Abstract

Acute graft-versus-host disease (aGVHD) impairs thymus-dependent T-cell regeneration in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow transplants through yet to be defined mechanisms. Here, we demonstrate in mice that MHC-mismatched donor T cells home into the thymus of unconditioned recipients. There, activated donor T cells secrete IFN-γ, which in turn stimulates the programmed cell death of thymic epithelial cells (TECs). Because TECs themselves are competent and sufficient to prime naive allospecific T cells and to elicit their effector function, the elimination of host-type professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) does not prevent donor T-cell activation and TEC apoptosis, thus precluding normal thymopoiesis in transplant recipients. Hence, strategies that protect TECs may be necessary to improve immune reconstitution following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.

Introduction

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (alloBMT) is the preferred therapeutic option for a number of life-threatening disorders, including those of the lymphohematopoietic system.1,2 A favorable outcome of alloBMT depends, in turn, on the comprehensive reconstitution of the host's immune system. Whereas recovery of peripheral T cells occurs in transplant recipients via thymus-dependent and -independent mechanisms,3,4 the regeneration of phenotypically naive T cells with a broad TCR repertoire relies on the de novo generation of T cells in the thymus.3,5–11 However, alloBMT is associated with toxicities, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which limit thymus-dependent T-cell generation. Acute GVHD (aGVHD) is induced by donor T cells interacting with specific cells of the recipient.12,13 In murine models and in human BMT, professional (p) antigen-presenting cells (pAPCs) of the host are believed to be critical in initiating acute graft-versus-host responses.14–19 Activated donor T cells trigger an inflammatory cascade that includes multiple cellular and cytokine effectors that are responsible for cell injury in a restricted set of target tissues.12,20,21 In this respect, aGVHD also affects thymic structure and function.22–27 The resultant deficiency in the peripheral T-cell pool contributes to a patient's risk for life-threatening infections.10,27–29

Thymic T-cell development relies on signals provided by a functionally competent 3-dimensional network of stromal cells.30 This compartment consists of different cell types that collectively enable the attraction, survival, expansion, migration, and differentiation of T-cell precursors. The thymic epithelial cells (TECs) constitute the most abundant cell type of the stroma and can be differentiated into phenotypically and functionally separate subpopulations.30–34 The absence of a regularly structured and composed thymic microenvironment precludes regular thymocyte development.35 We have previously established in a radiation-independent transplantation model that aGVHD perturbs the architectural organization and composition of the thymic microenvironment.25 These alterations were characterized by a decrease and occasional loss of distinct TEC subpopulations. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which aGVHD causes these deficits have remained unknown. Loss of integrity of the thymic microenvironment following alloBMT was firmly associated with an invasion of donor T cells into the recipient's thymus, a reduction in thymopoietic capacity and thymic output, and diminished peripheral T-cell reconstitution.22,23,25,26

Here we report that TECs undergo programmed cell death following transfer of T cells into unconditioned, MHC-disparate murine recipients. In vitro data indicated a direct and causative link between donor T-cell activation to host alloantigens, IFN-γ secretion, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT-1) activation in TECs, and caspase-dependent TEC apoptosis. Importantly, donor T-cell activation in vivo by host pAPCs was not required for induction of thymic epithelial injury because TECs themselves displayed a cell autonomous capacity to prime naive allogeneic T cells and to elicit IFN-γ secretion. From these data we infer that the depletion of host-derived hematopoietic pAPCs as part of pretransplant conditioning in clinical BMT will not prevent the activation of alloreactive donor T cells. Hence, strategies directed at a protection of TECs from transplantation-related injuries may be necessary to improve T-cell reconstitution.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female C57BL/6 (B6, H-2b, CD45.2+), Balb/c (H-2d), (C57BL/6 x DBA/2)F1 (BDF1, H-2bd, CD45.2+), B6.SJL-PtprcaPep3b/BoyJ (B6.CD45.1; H-2b, CD45.1+), B6.Cg/Ntac-Foxn1nuN9 (B6.nu/nu), CanN.Cg-Foxn1nu/Crl (Balb/c.nu/nu), 129S6/SvEvTac-Stattm1Rds (129.STAT1−/−; H-2b), and 129S6/SvEvTac (129Sv; H-2b) were obtained from Biological Research Laboratories (Füllinsdorf, Switzerland), Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), Charles River (Lyon, France), and Taconic Europe (Ry, Denmark), respectively. IFN-γ−/− mice (GKO) that had been bred on a Balb/c background were kindly provided by Dr U. Eriksson (University Hospital, Basel, Switzerland). Animals between 6 and 10 weeks of age were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions and in accordance with federal regulations.

Flow cytometry

For flow cytometry, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against CD3 (clone KT3), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (53-6.7), TCRβ (H57-592), CD44 (IM7), CD25 (PC61), CD45.1 (Ly5.1; A20), B220 (RA3-6B2), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), CD62L (MEL-14), CD69 (H1.2F3), H-2Kb (AF6-88.5), H-2Kd (SF1-1.1), CD45 (30-F11), and I-Ab (AF6-120.1) were obtained from BD Biosciences PharMingen (San Diego, CA) or eBioscience (San Diego, CA). The anti–IFN-γ mAb clone XMG1.2 (eBioscience) was used to detect intracellular IFN-γ production by T cells, some of which had been cultured for 4 hours with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA; 5 ng/mL), ionomycin (500 ng/mL), and brefeldin A (500 ng/mL). To detect apoptosis, cells were labeled with annexin V-allophycocyanin (BD Biosciences, Allschwil, Switzerland) and propidium iodide (PI). Labeled cells were analyzed on a FACScalibur dual laser (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). For analysis of procaspase-12, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and incubated with polyclonal antibody ab8118 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

TEC lines

The cortical thymic epithelial cell lines TEC1-2 and TEC1C9 and the medullary lines TEC2-3 and TEC3-10 (Figure S1; available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) were obtained from B6 mice (kindly provided by Dr M. Kasai, Tokyo, Japan).36,37 Cells were plated at 105 cells/well and recombinant mouse (rm)IFN-γ (R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom) was added. The pan-caspase inhibitor quinolyl-valyl-O-methylaspartyl-[5,6-difluorophenoxy]-methyl ketone (Q-VD-OPh; R&D Systems) was included in some cultures (5 μM). Floating and adherent cells were collected for analysis after 72 hours of culture. For mixed epithelial-lymphocyte reactions (MELRs), 2 × 106 T cells from naive or primed B6 (H-2b) and Balb/c (H-2d) mice, respectively, were added to untreated TEC1-2 (H-2b) plated the day before. Priming of responder cells prior to MELRs had been achieved during a 6-day primary mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) with allogenic splenic stimulators. After 72 hours of MELRs, supernatants were collected for IFN-γ determination by sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using mAbs from PharMingen, and cells were prepared for flow cytometric analysis. Lymphocytes were excluded based on their expression of CD45. The anti–IFN-γ mAb clone XMG1.2 was used to block IFN-γ activity in culture.

Adult TEC cultures

Pure CD45−I-Ab int+high thymic epithelial cells (< 99.9%) were isolated from adult thymic stromal cell preparations of naive B6 mice using a FACSAria cell sorter (Becton Dickinson; Figure S1). Reaggregate cultures were prepared according to a published protocol.38 Here, intact thymic aggregates formed from cell mixtures within 12 to 18 hours. IFN-γ was added to the final concentrations indicated. Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry after 72 hours of culture as described (see “Flow cytometry”). To test the T-cell priming potential of adult TECs, purified lymph node T cells (< 97% purity) were labeled with carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a concentration of 2.5 μM. Subsequently, T cells were reaggregated with the CD45−I-Ab int+high primary adult TECs at a 4:1 ratio and the cell mixture was placed on Nucleopore filters. T cells were harvested after 96 hours, cultured for 4 hours in the presence of PMA, ionomycin, and brefeldin A (see “Flow cytometry”), and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Reaggregation cultures and grafting of fetal TECs

Thymic lobes from fetal mice were cultured with 2-deoxyguanosine for 6 days, as described,38 and were then depleted from CD45+ cells. The resultant preparations consisted of 80% TECs and were devoid of hematopoietic cells as determined by flow cytometry (> 99.9% CD45−; Figure S1). Reaggregate cultures were subsequently prepared38 and after 24 hours in culture, the solidified reaggregate was grafted under the kidney capsule of athymic recipient mice. Two different models were studied: the grafting of BDF1 fetal TECs (E13) into B6.nu/nu mice (H-2b), and the grafting of strain 129 STAT-1−/− or STAT-1+/+ fetal TECs (E14, H-2b) into Balb/c.nu/nu recipients (H-2d). Engrafted mice received 4 to 5 weeks later by intravenous injection in the first model 15 × 106 B6.CD45.1 T cells or 8 × 106 Balb/c T cells in the second. Heterotopic thymi were analyzed after another 3 weeks.

GVHD induction

aGVHD was induced in nonirradiated BDF1 (H-2bd) mice, as described.22 Briefly, recipients were infused intravenously with 15 × 106 B6.CD45.1 (H-2b) splenic T cells and were designated as b→bd. As controls, 15 × 106 syngeneic BDF1 splenic T-cells were infused into cohorts (bd→bd).

BM chimeras

To produce [b⇒bd] BM chimeras, naive BDF1 mice were depleted of natural killer (NK) cells using PK136 (400 μg/mouse intraperitoneally; day −1). On day 0, mice were lethally irradiated with 11 Gy (137Cs source at 0.91 Gy/min) and subsequently given transplants with T cell-depleted BM cells (1 × 107) from naive B6 donors. At 3 to 4 months after transplantation, host and donor-type pAPCs in [b⇒bd] chimeras were identified in primary and secondary lymphoid organs and in the skin by expression of CD11b and CD11c, and H-2Kb and H-2Kd, respectively (Figure S2). Mice with donor dendritic cell (DC) engraftment of more than 98% in lymphoid tissues were subsequently infused intravenously with 15 × 106 splenic T cells from B6.CD45.1 mice and were designated 45.1+→[b⇒bd]. To eliminate residual radioresistant host DCs in the skin,19,39 some [b⇒bd] chimeras were exposed to UV light 4 weeks prior to infusion of T cells (Figure S2).

Immunoblot analysis

For detection of STAT-1 phosphorylation and caspase-12 cleavage, cell lysates were immunoblotted using rabbit anti–phospho-STAT1 (Tyr701) polyclonal IgG (∼92 kDa; no. 07-307; Millipore Upstate, Lucerne, Switzerland) and ab1881 (Abcam), respectively.

Quantitative PCR and DNA microarray analysis

Caspase-12 mRNA expression was measured by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in CD45−I-Ab int+high TECs, as described in the Supplemental Materials. To determine gene expression profiles in TECs, biotin-labeled and fragmented cRNA from sorted CD45−I-Ab+MTS24−TECs was hybridized to DNA microarrays (Affymetrix Mouse Expression Set MOE430A) as detailed in Table S1.

Immunofluorescence confocal microscopy

For analysis of medullary and cortical populations of TECs,31–33 frozen thymic sections (6 μm) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS and stained with mAb to cytokeratin (K)18 (Ks18.04, Progene, Heidelberg, Germany), polyclonal antibody to K5 (Covance, Princeton, NJ), biotinylated UEA1 lectin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and mAb against MTS-10 (BD Biosciences). Antibodies and lectin were applied in different combinations as detailed in a previous report25 and also in the Supplemental Materials. In additional experiments, orthotopic or ectopic thymi were analyzed using mAbs against CD31 (clone MTS12, provided by Richard Boyd, Melbourne, Australia), ERTR7 (provided by Willem van Ewijk, Utrecht, The Netherlands), and ab8118. Alexa-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated secondary reagents were obtained from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR). The level of in situ apoptosis in mouse thymi was evaluated by localizing internucleosomal DNA degradation on stained tissue sections, using the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Zug, Switzerland), which is a modification of the terminal deoxynucleotide transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay. All images were captured on a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope system (Carl-Zeiss, Feldbach, Switzerland). Isotype controls were used in all experiments. Overlays of blue (Cy5), red (Alexa555), and green (TUNEL or Alexa488) stainings were colored by computer-assisted management of confocal microscopy data generated with Zeiss LSM 510 software version 3.2.

Statistical analysis

Values are mean ± SD. For 2-group comparisons the nonparametric unpaired U test was used, whereas for multiple group comparisons, analysis of variance was used (StatView, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The overall statistical significance level was set to 5%.

Results

TECs undergo apoptosis during aGVHD

We previously demonstrated that aGVHD in the nonirradiated B6→BDF1 model (H-2b→H-2bd; b→bd) caused severe morphologic alterations in the thymic stromal microenvironment25 (Figure S3). In particular, the cytokeratin (K)18+ TEC subpopulations25,32,33 were largely lost in the presence of aGVHD, identifying these cells as targets. To determine whether TECs were lost by programmed cell death, we used the same haploidentical transplantation model as described. Two weeks after aGVHD induction, a large fraction of thymic cells displayed a hallmark of apoptosis as revealed by positivity for TUNEL (Figure 1A). In parallel, thymi from mice with aGVHD presented a collapsed stromal structure as demonstrated by dense TEC areas (Figures 1B and S3, and Rossi et al25 ). The population most affected by apoptosis were immature host-type (ie, CD4+CD8+ double-positive [DP]) thymocytes (Krenger et al23 and data not shown) but a substantial number of K18+ TECs were also subjected to programmed cell death (Figure 1C). Apoptotic TECs were typically located in areas displaying elevated epithelial density and could be detected adjacent to dying thymocytes (Figure 1D). In contrast, frequencies of apoptotic cells and thymic structure were normal in mice infused with syngeneic T cells (bd→bd; Figure 1E-H). Hence, K18+ TECs are subject to apoptosis following infusion of alloreactive T cells into nonablated, MHC-disparate hosts.

Thymic epithelial cells undergo apoptosis during aGVHD. Thymic sections from unconditioned BDF1 mice were analyzed 2 weeks after infusion of T cells from allogeneic B6.CD45.1 mice (b→bd, A-D) or syngeneic BDF1 mice (bd→bd, E-H). TUNEL+ cells among total thymic cells are shown in green (40×/0.75 numerical aperture [NA] objective). For TEC analysis, thymic sections were stained for the intracellular cytokeratin K1825 (shown in red). aGVHD in this nonirradiated model results in severe morphologic alterations in the thymic stromal microenvironment, with a loss in regular organization among K5−K18+, K5+K18− and K5+K18+ TECs (Figure S3 and Rossi et al25 ). The colocalization of TUNEL and K18 denotes apoptotic TECs (yellow, arrows in insets panels C and D; original magnification × 160 for panels D and H) whose detection depends also on the orientation of the epithelial cell. Areas of elevated epithelial density and TUNEL+ TECs were not seen in thymi of mice receiving syngeneic transplants. The relatively low frequency of apoptotic TECs was consistent with the established efficiency of the thymic microenvironment to remove apoptotic-cell debris and also with the high turnover of epithelial cells in situ.40,41 Four individual experiments were performed, with 2 to 4 animals per group and experiment. Because these experiments yielded comparable results, a representative photomicrograph is shown for each group.

Thymic epithelial cells undergo apoptosis during aGVHD. Thymic sections from unconditioned BDF1 mice were analyzed 2 weeks after infusion of T cells from allogeneic B6.CD45.1 mice (b→bd, A-D) or syngeneic BDF1 mice (bd→bd, E-H). TUNEL+ cells among total thymic cells are shown in green (40×/0.75 numerical aperture [NA] objective). For TEC analysis, thymic sections were stained for the intracellular cytokeratin K1825 (shown in red). aGVHD in this nonirradiated model results in severe morphologic alterations in the thymic stromal microenvironment, with a loss in regular organization among K5−K18+, K5+K18− and K5+K18+ TECs (Figure S3 and Rossi et al25 ). The colocalization of TUNEL and K18 denotes apoptotic TECs (yellow, arrows in insets panels C and D; original magnification × 160 for panels D and H) whose detection depends also on the orientation of the epithelial cell. Areas of elevated epithelial density and TUNEL+ TECs were not seen in thymi of mice receiving syngeneic transplants. The relatively low frequency of apoptotic TECs was consistent with the established efficiency of the thymic microenvironment to remove apoptotic-cell debris and also with the high turnover of epithelial cells in situ.40,41 Four individual experiments were performed, with 2 to 4 animals per group and experiment. Because these experiments yielded comparable results, a representative photomicrograph is shown for each group.

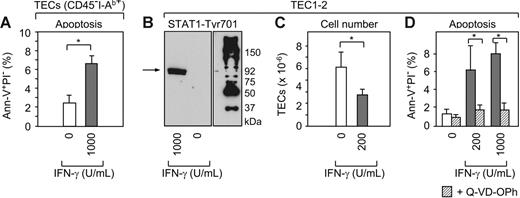

IFN-γ activates STAT-1 and induces apoptosis of TECs

Following B6→BDF1 transplantation, donor-derived mature T cells invade the host thymus where they expand and secrete IFN-γ (CD8+ > CD4+ donor T cells).22 A plausible role for IFN-γ in the pathogenesis of TEC apoptosis was initially suggested by global gene expression analyses where numerous IFN-γ–inducible genes were found to be enhanced in TECs during aGVHD (Figure S4 and Table S1). Consistent with a role for IFN-γ, the expression levels of STAT-1 were up-regulated in TECs by 6-fold. Indeed, activation of STAT-1 in response to IFN-γ had previously been implicated in apoptosis.42,43 To identify a definitive role for IFN-γ in TEC apoptosis, we tested the in vitro response of primary CD45−I-Ab+ TECs to this cytokine. When grown in culture for 3 days in the presence of 103 U/mL rmIFN-γ, the frequency of apoptotic TECs (ie, annexin-V+/PI−) increased when compared to cultures not exposed to IFN-γ (Figure 2A). Because the culture of primary TECs is associated with high spontaneous apoptotic death and the rapid loss of TEC-specific features in surviving cells (data not shown and Anderson et al44 ), we chose to validate the IFN-γ effect using different TEC lines.36,37 Exposure of cortical TEC1-2 cells to rmIFN-γ led to phosphorylation of STAT-1 at the Tyr701 residue, demonstrating activation in response to IFN-γ (Figure 2B). In parallel, IFN-γ treatment reduced the number of TEC1-2 cells by half within 3 days (Figure 2C), whereas the frequency of apoptotic cells increased when compared to control cultures (Figure 2D). Identical results were found for cortical TEC1C9 cells and the medullary lines TEC2-3 and TEC3-10 (Figure S1). This IFN-γ–induced TEC-cell death was effected via the activation of procaspases since the addition of the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh reduced apoptosis to background levels (Figure 2D). Consistently, preliminary data indicated the activation of caspase-12 in TEC1-2 in response to IFN-γ, and also its enhanced expression in TECs during aGVHD, suggesting a putative role for this caspase in TEC apoptosis (Figure S4).

IFN-γ activates STAT-1 in TECs and induces caspase-mediated programmed cell death. (A) Freshly isolated CD45−I-Ab int+high adult TECs (Figure S1) were cultured without (□) or with rmIFN-γ (⊡) at the indicated concentration (U/mL). Apoptotic TECs (ie, Ann-V+PI−) were quantified after 72 hours of culture. A total of 4 experiments were performed. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05. (B) TEC1-2 cells37 were cultured for 72 hours with rmIFN-γ and Tyr701 phosphorylated STAT-1 was detected by immunoblot analysis (∼92 kDa). (C-D) TEC1-2 were cultured with rmIFN-γ as indicated without or with (▨) the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh. Total cell numbers and apoptotic TEC1-2 were calculated from pooled data from 4 experiments. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05.

IFN-γ activates STAT-1 in TECs and induces caspase-mediated programmed cell death. (A) Freshly isolated CD45−I-Ab int+high adult TECs (Figure S1) were cultured without (□) or with rmIFN-γ (⊡) at the indicated concentration (U/mL). Apoptotic TECs (ie, Ann-V+PI−) were quantified after 72 hours of culture. A total of 4 experiments were performed. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05. (B) TEC1-2 cells37 were cultured for 72 hours with rmIFN-γ and Tyr701 phosphorylated STAT-1 was detected by immunoblot analysis (∼92 kDa). (C-D) TEC1-2 were cultured with rmIFN-γ as indicated without or with (▨) the pan-caspase inhibitor Q-VD-OPh. Total cell numbers and apoptotic TEC1-2 were calculated from pooled data from 4 experiments. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05.

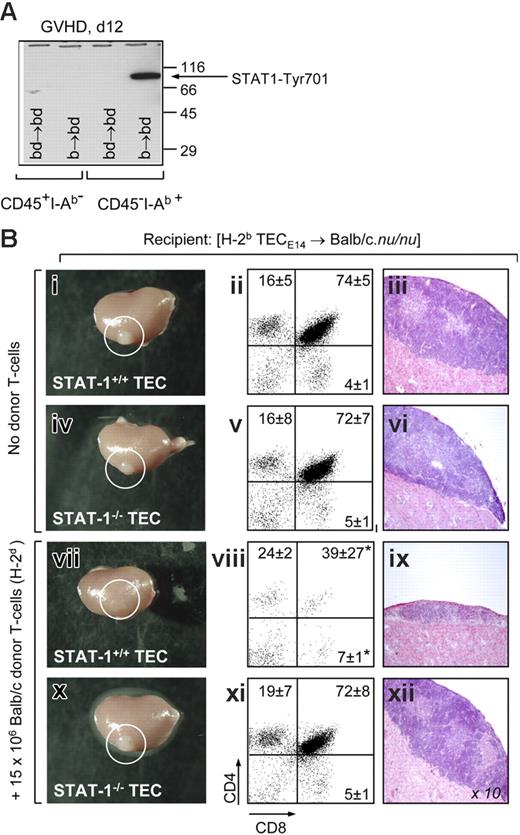

Abrogation of STAT-1 signaling in TECs prevents epithelial-cell loss in vivo

Because TECs displayed also in vivo activation of STAT-1 in the presence of aGVHD (Figure 3A), we next investigated whether IFN-γ signaling was required for TEC apoptosis. We had already demonstrated that highly purified fetal BDF1 TECs (H-2bd) grafted into immunodeficient B6.nu/nu mice (H-2b) could be recognized and destroyed by infused allogeneic (H-2b) T cells (Figure S1). We next grafted STAT-1+/+ and STAT-1−/− TECs from strain 129 mice (H-2b) under the kidney capsules of Balb/c.nu/nu mice (H-2d). After 5 weeks, the grafted epithelia were able to support normal ectopic T lymphopoiesis, resulting in a morphologically normal thymus (Figure 3Bi-vi). The subsequent intravenous transfer of 15 × 106 mature Balb/c T-cells (H-2d) caused within 3 weeks a considerable reduction in the sizes of the allogeneic STAT-1+/+ thymi (Figure 3Bvii). Identical to the situation in B6.nu/nu mice (Figure S1), these tissues displayed severe morphologic changes (Figure 3ix), including the collapse of the TEC meshwork (data not shown). Stromal changes were associated with a deficit in ectopic T-cell maturation that was characterized by aberrant frequencies of DP cells and CD8 single-positive (SP) mature thymocytes (Figure 3Bviii). These aberrant frequencies were indistinguishable from those typically present in orthotopic thymic tissue during aGVHD.22 In contrast, allogeneic STAT-1−/− thymic grafts preserved a normal phenotype and supported regular T-cell development despite the infusion of alloreactive T cells (Figure 3Bx-xii). Collectively, these data indicated a requirement for IFN-γ–mediated signaling for in vivo TEC damage by alloreactive T cells.

Abrogation of STAT-1 signaling in TECs prevents injury in vivo. (A) Phosphorylation of STAT-1 at residue 701 was detected by Western blot in purified primary adult CD45−I-Ab+ TECs and CD45+I-Ab− thymocytes from mice with aGVHD (b→bd, day 12). (B) Analysis of T cell-deficient Balb/c.nu/nu mice (H-2d) carrying a heterotopic thymus derived from E14 fetal STAT1+/+ and STAT-1−/− TECs (strain 129; H-2b), respectively (Figure S1). Panels i-vi depict gross anatomy (left), flow cytometric analysis (middle), and histology (right) of ectopic thymi located under the kidney capsule (circles) of recipients not further treated with allogeneic donor T cells. One representative mouse per group is shown. Images in panels iii, vi, ix, and xii were visualized using a Nikon E600 microscope (Nikon, Zurich, Switzerland) equipped with a 10×/0.30 NA objective. Images were acquired using a Nikon DXM 1200F camera and Nikon ACT-1 software version 2.62. Panels vii-xii depict the analyses of ectopic thymi from mice that have received 15 × 106 Balb/c T cells 3 weeks earlier. For analysis of ectopic T-cell development, relative numbers (in percent) of immature CD4+CD8+ and SP mature thymocytes, respectively, are shown. A total of 3 mice were analyzed for each transplantation group. The experiment was performed twice, with identical results; *P < .05 versus mice receiving no T cells.

Abrogation of STAT-1 signaling in TECs prevents injury in vivo. (A) Phosphorylation of STAT-1 at residue 701 was detected by Western blot in purified primary adult CD45−I-Ab+ TECs and CD45+I-Ab− thymocytes from mice with aGVHD (b→bd, day 12). (B) Analysis of T cell-deficient Balb/c.nu/nu mice (H-2d) carrying a heterotopic thymus derived from E14 fetal STAT1+/+ and STAT-1−/− TECs (strain 129; H-2b), respectively (Figure S1). Panels i-vi depict gross anatomy (left), flow cytometric analysis (middle), and histology (right) of ectopic thymi located under the kidney capsule (circles) of recipients not further treated with allogeneic donor T cells. One representative mouse per group is shown. Images in panels iii, vi, ix, and xii were visualized using a Nikon E600 microscope (Nikon, Zurich, Switzerland) equipped with a 10×/0.30 NA objective. Images were acquired using a Nikon DXM 1200F camera and Nikon ACT-1 software version 2.62. Panels vii-xii depict the analyses of ectopic thymi from mice that have received 15 × 106 Balb/c T cells 3 weeks earlier. For analysis of ectopic T-cell development, relative numbers (in percent) of immature CD4+CD8+ and SP mature thymocytes, respectively, are shown. A total of 3 mice were analyzed for each transplantation group. The experiment was performed twice, with identical results; *P < .05 versus mice receiving no T cells.

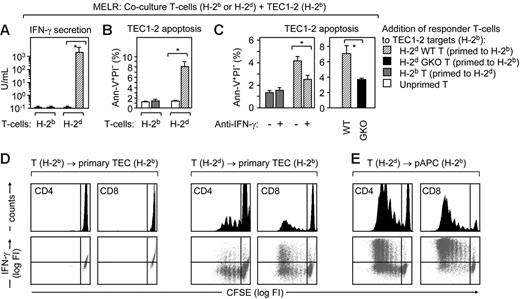

TECs elicit IFN-γ secretion by primed allospecific T cells and as a result undergo apoptosis

We next performed MELRs to answer the question whether donor T -cells could be sufficiently stimulated by allogeneic TECs to secrete IFN-γ. TEC1-2 (H-2b) cells not yet exposed to cytokines were cocultured with unprimed or primed T cells from either syngeneic B6 (H-2b) or allogeneic Balb/c (H-2d) mice. The addition of allogeneic H-2d T cells that had been primed by H-2b splenic pAPCs, secreted high levels of IFN-γ when they were subsequently exposed to TEC1.2 (Figure 4A, ▨) and also induced apoptosis of target cells (Figure 4B). The blockade of IFN-γ activity in MELR cultures either by the addition of neutralizing antibody or by the use of GKO (Balb/c-IFN-γ−/−) responder T cells (H-2d) prevented TEC1-2 apoptosis (Figure 4C). The addition of naive (unprimed) H-2d T-cells to TEC1-2 did neither result in IFN-γ secretion nor in TEC1-2 apoptosis (□). Similarly, H-2b T-cells primed by splenic H-2d pAPCs and subsequently cocultured with TEC1-2 failed to elicit programmed cell death (⊡), demonstrating the alloMHC-specificity of this assay. Taken together, these experiments proved a direct link between donor T cell-derived IFN-γ and TEC apoptosis, and demonstrated that T-cell recognition of allogeneic TECs results in the full activation of these lymphocytes.

TECs elicit IFN-γ secretion by allospecific T cells. (A-C) Balb/c T cells (H-2d; wild-type, WT) were primed to H-2b alloantigens on B6 splenic pAPCs (▨) and subsequently added to TEC1-2 cells (H-2b). IFN-γ secretion (A) and TEC1-2 apoptosis (Ann+PI− cells in panels B and C) were assessed after 72 hours of this mixed epithelial-lymphocyte (MELR) culture. As controls, B6 T cells (H-2b, primed to H-2d alloantigens), were used ⊡). The addition of unprimed B6 or Balb/c T-cells to TEC1-2 is denoted as (□). Experiments were performed 3 times. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05. (C) In the graph, TEC1-2 apoptosis was assessed after addition of a blocking anti–IFN-γ antibody during MELR, and, on the right, by the use of GKO (Balb/c-IFN-γ−/−; ▪) T cells (H-2d, primed to H-2b), 3 animals per group, *P < .05. (D) Primary TECs are sufficient to prime naïve allogeneic T cells in vitro. Reaggregation cultures of CD45−I-Ab int+high adult TECs (Figure S1) and CFSE-labeled naïve syngeneic T-cells (H-2b, left) or allogeneic T-cells (H-2d, middle) were used to detect ex vivo a graft-versus-host reaction. Top row shows histograms of CFSE fluorescence in CD4+ and CD8+ responder cells. Bottom row is the dot blot analysis of intracellular IFN-γ expression and CFSE labeling. FI indicates fluorescence intensity. As controls, CD45+, I-Ab high cells were used as hematopoietic pAPCs (E). The experiment was repeated twice, with identical results.

TECs elicit IFN-γ secretion by allospecific T cells. (A-C) Balb/c T cells (H-2d; wild-type, WT) were primed to H-2b alloantigens on B6 splenic pAPCs (▨) and subsequently added to TEC1-2 cells (H-2b). IFN-γ secretion (A) and TEC1-2 apoptosis (Ann+PI− cells in panels B and C) were assessed after 72 hours of this mixed epithelial-lymphocyte (MELR) culture. As controls, B6 T cells (H-2b, primed to H-2d alloantigens), were used ⊡). The addition of unprimed B6 or Balb/c T-cells to TEC1-2 is denoted as (□). Experiments were performed 3 times. Bars depict mean ± SD; *P < .05. (C) In the graph, TEC1-2 apoptosis was assessed after addition of a blocking anti–IFN-γ antibody during MELR, and, on the right, by the use of GKO (Balb/c-IFN-γ−/−; ▪) T cells (H-2d, primed to H-2b), 3 animals per group, *P < .05. (D) Primary TECs are sufficient to prime naïve allogeneic T cells in vitro. Reaggregation cultures of CD45−I-Ab int+high adult TECs (Figure S1) and CFSE-labeled naïve syngeneic T-cells (H-2b, left) or allogeneic T-cells (H-2d, middle) were used to detect ex vivo a graft-versus-host reaction. Top row shows histograms of CFSE fluorescence in CD4+ and CD8+ responder cells. Bottom row is the dot blot analysis of intracellular IFN-γ expression and CFSE labeling. FI indicates fluorescence intensity. As controls, CD45+, I-Ab high cells were used as hematopoietic pAPCs (E). The experiment was repeated twice, with identical results.

Alloreactive T cells are autonomously primed by TECs

Primary TECs are immunogenic in vivo.37,45 This capacity segregates with a high cell constitutive surface expression of MHC molecules30,40 which does not occur in TEC lines (Figure S1) and in epithelia from other tissues. To test whether TECs can prime naïve allogeneic T cells, we generated in vitro reaggregates of freshly isolated adult primary TECs (H-2b) and alloreactive T cells (H-2d). Under these conditions, allogeneic (but not syngeneic) TECs stimulated both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to proliferate and to produce IFN-γ (Figure 4D). This response was comparable (albeit lower) to T-cell activation by hematopoietic pAPCs (Figure 4E). Hence, primary TECs displayed an intrinsic T-cell priming ability as they stimulated naive MHC-disparate T cells in vitro to attain their specific effector functions.

Elimination of host-derived pAPCs in allogeneic recipients does not preclude TEC damage and aberrant thymic T-cell development

Because primary TECs can by themselves activate naïve alloreactive T cells to exert effector functions, the specific elimination of host hematopoietic pAPCs in allogeneic transplant recipients may therefore not preclude TEC damage. However, a link has been suggested between aGVHD-related cell injury of skin, liver, and intestinal epithelia and the presence of host DCs that prime alloreactive donor T cells.14,18 To test donor T-cell priming in the absence of allogeneic pAPCs, T cell-depleted BM cells from B6 mice were transplanted into NK-depleted and lethally irradiated BDF1 recipients. Four months after BMT, these [b⇒bd] chimeric mice displayed a virtually complete donor-type (H-2b) chimerism in primary and secondary lymphoid organs for all hematopoietically derived cells (98%-99%, data not shown) and for DCs (> 98%) and macrophages (>96%; Figure S2). The [b⇒bd] chimeras were then infused with B6.CD45.1 T-cells (15 × 106 , H-2b) and the development of GVHD was analyzed 2 to 4 weeks later. These mice were denoted 45.1+→ [b⇒bd]. The expression of H-2d alloantigens exclusively on host nonhematopoietic cells was sufficient to accumulate the transferred donor CD45.1+ T cells in the host thymus (Figure 5A). These thymus-infiltrating T cells (CD8+ > CD4+) displayed an activated phenotype at 2 weeks after infusion, that is, CD44high, CD62Llow, CD69− (Figure 5B), expressed RNA transcripts for IFN-γ (data not shown) and secreted protein at high levels either spontaneously or after restimulation with PMA/ionomycin (Figure 5C). In contrast, none or only small percentages of the host populations secreted IFN-γ (Figure 5F). Analogous to nonchimeric mice with aGVHD,22 the recipient type (ie, CD45.1−) thymocytes were reduced in total cellularity (Figure 5D) and the relative frequencies of immature DP and mature CD4 and CD8 SP cells were abnormal (Figure 5E).

Thymic donor T-cell invasion and abnormal T-cell development following inactivation of host-type pAPC. [B6→BDF1] BM chimeras (Figures S2–S3) remained untreated [b⇒bd], or received B6.CD45.1 T-cells, denoted 45.1+→ [b⇒bd]. Analysis of intrathymic CD45.1+ donor T cells (A-C) and CD45.1− host-type thymocytes (D-F). (A) Frequencies and total numbers of donor CD4+ (⊡) and CD8+ (▨) T cells at 2 to 4 weeks after T-cell infusion. For comparison, donor T-cell infiltration during aGVHD in nonchimeric mice is given (•). (B) Activation markers of thymic CD45.1+ T cells (shaded) were compared to splenic T cells from naive B6 mice (not filled). The x-axes show log FI of flow cytometric analyses. Numbers depict relative frequencies (%) of cells expressing the indicated surface marker. (C) Intracytoplasmic (i.c.) IFN-γ expression by donor-derived intrathymic T cells was detected in 8 mice per group. (D) Absolute number of host-type thymocytes in 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] (⊡) was compared to [b⇒bd] mice (□). (E) Frequencies of CD45.1− thymocyte populations. (F) Intracytoplasmic IFN-γ in CD45.1− thymocytes in the same mice shown in panel C. For panels A, D, and E, a total of 16 (controls) and 26 (aGVHD) mice were analyzed. Data were compiled from results of 6 experiments, with 2 to 4 animals per group. For panels B, C, and F, 8 mice (GVHD) and 4 mice (controls), respectively, were studied per group. *P < .05 versus controls.

Thymic donor T-cell invasion and abnormal T-cell development following inactivation of host-type pAPC. [B6→BDF1] BM chimeras (Figures S2–S3) remained untreated [b⇒bd], or received B6.CD45.1 T-cells, denoted 45.1+→ [b⇒bd]. Analysis of intrathymic CD45.1+ donor T cells (A-C) and CD45.1− host-type thymocytes (D-F). (A) Frequencies and total numbers of donor CD4+ (⊡) and CD8+ (▨) T cells at 2 to 4 weeks after T-cell infusion. For comparison, donor T-cell infiltration during aGVHD in nonchimeric mice is given (•). (B) Activation markers of thymic CD45.1+ T cells (shaded) were compared to splenic T cells from naive B6 mice (not filled). The x-axes show log FI of flow cytometric analyses. Numbers depict relative frequencies (%) of cells expressing the indicated surface marker. (C) Intracytoplasmic (i.c.) IFN-γ expression by donor-derived intrathymic T cells was detected in 8 mice per group. (D) Absolute number of host-type thymocytes in 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] (⊡) was compared to [b⇒bd] mice (□). (E) Frequencies of CD45.1− thymocyte populations. (F) Intracytoplasmic IFN-γ in CD45.1− thymocytes in the same mice shown in panel C. For panels A, D, and E, a total of 16 (controls) and 26 (aGVHD) mice were analyzed. Data were compiled from results of 6 experiments, with 2 to 4 animals per group. For panels B, C, and F, 8 mice (GVHD) and 4 mice (controls), respectively, were studied per group. *P < .05 versus controls.

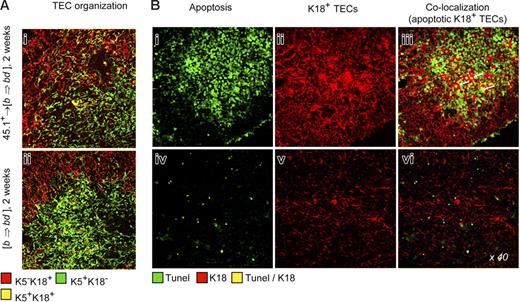

Extensive morphologic changes occurred in thymi of 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] mice that were characterized by altered architectural organization of TECs (Figure 6A). Specifically, K18+ TECs were frequently grouped in dense areas (Figure 6Bii) and thus displayed an abnormal pattern indistinguishable from that of nonchimeric mice with aGVHD.25 Moreover, a fraction of the K18+ TECs was also apoptotic (Figure 6Biii). Taken together, 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] mice developed all the hallmarks of thymic aGVHD despite the absence of allogeneic host pAPC. Signs of aGVHD were not detected in the classical target organs, liver and skin, of 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] mice (Figure S2), demonstrating that aGVHD specifically targeted the thymus in this model. Skin disease did not develop even though residual radioresistant host-type pAPCs were still present at substantial frequencies (∼7% of total pAPCs) in epidermal tissue from [b⇒bd] chimeras (Figure S2) and Merad et al.19,39 Moreover, the exposure of chimeras to UV light further reduced host DCs and macrophages but did not prevent thymic GVHD (Figure S2). Hence, peripheral activation of donor T cells by residual host DCs in the skin, and subsequent migration of T cells to the thymus, was unlikely to be a cause for TEC injury in this model. Taken together, our results suggested that TECs may suffice to prime alloreactive donor T cells not only in vitro but also in vivo and they clearly demonstrated that changes in the composition, organization, and viability of TECs as a consequence of GVHD is sufficient to cause irregular thymocyte maturation.

Abnormal TEC organization and TEC apoptosis following inactivation of host-type pAPCs. (A) Lack of a regular TEC organization in the BM chimeras described in Figure 5, as demonstrated by altered intracellular expression of K5 and K1825 at 2 weeks. (B) For analysis of apoptotic TECs, thymic sections were stained as in Figure 1. Colocalization of TUNEL and K18 depicts apoptotic TEC (arrows in panel iii). Four individual experiments were performed, with 2 to 4 animals per group and experiment. These experiments yielded comparable results, and therefore a representative photomicrograph of one mouse for each group is shown.

Abnormal TEC organization and TEC apoptosis following inactivation of host-type pAPCs. (A) Lack of a regular TEC organization in the BM chimeras described in Figure 5, as demonstrated by altered intracellular expression of K5 and K1825 at 2 weeks. (B) For analysis of apoptotic TECs, thymic sections were stained as in Figure 1. Colocalization of TUNEL and K18 depicts apoptotic TEC (arrows in panel iii). Four individual experiments were performed, with 2 to 4 animals per group and experiment. These experiments yielded comparable results, and therefore a representative photomicrograph of one mouse for each group is shown.

Discussion

The present study was designed to understand the pathways by which aGVHD impairs T-cell regeneration after alloBMT. Our work was based on previous observations that the contribution of the thymus to the patient's T-cell recovery following alloBMT is influenced by the presence of GVHD.6,10,46 Indeed, thymic stromal integrity is affected during both clinical and experimental disease,28,47–49 with TECs as a disease-relevant GVHD target.25 Because regular development of T cells is dependent on TECs,30,35 any injury to the latter following alloBMT caused by GVHD should have severe consequences on normal T-cell maturation, repertoire selection, and export. This prediction led us to investigate the cellular and molecular mechanism by which aGVHD causes TEC injury. The use of a nonablative parent→F1 transplantation model for these studies was guided by the necessity to distinguish pathogenic influences on TECs by graft-versus-host reactions from those caused by chemo/radiotherapy.

Here we describe that TECs undergo apoptosis on recognition by MHC-disparate donor T cells and we identify molecular mechanisms by which this occurs. Using an in vitro system, a direct and causative link was established between donor T-cell activation to TEC alloantigens, IFN-γ secretion, STAT-1 activation in TECs, and caspase-mediated TEC apoptosis (Figures 2 and 4). Directly testing the role of IFN-γ and its association to thymic GVHD in an in vivo situation was, however, not straightforward since a systemic abrogation of IFN-γ signaling in transplant recipients or the use of GKO donor T cells exert variable and unpredictable effects on the outcome of GHVD.20,50–55 Specifically, parental GKO donor T cells expand much more in F1 host spleens when compared to wild-type cells (data not shown and Ellison et al52 ), which may alter pathogenicity on host target tissues. We have therefore used reaggregate thymic epithelial grafts in which IFN-γ signaling was specifically ablated through loss of STAT-1 expression (Figure 3). The results from these experiments provided evidence that IFN-γ–mediated signaling is causally linked to TEC injury in vivo.

One main point of our data are also that host-type pAPCs are dispensable for induction of alloimmunity against TECs in vivo (Figure 6). This result adds weight to our finding that primary TECs display an intrinsic capacity to prime naïve, MHC-disparate T cells in vitro (Figure 4D). Under the conditions used (which were independent of a previous exposure of TECs to IFN-γ) the allogeneic TECs but not the syngeneic TECs stimulated both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production. For this reason, we propose that alloreactive T cells may also be directly activated by alloantigens presented on TECs in vivo.

Although there is no experimental system available to formally exclude indirect alloantigen presentation by donor BM-derived pAPCs, there are additional arguments in favor of a direct allorecognition of TECs: first, alloreactive T cells caused TEC injury when TECs were the sole source of alloantigens in vivo (Figures 3 and S1); second, thymus-invading donor T cells displayed an activated phenotype and secreted IFN-γ in 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] recipients (Figure 5); and third, aGVHD was localized in these chimeric mice to the site of the thymus but not to other organs (Figure S2). The view that TECs can cell-autonomously act as pAPCs for naive allogeneic T cells is in keeping with data from others using a similar parent→F1 chimera model.56,57 Here, subsets of high-affinity resting T cells were shown to become activated in vivo to class I and II alloantigens presented selectively on non-BM–derived cells. Nevertheless, our conclusion is at variance with other reports.14,58 Addressing different degrees of histoincompatibility, these latter studies indicated the requirement of host pAPCs for epithelial injury in the classical target organs skin, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. The capacity of TECs to prime naïve T cells and to be recognized as allogeneic targets may, however, be best explained by their specific qualities to act as APCs when compared to other epithelial cells that are regularly targeted by aGVHD. For instance, other work demonstrated that the E10 embryonic thymic epithelial anlage (which is naturally devoid of DCs at this point)59 is acutely rejected following their direct recognition by allogeneic T cells in vivo.45 Indeed, TECs (but not other epithelia) display a constitutive expression of MHC class I and II molecules (Figure S1) whose cell-surface density may even surpass that of DCs.40 Moreover, TECs are organized in a 3-dimensional fashion with only few epithelial cell/cell contacts, providing thus a meshwork of epithelial cells devoid of a basal membrane that renders it easily accessible for alloresponsive immune cells. Although the immunogenic potential of TECs is lower when compared to hematopoietic pAPCs in vitro (Figure 4D), these functional and phenotypic characteristics may render TECs thus sufficient to cause T-cell activation in vivo. Our conclusions further infer that naive mature T cells display the capacity to migrate to the thymus where they can be activated by TECs. Whether naive circulating T cells actually re-enter the thymus, or whether this capacity is restricted to peripherally activated T cells, is still debated, with experimental data supporting either conclusion.60–64 We found donor T cells to be located during aGVHD throughout both cortex and medulla (data not shown). This finding is in contrast to the predominantly medullary localization reported for activated T cells entering the thymus.61 Although naive (ie, CD44low) donor T cells in thymi of 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] mice could not be detected at any time point (data not shown), this fact does not refute an in situ activation of host-reactive T cells by TECs. This conclusion is based on the information (1) that intrathymic CD45.1+ T-cell numbers were extremely low at early time points after infusion, thus rendering their timely detection by flow cytometry very unlikely and (2) that intrathymic donor antihost T-cells displayed a robust early expansion phase.22 Moreover, in situ bystander activation may have further prevented detection of naive donor T cells.

Whereas the reaggregate thymic epithelial grafts demonstrated that thymic epithelium is indeed sufficient to induce in vivo T-cell responses leading to TEC apoptosis (Figures 3 and S1), this may or may not be the usual course of events in aGVHD. The present view holds that host-derived hematopoietic pAPCs are required to trigger alloimmune responses in vivo and to induce host tissue injury during aGVHD.14,15,17–19,58 Thus, it seems likely that under regular conditions (ie, the presence of host pAPC), alloreactive T cells are activated by pAPCs in the periphery, acquire the capacity to produce IFN-γ, enter the thymus as activated T cells, secrete IFN-γ, and induce TEC apoptosis. In additional experiments using “reverse” BM chimeras (ie, 45.1+→ [Ebd⇒bd]), we formally demonstrated such a role for pAPCs in TEC injury (Figure S3). These chimeras expressed the H-2d alloantigen on their pAPCs but not on TECs. On infusion of B6.CD45.1+ T cells, TEC injury and deficits in thymic T-cell development (data not shown) were clearly evident in 45.1+→ (bd⇒b) mice and the extent of aGVHD pathology was comparable to that described for nonchimeric mice.22,23,25 Thus, the expression of alloantigens on host thymic epithelium was not a prerequisite for the initiation of TEC injury, confirming previous data for other types of host epithelia.15

Our data infer that the depletion of host-derived hematopoietic pAPCs as part of pretransplant conditioning in clinical BMT will likely not prevent the activation of alloreactive donor T cells and the ensuing injury of TECs, and the generation of an aberrant peripheral T-cell compartment. Here, direct recognition of MHC-disparate TECs by donor T cells may only be preventable by donor T-cell depletion, which, in turn, has its own shortcomings.65 Furthermore, our conclusion remains to have clinical significance should TECs be destroyed in aGVHD via mechanisms involving indirect presentation (ie, possibly by residual radioresistant host pAPC or by donor BM-derived elements). Thus, our findings provide a clear rationale to establish therapeutic approaches that preserve recipient TEC organization, differentiation, and function following alloBMT. We have initiated studies addressing TEC cytoprotection using fibroblast growth factor-7 (FGF7, also called keratinocyte growth factor [KGF]). which promotes epithelial-cell proliferation and differentiation in a variety of tissues (including TECs, Werner66 and Min et al67 and Rossi et al68 . Signaling via its receptor FGFR2IIIb, whose expression in the murine thymus is restricted to TECs,25,69 FGF7 preserved the structure of the thymic microenvironment during aGVHD in mice.25 This TEC cytoprotection was achieved despite the presence of alloreactive donor T cells within the confines of the thymic microenvironment. Importantly, the integrity of the TEC network allowed for regular thymopoiesis to occur. Thus, future approaches to limit immune deficiency following alloBMT should include alloreactive donor T cells for their advantageous antileukemic effects and novel interventions to protect TEC integrity and function.

Authorship

Contribution: M.M.H. and M.P.K. contributed equally to this work and share first authorship and both designed and performed work; W.K. and G.A.H. share senior authorship, and both designed work and wrote the paper; J.G. performed microscopy and image acquisition; K.H., E.P., T.B., and A.P. performed work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Werner Krenger or Georg A. Holländer, Laboratory of Pediatric Immunology, Department of Clinical-Biological Sciences, Center for Biomedicine, University of Basel, Mattenstrasse 28, 4058 Basel, Switzerland; e-mail: werner.krenger@unibas.ch; and georg-a.hollaender@unibas.ch.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation grants 3100-61782.00 (W.K.) and 3100-68310.02 (G.A.H.), by a grant from the European Community 6th Framework Program Euro-Thymaide Integrated Project (G.A.H.), by National Institutes of Health grant ROI-A1057477-01 (G.A.H), a Roche Research Foundation grant (M.M.H.), and by the Basel Cancer League (W.K., M.P.K.).

The authors thank Drs Bruce B. Blazar, Dale I. Godfrey and Jonathan Sprent for helpful discussions.

![Figure 1. Thymic epithelial cells undergo apoptosis during aGVHD. Thymic sections from unconditioned BDF1 mice were analyzed 2 weeks after infusion of T cells from allogeneic B6.CD45.1 mice (b→bd, A-D) or syngeneic BDF1 mice (bd→bd, E-H). TUNEL+ cells among total thymic cells are shown in green (40×/0.75 numerical aperture [NA] objective). For TEC analysis, thymic sections were stained for the intracellular cytokeratin K1825 (shown in red). aGVHD in this nonirradiated model results in severe morphologic alterations in the thymic stromal microenvironment, with a loss in regular organization among K5−K18+, K5+K18− and K5+K18+ TECs (Figure S3 and Rossi et al25). The colocalization of TUNEL and K18 denotes apoptotic TECs (yellow, arrows in insets panels C and D; original magnification × 160 for panels D and H) whose detection depends also on the orientation of the epithelial cell. Areas of elevated epithelial density and TUNEL+ TECs were not seen in thymi of mice receiving syngeneic transplants. The relatively low frequency of apoptotic TECs was consistent with the established efficiency of the thymic microenvironment to remove apoptotic-cell debris and also with the high turnover of epithelial cells in situ.40,41 Four individual experiments were performed, with 2 to 4 animals per group and experiment. Because these experiments yielded comparable results, a representative photomicrograph is shown for each group.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/9/10.1182_blood-2006-07-034157/4/m_zh80090700640001.jpeg?Expires=1769866344&Signature=IxnWpEd4JTGaW~qlunArWVzPsD4pkyvwdBkSAF~tT0N2mdeyDriYlfJyFyS5JrXK8fapNtsLA0FwXGHVrvYOvqmQX3uR-WZxOX~DSSfRTvCvg75PBxhjBLTkriQrCY6o3MrYfpcAqLoAMjntCEyf1EDRHnrjGMjU77xQERK0rPGWWebQkn0DTYeGZ6-da-98~XbgZYyua4AIAt5Z23N9wB9ipBKI7xK6GSeJwrr0zl~7HtwoISuryZT5f02MpvmrpY-894vQe6YCD5FwdGXBrzhVhertTQ9b82up-Ij9-I4sl4lCwcnlqvtT~FosBXfcOQsl~heAMdTw4upV6WK8tw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 5. Thymic donor T-cell invasion and abnormal T-cell development following inactivation of host-type pAPC. [B6→BDF1] BM chimeras (Figures S2–S3) remained untreated [b⇒bd], or received B6.CD45.1 T-cells, denoted 45.1+→ [b⇒bd]. Analysis of intrathymic CD45.1+ donor T cells (A-C) and CD45.1− host-type thymocytes (D-F). (A) Frequencies and total numbers of donor CD4+ (⊡) and CD8+ (▨) T cells at 2 to 4 weeks after T-cell infusion. For comparison, donor T-cell infiltration during aGVHD in nonchimeric mice is given (•). (B) Activation markers of thymic CD45.1+ T cells (shaded) were compared to splenic T cells from naive B6 mice (not filled). The x-axes show log FI of flow cytometric analyses. Numbers depict relative frequencies (%) of cells expressing the indicated surface marker. (C) Intracytoplasmic (i.c.) IFN-γ expression by donor-derived intrathymic T cells was detected in 8 mice per group. (D) Absolute number of host-type thymocytes in 45.1+→ [b⇒bd] (⊡) was compared to [b⇒bd] mice (□). (E) Frequencies of CD45.1− thymocyte populations. (F) Intracytoplasmic IFN-γ in CD45.1− thymocytes in the same mice shown in panel C. For panels A, D, and E, a total of 16 (controls) and 26 (aGVHD) mice were analyzed. Data were compiled from results of 6 experiments, with 2 to 4 animals per group. For panels B, C, and F, 8 mice (GVHD) and 4 mice (controls), respectively, were studied per group. *P < .05 versus controls.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/109/9/10.1182_blood-2006-07-034157/4/m_zh80090700640005.jpeg?Expires=1769866344&Signature=JNECMH2nr7g9d6fgolOVDAdVMwk7bO2y~RhC1RBCbMIHUfO002yBl-GbNWzN891ISdQhFcfaMXCwKfVXft2rVT4C9KGY4onA0Kkt5nnJWwLFrLSRrzDwZUkpeIkkD-s3Ds2qGq6QPXVM6Jg0hZYERnrZtFOCeM2iPojdtydgMlFr2C1OMKHhfy2cNX9lvfia8lnpqsftdQx1jlK2xrjRbLhjYuACknLSFEJYnTOgihA3JeCU6SW74or~MT1BCvzHe1ccxKbMR3MQl74S3OCIOPdyGQGI249ox62NSYfgFO~yzmTnK~o9-Mz2swLbrMWqDJHTEgTehJWi6v~zCpyfuQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal