Abstract

Chemokines, including CXCL1, participate in neutrophil recruitment by triggering the activation of integrins, which leads to arrest from rolling. The downstream signaling pathways which lead to integrin activation and neutophil arrest following G-protein–coupled receptor engagement are incompletely understood. To test whether Gαi2 is involved, mouse neutrophils in their native whole blood were investigated in mouse cremaster postcapillary venules and in flow chambers coated with P-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1. Gnai2−/− neutrophils showed significantly reduced CXCL1-induced arrest in vitro and in vivo. Similar results were obtained with leukotriene B4 (LTB4). Lethally irradiated mice reconstituted with Gnai2−/− bone marrow showed a similar defect in chemoattractant-induced arrest as that of Gnai2−/− mice. In thioglycollate-induced peritonitis and lipopolysaccaride (LPS)–induced lung inflammation, chimeric mice lacking Gαi2 in hematopoietic cells showed about 50% reduced neutrophil recruitment similar to that seen in Gnai2−/− mice. These data show that neutrophil Gαi2 is necessary for chemokine-induced arrest, which is relevant for neutrophil recruitment to sites of acute inflammation.

Introduction

Leukocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation proceeds in a multistep cascade beginning with capture and rolling, followed by arrest, adhesion strengthening, and transmigration.1,2 This process occurs as a result of molecular changes on the surface of leukocytes and endothelial cells following inflammatory stimuli. During rolling, neutrophils integrate numerous activating signals,3 resulting in β2-integrin activation, slow rolling, and arrest. Activation of β2-integrins is associated with a conformational change from a bent conformation to an extended conformation that supports slow rolling4,5 and, ultimately, to a high-affinity state that supports arrest.6,7 Arrest chemokines are presented on the surface of endothelial cells and can cause arrest of rolling leukocytes. The interaction of CXCL1 (formerly known as keratinocyte-derived chemokine [KC]) with its receptor CXCR2 on neutrophils can induce neutrophil arrest in vitro and in vivo.8,9

CXCR2 is a Gαi-coupled receptor.10 The activation of this receptor leads to the dissociation of the αi subunit from the β and γ subunits, and subsequent intracellular downstream signaling events. The Gαi family consists of the subunits Gαo, Gαi1, Gαi2, and Gαi3, which can be blocked by pertussis toxin (PTx), and Gαz, which cannot.11 Gαi2 and Gαi3 are abundantly expressed in leukocytes, and Gαi1 is expressed at low levels.12 Gαi-mediated signaling is involved in neutrophil activation, adhesion, and recruitment.9,13-15 Following activation of the G-protein–coupled receptor (GPCR), the dissociated Gβγ complex can activate phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) γ, phospholipase C (PLC)–β2, and, to a lesser extent, PLC-β3.16-18 PLC-β hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate to produce inositol triphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 mobilizes Ca2+ from nonmitochondrial stores, and DAG activates Ca2+-dependent and Ca2+-independent protein kinase C (PKC) isoenzymes. A recent in vitro study19 showed that activation of α4β1 integrin on U937 monocyte–like cells and subsequent arrest is critically dependent on the activation of PLC, IP3 receptors, increased intracellular calcium, influx of extracellular calcium, and calmodulin. Another Gβγ complex target, PI3Kγ, is not involved in neutrophil arrest in vivo, but is instead necessary for postadhesion strengthening.20 The Gαi subunits involved in neutrophil arrest following activation of Gαi-coupled receptors remain unknown.

Neutrophil recruitment into the lung is different from recruitment to other tissues in that neutrophils accumulate in the lung microcirculation partially independent of adhesion molecules,21 and may not require rolling and arrest. Nevertheless, CXCR2 is critically involved in neutrophil recruitment in different models of lung inflammation.22,23 CXCR2 on hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic cells each contributes approximately 50% to neutrophil recruitment into the lung following lipopolysaccaride (LPS) inhalation, and no neutrophil recruitment was observed when CXCR2 is absent in all cells.23 A recent study showed that Gnai2−/− mice reconstituted with Gnai2+/+ bone marrow had defective eosinophil recruitment in a model of allergic airway inflammation, suggesting that Gαi2 signaling in lung cells is necessary for eosinophil recruitment.13 The same study also reported that elimination of Gαi2 by gene targeting leads to reduced neutrophil recruitment into the lung following LPS exposure. Neutrophils from Gnai2-deficient mice show an increased migration in vitro toward a chemoattractant, but the role of Gαi2 in hematopoietic or nonhematopoietic cells in response to LPS was not determined.13

In order to test whether Gαi2 is involved in chemokine-induced arrest, autoperfused flow chambers with defined substrates and intravital microscopy of cremaster venules were used. To test the physiologic importance of Gαi2, we investigated neutrophil recruitment in models of LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation and thioglycollate-induced peritonitis. In order to distinguish between hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic Gαi2, bone marrow chimeric mice were used.

Materials and methods

Animals and generation of bone marrow chimeras

We used 8- to 12-week-old Gnai2-deficient mice and littermate control mice on the 129/Sv background.24 Genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The wild-type Gnai2 allele was detected as a 119-bp fragment using primers Ai2E6F1 (5′-GATGTTTGATGTGGGTGGTCAGC) and Ai2Ex6B (5′-TCCTCAGCCAGCACCAAGTCATAA), while the targeted allele was detected using Ai2Ex6B and PGK-2 (5′-ACTTCCTGACTAGGGGAGGAGTAGAAGGTG), yielding a 252-bp fragment. Mice were housed in a barrier facility under specific pathogen–free conditions. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Virginia approved all animal experiments. Bone marrow transplantation was performed as described previously.25 Briefly, recipient mice were lethally irradiated in 2 doses of 6 Gy (600 rad) each (separated by 4 hours). Bone marrow was isolated from donor mice under sterile conditions, and approximately 5 × 106 unfractionated cells were injected intravenously into recipient mice. Experiments were performed 6 weeks after bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

Surgical preparation and intravital microscopy

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine hydrochloride (125 mg/kg; Sanofi Winthrop Pharmaceuticals, New York, NY), atropine sulfate (0.025 mg/kg; Fujisawa, Deerfield, IL) and xylazine (12.5 mg/kg; Tranqui Ved; Phonix Scientific, St. Joseph, MO) and placed on a heating pad. After tracheal intubation and cannulation of 1 carotid artery, the cremaster muscle was prepared for intravital microscopy as previously described.26 Microscopic observations were made on postcapillary venules (diameter, 20-40 μm) using an intravital microscope (Axioskop; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a saline immersion objective (SW 40/0.75 numerical aperture). A CCD camera (model VE-1000CD; Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN) was used for recording. Images were prepared with Adobe Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Leukocyte arrest was determined before and 1 minute after intravenous injection of 600 ng CXCL1 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or 5 μg leukotriene B4 (LTB4; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) as described previously.9 Arrest was defined as leukocyte adhesion longer than 30 seconds and expressed as cells per surface area. Surface area, S, was calculated for each vessel using S = π × d × lν, where d is the diameter and lν is the length of the vessel. Blood flow centerline velocity was measured using a dual photodiode sensor and a digital on-line cross-correlation program (Circusoft Instrumentation, Hockessin, DE). Centerline velocities were converted to mean blood flow velocities by multiplying with an empirical factor of 0.625.27 Wall shear rates (γw) were estimated as 4.9 (8 vb/d), where vb is the mean blood flow velocity, d is the diameter of the vessel, and 4.9 is a median empirical correction factor obtained from velocity profiles measured in microvessels in vivo.28

Blood-perfused microflow chamber

An autoperfused flow chamber system was used to investigate neutrophil arrest as previously described.20,29 Rectangular glass capillaries (20 ×200 μm) were coated with P-selectin (20 μg/mL; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), ICAM-1 (15 μg/mL R&D Systems), and CXCL1 (15 μg/mL; PeproTech) for 2 hours and blocked for 1 hour using 10% casein (Pierce Chemicals, Dallas, TX). Each capillary was connected to a PE 10 catheter (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) inserted into the carotid artery. The other side of the chamber was connected to PE 50 tubing and used to control the wall shear stress, which was calculated as described.29 Each chamber was perfused with blood for 6 minutes before 1 representative field of view was recorded for 1 minute using an SW40/0.75 objective. In some experiments, blood was collected by cardiac puncture, and phospholipase C was blocked with the pharmacologic inhibitor U73122 (1 μM; Cayman Chemical) for 30 minutes. U-73122 is an inhibitor of PLC-dependent processes; however, the mechanism of action remains unclear.30-32

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from isolated neutrophils and lymphocytes was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed using an Omniscript kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), oligo DT primers, and 150 ng of total RNA. Real-time PCR was performed on an iCycler iQ Real-time Detection System (Qiagen) with sequence specific primers and Taqman probes designed on Beacon Designer 7 software (Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA). A total of 1 μL cDNA was used for all samples, which were run in triplicate. Values were determined using iCycler iQ Real-time Detection System Software v3.1 (Qiagen). The resulting values were normalized to GAPDH.

Murine model of LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation

As described previously,33 LPS from Salmonella enteritidis (500 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was nebulized to induce pulmonary inflammation. Briefly, mice were exposed 30 minutes to aerosolized LPS or saline aerosol as a control. At 24 hours after inhalation, mice were killed, and neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar compartment was determined by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). BAL fluid was recovered after instillation of phosphate-buffered saline (5 × 1 mL). BAL was centrifuged, and leukocytes were counted using Kimura stain. The fraction of neutrophils in the suspension was determined by flow cytometry (FACS Calibur; Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Neutrophils were identified by their typical appearance in the forward/sideways scatter (FSC/SSC) and their expression of CD45 (clone 30-F11), 7/4 (clone 7/4; both BD Biosciences-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), and GR-1 (clone RB6-8C5).

Peritonitis model

Peritoneal recruitment of leukocytes was induced using 4% thioglycollate (Sigma-Aldrich) according to previously published methods.9 After 4 hours, mice were killed, the peritoneal cavity was rinsed with 10 mL PBS (containing 2 mM EDTA), and fluid was analyzed for the number of neutrophils using Kimura staining.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS (version 14.0; Chicago, IL) and included 1-way analysis of variance, Student-Newman-Keuls test, and t test where appropriate. All data are presented as means plus or minus SEM. P levels less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

Gαi2 and PLC in neutrophils are required for neutrophil chemokine-induced arrest on P-selectin/ICAM and calcium influx

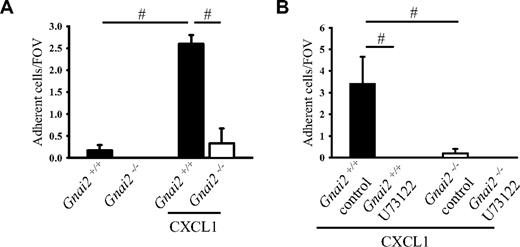

Whole native mouse blood was perfused over P-selectin and ICAM-1 coimmobilized with CXCL1 at a wall shear stress of 5.94 dyn/cm2. In a previous study, we showed that more than 90% of the rolling cells in this model are neutrophils.29 A few neutrophils from Gnai2+/+ mice, but none from Gnai2-deficient mice, adhered to P-selectin– and ICAM-1–coated flow chambers (Figure 1A). In Gnai2+/+ mice, but not in Gnai2−/− mice, neutrophil adhesion significantly increased when CXCL1 was coimmobilized with P-selectin and ICAM-1 (Figure 1A).

Gαi2 and PLC in neutrophils are required for neutrophil chemokine-induced arrest on P-selectin/ICAM-1. (A) Carotid cannulas were placed in Gnai2−/− mice (□) and Gnai2+/+ mice (■) and connected to autoperfused flow chambers coated with P-selectin and ICAM-1 alone or in combination with CXCL1 (10 μg/mL). The wall shear stress in all flow chamber experiments was 5.94 dyn/cm2. There were at least 3 mice and 4 flow chambers per group. To account for the 2.5-fold increase of neutrophils in Gnai2-deficient mice compared with littermate controls (Table 1, the number of adherent neutrophils was normalized to systemic neutrophil counts. Number of normalized adherent cells per field of view is presented as means plus or minus SEM. (B) Number of adherent neutrophils on P-selectin and ICAM-1 in combination with CXCL1 of U73122-pretreated whole blood after 6 minutes. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 3 mice. #P < .05.

Gαi2 and PLC in neutrophils are required for neutrophil chemokine-induced arrest on P-selectin/ICAM-1. (A) Carotid cannulas were placed in Gnai2−/− mice (□) and Gnai2+/+ mice (■) and connected to autoperfused flow chambers coated with P-selectin and ICAM-1 alone or in combination with CXCL1 (10 μg/mL). The wall shear stress in all flow chamber experiments was 5.94 dyn/cm2. There were at least 3 mice and 4 flow chambers per group. To account for the 2.5-fold increase of neutrophils in Gnai2-deficient mice compared with littermate controls (Table 1, the number of adherent neutrophils was normalized to systemic neutrophil counts. Number of normalized adherent cells per field of view is presented as means plus or minus SEM. (B) Number of adherent neutrophils on P-selectin and ICAM-1 in combination with CXCL1 of U73122-pretreated whole blood after 6 minutes. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 3 mice. #P < .05.

Systemic leukocyte blood counts

| . | Leukocytes, × 109 cells/L . | Neutrophils, × 109 cells/L . | Lymphocytes, × 109 cells/L . | Monocytes, × 109 cells/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnai2+/+ | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Gnai2−/− | 24.2 ± 5.3* | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 18.8 ± 3.2* | 2.8 ± 2.0 |

| Gnai2+/+ → Gnai2+/+ | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 2.2* | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| . | Leukocytes, × 109 cells/L . | Neutrophils, × 109 cells/L . | Lymphocytes, × 109 cells/L . | Monocytes, × 109 cells/L . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gnai2+/+ | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| Gnai2−/− | 24.2 ± 5.3* | 2.5 ± 1.7 | 18.8 ± 3.2* | 2.8 ± 2.0 |

| Gnai2+/+ → Gnai2+/+ | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.4 |

| Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ | 13.2 ± 2.5 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 10.7 ± 2.2* | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

Leukocyte, neutrophil, lymphocyte, and monocyte counts are of at least 5 mice per group. Data are presented as mean plus or minus SEM.

P < .05 versus Gnai2+/+.

PLC can be activated by the Gβγ complex following activation of GPCRs and is involved in the regulation of the integrin affinity state and arrest of monocyte-like U937 cells.19 In order to address whether PLC is also involved in chemokine-induced arrest of primary mouse neutrophils, neutrophil arrest was investigated in the flow chamber system following blocking of PLC by incubating whole blood with a pharmacologic inhibitor. Incubation of blood from Gnai2+/+ mice with the PLC inhibitor U73122 completely eliminated neutrophil arrest in flow chambers coated with P-selectin, ICAM-1, and CXCL1 (Figure 1B).

Reduced chemokine-induced arrest in cremaster venules of Gnai2-deficient mice in vivo

In order to confirm our in vitro data in vivo, we conducted intravital microscopy of the cremaster muscle. In the acutely exteriorized mouse cremaster, neutrophils roll along the endothelium of venules, but neutrophil adhesion is almost absent.26 Neutrophil rolling in this model is known to be mediated by P-selectin.26 Injection of the recombinant murine chemokine CXCL1, which binds and activates CXCR2, induced immediate firm arrest in Gnai2+/+ mice (Figure 2A). Gnai2−/− mice showed the same number of adherent neutrophils under baseline conditions as Gnai2+/+ mice when accounting for their elevated blood neutrophil numbers. In contrast to Gnai2+/+ mice, the number of adherent cells per area in Gnai2−/− mice did not increase after CXCL1 injection (Figure 2A). Representative video micrographs of Gnai2+/+ mice and Gnai2−/− mice before and after CXCL1 treatment are shown in Figure 2B. Wall shear rates and diameters were similar in the investigated venules, excluding a hemodynamic contribution to reduced neutrophil adhesion (data not shown).

Reduced chemokine-induced arrest in cremaster venules of Gnai2-deficient mice in vivo. (A) Number of adherent cells (normalized to blood neutrophil counts) in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice and littermate control mice after intravenous injection of 600 ng CXCL1. Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented are the means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. (B) Representative pictures of cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2+/+ and Gnai2−/− mice before and 1 minute after CXCL1 injection (leukocytes are circuited: rolling leukocytes, · · ·; arrested leukocytes, —). Scale bar equals 10 μm. (C-D) Adherent leukocytes in postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice (D) or littermate control mice (C) after injection of CXCL1. Each line represents the number of adherent leukocytes per square millimeter in 1 venule of 1 mouse after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. #P < .05.

Reduced chemokine-induced arrest in cremaster venules of Gnai2-deficient mice in vivo. (A) Number of adherent cells (normalized to blood neutrophil counts) in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice and littermate control mice after intravenous injection of 600 ng CXCL1. Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented are the means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. (B) Representative pictures of cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2+/+ and Gnai2−/− mice before and 1 minute after CXCL1 injection (leukocytes are circuited: rolling leukocytes, · · ·; arrested leukocytes, —). Scale bar equals 10 μm. (C-D) Adherent leukocytes in postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice (D) or littermate control mice (C) after injection of CXCL1. Each line represents the number of adherent leukocytes per square millimeter in 1 venule of 1 mouse after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. #P < .05.

Previous studies have shown that some interventions, such as blocking PI3Kγ,20 Vav1 and Vav3,34 or Src kinases,35 impair postadhesion strengthening, which leads to neutrophil detachment after adhesion. To test whether neutrophils from Gnai2−/− mice have an arrest defect or a postadhesion strengthening defect, adherent neutrophils were tracked after CXCL1 injection. In Gnai2+/+ mice, neutrophils adhered rapidly to the endothelium following CXCL1 injection and remained attached over the next minute (Figure 2C). Gnai2−/− mice showed also rapid arrest after CXCL1 injection, but at much lower numbers (Figure 2D). Adhesion stability was unaffected. These data demonstrate that Gαi2 signaling is required for neutrophil arrest but is probably not involved in adhesion strengthening.

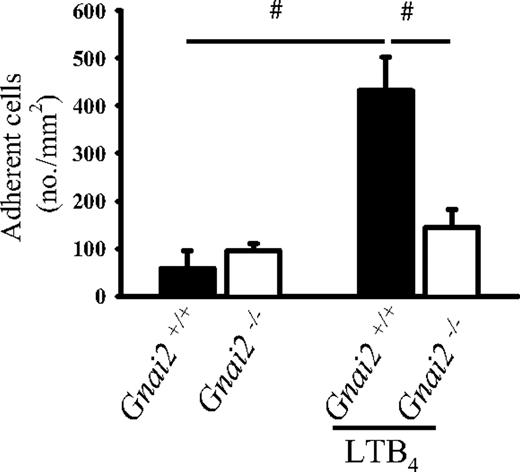

Gnai2-deficient mice cannot induce leukocyte arrest in postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle in response to LTB4

In order to extend our findings to a different chemoattractant receptor, we used LTB4, which binds to and activates BLTR1, a Gαi-coupled receptor.36 LTB4 induced leukocyte arrest in Gnai2+/+ mice (Figure 3). However, in Gnai2−/− mice, LTB4 induced very little leukocyte adhesion. To test possible compensatory mechanisms in these mice, we measured mRNA for Gαi3 by real-time RT-PCR and found no evidence for up-regulation in Gnai2−/− mice (data not shown).

Gnai2-deficient mice cannot induce leukocyte arrest in postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle in response to LTB4. Number of adherent leukocytes in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice and Gnai2+/+ mice after intravenous injection of 5 μg LTB4. Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. #P < .05.

Gnai2-deficient mice cannot induce leukocyte arrest in postcapillary venules of the cremaster muscle in response to LTB4. Number of adherent leukocytes in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice and Gnai2+/+ mice after intravenous injection of 5 μg LTB4. Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from 4 mice. #P < .05.

Gαi2 in neutrophils is responsible for chemokine-induced neutrophil arrest

The autoperfused flow chamber data suggested that neutrophil Gαi2 is required for CXCL1-induced arrest. To directly test the role of neutrophil Gαi2 in chemokine-induced arrest in vivo, bone marrow from Gnai2-deficient mice was transplanted into lethally irradiated Gnai2+/+ mice. In these mice, bone marrow–derived cells lack Gαi2, but endothelial and other cells express Gαi2. Leukocyte arrest in response to intravenous CXCL1 was investigated by intravital microscopy in postcapillary cremaster venules 6 to 8 weeks after transplantation. CXCL1 induced leukocyte adhesion in Gnai2+/+ control mice. In Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice, CXCL1-induced neutrophil arrest was significantly reduced but not abolished (Figure 4).

Gαi2 in neutrophils is responsible for chemokine-induced neutrophil arrest. Number of adherent leukocytes in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice and Gnai2+/+ mice after intravenous injection of 600 ng CXCL1 (normalized for blood neutrophil counts). Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from at least 4 mice.

Gαi2 in neutrophils is responsible for chemokine-induced neutrophil arrest. Number of adherent leukocytes in cremaster muscle postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice and Gnai2+/+ mice after intravenous injection of 600 ng CXCL1 (normalized for blood neutrophil counts). Data were recorded and analyzed for 1 minute starting 15 seconds after CXCL1 injection. Data presented as means plus or minus SEM from at least 4 mice.

Neutrophil recruitment in a model of LPS-induced lung inflammation, and thioglycollate-induced peritonitis is partially dependent on Gαi2 in neutrophils

Previous studies have shown that blocking of Gαi by PTx reduced neutrophil recruitment into inflamed tissue.9,15 However, PTx treatment blocks hematopoietic as well as nonhematopoietic Gαi. In view of recent findings of an important role for Gαi213 and CXCR223 in nonhematopoietic cells, we wished to differentiate between the role of hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic Gαi2 for neutrophil recruitment. We used bone marrow chimeric mice to investigate neutrophil recruitment. In a model of LPS-induced lung inflammation, Gnai2+/+ mice showed a significant increase of neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar compartment 24 hours after LPS inhalation (Figure 5A). Neutrophil influx was reduced by approximately 50% in Gnai2+/+ mice that were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with Gnai2−/− bone marrow (Figure 5A). Control mice receiving Gnai2+/+ bone marrow showed no recruitment defect. To test the physiologic importance of Gαi2 in bone marrow–derived cells in a second model, we investigated thioglycollate-induced peritonitis. Neutrophil influx into thioglycollate-induced peritonitis was significantly reduced in Gnai2−/− compared with Gnai2+/+ mice (Figure 5B). Bone marrow chimeric mice that had received Gnai2−/− bone marrow showed a similar decrease of neutrophil recruitment into the peritoneal cavity as Gnai2−/− mice (Figure 5B). These data show that neutrophil Gαi2 is relevant in vivo.

Neutrophil recruitment in a model of LPS-induced lung inflammation and thioglycollate-induced peritonitis is partially dependent on Gαi2 in neutrophils. (A) Neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar compartments of the lung with or without LPS inhalation (24 hours) was determined by flow cytometry. Gnai2−/− mice, Gnai2+/+ mice, and Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice showed different recruitment patterns of neutrophils in the alveolar compartment (n = 4). Data are means plus or minus SEM. (B) Peritoneal neutrophil influx 4 hours after injection of 4% thioglycollate into Gnai2−/− mice (4 mice), Gnai2−/− mice (3 mice), Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice (5 mice), and Gnai2+/+ → Gnai2+/+ mice (5 mice). Total number of neutrophils (× 106) in the peritoneal cavity counted using Kimura-stained samples. Horizontal bars are means of 5 replicates. *P < .05 versus other groups; #P < .05.

Neutrophil recruitment in a model of LPS-induced lung inflammation and thioglycollate-induced peritonitis is partially dependent on Gαi2 in neutrophils. (A) Neutrophil recruitment into the alveolar compartments of the lung with or without LPS inhalation (24 hours) was determined by flow cytometry. Gnai2−/− mice, Gnai2+/+ mice, and Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice showed different recruitment patterns of neutrophils in the alveolar compartment (n = 4). Data are means plus or minus SEM. (B) Peritoneal neutrophil influx 4 hours after injection of 4% thioglycollate into Gnai2−/− mice (4 mice), Gnai2−/− mice (3 mice), Gnai2−/− → Gnai2+/+ chimeric mice (5 mice), and Gnai2+/+ → Gnai2+/+ mice (5 mice). Total number of neutrophils (× 106) in the peritoneal cavity counted using Kimura-stained samples. Horizontal bars are means of 5 replicates. *P < .05 versus other groups; #P < .05.

Discussion

Many studies have shown that GPCRs are involved in triggering neutrophil arrest under flow,9,20,37-39 but the specific Gα subunit used was not known. Here, we demonstrate that Gαi2 in neutrophils is required for chemokine-induced arrest under flow in response to CXCL1. The physiologic importance of Gαi2 in bone marrow–derived cells is demonstrated by significant defects in neutrophil recruitment in an LPS-induced model of lung inflammation and in thioglycollate-induced peritonitis.

In a recent study, Pero et al showed that eosinophil recruitment in a model of allergic airway inflammation was almost abolished in mice lacking Gαi2.13 The trafficking defect could not be restored when Gnai2−/− mice were reconstituted with Gnai2+/+ bone marrow, suggesting that endothelial cell Gαi2 was required for transmigration. In the same study,13 a neutrophil recruitment defect was seen in Gnai2−/− mice in an LPS-induced model of lung inflammation, but the role of Gαi2 on bone marrow–derived cells and other cells was not addressed separately. In a study of CXCR2−/− mice, CXCR2 was found to be required on both neutrophils and endothelial cells in order to support optimal neutrophil recruitment to the bronchoalveolar space in response to aerosolized LPS.23 The present results demonstrate that Gαi2 is also required on both bone marrow–derived and other cells for neutrophil recruitment in LPS-induced lung inflammation. The reason for the greater importance of endothelial cell Gαi2 and lesser importance of eosinophil Gαi2 in eosinophil recruitment in allergic airway inflammation13 remains to be explored.

Gαi-coupled GPCRs are involved in many biological functions of neutrophils, including adhesion,9 triggering the respiratory burst,40 degranulation,41 and actin polymerization.42 The focus of the present study was on neutrophil arrest, one of the earliest steps in the inflammatory adhesion cascade.1,2 Although our findings of reduced neutrophil recruitment into the inflamed lung and peritoneal cavity of mice reconstituted with Gnai2−/− bone marrow are consistent with the observed arrest defect, it is possible that defective chemotaxis and transendothelial migration of Gnai2−/− neutrophils also contribute to the observed phenotype. Since neutrophil availability in the blood, arrest, and chemotactic migration are considered sequential events, the disturbance of one of these factors can modulate the recruitment of neutrophil into the tissue. In the case of LPS-induced lung inflammation, this is indeed likely, because CXCR2 is not required for neutrophil accumulation in the lung vasculature.23 The lung microcirculation has very small capillaries, allowing neutrophils to lodge even without adhesion mechanisms.21 Gαi2 is also critically involved in chemokine receptor signaling in lymphocytes.43,44 B-44 and T-lymphocytes43 from Gnai2-deficient mice show reduced chemotaxis and homing to lymph nodes. The more severe increase of lymphocyte numbers than that of neutrophil numbers in Gnai2-deficient mice suggests that lymphocytes rely more on chemokine signals than neutrophils.

Our study establishes Gαi2 as the most important Gα subunit in chemoattractant-induced neutrophil arrest. This is consistent with previous work9 showing that neutrophil arrest is blocked by PTx, an intervention that blocks all Gαi signaling. However, it remains unclear whether Gαi2 directly triggers downstream signaling events, or whether it releases a specific subset of Gβγ subunits that are uniquely suited to activate other signaling molecules. A recent study showed that PLC is required for rapid arrest in response to chemokine stimulation of monocyte-like U937 cells.19 Our study extends these findings to neutrophils and strongly suggests that Gβγ subunits released by Gαi2, but not Gαi3, are able to activate PLC. The specific PLC isoform involved and the signaling steps downstream from PLC that ultimately link GPCRs to integrin activation remain to be determined.

Gnai2−/− mice clearly have residual neutrophil function, but blood neutrophil numbers are elevated in these mice. Elevated neutrophil counts are a typical compensatory response to neutrophil recruitment defects.45,46 Indeed, microvessels in Gnai2−/− mice contain more adherent neutrophils than those of normal mice.13 This suggests that alternative, GPCR-independent adhesion mechanisms are important for neutrophil recruitment. One such mechanism is triggered by E-selectin binding to PSGL-1, which leads to LFA-1 activation through a pathway that requires spleen tyrosine kinase.5 Another GPCR-independent pathway for neutrophil activation during rolling requires ESL-1 and CD44.47 It is likely that these GPCR-independent mechanisms account for at least some of the residual neutrophil recruitment seen in Gnai2−/− mice. Interestingly, Gαi2 does not appear to be involved in postarrest adhesion strengthening. This step involves integrin rearrangement in the plasma membrane, clustering, and outside-in signaling.48,49 The few neutrophils that arrest in postcapillary venules of Gnai2−/− mice are just as firmly adhered as wild-type neutrophils, suggesting that the GPCR-independent neutrophil activation pathways are fully capable of producing stable adhesion in vivo. This is in contrast to observations in reconstituted flow chamber systems, where E-selectin engagement of PSGL-1 can only trigger partial activation of LFA-1, which induces slow rolling, but not arrest.5 These data suggest that some unknown, additional neutrophil activating signal(s) seem to be present in vivo. The present data show that these additional signals function independent of Gαi2.

Leukocyte arrest under flow is usually triggered by surface-immobilized chemokines,50,51 but soluble chemoattractants are equally effective. For example, fMLP injected intravenously induces immediate arrest.39 Here, we show that at least one soluble chemoattractant, LTB4, also uses Gαi2 to trigger arrest. Since the inhibition of arrest was not complete, it is possible that BLTR1, the receptor for LTB4, coupled to another G-protein different from Gαi2 that may be responsible for the residual effect.

Our study establishes Gαi2 as the main G-protein α subunit required for chemoattractant-induced neutrophil arrest in vitro and in vivo. Further studies will be required to fully unravel the signaling pathway that links GPCRs to integrin activation in neutrophils.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AZ 428/2–1 to A.Z.), from American Heart Association (AHA 0625421 U to T.L.D.), and from the National Institutes of Health (NIH HL 73361 to K.L.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: A.Z. designed experiments, performed research, and wrote the paper; T.L.D. performed flow chamber experiments; T.L.B. performed RT-PCR; and K.L. designed experiments and wrote parts of the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Klaus Ley, Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Virginia Health System, Charlottesville, VA 22908-1394; e-mail:klausley@virginia.edu, Klaus@Liai.org

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal