Chronic immune activation plays a major role in AIDS pathogenesis. Biancotto and colleagues compared freshly excised lymph nodes from chronically HIV-1–infected patients and uninfected individuals. The authors describe a vicious cycle of self-enhancing activation.

Although it has been documented that primary infection with human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) rapidly destroys the bulk of the body's CD4+ memory T cells, especially in extralymphoid tissues, naive and most central memory T cells are initially spared and the immune system retains its regenerative capacity. However, ongoing viral replication and persistent hyperactivation in lymph nodes are thought to slowly erode the functional organization of these organs, reducing the immune system's regenerative capacity, facilitating viral evolution, and ultimately resulting in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).1,2 It is unclear what causes such hyperactivation and how it drives disease progression. To address these questions, it is necessary to quantify the cellular and cytokine profiles in secondary lymphoid organs and associate their dynamics with manifestations of structural and functional deterioration.

Applying a previously developed method of culturing lymphoid tissue that retains its complex structure,3 Biancotto and colleagues measured a reduced fraction of CD4+ T cells in cultured lymph nodes from chronically HIV-1–infected patients, as expected, but also a dramatic reduction in the representation of dendritic cells, which they suggest may interfere with the capacity to mount immune responses. Given that in the chronic phase, patients generally respond quite normally to common pathogens, the ability to specifically recruit antigen-presenting cells to lymph nodes of infected individuals on an ad hoc basis may remain largely intact, despite the chronic depletion. The authors also found that the frequency of memory and naive CD4 and CD8 T cells expressing the activation marker CD38 was elevated in lymph nodes from HIV-infected patients and suggest that such “activation” of naive cells might explain their impaired expansion response. Indeed, while naive (and memory) cells that are chronically stimulated below the threshold of full activation might become nonresponsive to subsequent stimulation by their cognate antigens, the authors' interpretation is confounded by the fact that a significant fraction of naive T cells normally expresses CD38. This reservation applies also to the argument that the clonal diversity of activated cells implied by the broad activation of naive cells proves that T-cell activation in the lymph nodes of HIV-1–infected persons is the result of exposure of bystander cells to cytokines (or other broad activating signals) rather than of T-cell receptor engagement. Yet, it is conceivable that bystander activation should be enhanced by proinflammatory factors and cytokines. Indeed, the authors demonstrated profound perturbations in the levels of cytokines. They describe a vicious cycle, whereby activated cells are the source of cytokines that in turn activate new cells. This cycle may be embedded in a somewhat more general scheme including positive and negative feedback effects, as well as amplification of effector memory T cells (and of apoptosis) due to the rapid, transient proliferation and differentiation of activated cells2 (see figure). Thus, the higher proportion of lymph node T cells with effector-memory phenotype, reported here and elsewhere, may primarily be the result of increased turnover.

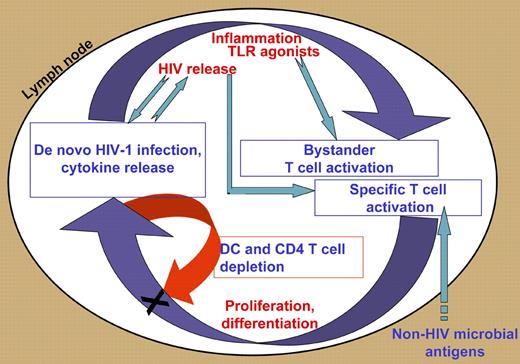

Interacting positive and negative feedback loops promote and control chronic activation in HIV-1–infected lymph nodes. T cells are specifically activated by HIV and other microbial antigens, and nonspecifically, as bystanders, by cytokines and other factors associated with inflammation, including Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists. Such activation leads to proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine secretion; the latter contribute to inflammation and bystander activation (positive feedback). Different effector cells secrete inhibitory cytokines and apoptosis-inducing factors that may affect T cells and dendritic cells (negative feedback). Also depicted are ongoing cycles of infection that connect to both feedback loops.

Interacting positive and negative feedback loops promote and control chronic activation in HIV-1–infected lymph nodes. T cells are specifically activated by HIV and other microbial antigens, and nonspecifically, as bystanders, by cytokines and other factors associated with inflammation, including Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists. Such activation leads to proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine secretion; the latter contribute to inflammation and bystander activation (positive feedback). Different effector cells secrete inhibitory cytokines and apoptosis-inducing factors that may affect T cells and dendritic cells (negative feedback). Also depicted are ongoing cycles of infection that connect to both feedback loops.

Are the changes in the cellular and cytokine profiles in secondary lymphoid organs truly “abnormal,” or are they essentially reversible manifestations of immune activation and its physiological controls? To what extent do they reflect irreversible tissue destruction and loss of function? A better understanding of these issues may reveal, in the authors' words, “new targets for immune-based interventions to slow HIV-1 disease progression.” The methodology used here provides opportunities for experimental manipulations in human lymphoid tissue aimed to normalize “abnormal” profiles and to identify irreversible damage.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ▪

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal