Abstract

Accumulating data have shown that the microenvironment of dendritic cells modulates subtype differentiation and CD1 expression, but the mechanisms by which exogenous factors confer these effects are poorly understood. Here we describe the dependence of CD1a− monocyte-derived dendritic cell (moDC) development on lipids associated with the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor–gamma (PPARγ). We also show the consecutive differentiation of immature CD1a−PPARγ+ moDCs to CD1a+PPARγ− cells limited by serum lipoproteins and terminated by proinflammatory cytokines. Immature CD1a− moDCs possess higher internalizing capacity than CD1a+ cells, whereas both activated subtypes have similar migratory potential but differ in their cytokine and chemokine profiles, which translates to distinct T-lymphocyte–polarizing capacities. CD1a+ moDCs stand out by their capability to secrete high amounts of IL-12p70 and CCL1. As lipoproteins skew moDC differentiation toward the generation of CD1a−PPARγ+ cells and inhibit the development of CD1a+PPARγ− cells, we suggest that the uptake of lipids results in endogenous PPARγ agonists that induce a cascade of gene transcription coordinating lipid metabolism, the expression of lipid-presenting CD1 molecules, subtype dichotomy, and function. The presence of CD1a−PPARγ+ and CD1a+PPARγ− DCs in lymph nodes and in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis confirms the functional relevance of these DC subsets in vivo.

Introduction

Human dendritic cells (DCs) represent a rare and heterogeneous population of cells that originate from CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells. Myeloid DCs differentiate from a common progenitor along 2 independent pathways that give rise to CD11c+ blood precursors with or without the expression of membrane CD1a.1,2 CD11c+CD1a+ DCs differentiate to Langerhans cells (LCs) in the epidermis and other epithelial surfaces, whereas the CD11c+CD1a− subtype replenishes various tissues with interstitial/tissue DCs.3,4 DCs also differentiate from monocytes in peripheral tissues driven by microenvironmental factors generated by inflammation or various metabolic changes.5-7 Immature myeloid DCs act as sensors of their actual milieu and transmit this information to peripheral lymphoid tissues where they relay it to T lymphocytes.8

CD1a belongs to type 1 CD1 membrane proteins widely used as human DC markers expressed early in their development.9 Functional CD1a has to be stabilized by captured self-derived or pathogen-derived lipids10 to activate CD1-restricted T lymphocytes.11-13 In contrast to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules, the membrane expression of CD1a does not depend on DC maturation,14 but little is known about the transcriptional and/or ligand-dependent regulation of this process.

In vitro differentiation of CD34+ progenitors to both CD1a− and CD1a+ DCs requires granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulatory factor (GM-CSF) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α),15 whereas culturing blood monocytes in the presence of interleukin-4 (IL-4) and GM-CSF is an efficient method to obtain large numbers of DCs16,17 that resemble immature tissue DCs.18 Complementing these cultures with transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)19 or substitution of IL-4 by TNF-α directs moDC differentiation to both CD1a− and CD1a+ DCs.20 Other studies reported that the serum concentration of culture media can also influence CD1a+ and CD1a− dichotomy and modify the functional properties of these DC subsets.21-23 The nature of exogenous factors or regulatory pathways that may modulate the ratio of CD1a+ and CD1a− moDCs has not been identified.

In this study we show that CD14high monocytes cultured with GM-CSF and IL-4 in AIMV medium differentiate to CD14lowCD1a− and CD14−CD1a+ DCs through consecutive steps of differentiation. CD1a− and CD1a+ cells differ in their internalizing capacity, cytokine and chemokine profiles, and T-lymphocyte–polarizing potential but possess similar T-lymphocyte–activating capacities. Remarkably, in vitro development of CD1a− moDCs was associated with the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor–gamma (PPARG) gene, whereas removal of lipoproteins skewed moDC differentiation toward CD1a+ cells. These results suggest a link between lipoprotein-mediated modulation of moDC subtype differentiation, PPARγ activation, and the function of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells. Furthermore, monitoring CD1a−/CD1a+ moDC ratios in the context of serum-lipid parameters may uncover new aspects of the interplay between lipid homeostasis and immunity.

Materials and methods

Dendritic-cell cultures

Monocytes were isolated from buffy coats by Ficoll gradient centrifugation (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden) and immunomagnetic cell separation using anti-CD14–conjugated microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). After magnetic separation, 90% to 95% of the cells were CD14+ monocytes as measured by flow cytometry. Monocytes were cultured in 6-well tissue-culture plates at a density of 2 × 106 cells/mL in AIMV medium supplemented with 75 ng/mL GM-CSF (Leucomax; Gentaur Molecular Products, Brussels, Belgium) and 100 ng/mL IL-4 (Peprotech EC, London, United Kingdom). In some experiments, monocytes were cultured in RPMI supplemented with cytokines and 10% human AB serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), lipoprotein-depleted FBS (LPDS), or purified lipoproteins (Intracel, Frederick, MD) or RPMI supplemented with 1.0 mg/mL bovine insulin, 0.55 mg/mL human transferrin, and 0.5 μg/mL sodium selenite (RPMI+1% ITS; Sigma-Aldrich). At day 2, the same amount of GM-CSF and IL-4 was added and the cells were cultured for another 3 days (day 5) or longer as indicated. Immature DCs were activated at day 5 of culture either with an inflammatory cocktail containing 10 ng/mL TNF-α, 5 ng/mL IL-1β, 20 ng/mL IL-6 (Peprotech EC), and 1 μg/mL PGE2 (Sigma-Aldrich)24 or with soluble CD40 ligand (CD40L; Peprotech EC) or CD40L-expressing L293 cells. Untransfected L293 cells were used as controls. Activation was done using a 4:1 DC/CD40L-expressing L293 cell or DC/L-cell ratio. Activation signals were present for 24 hours unless indicated otherwise. MoDC differentiation in the presence of 5 mM rosiglitazone (RSG; Alexis Biochemicals, San Diego, CA) was performed as described previously.25 The effect of internalized human serum lipoproteins on CD1a expression was studied in moDCs generated in RPMI+1% ITS in the presence of 40 or 10 μg/mL lipoproteins added at days 0 and 2 of culture.

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

Phenotypic characterization of moDCs was performed by flow cytometry using different fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (anti-CD83–FITC, CD1a-PE, CD14-PE, CD40-PE, CD86-PE, HLA DR–PC5 [Beckman Coulter, Hialeah, FL] CD209-FITC, CD207-CyC [BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA] CD91-FITC [Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom] CCR7-PE [R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN]) or by using unlabeled antibodies to E-cadherin and LDL-R (R&D Systems) and FITC-conjugated F(ab′)2 goat anti–mouse Ig (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) as secondary antibody. Isotype-matched control antibodies were obtained from BD Pharmingen. Fluorescence intensities were measured by FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences Immunocytometry Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and data were analyzed using WinMDI freeware (Joseph Trotter, La Jolla, CA; http://flowcyt.salk.edu/software.html). CD1a-labeled moDCs were separated using the FACS DiVa high-speed cell sorter (BD Biosciences Immunocytometry Systems). Intracellular staining with IL-12–FITC (R&D Systems) and CD1a (BD Pharmingen) was done with the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm and PermWash reagents, according to the manufacturers' recommendations.

Internalization assays

Lucifer yellow (LY) uptake was measured by incubating 1 × 106 moDCs with 1 mg/mL LY (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 30 minutes. Mannose receptor–mediated endocytosis was measured by the uptake of 250 μg/mL FITC-dextran (Sigma-Aldrich) after 1-hour incubation at 37°C. Uptake of modified lipids was assessed by the uptake of DiI-labeled acetylated (acLDL) and oxidized LDL (oxLDL) particles (Intracel) after 4-hour incubation at 37°C. Phagocytosis was measured by the uptake of FITC-labeled Escherichia coli (generous gift from I. Andó, Biological Research Center, Szeged, Hungary) and FITC-conjugated 1-μm diameter carboxylate-modified latex beads (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were incubated with the bacteria for 6 hours and with the latex beads for 8 hours at 37°C. Control samples were treated similarly at 0°C. After incubation with the various exogenous materials, fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry.

Mixed-leukocyte cultures

Allogeneic monocyte-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cocultured with moDCs preactivated by CD40L-expressing fibroblasts or by control L293 cells at a 1:10 moDC/leukocyte ratio, and supernatants were collected at day 3. Primed T cells were then reactivated for 24 hours on plates coated with 5 μg/mL anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (mAb; BD Pharmingen). In some experiments, moDCs were activated by 5 μg/mL soluble CD40L, plated to 96-well plates at graded numbers, and incubated with a fixed number of leukocytes. T-lymphocyte proliferation was measured by [3H]-thymidine (1 μCi/well [0.037 MBq/well] Amersham Biosciences) incorporation at day 5, or supernatants were harvested and used for cytokine measurements.

Cytokine measurements

Culture supernatants of moDCs were harvested 16 hours after activation by CD40L and stored at −20°C. Cytokine pattern of CD40L-activated moDCs was analyzed using the RayBiotech cytokine protein array III (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) signals were detected by a Kodak 2000MM Image Station and quantitated by the Kodak 1D Image Analysis software (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Intensities of the spots corresponding to each cytokine were normalized to the mean intensity of the 6 internal control spots, and the relative normalized intensity of duplicate dots obtained from 4 independent CD1a− and CD1a+ sample pairs were calculated. Secreted cytokine concentrations were determined by the Inflammation Cytokine Bead Array (CBA) kit and by TGF-β enzyme immunoassay (ELISA; both from BD Pharmingen). Quantitation of CCL1 was performed by DuoSet ELISA (R&D Systems). Cell-culture supernatants were used at pretitrated dilutions and the assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluorescence intensities were measured with FACSCalibur cytometer, and the results were evaluated by the FCAP array software (Soft Flow, Pécs, Hungary). Culture supernatants of DC–T-cell cultures were harvested at day 3 of culture and stored at −20°C unless indicated otherwise. Concentrations of IFN-γ, IL-10, and IL-4 were measured using OptiEIA (BD Pharmingen). Statistical analysis was performed by paired t test (CCL1) or Wilcoxon signed rank test (IL-12, IL-10; *P < .05, **P < .001).

Real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (QRT-PCR)

Real-time PCR was done as described previously.25 Briefly, total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 30 minutes from 100 ng total RNA using Superscript II reverse transcriptase and random primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed (ABI PRISM 7900; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with 40 cycles at 95°C for 12 seconds and 30°C for 1 minute using Taqman assays. All PCR reactions were done in triplicates with 1 control reaction containing no RT enzyme. The comparative Ct method was used to quantify transcripts relative to the endogenous control gene 36B4. The 36B4 expression levels did not vary between cell types or treatments. The sequences of the primers and probes are available upon request.

IP stainings and double immunofluorescence (IF)

Immunostainings were carried out on human tissues obtained from formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded surgical specimens. The following antibodies were applied: monoclonal antibody (mAb) to PPARγ (E8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a dilution of × 1:75; mAb to DC-SIGN (× 1:50; BD Pharmingen); mAb to CD1a (× 1:15; Novocastra, Newcastle, United Kingdom); rabbit antibody to S100 protein (affinity purified; Novocastra). For immunoperoxidase (IP), we used standard ABC-based immunostaining as described earlier.26 Double IF for PPARγ in combination with other markers was carried out with sequential immunostaining. PPARγ was first detected with the tetramethyl-rhodamine (TMR)–conjugated tyramide reagent of the fluorescent amplification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (TSA-TMR system; Perkin Elmer Life Science, Boston, MA) to obtain red nuclear fluorescence. The second IF labeling with other markers was then made using a mixture of preincubated primary mAb plus biotinylated secondary IgG F(ab′)2 plus normal goat serum followed by streptavidin-FITC. As negative controls we used isotype-matched control IgG (Dako) in place of the primary antibodies. For PPARγ, we also used a blocking peptide–pretreated primary antibody to demonstrate specific staining. Positive controls for PPARγ staining were made on normal human adipose tissue where most of the nuclei of adipocytes expressed the protein (not shown). Microphotographs of tissue sections were taken using an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with excitation filters for green (FITC), red (rhodamine), and blue (DAPI) fluorescence and an Olympus DP50 digital camera (Olympus Europe, Hamburg, Germany) connected to a computer. For transferring and editing images for documentation, Viewfinder and Studio Lite software version 1.0.136 of 2001 Pixera (Pixera UK Digital Imaging Systems, Egham, Surrey, United Kingdom) and Adobe Photoshop version 8.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) were used. The microscope used the following objective lenses: Plan 4 ×/0.1 numerical aperture (NA), Plan 10 ×/0.25 NA, Plan 40 ×/0.65 NA, and Plan FI 100 ×/1.30 NA (oil).

Results

Phenotypic heterogeneity of in vitro–generated immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells

Previous results revealed that moDCs generated in vitro in AIMV medium substituted with GM-CSF and IL-4 give rise to a functionally competent homogeneous population of DCs appropriate for clinical utility.27 We have observed that under these conditions CD14high monocytes differentiate to both CD1a− and CD1a+ cells. The percentage of CD1a+ cells monitored in independent in vitro cultures of 87 blood donors substantially varied among individuals as summarized in Table 1 Individual differences could repeatedly be detected (± 5%) in DC cultures derived from blood samples taken on the same day. These results suggested that variations in CD1a+ and CD1a− moDC ratios, observed under standard culture conditions, might be attributed to in vivo–relevant regulatory pathways of moDC differentiation. To examine the functional significance of this variation and to minimize individual-to-individual variability, first we sought to compare the phenotypic and functional properties of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells derived from the same individual and the same culture.

Donor-dependent variation of monocyte-derived CD1a− and CD1a+ dendritic cell ratios measured in monocyte-derived dendritic-cell cultures

| Percentage of CD1a+ cells . | No. of individual in vitro cultures . | Percentage of CD1a+ cells, mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| 0%-20% | 11 | 11.8 (7.4) |

| 20%-40% | 28 | 30.3 (5.1) |

| 40%-60% | 29 | 49.8 (4.4) |

| 60%-80% | 14 | 72.1 (5.2) |

| 80%-100% | 5 | 87 (1.2) |

| Percentage of CD1a+ cells . | No. of individual in vitro cultures . | Percentage of CD1a+ cells, mean (SD) . |

|---|---|---|

| 0%-20% | 11 | 11.8 (7.4) |

| 20%-40% | 28 | 30.3 (5.1) |

| 40%-60% | 29 | 49.8 (4.4) |

| 60%-80% | 14 | 72.1 (5.2) |

| 80%-100% | 5 | 87 (1.2) |

For individual in vitro cultures, n = 87.

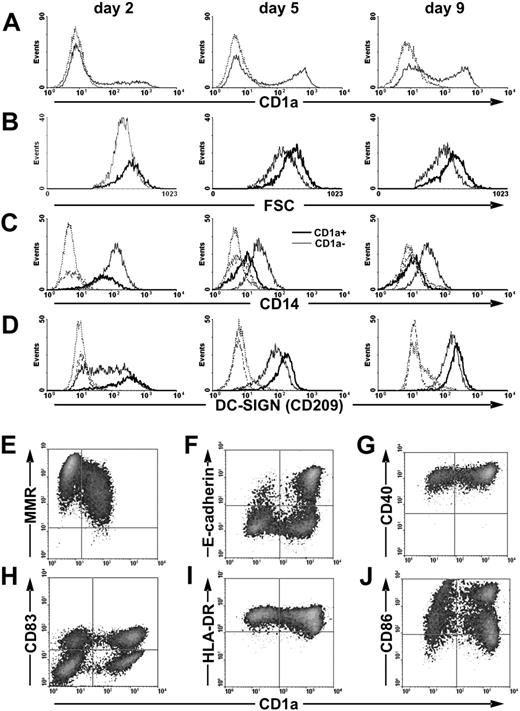

Kinetic studies revealed that CD1a+ cells appear early and differentiate simultaneously with CD1a− cells (Figure 1A). This differentiation pathway is accompanied by the continuous decrease and final loss of CD14 expression in the CD1a+ population in parallel with the generation of CD14lowCD1a− cells (Figure 1C). The DC-specific C-type lectin DC-SIGN/CD209 and CD40 are expressed by both subsets at similar levels (Figure 1D,G), but CD1a+ cells are distinguished by the lower expression of macrophage mannose receptor (MMR; Figure 1E) and the de novo expression of E-cadherin in a subpopulation of cells (Figure 1F). Activation of immature CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs by CD40L (data not shown) or by inflammatory stimuli (Figure 1H-J) results in mature CD83+ DCs characterized by high cell-surface expression of CD86 and HLA-DR. Taken together, these results suggest that CD1a− and CD1a+ cells either represent separate moDC subsets or correspond to distinct differentiation stages.

Differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells from monocytes. Phenotypic characterization of developing immature (A-G) and activated (H-J) moDCs. (A) Kinetics of CD1a membrane expression. Dotted line represents isotype control staining. (B) CD14high monocytes give rise to CD1a− and to CD1a+ cells of different forward light-scatter (FSC) related to cells' size. (C) The expression of CD14 divides moDCs to CD14lowCD1a− and CD14−CD1a+ cells. (D) Both CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs express the C-type lectin DC-SIGN. Thin line represents the CD1a− population, and bold line represents the CD1a+ population in panels B-D. Dotted line represents isotype control staining of the CD1a− population, and dashed-dotted line represents the same of the CD1a+ population in panels C-D. (E) On day 5 of culture, CD1a+ cells express slightly less MMR than CD1a− cells. (F) On day 5 of culture, a subpopulation of CD1a+ cells expresses E-cadherin. (G) On day 5 of culture, both CD1a− and CD1a+ cells are characterized by high CD40 expression. (H-J) Immature moDCs were activated by inflammatory cocktail on day 5 for 24 hours, and phenotypic analysis was performed on day 6 of culture. Both CD1a− and CD1a+ mature moDCs coexpress CD83, high levels of HLA-DR, and CD86.

Differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells from monocytes. Phenotypic characterization of developing immature (A-G) and activated (H-J) moDCs. (A) Kinetics of CD1a membrane expression. Dotted line represents isotype control staining. (B) CD14high monocytes give rise to CD1a− and to CD1a+ cells of different forward light-scatter (FSC) related to cells' size. (C) The expression of CD14 divides moDCs to CD14lowCD1a− and CD14−CD1a+ cells. (D) Both CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs express the C-type lectin DC-SIGN. Thin line represents the CD1a− population, and bold line represents the CD1a+ population in panels B-D. Dotted line represents isotype control staining of the CD1a− population, and dashed-dotted line represents the same of the CD1a+ population in panels C-D. (E) On day 5 of culture, CD1a+ cells express slightly less MMR than CD1a− cells. (F) On day 5 of culture, a subpopulation of CD1a+ cells expresses E-cadherin. (G) On day 5 of culture, both CD1a− and CD1a+ cells are characterized by high CD40 expression. (H-J) Immature moDCs were activated by inflammatory cocktail on day 5 for 24 hours, and phenotypic analysis was performed on day 6 of culture. Both CD1a− and CD1a+ mature moDCs coexpress CD83, high levels of HLA-DR, and CD86.

Differentiation of CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells from CD1a− precursors

Based on their larger size deducted from forward light-scatter intensity (Figure 1B) and decreased MMR expression (Figure 1E), CD1a+ cells may represent a more mature differentiation state than their CD1a− counterparts. To examine this scenario we sorted the CD1a− and CD1a+ subsets on day 5 of culture (Figure 2A) and recultured the separated cells in fresh AIMV medium for an additional 2 days in the presence of IL-4 and GM-CSF. In the absence of any activation stimuli, the sorted CD1a− cells generated a fraction of CD1a+ cells (Figure 2B, nonactivated), whereas the CD1a+ cell population remained homogenous, albeit the surface expression of CD1a increased. Importantly, when the sorted cells were recultured in the presence of an inflammatory cocktail, this differentiation process was blocked in both subsets (Figure 2B, activated). These results strongly support the notion that differentiation of CD1a− cells to CD1alow and later to CD1ahigh cells represents consecutive steps of moDC differentiation that can be terminated by inflammatory signals.

Differentiation of CD1a− monocyte-derived dendritic cells to CD1a+ cells. MoDCs were collected on day 5 of culture and sorted by flow cytometry to CD1a− and CD1a+ populations. (A) The expression of CD1a protein in the original and the sorted populations was monitored by flow cytometry. (B) The sorted CD1a− (left) and CD1a+ (right) cells were cultured in fresh AIMV medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4 without (nonactivated) and with inflammatory cocktail (activated). The ratio of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells in both cultures was measured on day 7 by flow cytometry. (C) Kinetics of mRNA expression during moDC differentiation measured by real-time QRT-PCR. Mean values and SD of triplicates are documented. (D) Membrane expression of CD1a protein in the moDC population monitored by flow cytometry. A typical experiment of 3 is documented.

Differentiation of CD1a− monocyte-derived dendritic cells to CD1a+ cells. MoDCs were collected on day 5 of culture and sorted by flow cytometry to CD1a− and CD1a+ populations. (A) The expression of CD1a protein in the original and the sorted populations was monitored by flow cytometry. (B) The sorted CD1a− (left) and CD1a+ (right) cells were cultured in fresh AIMV medium supplemented with GM-CSF and IL-4 without (nonactivated) and with inflammatory cocktail (activated). The ratio of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells in both cultures was measured on day 7 by flow cytometry. (C) Kinetics of mRNA expression during moDC differentiation measured by real-time QRT-PCR. Mean values and SD of triplicates are documented. (D) Membrane expression of CD1a protein in the moDC population monitored by flow cytometry. A typical experiment of 3 is documented.

As activation of immature DCs by inflammatory signals is known to induce a dramatic change in gene transcription and organization of the intracellular vesicular system,28 we monitored CD1a protein expression in the cell membrane parallel with CD1a mRNA levels. The results shown in Figure 2C show that CD1a expression is regulated at the mRNA level.

Internalization of exogenous material by monocyte-derived CD1a− and CD1a+ dendritic cells

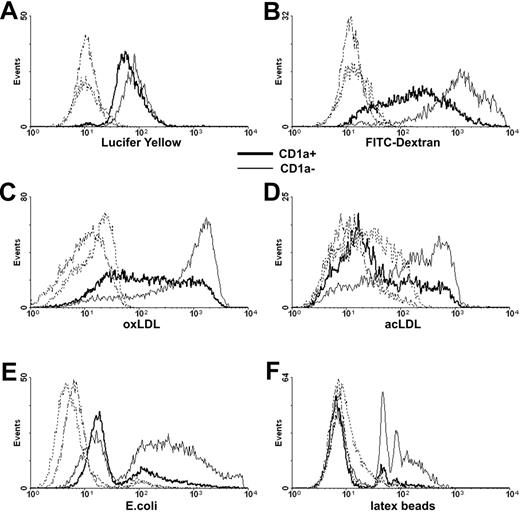

Immature moDCs play a pivotal role in antigen capture; they are highly phagocytic cells equipped with a large array of internalizing receptors.29 We found little difference in the pinocytosis of LY by CD1a+ and CD1a− moDCs (Figure 3A) but in correlation with their higher expression of MMR (Figure 1E), the uptake of dextran was more efficient by CD1a− than by CD1a+ cells (Figure 3B). The internalizing capacity of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells also differed when the uptake of formaldehyde-fixed E coli (Figure 3E), modified lipids (Figure 3C-D), or latex beads (Figure 3F) was measured.

Uptake of soluble material and particles by CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Monocyte-derived moDCs collected at day 5 of culture were incubated in the presence of fluorescein-labeled exogenous compounds and particles at 37°C, and internalization by CD1a− (thin line) and CD1a+ cells (bold line) was measured by flow cytometry. Control samples were treated similarly at +4°C (dashed lines). (A) Pinocytosis of Lucifer yellow and (B) uptake of FITC-labeled soluble dextran were measured after 1-hour incubation at 37°C. (C) The uptake of DiI-labeled oxLDL and (D) acLDL was measured after 4 hours. (E) Internalization of FITC-labeled paraformaldehyde-fixed E coli was measured after 8 hours. (F) Phagocytosis of YG-fluorescent carboxylate-modified latex beads was measured after 8 hours. Histograms (E-F) were normalized to equal numbers of nonphagocytic CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. Typical experiments of 3 are documented.

Uptake of soluble material and particles by CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Monocyte-derived moDCs collected at day 5 of culture were incubated in the presence of fluorescein-labeled exogenous compounds and particles at 37°C, and internalization by CD1a− (thin line) and CD1a+ cells (bold line) was measured by flow cytometry. Control samples were treated similarly at +4°C (dashed lines). (A) Pinocytosis of Lucifer yellow and (B) uptake of FITC-labeled soluble dextran were measured after 1-hour incubation at 37°C. (C) The uptake of DiI-labeled oxLDL and (D) acLDL was measured after 4 hours. (E) Internalization of FITC-labeled paraformaldehyde-fixed E coli was measured after 8 hours. (F) Phagocytosis of YG-fluorescent carboxylate-modified latex beads was measured after 8 hours. Histograms (E-F) were normalized to equal numbers of nonphagocytic CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. Typical experiments of 3 are documented.

Cytokine and chemokine production of monocyte-derived CD1a− and CD1a+ dendritic cells

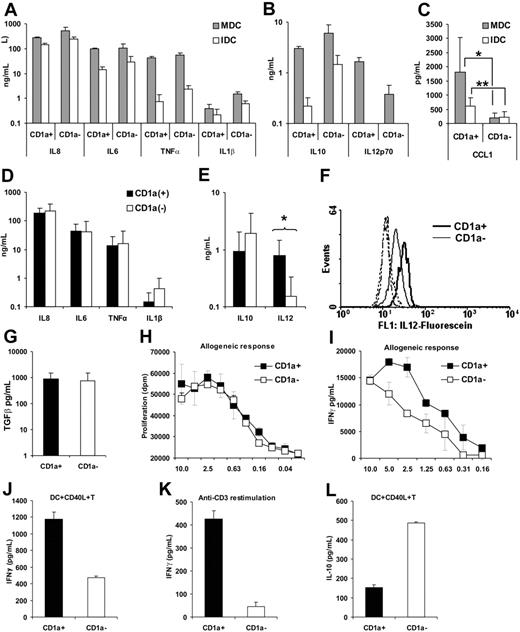

In contrast to inflammatory signals that induce activation and mobilization of DCs, stimulation through CD40L results in cytokine-producing cells.30 To obtain an overall picture on the cytokine and chemokine profile of the 2 moDC subsets, we first sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ cells from individual cultures and then activated the isolated cells by CD40L-expressing L293 fibroblasts. After 16 hours of culture, the supernatants were collected and subjected to cytokine analysis by the RayBio Cytokine Array III. Mean values ± SD of relative normalized intensities measured in 4 sample pairs showed that both CD1a− and CD1a+ DCs secreted proinflammatory cytokines, IL-12 and IL-10, and a set of chemokines listed in Table 2 Interestingly, CD1a+ cells secreted about 10-fold more I-309/CCL1 than their CD1a− counterparts (Table 2). The cytokine data were validated by measuring cytokine concentrations in the supernatants of immature and CD40L-activated DCs using the CBA assay (Figure 4A-B) or ELISA (Figure 4C,G). As described previously for immature LCs,31 both CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs constitutively secreted IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10, whereas CD40L-mediated stimulation induced a dramatic increase of TNF-α and IL-12 secretion (Figure 4A-B). The results summarized in Figure 4C-E,G show cytokine concentrations measured in the supernatants of CD40L-activated CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs isolated from 7 individuals. Statistical analysis of the data revealed that both immature (P < .001) and CD40L-activated (P = .014) CD1a+ moDCs secreted significantly more CCL1 than their CD1a− counterparts (Figure 4C). Activated CD1a+ moDCs also produced a higher level (P = .016) of IL-12p70 (Figure 4E) than CD1a− cells, whereas IL-10 secretion (Figure 4E) was higher in CD1a− cells (P = .078). MoDCs secreted TGF-β1 but no difference was found between cytokine levels produced by CD1a− and CD1a+ cells (Figure 4G).

Relative level of cytokines and chemokines secreted by CD1a+ and CD1a− monocyte-derived dendritic cells activated by CD40L

| . | CD1a+/CD1a− ratio, mean (SD) of relative normalized intensity . |

|---|---|

| Cytokine | |

| IL-6 | 1.1 (0.2) |

| IL-1β | 1.9 (1.7) |

| TNFα | 3.3 (3.7) |

| IL-12 | 3.1 (2.6) |

| Oncostatin M | 1.0 (0.4) |

| IL-10 | 0.9 (0.4) |

| Chemokine | |

| IL-8/CXCL8 | 1.1 (0.4) |

| GRO/CXCL1/2/3 | 1.7 (0.7) |

| I-309/CCL1 | 11.3 (4.5) |

| MIP-1δ/CCL15 | 0.6 (0.5) |

| RANTES/CCL5 | 0.9 (0.3) |

| MDC/CCL22 | 0.8 (0.3) |

| TARC/CCL17 | 0.8 (0.5) |

| . | CD1a+/CD1a− ratio, mean (SD) of relative normalized intensity . |

|---|---|

| Cytokine | |

| IL-6 | 1.1 (0.2) |

| IL-1β | 1.9 (1.7) |

| TNFα | 3.3 (3.7) |

| IL-12 | 3.1 (2.6) |

| Oncostatin M | 1.0 (0.4) |

| IL-10 | 0.9 (0.4) |

| Chemokine | |

| IL-8/CXCL8 | 1.1 (0.4) |

| GRO/CXCL1/2/3 | 1.7 (0.7) |

| I-309/CCL1 | 11.3 (4.5) |

| MIP-1δ/CCL15 | 0.6 (0.5) |

| RANTES/CCL5 | 0.9 (0.3) |

| MDC/CCL22 | 0.8 (0.3) |

| TARC/CCL17 | 0.8 (0.5) |

Cytokine secretion of CD40L-activated CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and cocultured activated allogeneic lymphocytes. Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ immature DCs (2 × 105) were cultured on a monolayer of CD40L (CD40L)–expressing L929 fibroblasts (0.4 × 105) in 24-well plates as described in “Dendritic-cell cultures.” Culture supernatants of activated DCs were collected after 16 hours. Supernatants of cultures containing the parental L929 cells and sorted DCs were used as control to measure the cytokine secretion of immature DCs. (A-C) Mean values and SD of cytokine concentrations measured in the supernatant of nonactivated immature (IDC; □) and activated mature (MDC; ⊡) moDCs were calculated from data obtained in 2 independent experiments by the CBA assay (A-B) or with the cells of 7 individuals by ELISA (C). *P < .05; **P < .001. (D-E) Mean values and SD of cytokine concentrations measured by the CBA assay in the supernatants of CD1a− (□) and CD1a+ (▪) in moDC cultures derived from 7 individuals. (F) Comparison of intracellular IL-12p70 levels measured in CD1a+ (solid line) and CD1a− (thin line) in a typical experiment of 3 by flow cytometry. Dashed lines show fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with isotype-matched control antibody. (G) Mean and SD of biologically active TGF-β1 concentrations were calculated from data measured by ELISA in the acid-treated culture supernatants of 7 individuals. Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs were activated by soluble or cell-bound CD40L and used for activating allogeneic lymphocytes. Typical experiments of 3 are documented. (H) Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ DCs were seeded to flat-bottom 96-well plates at various numbers started at 5 × 104 cell/well, stimulated with 5 μg/mL soluble CD40L, and cocultured with 5 × 105/well allogeneic lymphocytes for 5 days. T-lymphocyte proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation added for the last 16 hours of the culture. (I) In a similar assay, IFN-γ concentrations were measured in cell-culture supernatants taken at day 3 of cocultures. (J) CD1a+ and CD1a− moDCs were sorted, plated to 24-well plates, and activated by CD40L-expressing L929 cells for 24 hours. Activated moDCs were cocultured with allogeneic lymphocytes at 10:1 lymphocyte/DC ratios, and secreted IFN-γ was measured in the supernatant at day 3 by ELISA. (K) Cytokine secretion of primed T lymphocytes was also tested in a restimulation assay on day 14, when resting cells were collected, counted, and plated to anti-CD3–coated 96-well plates. In this experiment, IFN-γ secretion was measured 24 hours after anti-CD3 restimulation. (L) The same supernatants were subjected to IL-10 measurements by ELISA. Error bars represent SD of 3H-thymidine incorporation in triplicate cell cultures (H) or SD of cytokine concentration in triplicate samples (G, I-L).

Cytokine secretion of CD40L-activated CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and cocultured activated allogeneic lymphocytes. Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ immature DCs (2 × 105) were cultured on a monolayer of CD40L (CD40L)–expressing L929 fibroblasts (0.4 × 105) in 24-well plates as described in “Dendritic-cell cultures.” Culture supernatants of activated DCs were collected after 16 hours. Supernatants of cultures containing the parental L929 cells and sorted DCs were used as control to measure the cytokine secretion of immature DCs. (A-C) Mean values and SD of cytokine concentrations measured in the supernatant of nonactivated immature (IDC; □) and activated mature (MDC; ⊡) moDCs were calculated from data obtained in 2 independent experiments by the CBA assay (A-B) or with the cells of 7 individuals by ELISA (C). *P < .05; **P < .001. (D-E) Mean values and SD of cytokine concentrations measured by the CBA assay in the supernatants of CD1a− (□) and CD1a+ (▪) in moDC cultures derived from 7 individuals. (F) Comparison of intracellular IL-12p70 levels measured in CD1a+ (solid line) and CD1a− (thin line) in a typical experiment of 3 by flow cytometry. Dashed lines show fluorescence intensity of cells incubated with isotype-matched control antibody. (G) Mean and SD of biologically active TGF-β1 concentrations were calculated from data measured by ELISA in the acid-treated culture supernatants of 7 individuals. Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs were activated by soluble or cell-bound CD40L and used for activating allogeneic lymphocytes. Typical experiments of 3 are documented. (H) Sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ DCs were seeded to flat-bottom 96-well plates at various numbers started at 5 × 104 cell/well, stimulated with 5 μg/mL soluble CD40L, and cocultured with 5 × 105/well allogeneic lymphocytes for 5 days. T-lymphocyte proliferation was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation added for the last 16 hours of the culture. (I) In a similar assay, IFN-γ concentrations were measured in cell-culture supernatants taken at day 3 of cocultures. (J) CD1a+ and CD1a− moDCs were sorted, plated to 24-well plates, and activated by CD40L-expressing L929 cells for 24 hours. Activated moDCs were cocultured with allogeneic lymphocytes at 10:1 lymphocyte/DC ratios, and secreted IFN-γ was measured in the supernatant at day 3 by ELISA. (K) Cytokine secretion of primed T lymphocytes was also tested in a restimulation assay on day 14, when resting cells were collected, counted, and plated to anti-CD3–coated 96-well plates. In this experiment, IFN-γ secretion was measured 24 hours after anti-CD3 restimulation. (L) The same supernatants were subjected to IL-10 measurements by ELISA. Error bars represent SD of 3H-thymidine incorporation in triplicate cell cultures (H) or SD of cytokine concentration in triplicate samples (G, I-L).

The distinct combination of cytokines and chemokines, secreted by the 2 moDC subpopulations, may modulate the outcome of T-lymphocyte responses. To this end we compared the T-lymphocyte–activating potential of CD1a− and CD1a+ moDC subsets in mixed-lymphocyte cultures. The potential of isolated CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs to induce allogeneic T-lymphocyte activation was compared by measuring proliferation and cytokine secretion. MoDCs activated by soluble CD40L induced T-lymphocyte proliferation in a DC number–dependent manner, but no difference could be shown between the activity of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells (Figure 4H). However, the concentration of IFN-γ measured on day 3 in the supernatant of the DC-lymphocyte cocultures was higher when T lymphocytes were activated by CD1a+ moDCs compared with CD1a− moDCs (Figure 4I). Next we preactivated the sorted CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs by CD40L-transfected L293 fibroblasts, cocultured them with allogeneic lymphocytes for 3 days, and measured the concentration of secreted cytokines. As shown in Figure 4J, CD1a+ moDCs induced higher IFN-γ release than CD1a− cells. This difference was even more obvious after secondary anti-CD3 restimulation of resting primed T lymphocytes (Figure 4K). We also monitored the presence of other cytokines in the DC-lymphocyte cultures: IL-4 could not be detected and IL-13 was present at low levels (data not shown), but in the presence of CD1a− moDCs higher amounts of IL-10 were detected than in the cultures with CD1a+ moDCs (Figure 4L). These results indicate that the different cytokine patterns of CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs are translated to functionally different cytokine responses of T lymphocytes.

Factors influencing the differentiation of monocyte-derived CD1a− and CD1a+ dendritic cells

Individual differences observed in the ratio of in vitro–generated CD1a+ moDCs (Table 1) and the distinct functional activity of these DC subsets prompted us to assess the possible effect of culture medium and serum components on the differentiation of moDC subsets. The average percentage of CD1a+ cells in RPMI 1640 medium substituted with 10% FCS was similar (49.4% ± 18.8%; n = 28) to that measured in AIMV medium (44.4% ± 22.6%; n = 87); however, high standard deviations reflected individual differences (Table 1). We postulated an exogenous inhibitory effect that interferes with the differentiation of CD1a+ moDCs. When the isolated monocytes of an individual were differentiated in AIMV or RPMI in the presence of 10% FCS, 10% LPDS, or 10% AB serum, marked differences were detected in the proportion of CD1a+ cells (Figure 5A). The highest percentage of CD1a+ cells was detected in serum-free RPMI supplemented with 1% ITS or LPDS (Figure 5A-B). Interestingly, AB serum and FCS inhibited the differentiation of CD1a+ cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5C). When FCS or AB serum was added to LPDS at graded concentrations, the dose-dependent inhibitory effect could be reconstituted, indicating that both bovine and human sera contain inhibitory components for CD1a+ cell differentiation (Figure 5D). These results suggest that not only is the differentiation of CD1a+ moDCs inhibited but also that the differentiation of CD1a− moDCs could be potentiated by serum-derived factors that are not available in the absence of lipoproteins. This was directly demonstrated by the effect of exogenous very low–density lipoprotein (VLDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), oxLDL, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) on CD1a− and CD1a+ dichotomy (Figure 5E). The lipoprotein-mediated effect on CD1a expression was detected at both the intracellular and membrane levels (Figure 5F), suggesting transcriptional regulation.

Effect of culture conditions on the differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Monocytes of a given individual were differentiated to DCs under different conditions. The results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. (A-B) DCs were differentiated in various culture media as indicated: AIMV, or RPMI without or with 10% FCS, 10% LPDS, 10% AB serum, or 1% ITS. The percentage of CD1a+ cells was determined at day 5 of culture by flow cytometry. (C) DCs were cultured in RPMI medium substituted with graded concentration of LPDS (□), FCS (⊡), and AB serum (▪). RPMI without serum are represented as ▧. (D) DCs were differentiated in 10% LPDS (□) substituted with graded concentration of FCS (⊡) or AB serum (▪). (E) MoDCs were differentiated in RPMI+1% ITS in the presence of 40 μg/mL (▪) or 10 μg/mL (⊡) lipoproteins as indicated. Control cultures did not contain lipoproteins. (F) MoDCs were differentiated in different culture media as indicated, and the percentage of CD1a+ cells was measured in live (extracellular [ec] CD1a; □) and permeabilized cells (extra- and intracellular [ec + ic] CD1a; ⊡).

Effect of culture conditions on the differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Monocytes of a given individual were differentiated to DCs under different conditions. The results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. (A-B) DCs were differentiated in various culture media as indicated: AIMV, or RPMI without or with 10% FCS, 10% LPDS, 10% AB serum, or 1% ITS. The percentage of CD1a+ cells was determined at day 5 of culture by flow cytometry. (C) DCs were cultured in RPMI medium substituted with graded concentration of LPDS (□), FCS (⊡), and AB serum (▪). RPMI without serum are represented as ▧. (D) DCs were differentiated in 10% LPDS (□) substituted with graded concentration of FCS (⊡) or AB serum (▪). (E) MoDCs were differentiated in RPMI+1% ITS in the presence of 40 μg/mL (▪) or 10 μg/mL (⊡) lipoproteins as indicated. Control cultures did not contain lipoproteins. (F) MoDCs were differentiated in different culture media as indicated, and the percentage of CD1a+ cells was measured in live (extracellular [ec] CD1a; □) and permeabilized cells (extra- and intracellular [ec + ic] CD1a; ⊡).

As serum lipoproteins are able to bind and transport various lipids into DCs,32 and CD1a− moDCs were characterized by exceptionally high activity in engulfing modified lipids (Figure 3C-D), we hypothesized that lipoprotein-mediated lipid internalization may have a regulatory function in moDC differentiation and in the balance of CD1a− and CD1a+ moDC generation.

Differential expression and activation of PPARγ in CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells

Our previous results have shown the rapid up-regulation and activation of PPARγ in the course of cytokine-induced moDC differentiation.25 As the nuclear hormone receptor PPARγ can be activated by endogenous lipid agonists, we compared PPARγ expression and activity in CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs. Figure 6A-B shows that PPARγ expression is apparently restricted to CD1a− cells. Proportional to PPARγ expression, mRNA levels of fatty-acid–binding protein-4 (FABP4; Figure 6C), adipose differentiation-related protein (ADRP; Figure 6D), and apolipoprotein E (ApoE; Figure 6E), all identified as target genes of PPARγ, were also higher in CD1a− cells and indicated the transcriptional activity of PPARγ. These results show that the generation of CD1a− moDCs is associated with and might be regulated or maintained by PPARγ, whereas the generation of CD1a+ cells is inhibited. These results also pointed to a link between lipid metabolism of moDCs and their consecutive differentiation from CD1a− to CD1a+ cells.

Expression and activation of PPARγ in CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immature moDCs were sorted to CD1a− and CD1a+ fractions and then RNA was isolated from 2 × 106 cells. Gene expression was measured by real-time QRT-PCR. Results obtained from 6 independent sorted moDC sample pairs are documented. CD1a+ and CD1a− cells are shown as ▪ and □, respectively. (A) Relative expression of CD1a mRNA in sorted CD1a+ and CD1a− moDC fractions. (B) Relative expression of PPARγ in CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. (C-E) Expression of the PPARγ target genes FABP4, ADRP, and APOE in sorted CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. Error bars represent SD of triplicate samples.

Expression and activation of PPARγ in CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immature moDCs were sorted to CD1a− and CD1a+ fractions and then RNA was isolated from 2 × 106 cells. Gene expression was measured by real-time QRT-PCR. Results obtained from 6 independent sorted moDC sample pairs are documented. CD1a+ and CD1a− cells are shown as ▪ and □, respectively. (A) Relative expression of CD1a mRNA in sorted CD1a+ and CD1a− moDC fractions. (B) Relative expression of PPARγ in CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. (C-E) Expression of the PPARγ target genes FABP4, ADRP, and APOE in sorted CD1a+ and CD1a− cells. Error bars represent SD of triplicate samples.

Endogenous PPARγ agonists are generated from polyunsaturated fatty acids33 derived from modified LDL or acquired from exogenous sources.7 MoDCs expressed CD91 and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDL-R; data not shown), described as mediators of ApoE-assisted lipid uptake.32 As PPARγ-regulated ApoE production is also restricted to CD1a− moDCs, we suggest that ApoE-mediated loading of CD1a− moDCs by exogenous lipids could be involved in the regulation of PPARγ through the generation of endogenous agonists. The intracellular production of these putative compounds is supported by our finding showing that lysophosphatidyl acid (LPA), which has been identified as a trans-cellular PPARγ agonist,34 had no effect on CD1a− and CD1a+ ratios in our system (data not shown) but serum lipoprotein loading had a dose-dependent effect on DC-subset dichotomy.

High phagocytic activity and limited IL-12 production has been attributed to CD1a− moDCs generated in the presence of PPARγ ligands.25,35,36 Based on our results, this effect can also be due to skewing moDC differentiation to CD14lowCD1a−PPARγ+ cells characterized by low IL-12 secretion. To test this scenario, we differentiated moDCs with or without RSG, a synthetic agonist of PPARγ. CD1a− and CD1a+ cells generated in these cultures were sorted and activated by CD40L-transfected L293 fibroblasts, and IL-12p70 concentrations were measured in the supernatant of control and RSG-treated DC cultures (data not shown). In line with our present results, CD1a− cells, derived from both control and RSG-treated cells, secreted about 6 times less IL-12p70 than CD1a+ cells. Although RSG had some inhibitory effect on the cytokine secretion of both CD1a+ and CD1a− moDCs, the major effect of RSG could be attributed to promoting CD1a− moDC differentiation characterized by low IL-12p70 secretion.

In vivo occurrence of PPARγ−CD1a+ and PPARγ+CD1a− dendritic cells

Epidermal CD1a+ LCs represent a unique type of DCs characterized by the expression of the C-type lectin Langerin/DC205, a known inducer of intracellular Birbeck granules specific for LCs.37 Immature LCs reside in the epidermis and in mucosal surfaces,38 whereas antigen uptake induces emigration of these cells from the epidermis or epithelial surfaces to draining lymph nodes where they undergo a transformation to antigen-presenting cells that may tolerize or activate T lymphocytes. To demonstrate that CD1a−PPARγ+ and CD1a+PPARγ− cells do represent distinct DC subpopulations in human tissues as well, we stained sections of normal or reactive lymph nodes, tonsils, and lung biopsies of a patient with Langerhans-cell histiocytosis26 by means of double IF or peroxidase techniques for CD1a and PPARγ. At physiologic conditions, human lymph nodes do not exhibit CD1a+ DCs, except for trace numbers of LCs in the perifollicular and sinusoid areas of subcutaneous lymph nodes (data not shown). Figure 7B-C shows CD1a+ and PPARγ+ cells in reactive lymph nodes as nonoverlapping separate cell types. The DC-specific molecules DC-SIGN and S100 are expressed by both PPARγ− and PPARγ+ cells (Figure 7D-E).

In vivo localization of CD1a+ PPARγ− and CD1a+ PPARγ+ dendritic cells. Double IF or IP stainings for PPARγ-expressing cells in human reactive lymph nodes (A-E) and lung tissues with histiocytosis-X (F-J) that may coexpress DC markers with characteristic antigen-presenting cell morphologies. (A,F-G) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE)–stained sections used for immunolabeling. (B-C) Lymph node with increased number of CD1a+ DCs (green cytoplasmic fluorescence) but negative for PPARγ expression (red nuclear fluorescence), both located predominantly at the interfollicular compartments (compare the position of germinal center [GC] in panel A with the cells in panels B and C separately stained for green and red). (D-E) Lymph node normally harbors both DC-SIGN–positive (D) and S100-positive (E) cells with characteristic cytoplasmic projections (green) and both may coexpress PPARγ nucleoprotein (red, arrowheads) or not contain detectable amounts of PPARγ (arrow). Note that few DC-like PPARγ+ cells with characteristic S100+ cytoplasmic projections can be seen within the germinal centers (not shown). (F-G) HE of disseminated pulmonary Langerhans-cell histiocytosis showing nodular infiltrates along the alveolar spaces (F, asterisks) and the characteristic morphology of proliferating LCs with oval vesiculated nuclei among the reactive lymphocytes and few eosinophils (G). The detailed clinicopathology of this case was reported earlier.26 Double IF (H) and IP on serial sections with identical fields (I-J) demonstrate that LCs with characteristic CD1a positivity (arrows) do not express PPARγ, which confirms our in vitro data and indicates that a double-positive antigen-presenting cell phenotype in human tissues is unlikely. Few PPARγ+ cells, however, are found in such lesions, likely corresponding to inflammatory macrophages (arrowheads). Identical bronchioles are indicated by the letter b. IF-stained sections have DAPI and IP-stained sections have methyl-green nuclear counterstainings. Objectives used: × 4/0.1 NA (F); × 20/0.4 NA (A-B,I-J); × 40/0.65 NA (E,G,H); × 100/1.3 NA oil (C-D).

In vivo localization of CD1a+ PPARγ− and CD1a+ PPARγ+ dendritic cells. Double IF or IP stainings for PPARγ-expressing cells in human reactive lymph nodes (A-E) and lung tissues with histiocytosis-X (F-J) that may coexpress DC markers with characteristic antigen-presenting cell morphologies. (A,F-G) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE)–stained sections used for immunolabeling. (B-C) Lymph node with increased number of CD1a+ DCs (green cytoplasmic fluorescence) but negative for PPARγ expression (red nuclear fluorescence), both located predominantly at the interfollicular compartments (compare the position of germinal center [GC] in panel A with the cells in panels B and C separately stained for green and red). (D-E) Lymph node normally harbors both DC-SIGN–positive (D) and S100-positive (E) cells with characteristic cytoplasmic projections (green) and both may coexpress PPARγ nucleoprotein (red, arrowheads) or not contain detectable amounts of PPARγ (arrow). Note that few DC-like PPARγ+ cells with characteristic S100+ cytoplasmic projections can be seen within the germinal centers (not shown). (F-G) HE of disseminated pulmonary Langerhans-cell histiocytosis showing nodular infiltrates along the alveolar spaces (F, asterisks) and the characteristic morphology of proliferating LCs with oval vesiculated nuclei among the reactive lymphocytes and few eosinophils (G). The detailed clinicopathology of this case was reported earlier.26 Double IF (H) and IP on serial sections with identical fields (I-J) demonstrate that LCs with characteristic CD1a positivity (arrows) do not express PPARγ, which confirms our in vitro data and indicates that a double-positive antigen-presenting cell phenotype in human tissues is unlikely. Few PPARγ+ cells, however, are found in such lesions, likely corresponding to inflammatory macrophages (arrowheads). Identical bronchioles are indicated by the letter b. IF-stained sections have DAPI and IP-stained sections have methyl-green nuclear counterstainings. Objectives used: × 4/0.1 NA (F); × 20/0.4 NA (A-B,I-J); × 40/0.65 NA (E,G,H); × 100/1.3 NA oil (C-D).

Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a reactive tumorlike disease characterized by the proliferation and accumulation of CD1a+ LCs and macrophages with an aggressive growth pattern.39 Figure 7F-J shows the accumulation of CD1a+ cells in lung lesions of a child with Langerhans cell histiocytosis,26 whereas normal lung tissue contained scattered CD1a+ LCs exclusively restricted to the mucosal layers of the bronchiolar system and low numbers of PPARγ+ cells (data not shown). The membrane expression of CD1a and the nuclear staining of PPARγ specify distinct cell populations within the lung lesions (Figure 7H-J). These results altogether demonstrate that CD1a−PPARγ+ and CD1a+PPARγ− cells are detected under physiologic conditions in peripheral and lymphoid tissues and also that PPARγ is a powerful inhibitor of LC differentiation toward the inflammatory CD1a+ subset in vivo.

Discussion

Our results show that moDCs represent a heterogeneous population comprising CD14lowCD1a− and CD14−CD1a+ cells that correspond to consecutive differentiation stages. Inflammatory cytokines block the transition of CD1a− cells to CD1a+ DCs and imprint the CD1a− phenotype, resulting in the maturation of both subsets. Immature CD1a− moDCs possess high internalizing capacity, whereas mature CD1a+ cells stand out by their capability to secrete high amounts of IL-12p70 and CCL1. Serum lipoproteins skew moDC differentiation to the generation of CD1a− cells, whereas the development of CD1a+ cells is inhibited. CD1a− moDCs express PPARγ and ApoE whereas CD1a+ DCs do not. CD1a−PPARγ+ and CD1a+PPARγ− moDCs appear as distinct cell types in lymphoid organs and in the lung. CD1a expression in vivo and in vitro has been shown to associate with various microenvironmental effects, among them serum supplements, pathogens, cytokines, heparin, or tumor-derived factors, but the mechanisms that may regulate CD1a membrane expression have not been identified.40-42 Our results show for the first time a link between lipoproteins, PPARγ activation, and the differentiation and functional activity of CD1− and CD1a+ DCs.

Previous studies revealed high variation in the secretion of inflammatory cytokines of human moDCs activated by LPS.43 We obtained similar results with moDCs activated by CD40L and we found substantial differences in the cytokine and chemokine secretion pattern of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells obtained from the same in vitro culture. CD1a+ moDCs produced significantly higher levels of IL-12p70 and CCL1 and less IL-10 than their CD1a− counterparts. IL-12p70 and IL-10 play opposing roles in polarizing antigen-specific T-lymphocyte responses, whereas CCL1 recruits CCR8+ LCs and T lymphocytes in synergy with the homeostatic chemokine CXCL12.44,45 Thus the different combination of cytokines and chemokines, secreted by the 2 moDC subpopulations coexisting at various ratios in different individuals, may modulate the recruitment of distinct cell populations to the site of antigen-specific activation and influence the outcome of the immune response by T-lymphocyte polarization.46 The capability of CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs to trigger differentially polarized T-lymphocyte responses was demonstrated in vitro by higher levels of IFN-γ and lower levels of IL-10 secretion in mixed-lymphocyte cultures. The different functional characteristics and the individually variable ratios of CD1a− and CD1a+ cells in the moDC population prompted us to search for factors that may drive the differentiation of the CD1a− and CD1a+ DC subsets. In monocytes, IL-4 has been shown to up-regulate 12/15-lipoxygenase, which generates endogenous PPARγ ligands and induces activation of the receptor.47,48 We have shown that PPARγ expression is induced within 2 to 3 hours during moDC differentiation, and the presence of RSG results in the down-regulation of CD1a gene and protein expression and up-regulation of the scavenger receptor CD36, a key fatty-acid transporter.25 Here we show that CD1a− cells efficiently internalize lipoproteins and modified LDL; stabilization of the CD1a− phenotype requires serum lipoproteins and is associated with PPARγ expression and activation. In contrary, depletion of lipoproteins supports the differentiation of CD1a+ cells without PPARγ expression. Based on these results, we suggest that monocytes and differentiating DCs continuously internalize serum-born exogenous lipids with the assistance of serum lipoproteins,32 which leads to the generation of endogenous PPARγ agonists. Consequently, ligand-induced activation of PPARγ initiates a cascade of gene transcription that coordinates lipid metabolism as well as the regulation of lipid-presenting CD1a and CD1d gene and protein expression.25 Considering standard lipid concentrations in AIMV medium, the dependence of CD1a+/CD1a− ratios in moDCs may reflect individually different levels of endogenous PPARγ ligands of monocytes acquired in vivo. Thus the generation of endogenous PPARγ ligands may be a limiting factor for the generation of CD14lowCD1a− tissue DCs. This possibility is supported by our results, with moDCs generated in the presence of lipoproteins, and our preliminary data showing a strong correlation of CD1a+ moDC percentages, measured in the in vitro cultures of randomly selected blood donors, with body weight but not with other known parameters such as sex or age (data not shown). Exogenous lipid microparticles, oxLDL, or phospholipids internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis may serve as exogenous sources of PPARγ ligands,7,32,33 whereas PPARγ-induced expression of ApoE in CD1a− moDCs may support lipid uptake.

The in vivo existence of CD1a−PPARγ+DC-SIGN+ and CD1a+PPARγ−DC-SIGN+ DCs as distinct cell types in peripheral lymphoid tissues suggests the functional role of these DC subsets in vivo. These results also identify PPARγ as a possible in vivo inhibitor of CD1a expression, as in the lung both DC subsets are present but PPARγ expression is detected only in CD1a− DCs. We hypothesize that the level of endogenous PPARγ ligand is also able to modulate CD1a− and CD1a+ dichotomy in vivo. Below a critical level of endogenous ligands PPARγ is not activated, resulting in CD1a+ DCs with the potential to secrete biologically active IL-12p70 upon CD40-mediated signaling. In contrast to these cells, DCs that express activated PPARγ remain in a less mature, tolerogenic differentiation state with high internalizing capacity, migratory potential, and the preferential secretion of IL-10 upon CD40-mediated activation. It has been shown that PPARγ activation impairs the immunogenicity of human moDCs upon stimulation with various Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands by inhibiting the MAP kinase and NK-κB signaling pathways.49 Furthermore, PPARγ agonists were reported to increase the production of IL-10 by T lymphocytes.50 We suggest that CD1a− and CD1a+ moDCs respond to CD40 ligation with differently balanced cytokine/chemokine secretion due to their distinct differentiation stages specified by the expression and activation state of nuclear PPARγ and membrane CD1a.

MoDCs have emerged as promising adjuvants of cancer vaccines due to their potential to polarize CD4+ T lymphocytes to IFN-γ secretion and CD8+ T-cell activation through IL-1251 in various clinical settings.52-54 Our results suggest that PPARγ activation modulated by individually different levels of environmental lipids, including those released by tumor cells, would be able to modulate the generation of IL-12–secreting CD1a+ inflammatory and IL-10–producing CD1a− tolerogenic DCs and thus influence the outcome of antitumor immune responses and therapy. Thus the capability of circulating monocytes to generate CD1a+ cells may be considered an important marker for predicting the efficacy of moDC-based immunotherapies. Furthermore, monitoring characteristic CD1a−/CD1a+ moDC ratios in the context of serum-lipid parameters may uncover new aspects of the interplay of lipid homeostasis and immunity.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Istvan Kurucz and Dr Attila Bacsi for comments on the manuscript. The authors acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Aniko Gergely and Erzsebet Kovacs.

This work was supported by the Hungarian National Research Fund (OTKA T043420; E.R.) and by the National Office for Research and Technology (NKFP 00427/2004; E.R. and L.N.).

![Figure 5. Effect of culture conditions on the differentiation of CD1a− and CD1a+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Monocytes of a given individual were differentiated to DCs under different conditions. The results shown are representative of 4 independent experiments. (A-B) DCs were differentiated in various culture media as indicated: AIMV, or RPMI without or with 10% FCS, 10% LPDS, 10% AB serum, or 1% ITS. The percentage of CD1a+ cells was determined at day 5 of culture by flow cytometry. (C) DCs were cultured in RPMI medium substituted with graded concentration of LPDS (□), FCS (⊡), and AB serum (▪). RPMI without serum are represented as ▧. (D) DCs were differentiated in 10% LPDS (□) substituted with graded concentration of FCS (⊡) or AB serum (▪). (E) MoDCs were differentiated in RPMI+1% ITS in the presence of 40 μg/mL (▪) or 10 μg/mL (⊡) lipoproteins as indicated. Control cultures did not contain lipoproteins. (F) MoDCs were differentiated in different culture media as indicated, and the percentage of CD1a+ cells was measured in live (extracellular [ec] CD1a; □) and permeabilized cells (extra- and intracellular [ec + ic] CD1a; ⊡).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/2/10.1182_blood-2006-04-016840/4/m_zh80020706660005.jpeg?Expires=1767710481&Signature=WtaMlfpTKMnOxmP2XNSqEYB-12jcysYC6MYsjAkXB0NsOgJiQ7TUclYiwhxBvr0uaWrMtx5Wm8egO3B3q61rYhP0qUbnoVHi9dWbLsaCAQDJ8ayXyVwbWoHPib8ij2qUgfzQeZyntsGa1pImmZAhki8Kj4wmx5PbOSqLgS3mbuMqMGcn-ZqLzWzGJnwEVg-u2EPt5aega-TmqcCZrLNIKSDYCx4cg4zYA9FWwBTUdZzupUMSsJdsQyow6YFulAo7iIrwb7fwBB8v7jgWejscsrcC0RGe6CQGMypEgmN9akLfHmQ7CoFMCMvVa71aCWUDk0Qyi5EJL5QAxOblxllOZg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. In vivo localization of CD1a+ PPARγ− and CD1a+ PPARγ+ dendritic cells. Double IF or IP stainings for PPARγ-expressing cells in human reactive lymph nodes (A-E) and lung tissues with histiocytosis-X (F-J) that may coexpress DC markers with characteristic antigen-presenting cell morphologies. (A,F-G) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE)–stained sections used for immunolabeling. (B-C) Lymph node with increased number of CD1a+ DCs (green cytoplasmic fluorescence) but negative for PPARγ expression (red nuclear fluorescence), both located predominantly at the interfollicular compartments (compare the position of germinal center [GC] in panel A with the cells in panels B and C separately stained for green and red). (D-E) Lymph node normally harbors both DC-SIGN–positive (D) and S100-positive (E) cells with characteristic cytoplasmic projections (green) and both may coexpress PPARγ nucleoprotein (red, arrowheads) or not contain detectable amounts of PPARγ (arrow). Note that few DC-like PPARγ+ cells with characteristic S100+ cytoplasmic projections can be seen within the germinal centers (not shown). (F-G) HE of disseminated pulmonary Langerhans-cell histiocytosis showing nodular infiltrates along the alveolar spaces (F, asterisks) and the characteristic morphology of proliferating LCs with oval vesiculated nuclei among the reactive lymphocytes and few eosinophils (G). The detailed clinicopathology of this case was reported earlier.26 Double IF (H) and IP on serial sections with identical fields (I-J) demonstrate that LCs with characteristic CD1a positivity (arrows) do not express PPARγ, which confirms our in vitro data and indicates that a double-positive antigen-presenting cell phenotype in human tissues is unlikely. Few PPARγ+ cells, however, are found in such lesions, likely corresponding to inflammatory macrophages (arrowheads). Identical bronchioles are indicated by the letter b. IF-stained sections have DAPI and IP-stained sections have methyl-green nuclear counterstainings. Objectives used: × 4/0.1 NA (F); × 20/0.4 NA (A-B,I-J); × 40/0.65 NA (E,G,H); × 100/1.3 NA oil (C-D).](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/2/10.1182_blood-2006-04-016840/4/m_zh80020706660007.jpeg?Expires=1767710481&Signature=3M2NqQae0h1L1QHTAeG4W-gSq4Ts6HOgHPk76aHdrUfcsRSh~ftx7ZFwIo7AsXArkN~CJ2gv6gT2ghHWvhV2Y1JEPcWNLymlA8jdivuUrHgoNb4h7UyUwPnYXdFavHY-9TpAX8fxIHYAVmcA2VJ83vXLYD2CZRVhCF6zWRjX4a-dgiMk4R0JUR1SVvA7J-N54Gyo~9VyID~-kNMX5~~hyHrsBXij9YuMKePhxw9qzxUFIMTF1hOmKlSEP2MSgOJfZVtHtUo0PDTgVMBBBYx4aztvBFH36cxhESbD-3WGIJ2-vtzHJEGzR7TMuig4h2TTqDVkWAvf7oFFwQVLHICvoA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal