Comment on Zhou et al, page 3251

In this issue of Blood, Zhou and colleagues demonstrate that the coordinate activation of both innate and adaptive immunity and the limitation of regulatory T cells in mice immunized with a DNA vaccine enhance the ability of the host immune system to control colon carcinoma.

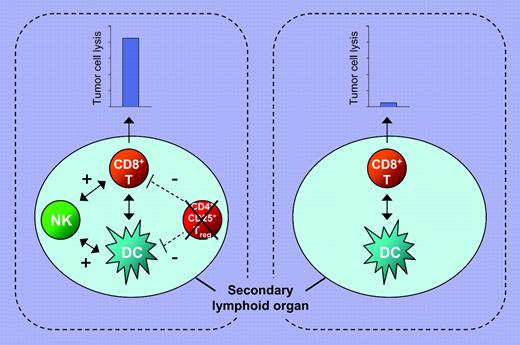

Using a pH60/Survivin DNA vaccine, which simultaneously engages the NKG2D receptor with the ligand H60 and targets survivin as a tumor antigen,1 Zhou and colleagues show that cross talk between dendritic cells (DCs), natural killer (NK) cells, and T cells is essential to the generation of enhanced immunity against tumor cells (see figure). The authors' results provide further evidence that optimal priming of CD8+ T cells, which requires their interaction with activated and mature DC populations, is influenced by NK cells.2 An additional intriguing and novel observation of Zhou and colleagues is the reduction in the regulatory T-cell number at the vaccine priming site in mice immunized with this DNA vaccine, thus limiting the negative role of regulatory T cells in the induction of a tumor antigen–specific immune response.3 These findings, in conjunction with the recently described requirement for the cooperation of the cellular and humoral arms of the immune system for effective eradication of HER2-positive tumors in a mouse model system,4 emphasize the need to change our approach in the clinical application of immunotherapy of malignant diseases. Thus far, the emphasis has been on the activation of one arm of the immune system, in the majority of cases T-cell immunity, since T cells are believed to be the major players in tumor control. The available experimental evidence argues that activation of multiple arms of the immune system is a must to enhance the ability of immunotherapy to control tumor growth.FIG1

Enhanced tumor antigen–specific CTL response is generated by cross talk between NK cells, DCs, and CD8+ T cells and reduction in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cell numbers at the priming site. Immunization strategies that trigger the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system and reduce the number of Treg cells generate a more effective tumor antigen–specific CTL response (left panel) than those that trigger only the adaptive arm of the immune system (right panel).

Enhanced tumor antigen–specific CTL response is generated by cross talk between NK cells, DCs, and CD8+ T cells and reduction in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cell numbers at the priming site. Immunization strategies that trigger the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system and reduce the number of Treg cells generate a more effective tumor antigen–specific CTL response (left panel) than those that trigger only the adaptive arm of the immune system (right panel).

As any good study does, the present work raises several questions. Is the described DNA vaccine active against any type of tumor? Do defects in survivin presentation by tumor cells to cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), because of abnormalities in the encoding gene or in MHC class I antigens,5 provide an escape mechanism to tumor cells? Or can other effector cells counteract it? What is the frequency of survivin loss or down-regulation, especially in tumor cells subjected to selective pressure? Would the described strategy benefit from the cooperation of the humoral arm of the immune system? Would its anti-tumor efficacy be enhanced by the addition of antibodies that selectively deplete the host of regulatory T cells?6 Given the genomic instability of tumor cells, should one also target surrounding normal cells, which are crucial contributors to tumor cell survival and growth?

An even more fundamental question is the following: What is the clinical relevance of the described studies? More specifically, will the described vaccine be as effective in patients with malignant disease as in the animal model system? Can enhancing the immune response by the cross talk between adaptive and innate immune system cells increase the chances of overcoming some of the limitations currently being encountered in the translation of active specific immunotherapeutic strategies to theclinical setting? The present study has set the stage for addressing these questions. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal