Abstract

Increasing evidence suggests that autoantibodies directly contribute to hypercoagulability in the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). One proposed mechanism is the antibody-induced expression of tissue factor (TF) by blood monocytes. Dilazep, an antiplatelet agent, is an adenosine uptake inhibitor known to block induction of monocyte TF expression by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. In the current study we characterized the effects of immunoglobulin G (IgG) from patients with APS on monocyte TF activity and investigated whether dilazep is capable of blocking this effect. IgG from 13 of 16 patients with APS significantly increased monocyte TF activity, whereas normal IgG had no effect. Time-course experiments demonstrated that APS IgG-induced monocyte TF mRNA levels were maximal at 2 hours and TF activity on the cell surface was maximal at 6 hours. Dilazep inhibited antibody-induced monocyte TF activity in a dose-dependent fashion but had no effect on TF mRNA expression. The effect of dilazep was blocked by theophylline, a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist. In conclusion, IgG from certain patients with APS induce monocyte TF activity. Dilazep inhibits the increased expression of monocyte TF activity at a posttranscriptional level, probably by way of its effect as an adenosine uptake inhibitor. Pharmacologic agents that block monocyte TF activity may be a novel therapeutic approach in APS.

Introduction

It is widely hypothesized that autoantibodies directly contribute to hypercoagulability in patients with the antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), and numerous pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed. Once such mechanism is the antibody-induced expression of tissue factor (TF; CD142) on monocytes or vascular endothelial cells, or both.1

TF is an integral membrane protein constitutively expressed in many cell types outside of the vasculature, but it is not normally expressed on cells that are in contact with flowing blood. It is a specific and high-affinity receptor for factor VII/VIIa and functions as a cofactor for factor VIIa enzymatic activity. Exposure of active TF to blood triggers physiologic blood coagulation and thrombosis in a wide variety of thrombotic diseases.2 Blood monocytes do not constitutively express functional TF; however, they are capable of TF synthesis and expression when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or certain inflammatory cytokines.3 Expression of TF on monocytes has been implicated as a mechanism of thrombosis in several conditions, including sepsis,4 atherosclerosis,5 the use of oral contraceptives,6 cancer,7 and hyperhomocysteinemia.8 There is growing evidence that certain types of antiphospholipid antibodies, particularly those directed against β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI), stimulate monocyte tissue factor expression in patients with APS.9,10

Current treatment for the prevention of recurrent thrombosis in patients with APS is a high level of anticoagulation with warfarin. The identification of specific mechanisms of hypercoagulability in APS may allow for more specific and targeted therapy. Pharmacologic inhibition of monocyte TF expression is one such approach. Dilazep dihydrochloride, an adenosine uptake inhibitor, is an antiplatelet agent used in Europe and Japan. Interestingly, dilazep has been reported to inhibit endothelial cell and monocyte TF expression induced by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), thrombin, and phorbol ester.11

In the current study, we characterized the effects of immunoglobulin G (IgG) from patients with APS on monocyte TF expression and activity, and we investigated whether dilazep is capable of inhibiting autoantibody-induced TF activity.

Patients, materials, and methods

Patients and antibodies

Serum samples were obtained from 16 patients with APS as defined by the Sapporo consensus criteria for definite APS12 and having medium-to-high serum concentrations of IgG autoantibodies to β2GPI detected by enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), as previously described.13 Each subject gave written informed consent. Total serum IgG was purified from serum by using ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by affinity chromatography with the use of HiTrap Protein G columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden), according to the manufacturer's instructions. IgG F(ab′)2 fragments were obtained by pepsin digestion, and Fc fragments were removed by protein A-Sepharose 4B-CL affinity chromatography.14 Purity of IgG fractions and F(ab′)2 fragments was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Anti-β2GPI antibody activity of purified IgG and F(ab′)2 was confirmed by ELISA. Antibody preparations were free of endotoxin contamination (< 0.03 EU/mL) by Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Associates of Cape Cod, Falmouth, MA). Total IgG was also prepared from 6 healthy control subjects, none of whom had anti-β2GPI.

Purification of β2GPI

Frozen human plasma (5 U) was thawed at 37° C, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 was slowly added to a final concentration of 8%. The mixture was stirred for 45 minutes at 4° C and centrifuged at 6000g for 30 minutes. PEG 8000 was added to the supernatant to a final concentration of 22%, again stirred for 45 minutes at 4° C, and centrifuged at 6000g for 30 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM benzamidine, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). This preparation was chromatographed on S-Sepharose, and proteins were eluted with a gradient from 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.8, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM benzamidine to 25 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.3, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM benzamidine. Fractions containing β2GPI were identified by ELISA (described in “β2GPI ELISA”), pooled, and dialyzed into 5 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane)–HCl, pH 7.4. The dialyzed sample was chromatographed on Heparin-Sepharose CL-6B, and protein was eluted with a gradient from 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, to 400 mM NaCl, 5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. β2GPI-containing fractions were pooled and dialyzed into 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM CaCl2. This solution was chromatographed on calmodulin-Sepharose 4B, and protein was eluted with a gradient from 10 to 500 mM NaCl in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. Finally, β2GPI-containing fractions were pooled, dialyzed into 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 130 mM NaCl, and passed through a protein A-Sepharose CL-4B column. The effluent was collected, concentrated by dialysis against 20 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl (HBS) containing 10% PEG, dialyzed into HBS, divided into aliquots, and stored at –80° C. The purification was monitored by SDS-PAGE and β2GPI ELISA. The identity of β2GPI was confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI MS) fingerprinting and MALDI tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI MS/MS) peptide sequencing.

β2GPI ELISA

β2GPI was quantitated by an indirect competitive ELISA. Microtiter plates (Nunc Maxisorp, Nalge Nune, Rochester, NY) were coated with 0.5 μg/mL β2GPI in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight at 4° C, washed with PBS, blocked for 1 hour with PBS/1% bovine serum albumin/0.05% Tween 20, and washed with PBS. Standards, 10 μg/mL to 20 ng/mL β2GPI, and test samples were diluted in blocking buffer, mixed with an equal volume of 0.3 μg/mL RP-1, a murine anti–human β2GPI monoclonal antibody,15 in blocking buffer, and applied to the plate in duplicate at 50 μL/well. Plates were incubated 2 hours, and wells were subsequently washed with PBS. Bound RP-1 was quantitated by using alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG (Zymed Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA), 1:1000 in blocking buffer, and P-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (Sigma, St Louis, MO). Plates were read and data analyzed, using an Emax microplate reader and SOFTmax Pro software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Affinity purification of anti-β2GPI from APS patient IgG

β2GPI (10 mg) was coupled to a 1-mL HiTrap NHS-activated HP Sepharose column according the manufacturer's instructions (Amerhsam Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). The β2GPI-Sepharose column was equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, and 20 mg APS patient IgG was applied to the column. After collection of the effluent (anti-β2GPI–depleted IgG), the column was washed, and anti-β2GPI antibodies were eluted by using 0.1 M glycine, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 2.8. Fractions (200 μL) were collected into tubes containing 12 μL 1 M Tris, pH 8.0. Peak fractions were pooled, concentrated, and dialyzed into 20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. By ELISA, the anti-β2GPI activity of the affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies was approximately 100-fold more concentrated than that of the total IgG; anti-β2GPI activity of the anti-β2GPI–depleted IgG was undetectable up to a concentration of 250 μg/mL.

Isolation of normal peripheral blood monocytes

Venous blood from healthy individuals was collected in sterile tubes containing 0.129 M sodium citrate (1/9, vol/vol). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by gradient centrifugation by using Accu-Prep (Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY). The cells were washed twice, resuspended in Macrophage SFM medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY), and incubated in 96-well tissue culture plates, 5 × 104 cells/well, at 37° C in 5% CO2. Monocytes were allowed to adhere for 1 hour, and nonadherent cells were removed by washing 3 times with medium.

Assay for monocyte TF activity

TF activity on monocytes was measured as factor VIIa-dependent activation of factor X, using a modification of the method described by Hoffman et al.16 Monocytes, 5 × 104 cells/well, prepared as described in “Isolation of normal peripheral blood monocytes,” were incubated for 6 hours at 37° C in Macrophage SFM medium containing patient or control IgG and/or other agonists and inhibitors. Unless otherwise specified the final concentration of human IgG was 250 μg/mL. Antihuman β2GPI monoclonal antibody (mAb) RP-1 and MOPC-21, an isotype-matched control antibody, were used at a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. Bacterial LPS (Sigma), 500 ng/mL, was used as a positive control. Polymyxin B, 100 U/mL, was included in all assays other than the LPS-positive control. Human β2GPI at a final concentration of 100 μg/mL was added to all assays, unless otherwise specified. Dilazep and/or theophylline (Sigma) were included in certain experiments at the concentrations indicated. After 6 hours cells were washed twice with HEPES-buffered saline (20 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5; HBS) containing 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Factor VIIa (generously provided by Dr D. M. Monroe, Department of Medicine, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill), at a final concentration of 100 pM, and factor X (Haematologic Technologies, Essex Junction, VT), at a final concentration of 135 nM, were then added to the cells. Following incubation at 37° C for 30 minutes, 25-μL aliquots were removed and added to 50 μL HBS containing 5 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and 0.1% BSA. Factor Xa concentration was determined by measuring the rate of cleavage of a chromogenic substrate, Spectrozyme FXa (American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT). Color development was monitored by the absorbance at 405 nm by using a kinetic microplate reader (SpectraMAX 250 and SOFTmax PRO software; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The concentration of factor Xa was calculated from Vmax (mOD/min) using a standard curve. All experiments were performed in duplicate. The viability of the cells at the conclusion of the assay, assessed by trypan blue exclusion, was more than 95%.

Quantitation of TF mRNA by real time RT-PCR (TaqMan PCR)

Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was used to design TF primer sets optimized for TaqMan quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Of 3 primer sets synthesized, one met requirements of specificity, low background, and linearity of response by using SYBR Green I dye detection. The forward primer was TCAGTGATCCACCCACCTT; the reverse primer was GCACCCAATTTCCTTCCATTT. Monocytes were isolated, cultured, and treated as described in the monocyte TF activity assay. Total RNA was isolated by using RNA Stat-60 (Tel-Test). Quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR assays were performed in triplicate on an Applied Biosystems 7700 Real Time Quantitative PCR system by using a TaqMan EZ RT-PCR Kit. Human cyclophilin was used as the control housekeeping gene. Standard RT extension, PCR annealing, and amplification temperatures were used, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA (50 ng) was used in each reaction. The relative level of TF mRNA was determined using standard 2(–ΔΔCT) calculations.

Statistical analysis

Data shown as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of duplicate determinations were calculated by using GraphPad Prism 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

APS IgGs increase monocyte TF expression and activity

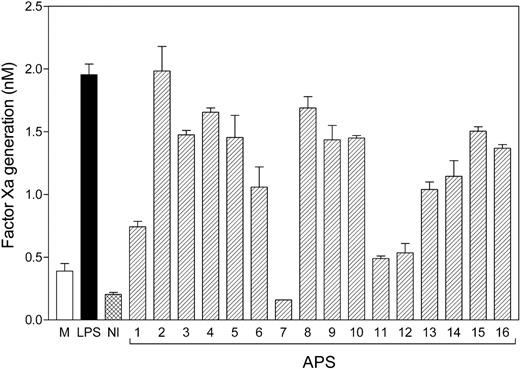

As shown in Figure 1, certain APS patient IgGs significantly increased monocyte TF activity, as compared with control normal IgG. IgGs from 16 patients with APS were analyzed, and 13 (81%) increased TF activity above that observed with media alone or normal IgG. Factor Xa generation was undetectable when factor VIIa was omitted from the assay, indicating that factor Xa generation was TF mediated (data not shown).

Purified IgG from some APS patient sera increases TF activity on normal monocytes. Monocytes from healthy individuals were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from 16 patients with APS (▨), IgG from a healthy individual (Nl, ▩), LPS (500 ng/mL, ▪), or media alone (M, □) in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). After 6 hours, cells were washed and assayed for TF activity as described. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

Purified IgG from some APS patient sera increases TF activity on normal monocytes. Monocytes from healthy individuals were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from 16 patients with APS (▨), IgG from a healthy individual (Nl, ▩), LPS (500 ng/mL, ▪), or media alone (M, □) in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). After 6 hours, cells were washed and assayed for TF activity as described. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

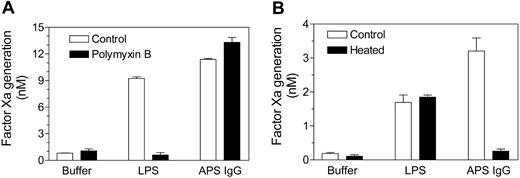

To assure that APS IgG-induced TF activity was not due to endotoxin contamination, 2 additional experiments were performed (Figure 2). First, as demonstrated in Figure 2A, the addition of polymyxin B (100 U/mL) inhibited induction of monocyte TF activity by LPS but had no effect on APS IgG-induced TF activity. Second, as shown in Figure 2B, LPS and APS IgG were each heated to 100° C for 10 minutes, allowed to cool, and then added to the monocyte cultures. Heating, which denatures IgG, inhibited the effect of APS IgG but had no effect on LPS-induced TF expression. These data strongly suggest that antibody-induced TF activity is not due to contamination with bacterial endotoxin. Note that the absolute amount of factor Xa generation varies among assays, for example, the differences in y-axis scaling between Figures 2A and B. In our experience, this variability is due to differences between healthy donor monocytes.17 The relative differences because of agonists (antibodies, LPS) and antagonists demonstrated in the current study were independent of donor monocyte variability.

Enhancement of monocyte TF activity by APS IgG is not due to contamination with endotoxin (LPS). (A) Polymyxin B (100 U/mL) inhibits monocyte TF activity induced by LPS (500 ng/mL) but not by an APS patient IgG (500 μg/mL). (B) Heating to 100° C for 10 minutes destroys the ability of APS IgG to stimulate monocyte TF activity but has no effect on LPS. Assays of APS IgG were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

Enhancement of monocyte TF activity by APS IgG is not due to contamination with endotoxin (LPS). (A) Polymyxin B (100 U/mL) inhibits monocyte TF activity induced by LPS (500 ng/mL) but not by an APS patient IgG (500 μg/mL). (B) Heating to 100° C for 10 minutes destroys the ability of APS IgG to stimulate monocyte TF activity but has no effect on LPS. Assays of APS IgG were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

Time course and dose response of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity

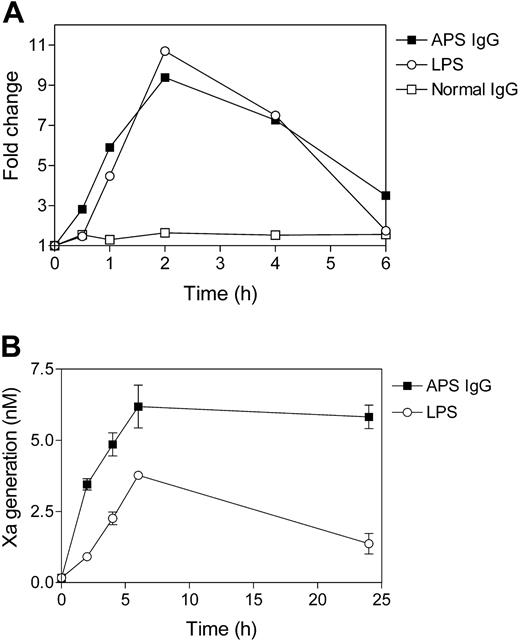

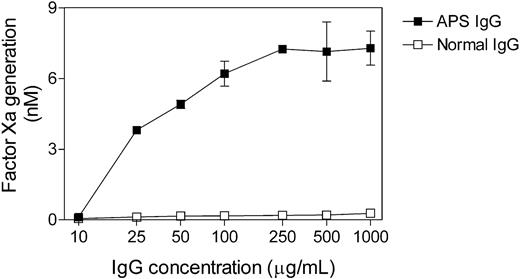

The time course analysis of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF mRNA expression and enzymatic activity is shown in Figure 3. TF mRNA expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 3A, stimulation with either APS IgG or LPS resulted in a 9- to 11-fold increase in TF mRNA level that was maximal at 2 hours. TF enzymatic activity, in contrast, was maximal at 6 hours (Figure 3B), 4 hours following the mRNA peak. The dose response of TF activity to APS IgG is shown in Figure 4. TF activity reached a maximal at an IgG concentration of 250 μg/mL, with no further increase at up to a 4-fold higher IgG concentration.

Time course of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF mRNA expression and enzymatic activity. (A) TF mRNA expression in monocytes was measured by real-time RT-PCR (TaqMan). Normal monocytes were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from a patient with APS or a healthy individual, in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). Stimulation with LPS (500 ng/mL) was performed as a positive control. Fold change is relative to the expression level at time zero. Data shown are the mean of triplicate determinations. (B) TF activity on monocytes was measured as factor VIIa-dependent activation of factor X. Normal monocytes were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from a patient with APS or a healthy individual, in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL), and TF activity was measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

Time course of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF mRNA expression and enzymatic activity. (A) TF mRNA expression in monocytes was measured by real-time RT-PCR (TaqMan). Normal monocytes were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from a patient with APS or a healthy individual, in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL). Stimulation with LPS (500 ng/mL) was performed as a positive control. Fold change is relative to the expression level at time zero. Data shown are the mean of triplicate determinations. (B) TF activity on monocytes was measured as factor VIIa-dependent activation of factor X. Normal monocytes were incubated with IgG (250 μg/mL) from a patient with APS or a healthy individual, in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL), and TF activity was measured at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 24 hours. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations.

Dose dependence of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were incubated with varying concentrations of APS IgG or normal IgG for 6 hours in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Scaling of the x-axis, IgG concentration, is logarithmic. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 2 experiments.

Dose dependence of APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were incubated with varying concentrations of APS IgG or normal IgG for 6 hours in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Scaling of the x-axis, IgG concentration, is logarithmic. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of 2 experiments.

Anti-β2GPI monoclonal antibody RP-1 and affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies induce increased monocyte TF activity

All patient IgGs selected for this study had moderate to high concentrations of anti-β2GPI antibodies. To investigate whether anti-β2GPI antibodies are directly implicated in the induction of monocyte TF activity, we first studied the effect of RP-1, a murine monoclonal antibody specific for human β2GPI, in the monocyte TF assay. In the presence of exogenous β2GPI, RP-1 (50 μg/mL) induced TF activity as compared with isotype control antibody MOPC-21 (1.45 ± 0.31 versus 0.48 ± 0.01 nM factor Xa generated). In the absence of exogenous β2GPI, RP-1 caused a small increase in TF activity compared with MOPC-21 (0.39 ± 0.06 versus 0.14 ± 0.02 nM factor Xa generated), perhaps because of a small amount of endogenous β2GPI adherent to the monocytes. To determine whether patient-derived anti-β2GPI antibodies induced monocyte TF activity, anti-β2GPI antibodies were affinity-purified from the IgG of a patient with APS. The effects of total IgG and anti-β2GPI–depleted IgG, both tested at 250 μg/mL, were compared with affinity-purified anti-β2GPI IgG, 25 μg/mL. Total IgG generated was 1.08 ± 0.07 nM factor Xa in contrast to 0.45 ± 0.07 nM factor Xa induced by anti-β2GPI–depleted IgG and 1.71 ± 0.14 nM factor Xa induced by affinity-purified anti-β2GPI IgG.

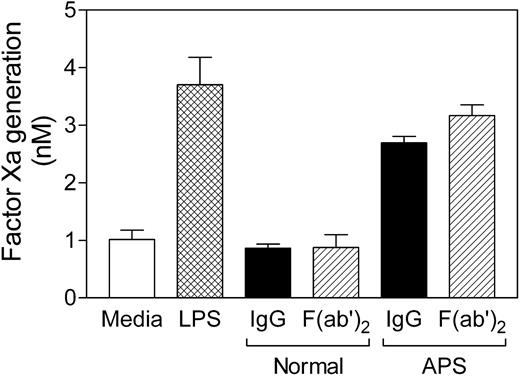

APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity is not Fc-mediated

To investigate whether APS IgG-induced TF activity is mediated by the Fc portion of the antibodies by way of Fcγ-receptors, F(ab′)2 fragments were prepared by pepsin digestion. As shown in Figure 5, the F(ab′)2 fragment of APS IgG had the same effect as the intact IgG molecule. These data suggest that Fc and Fcγ-receptors are not involved in mediating antibody-induced monocyte TF activity.

F(ab′)2 fragments of APS IgG increase monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were incubated for 6 hours with APS or normal IgG (250 μg/mL, ▪) or equimolar concentrations of the corresponding F(ab′)2 fragments (▨), and β2GPI (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Controls were media alone (□) and LPS (500 ng/mL, ▩). Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations.

F(ab′)2 fragments of APS IgG increase monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were incubated for 6 hours with APS or normal IgG (250 μg/mL, ▪) or equimolar concentrations of the corresponding F(ab′)2 fragments (▨), and β2GPI (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Controls were media alone (□) and LPS (500 ng/mL, ▩). Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations.

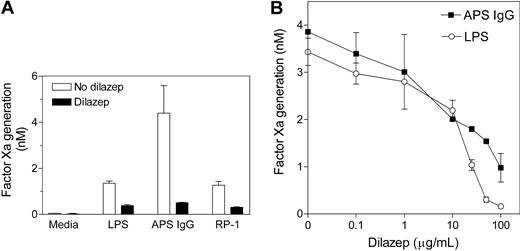

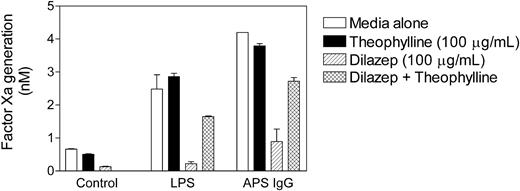

Dilazep inhibits APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity

The use of pharmacologic agents to inhibit monocyte TF expression is a potentially novel approach to the treatment of hypercoagulability in APS. Dilazep is an adenosine uptake inhibitor known to block the induction of monocyte TF expression by LPS.11 Therefore, we examined whether dilazep could also inhibit APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. As shown in Figure 6A, dilazep, 100 μg/mL, inhibited TF activity induced by LPS by 74%, APS IgG by 89%, and anti-β2GPI mAb RP-1 by 78%. Dilazep itself did not affect the measurement of factor Xa generation in our assays. Figure 6B demonstrates that dilazep inhibited the effects of LPS and APS IgG in a dose-dependent manner. The IC50 (concentration that inhibits 50%) of dilazep was approximately 13 μg/mL for APS IgG and approximately 16 μg/mL for LPS. In data not shown, dilazep did not inhibit monocyte TF mRNA synthesis induced by APS IgG or LPS, suggesting that the drug inhibits TF expression at a posttranscriptional level. To initially investigate whether dilazep was acting by way of its effect on adenosine transport, we examined the effect of theophylline, a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist. Figure 7 demonstrates that theophylline itself did not stimulate monocyte TF activity and had no significant effect on LPS- or APS-induced TF activity. Theophylline partially counteracted the inhibitory effect of dilazep, restoring 54% of dilazep-inhibited LPS-induced TF activity and 63% of dilazep-inhibited APS IgG-induced TF activity. These data, although preliminary, suggest that dilazep may act by increasing the extracellular concentration of adenosine and thereby stimulating one or more monocyte adenosine receptors.

Dilazep inhibits APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. (A) Normal monocytes were stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL), APS IgG (250 μg/mL), or RP-1 (50 μ/mL) in the presence or absence of dilazep (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. (B) Normal monocytes were stimulated with LPS or APS IgG in the presence of varying concentrations of dilazep, washed, and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. Assays of APS IgG and RP-1 were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL).

Dilazep inhibits APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. (A) Normal monocytes were stimulated with LPS (500 ng/mL), APS IgG (250 μg/mL), or RP-1 (50 μ/mL) in the presence or absence of dilazep (100 μg/mL), washed, and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. (B) Normal monocytes were stimulated with LPS or APS IgG in the presence of varying concentrations of dilazep, washed, and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. Assays of APS IgG and RP-1 were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL).

Theophylline blocks the effect of dilazep on APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were stimulated with APS IgG (250 μg/mL), LPS (500 ng/mL), or unstimulated (control) in the presence of dilazep (100 μg/mL), theophylline (100 μg/mL), or both dilazep and theophylline. Cells were then washed and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. Assays of APS IgG were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL).

Theophylline blocks the effect of dilazep on APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. Normal monocytes were stimulated with APS IgG (250 μg/mL), LPS (500 ng/mL), or unstimulated (control) in the presence of dilazep (100 μg/mL), theophylline (100 μg/mL), or both dilazep and theophylline. Cells were then washed and assayed for TF activity. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of duplicate determinations. Assays of APS IgG were performed in the presence of β2GPI (100 μg/mL).

Discussion

In the first part of the current study, our data demonstrate that IgG fractions from certain patients with APS induced TF expression and activity on normal blood monocytes. The effect of APS IgG was dose dependent, was not due to endotoxin contamination, and was Fc independent. Time course experiments showed that antibody-induced TF mRNA expression peaked at 2 hours, and TF activity on the cell surface peaked at 6 hours. The magnitude of TF expression and activity was roughly comparable to that induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. A murine monoclonal antibody to human β2GPI, RP-1, and affinity-purified anti-β2GPI antibodies from a patient with APS also induced monocyte TF activity, suggesting that certain antibodies to β2GPI are capable of inducing TF. It is not clear why IgGs from most of the patients stimulated monocyte TF expression and activity, whereas antibodies from a few patients did not. Concentrations of anti-β2GPI antibodies were comparable between the 2 groups. Differences in the epitope specificity of anti-β2GPI autoantibodies may explain this observation.

The possible role of monocyte TF activity in APS was first suggested by de Prost et al18 who observed that monocyte procoagulant activity was increased in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, about half of whom had lupus anticoagulants. Subsequently, several groups have reported that serum, plasma, purified total IgG, and anti-β2GPI antibodies from patients with APS enhance TF expression and procoagulant activity on normal monocytes.9,10,19-21 Cuadrado et al22 and Dobado-Berrios et al23 reported that ex vivo monocytes from patients with APS had increased expression of TF and of TF mRNA. Our data further characterize and quantify this phenomenon and provide the background necessary to begin to investigate pharmacologic agents that may block monocyte TF activity.

In the second part of this study, we examined the effects of the drug dilazep dihydrochloride on APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity. Dilazep, an antiplatelet agent, is reported to inhibit in vitro monocyte and endothelial cell TF expression induced by several stimuli, including TNF-α, thrombin, and phorbol ester.11 In vivo, dilazep decreased plasma concentrations of soluble TF, D-dimer, thrombin-antithrombin complexes, and fibrinogen in patients with a hypercoagulable state associated with malignancy.11 Mechanistically, dilazep is an adenosine uptake inhibitor that acts by increasing extracellular adenosine levels, and adenosine has been shown to be an inhibitor of TF expression.24,25 Our data demonstrate that dilazep inhibited APS IgG-induced monocyte TF activity in a dose-dependent fashion. The inhibition was partially blocked by theophylline, a nonspecific adenosine receptor antagonist, suggesting that dilazep is active by way of its effect on adenosine transport. Future studies with specific adenosine receptor antagonists will better define dilazep's mechanism of action.

Theoretically, inhibition of monocyte TF expression is an attractive approach to the prevention of thrombosis in APS and other hypercoagulable conditions. The side effects of such treatment would likely have less risk of bleeding complications than long-term anticoagulation with warfarin (the current treatment for prevention of recurrent thrombosis in APS). In addition to dilazep, several other drugs have been shown to inhibit increased expression of TF on monocytes and endothelial cells induced by LPS and other stimuli. Dipyridamole is an antiplatelet agent and adenosine uptake inhibitor similar to dilazep. Pentoxifylline, a methylxanthine with hemorheologic effects, has been shown to inhibit monocyte TF expression induced by LPS.26,27 Several angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors (captopril, imidapril, and fosinopril) significantly inhibit LPS-induced monocyte TF activity, antigen expression, and gene transcription.28,29 Finally, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (simvastatin, fluvastatin) reduce TF activity, antigen expression, and gene transcription.30-32 Interestingly, fluvastatin has recently been shown to inhibit thrombosis in a murine model of APS.33

Direct evidence that inhibition of TF can prevent thrombosis is provided by studies of active-site inactivated factor VIIa (FVIIai). FVIIai is a modified form of recombinant factor VIIa in which the enzymatic active site has been blocked by a synthetic inhibitor.34 Importantly, FVIIai binds to TF with higher affinity than factor VIIa but lacks procoagulant activity.34 FVIIai has been shown to have a potent antithrombotic effect in 2 animal models of arterial thrombosis.35,36

In summary, our data suggest that autoantibody-induced monocyte TF expression may be an important mechanism of hypercoagulability in patients with APS and, therefore, a potential target of therapy. Pharmacologic agents that block monocyte TF activity, such as dilazep, are a novel therapeutic approach in APS and worthy of further study.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 29, 2004; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0145.

Supported by an American Heart Association Established Investigator Grant (R.R.) and a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (grant HL69545).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Dougald M. Monroe III for his many thoughtful consultations and Melody Shaw for her expert technical assistance.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal