Abstract

Common sequence variants situated between the HBS1L and MYB genes on chromosome 6q23.3 (HMIP) influence the proportion of F cells (erythrocytes that carry measurable amounts of fetal hemoglobin). Since the physiological processes underlying the F-cell variability are thought to be linked to kinetics of erythrocyte maturation and differentiation, we have investigated the influence of the HMIP locus on other hematologic parameters. Here we show a significant impact of HMIP variability on several types of peripheral blood cells: erythrocyte, platelet, and monocyte counts as well as erythrocyte volume and hemoglobin content in healthy individuals of European ancestry. These results support the notion that changes of F-cell abundance can be an indicator of more general shifts in hematopoietic patterns in humans.

Introduction

Hematologic variables that are routinely measured for clinical purposes are influenced by the individual genetic constitution of the patients1,2 : in an ethnically homogenous population, we found that 62% of the variance in white blood cell counts, 57% of that in platelet counts, and 42% of the red cell count variance were due to genetic factors.3 The identification of the underlying genes and sequence variants will not only help to explain the variability seen between patients, but should advance our understanding of hematopoiesis in human health and disease.

HMIP (HBS1L-MYB intergenic polymorphism) refers to an array of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) situated in the interval between the gene for HBS1L (a G-protein/elongation factor) and the MYB oncogene, on chromosome 6q23.3. The physiological significance of this sequence variability was recently discovered through the investigation of persistent fetal hemoglobin synthesis in adults4 : HMIP SNPs exist in 3 linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks, HMIP-1, HMIP-2, and HMIP-3, and the genotype at each block influences the number of F cells and fetal hemoglobin (HbF) levels.4 Strong LD between the SNPS within blocks permits the selection of a single tag SNP for each block: rs52090901 for HMIP-1, rs9399137 for HMIP-2, and rs6929404 for HMIP-3. The HMIP locus accounts for approximately 17% of the variation in F-cell numbers, with most of the effect contributed by the 22-kb haplotype block 2 (HMIP-2). HMIP-2 has 2 common haplotypes, designated haplotype 1 and haplotype 2. Haplotype 2, with a frequency of 0.2 to 0.25, is associated with raised F-cell levels in white Europeans. Initial functional studies have provided evidence that the locus acts through the regulation of the flanking genes, HBS1L and MYB.4 The sequence between these genes5 and the MYB gene product itself6-8 have been shown to affect proliferation, survival, and differentiation of hematopoietic progenitor cells as well as peripheral blood cell counts in animal studies. We therefore investigated the influence of HMIP genotypes on hematologic indices in a healthy human population.

Patients and methods

One thousand seven hundred ninety-four participants of North European ancestry including 740 same-sex dizygotic twin pairs, 114 monozygotic twin pairs, and 86 singletons from the St Thomas' Hospital Twin Register9 were studied. HMIP genotypes and full blood counts were available for all participants, and additional differential blood count data for 1420 of them. Due to the recruitment strategy of the Twin Register, most individuals (95%) were female. All subjects provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the local ethics committee of St Thomas' Hospital and King's College Hospital, London (LREC no. 00-245).

Samples and data were collected over 10 years, between 1997 and 2006. All measurements were made in a routine clinical laboratory setting: dataset 1, from September 1997 to July 2000, using an H3 RTX automated blood cell analyzer (Bayer, Newbury, United Kingdom); dataset 2, February 2004 to March 2006, using an XE2100 fully automated hematology analyzer (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan). Hematologic indices (Table 1) were transformed (log, square-root, reciprocal), as appropriate, to induce approximate normality. Eosinophil and basophil counts were resistant to this procedure and were further analyzed with nonnormal distributions (P < .001). Repeat measurements were available for 551 individuals, and the mean of these results was analyzed.

Hematologic variables associated with HMIP-2 genotype

| Variable . | Median (interquartile range) . | Individuals studied, no. . | Significant* confounders . | HMIP-2 effect (β) of allele 2 (P) . | ΔVARHMIP-2, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 4.5 × 1012/L (4.27-4.74) | 1789 | Sex | −0.07424 (<.001) | 0.6 |

| MCV | 91.7 fl (88.7-95) | 1761 | Age | 0.9202 (<.001) | 1.7 |

| MCH | 29.9 pg (28.8-30.9) | 1724 | Age, sex, dataset | 15.5833 (<.001) | 2.1 |

| WBC | 5.8 × 109/L (4.8-7.1) | 1788 | Dataset | −0.02279 (.040)† | 0.8 |

| Plt | 232 × 109/L (193-274) | 1784 | Sex, dataset | 0.03908 (<.001) | 0.6 |

| Mon | 0.33 × 109/L (0.26-0.41) | 1416 | Age, dataset | −0.04163 (.004) | 1.6 |

| Variable . | Median (interquartile range) . | Individuals studied, no. . | Significant* confounders . | HMIP-2 effect (β) of allele 2 (P) . | ΔVARHMIP-2, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC | 4.5 × 1012/L (4.27-4.74) | 1789 | Sex | −0.07424 (<.001) | 0.6 |

| MCV | 91.7 fl (88.7-95) | 1761 | Age | 0.9202 (<.001) | 1.7 |

| MCH | 29.9 pg (28.8-30.9) | 1724 | Age, sex, dataset | 15.5833 (<.001) | 2.1 |

| WBC | 5.8 × 109/L (4.8-7.1) | 1788 | Dataset | −0.02279 (.040)† | 0.8 |

| Plt | 232 × 109/L (193-274) | 1784 | Sex, dataset | 0.03908 (<.001) | 0.6 |

| Mon | 0.33 × 109/L (0.26-0.41) | 1416 | Age, dataset | −0.04163 (.004) | 1.6 |

The β parameter indicates the strength and direction of HMIP-2 haplotype 2. No association was seen with traits hemoglobin concentration (Hb), packed red cell volume (PCV), mean red cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), red cell distribution width (RDW), platelet distribution width (PDW), neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and basophil counts.

ΔVARHMIP-2 indicates decrease in trait variance after fitting the HMIP-2effect; RBC, red blood cell count; MCV, mean red cell volume; MCH, mean red cell hemoglobin; WBC, white blood cell count; Plt, platelet count; and Mon, monocyte count.

Shown here when P < .05. Irrespective of their significance, the effects of all 3 potential confounders (age, sex, and dataset) were considered in the regression model.

White cell counts are not significantly associated when considering the multiple statistical testing implications of examining 6 traits.

SNP genotypes were generated by TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) at the Center National de Génotypage (Evry, France) from leukocyte DNA after genome-wide amplification (GenomiPhi; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom).

Data were initially processed in SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and then tested for association of hematologic variables with HMIP genotypes through a mixed-model ANOVA procedure (PROC MIXED) from SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), as described.4 Sex, age, dataset, and HMIP genotypes were incorporated as fixed effects; random effects modeled the residual correlation between cotwins.

Results and discussion

The most functionally active haplotype block within the HMIP region, HMIP-2, was tested for association with our panel of hematologic indices, assuming an additive (codominant) genetic action. Haplotypes were strongly associated with several red-cell indices (RBC, MCV, MCH) and platelet counts, and showed some association (P = .004) with monocyte counts (Table 1). Small dominance effects (ie, a significant deviation of heterozygotes from the homozygote midpoint) were seen with MCV and MCH only (both P = .04). Additional small effects (eg, on WBC) might be present and perhaps detectable in larger or more homogeneous datasets. In addition, what influence the HMIP-2 locus has outside of our mostly female European white study population will have to be shown separately. An independent association with the other HMIP blocks, 1 and 3, could not be detected (data not shown). The genetic association with HMIP-2 explains 0.6% (RBC), 1.7% (MCV), 2.1% (MCH), 0.6% (Plt), and 1.6% (Mon) of the total variance of the traits studied (Table 1). These results confirm that HMIP variability leads to heritable diversity in general hematopoietic patterns. The effects can be directly observed in routine blood count parameters, but HbF and F-cell abundance are the most sensitive biologic indicators of the underlying genetic processes identified to date.

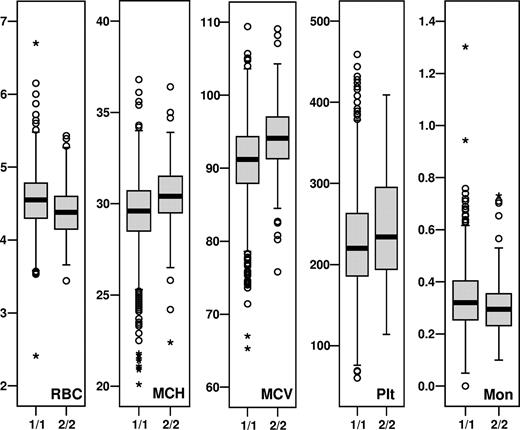

The 3 HMIP-2 genotype groups (2/2, 1/2, and 1/1) show distinct trait distributions for associated parameters, with 2/2 individuals, which make up approximately 8% of the European population under study, having markedly smaller numbers of red blood cells with larger cell volumes and higher hemoglobin content per cell, more platelets, and fewer monocytes (Figure 1). The behavior of erythrocytes and platelets in subjects with HMIP-2 2/2 phenotype in humans mirrors a mild MYB knock-down phenotype,6,8 or findings in mice with a disruption of HBS1L-MYB intergenic sequence.5 Similarly, we have previously shown that individuals with high HbF (higher than 0.8%) have a depressed expansion of erythroblasts in a 2-phase erythroid culture, and that high HbF is associated with larger erythrocyte volumes and higher platelet counts in vivo.10 HMIP-2 haplotype 2 (ie, the high-F genotype) increased the HBS1L expression in erythroblasts, but showed no detectable effect on MYB expression.4 HMIP-2 2/2 monocyte counts are low, which contrasts with our findings in the erythroid culture experiments10 and might reflect the polygenic nature of HbF regulation. The fact that HMIP-2 2/2 erythrocytes are larger and include a larger proportion of F cells4 could indicate that they are derived from earlier progenitors, similar to the situation encountered in stress erythropoiesis.11 We speculate that the locus may influence the stage of maturity of the progenitor pools from which the erythroid cells are derived; the less mature progenitors leading to higher F-cell levels. Overall, the hemoglobin concentration was unaffected by the opposing effects of the “2” haplotype on the erythrocytes (ie, lower numbers but higher hemoglobin content [MCH]).

Median and range of HMIP-2–associated variables for individuals with homozygous HMIP-2 genotypes (1/1 and 2/2). Plotted are individual measurements from dataset 1: median (▬), quartiles ( ), overall trait distribution (I), outliers (○), and extremes (+).

), overall trait distribution (I), outliers (○), and extremes (+).

Median and range of HMIP-2–associated variables for individuals with homozygous HMIP-2 genotypes (1/1 and 2/2). Plotted are individual measurements from dataset 1: median (▬), quartiles ( ), overall trait distribution (I), outliers (○), and extremes (+).

), overall trait distribution (I), outliers (○), and extremes (+).

Our study shows that common genetic factors influencing blood cell indices can be detected in humans, reaching genome-wide significance (P = 3.1 × 10−8, for RBC) with a sample size of approximately 1800 individuals. Some loci may be pleiotropic (ie, show multiple effects across different cell types). While we have used a candidate gene approach, systematic, genome-wide searches might uncover loci with stronger effects. Linkage-type studies in mice and humans have detected a series of loci for hematologic indices,12-15 with one15 detecting linkage with MCV near the HMIP locus. High-resolution mapping in heterogeneous stock mice,16 which has a resolution comparable with linkage disequilibrium mapping studies in humans, found significant peaks at a region homologous to HMIP for white cell counts, MCH, RDW, and other parameters.

We hope that this and similar studies will lead to an understanding of the genetic basis of normal blood phenotypes and will help to uncover molecular mechanisms of the regulation of hematopoiesis.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Medical Research Council (MRC) grant (G0000111, ID51640) to S.L.T. The TwinsUK project is funded by the Wellcome Trust.

We thank Helen Rooks, Ayrun Nessa, and Dimitrios Paximada for expert technical assistance.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.J., N.S., J.G., J.C., and G.S. performed research; M.F. designed the analysis approach and corrected the draft; M.L. directed research; T.D.S. contributed valuable samples; S.L.T. designed and performed research as well as wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Swee Lay Thein, Department of Haematological Medicine, King's College London School of Medicine, James Black Centre, 125 Coldharbour Lane, London, SE5 9NU, United Kingdom; e-mail:sl.thein@kcl.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal