Comment on Guralnik et al, page 2263

This seemingly simple study is in fact quite provocative because it argues that the usually mild anemia, frequently ignored, that occurs in about 10% of subjects older than 65 years may have serious clinical consequences.

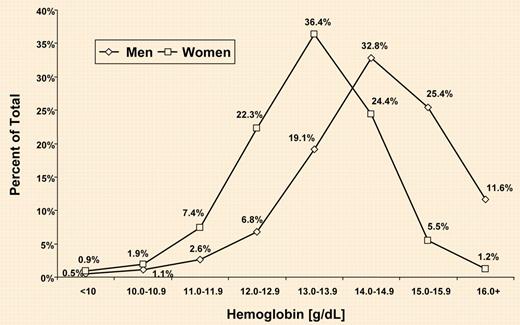

The thrust of the article by Guralnik and colleagues is that anemia, as defined by World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, is very common in those older than 65 years; it is mostly mild anemia, but it should not be considered to be a normal event in the aging process and may have important pathophysiologic consequences. The data are provided by the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). The importance of this survey is that it obtained hemoglobin levels on representative subjects living in the community, of whom almost 4200 were older than 65 years. And of this group, 2096 subjects had further tests to characterize the anemia. The WHO criteria for anemia in adult men is a hemoglobin (hgb) level less than 130 g/L (13 g/dL) and for adult women a hgb level less than 120 g/L (12 g/dL). Using these WHO criteria, the prevalence of anemia in men older than 65 years is 11% and for women it is 10.2%. But this apparent similarity in prevalence rates is dependent on the cut point used because 32.5% of women older than 65 years have hgb levels less than 130 g/L (13 g/dL). While it makes sense during childbearing years to consider sex-different normal hgb levels, is that still the case for those older than 65 years? Of equal interest is the striking ethnic difference, with 3 times as many non-Hispanic blacks of either sex older than 65 years having anemia. It is not clear at this time whether this is a consequence of comorbidities, has a deleterious clinical impact, or is a normal ethnic difference. The anemia in this aging population is usually not severe, with only 2% to 3% of subjects having hgb levels less than 110 g/L (11 g/dL), and as such is frequently ignored. Reference is made to a population-based study of elderly subjects with hgb levels less than 110 g/L (11g/dL) where the diagnosis of anemia was listed in only a quarter of their medical records. The key question then is whether this seemingly casual acceptance of mild anemia in the elderly has a clinical consequence. The authors argue that anemia is not a normal consequence of aging and that even these mild levels of anemia indeed have an impact on morbidity and mortality. They cite literature showing that even very mild anemia impairs physical performance and leads to adverse outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure. The survey also comprised studies designed to identify the cause of the anemia in the aged, although absolute reticulocyte counts, erythropoietin levels, and blood smears were not part of the analysis. The most frequent causes of the anemia were iron deficiency, chronic renal failure, and ACI (anemia of chronic inflammation; formerly ACD). Many of the subjects were also vitamin B12 and folate deficient, although it is not clear that the level of these nutritional deficiencies was sufficient to contribute to the cause of the anemia. A substantial number of cases were classified as unexplained anemia (UA), which lead the authors to wonder if there was an entity of anemia in the aged, perhaps related to defective hypoxia sensing. Further studies are needed to determine if correction of the mild anemia perhaps using erythropoietin will improve the outlook of affected patients. ▪FIG1

Distribution of hemoglobin in persons 65 years and older according to sex. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2263.

Distribution of hemoglobin in persons 65 years and older according to sex. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2263.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal