Abstract

Although results from preclinical studies in animal models have proven the concept for use of anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibodies in cancer immunotherapy, 2 major obstacles have hindered their successful application for human cancer therapy. First, the lack of in vitro correlates of the antitumor effect of the antibodies makes it difficult to screen for the most efficacious antibody by in vitro analysis. Second, significant autoimmune side effects have been observed in a recent clinical trial. In order to address these 2 issues, we have generated human CTLA4 gene knock-in mice and used them to compare a panel of anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies for their ability to induce tumor rejection and autoimmunity. Surprisingly, while all antibodies induced protection against cancer and demonstrated some autoimmune side effects, the antibody that induced the strongest protection also induced the least autoimmune side effects. These results demonstrate that autoimmune disease does not quantitatively correlate with cancer immunity. Our approach may be generally applicable to the development of human therapeutic antibodies.

Introduction

Antibodies have emerged as one of the most valuable immunotherapeutics for cancer.1 Therapeutic antibodies can be divided into 2 categories. The first category of antibodies binds directly to cancer cells.1-3 This binding results in the death of cancer cells by immune-dependent and/or -independent mechanisms.4 The second category of antibodies causes tumor rejection by binding to and activating cells of the immune system, such as the T lymphocytes.5,6 Because this category of antibodies targets lymphocytes regardless of antigen specificity, a major concern of immunotherapy based on this category of antibodies is the risk of severe autoimmune side effects.7

A prominent example of a category II therapeutic antibody is the anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) antibody.6 CTLA-4 is the high-affinity receptor for B7-1 and B7-2.8,9 Anti–CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been shown to promote antitumor immunity against a variety of tumors including colon carcinoma,10 fibrosarcoma,10 prostate cancer,11-13 melanoma,14-16 ovarian carcinoma,17 mammary carcinoma,18 and myeloma.19 These observations have led to enthusiasm for the translation of CTLA-4 antibody therapy to human cancer. More recently, an anti–human CTLA-4 mAb has been generated and tested in clinical trials of patients with advanced ovarian cancer and melanoma.20,21 In one of these trials, anti–CTLA-4 mAb induced grades 3 and 4 autoimmune toxicities.20

To facilitate translation of this concept, it would be helpful to establish preclinical models to identify anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies that can induce anticancer immunity with acceptable autoimmune side effects. Unfortunately, in vitro cultures of human T cells have proven to be an unsuitable model, as the same antibody can have opposite effects on different clones of T cells in the same culture.22 We have recently reported the use of the human peripheral blood lymphocyte–severe combined immunodeficient (PBL-SCID) model to screen for therapeutic anti–CTLA-4 antibodies in vivo.23 While this model allows us to demonstrate the protective effect of the antibody against human Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) lymphoma, it does not permit us to evaluate autoimmune side effects. Taking advantage of the fact that human CTLA-4 is capable of interacting with mouse B7-1 and B7-2,9,24 we created a mouse with a knock-in of the human CTLA4 gene. Using this model we compared the autoimmune side effects and cancer immunity of 3 anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies. Surprisingly, the antibody that induced the most potent cancer immunity provoked the least autoimmune side effects. These results demonstrate that autoimmunity does not quantitatively correlate with cancer immunity and that selective tuning of cancer immunity over autoimmunity is possible with careful choice of antibodies.

Materials and methods

Antibodies

Anti–human CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies L3D10, K4G4, and L1B11 have been described previously.23 Antibody was purified from hybridoma culture supernatant using a Protein G column. Mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Creation of a human CTLA-4 knock-in construct

The P1 clone containing a 100-kb murine CTLA4 gene was purchased from Genomic Systems (St Louis, MO). A 3.8-kb DNA fragment containing the 5′ promoter region, exon 1, and part of intron 1 of the murine Ctla4 gene was amplified using 2 primers: CTGAAGCTTCAGTTTCAAGTTGAG, which corresponded to a sequence starting at base 734 of the 5′ promoter region, and TTGGATGGTGAGGTTCACTC, which corresponded to base 4524 of the exon 2 region. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product was digested with HindIII and the 3.0-kb fragment was cloned into a HindIII-digested pFlox vector (Dr Raj Muthusamy, Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH). The vector was a 6.5-kb plasmid containing a neomycin resistance gene/HSV (herpes simplex virus) thymidine kinase gene cassette flanked by loxP sites.

DNA containing a 14-kb fragment of the human CTLA4 gene was prepared from a lambda phage clone25,26 and digested with the restriction enzyme HindIII. A 3.2-kb HindIII fragment containing part of intron 1, exon 2, intron 2, and exon 3 of the human CTLA4 gene was purified and inserted into a HindIII-digested pBluescript plasmid. Plasmid DNA with the insert in the correct orientation was linearized by XhoI digestion and partially digested with BamHI to obtain a 3.2-kb BamHI fragment for use in further cloning. The pFlox plasmid containing a 3-kb exon 1 of mouse CTLA-4 was linearized by XhoI digestion and partially digested with BamHI. The 9.5-kb fragment was purified and ligated with a 3.2-kb fragment of human CTLA4 exons 2 and 3.

A 2.9-kb DNA fragment containing part of intron 3, exon 4, and part of the 3′ sequence of the murine Ctla4 gene was cloned from the P1 clone using primers ATCCTCTAGAAGCTTCAAAGCAGGTTATCA, corresponding to base 6160 through base 6181 of intron 3, and TCTAGTCGACCACAGAGAGTCAAGGCCCTG, corresponding to base 8617 through base 8588 of the 3′ region. The PCR product was digested by XbaI and SalI and inserted into the pFlox clone containing mouse Ctla4 exon 1 and human Ctla4 exons 2 and 3. The final construct is illustrated in Figure 1A.

Preparation of embryonic stem cells with a disrupted humanized CTLA-4 transgene

Embryonic stem (ES) cell line R1 was transfected with the DNA construct by electroporation (Figure 1A), and drug-resistant ES cell colonies were obtained as described.27 To verify that homologous recombination had occurred, DNA was extracted from ES clones for analysis by PCR. Fragments were amplified using forward primer CCAAGACTCCACGTCTCCAG, corresponding to a region upstream of exon 1 of the mouse Ctla4 gene that is outside of the region used in the transgene construct, and reverse primer CCTCTGAGCATCCTTAGCAC, corresponding to a region in exon 2 of the human CTLA4 gene. These 2 primers gave rise to a PCR product of 3.3 kb only when the human exon was inserted into the mouse Ctla4 gene by homologous recombination. Eight of 153 DNA samples screened were positive for this product. The positive clones were analyzed by Southern blot to further confirm homologous recombination. Briefly, the genomic DNA from PCR-positive and -negative ES clones were isolated, digested with EcoRI, and transferred to Nylon membrane (Osmonics, Westborough, MA). A 0.9-kb probe was generated by PCR, targeting the region upstream from exon 1 between the EcoRI and HindIII sites using primers CTGCAGTGAACACCCCTCTC and ACGTCTCCAGGTCCTCAGAG. The probe was labeled with 32P using the DECAprime DNA labeling kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), and hybridized to the membrane. The blot was exposed to BIOMAX MS film (Kodak, Rochester, NY) with a Kodak HE intensifying screen for 2 days at –70°C. The endogenous murine Ctla4 gene yielded a band of 4.7 kb, whereas homologous recombination yielded a band of 7.0 kb by the replacement of the 0.9-kb murine exon 2 with the 3.2-kb human exons 2 and 3.

Generation of ES cells with a functional humanized CTLA-4 locus by Cre-mediated excision of the Neo-TK cassette

To remove the Neo-TK selection cassette, we transfected ES cells of clone no. 63 with the pCre-Pac plasmid described by Taniguchi et al,28 by electroporation. Two sets of PCR reactions were carried out to detect the floxed and deleted alleles of the CTLA4 locus. The first PCR reaction used 5′-TCCCTCTCAGACACCTCTGC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-GTCATAAACATCTCTCAGGTAA-3′ as the reverse primer. This reaction amplified the alleles in which Neo/TK had been deleted with a product of 1.1 kb. While this reaction should theoretically also amplify the endogenous murine Ctla4 alleles, the PCR conditions used did not allow amplification of a large product of 4 kb. The second PCR reaction used 5′-TCCCTCTCAGACACCTCTGC-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-CGACCTGTCCGGTGC-3′ as the reverse primer.

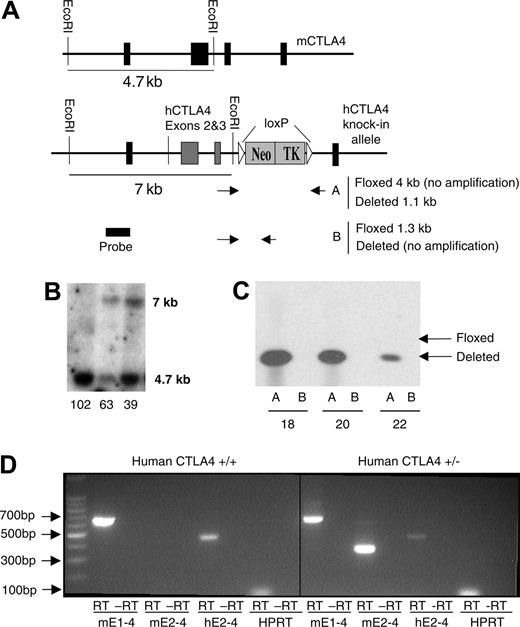

Creation of human CTLA4 knock-in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the structure of construct. The primer positions for screening the floxed and deleted genotypes are also illustrated. PCR Reaction A used primers outside the loxP sites spanning the Neo/TK gene. A successful excision (deleted) of Neo/TK produced a 1.1-kb fragment, whereas undeleted (floxed) Neo/TK did not produce a fragment due to the PCR conditions used. PCR Reaction B used a forward primer outside of and a reverse primer within the Neo/TK cassette. (B) Southern blot of DNA from ES cells transfected with the human CTLA4 construct. A 7-kb band represents successful homologous recombination with the human CTLA4 construct, whereas a 4.7-kb band represents an unaltered mouse Ctla4 gene. (C) Excision of Neo/TK by Cre-recombinase. As depicted schematically in panel A, Reaction A produced the expected 1.1-kb fragment, whereas Reaction B amplified no fragment, consistent with successful deletion of Neo/TK. (D) Expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 RNA in homozygous (left panel) and heterozygous (right panel) knock-in mice. Spleen cells from human CTLA4+/– and human CTLA4+/+ mice were stimulated for 30 hours in vitro with 0.1 μg/mL anti-CD3 mAb 2C11. RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was performed. Primers spanning the full-length CTLA4 RNA sequence were used to confirm that full-length RNA of the knock-in gene was being expressed (left reaction), whereas those that were specific for either mouse (mE2) or human (hE2) CTLA-4 exon 2 were used to identify mouse and human CTLA4, respectively.

Creation of human CTLA4 knock-in mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the structure of construct. The primer positions for screening the floxed and deleted genotypes are also illustrated. PCR Reaction A used primers outside the loxP sites spanning the Neo/TK gene. A successful excision (deleted) of Neo/TK produced a 1.1-kb fragment, whereas undeleted (floxed) Neo/TK did not produce a fragment due to the PCR conditions used. PCR Reaction B used a forward primer outside of and a reverse primer within the Neo/TK cassette. (B) Southern blot of DNA from ES cells transfected with the human CTLA4 construct. A 7-kb band represents successful homologous recombination with the human CTLA4 construct, whereas a 4.7-kb band represents an unaltered mouse Ctla4 gene. (C) Excision of Neo/TK by Cre-recombinase. As depicted schematically in panel A, Reaction A produced the expected 1.1-kb fragment, whereas Reaction B amplified no fragment, consistent with successful deletion of Neo/TK. (D) Expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 RNA in homozygous (left panel) and heterozygous (right panel) knock-in mice. Spleen cells from human CTLA4+/– and human CTLA4+/+ mice were stimulated for 30 hours in vitro with 0.1 μg/mL anti-CD3 mAb 2C11. RNA was extracted and RT-PCR was performed. Primers spanning the full-length CTLA4 RNA sequence were used to confirm that full-length RNA of the knock-in gene was being expressed (left reaction), whereas those that were specific for either mouse (mE2) or human (hE2) CTLA-4 exon 2 were used to identify mouse and human CTLA4, respectively.

Production of chimeric and transgenic mice

Chimeric mice were prepared by an aggregation method essentially as described.27 The chimera mice were bred to C57BL/6 mice to obtain founders with germ-line transmission of CTLA4 knock-in allele. The founders were then backcrossed to either C57BL/6 or BALB/c background for at least 6 generations. Homozygous mice were used for screening anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies.

Experimental animals and tumor cell lines

P1CTL transgenic mice expressing a T-cell receptor specific for the P1A35-43:Ld complex have been previously described.29 BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories under contract from the National Cancer Institute. All mice were maintained in the University Laboratory Animal Research Facility at the Ohio State University under specific pathogen-free conditions. MC38 colon carcinoma cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA).

Analysis of human CTLA-4 RNA and protein expression

Spleen cells were obtained from human CTLA4+/– and human CTLA4+/+ C57BL/6 mice and stimulated with anti-CD3 (2C11; 0.1 μg/mL) for 30 hours in culture. Following culture, total RNA was isolated and a reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR was performed with cDNA from stimulated splenocytes to amplify the full-length CTLA4 sequence from exons 1 to 4. The forward primer began at base pair 5 on mouse exon 1 (5′-CTTGTCTTGGACTCCGGAGGTAC-3′) and the reverse primer at base pair 652 on mouse exon 4 (5′-AAGGCTGAAATTGCTTTTCACATTC-3′) for a total amplified fragment size of 648 base pairs. To determine the coordinate expression of both mouse and human CTLA4 genes, cDNA was amplified with forward primers specific for mouse (5′-TGTGCCACGACATTCACAGA-3′) or human exon 2 (5′-GAGGCATCGCCAGCTTTGTG-3′) and a common reverse primer for mouse exon 4 (5′-CACATAGACCCCTGTTGTAAGA-3′). The amplified fragment using forward and reverse primers for mouse Ctla4 was 354 base pairs (bp), whereas the fragment using a forward primer for human CTLA4 was 455 base pairs. Forward and reverse primers for hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) were used as an internal control and gave rise to a 100-bp product.

To determine if human (hu) CTLA-4 protein was expressed properly, we bred P1CTL transgenic mice with huCTLA4+/– mice to create P1CTL+huCTLA4+/– mice. Freshly harvested spleens from these mice were stimulated with 0.1 μg/mL P1A peptide and harvested after 66 hours in culture. Spleen cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti–mouse CD3, phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–mouse CTLA-4 (intracellular), and CyChrome-conjugated anti–human CTLA-4 (intracellular). To further confirm that CTLA-4 protein was appropriately regulated we also stained naive spleens from wild type (WT), human CTLA4+/–, and human CTLA4+/+ C57BL/6 mice. Spleen cells were stained with PerCP-conjugated anti–mouse CD4, FITC-conjugated anti–mouse CD25, PE-conjugated anti–mouse CTLA-4 (intracellular), and allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti–human CTLA-4 (intracellular). Conjugated antibodies and CytoFix/CytoPerm intracellular staining kit were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Tumorigenicity assay

Mice used for tumorigenicity studies have been backcrossed to C57BL/6 for at least 6 generations. MC38 cells (5 × 105) suspended in serum-free RPMI (100 μL) were injected subcutaneously in the lower abdomen of mice. For the minimal disease model, mice were treated once a week beginning on day 2. In the established disease model, mice were treated every 4 days with treatments beginning 10 to 14 days after challenge. In both models, the tumor-bearing mice received identical doses of either anti–human CTLA-4 mAb or control mouse IgG (200 μg/mouse per injection). Tumor size and incidence were determined every 2 to 5 days by physical examination. The tumor volume was calculated using the following established formula: volume = 1/2 (long × short2 ). All mice were killed when the tumor volume reached 4000 mm3. The number of days required for tumors to reach this end point was used for survival analysis.

Detection of anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.

Anti-DNA antibodies were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to published procedure.30

Immunofluorescence for antibody and complement deposition in the kidney glomerulus

Frozen sections of kidney were prepared from euthanized mice and fixed in acetone. After blocking with 10% normal goat serum, the sections were stained with Rhodamine-conjugated goat anti–mouse IgG and FITC-conjugated goat anti–mouse C3 antibodies (ICN Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA).

Results

Functional replacement of mouse CTLA-4 gene with its human homologue

The gene encoding CTLA-4 is composed of 4 exons in both mice and humans, with 76% overall homology between murine and human CTLA-4 proteins and 100% homology between their cytoplasmic domains.25,26 Since human CTLA-4 is able to bind to murine B7-1 and B7-2,9,24 it is likely that the interaction of human CTLA-4 and murine B7 would maintain normal signal transduction by CTLA-4. We have created a chimeric DNA construct in which the exons coding for the extracellular (exon 2) and transmembrane (exon 3) domains of murine CTLA-4 have been replaced with those of human CTLA-4 (Figure 1A). As the gene product of exon 1 is a signal peptide not expressed in the mature protein, and the cytoplasmic domain (exon 4) is completely conserved between human and mouse, replacement of only exons 2 and 3 was required to create a humanized CTLA-4 knock-in mouse.

We transfected an embryonic stem (ES) cell line R1 with the human CTLA-4 DNAconstruct in Figure 1A by electroporation.After selection with G418, DNAwas isolated from the drug-resistant ES cell clones and screened by PCR for homologous recombination, which was then confirmed by Southern blot (Figure 1B). Probing for a sequence at the 5′ end of the CTLA4 gene, homologous recombination of the human CTLA4 knock-in gene yielded a band of 7.0 kb, whereas the endogenous mouse CTLA-4 gene yielded a band of 4.7 kb. ES cell clone 63, which had undergone homologous recombination, was transfected with the plasmid pCre-Pac that expresses both the Cre-recombinase and puromycin resistance gene. After selection with puromycin and potential excision of Neo/TK by Cre-recombinase, we further selected with gancyclovir, which eliminated all cells in which the Neo/TK gene was not excised. PCR analysis of DNA from several surviving colonies indicated that the Neo/TK cassette was excised from the knock-in locus (Figure 1C). Based on the analysis of DNA and RNA, ES cell clone 20 was chosen for the production of chimera mice, which were bred with C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice to obtain germ-line transmission of the human CTLA-4 gene. Those mice that have been backcrossed to C57BL/6 for at least 6 generations and homozygous for huCTLA-4 were used for tumorigenicity studies.

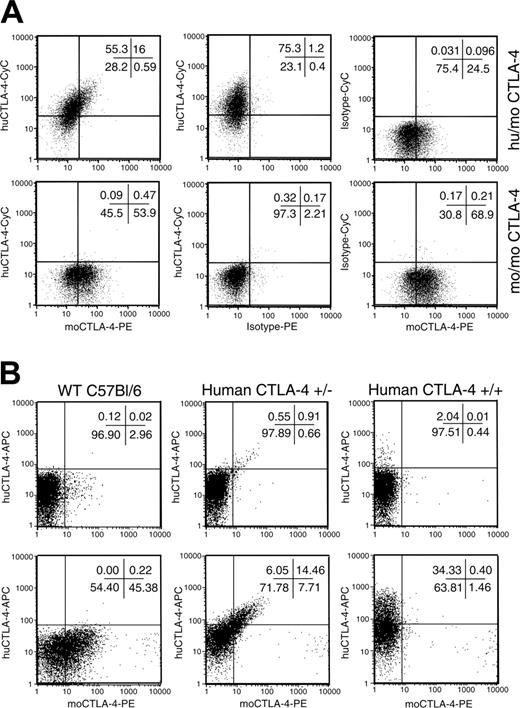

Codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 protein by T cells from human CTLA-4 knock-in heterozygotes. (A) Codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 in T cells after antigen stimulation. Spleen cells from human CTLA-4+/–×P1CTL F1 mice were stimulated for 66 hours in vitro with 0.1 μg/mL P1A peptide. Cells were harvested and stained for cell surface mouse CD3, followed by intracellular mouse and human CTLA-4. The top left panel shows the codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 protein on the same cells as indicated by the diagonal staining pattern. Non–knock-out littermates demonstrated a complete lack of human CTLA-4 expression (bottom left panel). Middle and right panels show isotype controls for each intracellular antibody. All profiles represent cells within the CD3+ gate. The same staining pattern has been observed with anti-CD3 mAb–stimulated T cells (K.M., unpublished observations). (B) Expression of mouse and human CTLA-4 molecules in unstimulated spleen CD4 T cells. Spleen cells from WT (CTLA-4 mo/mo), homozygous (human CTLA4+/+) and heterozygous (human CTLA4+/–) mice were surfaced-stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 and then stained for intracellular mouse and human CTLA-4 protein. Data shown were gated CD4+CD25– (top panels) and CD4+CD25+ subsets (bottom panels).

Codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 protein by T cells from human CTLA-4 knock-in heterozygotes. (A) Codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 in T cells after antigen stimulation. Spleen cells from human CTLA-4+/–×P1CTL F1 mice were stimulated for 66 hours in vitro with 0.1 μg/mL P1A peptide. Cells were harvested and stained for cell surface mouse CD3, followed by intracellular mouse and human CTLA-4. The top left panel shows the codominant expression of human and mouse CTLA-4 protein on the same cells as indicated by the diagonal staining pattern. Non–knock-out littermates demonstrated a complete lack of human CTLA-4 expression (bottom left panel). Middle and right panels show isotype controls for each intracellular antibody. All profiles represent cells within the CD3+ gate. The same staining pattern has been observed with anti-CD3 mAb–stimulated T cells (K.M., unpublished observations). (B) Expression of mouse and human CTLA-4 molecules in unstimulated spleen CD4 T cells. Spleen cells from WT (CTLA-4 mo/mo), homozygous (human CTLA4+/+) and heterozygous (human CTLA4+/–) mice were surfaced-stained with anti-CD4 and anti-CD25 and then stained for intracellular mouse and human CTLA-4 protein. Data shown were gated CD4+CD25– (top panels) and CD4+CD25+ subsets (bottom panels).

Functional replacement of mouse Ctla4 with the human CTLA4 gene in vivo. (A) Normal appearance of secondary lymphoid organs in 1-year-old homozygous human CTLA4 knock-in mice. (B) Normal expression of activation markers among spleen CD4 and CD8 T cells. Data shown are dot plots of gated CD8 (top panels) and CD4 (bottom panels) T cells.

Functional replacement of mouse Ctla4 with the human CTLA4 gene in vivo. (A) Normal appearance of secondary lymphoid organs in 1-year-old homozygous human CTLA4 knock-in mice. (B) Normal expression of activation markers among spleen CD4 and CD8 T cells. Data shown are dot plots of gated CD8 (top panels) and CD4 (bottom panels) T cells.

To determine whether human CTLA4 was properly expressed and spliced at the RNA level, spleen cells were obtained from human CTLA4+/– and human CTLA4+/+ C57BL/6 mice and stimulated with anti-CD3 (2C11) for 30 hours in culture. RNA was extracted from these cells and RT-PCR was performed with cDNA to amplify the full-length CTLA-4 sequence from exons 1 to 4. Primers spanning mouse exons 1 to 4 amplified a band of 648 base pairs. As shown in Figure 1D, the overwhelming majority of CTLA4 mRNA contained exons 1 to 4. In addition, by using primers specific for mouse and human CTLA-4, we were able to observe expression of both mouse and human CTLA4 alleles. As shown in Figure 1D, primers designed to amplify mouse Ctla4 exons 2 to 4 fail to produce a product in the homozygous knock-in mice, further confirming homologous recombination.

To determine whether human CTLA-4 protein was properly expressed, spleen cells from P1CTL+huCTLA4+/– and P1CTL+huCTLA4–/– littermate mice were stimulated in culture with P1A peptide for 66 hours. Cells were harvested and stained for both mouse and human intracellular CTLA-4 expression. As shown in Figure 2A (top panels), both mouse and human CTLA-4 proteins are detected in the human/mouse CTLA4 heterozygous mice. In addition, diagonal distribution of the human and mouse CTLA-4 molecules reveals that the 2 alleles are regulated by the same mechanism (top left). The specificity of the staining was confirmed by both isotype control staining as well as by the lack of binding of anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies in WT mo/mo littermates. To test whether the mouse and human CTLA4 alleles were similarly regulated in vivo, we analyzed freshly isolated spleen cells from WT mice or those that were either heterozygous or homozygous for the human CTLA4 alleles. It has been reported that the only subset that constitutively expresses CTLA4 in the peripheral lymphoid organs are the CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs).31 As shown in Figure 2B (bottom middle panel), among the Tregs diagonal distribution of human and mouse CTLA-4 proteins was observed in the heterozygous mice. As expected, homozygous knock-in mice did not express murine CTLA-4 protein. A minute non-Treg population in all 3 strains of mice expressed appreciable levels of CTLA-4 protein (top row). As with the Treg population observed in the heterozygous mice, these cells also expressed mouse and human CTLA-4 at similar levels as revealed by the diagonal distribution (Figure 2B, top middle panel).

CTLA4 knock-out mice are known to develop profound lymphoproliferative disorder and die within 4 weeks of birth.32 Our extensive observations have indicated that the homozygous human CTLA4 knock-in mice have a normal life span with no sign of autoimmune disease development over a period of observation longer than one year. As shown in Figure 3A, no enlargement of the lymphoid organs was observed in the human CTLA4 knock-in mice. Moreover, the extent of T-cell activation in vivo was essentially the same as that observed with WT T cells (Figure 3B). Therefore, the human CTLA-4 allele has functionally replaced the mouse CTLA-4 gene. As such, the knock-in mice may be used to study antibodies targeting the human CTLA-4 molecule in vivo.

Anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies with different potency in delaying tumor growth. (A) Growth kinetics of MC38 tumors in minimal disease model. CTLA-4 (hu/hu) mice were challenged with MC38 (5 × 105/mouse) in the lower abdomen. Two days later, the mice received either control mouse IgG or anti–CTLA-4 antibodies K4G4, L1B11, or L3D10 and the tumors were measured every 3 to 4 days. Data shown represent means and standard error of the mean (SEM) of tumor volumes until day 55, when some mice in antibody-treated groups reached their tumor burden end point (n=4). (B) Log transformation of tumor volume. The tumor growth over time was analyzed using the StataR XTGEE (cross-sectional generalized estimating equations) model. Six tests were done to compare the exponential slopes. All mAbs significantly delayed the growth kinetics of tumors (P < .001). In addition, significant delay of tumor growth was observed in mice that received L3D10 in comparison to those that received either L1B11 or K4G4 (P < .001). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received either control IgG or one of the anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. Complete rejection of tumors was observed in 2 of 9 mice in the L3D10-treated group. A log-rank test revealed that the 3 mAbs significantly prolonged mouse survival (P < .001–P = .004). Data shown in panels A and B are representative of those from 2 independent experiments. Data in panel C involve 8 to 9 mice per group.

Anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies with different potency in delaying tumor growth. (A) Growth kinetics of MC38 tumors in minimal disease model. CTLA-4 (hu/hu) mice were challenged with MC38 (5 × 105/mouse) in the lower abdomen. Two days later, the mice received either control mouse IgG or anti–CTLA-4 antibodies K4G4, L1B11, or L3D10 and the tumors were measured every 3 to 4 days. Data shown represent means and standard error of the mean (SEM) of tumor volumes until day 55, when some mice in antibody-treated groups reached their tumor burden end point (n=4). (B) Log transformation of tumor volume. The tumor growth over time was analyzed using the StataR XTGEE (cross-sectional generalized estimating equations) model. Six tests were done to compare the exponential slopes. All mAbs significantly delayed the growth kinetics of tumors (P < .001). In addition, significant delay of tumor growth was observed in mice that received L3D10 in comparison to those that received either L1B11 or K4G4 (P < .001). (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received either control IgG or one of the anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. Complete rejection of tumors was observed in 2 of 9 mice in the L3D10-treated group. A log-rank test revealed that the 3 mAbs significantly prolonged mouse survival (P < .001–P = .004). Data shown in panels A and B are representative of those from 2 independent experiments. Data in panel C involve 8 to 9 mice per group.

The human CTLA4 knock-in mice discriminate therapeutic effects of anti–CTLA-4 antibodies with essentially identical affinity and isotype

We have recently described a panel of anti–human CTLA-4 antibodies that promote expansion of human T cells in the human PBL-SCID mouse model. Moreover, the antibody-treated mice survived longer than the control Ig–treated mice.23 To test whether human CTLA4 knock-in mice are useful in discriminating the therapeutic effect of the anti–CTLA-4 antibodies, we injected colon cancer cell line MC38 subcutaneously into the CTLA4 knock-in mice. Two days later, the tumor cell–bearing mice received either control IgG or 1 of 3 isotype-matched anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. Among them, L3D10 and K4G4 have the same affinity and binding kinetics, whereas L1B11 has approximately 3-fold lower affinity. As shown in Figure 4A, all 3 antibodies demonstrated a statistically significant delay in tumor growth compared with mouse IgG control antibody. In addition, L3D10 proved to be the most potent antibody when compared with the other 2 treatment antibodies (Figure 4A-B). As seen in Figure 4C, all 3 antibodies led to enhanced survival compared with control Ig–treated mice. A survival advantage of L3D10-treated mice was also observed over those treated with L1B11 and K4G4 (Figure 4C).

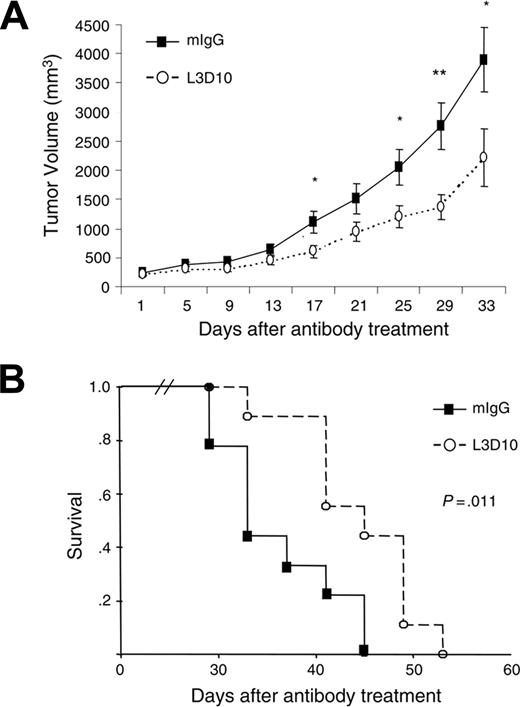

L3D10 treatment delays growth of established tumors in human CTLA-4 knock-in mice. MC38 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into the human CTLA-4 knock-in mice. At 10 to 14 days after tumor injection, when the tumors reached a mean diameter of 8 mm, the mice were injected with either L3D10 or control Ig every 4 days for 4 weeks. (A) Growth kinetics of established tumors in mice treated with either control IgG or L3D10 (n = 9). Data shown are means and SEM of tumor volumes. The volumes of large holes caused by necrosis in some mice were subtracted. Student t tests were used to compare the tumor size at each time point; those with P < .05 are indicated with an asterisk (*), whereas those with P < .01 are indicated with 2 asterisks (**). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received control IgG or L3D10. A log-rank test revealed that L3D10 significantly prolonged mouse survival (P = .011).

L3D10 treatment delays growth of established tumors in human CTLA-4 knock-in mice. MC38 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into the human CTLA-4 knock-in mice. At 10 to 14 days after tumor injection, when the tumors reached a mean diameter of 8 mm, the mice were injected with either L3D10 or control Ig every 4 days for 4 weeks. (A) Growth kinetics of established tumors in mice treated with either control IgG or L3D10 (n = 9). Data shown are means and SEM of tumor volumes. The volumes of large holes caused by necrosis in some mice were subtracted. Student t tests were used to compare the tumor size at each time point; those with P < .05 are indicated with an asterisk (*), whereas those with P < .01 are indicated with 2 asterisks (**). (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of mice that received control IgG or L3D10. A log-rank test revealed that L3D10 significantly prolonged mouse survival (P = .011).

To explore the therapeutic potential of the L3D10 antibody for large established tumors, we delayed treatment until approximately 2 weeks after tumor cell challenge. As shown in Figure 5, in comparison to the control Ig–treated group, the L3D10 antibody delayed tumor growth, and prolonged survival of tumor-bearing mice. Nevertheless, it should be noted that L3D10 alone did not cause complete tumor rejection. Therefore, it is likely that even the most efficient anti–CTLA-4 antibody will need to be used in combination with other reagents in order to achieve complete rejection of established tumors.

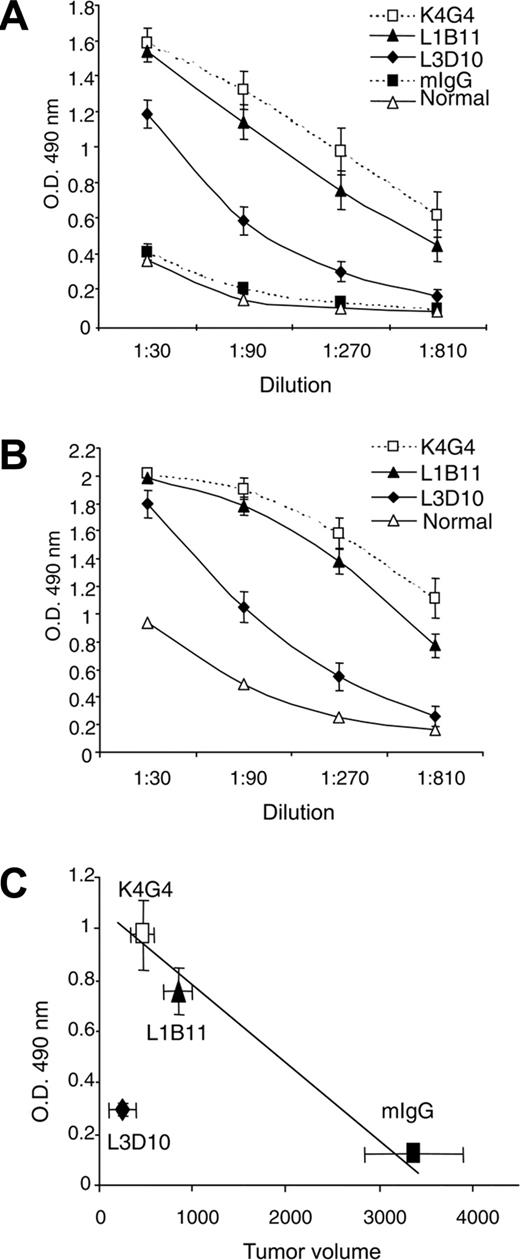

The human CTLA-4 knock-in mice unravel the link between cancer immunity and autoimmunity

Given the tendency of anti–CTLA-4 antibodies to exacerbate autoimmune diseases in experimental autoimmune models, it is of interest to determine whether the autoimmune side effects quantitatively correlate with antitumor immunity. Our analysis revealed that in wild-type mice, anti–mouse CTLA-4 antibody 4F10 suppressed tumor growth, but enhanced anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies. In contrast, anti–4-1BB antibody 2A induced cancer immunity without triggering anti-DNA antibody response (Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figure link at the top of the online article). Thus, the anti-DNA antibodies can serve as a useful marker for autoimmunity associated with anti–CTLA-4 antibody. We first compared mice treated with 3 different anti–CTLA-4 antibodies for their production of anti–double-stranded (ds) DNA antibodies. As shown in Figure 6A-B, although anti-dsDNA antibodies were detected in all tumor-bearing mice treated with anti–CTLA-4 antibodies, the mice that received K4G4 and L1B11 had 3- to 5-fold higher levels of anti-dsDNA antibodies than mice treated with L3D10. The difference was stable over the course of the treatment. Consistent with this variability in anti-dsDNA antibody induction, we observed more IgG deposition in kidney glomeruli of K4G4, L1B11-treated mice than in those treated with L3D10 (Table 1).

Incidence of antibody and complement C3 deposition in kidney glomeruli

Frozen sections of kidney were analyzed after the mice were killed (ie, when the mice reached early removal criteria [tumors of 4000 m3]), with the exception of 2 mice in the L3D10-treated group, in whom tumors never met the criteria for early removal.

The incidence of IgG deposition in mice treated with K4G4 (P = .029) and L1B11 (P = .029), but not L3D10 (P = .47), is significantly higher than in the control group.

A comparison between the amounts of the anti-dsDNA antibody and the sizes of the tumors suggests that for mice that received control Ig, L1B11, or K4G4, tumor size correlated inversely with the amount of anti-dsDNA antibodies. This observation suggests that, among these 3 groups, the intensity of the antitumor immune response correlates with that of the anti-DNA antibody response (Figure 6C). However, the group that received L3D10 treatment had the smallest tumor size with the lowest anti-dsDNA antibody levels. Thus, stronger cancer immunity does not have to be coupled with more severe autoimmune side effects.

Autoimmune side effects associated with different anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. Serum samples from mice that received anti–CTLA-4 treatment, as detailed in the Figure 2 legend, were collected on day 30 (A) and day 55 (B) and tested for anti-dsDNA antibodies. Data shown are means and standard deviations (SDs) of OD at 490. (C) Correlation between tumor growth suppression and anti-DNA antibodies in control IgG, L1B11, and K4G4, but not in L3D10-treated mice. Data shown are the means and SEM of tumor sizes and OD 490 of ELISA test using a 1:270 dilution of sera from tumor-bearing mice. Tumor size and anti-DNA antibody levels reflect data collected at 30 days after tumor challenge. The relative strength of anticancer immunity and autoimmunity has been repeated in 2 independent experiments involving 8 to 9 mice per group.

Autoimmune side effects associated with different anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. Serum samples from mice that received anti–CTLA-4 treatment, as detailed in the Figure 2 legend, were collected on day 30 (A) and day 55 (B) and tested for anti-dsDNA antibodies. Data shown are means and standard deviations (SDs) of OD at 490. (C) Correlation between tumor growth suppression and anti-DNA antibodies in control IgG, L1B11, and K4G4, but not in L3D10-treated mice. Data shown are the means and SEM of tumor sizes and OD 490 of ELISA test using a 1:270 dilution of sera from tumor-bearing mice. Tumor size and anti-DNA antibody levels reflect data collected at 30 days after tumor challenge. The relative strength of anticancer immunity and autoimmunity has been repeated in 2 independent experiments involving 8 to 9 mice per group.

Anti–CTLA-4 antibodies that induce different potencies in antitumor and autoimmune response bind to an overlapping site on CTLA-4

As measured by Biacore, L3D10 and K4G4 have essentially identical affinity for human CTLA-4.23 In addition, these antibodies have identical isotypes (IgG1, κ). To determine whether the antibodies have overlapping binding sites, we tested whether they compete with each other in binding to human CTLA-4. As shown in Figure 7A-C, all 3 antibodies cross-blocked each other's binding to CTLA-4, with efficiency that grossly correlates with their affinity to CTLA-4.23 Moreover, all antibodies were capable of blocking the binding of CTLA-4 to its natural ligand B7-1 (Figure 7D). The similarity of the immunochemical properties of these antibodies highlights the need for preclinical models to screen for anti–CTLA-4 antibodies with favorable therapeutic activity and acceptable autoimmune side effects.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that human CTLA-4 gene knock-in mice can serve as a valuable model for the preclinical screening of cancer therapeutic antibodies targeting the human CTLA-4 protein. The utility of this approach is based on 3 factors. First, human CTLA-4 has natural ligands in the mouse, as previously reported.9,24,33,34 Second, the signaling pathways used by mouse and human CTLA-4 are similar. Although this is difficult to verify because the mechanism of signal transduction for CTLA-4 is still unclear, the fact that the cytoplasmic domain of mouse and human CTLA-4 is 100% identical8 suggests that the signaling pathway is likely the same. Third and most importantly, human and mouse CTLA-4 must have the same biologic function. In support of this notion, we have demonstrated that the homozygous knock-in mice do not develop lethal autoimmune diseases, which were observed in the CTLA-4 knock-out mice.32 At the same time, polymorphisms of both mouse and human CTLA-4 genes affect genetic susceptibility to autoimmune diseases.35

Anti–CTLA-4 antibodies with distinct antitumor and autoimmune effects bound to an overlapping site on CTLA-4 and blocked B7-1/CTLA-4 interaction. (A-C) Cross-competition. Unlabeled anti–CTLA-4 antibody (100 μg/mL) was added to plates coated with CTLA-4 Ig. Given concentration of the biotinylated antibodies were added to the wells after 10 minutes. The amounts of biotinylated antibodies bound were determined by adsorption of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–labeled streptavidin to the plates. Data shown are means and SEM of OD 490. (D) All anti–CTLA-4 antibodies used in the study block B7-1–CTLA-4 interaction. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with human B7-1 were incubated with a mixture of CTLA-4 Ig and given anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. After washing away the unbound antibodies, the binding of CTLA-4 Ig was determined by flow cytometry using APC-labeled goat anti–human CTLA-4 antibody. Data shown are histograms depicting CTLA-4 Ig binding to human B7-1–transfected CHO cells. Frozen sections of kidney were analyzed after the mice were euthanized, when they reached early removal criteria (tumors reach 4000 mm3), with the exception of 2 mice in the L3D10-treated group in which tumors never reached the criteria for early removal. The incidences of IgG deposition in mice treated with K4G4 (P = .029) and L1B11 (P = .029), but not L3D10 (P = .47) are significantly higher than the control group.

Anti–CTLA-4 antibodies with distinct antitumor and autoimmune effects bound to an overlapping site on CTLA-4 and blocked B7-1/CTLA-4 interaction. (A-C) Cross-competition. Unlabeled anti–CTLA-4 antibody (100 μg/mL) was added to plates coated with CTLA-4 Ig. Given concentration of the biotinylated antibodies were added to the wells after 10 minutes. The amounts of biotinylated antibodies bound were determined by adsorption of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–labeled streptavidin to the plates. Data shown are means and SEM of OD 490. (D) All anti–CTLA-4 antibodies used in the study block B7-1–CTLA-4 interaction. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells transfected with human B7-1 were incubated with a mixture of CTLA-4 Ig and given anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. After washing away the unbound antibodies, the binding of CTLA-4 Ig was determined by flow cytometry using APC-labeled goat anti–human CTLA-4 antibody. Data shown are histograms depicting CTLA-4 Ig binding to human B7-1–transfected CHO cells. Frozen sections of kidney were analyzed after the mice were euthanized, when they reached early removal criteria (tumors reach 4000 mm3), with the exception of 2 mice in the L3D10-treated group in which tumors never reached the criteria for early removal. The incidences of IgG deposition in mice treated with K4G4 (P = .029) and L1B11 (P = .029), but not L3D10 (P = .47) are significantly higher than the control group.

Previously, we used the hu-PBL-SCID mouse model to explore the potential efficacy of anti–CTLA-4 antibody treatment.23 In this model, SCID mice are reconstituted with human peripheral blood, thereby creating a functional human immune system. Although this model is useful in screening antibodies for their potential anticancer effect, it is somewhat limited in evaluating other clinical parameters such as autoimmunity. By comparison, huCTLA-4 gene knock-in mice offer several important advantages, foremost of which is the fact that the immune response takes place in a natural setting. In contrast to knock-in mice, SCID animals require significant intervention to promote and maintain responses. Indeed, in the SCID model human T-cell survival is predicated on repeated injections of anti–natural killer (NK) cell antibodies as well as cytokines such as granulocyte macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). These factors must be taken into consideration when the therapeutic effects are interpreted. Nevertheless, it is of interest to note that in both models L3D10 treatment led to the most efficacious response. In the SCID model, mice undergoing L3D10 treatment exhibited the most substantial T-cell expansion, as well as the longest survival. Similarly, L3D10-treated huCTLA-4 knock-in mice displayed the most significant reduction in tumor growth among treatment groups, as well as the most enhanced survival benefit.

Perhaps the most important advantage with the knock-in model is our ability to evaluate autoimmune side effects associated with potential human therapeutic antibodies. A previous trial with a humanized anti–CTLA-4 antibody reported considerable side effects, with 43% of patients showing grades 3 to 4 autoimmune toxicity, including dermatitis, colitis/enterocolitis, hypophysitis, and hepatitis.20 In another trial, reactivity to melanocytes in skin and retina was associated with T-cell infiltration and necrosis in tumors.21 Autoimmune reactivity in anti–CTLA-4–treated mice has not been systematically analyzed, although depigmentation has been reported.14,36 Perhaps because of the relative short course of transplanted tumors, the autoimmune side effects in the mouse tumor model are relatively mild. However, a model that recapitulates autoimmune side effects will not only allow us to select antibodies with fewer side effects, but also to develop approaches to abrogate remaining side effects. In this regard, our quantitative comparison of the anti-dsDNA antibody titers and pathologic examination of tumor-bearing mouse kidney have revealed considerable heterogeneity among different antibodies in their autoimmune side effects. Surprisingly, L3D10, which induced the strongest therapeutic effect, provoked the least autoimmune side effects. The discordance between cancer immunity and autoimmunity reveals that autoimmune side effects and cancer therapeutic effects are not quantitatively linked. Such uncoupling provides a theoretical basis for selecting optimal anti–CTLA-4 antibodies or other therapeutic agents with the most desirable balance between cancer immunity and autoimmunity. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that our extensive search for pathologic changes, including blood chemistry and histologic examination of all major organs, has failed to reveal severe autoimmune diseases in tumor-bearing mice that can be attributed to anti–CTLA-4 antibodies (data not shown), which is different from experience with a clinical trial using a different anti–human CTLA-4 antibody.20

Several different mechanisms may be responsible for the differential effects of different anti–CTLA-4 antibodies. For instance, cancer immunity and autoimmunity may involve different effector cells. Alternatively, cancer targets and normal tissues may differ in their resistance to immune attack. In this context, previous studies by others have revealed that even when the antigen is shared between tumor and normal tissue, the antibody doses required for tumor rejection and autoimmune side effects differ.37-39 Regardless of the immunologic basis, the uncoupling of the quantitative link between autoimmunity and cancer immunity demonstrated here suggests that autoimmunity may not be a necessary price for cancer immunity. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the selective modulation of cancer immunity over autoimmunity.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, July 21, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2298.

Supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA58 033 [Y.L.], R41CA93 107, P01CA95 426) and a grant from the Department of Defense (DAMD 17-03-1-0013).

Y.L. and P.Z. are founders of OncoImmune, the recipient of grant R41CA93 107.

K.F.M. and K.D.L. contributed equally to this study.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank Lynde Shaw for secretarial assistance, and Jin Wen and Priya Joshi for antibody purification.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal