Abstract

In Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), the malignant Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells constitute only 0.5% of 10% of the diseased tissue. The surrounding cellular infiltrate is enriched with T cells that are hypothesized to modulate antitumor immunity. We show that a marker of regulatory T cells, LAG-3, is strongly expressed on infiltrating lymphocytes present in proximity to HRS cells. Circulating regulatory T cells (CD4+ CD25hi CD45 ROhi, CD4+ CTLA4hi, and CD4+ LAG-3hi) were elevated in HL patients with active disease when compared with remission. Longitudinal profiling of EBV-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in 94 HL patients revealed a selective loss of interferon-γ expression by CD8+ T cells specific for latent membrane proteins 1 and 2 (LMP1/2), irrespective of EBV tissue status. Intratumoral LAG-3 expression was associated with EBV tissue positivity, whereas FOXP3 was linked with neither LAG-3 nor EBV tissue status. The level of LAG-3 and FOXP3 expression on the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was coincident with impairment of LMP1/2-specific T-cell function. In vitro pre-exposure of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to HRS cell line supernatant significantly increased the expansion of regulatory T cells and suppressed LMP-specific T-cell responses. Deletion of CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells enhanced LMP-specific reactivity. These findings indicate a pivotal role for regulatory T cells and LAG-3 in the suppression of EBV-specific cell-mediated immunity in HL.

Introduction

There is now compelling evidence that latent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection is controlled by a population of virus-specific (largely CD8+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). These CTLs recognize epitopes frequently derived from EBV nuclear antigens (EBNA) 2, 3, 4, and 6.1,2 Although the mechanisms involved in controlling intermittent virus reactivation from latency have not yet been completely defined, it is clear that the interaction between specific CTLs and their targets form a key element in preventing unchecked viral proliferation.

EBV-associated malignancies can arise in both immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. These malignancies are of variable cellular origin and, while some involve specific genetic lesions, all involve the expression of either some or all of the EBV latent proteins (reviewed by Khanna et al1 ). In developed countries EBV may be implicated in the pathogenesis of 30% to 50% of cases of Hodgkin lymphoma (HL),1,3-5 and cell-free EBV DNA can be used as a biomarker for EBV-positive HL such that serial monitoring can predict response to therapy.6 In EBV-positive HL, most viral genome-positive cells are monoclonal, indicating that infection of the malignant B cells occurred before clonal expansion.7 Serologically confirmed infectious mononucleosis–related EBV infection is associated with an increased risk of EBV-positive HL in young adults.8 Like many other EBV-associated malignancies, the malignant B cells (referred to as Hodgkin Reed-Sternberg [HRS] cells) in HL are characterized by their unique viral and cellular phenotype. HRS cells display a type II form of latency with viral antigen expression limited to EBNA1, latent membrane proteins 1 and 2 (LMP1/2), as well as the EBER1, EBER2, and BamHIA transcripts.9 Recent data describe a specific HLA class I association with EBV-positive HL, suggesting that deficient antigenic presentation of LMP1/2 peptides may be involved in the pathogenesis of EBV-positive HL.10 Furthermore, HRS cells have evolved multiple strategies to evade the potent EBV-specific CTL response, and these have been proposed to be linked to the cell-mediated immune deficiency that is present in the early phase of the disease.

Although most patients with HL can be cured with currently available therapies, up to 30% of patients with advanced HL will progress or relapse.11 New, more intensive chemotherapy regimens have significantly improved outcome12 ; however, less than half of relapsed and refractory patients will respond to conventional salvage strategies. These data have raised the possibility of combining immunotherapy with chemotherapy/radiotherapy, particularly in patients with relapsed/refractory EBV-positive HL. Indeed, a number of attempts have been made to expand EBV-specific T-cell immunity in vitro in the absence of an immunosuppressive environment and to transfer the resulting expanded T cells to treat patients with HL.13,14 However, an objective analysis of disease outcome highlights the need to explore alternate strategies to break tumor evasion mechanisms that preclude the development of a robust antitumor response. To enable further development of these strategies, it is important to understand the mechanism(s) by which the existing immune response to EBV-encoded antigens fails to block the outgrowth of malignant cells. Previous studies on HL patients have indicated that EBV-specific T cells can be detected in the peripheral circulation that recognize EBV-specific antigens that are expressed in HRS cells, yet this rarely corresponds with effective tumor eradication.15,16 Recent studies on human malignancies have suggested that the lack of an effective antitumor response may be due to activation of unique subsets of CD4+ Treg cells that specifically inhibit antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.17 HL is a unique clinicopathologic entity in which the malignant HRS cells typically constitute only 0.1% to 10% of the diseased tissue.18 Immunohistochemical and flow cytometric analysis of the surrounding cellular infiltrate from HL lymph nodes shows enrichment with cells that express the typical phenotypic markers of Treg cells, including FOXP3, TGF-β, and CTLA-4.19-21 Functional assays confirm that these infiltrating cells are capable of suppressing interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production and proliferation of autologous peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) to mitogens and recall antigens.19 However, a role for Treg cells in modulating EBV-specific T-cell immunity against the EBV latent antigens expressed in HL has not previously been explored.

Here, in a collaborative study conducted under the auspices of the Australasian Leukaemia & Lymphoma Group (ALLG), we have prospectively profiled intratumoral lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3) expression, which has recently been shown to be selectively up-regulated on Treg cells.22 Our aim was to investigate an association between Treg cells, the LAG-3 protein, and the EBV peptide–specific T-cell responses in HL patients. Having demonstrated that the level of LAG-3 expression on the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was coincident with the loss of LMP1/2-specific T-cell function, we then went on to establish that CD4+ LAG-3 T cells had regulatory properties. The data presented here firmly establish the importance of CD8+ T-cell responses to LMP1/2 antigens and have important implications for understanding the pathogenesis of HL.

Patients, materials, and methods

Study participants

A total of 94 newly diagnosed (ND), relapsed (RL), and remission (2 years from diagnosis) patients with histologically confirmed HL were included in this study. Table 1 provides details of the patient characteristics. One patient withdrew prior to providing samples. Data regarding age, sex, date of diagnosis, and histology were collected in all patients. Mean age of the total group was 32 years (range, 5 to 76 years), and 38% were female. In newly diagnosed and relapsed patients, additional prognostic information was obtained to enable the prognostic score to be calculated.23 To serve as controls, enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) analysis was performed on blood from 29 healthy subjects (12 female, 17 male; mean age, 43 years; range, 23 to 63 years). There was no significant difference in sex mix between the 4 groups; however, both RL patients and healthy subjects were significantly older than ND patients (P = .05 and P < .001, respectively) and remission patients (P = .011 and P < .001, respectively). This study conformed to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was provided as per each participating site's research ethics process. This study was formally approved by the Human Ethics committees of Queensland Institute of Medical Research, Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, and Princess Alexandra Hospital.

Patient characteristics

Characteristic . | Newly diagnosed . | Relapsed . | Long-term remission . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 41 | 9 | 43 |

| Sex, F/M | 14/27 | 5/4 | 17/26 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y | 31 | 41 | 30 |

| Clinical stage IIB/III/IV, no. (%) | 20 (49) | 5 (66) | Not applicable |

| Prognostic score 3 or more*, no. (%) | 12 (29) | 4 (44) | Not applicable |

| Timing of blood sample(s) | Prior to therapy, 6 mo, 12 mo | Prior to therapy, 6 mo, 12 mo | Mean, 5 y; range, 2-33 y after diagnosis |

| Histology†, no. of total (%) | |||

| Nodular sclerosing | 27/41 (66) | 7/9 (78) | 18/36 (50) |

| Mixed cellularity | 7/41 (17) | 1/9 (11) | 6/36 (17) |

| Lymphocyte rich | 4/41 (10) | 0/9 (0) | 4/36 (11) |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 1/41 (2) | 0/9 (0) | 1/36 (3) |

| Nodular lymphocyte predominant | 2/41 (5) | 1/9 (11) | 3/36 (8) |

| Unclassified Hodgkin | 0/41 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 4/36 (11) |

| Positive EBV serology‡, no. of total (%) | 39/40 (98) | 8/9 (89) | 40/43 (93) |

| Positive EBV tissue status§, no. of total (%) | 15/41 (36) | 1/9 (11) | 9/27 (33) |

Characteristic . | Newly diagnosed . | Relapsed . | Long-term remission . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of patients | 41 | 9 | 43 |

| Sex, F/M | 14/27 | 5/4 | 17/26 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, y | 31 | 41 | 30 |

| Clinical stage IIB/III/IV, no. (%) | 20 (49) | 5 (66) | Not applicable |

| Prognostic score 3 or more*, no. (%) | 12 (29) | 4 (44) | Not applicable |

| Timing of blood sample(s) | Prior to therapy, 6 mo, 12 mo | Prior to therapy, 6 mo, 12 mo | Mean, 5 y; range, 2-33 y after diagnosis |

| Histology†, no. of total (%) | |||

| Nodular sclerosing | 27/41 (66) | 7/9 (78) | 18/36 (50) |

| Mixed cellularity | 7/41 (17) | 1/9 (11) | 6/36 (17) |

| Lymphocyte rich | 4/41 (10) | 0/9 (0) | 4/36 (11) |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 1/41 (2) | 0/9 (0) | 1/36 (3) |

| Nodular lymphocyte predominant | 2/41 (5) | 1/9 (11) | 3/36 (8) |

| Unclassified Hodgkin | 0/41 (0) | 0/9 (0) | 4/36 (11) |

| Positive EBV serology‡, no. of total (%) | 39/40 (98) | 8/9 (89) | 40/43 (93) |

| Positive EBV tissue status§, no. of total (%) | 15/41 (36) | 1/9 (11) | 9/27 (33) |

Hasenclever/Diehl International Prognostic Score.

Histology available in all newly diagnosed and relapsed cases and 36 of 43 (84%) remission cases.

Serology undetermined in 1 newly diagnosed case.

Biopsy available for EBV testing in all newly diagnosed and relapsed cases and 27 of 43 (63%) remission cases. EBV tissue status correlated with histology, with 55% of mixed cellularity or lymphocyte-rich cases positive for EBV, against 27% of nodular sclerosing cases (r = 0.38, P = .013). In 2 of 67 cases the LMP1 and EBER stains were discordant (EBER positive/LMP1 negative). Both cases were classified as EBV tissue positive.

Tissue staining

All assays were carried out on sections of routinely fixed, paraffin-embedded material. LMP1 and EBER assays were performed as per published guidelines.7 The distribution of HRS cells was assessed by a morphologist on matching hematoxylin and eosin slides prior to interpreting the LMP1 and EBER staining. Following antigen retrieval with trypsin, the anti-LMP IgG1 or isotype control (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) was used to detect the presence of LMP1. Positive reactivity was detected as per manufacturer's instructions incorporating DAB as the chromogenic substrate (Envision kit; Dako). The EBER in situ hybridization assay used a commercially available hybridization kit (Dako) and custom-made probes derived from EBER1 and EBER2.24 A fluoresceinated poly-dT oligonucleotide probe was used to hybridize to polyA mRNA in the tissue sections to serve as a control for tissue and mRNA integrity. For all stains, a known case of EBV-positive posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (responsive to EBV-specific CTL therapy) was used as a positive control.

LAG-3 and FOXP3 immunohistochemistry were performed as per manufacturer's guidelines (Novacastra, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, United Kingdom, and Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom, respectively). For both proteins, tonsillar tissue was used as a positive control, and a characteristic interfollicular pattern was seen.

Blood samples

In ND and RL cases, 30 mL of EDTA blood was taken at diagnosis (prior to initiation of therapy) and then at 6-month intervals for 1 year. With healthy subjects and remission cases, one 30-mL blood sample was taken, and in the latter group the time interval from sample to diagnosis recorded. PBMCs were prepared by gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; Amersham Biosciences, Björkgatan, Sweden). PBMCs were stored by controlled rate freezing in liquid nitrogen, and plasma samples were stored at –70°C until further processing.

Synthetic peptides

Twenty-nine EBV-epitope synthetic peptides presented by a wide range of HLA class I alleles covering more than 90% of white subjects were used in this study (HLA restriction in parentheses): latent cycle protein LMP1 peptides YLLEMLWRL (A2), YLQQNWWTL (A2), ALLVYLSFA (A2), and IALYLQQNW (B57)25,26 ; latent cycle protein LMP2A peptides FLYALALLL (A2), CLGGLLTMV (A2), LTAGFIFL (A2), SSCSSCPLSKI (A11), PYLFWLAAI (A23/24), TYGPVFMCL (A24), VMSNTLLSAW (A25), FTASVSTVV (A28), and IEDPPFNSL (B60)16,27 ; latent cycle protein EBNA3 peptides RLRAEAQVK (A3), RYSIFFDY (A24), RPPIFRRL (B7), FLRGRAYGL (B8), QAKWRLQTL (B8), and YPLHEQHGM (B35)28-31 ; latent cycle protein EBNA4 peptides AVFDRKSKAK (A11), IVTDFSVIK (A11), AVLLHEESM (B35), and GQGGSPTAM (B62)32 ; latent cycle protein EBNA6 peptides LLDVRFMGV (B37), EENLLDFVRF (B44.02), and EGGVGWRHW (B44.03)31,33,34 ; and lytic cycle protein peptides GLCTLVAML (A2), RAKFKQLL (B8), and DYCNVLNKEF (A24),35-37 derived from BMLF1, BZLF1, and BRLF1 respectively. All epitope peptides will be subsequently abbreviated to the first 3 amino acids throughout this text. The peptides were purchased from Mimotopes Pty (Melbourne, Australia) and dissolved in 20% dimethyl sulfoxide at 2 mg/mL and diluted in RPMI 1640 to a final concentration of 10 μg/mL.

Peptide-specific T-cell cytokine secretion by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

The IFN-γ ELISPOT assay has been described in detail elsewhere.26 Spots were counted automatically using image analysis software (ImagePro, Silver Spring, MD) and were expressed as spot-forming cells (SFCs) per 106 PBMCs. The number of IFN-γ secreting T cells was calculated by subtracting the negative control value from the SFC count.

Flow cytometry

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), or TriColour (TC) were specific for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD28, CD25, CD45RO, and CTLA-4 (TCS Biologicals, Burlingdale, CA), GITR (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), LAG-3 (Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA), and relevant isotype controls. Intracellular expression of CTLA-4 and GITR was performed as per manufacturer's instructions (Cytofix/Cytoperm kit; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, and eBioscience, San Diego, CA, respectively). We used peptide–major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I pentamers (Proimmune, Oxford, United Kingdom) to visualize T cells recognizing the EBV peptides YLL, YLQ, FLY, IED, CLG, FLR, RPP, GLC, and RAK. Staining of lymphocytes was undertaken by incubating the cells with a pretitrated concentration of pentamer at room temperature for 20 minutes. The cells then were then washed in staining buffer and stained for surface markers by incubation at 4°C for 15 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed on a FACS Canto (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA) cytometer and results analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Stanford, CA) software.

In vitro exposure of PBMCs to cell-line supernatants

To determine the effect of exposure of PBMCs to HL cell line supernatants, 2 × 106 PBMCs were incubated in either serum-free culture media (SFCM) or supernatants from HRS cell lines (L1236, HDLM2, L428, L54038-40 ). These cell lines had been previously cultured in SFCM. In some experiments, CD4+ and LAG-3+ T cells were depleted from these PBMCs. This depletion was carried out using a MoFlo high-performance cell sorter (Dako). Prior to cell sorting, PBMCs were stained with PE-labeled anti-CD4 and FITC-labeled anti–LAG-3 antibodies. After incubation, these cells were analyzed for CTLA-4 expression and ELISPOT assays as described in the two preceding sections.

Statistics

Comparison of patient sex and age between groups was performed using the nonpaired t test. For ex vivo studies using IFN-γ ELISPOT, flow cytometry, and peptide–HLA class I pentamers, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test for unpaired groups was used to analyze samples from different time points. Associations between EBV tissue status, percent LAG-3, percent FOXP3, and histology were performed using the χ2 test. The Wilcoxon matched pairs test was used to compare paired T-cell subsets generated within PBMCs following exposure to HRS cell supernatants and for analysis of pretherapy and posttherapy ELISPOT data. All P values were 2 sided, with values less than .05 considered significant. All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA.

Results

Intratumoral and peripheral-blood lymphocytes from HL patients express high levels of LAG-3

Recent studies in a murine model have identified LAG-3 as a cell-surface molecule that is selectively up-regulated on Treg cells and may be directly involved in mediating Treg function.22 To explore the potential role of LAG-3 in HL, we investigated the expression of this marker on both tumor-infiltrating and peripheral blood lymphocytes. In the first instance, tissue sections from 45 patients with histologically confirmed HL (Table 1) were stained for LAG-3. Patients were chosen solely on the basis of availability of tissue. There were no significant differences in age, sex, or EBV tissue status between this subgroup and the total group of patients: mean, 32 years (subgroup) versus 32 years (total); 40% females versus 38%; and 37% EBV-positive HL versus 37%, respectively. LAG-3 staining on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was both at the cell surface and cytoplasmic. LAG-3 predominantly stained lymphocytes present in those areas that were rich in HRS cells (Figure 1A). For each tissue section, the mean percentage of LAG-3–expressing cells as a proportion of all cells was calculated from 5 representative areas visualized using a 40× objective. Results were then graded in a semiquantitative manner as a percentage of non-HRS cells within the areas that were positive for LAG-3. A summary of this analysis is presented in Table 2. Intratumoral LAG-3 staining was observed in classic and nodular lymphocyte predominant HL. We also noticed an association between LAG-3 expression and HL histology. HL with mixed cellularity (MC) and lymphocyte-rich (LR) histology showed significantly higher frequency of LAG-3+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes than nodular sclerosing (NS) HL (P = .013). In agreement with the known association between EBV status and HL histology,1,3-5 we also observed an association between LAG-3 and EBV gene expression in tumor tissues (P = .023). In patients with remaining tissue samples (n = 33), immunohistochemistry for the forkhead transcription factor FOXP3 was performed. In agreement with the findings of Alvaro and colleagues,20 we observed distinct intranuclear staining within lymphocytes, with variation of expression between patient samples. Lymphocytes more frequently expressed LAG-3 than FOXP3 (P < .001, Wilcoxon matched pairs test) (Table 2). Dual staining for FOXP3 and LAG-3 showed that most tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes did not express both proteins (Figure 1B). No association was found between FOXP3 expression and histology (P = .489), EBV status (P = .833), or LAG-3 (P = .404).

Expression of LAG-3 by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in malignant HL lymph nodes

Case no. . | Disease status . | Age at diagnosis, y/sex . | Histology . | LAG-3+ cells in HRS-positive regions* . | EBV tissue status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ND | 45/F | MC | +++ | Negative |

| 8 | ND | 30/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 18 | RL | 44/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 22 | Remission | 48/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 28 | ND | 21/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 31 | ND | 76/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 32 | ND | 30/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 33 | ND | 26/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 35 | ND | 48/F | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 36 | RL | 34/F | NS | - | Positive |

| 38 | Remission | 33/M | NS | - | Positive |

| 40 | ND | 25/M | NS | + | Positive |

| 44 | ND | 22/F | NS | + | Positive |

| 47 | ND | 29/M | MC | ++ | Negative |

| 48 | Remission | 35/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 49 | ND | 45/F | MC | ++ | Negative |

| 50 | Remission | 21/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 51 | RL | 25/F | NS | - | Negative |

| 53 | ND | 22/M | MC | ++ | Positive |

| 54 | Remission | 24/F | NS | - | Negative |

| 55 | Remission | 42/M | NLP | + | Negative |

| 56 | ND | 20/M | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 57 | ND | 21/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 64 | ND | 43/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 65 | RL | 56/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 67 | ND | 13/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 69 | RL | 34/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 70 | ND | 24/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 71 | RL | 31/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 72 | ND | 26/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 74 | ND | 34/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 76 | ND | 23/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 77 | ND | 36/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 78 | ND | 21/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 79 | ND | 26/M | NS | +++ | Positive |

| 80 | ND | 34/M | LR | +++ | Negative |

| 81 | ND | 28/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 82 | ND | 36/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 83 | ND | 29/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 84 | ND | 23/F | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 85 | ND | 59/M | NS | +++ | Negative |

| 86 | ND | 20/M | NLP | ++ | Negative |

| 88 | ND | 19/F | NS | - | Negative |

Case no. . | Disease status . | Age at diagnosis, y/sex . | Histology . | LAG-3+ cells in HRS-positive regions* . | EBV tissue status . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | ND | 45/F | MC | +++ | Negative |

| 8 | ND | 30/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 18 | RL | 44/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 22 | Remission | 48/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 28 | ND | 21/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 31 | ND | 76/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 32 | ND | 30/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 33 | ND | 26/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 35 | ND | 48/F | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 36 | RL | 34/F | NS | - | Positive |

| 38 | Remission | 33/M | NS | - | Positive |

| 40 | ND | 25/M | NS | + | Positive |

| 44 | ND | 22/F | NS | + | Positive |

| 47 | ND | 29/M | MC | ++ | Negative |

| 48 | Remission | 35/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 49 | ND | 45/F | MC | ++ | Negative |

| 50 | Remission | 21/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 51 | RL | 25/F | NS | - | Negative |

| 53 | ND | 22/M | MC | ++ | Positive |

| 54 | Remission | 24/F | NS | - | Negative |

| 55 | Remission | 42/M | NLP | + | Negative |

| 56 | ND | 20/M | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 57 | ND | 21/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 64 | ND | 43/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 65 | RL | 56/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 67 | ND | 13/F | MC | +++ | Positive |

| 69 | RL | 34/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 70 | ND | 24/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 71 | RL | 31/F | NS | + | Negative |

| 72 | ND | 26/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 74 | ND | 34/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 76 | ND | 23/M | NS | + | Negative |

| 77 | ND | 36/M | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 78 | ND | 21/M | NS | - | Negative |

| 79 | ND | 26/M | NS | +++ | Positive |

| 80 | ND | 34/M | LR | +++ | Negative |

| 81 | ND | 28/M | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 82 | ND | 36/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 83 | ND | 29/F | NS | ++ | Negative |

| 84 | ND | 23/F | NS | ++ | Positive |

| 85 | ND | 59/M | NS | +++ | Negative |

| 86 | ND | 20/M | NLP | ++ | Negative |

| 88 | ND | 19/F | NS | - | Negative |

There was a significant correlation between percent LAG-3 staining and MC and/or LR histology versus NS (r = 0.555, P < .001) and between LAG-3 and positive EBV status (r = 0.31, P = .036).

ND indicates newly diagnosed; MC, mixed cellularity; NS, nodular sclerosing); RL, relapsed; Remission, long-term remission; NLP, nodular lymphocyte predominant; and LR, lymphocyte rich.

Percentage of non-HRS cells within HRS-rich areas that are positive for LAG-3; +++ indicates 74% to 50%; ++, 49% to 25%; +, 24% to 10%; -, less than 10%.

Tumor biopsy samples. (A) Representative photomicrographs of HL tumor biopsy samples from different histologic subtypes ([i-iii] MC, NS, and NLP, respectively). The EBV status of tumor tissues was confirmed by EBER in situ hybridization (iv-vi) and LMP1 immunohistochemistry (viii-x). Tissue samples shown in panels iv, v, viii, and ix were positive, while vi and x were negative for EBV. (xii-xiv) LAG-3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HL biopsies. The numbers of LAG-3+ cells in each tissue section were graded as described in Table 2. The tissue sections were graded +++ (xii), ++ (xiv), and negative (xiii). The relevant isotype controls are shown in panels vii, xi, and xv. (i-iii) Original magnification, × 10; (iv-xv) original magnification, × 40. (B) Representative lymph node sections from a patient with lymphocyte-rich EBV-positive classic HL. (i-ii) LAG-3 and FOXP3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, respectively; (iii) dual staining illustrates that the nuclear FOXP3 protein (red) and surface/cytoplasmic LAG-3 protein (brown) do not generally colocalize within the same lymphocyte. Photomicrographs were taken using a Nikon Coolpix 5700 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and were acquired with Microsoft Office XP Photo Editor (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Images were originally magnified under an Olympus CX41 microscope equipped with a 10×/0.65 NA (i-iii) or a 40×/0.25 NA (iv-xv) objective lens (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Tumor biopsy samples. (A) Representative photomicrographs of HL tumor biopsy samples from different histologic subtypes ([i-iii] MC, NS, and NLP, respectively). The EBV status of tumor tissues was confirmed by EBER in situ hybridization (iv-vi) and LMP1 immunohistochemistry (viii-x). Tissue samples shown in panels iv, v, viii, and ix were positive, while vi and x were negative for EBV. (xii-xiv) LAG-3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HL biopsies. The numbers of LAG-3+ cells in each tissue section were graded as described in Table 2. The tissue sections were graded +++ (xii), ++ (xiv), and negative (xiii). The relevant isotype controls are shown in panels vii, xi, and xv. (i-iii) Original magnification, × 10; (iv-xv) original magnification, × 40. (B) Representative lymph node sections from a patient with lymphocyte-rich EBV-positive classic HL. (i-ii) LAG-3 and FOXP3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, respectively; (iii) dual staining illustrates that the nuclear FOXP3 protein (red) and surface/cytoplasmic LAG-3 protein (brown) do not generally colocalize within the same lymphocyte. Photomicrographs were taken using a Nikon Coolpix 5700 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and were acquired with Microsoft Office XP Photo Editor (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Images were originally magnified under an Olympus CX41 microscope equipped with a 10×/0.65 NA (i-iii) or a 40×/0.25 NA (iv-xv) objective lens (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

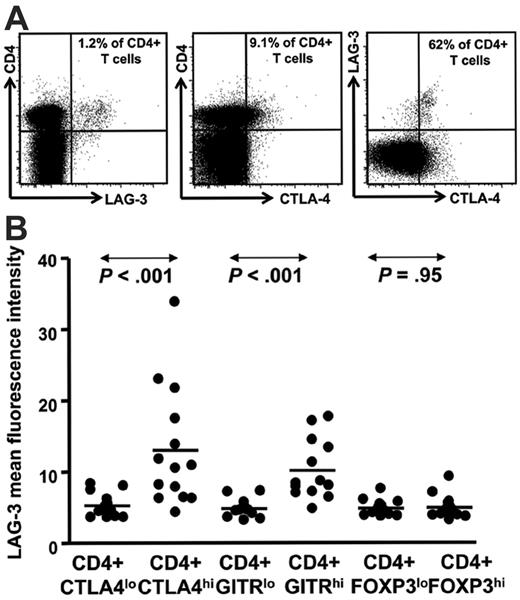

Circulating CD4+LAG-3hi cells are elevated in HL patients with active disease

Having demonstrated that LAG-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were prominent within HL lymph nodes, we next determined whether cells with the phenotype of Treg cells and LAG-3 were also present in the peripheral blood from patients with HL. PBMCs from patients with HL were costained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, CD45RO, and LAG-3. This allowed identification of CD4+ CD3+ and CD8+ CD3+ T-cell subsets and CD4+ CD25hi CD45ROhi Treg cells. In addition, PBMCs were also stained for intracellular CTLA-4 (cytolytic T lymphocyte antigen-4), FOXP3, and GITR (glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor family–related gene), which are expressed by various subsets of Treg cells.41,42 A representative flow cytometric plot showing LAG-3+ CD4+ T cells from one patient in remission is presented in Figure 2A. To determine the distribution of LAG-3+ CD4+ T cells within the conventional Treg cell population, we analyzed PBMC samples from a total of 12 newly diagnosed/relapsed (ND/RL) HL (prior to therapy) and 2 patients in long-term remission (for CTLA-4 and GITR) and 4 ND/RL (prior to therapy) and 10 remission HL patients (for FOXP3). A summary of data from these patients is presented in Figure 2B. We observed that LAG-3+ cells were enriched within intracellular CTLA-4hi and GITRhi CD4+ T cells but not within FOXP3 CD4+ T cells. These data strongly suggest that LAG-3 is expressed differentially within different subsets of Treg cells and is in accordance with our observation that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes do not coexpress LAG-3 and FOXP3. We analyzed CD4+ CD3+ and CD8+ CD3+ T-cell subsets in 16 patients with ND/RL and 28 in long-term remission. The proportions of these subsets did not vary between patients with ND/RL HL and those in long-term remission (data not shown).

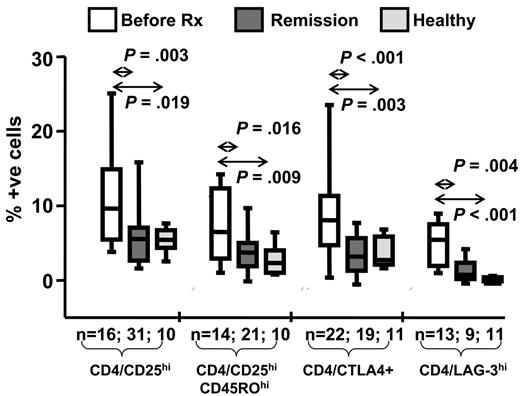

In the next set of analyses we compared the frequency of different Treg cell subsets in the peripheral blood from patients with ND/RL HL and those in long-term remission. A summary of this analysis is presented in Figure 3. The most striking observation was that all different subsets of Treg cells expressing conventional markers or CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells were consistently elevated in patients with ND/RL HL when compared with the PBMCs from patients in long-term remission and with 11 randomly selected healthy laboratory subjects (7 female, 4 male; mean age, 37 years; range, 22 to 47 years). Taken together these data strongly suggest that during active HL there is a significant expansion of Treg cells both at the tumor site and in the peripheral blood. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that this expansion may significantly impair antigen-specific T-cell responses.

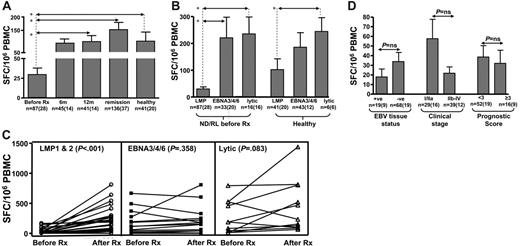

Ex vivo latent membrane protein epitope–specific T-cell functional responses are impaired at diagnosis in HL patients

To explore the potential effect of Treg cells on the antigen-specific CD8+ memory T-cell response, we longitudinally monitored EBV-specific T-cell responses in a large cohort of HL patients and healthy virus carriers using interferon-γ (IFN-γ) ELISPOT and MHC-peptide pentamer assays. These cohorts included 94 HL patients (newly diagnosed/relapsed and long-term remission; Table 1) and 29 healthy virus carriers. For ELISPOT assays, we used a panel of HLA class I–restricted CD8+ T-cell epitopes derived from either latent (LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6) or lytic (BZLF1 and BMLF1) proteins. The detailed data from these ELISPOT analyses are presented in Table 3 and Figure 4. Table 3 and Figure 4A represent a cross-sectional analysis allowing comparison between patients with ND/RL HL at different time points and long-term remission and healthy EBV-seropositive subjects. The number of assays performed at each time point reflects the HLA class I type and availability of blood from each patient. These analyses revealed that ND/RL HL patients with active disease (ie, prior to therapy) displayed a selective loss of IFN-γ expression by CD8+ T cells specific for LMP1/2 epitopes when compared with CD8+ T-cell responses from patients in long-term remission and healthy virus carriers (P < .001, P = .002, respectively). These results were confirmed by sequentially following a given LMP1/2 peptide–specific CD8+ T-cell response in individual ND/RL HL patients from before therapy to after therapy. (Figure 4C). In this matched-pair analysis, a significant increase in the LMP1/2 epitope–specific CD8+ T-cell response was observed in these patients following recovery from active HL (P < .001). In contrast, T-cell responses to the epitopes derived from EBNA3/4/6 and lytic antigens showed no impairment during active HL when compared with the responses observed following completion of therapy or from patients in long-term remission or healthy virus carriers (Table 3; Figure 4C). The overall hierarchy of T-cell responses toward latent and lytic antigens in HL patients was quite similar to those seen in healthy virus carriers (lytic > EBNA3/4/6 > LMP1/2; Figure 4B).

Ex vivo longitudinal profiling of EBV-specific T-cell responses in HL patients and healthy individuals using ELISPOT assays

EBV antigen, patient group . | No. of assays . | Mean SFCs (SE)* . | Median SFCs (IQR)* . | P vs pretherapy . | P vs 6 mo . | P vs 12 mo . | P vs long-term remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMP1/2A | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 87 | 30 (8) | 0 (0-24) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 45 | 87 (24) | 0 (0-106) | .091 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 41 | 101 (25) | 27 (0-169) | .014† | .494 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 136 | 153 (33) | 30 (0-176) | < .001† | .07 | .387 | — |

| Healthy | 41 | 102 (40) | 32 (0-94) | .002† | .329 | .996 | .442 |

| EBNA3/4/6 | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 33 | 221 (77) | 58 (0-187) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 21 | 149 (42) | 60 (40-178) | .651 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 24 | 351 (93) | 135 (8-135) | .190 | .311 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 39 | 290 (74) | 106 (14-106) | .258 | .582 | .645 | — |

| Healthy | 43 | 186 (54) | 60 (0-195) | .941 | .621 | .144 | .247 |

| Lytic | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 16 | 235 (63) | 175 (0-476) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 10 | 389 (165) | 128 (49-916) | .6 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 13 | 631 (161) | 506 (35-1187) | .076 | .515 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 23 | 304 (78) | 194 (80-294) | .568 | .71 | .122 | — |

| Healthy | 6 | 245 (51) | 254 (116-367) | .606 | .492 | .237 | .536 |

EBV antigen, patient group . | No. of assays . | Mean SFCs (SE)* . | Median SFCs (IQR)* . | P vs pretherapy . | P vs 6 mo . | P vs 12 mo . | P vs long-term remission . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMP1/2A | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 87 | 30 (8) | 0 (0-24) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 45 | 87 (24) | 0 (0-106) | .091 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 41 | 101 (25) | 27 (0-169) | .014† | .494 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 136 | 153 (33) | 30 (0-176) | < .001† | .07 | .387 | — |

| Healthy | 41 | 102 (40) | 32 (0-94) | .002† | .329 | .996 | .442 |

| EBNA3/4/6 | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 33 | 221 (77) | 58 (0-187) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 21 | 149 (42) | 60 (40-178) | .651 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 24 | 351 (93) | 135 (8-135) | .190 | .311 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 39 | 290 (74) | 106 (14-106) | .258 | .582 | .645 | — |

| Healthy | 43 | 186 (54) | 60 (0-195) | .941 | .621 | .144 | .247 |

| Lytic | |||||||

| ND/RL pretherapy | 16 | 235 (63) | 175 (0-476) | — | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 6 mo | 10 | 389 (165) | 128 (49-916) | .6 | — | — | — |

| ND/RL 12 mo | 13 | 631 (161) | 506 (35-1187) | .076 | .515 | — | — |

| Long-term remission | 23 | 304 (78) | 194 (80-294) | .568 | .71 | .122 | — |

| Healthy | 6 | 245 (51) | 254 (116-367) | .606 | .492 | .237 | .536 |

SE indicates standard error; IQR, interquartile range; —, not applicable.

Arithmetic mean and median values of γ-interferon—producing cells (referred to as spot-forming cells [SFCs] per 106 PBMCs) in response to HLA class 1—restricted LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6, and lytic antigen peptide epitopes.

Significant P value.

LAG-3 is enriched within the CD4+ T cells expressing intracellular CTLA-4hi and GITRhi. (A) Representative data from an HL patient in remission showing LAG-3 staining and (B) HL patient PBMC samples (n = 14) showing mean fluorescence intensity for LAG-3 on CD4+ T cells with intracellular CTLA-4lo and CTLA-4hi and GITRlo and GITRhi cells. P values were generated using the Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

LAG-3 is enriched within the CD4+ T cells expressing intracellular CTLA-4hi and GITRhi. (A) Representative data from an HL patient in remission showing LAG-3 staining and (B) HL patient PBMC samples (n = 14) showing mean fluorescence intensity for LAG-3 on CD4+ T cells with intracellular CTLA-4lo and CTLA-4hi and GITRlo and GITRhi cells. P values were generated using the Wilcoxon matched pairs test.

Cross-sectional analysis of Treg cell subsets in HL patients. Box and whisker plots summarizing the percentages of the mean (horizontal bar), standard error (box), and standard deviation (whiskers) of Treg cells in HL patients at diagnosis, in remission, and in randomly chosen healthy laboratory controls. The percentage of positive cells with each phenotype is shown on the vertical axis, and the P value and number of samples are indicated above and below each plot, respectively. P values were generated using the Mann-Whitney test.

Cross-sectional analysis of Treg cell subsets in HL patients. Box and whisker plots summarizing the percentages of the mean (horizontal bar), standard error (box), and standard deviation (whiskers) of Treg cells in HL patients at diagnosis, in remission, and in randomly chosen healthy laboratory controls. The percentage of positive cells with each phenotype is shown on the vertical axis, and the P value and number of samples are indicated above and below each plot, respectively. P values were generated using the Mann-Whitney test.

Intriguingly, the loss of CD8+ T-cell responses to LMP1/2 epitopes during active HL was not associated with EBV tumor status (Figure 4D). Patients with EBV-negative and EBV-positive HL showed comparable loss of LMP1/2 T-cell responses. Furthermore, the loss of LMP1 and LMP2 CD8+ T-cell responses also showed no association with the clinical staging or prognostic score of the patients (Figure 4D). For both ND/RL patients prior to therapy and patients in remission, no difference was seen when ELISPOT responses against LMP1 were compared with LMP2 (data not shown). Unsurprisingly, similar results were seen in patients with active disease irrespective of whether they were newly diagnosed or relapsed (data not shown).

Mean and standard error of ex vivo EBV-specific IFN-γ spot-forming cells following stimulation with peptide epitopes (SFC/106 PBMC). Responses were assessed before therapy (Before Rx) and 6 months (6m) and 12 months (12m) following diagnosis. The “6m” and “12m” columns include only data from newly diagnosed patients who went on to attain remission. These responses were compared with HL patients in long-term remission and healthy seropositive individuals. Panels A-C show data irrespective of EBV-tumor status. In panels A-B and D, “n” refers to the number of assays performed, with the number of patients shown in parentheses. (A) A cross-sectional analysis of LMP1/2-specific ELISPOT responses in HL patients at different time points and in healthy virus carriers. (B) A comparison of T-cell responses directed toward LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6, and lytic epitopes in ND/RL HL patients and healthy virus carriers. (C) A matched-pair analysis of LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6, and lytic epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in HL patients both before and after receiving chemotherapy (Before Rx and After Rx). (D) LMP1/2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in ND/RL EBV-positive and EBV-negative HL patients and ELISPOT responses in ND/RL HL patients with respect to clinical stage and Hasenclever/Diehl International Prognostic Score. In panels A and B, asterisks denote statistical significance.

Mean and standard error of ex vivo EBV-specific IFN-γ spot-forming cells following stimulation with peptide epitopes (SFC/106 PBMC). Responses were assessed before therapy (Before Rx) and 6 months (6m) and 12 months (12m) following diagnosis. The “6m” and “12m” columns include only data from newly diagnosed patients who went on to attain remission. These responses were compared with HL patients in long-term remission and healthy seropositive individuals. Panels A-C show data irrespective of EBV-tumor status. In panels A-B and D, “n” refers to the number of assays performed, with the number of patients shown in parentheses. (A) A cross-sectional analysis of LMP1/2-specific ELISPOT responses in HL patients at different time points and in healthy virus carriers. (B) A comparison of T-cell responses directed toward LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6, and lytic epitopes in ND/RL HL patients and healthy virus carriers. (C) A matched-pair analysis of LMP1/2, EBNA3/4/6, and lytic epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in HL patients both before and after receiving chemotherapy (Before Rx and After Rx). (D) LMP1/2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in ND/RL EBV-positive and EBV-negative HL patients and ELISPOT responses in ND/RL HL patients with respect to clinical stage and Hasenclever/Diehl International Prognostic Score. In panels A and B, asterisks denote statistical significance.

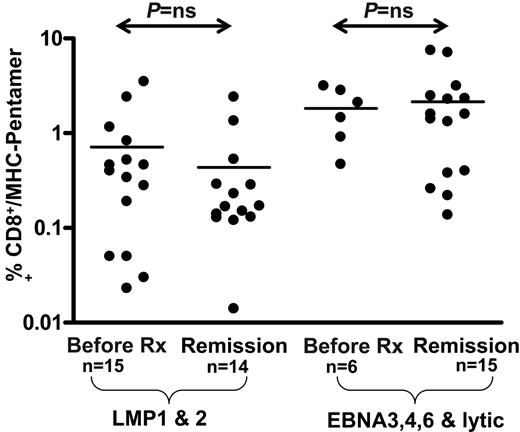

Ex vivo enumeration of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells using MHC-peptide pentamers in PBMCs from HL patients. The values shown on the logarithmic axis indicate the percentage CD8+ T cells positive for HLA class I–peptide pentamers. There was no significant difference in pentamer frequencies between EBV-positive HL and EBV-negative HL cases.

Ex vivo enumeration of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells using MHC-peptide pentamers in PBMCs from HL patients. The values shown on the logarithmic axis indicate the percentage CD8+ T cells positive for HLA class I–peptide pentamers. There was no significant difference in pentamer frequencies between EBV-positive HL and EBV-negative HL cases.

Ex vivo enumeration of EBV-specific CD8+ T cells from HL patients shows no difference between active disease and remission

To determine whether the loss of LMP1 and LMP2 T-cell function was due to the deletion of T-cell precursors, we enumerated antigen-specific T cells in patients with HL using MHC-peptide pentamers. A summary of this analysis based on a cohort of patients with ND/RL HL in long-term remission and healthy virus carriers is presented in Figure 5. In contrast to the ELISPOT assays, HL patients with acute disease showed normal precursor frequencies of CD8+ T cells specific for LMP1/2 epitopes when compared with patients in long-term remission and healthy virus carriers (Figure 5). In agreement with the ELISPOT data, there was no significant difference in frequencies observed in EBV-positive and EBV-negative HL cases.

The level of LAG-3 and FOXP3 expression on the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is coincident with the loss of LMP1/2-specific T-cell function

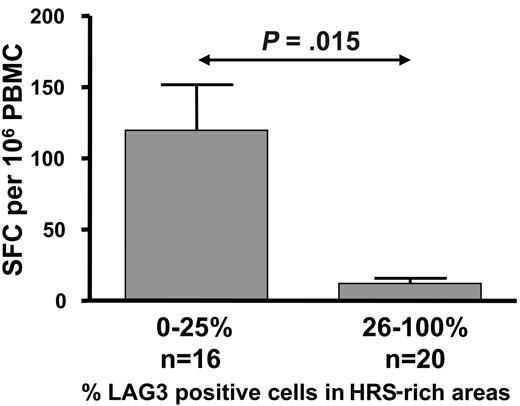

Taken together, our data suggest that the loss of IFN-γ production by LMP1- and LMP2-specific CD8+ T cells during active HL is due to a functional impairment, and this impairment might be related to the increased Treg cells in these patients. To explore this possibility we conducted an analysis to determine whether the level of LAG-3 and/or FOXP3 expression within HL lymph nodes is associated with loss of ex vivo IFN-γ production by LMP1- and LMP2-specific CD8+ T cells. This analysis revealed that IFN-γ production by LMP1- and LMP2-specific CD8+ T cells in the peripheral blood was significantly impaired in HL patients whose tumor tissues showed high levels of LAG-3 and/or FOXP3 expression by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (26% to 100%) when compared with the tissues with low LAG-3 and/or FOXP3 expression (0% to 25%) (P = .015 and P = .027, respectively, Mann-Whitney test; Figure 6).

In vitro pre-exposure of PBMCs to supernatants from HRS cell lines induces expansion of Treg cells

In the next set of experiments, we assessed the effect of supernatants on the HRS cells on the expansion of Treg cells in vitro. Data presented in Figure 7A-B show that incubation of PBMCs with pooled supernatants from HRS cells resulted in 1.5- to 2-fold enhanced expansion of CD4+ CD3+ T cells staining with intracellular CTLA-4 and surface LAG-3 when compared with the PBMCs incubated with control culture medium. Following incubation for 3 days, overall cell numbers (as determined by trypan blue exclusion assay) and CD3+CD8+/CD3+CD4+ ratios remained unchanged (data not shown).

Depletion of CD4+ LAG-3 T cells from PBMCs pre-exposed to HRS cell line supernatant results in enhancement of LMP1/2-specific T-cell function

Previous studies have suggested that immunosuppressive cytokines secreted by HRS cells may contribute to the suppression of virus-specific T-cell function in HL patients. Consistent with this, data obtained from experiments from 3 healthy EBV seropositive subjects showed that LMP-specific IFN-γ responses to LMP2 peptides by ELISPOT assay in PBMCs exposed to HL line supernatants were significantly reduced as compared with matched controls (P = .008) (Figure 7C). To determine whether this effect is in part mediated by CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells, we depleted CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells from fresh PBMCs and from the enriched CD4+ LAG-3+ T-cell population that had been generated following incubation with HRS supernatant PBMCs. Purity of fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) cells ranged between 98% and 100%. As seen in Figure 7D, removal of CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells resulted in enhancement of LMP2-specific IFN-γ responses to LMP2 peptides.

Discussion

A number of phenotypic markers, including intracellular CTLA-4, GITR, CD25, and FOXP3, have been identified as Treg cell selective receptors.41-43 The categorization between regulatory T cells expressing different phenotypic markers may prove arbitrary, with the functional relationship between populations requiring clarification. Further complexity is generated by the expression of some of these markers in activated nonregulatory T-cell subsets. Recently, the CD4 homolog LAG-3 has been recognized as a marker of Treg cells and a mediator of their suppressive activity in a murine model.22 In this study, activated Treg cells had a 20- to 50-fold increase in LAG-3 mRNAexpression, compared with only modest (1.5- to 4-fold) increases in FOXP3, GITR, and CTLA-4. More importantly, CD4+CD25hi Treg cells from LAG-3–/– mice exhibited reduced regulatory activity, and ectopic expression of LAG-3 on CD4+ T cells conferred suppressor activity toward antigen-specific T cells. Recent studies have also indicated that FOXP3 may be essential but is not sufficient for the Treg cell–like suppressive activity.

Histograms showing mean and standard error demonstrating the association of intratumoral LAG-3 expression and LMP1/2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in ND/RL HL patients prior to therapy. ELISPOT responses were compared in patients categorized as either low (0% to 25%) or high (26% to 100%) LAG-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes within HL lymph nodes.

Histograms showing mean and standard error demonstrating the association of intratumoral LAG-3 expression and LMP1/2-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in ND/RL HL patients prior to therapy. ELISPOT responses were compared in patients categorized as either low (0% to 25%) or high (26% to 100%) LAG-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes within HL lymph nodes.

Effect of HRS cell line supernatant on LMP effector T-cell function and expansion of Treg cells in vitro. PBMCs from 5 different healthy subjects were cultured in supernatants from HRS cell lines (L1236, HDLM2, L428, L540) for 3 days (A-B). A fibroblast line supernatant and serum free culture media (SFCM) alone were used as negative controls. (C) An LMP2A peptide–specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay following 3-day incubation of PBMCs (from a healthy HLA-A2 EBV-seropositive subject) with supernatant from the L540 HL cell line. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments. (D) T-cell reactivity toward CLG epitope (HLA-A2 restricted, LMP2A) in PBMCs from 2 different HLA-A2–positive individuals (D1 and D2) with or without depletion of CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells. Data from fresh PBMCs and PBMCs cultured in HRS cell supernatant are shown.

Effect of HRS cell line supernatant on LMP effector T-cell function and expansion of Treg cells in vitro. PBMCs from 5 different healthy subjects were cultured in supernatants from HRS cell lines (L1236, HDLM2, L428, L540) for 3 days (A-B). A fibroblast line supernatant and serum free culture media (SFCM) alone were used as negative controls. (C) An LMP2A peptide–specific IFN-γ ELISPOT assay following 3-day incubation of PBMCs (from a healthy HLA-A2 EBV-seropositive subject) with supernatant from the L540 HL cell line. Results are representative of 3 separate experiments. (D) T-cell reactivity toward CLG epitope (HLA-A2 restricted, LMP2A) in PBMCs from 2 different HLA-A2–positive individuals (D1 and D2) with or without depletion of CD4+ LAG-3+ T cells. Data from fresh PBMCs and PBMCs cultured in HRS cell supernatant are shown.

We found LAG-3 was strongly expressed on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes present in proximity to the HRS cells, and the proportion of LAG-3–expressing lymphocytes correlated with the EBV status of the tumor. However, this may simply reflect the tendency of LAG-3 to be more highly expressed in MC and LR histologic subtypes than in NS, because the latter was less frequently shown to be EBV positive. More lymphocytes stained for LAG-3 than for FOXP3. This is consistent with the findings of Huang and colleagues22 in which activated Treg cells had a 20- to 50-fold increase in LAG-3 mRNA expression, compared with only modest (1.5- to 4-fold) increases in FOXP3. Ex vivo analysis of PBMCs from HL patients revealed that LAG-3+ cells were enriched within CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of intracellular CTLA-4hi and GITRhi but not FOXP3hi and that the number of Treg cells were elevated in ND/RL patients prior to therapy but returned to normal levels following attainment of remission. Furthermore, we also found that pre-exposure of PBMCs to the supernatants from HRS cell lines significantly increased the expansion of CD4+ CTLA-4hi and CD4+ LAG-3hi Treg cells. Pre-exposed PBMCs displayed functional impairment of LMP1/2 peptide–specific T cells as assessed by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that soluble product(s) from the HRS cells is released into the microenvironment of the diseased lymph node and may contribute to the enrichment of Treg cells within the lymph node and peripheral blood.

IFN-γ ELISPOT assays were performed on PBMCs from HL patients. Although this analysis was restricted to those patients with informative alleles, we minimized this limitation by using 29 different EBV peptides presented by a wide array of MHC class I–restricted alleles, such that 97% of our patient population had at least 1 informative allele (with a median of 7 informative HLA class I EBV-specific peptides per patient). An alternate approach would be to use pooled peptides spanning each individual EBV latent protein, thus enabling us to determine effector T-cell function irrespective of HLA restriction.44 Indeed, this methodology was used to map many of the LMP1/2 peptides used in this study.26

In line with our observation of elevated Treg cells prior to therapy, we also noted a selective impairment of LMP1/2-specific effector T-cell function in newly diagnosed or relapsed HL patients when compared with patients in remission and healthy EBV-seropositive individuals. In striking contrast, responses to the immunodominant EBNA3/4/6 and lytic proteins (which are not expressed by HRS cells) were unimpaired. Although the precise mechanism for this selective loss of T-cell function is unknown, it is possible that the presence of LMP-specific CD4+ Treg cells within diseased lymph nodes of HL patients may suppress the antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell function. Although impairment in LMP1/2 effector T-cell function was reduced in EBV-positive cases as compared with EBV-negative ones, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Paradoxically we showed that LMP1/2 effector T-cell functional impairment is proportional to the degree of both LAG-3 and FOXP3 staining in HL tissues, but only the former was associated with EBV tissue status. It should be emphasized that our analysis of LMP1/2-specific effector T-cell function was performed on the peripheral blood. This may not reflect LMP1/2 effector T-cell function at the tumor site, which may indeed be suppressed within EBV-positive lymph nodes to a greater extent than EBV-negative tumors. Interestingly, previous groups have been able to generate LMP1/2-specific CTLs from EBV-negative tumor biopsies,10,11 whereas generation from EBV-positive tumors has been consistently unsuccessful. Their findings suggest that a local inhibition of EBV-specific CTL response is involved in EBV-positive HL cases.

Ineffective immunity against HRS cells is most probably linked to the well-established cell-mediated immune deficiency present early in the disease (reviewed by Poppema and van den Berg45 ). It remains uncertain whether this immune deficiency predates oncogenesis and results in an increased susceptibility to HL or conversely is a consequence of malignancy itself. Our finding that HRS cells are implicated in the enrichment of Treg cells within the diseased lymph nodes (and most likely the peripheral circulation) implies that the drive to generate excess Treg cells is reversed once HRS cells are eradicated and is inconsistent with immune suppression mediated by Treg cells predating establishment of the tumor. Previous studies by Marshall and colleagues demonstrated distinct variability between HL patients in the extent to which HL infiltrating cells induced inhibition of PBMC responses.46 These observations are consistent with our finding that the loss of LMP-specific T-cell function was coincident with the increased intratumoral LAG-3 expression and are suggestive of a specific suppressive activity generated by Treg cells within the vicinity of HRS cells. Accumulating in vivo evidence suggests that antigen-specific Treg cells control the intensity of T-cell responses and influence the magnitude of memory to a variety of human persistent viruses, including HSV, HIV, and HCV.47-50 For EBV, it has been suggested that LMP1- and EBNA1-specific HLA class II–restricted peptide epitopes can selectively recruit regulatory T cells and impair antigen-induced IFN-γ production.46,51,52 The N-terminal sequence of LMP1 encodes a number of potential MHC class II–restricted epitopes that suppress T-cell responses in vitro.46,52 Similarly, CD4+ T-cell lines specific for EBNA1 epitopes suppress IL-2 secretion by EBNA1-specific effector T cells.51

Human in vitro experiments have shown that LAG-3 has high affinity for MHC class II molecules and down-regulates CD3 T-cell receptor mediated signaling,53,54 and blockade of LAG-3 mediated signaling induces enhanced activation of human CD8 T cells.55 The recognition that CD4+ LAG-3+ Treg cells and LMP1/2-specific CD8+ effector T cells appear to play pivotal but opposing roles in regulating host EBV-specific cell-mediated immune responses in HL patients has important implications for understanding the pathogenesis of EBV-positive HL. Preliminary results of EBV-specific CTL therapy in relapsed/refractory EBV-positive HL patients are encouraging13 and, taken together, our findings have important implications in the improved design of immunotherapeutic strategies to boost LMP1/2-specific CTL activity.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, June 6, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015164.

Supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (Australia), Queensland Cancer Fund, and the British Society for Haematology. M.K.G. is an NHMRC Clinical Research Fellow, and R.K. is an NHMRC Principal Research Fellow.

M.K.G. and E.L. contributed equally to this work.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

We thank our colleagues from the referring centers whose patients are included in this analysis. We also thank Ms Laurie Kear for her help in coordinating the clinical aspects of this study.

![Figure 1. Tumor biopsy samples. (A) Representative photomicrographs of HL tumor biopsy samples from different histologic subtypes ([i-iii] MC, NS, and NLP, respectively). The EBV status of tumor tissues was confirmed by EBER in situ hybridization (iv-vi) and LMP1 immunohistochemistry (viii-x). Tissue samples shown in panels iv, v, viii, and ix were positive, while vi and x were negative for EBV. (xii-xiv) LAG-3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HL biopsies. The numbers of LAG-3+ cells in each tissue section were graded as described in Table 2. The tissue sections were graded +++ (xii), ++ (xiv), and negative (xiii). The relevant isotype controls are shown in panels vii, xi, and xv. (i-iii) Original magnification, × 10; (iv-xv) original magnification, × 40. (B) Representative lymph node sections from a patient with lymphocyte-rich EBV-positive classic HL. (i-ii) LAG-3 and FOXP3 protein on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, respectively; (iii) dual staining illustrates that the nuclear FOXP3 protein (red) and surface/cytoplasmic LAG-3 protein (brown) do not generally colocalize within the same lymphocyte. Photomicrographs were taken using a Nikon Coolpix 5700 camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and were acquired with Microsoft Office XP Photo Editor (Microsoft, Seattle, WA). Images were originally magnified under an Olympus CX41 microscope equipped with a 10×/0.65 NA (i-iii) or a 40×/0.25 NA (iv-xv) objective lens (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/108/7/10.1182_blood-2006-04-015164/4/m_zh80190601600001.jpeg?Expires=1769086201&Signature=10Rep19wkh5VAtRn789II~96k5930rd9fbLNTs1spe0a4xkgiPhrEJulrZ8eYePYiWKxsIk8nVP3VN92yLKgGgyjLEg1Dmv9LHKggjEoQ20wcjx8y2Fw0YaYcrzfWVPc-Urd-qPMNXwezEDxrdX0E7ireSP~8cXEwrHb4SDzXHE9GV2yQ~CocT4jhOBo2AbpBg-kCbt6FhLJF6JSMw6LN3WUKS0rCCVaJXIGdCtjLSaToWdznEAhysvuiBTaZ5A0s-ZO3RnZlaSQ4re97Q2EfGkheBteLvU-zGYIRR77we-XavHTMl1sCXvXa9okBK-HkPikZqOeVJ5NCGfS7LSNrg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal