Two parallel trials reported in this issue of Blood suggest that intensified CHOP is superior to standard CHOP in the management of histologically aggressive NHL. These studies also suggest that different strategies for dose intensification may be optimal in different patient subgroups.

Ever since the introduction of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) combination chemotherapy for the treatment of histologically aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL),1 attempts have been made to further improve the results by intensifying the therapy administered. Previous escalated regimens have been largely disappointing when tested in large randomized trials, as exemplified by the National High-Priority Lymphoma Study, in which m-BACOD (methotrexate, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone), MACOP-B (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, bleomycin), and Pro-MACE Cyta-BOM (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, prednisone, cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate) were shown to be no better than CHOP.2 This might indicate that intensification of CHOP is of no value, but alternatively it may be that the so-called escalated regimens were not significantly more intensive than the original CHOP regimen. As more drugs were added to the CHOP regimen and/or dosing intervals were reduced, it became necessary to reduce the dose of some agents and it is possible that these reductions were made in the most efficacious drugs. The calculations of relative dose intensity (RDI; according to the method of Hryniuk and colleagues3 ) are confounded by the lack of large or randomized single-agent trials, so the assignment of the relative efficacies of individual components of a regimen is, at best, approximate.FIG1

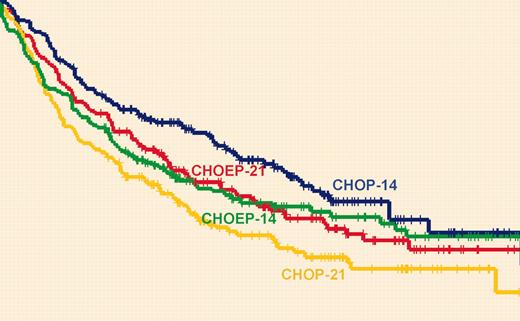

Overall survival in the NHL-B2 trial. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 634.

Overall survival in the NHL-B2 trial. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 634.

Hasenclever and colleagues,4 building on the Skipper et al5 model, have proposed the concept of the effective dose approach, which takes into account not only the total dose of chemotherapy and RDI but also the heterogeneity of histologically aggressive NHL with respect to chemosensitivity and tumor growth rate. They hypothesize that in rapidly growing lymphomas (identified at presentation by the surrogate marker of a raised lactic dehydrogenase [LDH] level), tumor regrowth between cycles is a potential problem and the way forward is to increase the dose intensity by shortening the interval between cycles whilst maintaining the same dose per cycle. This is now achievable with the use of granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF). In patients with a low LDH level, by contrast, the optimal approach may be to keep the intervals the same and increase dose intensity either by increasing the dose of one or more agents or by adding in an additional efficacious agent without reducing the doses of the original drugs.

In this issue of Blood, Pfreundschuh and colleagues report on the prospective testing of this model in 2 large trials with the same 2 × 2 factorial design investigating whether shortening the intervals and/or adding etoposide could improve event-free survival (EFS).

In the NHL-B2 trial for patients older than 60 years (40% of whom had a raised LDH level), an interaction between the 2 randomizations prevented the intended analysis. However, considering the 4 arms separately, the EFS and overall survival (OS) were significantly longer with the dose intensification achieved with CHOP-14 (CHOP given every 2 weeks) compared with the other 3 regimens. Rather surprisingly, CHOP-14 given with G-CSF was not much more toxic than CHOP-21 (CHOP given every 3 weeks), but it should be noted that only 14% of patients had an age-adjusted International Prognostic Index (IPI) score of 2, and 5.2% had a score of 3, which is considerably lower than in most other series and trials of patients of 60 years or older. Some caution must still be exercised, therefore, in the extrapolation of the safety results to a less-selected elderly population.

In the NHL-B1 trial, for good-risk (normal LDH level) adult patients of 60 years of age or younger, the addition of etoposide, but not interval reduction, led to a significant improvement in EFS. The results of the standard CHOP-21 arm in this trial appear rather poor (EFS at 5 years of 54.7%), bearing in mind that all patients had low or low-intermediate IPI risk, but nearly 28% did have bulky disease, which might influence the results.

These results and those of the NHL-B2 trial provide support for the effective dose model, although it is disconcerting that in the NHL-B1 trial, the improvement in EFS with etoposide did not lead to an improvement in OS; in fact there was a significant improvement in OS with interval reduction, as in the trial for older patients.

The authors of these papers conclude that they have defined new “preferred therapies” for histologically aggressive NHL, but the standard therapy today (although not when these trials were started) is not CHOP-21, it is CHOP-21 plus rituximab. Although rituximab may add further to the benefits of CHOP-14 or CHOEP-21 (CHOP plus etoposide), it is possible that the use of rituximab may negate any benefits due to dose intensification. In the rituximab era, it remains unclear whether “more is better,” and further trials are required.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal