Abstract

In addition to its physiologic role as central regulator of the hematopoietic and reproductive systems, the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is pathologically overexpressed in some forms of leukemia and constitutively activated by oncogenic mutations in mast-cell proliferations and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. To gain insight into the general activation and signaling mechanisms of RTKs, we investigated the activation-dependent dynamic membrane distributions of wild-type and oncogenic forms of Kit in hematopoietic cells. Ligand-induced recruitment of wild-type Kit to lipid rafts after stimulation by Kit ligand (KL) and the constitutive localization of oncogenic Kit in lipid rafts are necessary for Kit-mediated proliferation and survival signals. KL-dependent and oncogenic Kit kinase activity resulted in recruitment of the regulatory phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) subunit p85 to rafts where the catalytical PI3-K subunit p110 constitutively resides. Cholesterol depletion by methyl-β-cyclodextrin prevented Kit-mediated activation of the PI3-K downstream target Akt and inhibited cellular proliferation by KL-activated or oncogenic Kit, including mutants resistant to the Kit inhibitor imatinib-mesylate. Our data are consistent with the notion that Kit recruitment to lipid rafts is required for efficient activation of the PI3-K/Akt pathway and Kit-mediated proliferation.

Introduction

Kit is a member of the type III subclass of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), which also includes the platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) α and β, Flt3, and the CSF1R (c-fms, macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor [M-CSFR]). The Kit protein is organized as an N-terminal extracellular domain containing 5 Ig-like domains, a transmembrane domain, and a cytoplasmic domain. The cytoplasmic domain contains a split catalytic domain, which is activated by ligand-mediated receptor dimerization. Loss-of-function mutations of Kit in mice result in the dominant W spotting defect, which is marked by defective pigmentation, hematopoiesis, and gametogenesis.1,2 The severity of the phenotype of W mice is related to the degree of loss of Kit expression and function. Kit ligand (KL) is produced by stromal cells in either membrane-bound or soluble isoforms.3 Loss-of-function mutations of the KL locus result in the Steel (Sl) phenotype closely resembling that of W mouse strains.4

Oncogenic Kit can broadly be categorized as caused by mutations in the juxtamembrane region that cause ligand-independent dimerization (dimerizing mutants), or mutations in the carboxyl-terminal segment of the kinase domain that cause constitutive enzymatic activity (catalytic mutants).5 Dimerizing mutants have been observed in gastro-intestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), a rare malignancy of mesenchymal cells in the gut.6 A mouse model of a GIST demonstrated that constitutive Kit signaling through a dimerizing mutant is necessary and sufficient for hyperplasia of interstitial cells of Cajal and induction of a GIST.7 Catalytic Kit mutants have been more commonly associated with mastocytosis.8 Treatment of GISTs has been significantly improved by the introduction of imatinib-mesylate (referred to hereon as imatinib),9 a small molecule inhibitor of Kit tyrosine kinase activity10 that was originally developed as an inhibitor of the tyrosine kinase activity of the Bcr-Abl fusion oncogene in chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).11 However, only Kit-dimerizing mutants are broadly responsive to imatinib and, as observed in CML, the development of imatinib resistance in GIST patients is a serious problem and requires further therapeutic improvement, eg, combination with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors.12

Among the various signaling pathways activated by wild-type Kit, the Src family kinase (SFK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathways have been studied in vivo by murine knock-in models. In vitro, SFKs have been shown to be necessary for Kit-mediated proliferation and chemotaxis.13 Kit-mediated activation of SFKs regulates early lymphopoiesis.14 On the other hand, gametogenesis was shown in vivo to depend on Kit-mediated activation of PI3-K.15 Oncogenic Kit resembles signaling through wild-type Kit in that SFKs and PI3-K are both activated, the latter having been shown to be necessary for cellular transformation by catalytic Kit mutants.16 For other pathways, there appear to be certain differences in substrate specificity between wild-type and oncogenic Kit.17

Recent studies of other receptor systems have demonstrated the importance of localization of receptors at high density into plasma membrane microdomains or lipid rafts. For example, the multimeric T-cell receptor (TCR) and associated signaling molecules are recruited to lipid rafts upon engagement of the TCR with cognate ligands composed of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and peptides.18 Lipid rafts are characterized by the presence of high levels of cholesterol, sphingolipids, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked proteins and contain signaling molecules like SFKs.19,20 By virtue of their lipid content that is different from the membrane, these domains can be physically isolated as detergent-insoluble glycolipid-containing fractions upon ultracentrifugation of cell extracts19 and have been visualized as discrete areas of varying size within the cell membrane via GM1-specific binding to the cholera toxin B subunit.21 Lipid raft-dependent signaling can be abrogated by methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD), which depletes the rafts of essential cholesterol molecules.22 In addition, genetic defects, such as Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, may interfere either with the formation of rafts or the process of recruitment of proteins into lipid rafts in lymphocytes.23 Like TCR signaling, Kit signaling involves recruitment of multiple substrate proteins to the cytoplasmic domain to form an activated receptor complex. Previous work has suggested that internalization of Kit after ligand engagement depends on lipid raft formation, as disruption of lipid rafts prevents the endosomal translocation of a functional chimeric Kit fused to the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP).24 In support of this hypothesis, lipid rafts have recently been implicated in clathrin-independent endocytosis.25

We examined whether lipid rapid recruitment occurred in the course of Kit signaling and whether rafts were necessary for interactions of Kit with downstream targets that mediate survival and proliferation signals, with emphasis on SFK and PI3-K signaling.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

Recombinant human KL, human interleukin-3 (IL-3), and murine IL-3 were purchased from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, and Biosource International, Camarillo, CA. Antibodies against Kit, Flotillin-1, ERK2, Hck, Lck, Fyn, Syk, p110, and Shc were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA. Antibodies against Lyn, phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, p85, PDK1, and PTEN were from Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). The antibody against Na/K ATPase was purchased from Novus Biochemicals (Littleton, CO) and Upstate (Lake Placid, NY). The antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibodies 4G10 and PY20 were purchased from Upstate Laboratory (Syracuse, NY) and Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY), respectively.

Cell culture and media

Mo7e and Ba/F3 cells were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms and Animal Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany. The HMC-1 cell line was kindly provided by J. H. Butterfield, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. HMC-1 cells have been reported to be compound heterozygotes for KitV560G and KitD816V.26 Sequencing of Kit cDNA from the HMC-1 cells used in these experiments revealed the sole presence of the KitV560G mutation (data not shown). Cells were cultured in RPMI (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA) in the presence of human KL and IL-3 (Mo7e) or murine IL-3 (Ba/F3), each at a concentration of 25 ng/mL. HMC-1 cells were cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM) (Cambrex Bio Science, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 10% FCS. Cell culture-tested MβCD was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Before measurements of cellular proliferation, Mo7e cells were cultured in absence of KL and IL-3 for 12 hours, and thymidine incorporation was measured over a time period of 12 hours in 96-well tissue culture plates at a concentration of 50 000-100 000 cells per well and 100 μL of media containing 1μCi 3H-thymidine.

Expression constructs

The murine Kit expression constructs generated by site-directed mutagenesis have been described.27 Ba/F3 cells stably expressing murine KitV558G or KitD814V were generated by electroporation and subsequent selection with Zeocin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Isolation of lipid raft, membrane, and cytosol fractions

Subcellular fractionation was performed as described18 with some minor adaptations. At the indicated time points, 108 Mo7e or HMC-1 cells were separated in 2 equal aliquots to obtain the lipid raft and the membrane/cytosol fractions. Isolation of lipid rafts was done by lysing the cells in 25 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) (pH 6.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 10 μg/mL aprotinin and protease inhibitors (Complete, Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and 10 strokes of a loose-fitting Dounce homogenizer (Wheaton, Milleville, NJ). Lysates were mixed with an equal volume of 85% sucrose, 25 mM MES (pH 6.5), and 150 mM NaCl, and overlaid with 6 mL of 35% sucrose, 25 mM MES (pH 6.5), 150 mM NaCl and 3 mL of 5% sucrose, 25 mM MES (pH 6.5), and 150 mM NaCl, all containing 1 mM Na3VO4 and 10 μg/mL aprotinin. The lipid raft fraction was collected in a total volume of 1.5 mL after centrifugation using an SW41 rotor for 16 hours, 200 000g, 4°C as interphase between the 35% and 5% sucrose layers. Membrane and cytosolic fractions were obtained by lysing the cells by 15 strokes of a loose-fitting Dounce homogenizer in 1 mL of homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL aprotinin, and Complete protease inhibitors). The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of homogenization buffer, homogenized, and centrifuged again. Both supernatants were combined, and the cytosolic fraction was obtained by diluting 0.5 mL of the lysate with 1 mL homogenization buffer and collecting the supernatant after centrifugation in an SW50.1 rotor for 1 hour at 300 000g at 4°C. To obtain the membrane fraction, 30% Percoll in homogenization buffer was overlaid with 1.5 mL of the homogenate and centrifuged using an SW41 rotor for 38 minutes, 85 000g, 4°C. The membrane fraction was collected in a total volume of 1.5 mL as an opaque band in the upper third of the Percoll gradient. After dilution of the fractions with 2× SDS gel-loading buffer, 90-110 μL was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS/PAGE) and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB).

Immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting

Immunoprecipitations (IPs) and IBs were performed as described.24,27 In brief, cells were harvested in cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 1 mM sodium vanadate (Sigma), pelleted, and lysed in lysis buffer (1-2 × 107 cells/mL) containing 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 150 mM NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100. Proteinase inhibitor cocktail tablets (Complete, Roche, Indianapolis, IN) were added according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After clarification by centrifugation and preclearing with Protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ), 4 μg to 8 μg of antibody was used per IP, and antibody-protein complexes were collected with 50 μL of Protein A-Sepharose.

IPs of Kit or tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins from lipid raft fractions were done by resolubilizing 0.5 mL of the lipid raft fractions with 2× lysis buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4/10 mM EDTA/300 mM NaCl/2% Triton X-100) to a total volume of 1.0 mL. Diluted samples underwent 2 freeze/thaw cycles, were vortexed vigorously, and spun down in a table top-cooled microcentrifuge at 20 000g for 30 minutes. Supernatants were used to perform IPs of Kit (using an anti-Kit antibody) or phosphorylated proteins (using an anti-phosphotyrosine [PY] antibody).

Total cell lysates, bound fractions of precipitates, or lysates obtained from the subcellular fractionation procedures were subjected to SDS/PAGE (Hoefer, Amersham Pharmacia), and blotting was performed on poly(vinylidene difluoride) (PVDF) membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were incubated with primary antibodies as indicated. After washing with PBS, 0.05% Tween-20, blots were incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled secondary antibodies (antimouse) or HRP coupled to Protein A (Amersham Pharmacia) and developed using SuperSignal chemoluminescent substrates (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL).

Results

Kit is recruited to lipid rafts as a result of KL stimulation

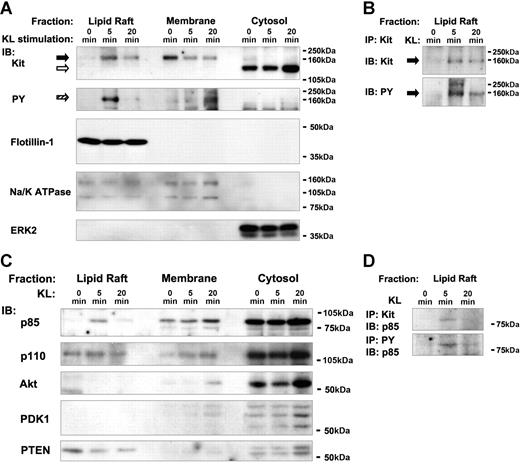

Lipid raft, membrane, and cytosol fractions were obtained from untreated Mo7e cells and cells stimulated with KL for 5 and 20 minutes. To determine whether Kit distribution in rafts was dynamic, subcellular fractions were analyzed for Kit protein and tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit by Western blotting (Figure 1A). In unstimulated cells, Kit was present predominantly within the membrane fraction (Figure 1A solid arrow). A band of smaller molecular mass of unknown origin was detected in the cytosol (Figure 1A open arrow). Only trace amounts of Kit were detected in lipid rafts before stimulation. After 5 minutes of stimulation with KL, the Kit protein appeared in the lipid raft fraction, while levels of Kit in the membrane were decreased. After 20 minutes of KL stimulation, Kit levels in the lipid rafts decreased, and Kit was present in the lipid raft and the membrane fraction in approximately equal amounts. The Kit protein localized in the lipid raft fraction after 5 minutes of KL stimulation comigrated exactly with a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein, inferring that this was tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit (Figure 1A striped arrow). At 20 minutes, the levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit were reduced in lipid rafts, and tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit appeared at higher levels in the membrane.

Dynamic localization of Kit and regulators of PI3K signaling after KL stimulation. (A,B) Kit is recruited to lipid rafts as a result of KL stimulation. (A) Subcellular fractions from unstimulated or KL-stimulated Mo7e cells (5 and 20 minutes), were isolated and immunoblotted with antibodies against Kit and PY. The signaling competent form of Kit and the tyrosine-phosphorylated protein comigrating with Kit are indicated by  and

and  , respectively. A protein of somewhat lower molecular mass cross-reacting with the anti-Kit antibody was observed in the cytosol and possibly represents a cytosolic Kit degradation product (⇨). For control of the fractionation procedure, subcellular fractions were also analyzed with antibodies against markers of the lipid raft (Flotillin-1), plasma membrane (Na/K ATPase), and cytosol (ERK2) fractions. (B) Verification of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit in lipid rafts by IP. Because the data in A consist of an immunoblot that can only be used to infer that the approximately 160-kDa-phosphorylated band is Kit, an IP of lipid raft-localized Kit from resolubilized lysates was performed and analyzed with antibodies against Kit and PY. The coprecipitating, tyrosine-phosphorylated band of significantly higher molecular mass than Kit is of unknown origin. (C) Recruitment of p85 into lipid rafts, redistribution of the negative regulator PTEN from lipid rafts to the cytosol. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against the p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunits of PI3K, PTEN, Akt and PDK1. (D) Complex formation between Kit and p85 in lipid rafts and verification of tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. As in B, an IP of Kit and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins from lipid rafts was performed and analyzed with an antibody against p85.

, respectively. A protein of somewhat lower molecular mass cross-reacting with the anti-Kit antibody was observed in the cytosol and possibly represents a cytosolic Kit degradation product (⇨). For control of the fractionation procedure, subcellular fractions were also analyzed with antibodies against markers of the lipid raft (Flotillin-1), plasma membrane (Na/K ATPase), and cytosol (ERK2) fractions. (B) Verification of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit in lipid rafts by IP. Because the data in A consist of an immunoblot that can only be used to infer that the approximately 160-kDa-phosphorylated band is Kit, an IP of lipid raft-localized Kit from resolubilized lysates was performed and analyzed with antibodies against Kit and PY. The coprecipitating, tyrosine-phosphorylated band of significantly higher molecular mass than Kit is of unknown origin. (C) Recruitment of p85 into lipid rafts, redistribution of the negative regulator PTEN from lipid rafts to the cytosol. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against the p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunits of PI3K, PTEN, Akt and PDK1. (D) Complex formation between Kit and p85 in lipid rafts and verification of tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. As in B, an IP of Kit and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins from lipid rafts was performed and analyzed with an antibody against p85.

Dynamic localization of Kit and regulators of PI3K signaling after KL stimulation. (A,B) Kit is recruited to lipid rafts as a result of KL stimulation. (A) Subcellular fractions from unstimulated or KL-stimulated Mo7e cells (5 and 20 minutes), were isolated and immunoblotted with antibodies against Kit and PY. The signaling competent form of Kit and the tyrosine-phosphorylated protein comigrating with Kit are indicated by  and

and  , respectively. A protein of somewhat lower molecular mass cross-reacting with the anti-Kit antibody was observed in the cytosol and possibly represents a cytosolic Kit degradation product (⇨). For control of the fractionation procedure, subcellular fractions were also analyzed with antibodies against markers of the lipid raft (Flotillin-1), plasma membrane (Na/K ATPase), and cytosol (ERK2) fractions. (B) Verification of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit in lipid rafts by IP. Because the data in A consist of an immunoblot that can only be used to infer that the approximately 160-kDa-phosphorylated band is Kit, an IP of lipid raft-localized Kit from resolubilized lysates was performed and analyzed with antibodies against Kit and PY. The coprecipitating, tyrosine-phosphorylated band of significantly higher molecular mass than Kit is of unknown origin. (C) Recruitment of p85 into lipid rafts, redistribution of the negative regulator PTEN from lipid rafts to the cytosol. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against the p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunits of PI3K, PTEN, Akt and PDK1. (D) Complex formation between Kit and p85 in lipid rafts and verification of tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. As in B, an IP of Kit and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins from lipid rafts was performed and analyzed with an antibody against p85.

, respectively. A protein of somewhat lower molecular mass cross-reacting with the anti-Kit antibody was observed in the cytosol and possibly represents a cytosolic Kit degradation product (⇨). For control of the fractionation procedure, subcellular fractions were also analyzed with antibodies against markers of the lipid raft (Flotillin-1), plasma membrane (Na/K ATPase), and cytosol (ERK2) fractions. (B) Verification of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit in lipid rafts by IP. Because the data in A consist of an immunoblot that can only be used to infer that the approximately 160-kDa-phosphorylated band is Kit, an IP of lipid raft-localized Kit from resolubilized lysates was performed and analyzed with antibodies against Kit and PY. The coprecipitating, tyrosine-phosphorylated band of significantly higher molecular mass than Kit is of unknown origin. (C) Recruitment of p85 into lipid rafts, redistribution of the negative regulator PTEN from lipid rafts to the cytosol. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against the p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunits of PI3K, PTEN, Akt and PDK1. (D) Complex formation between Kit and p85 in lipid rafts and verification of tyrosine phosphorylation of p85. As in B, an IP of Kit and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins from lipid rafts was performed and analyzed with an antibody against p85.

In an independent experiment, we verified by IP that the tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in lipid rafts was in fact Kit (Figure 1B). Proteins in the lipid raft fractions obtained at 0, 5, and 20 minutes of KL stimulation were resolubilized before IP of Kit (“Materials and methods, Immunoprecipitations and immunoblotting”). Taken together, our observations suggest that Kit is either initially activated in lipid rafts or rapidly translocates to the lipid rafts from the membrane after ligand engagement. In contrast, Kit protein located in the membrane is either nonphosphorylated (0 and 5 minutes) or phosphorylated Kit that probably had translocated from the lipid rafts after activation (20 minutes). Three marker proteins used to validate the presence and purity of the fractions obtained (Flotillin-1 as a marker of lipid rafts,28 Na/K-ATPase for both rafts and the plasma membrane, ERK2 for the cytosol) did not undergo any redistribution after KL stimulation (Figure 1A). The presence of a lipid raft fraction in unstimulated cells indicates that rafts in Mo7e cells are preformed and exist independently of KL stimulation.

Consistent with previous studies,18–20 the SFKs investigated (Hck, Lck, Fyn, and Lyn) were predominantly found in the lipid raft fraction in both unstimulated and KL-stimulated Mo7e cells (SOM; Figure S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Figures links at the top of the online article). SFKs were the most abundant tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in lipid rafts (SOM; Figure S2). In contrast to the constitutive localization of SFKs to lipid rafts, the non-SFK tyrosine kinase Syk was present in the membrane and cytosol in resting and stimulated cells, but was not found in lipid rafts (SOM; Figure S1). The initial appearance of Kit in the SFK-enriched environment of lipid rafts could be the topologic correlate for 2 paradoxical findings. On the one hand, there are observations that SFKs are downstream targets of Kit29–31 ; on the other hand, SFKs are reported to be involved in the initial activation of Kit by phosphorylating tyrosine residues within the Kit cytoplasmic tail that are not autophosphorylation sites.32 Hence, the lipid raft compartment may be the primary subcellular location for the interplay between RTKs and SFKs.33

The PI3-K regulatory subunit p85 is recruited to lipid rafts with kinetics similar to those of Kit

RTKs engage the class-Ia PI3-K, which is a heterodimer consisting of the p85 regulatory and p110 catalytic subunits.34 PI3-K activation by Kit requires direct Src homology 2 (SH2) domain-dependent binding of p85 at the phosphophorylated tyrosine at position 721 (Tyr721) of activated human Kit (Tyr719 of mouse Kit).35 The second messenger PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 (PIP3) is generated by the entire PI3-K complex consisting of p85 and p110. PIP3 and the derivative PtdIns(3,4)P2 bind with high affinity to the pleckstrin homology (PH) region of downstream proteins like the serine/threonine kinases PDK1 and Akt, leading to their activation.36 Activated PDK1 phosphorylates Akt at Thr308 in the activation loop.37 Complete activation of PDK1 requires additional phosphorylation of Ser473 within the carboxyl terminus, possibly mediated by PDK1 or a different kinase.38

Because of the observed recruitment of Kit to lipid rafts and the known direct association of p85 and Kit, we examined the subcellular localization of PI3-K and its downstream effectors after KL stimulation of Mo7e cells (Figure 1C). In unstimulated cells, the PI3-K regulatory subunit p85 was absent from lipid rafts but present in the membrane and cytosol. After 5 minutes of stimulation, p85 was recruited to lipid rafts. At 20 minutes, p85 levels were again reduced in lipid rafts but increased in the membrane and the cytosol. IP of Kit and tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins (Figure 1D) from the lipid raft fraction revealed that p85 is associated with Kit in lipid rafts as a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein. Thus, both Kit and associated p85 are rapidly and transiently recruited to the lipid raft fraction after KL stimulation. It has recently been shown that p110 is localized to caveolin-enriched microdomains (CEMs).39 Consistently, p110 was found to be present in the lipid raft fraction. In addition, p110 was constitutively present in the membrane and the cytosol (Figure 1). The differential localization of p85 and p110 in unstimulated cells and the Kit-mediated transfer of p85 to raft-localized p110 suggests that activation-dependent localization of the RTK Kit to lipid rafts controls the assembly of the PI3-K complex in lipid rafts.

PDK1 and Akt are recruited to the membrane after Kit activation

Analysis of the PI3-K downstream effectors PDK1 and Akt revealed that both kinases were restricted to the cytosol before Kit activation and appeared in the membrane at low levels after 20 minutes of KL stimulation (Figure 1C). Both kinases were absent from the lipid raft fraction. Thus, although PI3-K is activated in the lipid rafts, downstream targets like Akt or PDK1 are recruited to the nonraft membrane domain from the cytosol. The absence of PDK1 and Akt from the rafts suggests that the PI3-K-generated PIP3 molecules diffuse from either raft or membrane through the cytosol to bind their substrates. The data do not allow us to state whether such targets are initially activated in the membrane or cytosol.

PTEN levels in lipid rafts are reduced after KL stimulation

A different pattern of localization was observed for PTEN phosphatase (Figure 1C). PTEN negatively regulates the PI3-K/Akt signaling pathway by hydrolysis of inositol phospholipids generated by PI3-K.40 PTEN was recently reported to be targeted to lipid rafts.41 In unstimulated Mo7e cells, PTEN was present in the lipid raft fraction and cytosol in unstimulated Mo7e cells. Kit stimulation resulted in notable reduction of PTEN in lipid rafts. The reduction of PTEN levels in lipid rafts was paralleled by an increase of PTEN in the cytosol. PTEN in lipid rafts was present as a single electrophoretic band while cytosolic PTEN was detected as a doublet. These 2 forms might be a result of differential secondary protein modifications, that is, phophorylation on serine residues which PTEN is known for.42 Thus, the recruitment of p85 to lipid rafts is accompanied by a reduction of PTEN levels in lipid rafts. These observations suggest that PI3-K activation by Kit occurs via lipid raft–dependent converse regulation of positive and negative effectors of the PI3-K pathway.

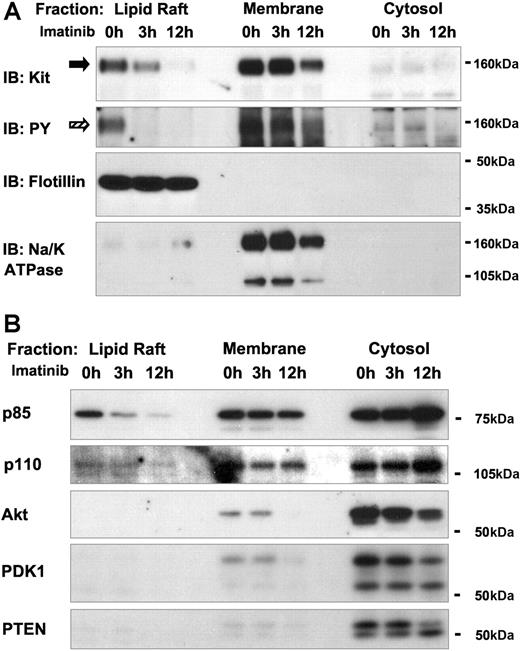

Localization of oncogenic Kit in lipid rafts requires kinase activity

The data from KL-mediated stimulation of wild-type Kit in Mo7e cells were consistent with the hypothesis that KL-mediated activation of Kit regulates PI3-K activation via spatiotemporal changes in protein distribution in lipid rafts. Because activated Kit can also be generated by oncogenic mutations in the absence of KL, the question of whether oncogenic Kit and its downstream mediators were also localized in lipid rafts was addressed. HMC-1 is a human mast-cell line derived from a patient with mast-cell leukemia.43 HMC-1 cells express the dimerizing oncogenic Kit mutant 560V>G (Kit560V>G), which is responsive to the Abl/Kit inhibitor imatinib (“Materials and methods, Cell culture and media”). As opposed to the ligand-mediated activation of wild-type Kit that was tested in Mo7e cells, the localization of Kit, PI3-K, and their substrates was examined in HMC-1 cells before and after inhibition of oncogenic Kit kinase for 3 or 12 hours by imatinib. In untreated HMC-1 cells, tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit was detected in the lipid raft and in the membrane fraction (Figure 2A). Imatinib treatment resulted in the progressive disappearance of Kit from the lipid raft fraction. The levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit decreased in the lipid raft fraction faster than total Kit protein. Eventually, imatinib treatment also led to decreased Kit in the membrane fraction (Figure 2A) and the appearance of a degradation product of Kit (∼50 kDa) in the membrane and cytosol (data not shown). Imatinib-sensitive oncogenic Kit in lipid rafts of HMC-1 cells corresponds to the KL-dependent recruitment of wild-type Kit to lipid rafts in Mo7e cells. Like in Mo7e cells, where tyrosine-phoshorylated Kit initially occurred in the lipid rafts, activation of oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells also seemed to initially occur in lipid rafts rather than in the membrane, for in imatinib-treated HMC-1 cells, tyrosine-phosphorylated Kit disappeared first from the lipid rafts before its level decreased in the membrane. Like Mo7e cells, lipid raft fractions could be isolated from HMC-1 cells, regardless of whether Kit was activated or inhibited by imatinib (Figure 2A), suggesting the existence of preformed lipid raft domains independent of the activation status of Kit.

Kinase-dependent localization of oncogenic Kit and PI3-K signaling molecules in lipid rafts. (A) Effect of imatinib treatment on the subcellular localization of oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells. Subcellular fractionation was performed as for Figure 1, using the HMC-1 cell line expressing the oncogenic Kit560V>G. Cells were incubated in imatinib containing media (1 μM) for 3 or 12 hours. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against Kit and PY. Kit and phosphorylated Kit proteins are indicated by  and

and  , r, respectively. For quality control of the fractions, lipid raft and membrane fractions were verified by IB for Flotillin-1 and Na/K ATPase. (B) Effect of imatinib treatment on the localization of p85 in lipid rafts of HMC-1 cells. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against p85, p110, PTEN, Akt, and PDK1.

, r, respectively. For quality control of the fractions, lipid raft and membrane fractions were verified by IB for Flotillin-1 and Na/K ATPase. (B) Effect of imatinib treatment on the localization of p85 in lipid rafts of HMC-1 cells. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against p85, p110, PTEN, Akt, and PDK1.

Kinase-dependent localization of oncogenic Kit and PI3-K signaling molecules in lipid rafts. (A) Effect of imatinib treatment on the subcellular localization of oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells. Subcellular fractionation was performed as for Figure 1, using the HMC-1 cell line expressing the oncogenic Kit560V>G. Cells were incubated in imatinib containing media (1 μM) for 3 or 12 hours. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against Kit and PY. Kit and phosphorylated Kit proteins are indicated by  and

and  , r, respectively. For quality control of the fractions, lipid raft and membrane fractions were verified by IB for Flotillin-1 and Na/K ATPase. (B) Effect of imatinib treatment on the localization of p85 in lipid rafts of HMC-1 cells. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against p85, p110, PTEN, Akt, and PDK1.

, r, respectively. For quality control of the fractions, lipid raft and membrane fractions were verified by IB for Flotillin-1 and Na/K ATPase. (B) Effect of imatinib treatment on the localization of p85 in lipid rafts of HMC-1 cells. Fractions were immunoblotted with antibodies against p85, p110, PTEN, Akt, and PDK1.

The SFKs Hck, Lck, Fyn, and Lyn that were expressed in Mo7e cells were also found to be expressed in HMC-1 cells and were predominantly localized in the lipid raft fraction (SOM; Figure S3). Analysis of the total phosphorylated proteins in lipid raft, membrane, and cytosol fraction revealed that the SFKs were constitutively tyrosine-phosphorylated and that these proteins were by far the predominant tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in untreated and imatinib-treated HMC-1 cells (SOM; Figure S4). Imatinib treatment caused reduction of tyrosine phosphorylation and decreased levels of SFKs in the lipid raft fraction by 12 hours, whereas levels of Lck, Fyn, and Lyn increased eventually in the cytosol (SOM; Figure S3). Interestingly, cytosolic levels of tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins also increased at 12 hours of imatinib treatment (SOM; Figure S4). We hypothesize that the localization SFKs to lipid rafts in HMC-1 depends in part on the activation state of the oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells and that imatinib-induced inhibition of Kit kinase-activity in HMC-1 cells could be the underlying reason for the redistribution of SFKs from lipid rafts and the membrane to the cytosol. Whether localization of SFKs to the cytosol could account for the observed increase in cytosolic phospho-proteins remains under investigation.

p85 localization in lipid rafts depends on oncogenic Kit tyrosine kinase activity

Both oncogenic dimerization and catalytic mutants of Kit have been demonstrated to lead to constitutive activation of PI3-K or Akt. Abolishment of Kit-induced activation of PI3-K by mutation of Tyr719 to Phe (Tyr719Phe) in murine Kit leads to loss of Akt activation and significant decreases of growth and tumorigenicity of cells expressing the kit kinase-domain mutant.44 Thus, the interactions of Kit with p85 are critical for signaling downstream of both wild-type and oncogenic Kit. We analyzed the distribution of p85, p110, PDK1, Akt, and PTEN in HMC-1 cells (Figure 2B). In untreated cells, p85 was present in the lipid raft, membrane, and cytosol fractions. Kit inhibition by imatinib led to progressively reduced levels of p85 in the lipid raft and membrane fraction and to an increase of p85 in the cytosol (Figure 2B). Similar to the Mo7e cells, p110 was found in lipid rafts and in the membrane and the cytosol, and its distribution did not change considerably after imatinib treatment of HMC-1 cells (Figure 2B). The apparent redistribution of p85 from lipid rafts and the membrane to the cytosol as a result of imatinib-induced inhibition of Kit kinase activity is likely to be the converse of the KL-dependent recruitment of p85 to lipid rafts in Mo7e cells.

In the presence of oncogenic Kit, PDK1 and Akt are localized to the membrane and cytosol while PTEN is cytosolic

Akt and PDK were constitutively present in the cytosol of untreated HMC-1 cells with small amounts also being present in the membrane (Figure 2B). After 3 hours of imatinib treatment of the HMC-1 cells, there was no apparent redistribution of PDK1 or Akt. However, after 12 hours, Akt and PDK1 levels in the cytosol and membrane were reduced. As previously seen with the Mo7e cells, Akt and PDK1 were not detected in the lipid raft fraction of HMC-1 cells. PTEN was predominantly localized to the cytosol in untreated cells with only trace amounts detected in the membrane (Figure 2B). Based on the presence of PTEN in the rafts of unstimulated Mo7e cells, one might predict that imatinib treatment of HMC-1 would lead to redistribution of PTEN to the rafts. However, exposure of HMC-1 cells to imatinib did not change the overall distribution of PTEN. Thus, with the exception of PTEN, the effect of imatinib on the distribution of molecules in the PI3-K pathway (p85, Akt, and PDK1) in HMC-1 cells was the converse of KL-induced redistribution of these proteins in Mo7e cells.

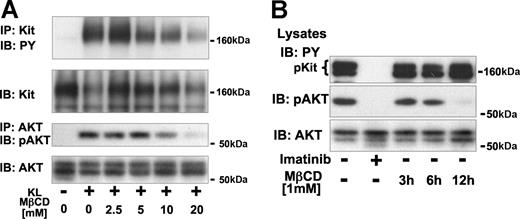

Activation of Akt by wild-type and oncogenic Kit requires lipid rafts

Both KL-dependent Kit activation and PI3-K signaling in Mo7e cells and imatinib-induced blockade of oncogenic Kit activity involved spatiotemporal changes in lipid raft and membrane distribution. To investigate the implications of localization in lipid rafts for downstream signaling of wild-type and oncogenic Kit, we analyzed the effects of lipid raft disruption on activation of Kit and the PI3-K effector Akt. As mentioned above, formation of lipid rafts can be inhibited by treatment of cells with MβCD by the depletion of cholesterol.22,45 Preincubation of Mo7e cells for 15 minutes in media containing MβCD resulted in a concentration-dependent decrease of KL-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Kit and of Kit-dependent activation of Akt (Figure 3A). Incubation of HMC-1 cells in media containing MβCD resulted in a time-dependent decrease of Akt phosphorylation (Figure 3B). After 12 hours of MβCD treatment, Akt activation was almost completely blocked. Thus activation of Akt mediated by wild-type Kit in Mo7e cells and by oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells is MβCD-sensitive. We hypothesize that Akt activation mediated by Kit depends on the integrity of the lipid rafts.

Activation of Akt by wild-type and oncogenic Kit depends on lipid rafts. (A) Effect of lipid rafts disruption on KL-mediated activation of Kit and Akt. Kit and Akt were immunoprecipitated from Mo7e cells that had been preincubated for 20 minutes in media containing the indicated concentration of MβCD and then stimulated with KL for 5 minutes. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for tyrosine phosphorylation of Kit and phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473. Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated protein were verified by IB the same blots with antibodies against Kit and Akt. (B) Effect of lipid raft disruption on activation of Akt by oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells. Lysates from HMC-1 cells incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM imatinib for 3 hours or in the presence of 1 mM MβCD for 3, 6, or 12 hours were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with antibodies against phosphotyrosine, phosphorylated Akt (Ser473), and Akt.

Activation of Akt by wild-type and oncogenic Kit depends on lipid rafts. (A) Effect of lipid rafts disruption on KL-mediated activation of Kit and Akt. Kit and Akt were immunoprecipitated from Mo7e cells that had been preincubated for 20 minutes in media containing the indicated concentration of MβCD and then stimulated with KL for 5 minutes. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed for tyrosine phosphorylation of Kit and phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473. Equal amounts of immunoprecipitated protein were verified by IB the same blots with antibodies against Kit and Akt. (B) Effect of lipid raft disruption on activation of Akt by oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells. Lysates from HMC-1 cells incubated in the absence or presence of 1 μM imatinib for 3 hours or in the presence of 1 mM MβCD for 3, 6, or 12 hours were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with antibodies against phosphotyrosine, phosphorylated Akt (Ser473), and Akt.

Interestingly, tyrosine phosphorylation of the oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells (Figure 3B) was not reduced by MβCD treatment, even after 12 hours of MβCD exposure. This result is different from the effects of imatinib, which inhibited both Kit tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of Akt by 3 hours of incubation. The differential effects of MβCD on Kit phosphorylation and downstream signaling suggest that raft disruption did not directly prevent Kit dimerization or activation. Rather, events downstream of Kit activation were blocked by disruption of the lipid rafts.

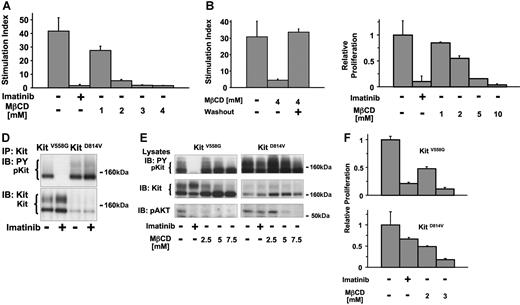

Lipid rafts are required for proliferation induced by wild-type and oncogenic Kit

To determine the biologic significance of lipid rafts in Kit-dependent survival and proliferation, we examined proliferation of wild-type Kit in Mo7e cells and oncogenic Kit in HMC-1 cells in the absence or presence of MβCD or imatinib as a positive control. Culture of Mo7e cells in the presence of imatinib (1 μM) reduced the proliferative response as measured by thymidine-incorporation to less than 5% of untreated cells (Figure 4A). Culture of the cells in the presence of MβCD reduced KL-induced proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 4A). At concentrations of 3 mM MβCD or greater, inhibition was equivalent to that of imatinib treatment. Nonspecific cell death induced by MβCD in the absence of growth factors was tested by long-term incubation of Mo7e cells either in media alone or media containing MβCD at a concentration of 2 or 4 mM. No significant differences in the numbers of viable cells were observed (SOM; Figure S5). To test the reversibility of the antiproliferative effect of MβCD, experiments were performed in which cells were exposed to MβCD as in Figure 4A, but then MβCD was washed from the medium and KL-induced proliferation was determined by thymidine incorporation. At concentrations of MβCD below 10 mM, such as 4 mM (Figure 4B), KL-mediated proliferation could be restored after MβCD washout.

Lipid rafts are required for proliferation induced by wild-type and oncogenic Kit. (A) Effect of MβCD on KL-mediated proliferation of Mo7e cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation over a time period of 12 hours of Mo7e cells stimulated with KL for 24 hours in the absence or in the presence of imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD at the indicated concentrations was determined. The stimulation index was measured as the ratio of incorporated radioactivity by KL-stimulated cells and unstimulated cells, measured in triplicate (all values ± 1 SD). (B) Reversibility of the growth inhibitory effect of MβCD on Mo7e cells. To rule out irreversible toxic effects of MβCD, a washout experiment was performed for the incubation of cells in the presence of 4 mM MβCD, the highest concentration used in A. The stimulation index was determined using Mo7e cells incubated in either the absence or presence of 4 mM MβCD. After 24 hours, cells were washed and resuspended in fresh media with or without MβCD for 6 hours before 3H-thymidine incorporation in the presence or absence of KL for 12 hours. (C) Effect of MβCD on the proliferation of HMC-1 cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation over a time period of 12 hours was analyzed after incubation of the cells in media alone or in the presence of either imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD for 24 hours at the indicated concentrations. Relative proliferation refers to the ratio of incorporated radioactivity by cells at their respective media conditions and untreated cells. (D) Comparison of the effect of imatinib on murine Kit558V>G and Kit814D>V expressed in Ba/F3 cells. Cells were incubated for 12 hours in either media alone or media containing 1 μM imatinib. Immunoprecipitated Kit protein was analyzed for tyrosine phosphorylation (top) and the presence of Kit protein (bottom). (E) Analysis of the effects of imatinib and MβCD on Akt activation mediated by Kit558V>G or Kit814D>V. Lysates from Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 KitD814V cells incubated for 6 hours in media alone or in the presence of 1 μM imatinib or MβCD at the concentrations indicated were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with antibodies against phosphotyrosine, Kit, and phosphorylated Akt (Ser473). (F) Growth inhibitory effect of MβCD on Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 Kit814D>V cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation of Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 Kit814D>V cells was analyzed in the absence or in the presence of imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD at the indicated concentrations. Relative proliferation refers to the ratio of 3H-thymidine incorporation of cells in their respective media conditions and in media alone.

Lipid rafts are required for proliferation induced by wild-type and oncogenic Kit. (A) Effect of MβCD on KL-mediated proliferation of Mo7e cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation over a time period of 12 hours of Mo7e cells stimulated with KL for 24 hours in the absence or in the presence of imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD at the indicated concentrations was determined. The stimulation index was measured as the ratio of incorporated radioactivity by KL-stimulated cells and unstimulated cells, measured in triplicate (all values ± 1 SD). (B) Reversibility of the growth inhibitory effect of MβCD on Mo7e cells. To rule out irreversible toxic effects of MβCD, a washout experiment was performed for the incubation of cells in the presence of 4 mM MβCD, the highest concentration used in A. The stimulation index was determined using Mo7e cells incubated in either the absence or presence of 4 mM MβCD. After 24 hours, cells were washed and resuspended in fresh media with or without MβCD for 6 hours before 3H-thymidine incorporation in the presence or absence of KL for 12 hours. (C) Effect of MβCD on the proliferation of HMC-1 cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation over a time period of 12 hours was analyzed after incubation of the cells in media alone or in the presence of either imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD for 24 hours at the indicated concentrations. Relative proliferation refers to the ratio of incorporated radioactivity by cells at their respective media conditions and untreated cells. (D) Comparison of the effect of imatinib on murine Kit558V>G and Kit814D>V expressed in Ba/F3 cells. Cells were incubated for 12 hours in either media alone or media containing 1 μM imatinib. Immunoprecipitated Kit protein was analyzed for tyrosine phosphorylation (top) and the presence of Kit protein (bottom). (E) Analysis of the effects of imatinib and MβCD on Akt activation mediated by Kit558V>G or Kit814D>V. Lysates from Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 KitD814V cells incubated for 6 hours in media alone or in the presence of 1 μM imatinib or MβCD at the concentrations indicated were separated by SDS/PAGE and analyzed with antibodies against phosphotyrosine, Kit, and phosphorylated Akt (Ser473). (F) Growth inhibitory effect of MβCD on Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 Kit814D>V cells. 3H-thymidine incorporation of Ba/F3 Kit558V>G or Ba/F3 Kit814D>V cells was analyzed in the absence or in the presence of imatinib (1 μM) or MβCD at the indicated concentrations. Relative proliferation refers to the ratio of 3H-thymidine incorporation of cells in their respective media conditions and in media alone.

To test whether proliferation of cells expressing oncogenic Kit also depended on the integrity of the lipid rafts, HMC-1 cells were treated with various concentrations of MβCD or imatinib as a control (Figure 4C). Imatinib treatment inhibited proliferation to approximately 10% of that of untreated HMC-1 cells. Similar to the results seen with the Mo7e cells, MβCD treatment was also inhibitory of HMC-1 cells in a dose-dependent manner. However, the MβCD dose required for maximal inhibition was ≥5 mM. Unlike the Mo7e cells, growth of HMC-1 cells could not be restored after washout of either imatinib or MβCD (data not shown).

The imatinib-resistant oncogenic mutant Kit814D>V is sensitive to lipid raft inhibition

To investigate the role of lipid rafts in different types of Kit mutations, we established Ba/F3 cells stably expressing either the KitV558G dimerizing mutant or the KitD814V catalytic mutant. Ba/F3 cells are a murine B lymphoid cell line that has been extensively used to study signaling through cytokine receptors. Expression of either Kit mutant resulted in factor-independent growth of the transfected Ba/F3 cells (Figure 4F). Consistent with the differential sensitivity of KitV558G and KitD814V to imatinib (Figure 4D), Akt inhibition was observed in Ba/F3-KitV558G cells treated with imatinib, but not in the imatinib-resistant Ba/F3-KitD814V cells (Figure 4E). In contrast, culture of the cells in the presence of MβCD resulted in a reduction of Akt phosphorylartion in both Ba/F3-KitV558G and Ba/F3-KitD814V cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4E). The MβCD concentration necessary to inhibit Akt phosphorylation in Ba/F3-KitD814V cells was somewhat higher than in Ba/F3-KitV558G. As with HMC-1 cells, tyrosine phosphorylation of both Kit mutants was not significantly inhibited by MβCD treatment, indicating the dissociation of oncogenic Kit kinase activity/autophosphorylation from the activation of downstream targets like Akt in absence of functional rafts.

To determine whether lipid raft disruption could abrogate proliferation induced by both imatinib-sensitive and imatinib-resistant oncogenic Kit mutants, the effects of imatinib and MβCD on the proliferation of Ba/F3-KitV558G and Ba/F3-KitD814V cells was compared (Figure 4F). As expected from the differential effects of imatinib on the activation of Akt, there was significant inhibition of proliferation of Ba/F3-KitV558G cells by imatinib, but only mild inhibition of Ba/F3-KitD814V cells. In contrast, lipid raft disruption by MβCD inhibited proliferation of both the imatinib-sensitive Ba/F3-KitV558G and the imatinib-resistant Ba/F3-KitD814V cells. Thus, the proliferation mediated by wild-type and 2 different oncogenic forms of Kit is MβCD-sensitive. Together with the inhibitory effect of MβCD on activation of Akt via wild-type and oncogenic Kit, our data suggest that Kit-mediated proliferative signals through the PI3-K/Akt signaling pathway depend on lipid rafts.

Discussion

Model of spatiotemporal regulation of Kit activation and Kit-dependent activation of PI3-K

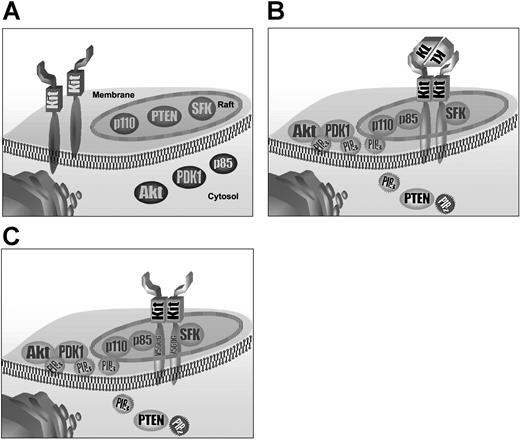

Our data on regulation of kit signaling through lipid raft are summarized in form of a cartoon (Figure 5). In unstimulated cells, the partition of Kit and p85 in the membrane and SFKs and p110 in the rafts may ensure that Kit and PI3-K interactions do not occur in a ligand-independent manner (Figure 5A). Once receptor engagement by ligand has occurred, Kit recruitment to the lipid rafts allows interaction with the SFKs. This is probably important for the initial activation of Kit where SFKs could phosphorylate nonautophosphorylation sites in the Kit cytoplasmic tail, which are essential for Kit signaling (Figure 5B).14,32 The recruitment of p85 from the cytoplasm to the raft is likely to have 2 mechanistic effects: (1) high density of activated Kit and p85 increases the phosphorylation of p85 by Kit, and (2) the association of p85 with p110, which is constitutively present in the raft, is probably also facilitated by their colocalization within rafts. In contrast, PDK1, Akt and PH-domain-containing adaptor molecules were not localized in the rafts. Therefore, the main effector location for PIP3, the product of PI3-K activity, seems to be the membrane and the cytosol rather than lipid rafts. The localization of PH-domain proteins is consistent with their activation occurring after diffusion of PIP3 generated by PI3-K. The partitioning of the signaling molecules also applies to negative regulatory pathways. The movement of the negative regulatory phosphatase PTEN from the rafts to the cytoplasm increases its proximity to its cytosolic PIP3 substrate and might represent a negative feedback loop to limit the cytosolic concentration of free PIP3.

Model of spatiotemporal regulation of Kit activation and Kit-dependent activation of PI3-K. (A) In unstimulated cells, Kit is present in the plasma membrane. Lipid rafts contain SFKs, PTEN, and p110. Before stimulation, p85, PDK1, and Akt are located in the cytosol. Upon KL stimulation wild-type Kit is recruited to lipid rafts, leading to interaction with SFKs. Association of Kit with p85 leads to assembly of the PI3-K complex. Diffusion of PI-3K-generated PIP3 to the cytosol and binding to PDK1 and Akt via PH domains results in translocation of PDK1 and Akt to the plasma membrane, where they become activated. Activation of Akt mediates Kit-dependent proliferation. PTEN translocates from lipid rafts to the cytosol where it deactivates cytosolic PIP3. (C) Oncogenic Kit is initially located in lipid rafts in a tyrosine kinase-dependent manner. Some Kit protein is also present in the membrane (not shown). Association of oncogenic Kit with p85 in lipid rafts leads to constitutive activation of PI3-K and Akt. PTEN is located primarily in the cytosol.

Model of spatiotemporal regulation of Kit activation and Kit-dependent activation of PI3-K. (A) In unstimulated cells, Kit is present in the plasma membrane. Lipid rafts contain SFKs, PTEN, and p110. Before stimulation, p85, PDK1, and Akt are located in the cytosol. Upon KL stimulation wild-type Kit is recruited to lipid rafts, leading to interaction with SFKs. Association of Kit with p85 leads to assembly of the PI3-K complex. Diffusion of PI-3K-generated PIP3 to the cytosol and binding to PDK1 and Akt via PH domains results in translocation of PDK1 and Akt to the plasma membrane, where they become activated. Activation of Akt mediates Kit-dependent proliferation. PTEN translocates from lipid rafts to the cytosol where it deactivates cytosolic PIP3. (C) Oncogenic Kit is initially located in lipid rafts in a tyrosine kinase-dependent manner. Some Kit protein is also present in the membrane (not shown). Association of oncogenic Kit with p85 in lipid rafts leads to constitutive activation of PI3-K and Akt. PTEN is located primarily in the cytosol.

Mechanism of raft recruitment

The mechanisms for the observed spatiotemporal dynamics depend on the activation state of Kit itself and reveal reciprocal events: Activation of Kit tyrosine kinase is required for raft recruitment, but then raft recruitment is required for Kit signaling, The dependence of Kit receptor signaling on recruitment to lipid rafts is similar to results seen after stimulation through the multivalent immunoreceptors, TCR, BCR, and FcϵRI. In T cells, the localization of TCR molecules in rafts is dynamic, with the TCR subunits described as not being present in lipid rafts before engagement with ligand but being found in rafts after 5 min of stimulation.18 Ligand engagement is essential for the redistribution of the TCR subunits to the rafts. Redistribution of wild-type Kit also depended on ligand engagement. In HMC-1 cells that were cultured in the babsence or presence of the kinase inhibitor imatinib, the changes in protein distribution were largely the converse of those after ligand engagement of wild-type Kit in Mo7e cells (Figure 5C). Although imatinib is not a Kit-specific inhibitor, the similarities between unstimulated Mo7e cells and imatinib-treated HMC-1 cells, on the one hand, and KL-stimulated Mo7e cells and untreated HMC-1 cells are striking. In the HMC-1 cells, imatinib inhibition of constitutive Kit activity resulted in the progressive disappearance of Kit and the p85 and p110 subunits of PI3-K from the lipid rafts. Interestingly, the constitutive phosphorylation of raft-localized SFKs also depended on Kit activation. The mechanisms for redistribution of the signaling molecules after Kit activation are unknown. While MβCD directly affects lipid distribution in the membrane, raft recruitment after the activation of Kit probably requires involvement of the cytoskeleton. Recently, protein–protein interactions have been shown to be necessary for movement of downstream mediators of the TCR,46 and it is unlikely that the observed spatiotemporal dynamics for Kit can be mediated by changes in the membrane lipids alone. As for TCR signaling, actin reorganization has been described after Kit activation.47 The mechanisms by which Kit interacts with actin and other cytoskeletal proteins are likely to be fruitful in understanding the basis for the spatiotemporal changes in RTK distribution.

Lipid raft recruitment as a novel strategy to target RTKs?

Unlike the Mo7e cells, growth of HMC-1 cells could not be restored after washout of either imatinib or MβCD (data not shown). The difference in dependence on either Kit activity or raft integrity of the Mo7e cells expressing wild-type Kit and the HMC-1 cells expressing mutated Kit is reminiscent of the term “oncogene addiction” describing the sole dependence of a transformed cell on the acting oncogene.48 For example, lung tumor cells expressing constitutively active epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs) appear to be more sensitive to the kinase-inhibitor gefitinib than those expressing wild-type EGFRs.49 The same observation was made for oncogenic Kit.50 The fact that imatinib has relatively few side effects while it probably inhibits many other kinases potently than the ones we currently know (ie, Abl, Kit, or PDGFR) seems to validate the speculation that potential drugs that interfere more or less specifically with the recruitment process of an RTK could be tolerable at least for a while for a normal cell but might initiate irreversible apoptosis in the tumor cells. Furthermore, targeting the lipid raft localization of an RTK would be an extremely attractive strategy because it addresses the general activation mechanism of RTKs rather than the specific mutant of one RTK, for the same reason it may be less vulnerable to the development of secondary resistance mechanisms that have limited the success of other targeted therapies.

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Pilot and Feasibility Fellowship of the Saban Research Institute of Childrens Hospital Los Angeles (to T.J.), grants from the Wright Foundation (to T.J.), and National Institutes of Health Grants AI50765 and HL54729 (to K.W.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: T.J. designed experiments, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; E.L. performed experiments and analyzed data; S.G. performed experiments and analyzed data; S.S. performed experiments; K.W. designed experiments and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Thomas Jahn, Division of Stem Cell Transplantation, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford School of Medicine, 300 Pasteur Drive, Stanford, CA 94305-5208; e-mail: tjahn@stanford.edu.