Comment on Musaji et al, page 2102

A new study examines how platelets, antiplatelet antibodies, and infection interact clinically to manifest as acute childhood ITP.

Viral infections often predate the onset of childhood or acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), and thus they are presumed to play an essential role in the pathogenesis of this autoimmune syndrome.1 Findings of virus-specific antibodies with cross-reactivity to platelet antigens2,3 have advanced the notion of molecular mimicry as an instigating stimulus for childhood ITP. However, a variety of infectious agents are associated with disease onset in this syndrome,1 and it is not known how such a diverse repertoire of infections can lead to shared immune responses to platelets. In this issue, Musaji and colleagues provide intriguing data to suggest that viral infections may not be involved in the etiology of the autoimmune response per se but rather contribute to disease pathogenesis through enhancement of host phagocyte function.

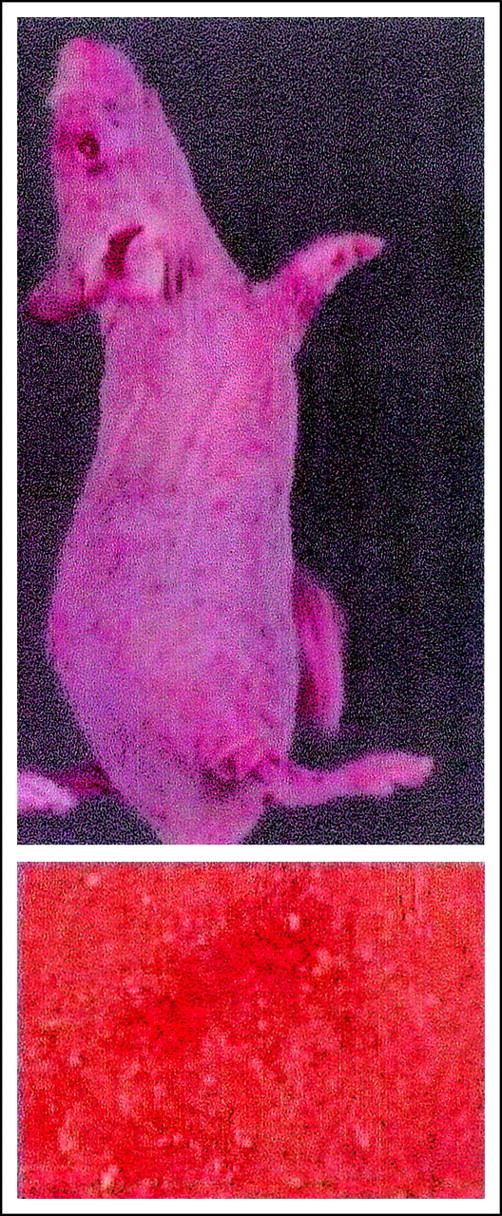

Using in vivo models, the authors demonstrate that mice infected with murine viruses alone or injected only with antiplatelet antibodies experience a moderate thrombocytopenia. However, when mice are subjected to both treatments (viral infection and antiplatelet antibodies), they develop profound thrombocytopenia within 2 to 4 days of infection, with clinical manifestations of purpura. Through additional studies, the authors demonstrate that infection exacerbates the effects of antiplatelet antibodies through interferon-γ (IFN-γ)–mediated up-regulation of phagocyte function. The authors also show that autoimmune thrombocytopenia in the setting of viral infection appears to be self-limited and does not require T-cell collaboration.

The demonstration that viruses enhance reticuloendothelial function or that phagocytic activity mediates clearance of antibody-coated platelets is hardly surprising. What is novel about this study is the experimental observation of the synergizing effects of both phenomena. The findings that mildly asymptomatic antiplatelet antibodies may produce symptomatic disease in the face of viral infection have clinical implications not only for childhood ITP but also for chronic ITP and other infection-associated thrombocytopenic disorders.

With respect to childhood ITP, the authors speculate that disease onset may occur in 2 distinctive phases: a subclinical phase in which children develop clinically inapparent platelet autoantibodies, and a thrombocytopenic phase in which enhanced phagocytic responses are triggered by viral infection. While this proposed model of disease induction may not apply to all cases of childhood ITP, especially in cases where cross-reactive viral/platelet antibodies can be demonstrated, it is a plausible explanation for the 20% to 25% of pediatric patients who appear to manifest an autoimmune-like illness.4 For patients with adult or chronic ITP, the findings in this report also offer an explanation for profound disease exacerbations that often accompany bacterial or viral infections.5 Lastly, this study provides some room for speculation on the mechanisms of infection-associated thrombocytopenia in otherwise healthy hosts. While bacterial andFIG1 viral infections can elicit thrombocytopenia in a number of ways, one potential mechanism may involve unmasking of naturally occurring antiplatelet antibodies.6 Further refinements of this experimental model will allow, perhaps, for defining the causative role of natural and pathogenic antiplatelet antibodies not only with infection but also in other inflammatory conditions associated with thrombocytopenia.

Thrombocytopenic purpura induced by LDV infection in nude mice. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2102.

Thrombocytopenic purpura induced by LDV infection in nude mice. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2102.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal