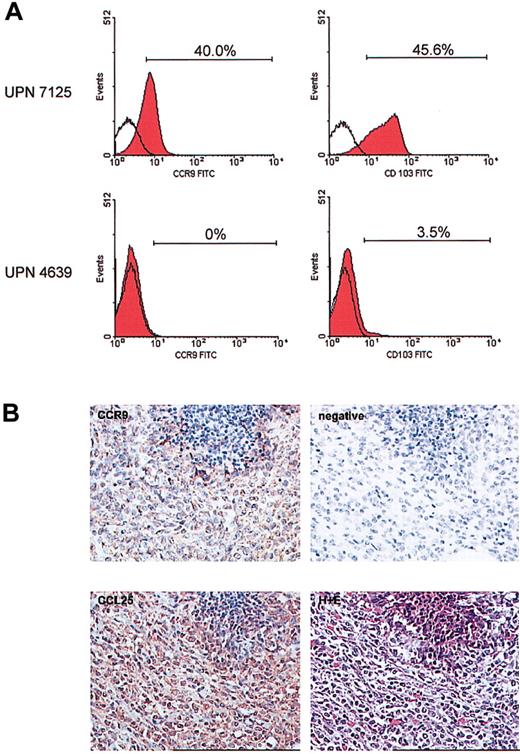

Flow cytometric analysis using a panel of chemokine receptors and other homing molecules (eg, CLA and CD103) was performed on peripheral blood blast cells from 11 T-ALL patients at diagnosis. For 10 of these patients, expression of chemokine receptors on the blast cells did not differ significantly from that seen on T cells of healthy age-matched controls (data not shown). However, the T-ALL cells from 1 patient (UPN 7125) displayed a unique expression profile. The gut homing molecules, CCR9 and CD103 (α4β7), were expressed highly by at least 40% of the T-ALL cells (Figure 1A). The expression of these 2 receptors was extremely low on the T cells from the other 10 T-ALL patients (Figure 1A) and healthy controls (data not shown). This unique homing receptor profile on the leukemic cells at diagnosis correlated with the rare clinical presentation of a gut relapse in patient 7125, 18 months later. None of the other patients studied suffered a similar relapse. It seems that the level of CCR9 expression on these childhood T-ALL cases may be lower than that found in a recent publication.12 This could be explained by the fact that Qiuping et al12 focus on CD4+ T cells, and of course the age of the patients may also affect these results.

Unique expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the leukemic cells of patient 7125. Multicolor flow cytometry was carried out on a peripheral blood sample obtained at diagnosis using a panel of chemokine receptor- and homing molecule-specific antibodies in combination with markers for T cells. (A) The unique expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the blast cells from patient 7125 is shown (top panel). The bottom panel shows a representative result for expression of these same receptors as found on T cells of 10 other T-ALL patients. Open histograms indicate level of control staining; red histograms, specific staining. Brackets and percentages denote the fraction of antibody-positive cells. (B) Immunohistochemistry was performed on the tumor cell infiltrate in the ileum of patient 7125. Using an anti-CCR9 polyclonal antibody and DAB detection (brown) there was clear positivity of the tumor cells for CCR9. The specificity of the CCR9 staining was confirmed by omitting the CCR9 antibody as a negative control. Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining using an anti-CCL25/TECK monoclonal antibody and NovaRed detection revealed a high expression of this CCR9 ligand in the tumor mass. The lower right picture shows hematoxylin and eosin (H+E) staining of the same area of the affected ileum at relapse. Original magnification, × 250.

Unique expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the leukemic cells of patient 7125. Multicolor flow cytometry was carried out on a peripheral blood sample obtained at diagnosis using a panel of chemokine receptor- and homing molecule-specific antibodies in combination with markers for T cells. (A) The unique expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the blast cells from patient 7125 is shown (top panel). The bottom panel shows a representative result for expression of these same receptors as found on T cells of 10 other T-ALL patients. Open histograms indicate level of control staining; red histograms, specific staining. Brackets and percentages denote the fraction of antibody-positive cells. (B) Immunohistochemistry was performed on the tumor cell infiltrate in the ileum of patient 7125. Using an anti-CCR9 polyclonal antibody and DAB detection (brown) there was clear positivity of the tumor cells for CCR9. The specificity of the CCR9 staining was confirmed by omitting the CCR9 antibody as a negative control. Furthermore, immunohistochemical staining using an anti-CCL25/TECK monoclonal antibody and NovaRed detection revealed a high expression of this CCR9 ligand in the tumor mass. The lower right picture shows hematoxylin and eosin (H+E) staining of the same area of the affected ileum at relapse. Original magnification, × 250.

The clinical course of patient 7125 was further uniquely defined by a lineage switch (confirmed by sequencing of clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangements) to an AML at relapse. Immunohistochemistry showed that the AML cells in the gut still expressed the CCR9 receptor (Figure 1B). High expression of the corresponding ligand, CCL25/TECK, was also detected (Figure 1B). This colocalization suggests that the leukemic cells may have contributed to the increased local expression of CCL25. The localized presence of CCL25 at relapse may not just have functioned as a retention factor for the CCR9+ leukemic cells but may also have contributed to leukemic cell growth and survival.13-15

The T-ALL blasts from patient 7125 obtained at diagnosis were tested for their response to CCL25/TECK by monitoring changes in intracellular Ca2+. The addition of 200 and 100 nM CCL25/TECK to the blast cells of patient 7125 resulted in a significant dose-dependent response (Figure 2). CXC ligand 12 (CXCL12)/stromal-derived factor 1α (SDF-1α) whose receptor, CXCR4, was also highly expressed by the T-ALL blasts induced a significant calcium flux as well. Figure 2 further shows representative results from 1 of 3 CCR9-T-ALL patients. These CCR9-, CXCR4+ T-ALL blasts consistently failed to respond to CCL25/TECK, but did respond to CXCL12/SDF-1α.

This study reports the finding of a unique homing receptor profile on the T-ALL cells of a pediatric patient, suggesting that they home to the gut. This result seems particularly relevant as this patient suffered a gut relapse 18 months after diagnosis. These findings are highly suggestive that the expression of CCR9 and CD103 on the original leukemic cells contributed to the relapse location. Based on preliminary results of an ongoing, separate study into AML patients, CCR9 is frequently expressed on AML blasts (M4 and M5), but CD103 expression is rare (N.E.A., unpublished data, November 2003). However, in the case of one AML patient, we did find increased expression of both molecules on the AML blasts at diagnosis. This AML patient was the only one to suffer a gut relapse, supporting our hypothesis regarding the possible role of these receptors in relapse location. The data presented provide further evidence for the link between expression of homing molecules and extramedullary organ infiltration by leukemic cells. If performed at diagnosis, this type of analysis may identify a subset of patients with a high chance of extramedullary relapse.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 4, 2003; DOI 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1812.

Supported financially by “The Quality of Life” fund-raising event. V.H.J.v.d.V. is supported by the Dutch Cancer Foundation/Koningin Wilhelmina Fonds (grant SNWLK 2000-2268).

N.E.A. and A.J.W. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We would like to thank Phary Hart for technical assistance.

Patient material was provided by the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal