Abstract

CD4CD25+ regulatory T cells are fundamental to the maintenance of peripheral tolerance and have great therapeutic potential. However, efforts in this regard have been hampered by limiting cell numbers in vivo, an anergic phenotype in vitro, and a rudimentary understanding of the molecular basis for the functional state of CD4CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg cells). Here we show heterogeneity of suppressor activity among activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells and that, within this population, the functionally active, hyaluronan-binding form of CD44 (CD44act) is strikingly correlated with superior suppressor activity. Within 16 hours after in vitro activation, CD44act can discriminate enhanced suppressive function in in vitro proliferation assays and in an in vivo bone marrow engraftment model. The expression of other surface markers and that of Foxp3 are similar irrespective of hyaluronan binding and associated degree of suppressor potency. Furthermore, CD44act is induced on resting CD4CD25+ cells in vivo by allogeneic stimulation, with similar functional consequences. These results reveal a cell-surface marker that delineates functional activity within a population of activated CD4CD25+ regulatory T cells, thereby providing a potential tool for identifying regulatory activity and enriching for maximal suppressor potency.

Introduction

Among regulatory T cells with immunomodulatory properties, emphasis has recently focused on a population of CD4 T cells expressing the IL-2 receptor α chain (CD25).1,3 These cells have been shown to prevent autoimmune disease through their ability to maintain tolerance to self-antigens and to suppress proliferation and cytokine secretion by other cell types. Because CD4CD25+ regulatory T cells (Treg cells) develop early in the neonatal thymus and are exported to the periphery competent to suppress the activation of other self-reactive T cells, they are referred to as naturally occurring Treg cells.4,5

Activation and expansion of CD4CD25+ cells prolonged over one week in vitro or in vivo results in enhancement of their suppressor function.6,7 However, heterogeneity of function within a population of activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells has not been described, in part due to the absence of a marker that selectively discriminates such differential suppressor activity. The integrin αEβ7 has recently been described to distinguish potent suppressor activity independent of CD25 expression.8,9 Similarly, α4β1 and α4β7 distinguish differential suppressor populations within CD4CD25+ Treg cells in humans.10 The ability to enrich for potent activated Treg cells has been hampered by the ubiquitous expression of most known activation markers across T-cell populations. While many of these markers, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor (GITR), and lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), do distinguish Treg cells from unactivated nonregulatory T cells,11,15 they do not distinguish activated Treg cells from activated T effectors (Teff cells) nor, pertinent to the studies presented here, do they distinguish the degree of suppressor potency within a population of activated Treg cells.

Our laboratory has characterized a primary adhesion (rolling) interaction mediated by the activated form of CD44 (CD44act) on peripheral T cells interacting with its ligand hyaluronan (HA) on microvascular endothelium.16 We have established that the CD44-initiated adhesion pathway mediates specific T-cell egress during an immune response into an inflamed site,17 that microvascular endothelial cells respond to proinflammatory stimuli with the induction of elevated lumenal surface HA permitting capture,18 and that CD44act in conjunction with the integrin VLA-419,20 mediates the extravasation of activated T cells in vivo.17,18,20,21 CD44 has been implicated in a number of murine models of autoimmune disease,22,24 as well as in humans.25 These data support the hypothesis that CD44act is a significant participant in the well-described enhanced homing of activated T cells to inflamed tissues and suggest relevance of the CD44/HA interaction at target sites of autoimmunity.

While highly expressed, CD44 on resting lymphocytes is inactive and binds to HA only when conformationally activated.16,26,28 While the biochemical basis for CD44 activation in T cells is not clear, it does not require variant exon splicing.20,29 We have shown that in both mouse and human T cells, the activation of CD44 is achieved via physiologic triggering through the T-cell receptor (TCR) in vitro and in vivo.25,28 While CD44 is expressed at high levels and essentially uniformly on T cells with strong TCR stimuli, conversion to its activated form occurs only on a subset of activated T cells. These observations led us to examine T cells that are similar by other phenotypic criteria but that differ with respect to this unique marker.

Here we explore the significance of CD44act expression in naturally occurring Treg cells. We have examined the characteristics of CD4CD25+ cells induced to express CD44act and their behavior in vitro and in vivo. In contrast to the anergic properties of CD4CD25+ cells in vitro, including inability to flux calcium, proliferate, or secrete IL-2, we show that they have a striking capacity to up-regulate the ligand-binding form of CD44 compared with similarly treated CD4CD25– cells. Moreover, we establish that this marker is highly correlated with functional suppressor activity within activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells in both in vitro and in in vivo models. These results suggest that CD44act delineates a population containing highly potent suppressor activity identifiable with a simple surface stain and that this marker may aid in the tracking of such regulatory function over the course of immune and autoimmune responses. The results further imply utility in identifying and enriching for potent suppressors in strategies to deliver these cells therapeutically for control of dysregulated or pathologic immune responses.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Rooster comb sodium hyaluronate was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO) and fluoresceinated hyaluronan (Fl-HA) was prepared as described.16 OVA323-339 peptide was synthesized at UTSWMCD (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas).

Mice

Six- to 8-week-old Balb/c and C57BL/6 mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic mice were provided by Dr James Forman (UTSWMCD). DO11.10 TCR transgenic mice were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and used at 10 to 12 weeks. Experiments were conducted with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UTSWMCD.

Antibodies and cytokines

Purified biotin- and/or fluorochrome-conjugated antimouse antibodies were purchased from the following companies: CD3ϵ, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD28, CD44 (IM7), CD45RB, CD62L, CD69, CD90.2, CD152 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); anti–asialo GM1 (Wako, Richmond, VA); anti–mouse GITR (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); HA-blocking rat anti–mouse CD44 (KM81; ATCC, Manassas, VA). IL-2 was obtained from R&D Systems and IL-3, IL-6, and stem-cell factor (SCF) were from Biosource (Camarillo, CA).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained in PBS/5% FCS on ice with the exception of CTLA-4 surface staining, which was done at 37°C for 30 minutes. Analysis of stained cells was performed on a FACSCalibur using CellQuest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Cytokine analyses

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for IFNγ were carried out using QuantikineM Immunoassays (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

PCR analysis

Semiquantitative cytokine mRNA analysis. Total RNA was isolated from equal numbers of sorted cells using RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Reverse transcription was done on 0.5 to 1 μg of RNA using SuperScript First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Ten percent of resulting cDNA was used in multiplex polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for T-helper (TH1/TH2) cytokines (Biosource) and inflammatory cytokines (Maxim Biotech, South San Francisco, CA). Bands were resolved on 2% agarose gels.

Quantitative real-time PCR. The following primers and internal 6-FAM–labeled TaqMan probes were used (forward/reverse/probe): Foxp3, 5′-GGCCCTTCTCCAGGACAGA-3′/5′-GCTGAT-CATGGCTGGGTTGT-3′30 /5′-FAM-ACTTCATGCATCAGCTCTCCACTGTGGAT-BHQ-1–3′; TGFB1, 5′-CACTGATACGCCTGAGTG-3′/5′-GTGAGCGCTGAATCGAAA-3′/5′-FAM-CCGTCTCCTTGGTTCAGCCACTG-BHQ-1–3′; IL-10, 5′-CAGAGCCACATGCTCCTA-3′/5′-GGAGTCGGTTAGCAGTATG-3′/5′–FAM-CTGCGGACTGCCTTCAGCCAG–BHQ-1-3′; IFNG, 5′-AGC-AACAGCAAGGCGAAAAA-3′/5′-AGCTCATTGAATGCTTGGCG-3′/5′-FAM-ATTGCCAAGTTTGAGGTCAACAACCCACA–BHQ-1-3′; TNFA, 5′-CATCTTCTCAAAATTCGAGTGACAA-3′/5′-TGGGAGTAGACAAGGTACAACCC-3′/5′-FAM-CACGTCGTAGCAAACCACCAAGTGGA–BHQ-1-3′; HPRT (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase; internal reference31 ), 5′-CTGGTGAAAAGGACCTCTCG-3′/5′-TGAAGTACTCATTATAGTCAAGGGCA-3′/5′-FAM-TGTTGGATACAGGCCAGACTTTGTTGGATBHQ-1–3′. Amplifications were performed in 25 μL for 40 cycles on an MX3000P Real-Time PCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Expression of each mRNA was normalized to HPRT levels.

Cell separations

To isolate CD4CD25+ cells, CD4 or total T cells purified using CD4 or T-cell columns (R&D Systems) were incubated with anti-CD25–biotin in PBS/2% FCS, washed, incubated with anti-biotin microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), and separated according to the suggested protocol. Retained cells were eluted from the column and confirmed as at least 95% CD4CD25+ cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. For some experiments, CD4CD25+ cells were purified on a FACDiva Cell Sorter (BD Biosciences) using anti-CD25–PE plus anti-CD4–FITC. The resultant purity of sorted cells was greater than 98%. CD44hi/Fl-HA–positive (CD44act+) and CD44hi/Fl-HA–negative (CD44act–) cells were sorted using the FACDiva. Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) were prepared from T-depleted splenocytes, irradiated at 30 Gy, and plated at 5 × 104/well. Bone marrow cells for adoptive transfer were obtained by flushing femurs and tibias with PBS using a 23-gauge needle.

In vitro assays

Cultures were done in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. T cells were activated by incubating cells at 1 × 106 cells/mL in plates previously coated with anti-CD3 (5 μg/mL unless otherwise noted) plus anti-CD28 (5 μg/mL) or with 25 μM OVA323-339 peptide plus 1 × 106 irradiated APCs. For suppressor assays, 5 × 104 CD4CD25– T cells were cultured in triplicate in 96-well plates with 5 × 104 irradiated APCs plus 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 along with the indicated number of CD4CD25+ cells. Cultures were incubated for 72 hours, pulsed with 1 μCi/well (0.037 MBq/well) 3H-thymidine for the last 12 hours of culture, and counted.

In vivo transfer assays

All C57BL/6 or C57BL/6-Thy1.1 recipient mice received myeloablative doses of total body irradiation from a 137Cesium source (900-950 cGy) followed by intraperitoneal injection of 20 μg anti–asialo GM1. For suppression of reactivity in a graft-versus-host (GVH) model, CD4CD25– cells from Balb/c mice were labeled in 5 μm CFSE (5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Effectors (1 × 106) mixed with indicated numbers of unlabeled fresh unactivated CD4CD25+ cells or activated CD4CD25+ cells sorted on CD44act expression were injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6 hosts. Three days later, recipient mice were killed and cells in the peritoneal cavity of each mouse were harvested by lavage with 5 mL RPMI/2 mM EDTA, stained, and analyzed by FACS for CD25 on the proliferated responder population, as determined by decrease in CFSE intensity. Proliferation in the absence of suppressors over the assay did not result in the loss of CFSE-positive cells from the CFSE gate. To address potential differential migration or recovery, we performed controls in which pairs of Treg cells were labeled separately (PKH and CFSE) and coinjected intraperitoneally at 1:1 ratios. Mice were harvested at 72 hours and the ratio of PKH/CFSE cells in peritoneum was determined by FACS. For the most disparate pair (unactivated Treg cells/CD44act+ Treg cells), the final ratio at 72 hours was 1:1.1 (SD ± 0.04). Only negligible numbers of labeled cells were found in peripheral lymphoid organs.

For bone marrow (BM) hematopoietic stem-cell (HSC) experiments, 24 hours after irradiation C57BL/6 animals were reconstituted intravenously with 3 × 106 autologous bone marrow cells alone or together with 2 × 106 Balb/c CD4CD25– T cells as a source of allogeneic effectors. Some mice additionally received 1.5 × 106 Balb/c CD4CD25+ cells either freshly purified or in vitro activated and separated on the basis of CD44act expression. Five days after BM reconstitution, spleens were harvested, depleted of red blood cells, and plated (2 × 104 cells/35-mm dish in 1 mL Methocult M3234; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) with 10 ng/mL murine IL-3, 10 ng/mL murine IL-6, and 50 ng/mL murine SCF, for 5 to 7 days at 37°C. In vitro splenic colonies were counted manually using an inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY). Results are an average of at least 5 mice per group. To monitor trafficking efficiencies, CFSE-labeled CD4CD25– cells were mixed at equal ratios with CD4CD25+ cells (Balb/c, Thy1.2), either freshly isolated or in vitro activated and separated on the basis of CD44act expression, and injected intravenously into irradiated C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic recipients. Twenty hours after injection, spleens were harvested and the ratio of Treg cells to effectors within the Thy1.2+ gate was quantified by FACS. Results for each Treg cell + Teff cell combination were compared with those obtained in the fresh Treg cell + Teff cell group. Indexing to fresh Treg cell trafficking was accomplished by determining the average ratio of Treg cells/Teff cells for each group and dividing by the average ratio of fresh Treg cells/Teff cells. Localization to spleens was favored slightly by the CD44act– population by a 1:0.73 ratio (CD44act–/CD44act+).

To measure in vivo activation of CD4CD25+ Treg cells, 20 × 106 Balb/c CD4CD25+ Treg cell were injected intravenously into C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic recipients. After 72 hours, spleens were harvested and cells were stained with Thy1.2, Fl-HA, CD44, and CD25 for sorting on the basis of CD44act. Sorted in vivo–activated Treg cells and freshly purified unactivated CD4CD25+ cells were plated at varying numbers with 2.5 × 104 CD4CD25– responders plus irradiated APCs and 0.5 μg/mL anti-CD3 to measure suppressor activity.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons were done by Student t test, except where otherwise noted.

Results

CD44act as an activation marker that discriminates a subset within a larger population of activated T cells

The classic T-cell surface markers after activation include the acquisition of CD69 and CD25 and decreases of CD62L, TCR, and CD45RB. However, the naturally occurring CD4CD25+ subset constitutively expresses many of these activation markers shared with effector/memory cells.6,32 Therefore, we monitored temporal changes in activation markers on total naive CD4 T cells in conjunction with that of activated CD44 as assessed by staining with Fl-HA (Figure 1A). Using plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 stimulation, CD25 and CD69 are rapidly induced to maximal and uniform expression by 6 to 8 hours. At 24 hours, while T cells generally conform to a typical activated T-cell–staining profile of CD25+, CD69+, CD62Llo, TCRlo, only a relatively minor fraction of activated cells express CD44act (Figure 1A-B). We additionally used OVA323-339 TCR transgenic (DO11.10) naive CD4 T cells, thereby eliminating the diversity and variable affinity of the TCR. Again, only a similar limited fraction of cells respond with the expression of CD44act after 24 hours in vitro with high-dose OVA peptide–pulsed APCs (Figure 1C). Thus, the population of stimulated CD4 T cells distinguished by the functionally active form of CD44 represents only a fraction of cells otherwise fully activated by standard phenotypic criteria.

CD4CD25+ regulatory T cells have a pronounced capacity to up-regulate CD44act

To examine the regulation of CD44 activation on CD4CD25+ compared with CD4CD25– T cells, peripheral Balb/c CD4 cells were fractionated on the basis of CD25 expression. As anticipated, as an effector/memory marker, overall CD44 expression was slightly higher in the freshly isolated CD4CD25+ population than in corresponding CD4CD25– cells (Figure 2A). However, endogenous CD44act expression, as measured by anti-CD44 (KM81) blockable Fl-HA binding, was not detectable. Fractionated cells were activated for 24 hours at varying concentrations of anti-CD3 in the presence or absence of anti-CD28. Induction of CD69 increased in parallel in the 2 populations with increasing amounts of anti-CD3 both with and without anti-CD28 and was quantitatively similar (Figure 2B, top), as was the percentage of blasts (Figure 2B, middle). However, significantly increased expression in the CD4CD25+ cells in terms of CD44act expression is marked at all anti-CD3 concentrations (Figure 2B, bottom). This differential expression was not due to altered kinetics, since increased CD44act in the CD4CD25+ population was evident at all time points over a 3-day period (Figure 2C). Furthermore, while CD44act expression in the CD25– population peaks at approximately 30% by 48 hours and then declines, expression in the CD25+ population approaches 90% at 72 hours under these conditions. Representative FACS analyses comparing CD4CD25– to CD4CD25+ after 18-hour stimulation are shown in Figure 2C (bottom), where Fl-HA binding is 4-fold greater in the CD4CD25+ fraction. Thus, in contrast to their characteristically highly anergic behavior under these in vitro conditions,6,33 CD4CD25+ Treg cells are exceedingly prone to the functional activation of CD44 via TCR signaling.

Comparison of CD44act to other T-cell activation markers in total CD4 cells. (A) Naive peripheral lymph node T cells (1 × 106) were stimulated with 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28, harvested at 8 and 24 hours, and compared with unactivated cells (T = 0). Cells were stained as indicated in conjunction with Fl-HA for FACS. Conversion to CD44act is late relative to changes in other markers and occurs only on a fraction of cells. (B) Line graph representation of the changes over time in expression of CD44act compared with other indicated activation markers. (C) Two-color flow cytometric analysis of DO11.10 transgenic T cells stimulated for 24 hours with 25 μM OVA peptide plus APCs. Fl-HA staining was done with and without the HA-blocking anti-CD44 mAb, KM81.

Comparison of CD44act to other T-cell activation markers in total CD4 cells. (A) Naive peripheral lymph node T cells (1 × 106) were stimulated with 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28, harvested at 8 and 24 hours, and compared with unactivated cells (T = 0). Cells were stained as indicated in conjunction with Fl-HA for FACS. Conversion to CD44act is late relative to changes in other markers and occurs only on a fraction of cells. (B) Line graph representation of the changes over time in expression of CD44act compared with other indicated activation markers. (C) Two-color flow cytometric analysis of DO11.10 transgenic T cells stimulated for 24 hours with 25 μM OVA peptide plus APCs. Fl-HA staining was done with and without the HA-blocking anti-CD44 mAb, KM81.

CD44act is preferentially expressed on CD4CD25+ Treg cells after activation. (A) Absence of CD44act expression on resting CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– T cells. (B) Kinetics of activation marker expression on CD25+ and CD25– CD4 T cells. CD4 cells were separated into CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– fractions and activated at 1 × 106 cells/well with increasing concentrations of plate-bound anti-CD3 with (open) or without (closed) 5 μg/mL anti-CD28. The percentage of CD69+ cells (top) and blast-positive cells (by scatter, middle) are nearly indistinguishable between populations, whereas the percentage of Fl-HA–binding cells differs significantly between CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– for both treatments (bottom; P ≤ .01, Wilcoxon test). (C) CD44act expression on CD4CD25+ versus CD4CD25– cells after 18-, 42-, and 72-hour activation with 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28. Data shown are the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (*P ≤ .001; **P ≤ .01). FACS analyses from a representative experiment are shown below for the 18-hour time point with and without the HA-blocking anti-CD44 antibody, KM81.

CD44act is preferentially expressed on CD4CD25+ Treg cells after activation. (A) Absence of CD44act expression on resting CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– T cells. (B) Kinetics of activation marker expression on CD25+ and CD25– CD4 T cells. CD4 cells were separated into CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– fractions and activated at 1 × 106 cells/well with increasing concentrations of plate-bound anti-CD3 with (open) or without (closed) 5 μg/mL anti-CD28. The percentage of CD69+ cells (top) and blast-positive cells (by scatter, middle) are nearly indistinguishable between populations, whereas the percentage of Fl-HA–binding cells differs significantly between CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– for both treatments (bottom; P ≤ .01, Wilcoxon test). (C) CD44act expression on CD4CD25+ versus CD4CD25– cells after 18-, 42-, and 72-hour activation with 5 μg/mL plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28. Data shown are the mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments (*P ≤ .001; **P ≤ .01). FACS analyses from a representative experiment are shown below for the 18-hour time point with and without the HA-blocking anti-CD44 antibody, KM81.

Activated CD44 is associated with elevated expression of transcripts for relevant cytokines in CD4CD25+ Treg cells

It has been demonstrated that prior stimulation of CD4CD25+ regulatory cells improves their suppressor activity,33,34 and suppressor activity has been associated with preferential expression of particular cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10, and TGFβ.6,35 We therefore asked whether this marker discriminates cells with differential cytokine expression profiles. CD4CD25+ cells were stimulated for 16 to 18 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 to induce expression of CD44act, as in Figure 2. At this time the population is fully activated by the criteria of maximal CD69 expression. Cells were sorted into CD44hi HA-binding (CD44act) and CD44hi non–HA-binding fractions (Figure 3A) and directly lysed for comparison of cytokine mRNA expression by reverse transcriptase (RT)–PCR. The HA-binding fraction expressed markedly elevated mRNA levels for a number of cytokines, including those associated with suppression: IL-10, TGFβ, and IL-4 (Figure 3B). That mRNA for some proinflammatory cytokines is also expressed in these cells is consistent with previous literature,6,35 particularly given the strong TCR stimulus used, and was confirmed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Figure 3C). These results clearly indicate a skewing in transcript levels of many cytokines in the CD44act-bearing fraction of CD4CD25+ Treg cells, suggesting that this marker may in turn be associated with greater functional capacity.

CD44act expression on CD4CD25+ Treg cells is associated with elevated expression of relevant cytokine mRNA. (A) CD4CD25+ T cells were activated for 16 to 18 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 then sorted immediately on the basis of CD44act expression (gates indicated by boxes). (B) Sorted activated CD4CD25+ cells and freshly isolated, unactivated (Unact) CD4CD25+ cells were immediately lysed for multiplex RT-PCR to assess cytokine mRNA levels. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. Cycles for each cytokine: GMCSF, TNFα, 25 cycles; IL-13, IFNγ, TGFβ, 30 cycles; IL-4, -5, -10, 40 cycles. Internal control GAPDH was amplified for 25 cycles. (C) Relative cytokine mRNA levels as measured by real-time quantitative PCR analysis in CD44act+ and CD44act– fractions of CD4CD25+ cells activated for 24 hours and separated as in panel A. Cytokine levels in unactivated CD4CD25+ T cells are shown for comparison. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. *P ≤ .001 and **P ≤ .005 for comparisons of CD44act+ to CD44act– mRNAs.

CD44act expression on CD4CD25+ Treg cells is associated with elevated expression of relevant cytokine mRNA. (A) CD4CD25+ T cells were activated for 16 to 18 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 then sorted immediately on the basis of CD44act expression (gates indicated by boxes). (B) Sorted activated CD4CD25+ cells and freshly isolated, unactivated (Unact) CD4CD25+ cells were immediately lysed for multiplex RT-PCR to assess cytokine mRNA levels. Results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. Cycles for each cytokine: GMCSF, TNFα, 25 cycles; IL-13, IFNγ, TGFβ, 30 cycles; IL-4, -5, -10, 40 cycles. Internal control GAPDH was amplified for 25 cycles. (C) Relative cytokine mRNA levels as measured by real-time quantitative PCR analysis in CD44act+ and CD44act– fractions of CD4CD25+ cells activated for 24 hours and separated as in panel A. Cytokine levels in unactivated CD4CD25+ T cells are shown for comparison. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. *P ≤ .001 and **P ≤ .005 for comparisons of CD44act+ to CD44act– mRNAs.

CD44act on CD4CD25+ Treg cells distinguishes a population with highly enhanced suppressor activity in vitro

To address whether differential CD44act expression is associated with differential functional activity, CD4CD25+ cells were fully activated and fractionated as described in Figure 3 into HA-binding and non–HA-binding populations and placed in a standard anti-CD3 plus APC in vitro suppressor assay with CD4C25– T cells as responders. Activated CD44act+ CD4CD25+ cells suppressed proliferation more robustly than either activated CD44act– CD4CD25+ cells or freshly isolated unactivated CD4CD25+ cells (Figure 4A). We have observed an approximate 6-fold difference in the number of CD44act+ cells required to achieve 50% suppression compared with the CD44hi, non–HA-binding population and consistently a more than 10-fold difference compared with the direct ex vivo–isolated Treg cells (Figure 4B). The enhanced suppressor function of the CD44act-expressing population is particularly notable in view of the fact that when the non–HA-binding cells are returned to anti-CD3/APC stimulation in the suppressor assay, they continue to give rise to a significant percentage of new CD44act+ cells, albeit not as bright as in the original positive population (Figure 4C). Thus, at least some of the suppression observed in the CD44act– population potentially derives from the de novo generation of an HA-binding population within it.

CD44act marks a population of activated Treg cells with superior suppressor activity in vitro. (A) CD4CD25+ cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for 24 hours and sorted into CD44hi HA-binding (•) and CD44hi non–HA-binding (♦) populations, as in Figure 3. Suppressor activity of separated cells and fresh unactivated CD4CD25+ cells (▵) was determined by measuring the effect of graded numbers of Treg cells on proliferation of naive CD4CD25– cells. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. Statistical differences are shown between CD44act+ and CD44act– cells. *P < .005; **P ≤ .01. (B) The average number of unactivated, activated CD44act+, or activated CD44act– Treg cells required to give 50% suppression of proliferation. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. *P < .001 for all pairwise comparisons. (C) Regeneration during the course of a suppressor assay of cells expressing CD44act from a CD4CD25+ population previously depleted of such cells. After 24 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (left), cells were sorted into CD44act+ and CD44act– populations as shown (postsort analysis, middle). Sorted populations were PKH labeled and used in an in vitro suppressor assay. After 24 hours in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 plus APCs, cells were restained with CD44-allophycocyanin and Fl-HA and analyzed (right, PKH gated). Continued emergence of an HA-binding population from the originally CD44act– population is evident. (D) Generation of cells expressing CD44act from fresh, unactivated CD4CD25+ cells during the course of an in vitro suppressor assay. Cells were PKH labeled prior to assay. After 24 hours in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 plus APCs, cells were stained with CD44-allophycocyanin and Fl-HA and analyzed. PKH-gated cells contain a small KM81-blockable Fl-HA–binding population that was not present in the starting population. (E) Degree of suppression correlates with the percentage of CD44act+ cells in total activated CD4CD25+ cells. The numbers of cells required to give 90% suppression (calculated using the slopes of the lines for suppressor assays performed in triplicate with titrated numbers of Treg cells) and the percentage of CD44act+ cells in each population is shown. The number of CD44act+ cells within the total activated CD4CD25+ population (□) is approximately equal to the number of purified activated CD44act+ cells (▦) calculated to give 90% suppression in a representative experiment. Corrected value shown in hatched bar.

CD44act marks a population of activated Treg cells with superior suppressor activity in vitro. (A) CD4CD25+ cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for 24 hours and sorted into CD44hi HA-binding (•) and CD44hi non–HA-binding (♦) populations, as in Figure 3. Suppressor activity of separated cells and fresh unactivated CD4CD25+ cells (▵) was determined by measuring the effect of graded numbers of Treg cells on proliferation of naive CD4CD25– cells. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. Statistical differences are shown between CD44act+ and CD44act– cells. *P < .005; **P ≤ .01. (B) The average number of unactivated, activated CD44act+, or activated CD44act– Treg cells required to give 50% suppression of proliferation. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. *P < .001 for all pairwise comparisons. (C) Regeneration during the course of a suppressor assay of cells expressing CD44act from a CD4CD25+ population previously depleted of such cells. After 24 hours with plate-bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (left), cells were sorted into CD44act+ and CD44act– populations as shown (postsort analysis, middle). Sorted populations were PKH labeled and used in an in vitro suppressor assay. After 24 hours in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 plus APCs, cells were restained with CD44-allophycocyanin and Fl-HA and analyzed (right, PKH gated). Continued emergence of an HA-binding population from the originally CD44act– population is evident. (D) Generation of cells expressing CD44act from fresh, unactivated CD4CD25+ cells during the course of an in vitro suppressor assay. Cells were PKH labeled prior to assay. After 24 hours in the presence of soluble anti-CD3 plus APCs, cells were stained with CD44-allophycocyanin and Fl-HA and analyzed. PKH-gated cells contain a small KM81-blockable Fl-HA–binding population that was not present in the starting population. (E) Degree of suppression correlates with the percentage of CD44act+ cells in total activated CD4CD25+ cells. The numbers of cells required to give 90% suppression (calculated using the slopes of the lines for suppressor assays performed in triplicate with titrated numbers of Treg cells) and the percentage of CD44act+ cells in each population is shown. The number of CD44act+ cells within the total activated CD4CD25+ population (□) is approximately equal to the number of purified activated CD44act+ cells (▦) calculated to give 90% suppression in a representative experiment. Corrected value shown in hatched bar.

While unactivated Treg cells do not express CD44act initially (Figure 2A), a distinct portion of cells up-regulates this form after stimulation during a suppressor assay (Figure 4D). In addition, total activated Treg cells containing about half as many Fl-HA–binding cells as the sorted CD44act+ population (98% pure) require approximately twice as many cells to give 90% suppression compared with CD44act+ Treg cells (Figure 4E). The correspondence between the degree of suppression and the fraction of CD44act cells in the unmanipulated total population further indicates that the heightened suppressor function observed in the CD44act-enriched population is not due to direct signaling through HA during separation, as has been suggested by some studies for low–molecular-weight HA.36,37 These observations together substantiate a strong correlation between expression of this marker and functionally active Treg cells.

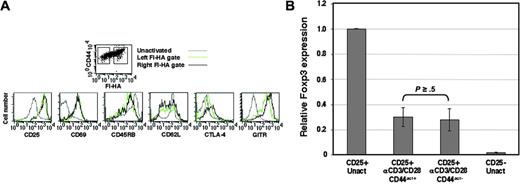

Activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells differing distinctly with respect to expression of CD44act do not show parallel differences for other activation markers

Since the CD4CD25+ population is known to bear increased effector/memory markers, it was of interest to determine whether differences in such surface markers correlated with activated Treg cells differing in expression of CD44act. CD4CD25+ cells were therefore stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for 24 hours, then stained for CD44, CD25, CD69, CD45RB, CD62L, CTLA-4, and GITR in combination with Fl-HA. Cells were gated on CD44+, Fl-HA–positive, and Fl-HA–negative populations as indicated and assessed for the other markers. As expected, activation resulted in increases in CD25, CD69, CTLA-4, and GITR, as well as decreases in CD62L and CD45RB compared with unactivated Treg cells (Figure 5A). However, except for slight shifts in CTLA-4 and GITR in the HA-binding population, all other markers were nearly indistinguishable between the HA-binding and HA-nonbinding subsets, providing additional evidence for the natural CD4CD25+ Treg cell phenotype of the entire population and the otherwise similar phenotypic state of activation of cells that differ with respect to CD44act expression. The magnitude difference seen in Fl-HA binding (Figure 5A, top) together with the functional data presented in Figure 4 suggests that among cell-surface activation markers, CD44act most clearly delineates functional activity among activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells.

Foxp3 transcript levels do not correlate with CD44act expression or degree of suppressor activity in activated Treg cells

As a highly characterized marker for this subset, Foxp3 has been shown to be expressed after in vitro activation of CD4CD25+ cells.38,41 However, prior studies have not addressed the extent to which the level of Foxp3 expression correlates with suppressor function. When mRNA from the activated CD4CD25+ populations fractionated on the basis of CD44act was examined by quantitative real-time PCR for Foxp3, levels were essentially equivalent (P ≥ .5; Figure 5B). Moreover, these results are consistent with previous reports of decreases in Foxp3 mRNA after stimulation of CD4CD25+ cells,31,38,39 although still much higher than the CD4CD25– cells (P ≤ .01 for both activated CD4CD25+ populations). These data serve to further confirm the suppressor phenotype of the CD44act– population and, together with cell-surface staining data, suggest that CD44act is a unique marker within the CD4CD25+ population that discriminates the degree of regulatory function.

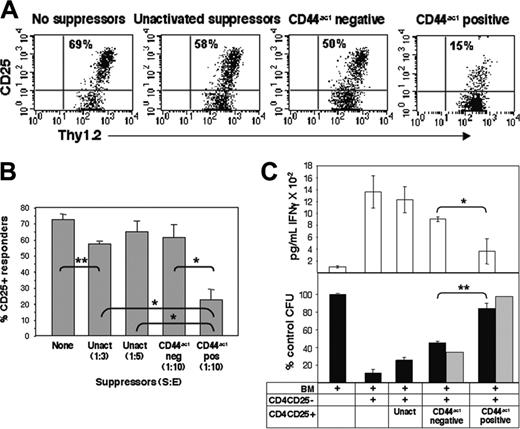

Transfer of CD4CD25+ Treg cells expressing activated CD44 results in enhanced regulatory activity in vivo

It has been previously shown that effector-cell activation and function, but often not proliferation, are suppressed by CD4CD25+ Treg cells in vivo.42,43 To assess the effect of suppressors on the activation of effector T cells in vivo, Balb/c CD4CD25– effector T cells were CFSE labeled and injected into C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic recipients together with various populations of unlabeled Balb/c CD4CD25+ Treg cells. Treg cells were first activated for 24 hours and separated into HA-binding and non–HA-binding populations, as described in Figure 3. These, or control freshly isolated unactivated Treg cells, were injected intraperitoneally along with CFSE-labeled effector cells. After 3 days, peritoneal cells were harvested and assessed for CD25 expression on dividing alloreactive cells as a measure of effector-cell activation in the CFSE/Thy1.2 compartment. Transfer of control autologous Balb/c CD4CD25– T cells showed no proliferation or CD25 up-regulation (not shown). Cotransfer of suppressor cells bearing CD44act did not affect proliferation of effectors but did significantly reduce their CD25 expression from 69% of CFSE-labeled cells in the presence of no suppressors to 15% in the presence of suppressors expressing CD44act, even at suppressor-effector (S/E) ratios of 1:10 (Figure 6A-B). In contrast, activated CD44hinon–HA-binding Treg cells exerted only quite modest effects on responder-cell activation. Freshly isolated suppressors likewise have little effect even at higher S/E ratios. Thus, Treg cells expressing CD44act exhibit pronounced suppressive activity in vivo, and this property is sustained over 72 hours.

Expression of markers associated with CD4CD25+ Treg cells is similar irrespective of CD44act levels after activation. (A) After 24-hour activation in vitro, cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating for histograms was done on the basis of Fl-HA binding, as indicated in the top panel. The HA-negative gate (left) is established based on the limits of KM81 blocking of the HA-positive population. Marker expression for total resting CD4CD25+ cells (gray line) is also shown for comparison. (B) Relative Foxp3 mRNA levels as measured by real-time quantitative PCR analysis in CD44act+ and CD44act– fractions of CD4CD25+ cells activated for 24 hours and separated as in Figure 3. Foxp3 levels in unactivated CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– T cells are shown for comparison. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. P = .003, comparing CD44act+ Treg cells to unactivated CD4CD25– cells; P = .007, comparing CD44act– Treg cells to unactivated CD4CD25– cells.

Expression of markers associated with CD4CD25+ Treg cells is similar irrespective of CD44act levels after activation. (A) After 24-hour activation in vitro, cells were stained and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating for histograms was done on the basis of Fl-HA binding, as indicated in the top panel. The HA-negative gate (left) is established based on the limits of KM81 blocking of the HA-positive population. Marker expression for total resting CD4CD25+ cells (gray line) is also shown for comparison. (B) Relative Foxp3 mRNA levels as measured by real-time quantitative PCR analysis in CD44act+ and CD44act– fractions of CD4CD25+ cells activated for 24 hours and separated as in Figure 3. Foxp3 levels in unactivated CD4CD25+ and CD4CD25– T cells are shown for comparison. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 3 experiments. P = .003, comparing CD44act+ Treg cells to unactivated CD4CD25– cells; P = .007, comparing CD44act– Treg cells to unactivated CD4CD25– cells.

An early and major target in GVH is the hematopoietic stem cell,44,46 and the CD4CD25+ Treg cell population can effectively impede GVH disease (GVHD) in murine models.47,49 We therefore investigated HSC rescue by Treg cells in a GVH model to obtain an early readout and thereby minimize CD44act– populations potentially recovering CD44act expression over time with further stimulation. Lethally irradiated C57Bl/6 mice were reconstituted with syngeneic bone marrow and coinjected with Balb/c CD4CD25– effector T cells with and without CD4CD25+ suppressor populations generated as described in Figure 3. After 5 days, splenic colony-forming units (CFUs) were measured in vitro as a reflection of HSC engraftment. Simultaneously, serum levels of IFNγ, typically elevated early in a GVH reaction,50,51 were measured. Syngeneic bone marrow engraftment alone gives rise to baseline numbers of CFUs (110 per 2 × 104 plated cells) and negligible levels of IFNγ (Figure 6C). CFUs are dramatically diminished with the addition of allogeneic CD4CD25– T effector cells. While the addition of freshly isolated Balb/c CD4CD25+ suppressors restores CFUs to about 20% of baseline, the suppressor population enriched for CD44act demonstrates the greatest rescue, with CFUs approaching BM reconstitution only, as well as the greatest normalization of IFNγ levels. Activated CD4CD25+ cells depleted of the HA-binding fraction (CD44act–) provide some rescue of HSC colonies, but activity is markedly inferior to that seen with the HA-binding cells. Moreover, when the effects of fractionated suppressors are adjusted for trafficking efficiency relative to fresh CD4CD25+ cells, the difference is yet more pronounced (Figure 6C, ▦). Thus, in these 2 in vivo models, the expression of CD44act on CD4CD25+ cells is highly preferentially associated with suppression of effector T-cell activation as well as with inhibition of manifestations of GVHD.

Treg cells expressing CD44act show an enhanced suppressive effect in alloreactive and GVH models in vivo. (A) C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic hosts were injected intraperitoneally with 1 × 106 CFSE-labeled Balb/c CD4CD25– T cells along with 2 × 105 unlabeled unactivated or 1 × 105 activated Balb/c CD4CD25+ cells sorted based on CD44act expression. After 3 days, cells in the peritoneum were collected by lavage and analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression of CD25 as a reflection of alloactivation of CFSE-gated CD4CD25– responder T cells is shown. Data are from individual mice and are representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) Average in vivo suppression of CD25 expression on T effectors in the presence of Treg cells. Transfers were conducted as in panel A. Experiments were done with 4 mice/group. Statistical comparison between relevant groups is shown. *P < .001; **P ≤ .002. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. (C) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were reconstituted with C57Bl/6 bone marrow cells (3 × 106) and simultaneously given 2 × 106 Balb/c CD4CD25– effector T cells together with 1.5 × 106 freshly isolated or CD44act fractionated CD4CD25+ regulatory cells as in panel A. On day 5, serum was collected for IFNγ measurement and 2 × 104 splenocytes were plated in Methocult M3234 plus stem-cell growth factors. Five to 7 days later, colonies were counted. The number of CFUs per plate is shown as a percentage of BM alone and is an average for at least 5 mice per group (bottom, ▪). The ▦ reflects the values when CFUs for fractionated cells are indexed for homing efficiency relative to freshly isolated, unactivated CD4CD25+ cells. IFNγ serum levels for each group are shown in the top panel. Statistical comparison between indicated groups is shown. *P ≤ .002; **P ≤ .01. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 5 experiments.

Treg cells expressing CD44act show an enhanced suppressive effect in alloreactive and GVH models in vivo. (A) C57BL/6-Thy1.1 congenic hosts were injected intraperitoneally with 1 × 106 CFSE-labeled Balb/c CD4CD25– T cells along with 2 × 105 unlabeled unactivated or 1 × 105 activated Balb/c CD4CD25+ cells sorted based on CD44act expression. After 3 days, cells in the peritoneum were collected by lavage and analyzed by flow cytometry. Expression of CD25 as a reflection of alloactivation of CFSE-gated CD4CD25– responder T cells is shown. Data are from individual mice and are representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) Average in vivo suppression of CD25 expression on T effectors in the presence of Treg cells. Transfers were conducted as in panel A. Experiments were done with 4 mice/group. Statistical comparison between relevant groups is shown. *P < .001; **P ≤ .002. Data are the mean ± SD of 4 experiments. (C) Lethally irradiated C57BL/6 mice were reconstituted with C57Bl/6 bone marrow cells (3 × 106) and simultaneously given 2 × 106 Balb/c CD4CD25– effector T cells together with 1.5 × 106 freshly isolated or CD44act fractionated CD4CD25+ regulatory cells as in panel A. On day 5, serum was collected for IFNγ measurement and 2 × 104 splenocytes were plated in Methocult M3234 plus stem-cell growth factors. Five to 7 days later, colonies were counted. The number of CFUs per plate is shown as a percentage of BM alone and is an average for at least 5 mice per group (bottom, ▪). The ▦ reflects the values when CFUs for fractionated cells are indexed for homing efficiency relative to freshly isolated, unactivated CD4CD25+ cells. IFNγ serum levels for each group are shown in the top panel. Statistical comparison between indicated groups is shown. *P ≤ .002; **P ≤ .01. Data shown are the mean ± SD of 5 experiments.

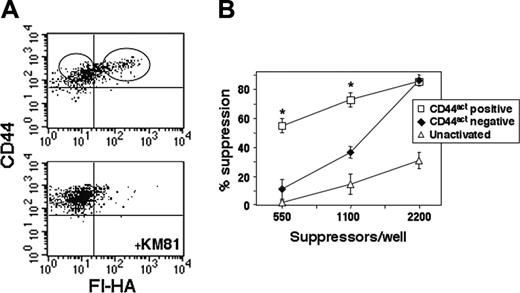

CD44act is up-regulated in vivo on CD4CD25+ T cells in response to alloantigen

The studies thus far have focused on the functional and phenotypic attributes of Treg cells expressing this marker after polyclonal activation in vitro. To determine whether CD44act is induced directly in vivo on the CD4CD25+ subset, Balb/c CD4CD25+ cells were isolated and immediately injected intravenously into irradiated C57Bl/6-Thy1.1 hosts to induce an alloreaction. After 72 hours, splenocytes were harvested; stained with Thy1.2-allophycocyanin, CD44-PE, and Fl-HA; and the donor CD4CD25+ cells were examined for HA binding. A clear KM81 blockable HA-binding population is evident within the Thy1.2+ gate, demonstrating that CD44act is indeed up-regulated in vivo as well as in vitro on these Treg cells with proper stimulation (Figure 7A) and further supporting a physiologic relevance for this marker. In addition, when these cells were sorted directly ex vivo on the basis of CD44act, then placed in an anti-CD3 suppression assay, superior activity was evident in the CD44act+ population (Figure 7B).

Discussion

A variety of cell-surface markers are available that together aid in identifying, isolating, and characterizing the heavily scrutinized CD4CD25+ regulatory T-cell subset. However, no surface marker capable of discriminating the degree of suppressor efficacy or potency within this compartment has been described. Like other markers of T-cell activation, CD44act is regulated as the result of physiologic interactions and signaling through the TCR.25,28 However, unlike these other markers, conversion to the activated form of CD44 is relatively late and is expressed only on a subpopulation of T cells under conditions of full T-cell activation. Because of their general anergic characteristics and a molecular profile enriched in genes antagonistic to cellular signaling,7,13 our expectation was that the CD4CD25+ population would be refractory to the induction of CD44act. To the contrary, we found these cells highly prone to the expression of this activation marker compared with their CD25– counterparts. Further examination revealed a strong association between the expression of CD44act and degree of suppressor activity. This correlation distinguishes not only suppressor potency between resting and activated CD4CD25+ Treg cells but also among activated Treg cells that appear otherwise phenotypically similar. The results emphasize the physiologic relevance of this marker and its potential for monitoring and isolation of suppressor activity directly ex vivo.

The naturally occurring CD4CD25+ subset constitutively expresses several surface markers characteristic of memory T cells.32 Moreover, on prolonged activation and expansion of these cells there have been reported shifts in expression of several memory/effector activation markers, in agreement with the results shown here (Figure 5A). However, we show that these surface markers are not substantially different when comparing activated Treg cells that differ by nearly a log in CD44-dependent Fl-HA binding, and therefore do not carry the same functional implications. The forkhead/winged helix transcription factor Foxp3 is thought to program the development and function of the CD4CD25+ subset and has proven useful in their identification.31,38,52,54 However, the degree to which suppressor function correlates with Foxp3 mRNA levels among activated Treg cells has not been directly addressed, and reports have generally described down-regulation of Foxp3 mRNA on activation.31,38,40 The use of CD44act to separate activated Treg cells with differential suppressor function allowed us to determine that Foxp3 transcript levels do not differ between the subpopulations defined by this marker (Figure 5B).

Conversion of CD44 to its active form occurs on Treg cells in vivo and is associated with increased suppressor function. (A) C57Bl/6-Thy1.1 congenic hosts were injected intravenously with 20 × 106 freshly isolated Balb/c CD4CD25+ T cells (Thy1.2). After 72 hours, spleen cells were stained with Thy1.2-allophycocyanin, CD44-PE, and Fl-HA. Fl-HA/CD44 staining of cells gated on Thy1.2 is shown with and without KM81 blocking. (B) CD44act– and CD44act+ fractions in the Thy1.2 gate were sorted as shown and placed in an in vitro anti-CD3 suppressor assay with 2.5 × 104 CD4CD25– responders. Suppressor activity (mean ± SEM for 2 experiments) is significantly enhanced in the in vivo arising CD44act+ population. *Statistical comparison of CD44act+ to CD44act– and to unactivated Treg cell groups. P ≤ .001 for both pairwise comparisons.

Conversion of CD44 to its active form occurs on Treg cells in vivo and is associated with increased suppressor function. (A) C57Bl/6-Thy1.1 congenic hosts were injected intravenously with 20 × 106 freshly isolated Balb/c CD4CD25+ T cells (Thy1.2). After 72 hours, spleen cells were stained with Thy1.2-allophycocyanin, CD44-PE, and Fl-HA. Fl-HA/CD44 staining of cells gated on Thy1.2 is shown with and without KM81 blocking. (B) CD44act– and CD44act+ fractions in the Thy1.2 gate were sorted as shown and placed in an in vitro anti-CD3 suppressor assay with 2.5 × 104 CD4CD25– responders. Suppressor activity (mean ± SEM for 2 experiments) is significantly enhanced in the in vivo arising CD44act+ population. *Statistical comparison of CD44act+ to CD44act– and to unactivated Treg cell groups. P ≤ .001 for both pairwise comparisons.

While the association of CD44act with Treg cell function is clear from these studies, the degree to which it is obligatory for function is more difficult to determine. Preliminary antibody-blocking experiments suggest that CD44act ligand binding function is not directly involved in suppression. Since CD44act-expressing Treg cells are highly activated, it is conceivable that elevated CD25 expression and resulting IL-2 consumption could be responsible for increased suppression. However, CD44actlow activated Treg cells express similar levels of CD25 (Figure 5B) yet suppress less effectively. Consistent with prior studies,6,33 CD44act Treg cells do not suppress across a semipermeable (Transwell) barrier, making this explanation unlikely (data not shown). Nonetheless, we cannot rule out that local IL-2 depletion occurs with close proximity to effectors. Moreover, increased costimulation and combinations of cytokines do not substantially improve the degree of conversion to CD44act-expressing cells (data not shown). Identifying a stable negative population under conditions of stimulation is made difficult by the continued emergence of CD44act on a portion of activated T cells after depletion of cells binding HA (Figure 4C). Thus, much of the suppressor activity detected in the CD44act– pool may be attributed to this de novo population. To the extent that is the case, functional activity would indeed be closely linked with expression of this marker. Consistent with this interpretation is the observation that freshly isolated Treg cells do up-regulate this marker both in vitro (Figure 4D) and in vivo (Figure 7A). Since our in vivo experiments show relative stability of these functional differences over time (Figures 6-7), by selecting the cells that have the greatest propensity to convert CD44, we may also be selecting the most “triggerable” and thus functionally active subset. The latter interpretation is supported by the fact that while CD44act emerges from a population depleted of such cells on restimulation, the intensity consistently remains lower than on the positive (Figure 4C).

The basis for the predilection of the CD4CD25+ subset to convert CD44 to its functionally activated form is not clear. The fact that this naturally occurring population is thought to have been selected on self-antigens in rigorous fashion and that, as a result, these cells have clear characteristics of memory T cells may be a contributing factor. However, CD4CD25– cells of memory phenotype isolated directly ex vivo do not show the same degree of CD44 activation as the CD25+ subset (data not shown). CD4CD25+ cells have also been reported to be more sensitive to antigen-induced activation in the presence of IL-2, at least in terms of proliferation,11 and TCR affinity has been shown to play a significant role in the development of the CD25+ subset.55 The inclination to up-regulate CD44act may reflect this and is consistent with a correlation between the expression of CD44act and a heightened state of TCR-mediated cellular activation. When considered in the context of CD44-initiated extravasation, it would be reasonable that a cell armed with a trafficking molecule should also be coordinately poised to execute effector function at the target site—that is, for CD4CD25+ T cells—to exert suppression.

Considerable recent effort has concentrated on the expansion of CD4CD25 Treg cells for controlling pathologic immune responses in the settings of autoimmune disease, transplantation, and GVHD. While anergic and hypoproliferative in vitro, it is clear that this proliferative deficit can be overcome with the addition of exogenous IL-26,33 and increased potency of suppressors is obtained after activation and expansion in vitro or in vivo.6,7,33 However, the 3- to 4-fold improvement in these studies was seen after 7-day activation, whereas in the studies presented here, increased suppression in the populations expressing CD44act was seen with less than 24-hour activation, with a more than 10-fold increase in suppressive function compared with resting cells. In models of GVH disease, amelioration of disease has been reported after expansion of cells in vitro,47,49,56 and initial attempts to expand alloreactive Treg cells in humans have shown promise.57 Treg cells from nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice can also be expanded in vitro and used therapeutically to protect in autoimmune situations, and autoantigen-specific CD4CD25+ cells were considerably more efficacious than polyclonally expanded counterparts.58 The observations provided by our studies have direct implications for these efforts: (1) the CD44act marker has the potential for preferentially selecting highly potent Treg cells very early after in vitro stimulation for subsequent expansion; (2) since cells bearing this marker can be detected in vivo under autoimmune circumstances25 (S.D., unpublished observations, July 2003), it may be feasible to directly isolate the Treg cells most relevant to the current autoimmune process (eg, islet-specific, in T1D), and therefore the most efficacious, on the basis of this marker. Importantly, there would be no requirement for prior knowledge of the autoantigen(s) in any autoimmune disease, as the selection itself would be antigen independent.

In conclusion, we have identified a preferentially expressed cell-surface marker demarcating a subset of CD4CD25+ T cells with heightened activation status and functionally primed for enhanced suppression. A significant implication of the CD44act phenotype in the Treg cells compartment is that it may provide a tool to aid in monitoring and isolation of highly potent cells for therapeutic purposes and for furthering the understanding of the signaling pathways leading to suppressor function in this subset.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, September 22, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2277.

Supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; R01 HL56746, M.H.S.) and a Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (M.H.S.). M.F. is supported by an Integrative Immunology Training Grant from the NIH (5T32AI005284).

M.F. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and contributed to writing of the paper; S.D. performed research and analyzed data; P.E. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and M.H.S. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We gratefully acknowledge Bonnie Darnell and Angela Mobley for their invaluable assistance in cell sorting and Drs Michael Bennett and Nitin Karandikar for helpful discussions and manuscript review.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal