Abstract

The phosphatidyl-inositol 3 kinase (PI3k)/Akt pathway has been implicated in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). Because rapamycin suppresses the oncogenic processes sustained by PI3k/Akt, we investigated whether rapamycin affects blast survival. We found that rapamycin induces apoptosis of blasts in 56% of the bone marrow samples analyzed. Using the PI3k inhibitor wortmannin, we show that the PI3k/Akt pathway is involved in blast survival. Moreover, rapamycin increased doxorubicin-induced apoptosis even in nonresponder samples. Anthracyclines activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), and disruption of this signaling pathway increases the efficacy of apoptogenic stimuli. Rapamycin inhibited doxorubicin-induced NF-κB in ALL samples. Using a short interfering (si) RNA approach, we demonstrate that FKBP51, a large immunophilin inhibited by rapamycin, is essential for drug-induced NF-κB activation in human leukemia. Furthermore, rapamycin did not increase doxorubicin-induced apoptosis when NF-κB was overexpressed. In conclusion, rapamycin targets 2 pathways that are crucial for cell survival and chemoresistance of malignant lymphoblasts—PI3k/Akt through the mammalian target of rapamycin and NF-κB through FKBP51—suggesting that the drug could be beneficial in the treatment of childhood ALL. (Blood. 2005;106:1400-1406)

Introduction

In recent decades, conventional chemotherapy has produced a dramatic improvement in survival of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (cALL)1 ; however, refractory or relapsed disease remains a problem. Anticancer drug research is aimed at developing new compounds directed against inappropriately activated cell-signaling pathways that stimulate the uncontrolled growth of neoplastic cells.2 A deregulated cytokine circuitry has been proposed in the malignant transformation of lymphoid precursors in primary B- and T-lineage ALL.3 Other reports suggest that the insulin-like growth factor system plays a pathogenetic role in cALL.4,5 Phosphorylation of cytokine6,7 or growth factor receptors4,5 generate docking sites for signaling molecules, thereby activating the phosphatidyl-inositol 3 kinase (PI3k)/Akt-protein kinase B survival pathway,4-7 which promotes blast growth.4,5

The carbocyclic lactone-lactum antibiotic rapamycin, which has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of allograft rejection,8 exerts an anticancer effect by decreasing cell proliferation and increasing apoptosis.9,10 Therefore, rapamycin is expected to suppress cytokine responses11 and tumor-cell survival.12 The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a serine-threonine kinase that regulates protein translation, cell-cycle progression, and cellular proliferation.13-16 In response to growth factors, hormones, mitogens, and amino acids,15-17 mTOR is activated through phosphorylation by Akt18 and in turn activates 2 key translational regulators: the initiation factor 4E binding protein (4E-BPI),16 and p70-kDa S6 ribosomal protein kinase (p70S6k).14 The pathways governed by mTOR and p70S6k are involved in the survival of malignant lymphoblasts,19 which explains the antileukemic activity of rapamycin detected in human cell lines and in a murine model.19 Taken together, these findings prompted us to investigate whether rapamycin induces apoptosis of ALL blasts.

We recently demonstrated that rapamycin sensitized a poorly responsive human melanoma cell line to doxorubicin-induced apoptosis.20 Anthracycline compounds activate nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)/Rel nuclear translocation,21 and disruption of this signaling pathway increases the efficacy of apoptogenic stimuli.22 We showed that the immunophilin FKBP51 is required for IκBα degradation after stimulation with doxorubicin.20 FKBP51, which is specifically inhibited by rapamycin binding,23 exerts peptidyl-prolyl-isomerase activity that catalyzes the isomerization of peptidyl-prolyl-imide bonds in subunit α of the IKK kinase complex, and is required for IKK function.24 Given the foregoing, we investigated whether rapamycin inhibits anthracycline-induced NF-κB/Rel activity in blasts from cALL, and increases sensitivity to chemotherapy.

Finally, to assess the role of FKBP51 in NF-κB/Rel activation in lymphoid cells, we down-modulated FKBP51 levels in the Jurkat leukemic cell line using a short interfering (si) RNA approach, and investigated whether IκBα degradation and NF-κB/Rel nuclear translocation occurred in the absence of the IKKα cofactor.

Patients, materials, and methods

Cells and culture conditions

Bone marrow samples were obtained between April 2002 and October 2004 from 15 children affected by B-ALL and from 10 children affected by T-ALL (Table 1). Twenty-two samples were collected at diagnosis, 2 at relapse (patients 18 and 22), and 1 from a patient who partially responded to therapy (patient 8). It is declared that informed consent was provided by the patients' parents in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for these studies, conducted in the departments of Biochemistry and Medical Biotechnologies, University of Naples Federico II (Naples, Italy); Pediatric Onco-Hematology, AORN Pausilipon (Naples, Italy); and Clinical and Experimental Medicine, “Magna Graecia” University (Catanzaro, Italy).

Patient profiles

Patient no. . | Sex . | Age, y.mo . | %Blasts . | Lineage . | WBC count, 109/L . | Immunophenotype . | Genetic rearrangement . | GR* . | RR† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 11.3 | 100 | B | 111.680 | CD10, CD19, CD34 | T(12;21) | Good | Yes |

| 2 | M | 6.11 | 100 | T | 15.760 | CD10, CD7, CD2, CD3cy, CD4, CD8 | — | Good | Yes |

| 3 | M | 2.10 | 84 | T | 118.740 | CD7, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD2, CD3+/− | — | Good | Yes |

| 4 | F | 11.10 | 100 | T | 198.510 | CD7, CD34, CD3cy, CD2, CD5, TdT | Partial deletion chromosome 1 | Poor | No |

| 5 | M | 14.5 | 100 | B | 40.600 | CD10, CD34, CD19, DR, CD33, CD13 | — | Good | No |

| 6 | M | 13.10 | 95 | B | 56.130 | CD19, CD79a-cy CD22, CD24, DR, | — | Good | Yes |

| 7 | M | 3.3 | 100 | B | 5.790 | CD10, CD19, CD24, TdT, CD34, CD38 | NT | Good | No |

| 8 | M | 9.4 | 20 | T | 3.650 | CD5, CD7, CD3cy, CD1a | — | Poor | Yes |

| 9 | M | 3.9 | 90 | B | 98.100 | CD34, CD19, CD10, DR, CD13, CD33, TdT | t(9;22) | Poor | No |

| 10 | M | 7.4 | 100 | T | 314.950 | CD3cy, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD7, CD5, TdT | — | Poor | Yes |

| 11 | F | 12.3 | 90 | T | 334.900 | CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD7 | Partial deletion chromosome 4 | Good | Yes |

| 12 | M | 4.0 | 100 | B | 45.500 | CD19, CD34, CD10 | — | Poor | No |

| 13 | M | 14.8 | 100 | B | 20.240 | CD10, CD19, CD20, DR, CD34+/−, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

| 14 | M | 1.8 | 100 | B | 17.810 | CD10, CD19, DR, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

| 15 | F | 3.7 | 100 | B | 108.700 | CD34, CD19, CD10, DR | Hyperdiploid | Poor | No |

| 16 | F | 2.7 | 100 | B | 196.000 | CD10, CD19, CD20, DR, CD34 | Hyperdiploid | Poor | No |

| 17 | M | 2.0 | 98 | T | 92.500 | CD5, CD2, CD7, CD3cy, CD10, CD4, CD8 | — | Poor | No |

| 18 | F | 1.9 | 98 | B | 124.560 | CD34, CD19, DR | t(4;11) | Poor | Yes |

| 19 | M | 5.7 | 100 | T | 16.800 | CD2, CD5, CD7, TdT, CD10+/− | — | Good | Yes |

| 20 | F | 3.5 | 98 | B | 78.400 | Tdt, CD10, CD19, CD20, DR | t(12;21) | Good | No |

| 21 | M | 8.11 | 98 | T | 21.990 | CD3cy, CD7, CD5, TdT, CD34, TCR | — | Good | Yes |

| 22 | M | 10.7 | 60 | B | 3.630 | CD10, CD19, CD22, CD34, TγδT | NT | Good | Yes |

| 23 | F | 9.10 | 99 | B | 34.190 | CD19, CD34, TdT | — | Poor | No |

| 24 | M | 11.1 | 99 | T | 310.000 | CD7, CD2, CD5, CD8, cyCD3, TdT | — | Poor | No |

| 25 | F | 9.3 | 90 | B | 6.970 | CD10, CD19, CD33, CD34, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

Patient no. . | Sex . | Age, y.mo . | %Blasts . | Lineage . | WBC count, 109/L . | Immunophenotype . | Genetic rearrangement . | GR* . | RR† . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 11.3 | 100 | B | 111.680 | CD10, CD19, CD34 | T(12;21) | Good | Yes |

| 2 | M | 6.11 | 100 | T | 15.760 | CD10, CD7, CD2, CD3cy, CD4, CD8 | — | Good | Yes |

| 3 | M | 2.10 | 84 | T | 118.740 | CD7, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD2, CD3+/− | — | Good | Yes |

| 4 | F | 11.10 | 100 | T | 198.510 | CD7, CD34, CD3cy, CD2, CD5, TdT | Partial deletion chromosome 1 | Poor | No |

| 5 | M | 14.5 | 100 | B | 40.600 | CD10, CD34, CD19, DR, CD33, CD13 | — | Good | No |

| 6 | M | 13.10 | 95 | B | 56.130 | CD19, CD79a-cy CD22, CD24, DR, | — | Good | Yes |

| 7 | M | 3.3 | 100 | B | 5.790 | CD10, CD19, CD24, TdT, CD34, CD38 | NT | Good | No |

| 8 | M | 9.4 | 20 | T | 3.650 | CD5, CD7, CD3cy, CD1a | — | Poor | Yes |

| 9 | M | 3.9 | 90 | B | 98.100 | CD34, CD19, CD10, DR, CD13, CD33, TdT | t(9;22) | Poor | No |

| 10 | M | 7.4 | 100 | T | 314.950 | CD3cy, CD4, CD8, CD10, CD7, CD5, TdT | — | Poor | Yes |

| 11 | F | 12.3 | 90 | T | 334.900 | CD2, CD3, CD4, CD8, CD7 | Partial deletion chromosome 4 | Good | Yes |

| 12 | M | 4.0 | 100 | B | 45.500 | CD19, CD34, CD10 | — | Poor | No |

| 13 | M | 14.8 | 100 | B | 20.240 | CD10, CD19, CD20, DR, CD34+/−, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

| 14 | M | 1.8 | 100 | B | 17.810 | CD10, CD19, DR, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

| 15 | F | 3.7 | 100 | B | 108.700 | CD34, CD19, CD10, DR | Hyperdiploid | Poor | No |

| 16 | F | 2.7 | 100 | B | 196.000 | CD10, CD19, CD20, DR, CD34 | Hyperdiploid | Poor | No |

| 17 | M | 2.0 | 98 | T | 92.500 | CD5, CD2, CD7, CD3cy, CD10, CD4, CD8 | — | Poor | No |

| 18 | F | 1.9 | 98 | B | 124.560 | CD34, CD19, DR | t(4;11) | Poor | Yes |

| 19 | M | 5.7 | 100 | T | 16.800 | CD2, CD5, CD7, TdT, CD10+/− | — | Good | Yes |

| 20 | F | 3.5 | 98 | B | 78.400 | Tdt, CD10, CD19, CD20, DR | t(12;21) | Good | No |

| 21 | M | 8.11 | 98 | T | 21.990 | CD3cy, CD7, CD5, TdT, CD34, TCR | — | Good | Yes |

| 22 | M | 10.7 | 60 | B | 3.630 | CD10, CD19, CD22, CD34, TγδT | NT | Good | Yes |

| 23 | F | 9.10 | 99 | B | 34.190 | CD19, CD34, TdT | — | Poor | No |

| 24 | M | 11.1 | 99 | T | 310.000 | CD7, CD2, CD5, CD8, cyCD3, TdT | — | Poor | No |

| 25 | F | 9.3 | 90 | B | 6.970 | CD10, CD19, CD33, CD34, TdT | — | Good | Yes |

— indicates not found; NT, not tested.

GR: an in vivo response to glucocorticoids after a 7-day prednisone prophase.

RR: an in vitro response to rapamycin.

Mononuclear cells from the 25 bone marrow samples were separated through Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH). The percentage of blasts in mononuclear-cell specimens was more than 90%, except for refractory ALL, in which it was 59.1%. Cells (1 × 106 cells/mL) were cultured in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany) RPMI 1640 (Cambrex Bio Science, Verviers, Belgium), supplemented with antibiotic and glutamine (Cambrex Bio Science) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere, with and without rapamycin (Rapamune; Wyeth Ayerst Laboratories, Marietta, PA).

Cell transfection, plasmids, and siRNA

Jurkat cells (2 × 107) in the logarithmic growth phase were resuspended in 400 μL serum-free RPMI 1640 and transfected with 20 μg plasmid DNA by electroporation at 250 V and 960 mF using the Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The cells were transferred to culture flasks and incubated in complete medium supplemented with 1 mg/mL G418 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to obtain stable lines. The cDNA coding for p65 (RelA), cloned in a pCMV4 vector carrying resistance for G418, was kindly donated by Dr Shao-Cong Sun (Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine).

For siRNA transfection, cells at a concentration of 5 × 105/mL were incubated for 24 hours in 6-well plates in medium without antibiotics. This was followed by transfection of the oligonucleotide 5′-ACCUAAUGCUGAGCUUAUAdTdT-3′ corresponding to the sense strand of the target sequence 5′-AAACCUAAUGCUGAGCUUAUA-3′ of human FKBP51 (Dharmacon Research, Chicago, IL) or of a scrambled duplex as control (Dharmacon Research). The siRNA or the scrambled oligo was transfected at the final concentration of 50 nM using Metafectene (Biontex, Munich, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Two days later, 5 μM doxorubicin was added to the culture medium and cells were harvested 5 hours later and processed for Western blot analysis or electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Analysis of apoptosis

We used the lipophylic cation 5,5′,6,6′ tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazol-carbocyanine iodide (JC-1) and flow cytometry to analyze the mitochondria membrane potential. In this procedure, the color of the dye changes from orange to green as the membrane potential decreases.25 Briefly, 5 × 105 cells were incubated for 10 minutes at 37°C with 10 μg/mL JC-1 (Molecular Probes, Leiden, The Netherlands), washed, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Phosphatidylserine externalization was investigated by annexin V staining in double or single fluorescence. Next, 5 × 105 cells were incubated with annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Pharmingen/Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) or phycoerythrin (PE; Alexis, San Diego, CA) conjugated in 100 μL binding buffer containing 10 mM HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid)/NaOH pH 7.5, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2 for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Subsequently, 400 μL of the same buffer was added to each sample and the cells were analyzed in the Becton Dickinson FACScan flow cytometer. The mouse monoclonal antibody, anti-CD7-FITC, -CD3-PE, or -CD20-PE (Pharmingen/Becton Dickinson), was added in double fluorescence tests. Caspase-3 activity was detected with the caspase-3 fluorometric assay kit (Perbio Science, Erembodegem, Belgium) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The cells (2 × 106) were lysed in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 130 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM NaPi, and 10 mM NaPPi, and 50 μg protein was analyzed.

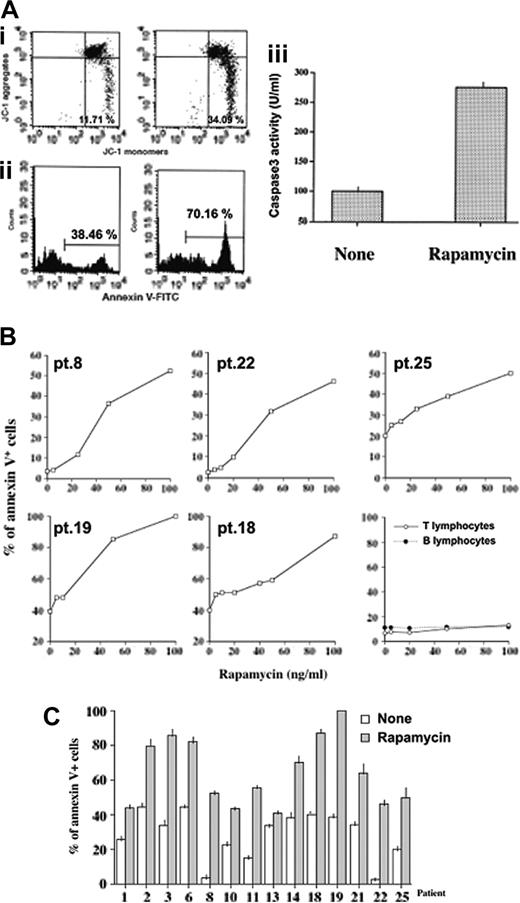

Rapamycin induces apoptosis of primary malignant lymphoblasts. (A) Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential (i), phosphatidyl-serine externalization (ii), and caspase 3 catalytic activity (iii) of cALL blasts cultured with rapamycin (50 ng/mL). After 6 hours of incubation, mitochondrial potential was analyzed by calculating the amount of JC-1 monomers by flow cytometry. Annexin V binding and caspase 3 activity were measured by flow cytometry and fluorometric assay, respectively, after 24 hours of incubation. The percentages on the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells. (B) Dose/response curve to rapamycin. Malignant lymphocytes from 5 different samples and peripheral B or T lymphocytes from a healthy donor were incubated with rapamycin at different concentrations. After 24 hours, the cells were harvested and apoptosis was evaluated by annexin V staining and flow cytometry. For B and T lymphocyte analysis, the whole PBMCs were acquired in flow cytometry, after which B or T cells were gated on the basis of CD3/SSc or CD20/SSc parameters, and the percentage of annexin V+ cells was calculated. Pt. indicates patient number. (C) Mean values ± standard deviation (SD) of rapamycin-induced apoptosis in responder samples. Apoptosis was evaluated by annexin V staining of ALL blasts, from the indicated patients, after 24 hours of incubation with or without rapamycin (100 ng/mL).

Rapamycin induces apoptosis of primary malignant lymphoblasts. (A) Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential (i), phosphatidyl-serine externalization (ii), and caspase 3 catalytic activity (iii) of cALL blasts cultured with rapamycin (50 ng/mL). After 6 hours of incubation, mitochondrial potential was analyzed by calculating the amount of JC-1 monomers by flow cytometry. Annexin V binding and caspase 3 activity were measured by flow cytometry and fluorometric assay, respectively, after 24 hours of incubation. The percentages on the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells. (B) Dose/response curve to rapamycin. Malignant lymphocytes from 5 different samples and peripheral B or T lymphocytes from a healthy donor were incubated with rapamycin at different concentrations. After 24 hours, the cells were harvested and apoptosis was evaluated by annexin V staining and flow cytometry. For B and T lymphocyte analysis, the whole PBMCs were acquired in flow cytometry, after which B or T cells were gated on the basis of CD3/SSc or CD20/SSc parameters, and the percentage of annexin V+ cells was calculated. Pt. indicates patient number. (C) Mean values ± standard deviation (SD) of rapamycin-induced apoptosis in responder samples. Apoptosis was evaluated by annexin V staining of ALL blasts, from the indicated patients, after 24 hours of incubation with or without rapamycin (100 ng/mL).

Cell lysates and Western blot analysis

For IκBα detection, cytosolic extracts were obtained by resuspending the cells in lysing buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 1 mM EDTA [ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid], 60 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1 mM PMSF [phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride], 50 μg/mL antipain, 40 μg/mL bestatin, 20 μg/mL chymostatin, 0.2% vol/vol Nonidet P-40) for 15 minutes in ice. For Akt, phospho-Akt, p65, and FKBP51 detection, whole-cell lysates were prepared by homogenization in modified RIPA buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholic acid, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 5 μg/mL aprotinin, 5 μg/mL leupeptin). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation. Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay. The cell lysate was boiled for 5 minutes in 1x SDS sample buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 12.5% glycerol, 1% SDS, 0.01% bromophenol blue) containing 5% beta-mercaptoethanol, run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto a membrane filter (Cellulosenitrate; Schleider and Schuell, Keene, NH), and incubated with the primary antibody. The anti-IκBα and -p65(RelA) were rabbit polyclonal antibodies from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); anti-Akt, anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308), and anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) were rabbit polyclonal antibodies purchased from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Anti-FKBP51 was a rabbit polyclonal antibody purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, United Kingdom). After a second incubation with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology), the blots were developed with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Nuclear extracts, EMSA, and oligonucleotides

Cell nuclear extracts were prepared by cell-pellet homogenization in 2 volumes of 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5 mM PMSF, and 10% glycerol vol/vol. Nuclei were centrifuged at 1000g for 5 minutes, washed, and resuspended in 2 volumes of the same solution. KCl was added to reach 0.39 M KCl. Nuclei were extracted at 4°C for 1 hour and centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 minutes. The supernatant was clarified by centrifugation and stored at -80°C. Protein concentration was determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay. The NF-κB consensus 5′-CAACGGCAGGGGAATCTCCCTCTCCTT-3′ oligonucleotide was end-labeled with γ-[32P] adenosine triphosphate (ATP; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) using a polynucleotide kinase (Roche). End-labeled DNA fragments were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes with 5 μg nuclear protein, in the presence of 1 μg poly(dI-dC), in 20 μL of a buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 5% glycerol vol/vol. In competition assays, a 50× molar excess of NF-κB or nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) cold oligonucleotide was added to the incubation mixture. Protein-DNA complexes were separated from free probe on a 6% polyacrylamide wt/vol gel run in 0.25× Tris borate buffer at 200 mV for 3 hours at room temperature. The gels were dried and exposed to x-ray film (Kodak AR).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the apoptosis data was performed by means of the paired Student t test. The chi square test was used to compare categorical data.

Results

Rapamycin-induced apoptosis of cALL blasts

We evaluated apoptosis in cultured mononuclear cells from 25 bone marrow samples obtained from patients with cALL (15 B-cALL and 10 T-cALL) and exposed to rapamycin. We found that rapamycin significantly (P = .004) increased basal-cell death in 14 (7 B-cALL and 7 T-cALL) of the 25 leukemia samples (56%; Table 1). Thus, 46.6% of B-cALL and 70.0% of T-cALL samples responded to the drug (responder group). Interestingly, the response of blasts to rapamycin in vitro correlated with prednisone response in vivo (P = .01). Indeed, 11 of the 14 patients who responded to prednisone in vivo responded to rapamycin in vitro. Similarly, 8 of the 11 poor responders to prednisone in vivo, including the 2 hyperdiploid patients, did not respond to rapamycin in vitro. It is noteworthy that the patient with the t(4;11) rearrangement (patient 18) was among the 3 poor responders to glucocorticoids who responded to rapamycin. Rapamycin caused mitochondrial depolarization after 6 hours of incubation (Figure 1A). After an additional 19 hours, the proportion of annexin V+ cells was increased more than 80% with an enhancement of caspase 3 catalytic activity of more than 100%. Figure 1B shows dose/response curves relating to 5 donors. At 20 ng/mL, rapamycin increased basal-cell death by at least 25%. The apoptotic effect increased as the rapamycin dose increased. The active doses of rapamycin were within the range considered to be therapeutically achievable.26 Indeed, although the maximum serum level should not exceed 15 ng/mL, it must be taken into account that approximately 95% of rapamycin is vehicled by red blood cells because of its high lipophilicity.26 Rapamycin did not appear to affect the survival of normal peripheral T and B lymphocytes (Figure 1B). The mean values of apoptosis in the rapamycin-responsive samples are shown in Figure 1C; each experiment was in triplicate.

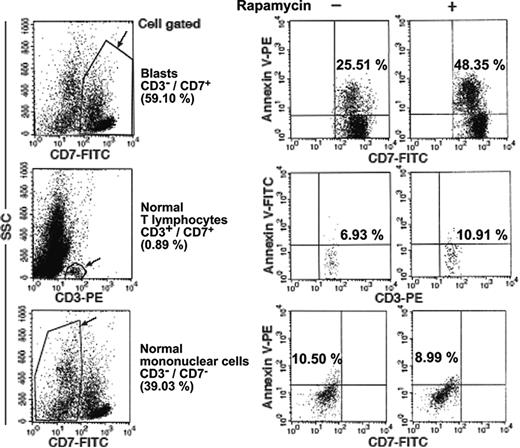

Normal bone marrow mononuclear cells display low sensitivity to cell-death stimuli compared with blasts. Flow cytometry evaluation of apoptosis of leukemic (CD3-/CD7+) or normal (CD3+/CD7+, CD3-/CD7-) mononuclear-cell populations (patient 8), incubated for 24 hours with 25 ng/mL rapamycin. The cells were gated on the basis of FL1 (CD7-FITC)/side scatter (SSc) or FL2(CD3-PE)/SSc parameters and the percentage of annexin-positive cells was measured.

Normal bone marrow mononuclear cells display low sensitivity to cell-death stimuli compared with blasts. Flow cytometry evaluation of apoptosis of leukemic (CD3-/CD7+) or normal (CD3+/CD7+, CD3-/CD7-) mononuclear-cell populations (patient 8), incubated for 24 hours with 25 ng/mL rapamycin. The cells were gated on the basis of FL1 (CD7-FITC)/side scatter (SSc) or FL2(CD3-PE)/SSc parameters and the percentage of annexin-positive cells was measured.

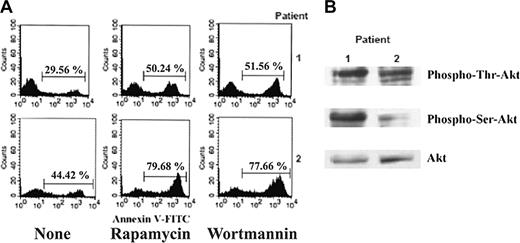

The PI3k/Akt pathway plays a role in ALL blast apoptosis. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis, by annexin V-FITC staining, of ALL blasts incubated for 24 hours with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). The percentages over the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells. (B) Western blotting assay of phospho-Akt, at Ser 473 or Thr 308, in cell lysates from the same samples.

The PI3k/Akt pathway plays a role in ALL blast apoptosis. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis, by annexin V-FITC staining, of ALL blasts incubated for 24 hours with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). The percentages over the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells. (B) Western blotting assay of phospho-Akt, at Ser 473 or Thr 308, in cell lysates from the same samples.

Rapamycin enhances doxorubicin-induced apoptosis of ALL cells. Mean values ± SD of apoptosis of ALL blasts, from 8 responder samples (A; patients 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, 14, 18, 19) and 7 nonresponder samples (B; patients 4, 5, 7, 9, 12, 15, 20), incubated for 24 hours with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or doxorubicin (0.5 μM). (C) Dose/response effect of rapamycin on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. ALL cells (patient 7) were cultured with and without 0.5 μM doxorubicin and with or without rapamycin at the indicated concentrations; 24 hours later, apoptosis was measured by annexin V staining. (D) Flow cytometry diagrams of apoptosis of blasts, from patient 20, cultured with doxorubicin at the indicated concentrations, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL). The percentages on the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells.

Rapamycin enhances doxorubicin-induced apoptosis of ALL cells. Mean values ± SD of apoptosis of ALL blasts, from 8 responder samples (A; patients 1, 2, 3, 6, 11, 14, 18, 19) and 7 nonresponder samples (B; patients 4, 5, 7, 9, 12, 15, 20), incubated for 24 hours with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or doxorubicin (0.5 μM). (C) Dose/response effect of rapamycin on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis. ALL cells (patient 7) were cultured with and without 0.5 μM doxorubicin and with or without rapamycin at the indicated concentrations; 24 hours later, apoptosis was measured by annexin V staining. (D) Flow cytometry diagrams of apoptosis of blasts, from patient 20, cultured with doxorubicin at the indicated concentrations, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL). The percentages on the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells.

Normal bone marrow cells were less sensitive than cALL blasts to rapamycin-induced apoptosis

We next evaluated if rapamycin is cytotoxic for the normal hematopoietic counterpart of cALL cells. To this aim, we used annexin V in double fluorescence and flow cytometry to examine the effect of rapamycin in diverse bone marrow cell subpopulations from a patient with refractory cALL (patient 8). Figure 2 shows the flow cytometry diagrams of rapamycin-induced apoptosis of normal mononuclear cells (CD3+ or CD7-) compared with that of CD3-/CD7+ blasts. At a rapamycin concentration between 20 ng/mL and 100 ng/mL, the extent of apoptosis of normal bone marrow mononuclear cells was less than 15%. These results suggested that rapamycin counteracted a cell signaling pathway that is deregulated in cALL blasts.

Rapamycin inhibits doxorubicin-induced NF-κB activation in ALL blasts. (A) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts from ALL cells (patient 5) cultured for 5 hours with 0.5 μM doxorubicin, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). A competition assay performed with the same NF-κB cold oligo or an unrelated oligo (see “Materials and methods”) indicated the specificity of the NF-κB band. (B) Flow cytometry diagrams of apoptosis of ALL blasts, from the same patient, cultured for 24 hours with 0.5 μM doxorubicin, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). The percentages over the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells.

Rapamycin inhibits doxorubicin-induced NF-κB activation in ALL blasts. (A) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts from ALL cells (patient 5) cultured for 5 hours with 0.5 μM doxorubicin, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). A competition assay performed with the same NF-κB cold oligo or an unrelated oligo (see “Materials and methods”) indicated the specificity of the NF-κB band. (B) Flow cytometry diagrams of apoptosis of ALL blasts, from the same patient, cultured for 24 hours with 0.5 μM doxorubicin, with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). The percentages over the bars indicate the amount of annexin V-positive cells.

Rapamycin does not enhance doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in RelA-hyperexpressing transfectants. (A) Western blotting analysis of p65 (RelA) expression levels in cell lysates obtained from wild-type Jurkat cells and void vector- or RelA-stable transfectants. (B) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts obtained from Jurkat wild-type cells cultured for 5 hours with and without 5 μM doxorubicin and with or without rapamycin (100 ng/mL), and RelA- or void vector-stable transfectants. (C) Analysis of apoptosis of RelA- or void vector-stable transfectants cultured with and without 5 μM doxorubicin and with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL). After 24 hours of incubation, cells were harvested and cell death was analyzed by propidium iodide incorporation in flow cytometry. Results are from 4 different experiments, each of which was in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Rapamycin does not enhance doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in RelA-hyperexpressing transfectants. (A) Western blotting analysis of p65 (RelA) expression levels in cell lysates obtained from wild-type Jurkat cells and void vector- or RelA-stable transfectants. (B) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts obtained from Jurkat wild-type cells cultured for 5 hours with and without 5 μM doxorubicin and with or without rapamycin (100 ng/mL), and RelA- or void vector-stable transfectants. (C) Analysis of apoptosis of RelA- or void vector-stable transfectants cultured with and without 5 μM doxorubicin and with and without rapamycin (100 ng/mL). After 24 hours of incubation, cells were harvested and cell death was analyzed by propidium iodide incorporation in flow cytometry. Results are from 4 different experiments, each of which was in triplicate. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

FKBP51 controls drug-induced NF-κB activaton in human leukemia. (A) Western blotting analysis of FKBP51 expression levels in cell lysates obtained from transfected or nontransfected Jurkat cells, with FKBP51 siRNA or the scrambled oligo as control. (B) Western blotting analysis of IκBα expression levels in cells transfected with FKBP51 siRNA and cultured with or without doxorubicin (5 μM) for 5 hours. (C) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts from Jurkat cells transfected with FKBP51 siRNA and cultured with or without doxorubicin (5 μM) for 5 hours. A competition assay, with the same -κB cold oligo or an unrelated oligo (see “Materials and methods”), indicated the specificity of the NF-κB band.

FKBP51 controls drug-induced NF-κB activaton in human leukemia. (A) Western blotting analysis of FKBP51 expression levels in cell lysates obtained from transfected or nontransfected Jurkat cells, with FKBP51 siRNA or the scrambled oligo as control. (B) Western blotting analysis of IκBα expression levels in cells transfected with FKBP51 siRNA and cultured with or without doxorubicin (5 μM) for 5 hours. (C) EMSA analysis of nuclear extracts from Jurkat cells transfected with FKBP51 siRNA and cultured with or without doxorubicin (5 μM) for 5 hours. A competition assay, with the same -κB cold oligo or an unrelated oligo (see “Materials and methods”), indicated the specificity of the NF-κB band.

Akt was activated in rapamycin-sensitive samples

To determine if the phosphatidyl-inositol pathway is involved in blast survival, we investigated the effect of the PI3k inhibitor wortmannin27 on cALL-cell death. Our data show that wortmannin induced levels of apoptosis comparable to those induced by rapamycin in 11 of the 15 samples from the responder group, whereas none of the samples from nonresponder patients underwent apoptosis when stimulated with wortmannin. Figure 3A shows the flow cytometry diagrams of annexin V binding to cALL blasts from 2 samples, cultured for 24 hours with rapamycin (100 ng/mL) or wortmannin (1 μM). Analysis of phospho-Akt by Western blotting assay revealed high expression of both Ser473- and Thr301-phospho-Akt in patient 1 and of Thr301-phospho-Akt in patient 2 (Figure 3B). These findings suggest that the PI3k/Akt pathway is involved in the survival of malignant lymphoblasts.

Rapamycin enhanced doxorubicin-induced apoptosis

Anthracycline compounds are widely used to treat leukemias. We investigated if rapamycin could enhance doxorubin-induced cALL blast apoptosis. To this end, we cultured primary leukemic cells from 15 bone marrow samples (8 samples responding and 7 nonresponding to rapamycin) for 24 hours with 500 nM doxorubicin, in the presence and absence of rapamycin (100 ng/mL), and then evaluated apoptosis by measuring annexin V staining in flow cytometry. In responder samples (Figure 4A), both rapamycin and doxorubicin significantly increased cell death over basal levels (P < .001 and .005, respectively). The addition of rapamycin to doxorubicin-exposed cells increased apoptosis versus cells exposed to doxorubicin alone, in both responder (Figure 4A; P = .001) and nonresponder samples (Figure 4B; P = .001). Therefore, rapamycin exerts a proapoptotic effect even when it is unable to directly activate cell death. As is shown in Figure 4C, the cooperative effect of rapamycin plus doxorubicin was detected at doses more than or equal to 20 ng/mL. Figure 4D shows a sample in which rapamycin or doxorubicin alone did not induce cell death, whereas the 2 drugs together enhanced basal apoptosis by more than 90%.

Rapamycin inhibited doxorubicin-induced NF-κB/Rel activation in cALL cells

To identify the mechanism by which rapamycin enhanced doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in cALL blasts, we investigated if rapamycin was able to counteract the induction of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors20 in cALL blasts. In fact, anthracycline compounds activate transcription factors that play an important role in chemoresistance.21 As shown in Figure 5A, rapamycin, but not wortmannin, inhibited the translocation of NF-κB/Rel complexes in blast nuclei. Furthermore, rapamycin, but not wortmannin, enhanced doxorubicin-induced apoptosis (Figure 5B). These results suggest that rapamycin can sensitize cALL blasts to anthracycline drugs by inhibiting activation of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors through a mechanism independent of PI3k/Akt inhibition.

The enhancement of apoptosis by rapamycin was antagonized by p65(RelA) hyperexpression

To determine if rapamycin-induced enhancement of apoptosis was related to NF-κB down-modulation, we investigated whether rapamycin increased apoptosis when NF-κB was overexpressed. In these experiments we used the Jurkat leukemic cell line in which we transfected PCMV4 vector carrying the p65 subunit of NF-κB and resistance to genetycin, thus obtaining stable transfectants (Figure 6A). As shown in Figure 6B, doxorubicin activated NF-κB in Jurkat cells, whereas rapamycin antagonized this effect. Moreover, as expected, p65 transfectants constitutively expressed NF-κB in nuclei, but control cells did not. We subsequently incubated p65- and void vector-stable transfectants both with and without doxorubicin for 24 hours, and analyzed apoptosis by propidium iodide incorporation. Rapamycin did not enhance apoptosis in cells hyperexpressing p65. In fact, it increased apoptosis by 59.4% in control cells (P = .032) and by only 3.9% in RelA hyperexpressing Jurkat cells (Figure 6C). We therefore conclude that down-modulation of NF-κB/Rel transcription factors is a mechanism by which rapamycin enhances apoptosis and that rapamycin can cooperate with NF-κB-inducing drugs.

The rapamycin-binding protein FKBP51 controls NF-κB activation in leukemia

The immunophilin FKBP51 is required for IKK-α functioning.24 Rapamycin specifically binds to FKBP51 and inhibits its peptidyl-prolyl-isomerase activity.23 FKBP51 was first cloned in lymphocytes in which it was abundant.23 To assess the role of FKBP51 in the NF-κB activation pathway in human leukemia, we down-modulated immunophilin levels in Jurkat cells using the siRNA technique. As shown in Figure 7A, the expression levels of FKB51 were remarkably decreased in Jurkat cells transfected with FKBP51 siRNA than in cells incubated with control medium or transfected with a scrambled oligonucleotide. We then investigated the ability of doxorubicin to induce IκBα degradation and NF-κB nuclear translocation when FKBP51 was down-modulated. Figure 7B shows that IκBα levels decreased in control- or scrambled-oligo-transfected cells cultured with doxorubicin, but not when FKBP51 was down-modulated. Accordingly, NF-κB complexes were not detected by EMSA in nuclear extracts from FKBP51 siRNA-transfected cells (Figure 7C). These findings suggest that FKBP51 controls NF-κB activation in human leukemia.

Discussion

mTOR mediates PI3k/Akt-driven cell proliferation and survival.12,15-18 In line with this finding, rapamycin has been reported to exert its major anticancer effect in neoplasias that lack the PI3k antagonist, phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN).12,28 mTOR controls the synthesis of proteins essential for cell-cycle progression and cellular proliferation14-17 by phosphorylating 2 key translational regulators: the initiation factor 4E binding protein (4E-BPI),16 and the 70-kDa S6 ribosomal protein kinase (p70S6k).14 Several lines of evidence support the view that abnormal survival signals from the phosphatidyl-inositol cascade lead to neoplastic transformation of lymphoid precursors.5-7,19 The finding that rapamycin exerts antiproliferative and apoptotic effects on B-precursor leukemia, in vitro and in vivo, by mechanisms involving the inhibition of mTOR and p70S6k,19 provided the rationale for new therapeutic strategies against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In agreement with these findings, we show that rapamycin induces apoptosis of blasts in 56% of bone marrow samples from patients with cALL. Moreover, we found that apoptosis can be induced, in responder samples, also by inhibiting PI3k using the specific inhibitor wortmannin.27 These findings, together with the detection of constitutive activation of Akt in 2 different cALL bone marrow samples, support previous evidence5-7,19 that the phosphatidyl-inositol pathway is involved in blast survival.

We also found that rapamycin increased doxorubicin-induced cell death, even in nonresponder samples, whereas the PI3k inhibitor wortmannin did not act in concert with doxorubin. These findings suggest that rapamycin may also exert a proapoptotic activity by mechanisms independent of PI3k/Akt/mTOR inhibition. We demonstrate that the immunophilin FKBP51 controls drug-induced NF-κB activation in human leukemia, which explains the proapoptotic effect of rapamycin. Immunophilins are the first target of the drug23,29 and, in fact, the binding of rapamycin to FKBP12 is crucial for mTOR inhibition.29 Immunophilins are abundant cytosolic proteins endowed with inherent peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity that is inhibited by drug ligand binding.23,29 Given the biologic relevance of this class of proteins,24,30-32 it is not surprising that rapamycin induces effects independent of PI3k/Akt/mTOR inhibition.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that rapamycin might be effective in the treatment of cALL, despite the biologic heterogeneity of the disease. Finally, our study, in agreement with other reports showing that immunophilins are involved in a host of diseases that do not necessarily involve the same signaling pathway,33,34 opens the way to the development of a range of new drugs specifically targeting immunophilins.34

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 5, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0929.

Supported by funds from the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MIUR).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal