Dendritic cells (DCs) play an important role in initiating and maintaining primary immune responses. However, mechanisms involved in the resolution of these responses are elusive. We analyzed the effects of 15d-PGJ2 and the synthetic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ ligand troglitazone (TGZ) on the immunogenicity of human monocyte-derived DCs upon stimulation with toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. Activation of PPAR-γ resulted in a reduced stimulation of DCs via the TLR ligands 2, 3, 4, and 7, characterized by down-regulation of costimulatory and adhesion molecules and reduced secretion of cytokines and chemokines involved in T-lymphocyte activation and recruitment. MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) production was increased due to PPAR-γ activation. Furthermore, TGZ-treated DCs showed a significantly reduced capacity to stimulate T-cell proliferation, emphasizing the inhibitory effect of PPAR-γ activation on TLR-induced DC maturation. Western blot analyses revealed that these inhibitory effects on TLR-induced DC activation were mediated via inhibition of the NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways while not affecting the PI3 kinase/Akt signaling. Our data demonstrate that inhibition of the MAP kinase and NF-κB pathways is critically involved in the regulation of TLR and PPAR-γ-mediated signaling in DCs.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are the most potent antigen-presenting cells and play an important role in initiating and maintaining primary immune responses. They capture antigens in the periphery and migrate to draining lymph nodes, where they present antigenic peptides to T lymphocytes. This may result either in induction or inhibition of antigen-specific immune responses, ensuring protective immunity to infectious agents and tumors while preserving self tolerance.1,2 However, little is known about the termination of immunologic responses once they have been induced. Recently, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) and its ligands have been shown to have potent modulatory effects on B and T lymphocytes as well as DCs.3-6 Prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) and its metabolite 15-deoxy-Δ PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) as well as other cyclopentenone prostaglandins are produced during the late phase of inflammation due to up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), a key enzyme for the synthesis of cyclopentenone prostaglandins, that mediate their effects by activation of PPAR-γ-dependent and -independent pathways. Synthetic PPAR-γ ligands include a class of antidiabetic drugs, the thiazolidinediones (TZDs).

Innate immune responses mediated by toll-like receptors (TLRs) are the first line of defense against infectious agents entering the organism. Until now, 11 members of the TLR family have been reported in mammalians,7-11 each recognizing distinct pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).12 The diversity of PAMPs being recognized by TLRs is further increased by heterodimerization between certain TLRs.13,14 Upon ligand binding, a signal cascade is initiated involving recruitment of different adaptor molecules like myeloid differentiation primary-response protein 88 (MyD88), Interleukin-1R (IL-1R)-associated kinases (IRAKs) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6).15

In our study we show that TLR ligands can mediate different activation signals to human DCs that result in eliciting of distinct functional properties. Furthermore, PPAR-γ activation impairs the immunogenicity of human monocyte-derived DCs upon stimulation with various TLR ligands by inhibition of the MAP kinase and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Dendritic cell generation

DCs were generated from peripheral blood-adhering monocytes by either magnetic cell sorting or plastic adherence as described previously.16 The cells were cultured in RP10 medium (RPMI 1640 with glutamax-I, supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal calf serum [FCS], and antibiotics [Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany]) supplemented with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (100 ng/mL; Leucomax; Novartis, Nuremberg, Germany) and IL-4 (20 ng/mL; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) for 7 days. Cytokines were added to differentiating DCs every 2 to 3 days. 15d-PGJ2 (5 μM; Biomol, Hamburg, Germany) and troglitazone (TGZ, 5 μM; Biomol) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to the culture medium starting from the first day of culture together with GM-CSF and IL-4. To exclude effects induced by the solvent, equal amounts of DMSO were added as a control. On day 6, cells were stimulated by addition of TLR2 ligand (TLR2L) Pam3Cys (5 μg/mL; EMC microcollections, Tübingen, Germany), TLR3L Poly(I:C) (50 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany), TLR4L LPS (100 ng/mL; Sigma-Aldrich), or TLR7L R848 (2 μg/mL; InvivoGen, San Diego, CA).

Immunostaining

Cells were stained using fluoresceine isothiocyanate (FITC)-or phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibodies. Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany). A proportion of 1% false positive events was accepted in the negative control samples.

Migration assay

Two × 105 cells were seeded into a transwell chamber (8 μm; BD Falcon, Heidelberg, Germany) in a 24-well plate, and migration to CCL19 (100 μg/mL; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany) was analyzed after 16 hours by counting gated DCs for 60 seconds in a FACSCalibur.

Analysis of endocytic capacity

For the analysis of endocytic activity, 1 × 105 cells were incubated with FITC-dextran (40 000 MW, Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) for 1 hour at 37°C. As a control, 1 × 105 cells were precooled to 4°C prior to the incubation with dextran at 4°C for 1 hour. The cells were washed 4 times and immediately analyzed on a FACSCalibur cytometer.

Cytokine determination

Cytokine concentrations in supernatants from DC cultures were measured with commercially available 2-site sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) from R&D Systems (regulated upon activation, normal T-cell-expressed and presumably secreted [RANTES], MCP-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α [MIP-1α]) and Beckmann Coulter (Hamburg, Germany; IL-12, TNF-α, IL-6) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

One × 105 responding cells from allogeneic peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were cultured in 96-well flat-bottom microtiterplates (Greiner Bio-One GmbH, Frickenhausen, Germany) with varying numbers of stimulator cells. Thymidine incorporation was measured on day 5 by a 16-hour pulse with [3H]thymidine (0.5 μCi [0.0185 MBq]/well; Amersham Life Science, Buckingham, United Kingdom). The assay was performed in 4-fold replicates.

PAGE and Western blotting

Nuclear extracts were prepared from DCs as described previously.17,18 For the preparation of whole-cell lysates, cells were lysed in a buffer containing 1% Igepal, 0.5% sodium-deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 2 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 2 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 mM sodium-orthovanadate. Protein concentrations of protein lysates were determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Pierce, Perbio Science, Bonn, Germany). For the detection of nuclear localized NF-κB family members, approximately 20 μg of nuclear extracts were separated on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany). Ponceau S staining of the membrane was performed to confirm that equal amounts of protein were present in every lane. The blot was probed with a monoclonal antibody against c-Rel (B-6, mouse monoclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). For analysis of the activation state of MAP kinases p38 and ERK and Akt kinase, 20 to 30 μg of whole-cell lysates was separated on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with phospho-specific antibodies phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182, rabbit polyclonal) and phospho-p44/42 (Thr202/Tyr204, mouse monoclonal, all Cell Signaling Technology, New England Biolabs, Frankfurt, Germany). As a control, antibodies against p38 MAP kinase (rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology) and ERK1 (C-16, rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz) were used.

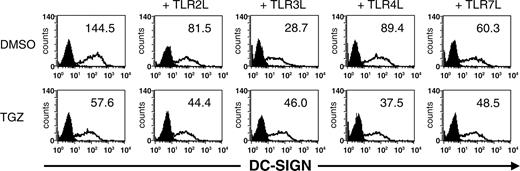

Surface expression of DC-SIGN is decreased upon DC stimulation via TLR. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). The effect of TGZ on DC phenotype was analyzed by flow cytometry. Open histograms represent staining with the indicated antibody; shaded histograms, the isotype control. The surface expression is indicated as mean fluorescence intensity.

Surface expression of DC-SIGN is decreased upon DC stimulation via TLR. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). The effect of TGZ on DC phenotype was analyzed by flow cytometry. Open histograms represent staining with the indicated antibody; shaded histograms, the isotype control. The surface expression is indicated as mean fluorescence intensity.

Statistical analyses

All experiments were performed at least 3 times; representative experiments are presented. To analyze statistical significance, Student t test was used.

Results

PPAR-γ activation in DC inhibits their activation via toll-like receptor signaling

Activation of PPAR-γ by PGD2 and cyclopentenone prostaglandins like 15d-PGJ2 is one possible way to terminate an inflammatory process during the late phase of inflammation.

In this study, we therefore analyzed the possible role of PPAR-γ activation on the immunogenicity of monocyte-derived DCs upon stimulation with various toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands. Expression of TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7 in monocyte-derived DCs treated with synthetic PPAR-γ agonist troglitazone (TGZ) from the first day of culturing was confirmed by semiquantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (data not shown).

Comparison of the phenotypic effects of the various TLR ligands (TLRLs) on DC maturation revealed that the up-regulation of maturation marker and co-stimulatory molecules was most pronounced upon stimulation of the cells with TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, and TLR7L R848. Moreover, the expected down-regulation of CD1a and activation markers like CD83, CD80, or CD40 on the cell surface due to TGZ treatment6 was independent of the TLRL used (data not shown).

Interestingly, a decreased expression of DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intracellular adhesion molecule [ICAM] 3-grabbing nonintegrin) on DCs treated with TLR ligands was observed. The strongest inhibition of DC-SIGN expression on the cell surface was detected upon stimulation with TLR3L. Incubation of DCs with TGZ resulted in a further reduction of DC-SIGN expression except upon TLR3 stimulation (Figure 1).

We next analyzed the secretion of cytokines and chemokines known to be involved in T-lymphocyte activation by DCs generated in the presence of TGZ and TLR ligands. In contrast to TLR2 and TLR7 ligation, activation of DCs by TLR3L Poly(I:C) and TLR4L LPS increased secretion of MIP-1α (CCL3), MCP-1 (CCL2), RANTES (CCL5), IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL12. Interestingly, TLR2L induced only very low amounts of IL-12 (Table 1).

Impact of TGZ on TLR ligand-induced chemokine and cytokine secretion

. | No TLR ligand . | . | + TLR2L . | . | + TLR3L . | . | + TLR4L . | . | + TLR7L . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | |||||

| RANTES (CCL5; pg/mL)* | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | 1.7 | < 1.0 | > 20 000 | 1673 | 6160 | 526 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | |||||

| MIP-1α (CCL3; pg/mL)* | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | 209.5 | 71.0 | 316.0 | 157 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | |||||

| MCP-1 (CCL2; pg/mL)† | 52.5 | 174.6 | 97.5 | 453.9 | 729.9 | 1646.6 | 1004.9 | 1464.8 | 89.2 | 387.4 | |||||

| IL-12 (pg/mL)† | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 23.3 | < 0.1 | > 1000 | 380.5 | > 1000 | 443.6 | 367.5 | < 0.1 | |||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL)† | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 1113.5 | 1469.8 | 1744.7 | 1695.8 | 7.2 | 0 | |||||

| IL-10 (pg/mL)* | 2 | < 1 | 14 | < 1 | 26 | < 1 | 224 | 5 | 5 | < 1 | |||||

. | No TLR ligand . | . | + TLR2L . | . | + TLR3L . | . | + TLR4L . | . | + TLR7L . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | |||||

| RANTES (CCL5; pg/mL)* | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | 1.7 | < 1.0 | > 20 000 | 1673 | 6160 | 526 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | |||||

| MIP-1α (CCL3; pg/mL)* | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | 209.5 | 71.0 | 316.0 | 157 | < 1.0 | < 1.0 | |||||

| MCP-1 (CCL2; pg/mL)† | 52.5 | 174.6 | 97.5 | 453.9 | 729.9 | 1646.6 | 1004.9 | 1464.8 | 89.2 | 387.4 | |||||

| IL-12 (pg/mL)† | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | 23.3 | < 0.1 | > 1000 | 380.5 | > 1000 | 443.6 | 367.5 | < 0.1 | |||||

| IL-6 (pg/mL)† | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 1113.5 | 1469.8 | 1744.7 | 1695.8 | 7.2 | 0 | |||||

| IL-10 (pg/mL)* | 2 | < 1 | 14 | < 1 | 26 | < 1 | 224 | 5 | 5 | < 1 | |||||

Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were incubated for 6 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 with or without 5 μM TGZ starting from the first day of culture. The cells were incubated with different TLR ligands as a maturation stimulus 24 hours before harvesting. Chemokine and cytokine secretion was determined in the supernatant using commercially available ELISAs.

Donor 1

Donor 2

Activation of PPAR-γ during DC development using TGZ had no obvious effect on TNF-α and IL-6 secretion (Table 1, data not shown) while it reduced RANTES, MIP-1α, IL-10, and IL-12 secretion of cells treated with Poly(I:C) and LPS (Table 1). Interestingly, addition of TGZ to developing DCs resulted in an increase in MCP-1 secretion (Table 1) that was demonstrated to inhibit IL-12 secretion and differentiation of DCs.

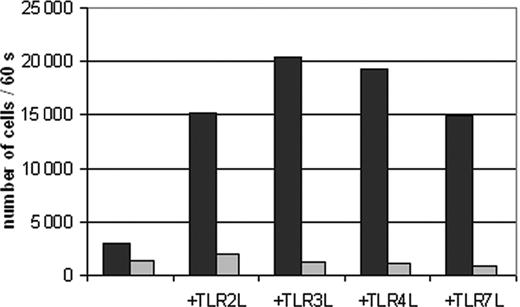

TLR ligand-induced migration of DCs to CCL19 is impaired by PPAR-γ activation. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). The effect of TGZ on DC migration against CCL19 was analyzed using transwell chambers. 2 × 105 DCs were seeded in the upper chamber in triplicates, and the number of migrated DCs was analyzed after 16 hours. ▪ indicates DMSO; ▦, TGZ.

TLR ligand-induced migration of DCs to CCL19 is impaired by PPAR-γ activation. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). The effect of TGZ on DC migration against CCL19 was analyzed using transwell chambers. 2 × 105 DCs were seeded in the upper chamber in triplicates, and the number of migrated DCs was analyzed after 16 hours. ▪ indicates DMSO; ▦, TGZ.

TLR ligand-induced migration of DCs to CCL19 is impaired upon PPAR-γ activation

Recently, it was shown in a mouse model that PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone may affect the migration of Langerhans cells and pulmonary antigen-presenting cells (APCs) to lymph nodes.19 We therefore analyzed whether PPAR-γ activation by TGZ had any effect on the migratory capacity of human monocyte-derived DCs (Figure 2). While immature DCs migrated only marginally, DCs stimulated with TLR ligands showed a high migratory capacity. Addition of TGZ to the cell cultures almost completely blocked the migration of DCs.

TGZ treatment enhances dextran uptake by DCs stimulated with TLR ligands

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analyses and determination of cytokine and chemokine production of DCs treated with TGZ suggested that PPAR-γ activation inhibits TLR ligand-induced maturation of DCs. To test this more functionally, the ability of the cells to endocytose FITC-dextran was analyzed. As shown in Figure 3, FITC-dextran accumulated in immature DCs incubated at 37°C, whereas the control cells incubated at 4°C did not take up the dextran. Treatment of these cells with Pam3Cys, Poly(I:C), and LPS resulted in a reduction of FITC-dextran uptake while the TLR7 ligand R848 had a marginal effect on dextran incorporation, indicating that each TLR ligand may selectively activate or inhibit distinct DC functions. TLR7 stimulation resulted in an intermediate level of IL-12 production as compared to TLR2 (lowest IL-12 secretion) or TLR3 and TLR4 (highest IL-12 production) ligation, while keeping the endocytic ability of immature DCs. In line with a previous report by Szatmari and colleagues,20 incubation of immature DCs with TGZ increased this endocytotic capacity in all DC populations and antagonized the TLR-induced inhibition of dextran uptake.

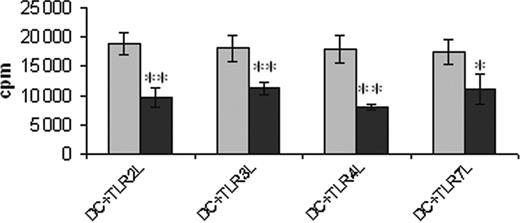

PPAR-γ activation reduces the capacity of TLR ligand-activated DCs to initiate lymphocyte proliferation

The ability of the generated DC populations to stimulate allogeneic T-cell responses was analyzed in a mixed lymphocyte reaction. As shown in Figure 4, TGZ-treated DCs showed a significantly decreased T-cell stimulatory capacity, independent of the maturation stimulus used.

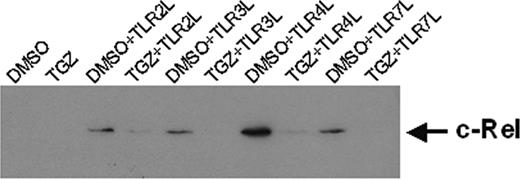

PPAR-γ activation down-regulates nuclear c-Rel

The signal transduction pathway of IL-1R/TLR is mediated by several adaptor molecules. To analyze whether the inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ activation on TLR ligand-induced DC maturation were mediated by the adaptor molecule MyD88, Western blot analyses were performed. However, no effects on the expression level of this protein could be detected (data not shown).

Recently, it was shown that members of the NF-κB family of transcription factors are important for the differentiation and function of DCs.21-25 Therefore, we evaluated the nuclear localization of c-Rel in the generated DC populations. The amount of nuclear c-Rel was reduced in cells treated with TGZ (Figure 5). The effects were even more pronounced when the cells were grown in the presence of 15d-PGJ2 (data not shown). These results suggest that the effects of PPAR-γ activation are mediated at least in part by inhibition of NF-κB signaling pathways.

TGZ treatment enhances dextran uptake by DCs stimulated with TLR ligands. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). One × 105 DCs were incubated with FITC-dextran for 1 hour at 37°C, washed 4 times, and analyzed immediately on a FACSCalibur. As control, cells were precooled to 4°C and incubated with FITC-dextran for 1 hour at 4°C. Open histograms represent FITC-dextran-treated cells incubated at 37°C; shaded histograms, the controls incubated at 4°C.

TGZ treatment enhances dextran uptake by DCs stimulated with TLR ligands. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of TGZ. Different TLR ligands were added to the cells 24 hours before analysis (TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, TLR7L R848). One × 105 DCs were incubated with FITC-dextran for 1 hour at 37°C, washed 4 times, and analyzed immediately on a FACSCalibur. As control, cells were precooled to 4°C and incubated with FITC-dextran for 1 hour at 4°C. Open histograms represent FITC-dextran-treated cells incubated at 37°C; shaded histograms, the controls incubated at 4°C.

In contrast, treatment of DCs with PPAR-γ agonist TGZ did not affect the nuclear expression of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 3 (data not shown), which was shown to be specifically induced by stimulation of TLR3 and TLR4.26

The inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ ligands are mediated via MAP kinase pathway

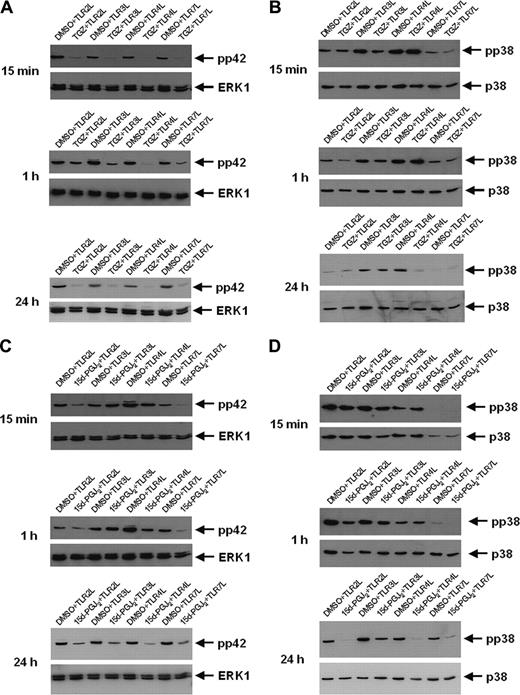

Regulation of NF-κB expression and function involves several pathways, including the MAP and Akt kinases. To examine this, Western blot analyses with phospho-specific antibodies against p38, ERK1, and Akt were used to determine the possible involvement of these pathways in the inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ activation at different time points after stimulation of the cells.

As shown in Figure 6A, a decrease in TLR ligand-induced phosphorylation of ERK1 (pp42) was observed in all cell populations treated with TGZ from 15 minutes up to 24 hours after stimulation. However, TGZ treatment resulted only in the inhibition of TLR4 ligand (LPS)-induced p38 phosphorylation (Figure 6B). In contrast, 15d-PGJ2, the natural ligand of PPAR-γ that can mediate both PPAR-γ-dependent and -independent effects, inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK1 as well as p38 in all analyzed cell populations (Figure 6C, D). However, while reduced phosphorylation of pp42 in 15d-PGJ2-treated DCs was apparent 15 minutes after incubation with TLR2 and TLR7 ligand, the inhibition of TLR3 and TLR4 ligand stimulation was observed after 24 hours. For p38 phosphorylation, distinct inhibitory effects were seen only after 24 hours. In comparison to other TLR ligands, incubation of DCs with TLR7 ligand resulted in the lowest level of p38 phosphorylation (Figure 6B,D). The level of Akt phosphorylation or expression was not influenced by PPAR-γ activation (data not shown). A summary of our results is given in Table 2.

Impact of PPAR-γ activation on TLR ligand-induced DC functions

. | No TLR ligand . | . | + TLR2L . | . | + TLR3L . | . | + TLR4L . | . | + TLR7L . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | |||||

| DC maturation marker | – | – | ++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | |||||

| RANTES, MIP-1α, IL-10, IL-12 | – | – | – (+) | – | +++ | + | +++ | + | – (+) | – | |||||

| MCP-1 | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | |||||

| Dextran uptake | + | ++ | – | ++ | – | ++ | – | ++ | + | ++ | |||||

| Migration | – | – | ++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | ++ | – | |||||

| Nuclear c-Rel | – | – | + | – | + | – | +++ | – | + | – | |||||

| ERK phosphorylation | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | |||||

| p38 phosphorylation | – | – | (+) | (+) | + | + | ++ | – | – | – | |||||

. | No TLR ligand . | . | + TLR2L . | . | + TLR3L . | . | + TLR4L . | . | + TLR7L . | . | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | DMSO . | TGZ . | |||||

| DC maturation marker | – | – | ++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | |||||

| RANTES, MIP-1α, IL-10, IL-12 | – | – | – (+) | – | +++ | + | +++ | + | – (+) | – | |||||

| MCP-1 | + | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | |||||

| Dextran uptake | + | ++ | – | ++ | – | ++ | – | ++ | + | ++ | |||||

| Migration | – | – | ++ | – | +++ | – | +++ | – | ++ | – | |||||

| Nuclear c-Rel | – | – | + | – | + | – | +++ | – | + | – | |||||

| ERK phosphorylation | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | |||||

| p38 phosphorylation | – | – | (+) | (+) | + | + | ++ | – | – | – | |||||

Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were incubated for 6 days in the presence of GM-CSF and IL-4 with or without 5 μM TGZ starting from the first day of culture. The cells were incubated with different TLR ligands as a maturation stimulus 24 hours before harvesting. - indicates negative; +, positive; ++, up-regulated, highly positive; +++, highly up-regulated, very highly positive; and (+), scarcely positive.

Discussion

The termination of once-induced immunologic responses plays a pivotal role in the control of the immune system, but the complex mechanisms involved in the resolution of immunologic responses are still not clear.

Troglitazone treatment reduces the T-cell stimulatory ability of DCs. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of troglitazone from the first day of culture were incubated with TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, and TLR7L R848, respectively, 24 hours before harvesting the cells. Generated DC populations were used to stimulate allogeneic T lymphocytes in a standard MLR. 1 × 104 DCs were used. Error bars indicate standard deviation. **P = .001; *P < .02. ▦ indicates DMSO; ▪, TGZ.

Troglitazone treatment reduces the T-cell stimulatory ability of DCs. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of troglitazone from the first day of culture were incubated with TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, and TLR7L R848, respectively, 24 hours before harvesting the cells. Generated DC populations were used to stimulate allogeneic T lymphocytes in a standard MLR. 1 × 104 DCs were used. Error bars indicate standard deviation. **P = .001; *P < .02. ▦ indicates DMSO; ▪, TGZ.

In our study we show that maturation of DCs induced by various TLR ligands results in activation of distinct effector functions characterized and mediated by different molecular events. The activation of DCs via TLR can be inhibited by PPAR-γ agonists by affecting the NF-κB and MAP kinase pathways, supporting the important role of these mediators in the regulation of inflammatory and immunologic processes.

Cyclopentenone prostaglandins that bind and activate PPAR-γ have recently become the focus of investigation of immune homeostasis.3,4 They are produced during the late phase of inflammation due to up-regulation of COX2 and may have anti-inflammatory properties.27 Moreover, they might inhibit immune responses by inducing apoptosis in T and B lymphocytes and DCs.28 Activation of PPAR-γ by its ligands during inflammation could represent a pathway showing how once-initiated immunologic and inflammatory responses are terminated or inhibited by means of a negative feedback. Naturally occurring PPAR-γ agonists like PGD2 or its derivate, 15d-PGJ2, are synthesized by COX2 that is induced and expressed in the tissues during the late phase of inflammation. The production of these prostaglandins results in activation of PPAR-γ-mediated transcription and leads to the inhibition of the differentiation, migration, and cytokine secretion by antigen-presenting cells like DCs or macrophages. These prostaglandins also can affect the priming and effector functions of T lymphocytes and induce their apoptotic cell death.5,29-31

In our study we show that activation of PPAR-γ by its natural ligand 15d-PGJ2 as well as the synthetic compound troglitazone resulted in a decreased activation of human monocyte-derived DCs by various TLR ligands. Interestingly, the expression of DC-SIGN upon treatment with TLR ligands was decreased, and even more pronounced, by TGZ treatment.4 DC-SIGN is a type II C-type lectin organized in microdomains that is exclusively expressed at the cell surface of DCs. It functions as an adhesion receptor facilitating T-cell binding and priming through recognition of glycosylated intercellular adhesion molecule-3 (ICAM-3) on naive T cells. Furthermore, DC-SIGN serves as an adhesion receptor mediating cellular interactions between DCs and endothelial cells (DC-SIGN/ICAM-2), and also as an antigen receptor that binds and internalizes antigens for processing and presentation in the late endosomal/lysosomal compartments to T cells. DC-SIGN recognizes viruses such as HIV-1, Dengue virus, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and Ebola through high-mannose glycans and can promote their transmission to permissive cells. The binding of other pathogens such as Aspergillus fumigatus conidia, M tuberculosis, Lactobacillus, and H pylori to DC-SIGN does not result in immune activation but enables these pathogens to mediate or elicit the induction of tolerogenic, regulatory, or T helper 2 (Th2)-inducing DCs, which allows them to escape immune surveillance.32,33

Troglitazone down-regulates the expression of nuclear localized c-Rel. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 with or without troglitazone from the first day of culture. For activation of DCs, cells were incubated with different toll-like receptor ligands 24 hours before preparing nuclear extracts. Nuclear localized c-Rel protein was detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Ponceau S staining was performed to ensure equal loading of the gel.

Troglitazone down-regulates the expression of nuclear localized c-Rel. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 with or without troglitazone from the first day of culture. For activation of DCs, cells were incubated with different toll-like receptor ligands 24 hours before preparing nuclear extracts. Nuclear localized c-Rel protein was detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Ponceau S staining was performed to ensure equal loading of the gel.

The inhibitory effects of troglitazone are mediated by MAP kinase. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of troglitazone (A,B) and 15d-PGJ2 (C,D), respectively. Fifteen minutes, 1 hour, and 24 hours before analysis, cells were incubated with TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, and TLR7L R848, respectively. Phosphorylation state of MAP kinase ERK1 (A,C) and p38 (B,D) was analyzed using phosphospecific antibodies.

The inhibitory effects of troglitazone are mediated by MAP kinase. Peripheral blood adhering monocytes were cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in the presence or absence of troglitazone (A,B) and 15d-PGJ2 (C,D), respectively. Fifteen minutes, 1 hour, and 24 hours before analysis, cells were incubated with TLR2L Pam3Cys, TLR3L Poly(I:C), TLR4L LPS, and TLR7L R848, respectively. Phosphorylation state of MAP kinase ERK1 (A,C) and p38 (B,D) was analyzed using phosphospecific antibodies.

Further analyses revealed that secretion of cytokines and chemokines involved in T-cell activation was modified in TLR ligand-stimulated DCs treated with PPAR-γ agonists. Interestingly, addition of various TLR ligands resulted in a distinct maturation status of DCs characterized by diverse cytokine and chemokine production and endocytic capacity. While Pam3Cys and R848 did not induce MIP-1α, RANTES, IL-6, and IL-10 even in control cells, their secretion increased upon stimulation with Poly(I:C) and LPS. Furthermore, stimuli provided by TLR3 and TLR4 ligation mediated higher IL-12 secretion, which was markedly reduced by PPAR-γ activation, demonstrating that different TLR ligands induce a distinct pattern of DC activation.

Our results are in contrast to a recent report by Dillon and colleagues,34 who report that TLR2 ligand binding induces IL-10 secretion favoring Th2 responses, while LPS (TLR4L) activates DCs to secrete IL-12 and only little IL-10 in favor of Th1 responses in mouse splenic DCs, emphasizing that different DC subsets react differentially to TLR ligand-induced activation.

Interestingly, MCP-1 secretion was increased in cells treated with troglitazone. This chemokine was shown to suppress IL-12 secretion by monocytes, macrophages, and monocyte-derived DCs,35,36 thus providing one possible explanation for the reduced IL-12 production observed in our experiments. In line with these results, analyses of the functional properties of the DC populations generated in the presence of TGZ resulted in a significantly decreased ability to stimulate T-cell proliferation in a mixed leukocyte reaction (MLR).

TLR signaling is mediated by several adaptor molecules of the MyD88-adaptor family.37-41 To further analyze which pathways are involved in the inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ activation on TLR ligand-induced DC maturation, we analyzed the expression of the adaptor molecule MyD88. Studies with MyD88-/- mice revealed that this protein is essential for the responses to IL-1, IL-18, and LPS.42,43 Moreover, macrophages of these animals produce no inflammatory cytokines or IL-6 in response to peptidoglycan, lipoprotein, CpG DNA, dsRNA, imidazoquinolines, or flagellin.44-50 However, LPS activates NF-κB, Jnk, or p38 in MyD88-/- macrophages with a time delay,43 indicating that there exists a MyD88-independent pathway. Recently, it was shown that this MyD88-independent signaling by TLR4 is mediated via TRAM (TRIF-related adaptor molecule) and TRIF (Toll/IL1R [TIR] domain containing adaptor molecule).51-53 In our experiments, no effect on MyD88 expression was detected by Western blot analysis, suggesting that the inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ activation on TLR ligand-induced DC maturation is not mediated via MyD88.

The NF-κB transcription factors have been shown to be key regulators of immune responses.54 The signal cascade activating NF-κB is initiated among other stimuli via the recognition of PAMPs by TLR. Once activated, NF-κB can translocate to the nucleus where it then induces the transcription of proinflammatory genes. Moreover, the NF-κB transcription factor family plays a crucial role in the development and function of myeloid DCs,21,55-58 and RelB was shown to be involved in the regulation of DC immunogenicity by PPAR-γ.6 Therefore, we analyzed the effect of TLR ligand-induced activation of DCs treated with TGZ on nuclear localized c-Rel. Analyses with c-Rel-/- mice have shown that this transcription factor regulates the expression of various genes involved in cell division and immune function in B and T cells.58 Moreover, recent reports have demonstrated that c-Rel regulates IL-12 expression in DC59 and is essential for the T-cell stimulatory function of DCs.60 PPAR-γ activation resulted in a pronounced down-regulation of nuclear c-Rel in all cell populations, indicating that c-Rel is involved in the inhibitory effects of TGZ on DC maturation. In contrast, no effect on the expression and nuclear amount of IRF-3, a transcription factor shown to be specifically induced by TLR3 and TLR4,26 was detectable.

In the next set of experiments we evaluated the involvement of the MAP kinases p38 and ERK, proteins located further upstream in the signaling pathway that can mediate NF-κB activation. Previous reports implicated a critical role for MAP kinase in the regulation of Th1/Th2 balance in T cells61 and the regulation of cytokine production by APCs.62 Moreover, it was demonstrated that different TLR agonists have distinct effects on DCs, resulting in diverse Th responses mediated by certain components of the MAP kinase pathway.63 A decrease in phosphorylation of ERK1 (pp42) was observed in all cell populations treated with TGZ. However, phosphorylation of p38 was affected by TGZ treatment only in TLR4 ligand (LPS)-stimulated cells. In contrast, incubation of DCs with 15d-PGJ2, the natural ligand of PPAR-γ, inhibited the phosphorylation of ERK1 as well as p38 in all tested cell populations. In contrast to TGZ, 15d-PGJ2 can mediate both PPAR-γ-dependent and -independent effects,64 which might explain the observed differences.

In summary, our results demonstrate that inhibition of the MAP kinase and NF-κB pathways is critically involved in the regulation of TLR and PPAR-γ-mediated signaling in DCs and represent a novel negative feedback mechanism involved in the resolution of immunologic responses.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, August 16, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4709.

Supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB510).

S.A. and V.M. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Sylvia Stephan, Bruni Schuster, and Tina Hörnle for excellent technical assistance, as well as Markus Manz and Arthur Melms, University of Tübingen, Germany, for critical reading of the manuscript.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal