Abstract

The immunosuppressive drugs rapamycin and cyclosporin A (CsA) are widely used to prevent allograft rejection. Moreover, they were shown to be instrumental in experimental models of tolerance induction. However, it remains to be elucidated whether these drugs have an effect on the CD4+CD25+ regulatory T-cell (TREG) population, which plays an important role in allograft tolerance. Recently, we reported that alloantigen-driven expansion of human CD4+CD25+ TREGs gives rise to a distinct highly suppressive CD27+TREG subset next to a moderately suppressive CD27-TREG subset. In the current study we found that rapamycin and CsA do not interfere with the suppressive activity of human naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells. However, in contrast to CsA, rapamycin preserved the dominance of the potent CD27+TREG subset over the CD27-TREG subset after alloantigen-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs in vitro. Accordingly, CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin displayed much stronger suppressive capacity than CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of CsA. In addition, CD4+CD25+ TREG cells cultured in the presence of rapamycin, but not CsA, were able to suppress ongoing alloimmune responses. This differential effect of rapamycin and CsA on the CD27+TREG subset dominance may favor the use of rapamycin in tolerance-inducing strategies.

Introduction

The development of an alloimmune response into rejection or stable allograft tolerance is strongly determined by the balance between alloreactive effector cells and CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (TREGs).1,2 Currently used immunosuppressive drugs are efficient in preventing allograft rejection by reducing effector T-cell expansion. However, it remains to be elucidated whether these drugs antagonize the induction of tolerance by affecting the naturally occurring TREG population.

CD4+CD25+ TREGs exert their immunosuppressive effect after activation by T-cell receptor (TCR) triggering.3 Moreover, it has recently been demonstrated that signaling through the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor is crucial for the functional activity of TREGs.4,5 Cyclosporine A (CsA) inhibits TCR-mediated activation and IL-2 production, whereas rapamycin blocks intracellular signaling in response to T-cell growth factors like IL-2.6,7 It can therefore be expected that CsA and rapamycin have different effects on the function of CD4+CD25+ TREGs. Indeed, calcineurin inhibition by CsA may impair the development and function of TREGs, whereas rapamycin was found to favor CD4+CD25+ T-cell–dependent immunoregulation in vitro and in vivo.8-12

Recently, we reported that allogeneic expansion of human naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ TREGs leads to the emergence of a distinct, highly suppressive CD27+TREG subset next to a CD27-TREG subset.13 These CD27+TREG and CD27-TREG subsets displayed a 50% inhibition of in vitro responses at ratios of 1:500 and 1:50, respectively, and were further distinguished by distinct growth characteristics and phenotype. The CD27+TREG subset was shown to suppress not only naive and antigen-experienced memory T cells but also ongoing T-cell responses. In line with our findings, CD4+CD25+CD27+ TREGs were identified as a potent regulatory subset in cord blood and in a large-scale in vitro expansion system.14,15 In addition, the combined expression of CD25 and CD27 allowed the differentiation of highly suppressive FoxP3+ regulatory T cells from activated effector T cells in synovial fluid of patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.16 It can be envisaged that the strong regulatory capacity of CD27+TREG may be of value in promoting stable allograft tolerance.

Here, we describe that both CsA and rapamycin permit the activation of the naturally occurring regulatory CD4+CD25+ TREG. However, rapamycin fosters the dominance of CD27+TREG over CD27-TREG after expansion of the CD4+CD25+ TREG pool on allogeneic activation, whereas expansion in the presence of CsA tips the balance in favor of CD27-TREG. The high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio, as preserved by rapamycin, benefits the suppressive capacity of the CD4+CD25+ TREG pool as a whole. Moreover, although TREGs cultured in the presence of either CsA or rapamycin are able to suppress naive T-cell responses, only TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin can suppress ongoing T-cell responses. We thus propose that rapamycin promotes the induction of allograft tolerance by preserving a beneficial CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio.

Materials and methods

The protocols of this study were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. Voluntary blood donors gave written informed consent.

Isolation of cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation (Lymphoprep; Nycomed Pharma, Oslo, Norway) of buffy-coats obtained from healthy donors. CD4+ T cells were purified from PBMCs by negative selection using monoclonal antibodies (mAb's) directed against CD8 (RPA-T8), CD14 (M5E2), CD16 (3G8), CD19 (4G7), CD33 (P67.6), CD56 (B159), and CD235 (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium) combined with sheep anti–mouse IgG–coated magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway). This resulted in a CD4+ T-cell purity of greater than 95% and the absence of CD8+ T cells. From purified CD4+ T cells, naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells were isolated using the magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) CD25+ magnetic microbead method (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), using half the amount of beads recommended by the manufacturer. CD4+CD25+ T cells were immediately used after isolation, and all other cell types were used either fresh or on thawing of liquid nitrogen–stored cell stocks. HLA typing was conducted according to ASHI (American Society for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics) standards and largely as described previously.17

Primary mixed lymphocyte reaction

Primary mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) cultures were performed by culturing 5 × 104 isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells or control CD4+CD25- T cells with 0.5 × 105 fully HLA-mismatched γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs in 200 μL culture medium (RPMI-1640 with glutamax supplemented with 0.02 mM pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin [all from Gibco, Paisley, United Kingdom], and 10% human pooled serum [HPS]) at 37°C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2 in 96-well round-bottom plates (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany). Recombinant human IL-2 (12.5 U/mL; Proleukine; Chiron, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and IL-15 (10 ng/mL; BioSource, Nivelles, Belgium) were added to the medium at the start of culture. Proliferation was analyzed by 3H-thymidine incorporation using a Gas Scintillation Counter (Matrix 96 Beta-counter; Canberra Packard, Meriden, CT). To this end 0.037 MBq (1 μCi) 3H-thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Irvine, CA) was added to each well, cells were harvested after 8 hours of culture, and 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured. The 3H-incorporation is expressed as mean plus or minus SD counts per 5 minutes of at least triplicate measurements.

CFSE labeling

T cells (0.5-2 × 106) were labeled with 0.2 to 1 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) just before stimulation. Intracellular esterases cleave the acetate groups leading to the fluorescent carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE). Cell division accompanied by CFSE dilution was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Sandimmune cyclosporine A (CsA) was obtained from Novartis Pharma B.V. (Arnhem, The Netherlands). Rapamycin was kindly provided for research purposes (Dr S. N. Sehgal, Wyeth-Ayerst, NJ).

MLR coculture assay to study T-cell suppressor function

The suppressor capacity of T cells was studied in a MLR coculture assay. CD4+CD25+ or CD4+CD25- T cells were primed with (target) alloantigen in the presence of recombinant human IL-2 and IL-15. Following expansion, the cells were harvested, washed, and allowed to rest for 3 days in medium containing 2% to 5% HPS and 5 ng/mL IL-15. The cells of interest were added to a newly set-up primary MLR, consisting of freshly thawed original responder PBMCs and γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs.

Flow cytometry

Cells were phenotypically analyzed by 4- or 5-color flow cytometry as described previously.17 The following conjugated mAbs were used: CD3 (UCHT1) PE, CD4 (MT310) PE, CD8 (DK25) PE, CD27 (M-T271) PE, CD25 (M-A251) PE (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL), FoxP3 (PCH101) FITC (Ebioscience, San Diego, CA), CD4 (T4) ECD, CD4 (T4) PC5, CD25 (B1.49.9) PC5, and CD62L (DREG54) ECD (Beckman Coulter). Isotype-matched antibodies were used to define marker settings. Intracellular analysis of CTLA4 and FOXP3 was performed after fixation and permeabilization, using Fix and Perm reagent (Ebioscience).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA), Microsoft Excel 2000 (Microsoft, Redman, WA), and Statistical Product and Services Solutions (SPSS) package version 12.0 (SPSS Science Chicago, IL). For comparisons between groups, we used, when appropriate, the Wilcoxon signed rank test or Student t test, assuming unequal variances because of small sample size. To determine the pooled standard deviation (Figure 6) we used the following formula: SDP = (((n1 - 1)(SD1)2) + ((n2 - 1)(SD2)2)/(n1+n2 - 2))1/2.

Results

CsA and rapamycin both permit the activation and suppressor function of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ TREGs

TREGs require activation to perform their immunoregulatory function. To asses whether CsA or rapamycin interfere in the allogeneic activation of suppressor function, we performed MLR coculture assays in the presence or absence of these drugs. Previous dose-response experiments indicated that CsA concentrations between 40 ng/mL and 400 ng/mL, and rapamycin concentrations between 10 nM and 1000 nM, are suboptimal for inhibition of the alloresponse of effector T cells.18 Repetition of these experiments yielded the same results (data not shown). Therefore, the use of these concentrations of drugs would allow us to asses an additional inhibition of effector T cells by added TREGs. Using this setup, we observed that the addition of CD4+CD25+ TREGs to both CsA- and rapamycin-treated cultures led to an enhanced inhibition of CD4+CD25- effector T-cell proliferation (Figure 1). Neither drug abrogated the suppressive effect of the added CD4+CD25+ TREGs. It can thus be concluded that biologically active concentrations of both CsA and rapamycin allow the activation and subsequent suppressor function of CD4+CD25+ TREGs.

CsA and rapamycin inhibit the alloantigen-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs

It can be envisaged that on activation of naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ TREGs, the induction of tolerance in vivo is further promoted by subsequent antigen-specific expansion of cells with regulatory capacity. Indeed, experimental transplantation models have demonstrated that alloantigen-specific CD4+CD25+ TREGs contribute significantly to transplantation tolerance.19,20 Therefore, we analyzed the effects of CsA and rapamycin on allogeneic expansion of freshly isolated, naturally occurring human CD4+CD25+ TREGs. To this end, freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with alloantigen and additional IL-2 and IL-15. These cytokines are known to drive cell division in activated CD4+CD25+ TREGs.13 At day 6 of culture in the absence or presence of various doses of CsA or rapamycin, we analyzed the level of cell division by calculating the percentage of nondividing T cells (Figure 2). As anticipated, in the drug-free condition, CD4+CD25+ TREGs proliferated strongly on fully allogeneic stimulation in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15, and only 36% of CD4+CD25+ TREGs were left in the nondividing population. In contrast, both CsA and rapamycin induced a pronounced inhibition of cell division. In the case of the highest concentrations of the drugs tested, we observed a nondividing cell population of 62% for CsA and 64% for rapamycin. Taken together, both CsA and rapamycin are able to inhibit the expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs on allogeneic activation in the presence of the T-cell growth factors IL-2 and IL-15.

CsA and rapamycin both allow the activation and regulatory action of CD4+CD25+ T cells. Primary MLR was set up with 1 × 105 responder CD4+CD25- T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) fully HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs. In coculture assays (right), CD4+CD25+ T cells were added in a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:4. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations (x axis). Proliferation at day 5 of culture as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment is shown (n = 5). *P < .05 for difference between groups.

CsA and rapamycin both allow the activation and regulatory action of CD4+CD25+ T cells. Primary MLR was set up with 1 × 105 responder CD4+CD25- T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) fully HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs. In coculture assays (right), CD4+CD25+ T cells were added in a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:4. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations (x axis). Proliferation at day 5 of culture as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment is shown (n = 5). *P < .05 for difference between groups.

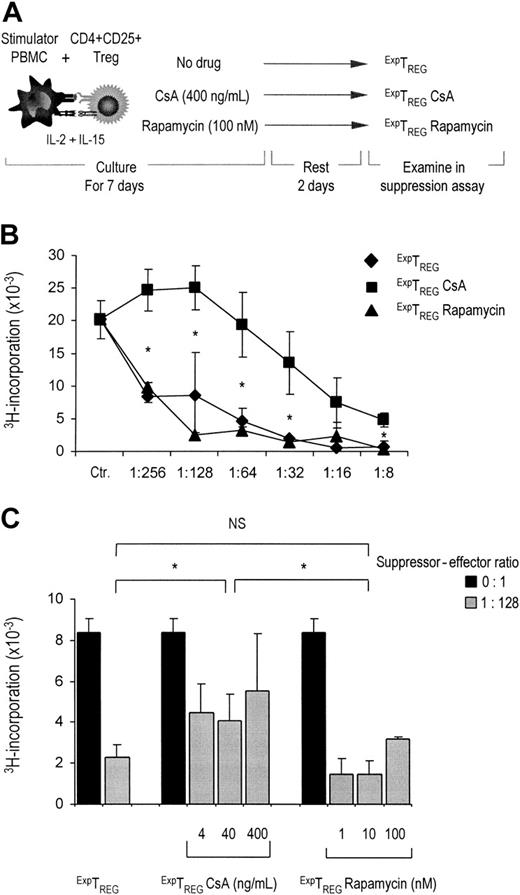

In contrast to CsA, rapamycin fully preserves the regulatory capacity of expanded CD4+CD25+ TREGs

Because antigen-driven expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs has been demonstrated to increase the suppressive capacity of the resultant population,13,21 a compromising effect of CsA or rapamycin on proliferation may weaken the regulatory function of the expanded population. To examine this, CD4+CD25+ TREGs were stimulated with alloantigen and additional IL-2 and IL-15 in the absence or presence of CsA (400 ng/mL) or rapamycin (100 nM). Subsequently, the cells were washed, rested for 2 days, and tested for suppressive capacity in coculture MLR (as depicted in Figure 3A). Strikingly, CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin displayed potent dose-dependent suppressive capacity similar to control cells, whereas suppression by CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of CsA was markedly reduced (Figure 3B). A 50% inhibition by TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin was reached already at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:256, whereas TREGs cultured in the presence of CsA reached a 50% inhibition at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:16. In other words, CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin were 16-fold more potent in suppressor capacity as compared with TREG cultured in the presence of CsA. This difference was observed irrespective of the concentrations that were used, as shown in Figure 3C for a single TREG/TEFFECTOR cell ratio. Thus, in contrast to CsA, rapamycin preserves suppressive capacity of TREGs over a broad range of concentrations.

CsA and rapamycin inhibit the allogeneic expansion of CD4+CD25+ T cells. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs (1 × 105) in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of the cultures at indicated concentrations. Cell division represented by the dilution of CFSE was analyzed by flow cytometry at day 6 of culture. Histograms show CFSE intensity (x axis) and the number of events (y axis). One representative experiment is shown (n = 4).

CsA and rapamycin inhibit the allogeneic expansion of CD4+CD25+ T cells. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were labeled with CFSE and stimulated with γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs (1 × 105) in the presence of IL-2 and IL-15. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of the cultures at indicated concentrations. Cell division represented by the dilution of CFSE was analyzed by flow cytometry at day 6 of culture. Histograms show CFSE intensity (x axis) and the number of events (y axis). One representative experiment is shown (n = 4).

Rapamycin fosters regulatory function of expanded CD4+CD25+ T cells. (A) Schematic representation of CD4+CD25+ T-cell expansion culture. (B) Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15, in the absence or presence of CsA and rapamycin. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of the cultures at indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested at day 7, washed 3 times, and rested. At day 10, the cells were examined for suppressor function in coculture assays. ExpTREGs derived from control (untreated), CsA-treated, and rapamycin-treated cultures were cocultured at the indicated suppressor-to-effector ratios (x axis) using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment is shown (n = 6). *P < .05 for difference between groups. (C) CD4+CD25+ T cells were cultured as described for panel B. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations (x axis). Cells were harvested at day 7, washed, rested, and cocultured at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:128 with 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs ( ). Control cultures were performed without the addition of suppressor cells (▪). Proliferation at day 5 of culture, as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation, is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. Because of small sample sizes, the conditions in which treated cells were used were grouped together, resulting in 3 groups: untreated cells, CsA-treated cells, and rapamycin-treated cells. *P < .01 for difference between groups. NS indicates not significant.

). Control cultures were performed without the addition of suppressor cells (▪). Proliferation at day 5 of culture, as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation, is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. Because of small sample sizes, the conditions in which treated cells were used were grouped together, resulting in 3 groups: untreated cells, CsA-treated cells, and rapamycin-treated cells. *P < .01 for difference between groups. NS indicates not significant.

Rapamycin fosters regulatory function of expanded CD4+CD25+ T cells. (A) Schematic representation of CD4+CD25+ T-cell expansion culture. (B) Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15, in the absence or presence of CsA and rapamycin. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of the cultures at indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested at day 7, washed 3 times, and rested. At day 10, the cells were examined for suppressor function in coculture assays. ExpTREGs derived from control (untreated), CsA-treated, and rapamycin-treated cultures were cocultured at the indicated suppressor-to-effector ratios (x axis) using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment is shown (n = 6). *P < .05 for difference between groups. (C) CD4+CD25+ T cells were cultured as described for panel B. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations (x axis). Cells were harvested at day 7, washed, rested, and cocultured at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:128 with 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs ( ). Control cultures were performed without the addition of suppressor cells (▪). Proliferation at day 5 of culture, as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation, is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. Because of small sample sizes, the conditions in which treated cells were used were grouped together, resulting in 3 groups: untreated cells, CsA-treated cells, and rapamycin-treated cells. *P < .01 for difference between groups. NS indicates not significant.

). Control cultures were performed without the addition of suppressor cells (▪). Proliferation at day 5 of culture, as measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation, is shown on the y axis. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. Because of small sample sizes, the conditions in which treated cells were used were grouped together, resulting in 3 groups: untreated cells, CsA-treated cells, and rapamycin-treated cells. *P < .01 for difference between groups. NS indicates not significant.

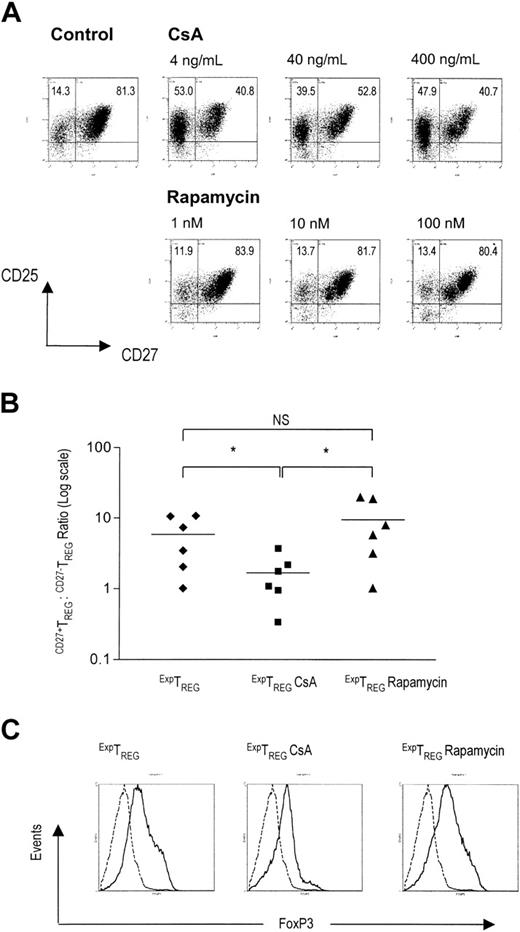

In contrast to CsA, rapamycin favors potent suppression by allowing a beneficial CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio

Previously, we demonstrated that after allogeneic expansion the CD4+CD25+ TREG pool is composed of subsets of CD27-TREGs and extremely potent CD27+TREGs. On the basis of this observation and literature data14-16 it is conceivable that the proportion of the highly potent CD27+TREG subset relative to the CD27-TREG subset will determine the overall suppressive capacity of the expanded TREG pool. Therefore, we analyzed the proportions of CD27+TREGs and CD27-TREGs present in CD4+CD25+ TREGs after allogeneic expansion in the presence of CsA or rapamycin. CD4+CD25+ TREGs were cultured for 7 days in the presence of various concentrations of CsA or rapamycin. After 2 days of rest (ie, prior to putative addition to coculture MLR), cells were analyzed for the expression of CD25 and CD27. Interestingly, the TREG pool cultured in the presence of rapamycin was, similar to control cells, dominated by the CD27+TREG subset, whereas the TREG pool cultured in the presence of CsA contained a relatively large proportion of CD27-TREGs (Figure 4A).

In six independent experiments, the CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratios within the CD25+ pool were determined after TREG expansion in the absence or presence of immunosuppressive agents. It was found that TREG expansion in the presence of CsA consistently resulted in a significant decrease of the CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio relative to TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin or in the absence of either drug (Figure 4B, P < .05). Thus, expansion in the presence of rapamycin, and not CsA, preserves the highly potent CD27+TREG subset.

Previously, CD4+CD25+CD27+ TREGs were characterized by a high FOXP3 expression level.16 Corresponding to the higher content of CD27+TREGs, CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin or in the absence of drugs displayed higher FOXP3 expression than cells cultured in the presence of CsA (Figure 4C).

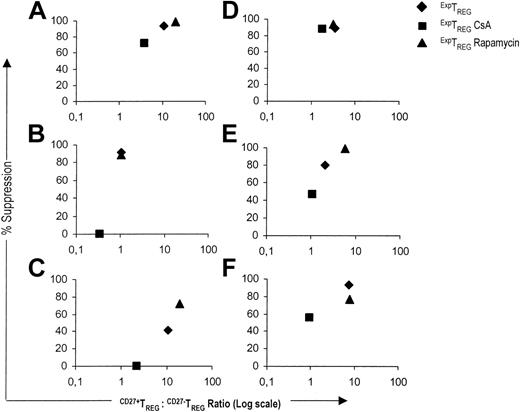

Subsequently, we analyzed the relationship between the CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio and the suppressive capacity for CD4+CD25+ TREG populations cultured in the presence of CsA or rapamycin. In five of six experiments, the low CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio of TREGs cultured in the presence of CsA corresponded to reduced suppressor potency. Conversely, when TREGs were cultured in the presence of rapamycin or in the absence of drugs, a high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio was related to a stronger suppressive activity (Figure 5).

In summary, the CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio crucially determines the suppressive capacity of the expanded TREG pool as a whole. In contrast to CsA, rapamycin favors potent suppression by allowing a beneficial CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio.

Rapamycin preserves a high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG ratio. (A) The expression of CD25 and CD27 on CD4+CD25+ TREG expanded in the absence or presence of CsA or rapamycin was measured by flow cytometry. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) allogeneic PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested at day 7, washed, rested, and analyzed for CD25 and CD27 expression at day 10 of culture. Dot plots show CD25 and CD27 expression of live-gated cells. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratios (y axis) within the CD25+ fraction were calculated for the ExpTREG pool, the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin). The results of 6 independent experiments are shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups. (C) The intracellular expression profile of FOXP3 in the ExpTREG pool, the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin) was determined by flow cytometry. Histograms show intracellular FOXP3 expression of live-gated cells. Dotted line indicates CD4+CD25- cells; solid line, CD4+CD25+ cells.

Rapamycin preserves a high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG ratio. (A) The expression of CD25 and CD27 on CD4+CD25+ TREG expanded in the absence or presence of CsA or rapamycin was measured by flow cytometry. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) allogeneic PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15. CsA and rapamycin were added at the start of primary MLR at indicated concentrations. Cells were harvested at day 7, washed, rested, and analyzed for CD25 and CD27 expression at day 10 of culture. Dot plots show CD25 and CD27 expression of live-gated cells. One representative experiment of 3 independent experiments is shown. (B) CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratios (y axis) within the CD25+ fraction were calculated for the ExpTREG pool, the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin). The results of 6 independent experiments are shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups. (C) The intracellular expression profile of FOXP3 in the ExpTREG pool, the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin) was determined by flow cytometry. Histograms show intracellular FOXP3 expression of live-gated cells. Dotted line indicates CD4+CD25- cells; solid line, CD4+CD25+ cells.

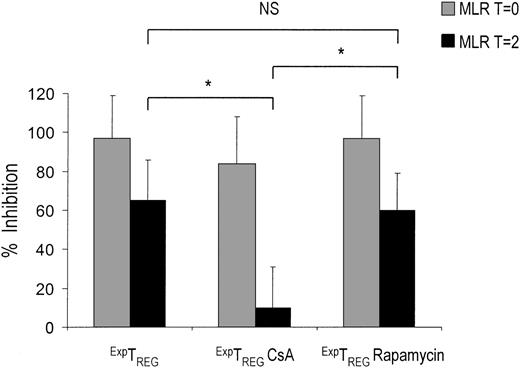

Only CD4+CD25+ TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin inhibit ongoing T-cell responses

In patients who receive a transplant and who have been primed with alloantigens, or in patients presenting with T-cell–mediated autoimmune diseases, it is crucial to restrain T-cell responses that are already in progress. As described previously, a crucial difference between CD27+TREGs and CD27-TREGs is the ability of CD27+TREGs to inhibit ongoing T-cell responses. Because rapamycin, but not CsA, preserves the CD27+TREG pool, it can be hypothesized that TREGs cultured in the presence of either drug differ with respect to their ability to inhibit ongoing T-cell responses. Therefore, we analyzed the potential of TREGs cultured in the presence of immunosuppressive drugs to inhibit effector T-cell proliferation at an advanced state of a MLR. Notably, TREGs cultured in the presence of CsA lost the ability to prevent ongoing T-cell responses of 2 days after the start of MLR, whereas TREGs cultured in the presence of rapamycin were still able to suppress this response (Figure 6).

A high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG ratio corresponds to potent suppression. The relative suppression (y axis) at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:128 was plotted against the corresponding CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio (x axis) for the ExpTREG pool (♦), the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA) (▪), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin) (▴). The results of 6 independent experiments are shown.

A high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG ratio corresponds to potent suppression. The relative suppression (y axis) at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:128 was plotted against the corresponding CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio (x axis) for the ExpTREG pool (♦), the ExpTREG CsA pool (cultured with 400 ng/mL CsA) (▪), and the ExpTREG rapamycin pool (cultured with 100 nM rapamycin) (▴). The results of 6 independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

In several experimental transplantation models, it has been observed that CsA can antagonize the induction of tolerance, whereas rapamycin does not.22-25 One mechanism that may account for these observations is that in contrast to CsA, rapamycin easily permits apoptosis of alloreactive T cells.8 Another possibility is that both drugs have different effects on TREGs because these cells have been demonstrated to play an important role in many models of tolerance induction.9 Indeed, it was reported that CsA, and not rapamycin, blocks the generation of TREGs after pretransplantation donor-specific blood transfusion in rats.12 Furthermore, a relative increase of CD4+CD25+ T cells in peripheral lymphoid organs was observed in rats treated with rapamycin. Recently, Battaglia et al11 described that exposure to rapamycin results in a selective expansion of murine CD4+CD25+ TREGs in vitro.

We here present a novel explanation for the favorable immunomodulatory effects of rapamycin. First of all, we confirm that both rapamycin and CsA allow the activation and suppressor function of human TREGs. As a new finding, we demonstrate that after allogeneic stimulation of human naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ TREGs, rapamycin treatment fosters a high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG subset ratio. Recently, we described the characteristics of these 2 TREG subsets induced on allogeneic expansion of human CD4+CD25+ TREGs.13 A major difference between these subsets is their suppressive capacity, the CD27+TREG subset being highly suppressive, whereas the CD27-TREG subset has modest suppressive potency.13 The strong regulatory capacity of the CD27+TREG subset has also been shown in other studies.14-16 After expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs, we typically find that the majority of cells are CD27+. In this study we show that rapamycin and CsA act differently with regard to the preservation of the high CD27+TREG/CD27-TREG ratio. In contrast to CsA, rapamycin preserved the dominance of CD27+TREGs over CD27-TREGs on allogeneic stimulation, resulting in strong suppressive capacity of the expanded CD4+CD25+ TREG pool as a whole. It can thus be envisaged that a predominance of CD27+TREGs, which is supported by treatment with rapamycin, can add to the development of stable tolerance and prevention of rejection in solid-organ transplantation. Also in stem cell transplantation, patients may benefit from the use of rapamycin as immunosuppressant, for it becomes increasingly clear that the presence of potent CD4+CD25+ TREGs favors immune reconstitution and may control graft-versus-host disease while allowing graft-versus-tumor activity.26,27

Next to the beneficial effect of CD27+TREGs, the relevance of the CD27-TREGs as such should not be discarded. It can be expected that after transplantation CD4+CD25+ TREGs will expand in an antigen-specific manner in the draining lymph nodes or in the graft.28,29 Of note, CD27+TREGs and CD27-TREGs differ with respect to the pattern of migratory receptors and adhesion molecules. CD27+TREGs were found to express CD62L, whereas CD27-TREGs were devoid of CD62L.13 It can thus be argued that CD27+TREGs are committed to local suppressor function in the draining lymph node, whereas CD27-TREGs are destined to enter the periphery. Moreover, CD27-TREGs are characterized by rapid expansion, which may be of importance in outnumbering aggressive T cells in the periphery.13 So, CD27-TREGs may have a specific role, and in vivo it may well be that the induction of transplantation tolerance benefits from the use of CsA in specific cases. In fact, CsA has been implicated in the induction of transplantation tolerance by sparing of CD4+ suppressor cells and when used in combination with costimulation blocking agents.12,30-34 Further research on the in vivo role of CD27+TREGs and CD27-TREGs may elucidate how the effect of rapamycin and CsA on the skewing of TREG subsets may differentially affect the induction of allograft tolerance.

The frequency of CD27+TREGs is clearly affected by CsA. Crosslinking of CD27 has been shown to induce proliferation following the mobilization of intracellular free Ca2+.35,36 Because CsA specifically targets Ca2+-dependent activation pathways, CsA may thus selectively inhibit CD27+TREG proliferation. However, we have preliminary data that do not support an inhibition of proliferation (data not shown), rather it appears that CD27 expression levels are affected on stimulation in the presence of CsA. This is in agreement with the previous finding that elevation of intracellular Ca2+ levels is important in the up-regulation of CD27 expression.36

CD4+CD25+ T cells cultured in the presence of rapamycin, but not CsA, are able to inhibit ongoing T-cell responses. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15 in the absence or presence of CsA (400 ng/mL) and rapamycin (100 nM). Cells were harvested at day 7, washed 3 times, and rested. At day 10, the cells were examined for suppressor function in suppression coculture assays. ExpTREGs derived from control (untreated), CsA-treated, and rapamycin-treated cultures (x axis) were cocultured from day 0 (T = 0) ( ) or day 2 (T = 2) (▪) of MLR at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:16 using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and is depicted as a percentage of inhibition on the y axis. A representative experiment is shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups.

) or day 2 (T = 2) (▪) of MLR at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:16 using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and is depicted as a percentage of inhibition on the y axis. A representative experiment is shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups.

CD4+CD25+ T cells cultured in the presence of rapamycin, but not CsA, are able to inhibit ongoing T-cell responses. Freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ T cells (2.5 × 104) were stimulated with 1 × 105 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) HLA-mismatched stimulator PBMCs and additional IL-2 and IL-15 in the absence or presence of CsA (400 ng/mL) and rapamycin (100 nM). Cells were harvested at day 7, washed 3 times, and rested. At day 10, the cells were examined for suppressor function in suppression coculture assays. ExpTREGs derived from control (untreated), CsA-treated, and rapamycin-treated cultures (x axis) were cocultured from day 0 (T = 0) ( ) or day 2 (T = 2) (▪) of MLR at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:16 using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and is depicted as a percentage of inhibition on the y axis. A representative experiment is shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups.

) or day 2 (T = 2) (▪) of MLR at a suppressor-to-effector ratio of 1:16 using 5 × 104 responder CD4+CD25- effector T cells and 5 × 104 γ-irradiated (30 Gy) stimulator PBMCs. Proliferation at day 5 of culture was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation and is depicted as a percentage of inhibition on the y axis. A representative experiment is shown. *P < .05 for difference between groups.

It has been proposed that signaling by the growth factor IL-2 is crucial for the functional activity of TREGs.4,5 CsA inhibits TCR-induced activation and IL-2 production, whereas rapamycin blocks signaling in response to T-cell growth factors.6,7 In theory, both drugs could therefore interfere with the function of TREG function. Interestingly, we observed that in the presence of CsA or rapamycin freshly isolated CD4+CD25+ TREGs were able to suppress CD4+CD25- T cells, indicating that CsA and rapamycin did not significantly interfere in the activation or suppressor function of these cells. In line with these findings, basiliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody directed against the IL-2 receptor, also did not interfere in the suppressive capacity of human CD4+CD25+ T cells.37 This may indicate that inhibition of the IL-2 pathways is not as detrimental to the function of human CD4+CD25+ TREGs as could be expected from in vivo findings on CD4+CD25+ TREGsina mouse model.38

In summary, our data show that CsA and rapamycin do not interfere with the activation or suppressor function of freshly isolated human CD4+CD25+ TREGs. However, CsA and rapamycin differentially affect TREG-subset heterogeneity on expansion after allogeneic activation. Expansion of CD4+CD25+ TREGs in the presence of rapamycin favors CD27+TREG-subset dominance, which is beneficial for the suppressive capacity of the CD4+CD25+ T-cell pool as a whole and allows the suppression of ongoing T-cell responses. During expansion of TREGs in the presence of CsA, the dominance of the CD27+TREG subset is lost, and this is accompanied by a decrease of suppressive activity of the resulting population. These findings provide a novel contribution to explain the favorable effects of rapamycin in strategies of tolerance induction.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, October 6, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3032.

Supported by a grant from the Dutch Kidney Foundation.

J.J.A.C. and H.J.P.M.K. contributed equally to this study.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal