Comment on Syrjala et al, page 3386

The longitudinal, neuropsychological assessment study reported by Syrjala and colleagues suggests that long-term cognitive side effects of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation may not be as common as previous research has suggested.

Cancer patients and the providers who care for them are becoming increasingly concerned that cancer treatments may cause long-term cognitive changes that can negatively impact on attainment of educational and work goals and general quality of life. A growing body of literature has suggested that long-term changes in cognitive functioning can be associated with a variety of systemic cancer treatments, including high-dose chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation, standard dose chemotherapy, and biologic response modifiers.1 However, a major problem with this literature is that few longitudinal studies that include pretreatment assessments and long-term follow-up of cognitive functioning have been reported. In the current issue, Syrjala and colleagues report the first large-scale, neuropsychological study that assessed patients undergoing myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) prior to treatment and at 80 days and 1 year after transplantation.

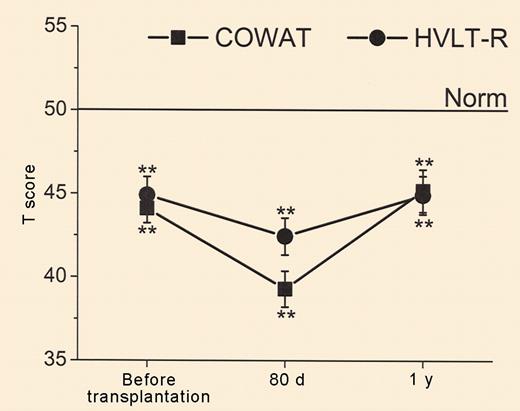

The results of the study demonstrated a significant reduction in performance on all tests of cognitive functioning at the 80-day posttransplantation assessment; however, performance returned to pretransplantation levels at the 1-year assessment on all measures except for grip strength and motor dexterity. Interestingly, a higher percentage of patients than expected scored below published norms prior to transplantation, and performance on tests of verbal fluency and memory were below norms at all 3 testing points. This pattern of results illustrates the critical importance of longitudinal studies. Previous studies that have assessed patients only after treatment have interpreted similar percentages of below normative performance as an indication of the impact of the cancer treatment under study; whereas Syrjala et al were able to demonstrate that similar levels of impairment were, in fact, present before treatment.FIG1

Mean T scores over time for Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised with standard errors. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3386.

Mean T scores over time for Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised with standard errors. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 3386.

Improvement in methodology does not necessarily eliminate all ambiguity from the interpretation of the results, as the authors recognize. From a patient's point of view, the most positive interpretation would be that HCT causes short-term cognitive changes but not long-term cognitive deficits. However, as the authors discuss, the pretreatment performance on the neuropsychological tests may have been lowered due to psychological distress, medical illness, or medications that could have had sedating or other effects on the central nervous system, and may not have represented a “true” measure of cognitive capabilities. In this scenario, one might have predicted that to conclude that HCT had no adverse effects on cognitive functioning would require 1-year test scores above pretreatment levels. An alternative hypothesis is that only a subgroup, perhaps the minority, of patients is vulnerable to long-term cognitive problems secondary to cancer treatments.2 Therefore, examining groups of patients may mask a pattern of results suggesting that most patients recover to normal levels of cognitive functioning after treatment, whereas a subgroup of patients continues to experience deficits. Data from their study provide some support for this hypothesis: patients who had not received chemotherapy, other than hydroxyurea, prior to HCT and patients not receiving chronic graft-versus-host disease medications at 1 year were at lower risk for cognitive impairment at the 1-year assessment. Genetic, hormonal, and immunologic factors may also be important in determining vulnerability to cognitive changes associated with cancer treatments.3 The study reported by Syrjala and colleagues represents a significant advancement in understanding cognitive changes associated with HCT and is a model for future research in this area.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal