Comment on Selleri et al, page 2198

Selleri et al demonstrate that healthy donors given granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) have increases in plasma soluble plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) levels, which in turn induces chemotaxis of CD34 cells. Selleri et al's findings help better define the complicated mechanism of stem cell mobilization by G-CSF and point to a wide role for uPAR in cell surface adhesion and recognition.

G-CSF, stem cell factor (SCF), and high-dose cyclophosphamide increase peripheral blood CD34 counts in stem cell donors prior to leukapheresis. Nevertheless, 14% of patients receiving G-CSF for the purpose of autologous donation and 4% for allogeneic donors fail to mobilize.1 Most of what we know about stem cell mobilization is derived from animal models. Adhesion molecules such as VLA-4 and P/E selectins, chemokines, their cognate ligands (stromal derived growth factor 1 [SDF-1] and CXCR4), and proteolytic enzymes such as elastase and cathepsin G all appear to play a part in facilitating mobilization and homing of hematopoietic stem cells.

Membrane-associated uPAR is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored (GPI)–anchored protein, first identified as a high-affinity cellular receptor for the inactive proenzyme prourokinase plasminogen activator (uPA);2 uPAR is believed to increase generation of plasmin, either by increasing the catalytic activity of uPA or by facilitating juxtaposition of this enzyme with membrane-associated plasminogen. The uPAR is composed of 3 domains, the first required for generation of plasmin and the third attached to the cell membrane by a GPI anchor. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor is expressed as a differentiation antigen on cells of the myelomonocytic lineage and as an activation antigen on monocytes, T lymphocytes, and probably platelets. In addition to its role in plasminogen activation, uPAR appears to mediate cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix adhesion.3 Some evidence suggests that paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuia (PNH) neutrophils, lacking GPI-anchored protein, are deficient in chemotactic activity,4 a feature that has been attributed to the absence of uPAR.FIG1

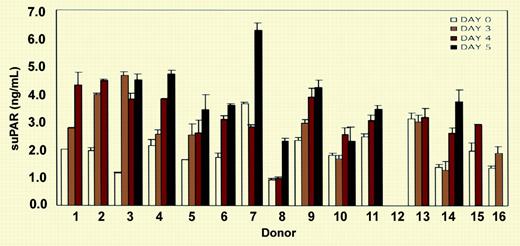

ELISA measurement of soluble uPAR (suPAR) in the sera of 15 donors. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2198.

ELISA measurement of soluble uPAR (suPAR) in the sera of 15 donors. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 2198.

When uPAR is cleaved at the GPI anchor by endogenous phospholipase D, soluble uPAR (suPAR) is released from the cell membrane.5 Plasma levels of suPAR are increased in metastatic carcinoma where it has been used to monitor disease activity.6 Plasma levels are also increased in PNH patients who lack the GPI-anchored proteins in affected hematopoietic clones. In this study, Selleri et al demonstrate that suPAR is released in vitro after G-CSF treatment and attribute this to membrane shedding of up-regulated membrane uPAR on immature granulocytes and monocytes, although these cells also have substantial pools of intracellular suPAR.2 They go on to show that soluble uPAR induces chemotaxsis of CD34 cells and down-regulates CXCR4, a chemokine receptor important in retaining stem cells in the bone marrow.

Although the authors speculate that suPAR has therapeutic potential in patients failing to mobilize following G-CSF treatment, suPAR has been reported to antagonize fibrinolysis in vitro,7 and the potential toxicities of suPAR need to be clarified. Nevertheless, even if suPAR turns out to have no clinical application, it may yet provide a tool for the study of hematopoietic stem cell mobilization and homing. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal