Abstract

Junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) is a transmembrane protein expressed at tight junctions of endothelial and epithelial cells and on the surface of platelets and leukocytes. The role of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo was directly investigated by intravital microscopy using both a JAM-A–neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) (BV-11) and JAM-A–deficient (knockout [KO]) mice. Leukocyte transmigration (but not adhesion) through mouse cremasteric venules as stimulated by interleukin 1β (IL-1β) or ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury was significantly reduced in wild-type mice treated with BV-11 and in JAM-A KO animals. In contrast, JAM-A blockade/genetic deletion had no effect on responses elicited by leukotriene B4 (LTB4) or platelet-activating factor (PAF). Furthermore, using a leukocyte transfer method and mice deficient in endothelial-cell JAM-A, evidence was obtained for the involvement of endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration mediated by IL-1β. Investigation of the functional relationship between JAM-A and PECAM-1 (CD31) determined that dual blockade/deletion of these proteins does not lead to an inhibitory effect greater than that seen with blockade/deletion of either molecule alone. The latter appeared to be due to the fact that JAM-A and PECAM-1 can act sequentially to mediate leukocyte migration through venular walls in vivo.

Introduction

Leukocyte migration across vessel walls and into the surrounding tissue is a characteristic feature of an inflammatory response in physiologic host defense and also under pathologic scenarios in inflammatory disease states such as myocardial infarction. This process is known to occur via a number of sequential leukocyte responses beginning with the tethering to and rolling of leukocytes on the vascular endothelium.1 After stimulation by surface-bound activating molecules such as chemokines, rolling leukocytes can then establish a firm adhesive interaction with endothelial cells and finally begin to migrate through the endothelial-cell component of the vessel wall. This latter stage is believed to occur largely through junctions between adjacent endothelial cells; indeed, numerous endothelial-cell junctional molecules have now been implicated in this process.2 Such molecules include PECAM-1 (CD31), ICAM-2 (CD102), CD99, and members of the junctional adhesion molecule (JAM) family,3 although there remain many unanswered questions regarding their mode of action and potential additive/cooperative interactions.

JAMs are a family of transmembrane IgG glycoproteins expressed on a number of cell types throughout the vascular system. There are currently 5 known members of the family: JAM-A, JAM-B, JAM-C, JAM4, and JAML.4–6 JAM-A is the most widely expressed member of the family, and has been shown to be expressed on endothelial and epithelial cells, on platelets, and on a number of leukocyte subsets.2 In endothelial and epithelial cells, JAM-A locates to the tight junctions, where it appears to engage in homophilic binding to JAM-A on adjacent cells, an interaction that in endothelial cells is considered to play a critical role in angiogenesis.2,7 The integrin LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) has also been reported to act as a ligand for JAM-A, an interaction that has been implicated in leukocyte transendothelial cell migration,8 though the role of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo requires further clarification.

The involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration was first reported by Dejana and colleagues using the neutralizing antibody BV-11.5 Specifically, BV-11 was found to inhibit spontaneous and chemokine-induced monocyte transmigration through cultured endothelial cells, and chemokine-induced monocyte migration into murine subcutaneous air pouches.5 BV-11 was also found to suppress leukocyte recruitment to cerebrospinal fluid following cytokine-induced meningitis.9 Despite these positive effects of JAM-A blockade, other studies reported on the inability of anti–JAM-A antibodies to inhibit leukocyte transmigration. Hence, Shaw et al10 found that leukocyte transmigration through cultured endothelial cells under flow was not inhibited by another anti–JAM-A antibody, whereas under the same conditions, blockade of PECAM-1 did reduce transmigration. In addition, in vivo, BV-11 failed to inhibit leukocyte influx into the meninges following bacterial or viral murine meningitis.11 More recently, following the generation of JAM-A–deficient mice, further evidence has been obtained for the involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte infiltration and leukocyte-mediated tissue damage in murine models of ischemia-reperfusion injury and peritonitis.12,13 The aim of the present study was to extend these findings by directly investigating the role of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration, as observed by intravital microscopy, using both monoclonal antibody (mAb) BV-11– and JAM-A–deficient mice. In addition, as we have previously found that PECAM-1 and ICAM-2 mediate leukocyte transmigration in a stimulus-specific manner,14–16 we sought to investigate this possibility in the context of JAM-A. The relative functional roles of leukocyte and endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration were also investigated by the use of a cell-transfer method and mice deficient in endothelial-cell JAM-A. Finally, as many overlapping properties exist in terms of structure, expression profile, and function between JAM-A and PECAM-1,17 the study investigated the contribution of these proteins and compared their functional roles in the process of leukocyte transmigration. Collectively, the present study provides direct evidence for the involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte migration through venular walls, though this effect is stimulus-dependent. Furthermore, in the models used, JAM-A–mediated leukocyte transmigration is largely mediated via endothelial-cell JAM-A, and JAM-A and PECAM-1 appear to mediate migration of leukocytes through venular walls at distinct but sequential steps in the transmigration process.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male (20–25 g) C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice (Harlan-Olac, Bicester, United Kingdom); JAM-A–deficient (JAM-A−/−), PECAM-1–deficient (PECAM-1−/−), and endothelial-specific JAM-A–deficient (eJAM-A−/−) mice; and JAM-A−/−/PECAM−/− double knockout (KO) mice were used in this study. The JAM-A−/− and eJAM−/− mice were generated as previously described.13,18 PECAM-1−/− mice were obtained as gift from Dr Tak Mak (Amgen Institute, Toronto, ON).19 The JAM-A−/−/PECAM-1−/− (double KO) mice were generated by crossing the JAM-A−/− mice with PECAM-1−/− mice. WT, eJAM−/− and JAM-A−/−/PECAM-1−/− double KO mice were housed at Imperial College London (United Kingdom) and experiments were carried out under United Kingdom legislation. WT and JAM-A−/− mice were housed at Ludwig-Maximilians-University (Munich, Germany) and experiments were carried out under German legislation.

Reagents

Recombinant murine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was from R&D Systems (Abingdon, United Kingdom), calcein-AM was purchased from Molecular Probes (Poortgebouw, the Netherlands), leukotriene B4 (LTB4) was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), platelet-activating factor (PAF) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany), control IgG2b and IgG2a antibodies were from Serotec (Oxford, United Kingdom), and the anti–PECAM-1 mAb Mec13.3 was from Becton Dickinson (Cowley, United Kingdom). ICAM-2 mAb 3C4 was from BD Pharmingen (Cowley, United Kingdom). All other purchased reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany, or Poole, United Kingdom). The blocking anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11 was generated as previously reported.5,20

Intravital microscopy

Intravital microscopy (IVM) was used to directly observe leukocyte responses within mouse cremasteric venules as previously detailed.15,21 Mice were anesthetized using ketamine and xylazine, and the cremaster muscle was surgically exteriorized onto a purpose-built microscope stage and continuously superfused with warm Tyrode solution.15,21 Leukocyte responses were observed in postcapillary venules of 20 to 40 μm in diameter using an upright microscope (Carl Zeiss, Welwyn Garden City, United Kingdom, or Olympus Microscopy, Hamburg, Germany) fitted with water immersion objectives. Firmly adherent leukocytes were defined as those that remained stationary for more than 30 seconds over an area of 104 μm2 of the endothelial surface of the lumen. Leukocyte transmigration was quantified as the number of leukocytes that had migrated into the extravascular tissue within 50 μm on either side of a 100-μm-long vessel segment, an area of 104 μm2. Leukocyte transmigration was induced by topical application of fast-acting stimuli, leukotriene B4 (LTB4), or platelet-activating factor (PAF). These stimuli were continuously applied to the exteriorized cremaster muscles (10−7 M solution) for a period of 1 hour (LTB4) or 2 hours (PAF), during which leukocyte responses were quantified in 2 to 3 venules per animal at 20, 40, and 60 minutes after induction of inflammation. In control mice, cremaster muscles were superfused with Tyrode solution. Or mice were injected with intrascrotal saline (400 μL; control group) or IL-1β (50 ng/400 μL) 4 hours before exteriorization of the cremaster muscle and quantification of leukocyte responses in 3 to 5 venules. (3) I/R injury was induced in the cremaster muscle by induction of ischemia (30 minutes) through placement of an artery clamp at the base of the muscle, followed by its removal to initiate vascular reflow. Leukocyte responses were quantified in 2 to 3 venules at baseline conditions as well as at 30-minute intervals for 2 hours after initiation of reperfusion. In some experimental groups, mice were pretreated with intravenous saline, an isotype control mAb (IgG2b or IgG2a), the blocking anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11, or the blocking anti–PECAM-1 mAb Mec13.3 (all mAbs were administered at 3 mg/kg) 15 minutes before the induction of inflammatory reactions. In selected experiments, mean arterial blood pressure, blood flow velocity, and peripheral leukocyte counts were measured, largely as previously detailed,15,21 and no significant differences in these parameters were noted between the different strains of mice studied or in mice treated with different mAbs (data not shown).

Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses

To enable us to investigate the contribution of leukocyte and endothelial JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration and to assess the potential additive roles of JAM-A– and PECAM-1–dependent pathways, a cell-transfer technique was developed for observing the behavior of leukocytes from WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− donor mice when the cells were injected into WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− recipients. For this purpose, bone marrow leukocytes were isolated from donor mice by flushing the femur and tibia bones with PBS. Cells were then sieved and counted, resuspended in PBS containing BSA (0.25%), and incubated with calcein-AM (10 μM final concentration at 37°C for 30 minutes). After 2 washes, the cells were injected intravenously into recipient mice via the tail vein (107 cells/mouse) immediately prior to an intrascrotal injection of saline or IL-1β (50 ng). At 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized as detailed and observed using a fluorescent microscope incorporating a 485-nm and 515- to 540-nm excitation and emission filters, respectively. The results are shown as the number of adherent or transmigrated calcein-labeled cells/38 mm2 of tissue area, this being equivalent to the total quantifiable area of an exteriorized cremaster muscle in the present studies.

Immunofluorescence labeling and analysis of cremaster muscle tissues by confocal microscopy

To observe the expression patterns of JAM-A and PECAM-1, tissues were immunostained following intravenous and topical application of anti–JAM-A and anti–PECAM-1 mAbs, respectively. Briefly, animals were given an intravenous injection of 2 mg/kg rat antimouse BV-11 (anti–JAM-A) or IgG2b (control mAb); 10 minutes later, the animals were killed using a CO2 chamber. As the purpose of these experiments was to investigate the expression profile of molecules on endothelial cells, the mice were initially subjected to intravascular washout to remove platelets and leukocytes (which express JAM-A and PECAM-1). The cremaster muscles were then dissected away from the animals and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Tissues were blocked and permeabilized in PBS containing 20% normal goat serum and 0.5% Triton X-100, then incubated with a goat antirat Alexa-Fluor 488–conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). After washes, the tissues were incubated with a directly allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated rat antimouse mAb Mec13.3 against PECAM-1 (BD Biosciences, Oxford, United Kingdom). Samples were viewed using a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss) equipped with argon and helium-neon lasers incorporating a 40× objective lens (0.75 aperture water immersion). Acquired Z-stack images were used for three-dimensional reconstruction analysis of whole vessels using the LSM 5 Pascal software (version 3.2; Zeiss). For clarity, the image of JAM-A and PECAM-1 vascular expression shown in Figure 5A is the negative of the original, thus enabling expressions of the molecules to be shown in black on a white background.

The position of leukocytes in inflamed cremaster muscle tissues was quantified as previously detailed.22 Briefly, tissues from WT, JAM-A−/−, and PECAM-1−/− mice were fixed and blocked/permeabilized as described. The tissues were then immunostained with a marker for neutrophils (rat antimouse MRP-14, a gift from Dr Nancy Hogg, Cancer Research UK, London, United Kingdom23 ) and for the endothelial cell basement membrane (rabbit antimouse collagen IV; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) in PBS plus 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). After washes, tissues were subsequently incubated with specific 488-conjugated antirat and 555-conjugated antirabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Paisley, United Kingdom) for 4 hours at room temperature (RT) in PBS plus 10% FCS. To stain for endothelial cells, tissues were blocked with rat IgGs for 2 hours before being incubated with the rat antimouse APC-conjugated PECAM-1 antibody (for WT and JAM-A−/− mice) or the anti–ICAM-2 mAb 3C4 (for PECAM-1−/− mice) followed by a 633-conjugated antirat secondary antibody (Invitrogen). Three dimensional images of 150-μm lengths of venules (4 vessels per tissue) were acquired by confocal microscopy and analyzed using the image processing software Volocity version 6.0 (Improvision, Coventry, United Kingdom). This software enables analysis of acquired and reconstructed 3D images at different angles, thus allowing the position of leukocytes relative to the endothelium and the endothelial cell basement membrane to be determined accurately.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed using the statistical software SigmaStat for Windows (Jandel Scientific, Erkrath, Germany) or GraphPad Prism 4 (San Diego, CA). All results are expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. Where 2 variables were analyzed, a rank-sum test was used. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

JAM-A mediates leukocyte transmigration in a stimulus-specific manner

To directly investigate the role of JAM-A in the multistep process of leukocyte emigration in vivo, the effect of antibody blockade or genetic deletion of JAM-A on leukocyte responses within mouse cremasteric venules was observed by IVM. Furthermore, to address the potential stimulus-specific role of JAM-A in leukocyte migration, the effect of a number of inflammatory stimuli was investigated.

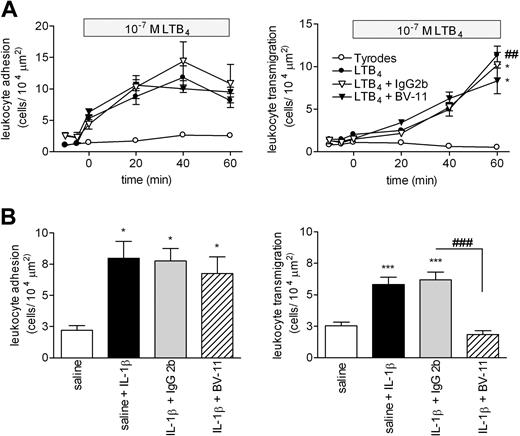

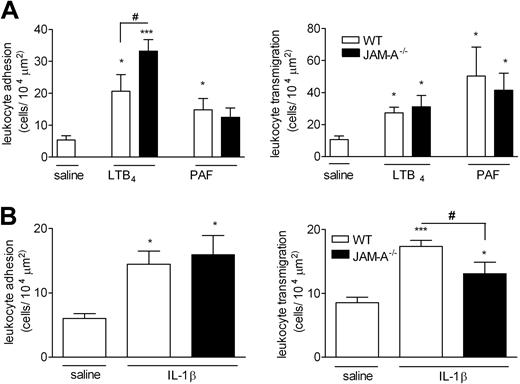

In WT mice, topical application of the chemoattractant LTB4 (10−7 M solution) induced a time-dependent increase in leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration in cremasteric venules that was significantly higher than the levels detected in Tyrode-perfused tissues at 60 minutes after initiation of the superfusion (Figure 1A). Pretreatment of mice with the blocking anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11 (or a control mAb) had no significant effect on LTB4-induced responses. In contrast, pretreatment of mice with mAb BV-11 significantly suppressed leukocyte transmigration, but not adhesion, induced by IL-1β (Figure 1B). The profile of responses elicited by these stimuli, and also PAF, was next investigated in JAM-A−/− mice (Figure 2A). Topical application of LTB4 and PAF (using 10−7 M solutions) induced significant leukocyte adhesion and transmigration responses in both WT and JAM-A−/− mice with no significant differences in transmigration responses detected between the 2 groups of animals. Interestingly however, LTB4-induced adhesion was significantly enhanced in JAM-A−/− animals (46% increase) compared with the responses seen in WT mice. In agreement with the antibody-blockade results, leukocyte transmigration, but again not adhesion, elicited by IL-1β was significantly suppressed in JAM-A−/− mice compared with responses detected in WT animals (52% reduction; P < .05) (Figure 2B). Of relevance, mAb BV-11 had no inhibitory effect on IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration in JAM-A−/− mice, indicating its specificity for JAM-A inhibition (data not shown).

Effect of anti-JAM-A mAb (BV-11) on leukocyte responses in LTB4- and IL-1β-stimulated murine cremasteric venules as observed by intravital microscopy. (A) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control) or of JAM-A mAb or an isotype-matched control mAb (both at a dose of 3 mg/kg); 15 minutes later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for observation by IVM. After taking baseline readings of leukocyte adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel), the cremaster muscle was superperfused with Tyrode solution (control) or with a solution of LTB4 (10−7 M in Tyrode). Leukocyte responses of adhesion and transmigration in selected venules were recorded at 10-minute intervals for a duration of 60 minutes. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-8 mice/group. (B) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control) or of JAM-A mAbs or an isotype-matched control mAb (both at a dose of 3 mg/kg) 15 minutes before intrascrotal injection of IL-1β (50 ng/mouse in 400 μL saline). Control mice received intrascrotal injection of saline. At 4 hours later, the mice were prepared for IVM, and leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-13 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001), and additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (###P < .001).

Effect of anti-JAM-A mAb (BV-11) on leukocyte responses in LTB4- and IL-1β-stimulated murine cremasteric venules as observed by intravital microscopy. (A) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control) or of JAM-A mAb or an isotype-matched control mAb (both at a dose of 3 mg/kg); 15 minutes later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for observation by IVM. After taking baseline readings of leukocyte adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel), the cremaster muscle was superperfused with Tyrode solution (control) or with a solution of LTB4 (10−7 M in Tyrode). Leukocyte responses of adhesion and transmigration in selected venules were recorded at 10-minute intervals for a duration of 60 minutes. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-8 mice/group. (B) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control) or of JAM-A mAbs or an isotype-matched control mAb (both at a dose of 3 mg/kg) 15 minutes before intrascrotal injection of IL-1β (50 ng/mouse in 400 μL saline). Control mice received intrascrotal injection of saline. At 4 hours later, the mice were prepared for IVM, and leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-13 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001), and additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (###P < .001).

Leukocyte responses induced by LTB4, PAF, and IL-1β in cremasteric venules of WT and JAM-A–deficient mice as observed by IVM. (A) The cremaster muscle of WT (□) or JAM-A−/− (■) mice was exteriorized for observations by IVM as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” Tissues were superfused with either saline (control) or with LTB4 or PAF (both with a solution of 10−7 M). Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) after a 60-minute (LTB4) or 120-minute (PAF) superfusion period were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4–6 mice/group. (B) Mice were given intrascrotal saline (□) or intrascrotal IL-1β (50 ng/mouse; ■); 4 hours later, leukocyte responses of adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 6 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05).

Leukocyte responses induced by LTB4, PAF, and IL-1β in cremasteric venules of WT and JAM-A–deficient mice as observed by IVM. (A) The cremaster muscle of WT (□) or JAM-A−/− (■) mice was exteriorized for observations by IVM as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” Tissues were superfused with either saline (control) or with LTB4 or PAF (both with a solution of 10−7 M). Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) after a 60-minute (LTB4) or 120-minute (PAF) superfusion period were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4–6 mice/group. (B) Mice were given intrascrotal saline (□) or intrascrotal IL-1β (50 ng/mouse; ■); 4 hours later, leukocyte responses of adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 6 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05).

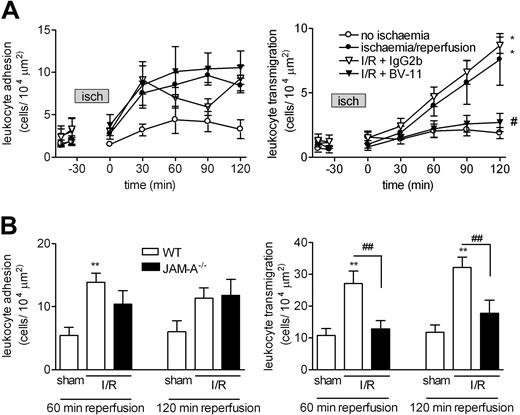

JAM-A mediates leukocyte migration in response to I/R injury at the level of transmigration

These findings were extended to a more pathologic inflammatory scenario, and so responses elicited in the cremaster muscle by I/R injury were investigated (30 minutes of ischemia followed by 120 minutes of reperfusion, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy”). The resultant effect was a time-dependent increase in leukocyte firm adhesion and transmigration during the reperfusion period (Figure 3A). Pretreatment of WT animals with mAb BV-11 before induction of I/R injury resulted in a significant reduction in leukocyte transmigration at 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion compared with control mAb–treated mice (89% inhibition; P < .05). Furthermore, I/R-induced leukocyte transmigration was significantly suppressed in JAM-A−/− mice, with responses at 60 minutes and 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion being suppressed by 88% and 71% compared with WT animals (Figure 3B). Leukocyte firm adhesion was again unaltered following antibody blockade of JAM-A with BV-11 or genetic deletion of JAM-A.

Role of JAM-A in leukocyte responses induced by I/R injury in murine cremasteric venules as observed by IVM. (A) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control), the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11, or an isotype-matched control mAb (both mAbs were given at a dose of 3 mg/kg); 15 minutes later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for observation by IVM. After taking baseline readings of leukocyte adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel), the cremaster muscle was subjected to ischemia for a duration of 30 minutes followed by reperfusion, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion and transmigration were then quantified at 30-minute intervals for 120 minutes. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-8 mice/group. (B) WT and JAM-A−/− mice were subjected to I/R injury, or were sham-operated on (as indicated), and leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified at 60 minutes and 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion. The data represent means (± SEM) from n = 6 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and I/R groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01). Additional statistical comparisons between BV-11–treated versus control mAb–treated groups and WT versus JAM-A−/− are indicated by lines and/or by number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

Role of JAM-A in leukocyte responses induced by I/R injury in murine cremasteric venules as observed by IVM. (A) WT mice were given an intravenous injection of saline (control), the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11, or an isotype-matched control mAb (both mAbs were given at a dose of 3 mg/kg); 15 minutes later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized for observation by IVM. After taking baseline readings of leukocyte adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel), the cremaster muscle was subjected to ischemia for a duration of 30 minutes followed by reperfusion, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion and transmigration were then quantified at 30-minute intervals for 120 minutes. Results are presented as means (± SEM) for n = 4-8 mice/group. (B) WT and JAM-A−/− mice were subjected to I/R injury, or were sham-operated on (as indicated), and leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified at 60 minutes and 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion. The data represent means (± SEM) from n = 6 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and I/R groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01). Additional statistical comparisons between BV-11–treated versus control mAb–treated groups and WT versus JAM-A−/− are indicated by lines and/or by number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

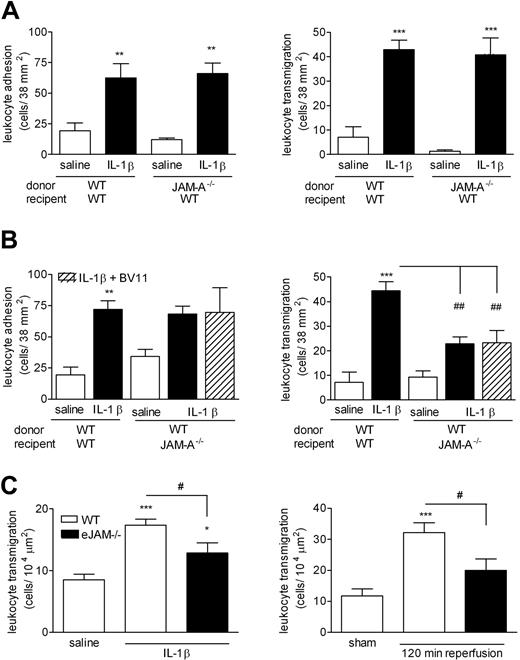

Endothelial-cell JAM-A and not leukocyte JAM-A mediates IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration

Because JAM-A is expressed on both leukocytes13 and endothelial cells,5 the aim of this series of experiments was to ascertain the relative functional role of leukocyte and endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in the murine cremaster muscle model. For this purpose, a cell-transfer model was established that enabled us to quantify the responses of WT or JAM-A–deficient leukocytes in the vasculature of WT or JAM-A−/− mice, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses.” With this approach, bone marrow leukocytes derived from WT mice, labeled with a fluorochrome (Calcein-AM) and injected intravenously into WT animals, exhibited significant adhesion and transmigration responses in IL-1β–stimulated cremaster muscle tissues compared with saline-treated tissues (Figure 4A,B). Leukocytes derived from JAM-A−/− mice also exhibited significant adhesion and transmigration responses when injected into IL-1β–stimulated WT animals, and no significant differences in responses of WT and JAM-A−/− cells were observed in this model (Figure 4A). In contrast, although WT cells injected into JAM-A−/− mice exhibited normal leukocyte adhesion, the transmigration of these cells was significantly reduced compared with the responses of WT leukocytes in WT recipient animals (54% inhibition; Figure 4B). Although the residual transmigration response in this group of mice was not different from control levels, to assess the potential role of leukocyte JAM-A in this response, recipient mice were treated with mAb BV-11 prior to the injection of WT leukocytes. This treatment had no additional inhibitory effect beyond that seen in mice not receiving the blocking mAb. Collectively, the data provide evidence for the involvement of endothelial cell JAM-A, and not leukocyte JAM-A, in leukocyte transmigration in the present model of IL-1β–induced leukocyte migration, and also suggest the involvement of non–JAM-A–dependent adhesion pathways in regulation of leukocyte transmigration under conditions of JAM-A deletion. Further evidence for a functional role of endothelial-cell JAM-A was obtained in studies using a mouse strain specifically lacking eJAM-A−/− in which IL-1β– and I/R injury–induced leukocyte transmigration was significantly suppressed (Figure 4C).

The role of leukocyte and/or endothelial JAM-A in leukocyte responses induced by IL-1β and I/R injury in mouse cremasteric venules. To investigate the potential roles of leukocyte and endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo, a cell-transfer technique was used. (A) Bone marrow leukocytes were isolated from WT or JAM-A−/− mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT recipient mice, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses.” The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and responses of fluorescent leukocytes, firm adhesion (left panel), and transmigration (right panel) were quantified by IVM. (B) In the reverse experiment, leukocytes were isolated from the bone marrow of WT mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT and JAM-A−/− mice. With respect to the latter, to investigate the potential role of leukocyte JAM-A in the noted residual transmigration response, the experiment was repeated in an additional group of mice where the recipient mice were pretreated with the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11 (3 mg/kg, intravenously) 10 minutes prior to the injection of WT leukocytes (▨). The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and responses of fluorescent leukocytes, firm adhesion (left panel), and transmigration (right panel) were quantified by IVM. (C) WT or eJAM−/− mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng) or subjected to sham-operation or I/R injury, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses.” Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified at 4 hours after intrascrotal injection of saline or IL-1β, and at 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion for the I/R studies. The data represent means (± SEM) of responses quantified from n = 3–8 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

The role of leukocyte and/or endothelial JAM-A in leukocyte responses induced by IL-1β and I/R injury in mouse cremasteric venules. To investigate the potential roles of leukocyte and endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo, a cell-transfer technique was used. (A) Bone marrow leukocytes were isolated from WT or JAM-A−/− mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT recipient mice, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses.” The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and responses of fluorescent leukocytes, firm adhesion (left panel), and transmigration (right panel) were quantified by IVM. (B) In the reverse experiment, leukocytes were isolated from the bone marrow of WT mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT and JAM-A−/− mice. With respect to the latter, to investigate the potential role of leukocyte JAM-A in the noted residual transmigration response, the experiment was repeated in an additional group of mice where the recipient mice were pretreated with the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11 (3 mg/kg, intravenously) 10 minutes prior to the injection of WT leukocytes (▨). The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and responses of fluorescent leukocytes, firm adhesion (left panel), and transmigration (right panel) were quantified by IVM. (C) WT or eJAM−/− mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng) or subjected to sham-operation or I/R injury, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Quantification of fluorescent leukocyte responses.” Leukocyte responses of firm adhesion (left panel) and transmigration (right panel) were quantified at 4 hours after intrascrotal injection of saline or IL-1β, and at 120 minutes after initiation of reperfusion for the I/R studies. The data represent means (± SEM) of responses quantified from n = 3–8 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

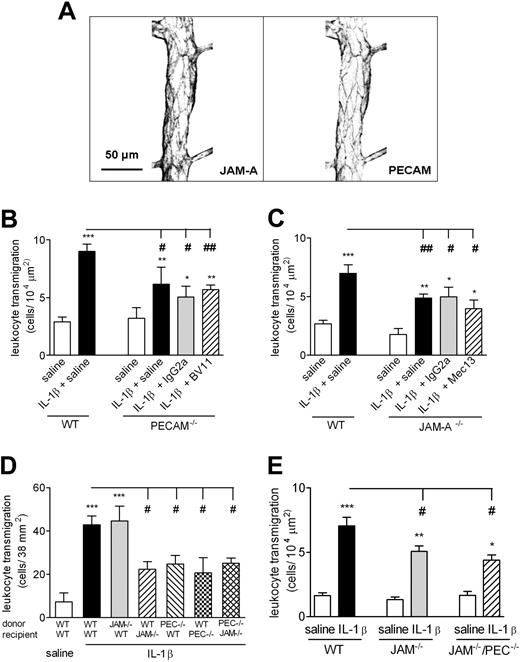

Dual blockade/genetic deletion of JAM-A and PECAM-1 do not lead to an additive inhibitory effect on neutrophil transmigration

JAM-A and PECAM-1 exhibit numerous common features in terms of their expression and functional profiles,17 and in murine cremasteric venules, JAM-A is expressed at endothelial-cell junctions in a similar pattern to that seen with PECAM-1 (Figure 5A). Despite this, the potential additive/cooperative role of these molecules in mediating neutrophil transmigration in vivo has not been investigated. To address this issue, a series of experiments were performed aimed at investigating the effect of dual blockade of JAM-A– and PECAM-1–dependent pathways using either pharmacologic inhibitors and/or genetic deletion of the molecules.

Effect of dual blockade of JAM-A–dependent and PECAM-1–dependent pathways on IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration through mouse cremasteric venules as observed by IVM. (A) The expression profiles of JAM-A and PECAM-1 in representative cremasteric venules of WT mice. Unstimulated cremaster muscles were immunostained for the expressions of JAM-A and PECAM-1, as detailed in “Immunofluorescence labeling and analysis of cremaster muscle tissues by confocal microscopy.” Samples were observed using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL confocal laser-scanning microscope. Scale bar equals 50 μm. (B,C) WT, PECAM-1−/−, or JAM-A−/− mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng). Additional groups of mice were pretreated with the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11, the anti–PECAM-1 mAb Mec13.3, or appropriate control mAbs (all at 3 mg/kg intravenously), as indicated. At 4 hours after the administration of IL-1β, cremaster muscles were exteriorized, and leukocyte transmigration was quantified by IVM, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” (D) Leukocytes were isolated from the bone marrow of WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− recipient mice. The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and transmigration of fluorescent leukocytes was quantified by IVM. (E) WT, JAM−/−, or JAM-A−/−/PECAM-1−/− double-deficient mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, leukocyte transmigration was quantified. The data represent means (± SEM) of responses quantified from n = 3–12 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

Effect of dual blockade of JAM-A–dependent and PECAM-1–dependent pathways on IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration through mouse cremasteric venules as observed by IVM. (A) The expression profiles of JAM-A and PECAM-1 in representative cremasteric venules of WT mice. Unstimulated cremaster muscles were immunostained for the expressions of JAM-A and PECAM-1, as detailed in “Immunofluorescence labeling and analysis of cremaster muscle tissues by confocal microscopy.” Samples were observed using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL confocal laser-scanning microscope. Scale bar equals 50 μm. (B,C) WT, PECAM-1−/−, or JAM-A−/− mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng). Additional groups of mice were pretreated with the anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11, the anti–PECAM-1 mAb Mec13.3, or appropriate control mAbs (all at 3 mg/kg intravenously), as indicated. At 4 hours after the administration of IL-1β, cremaster muscles were exteriorized, and leukocyte transmigration was quantified by IVM, as detailed in “Materials and methods, Intravital microscopy.” (D) Leukocytes were isolated from the bone marrow of WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− mice, labeled with calcein-AM, and injected intravenously into WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− recipient mice. The mice were then injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, the cremaster muscle was exteriorized, and transmigration of fluorescent leukocytes was quantified by IVM. (E) WT, JAM−/−, or JAM-A−/−/PECAM-1−/− double-deficient mice were injected intrascrotally with saline or IL-1β (50 ng); 4 hours later, leukocyte transmigration was quantified. The data represent means (± SEM) of responses quantified from n = 3–12 mice/group. Statistically significant differences between control and stimulated groups are shown by asterisks (*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (#P < .05, ##P < .01).

In initial experiments, the effects of anti–JAM-A and anti–PECAM-1 blocking mAbs were tested on IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration in PECAM-1−/− and JAM-A−/− mice, respectively (Figure 5B-C). While both the PECAM-1−/− and JAM-A−/− mice exhibited significantly reduced levels of leukocyte transmigration in response to IL-1β compared with that of WT mice (31% and 49%, respectively), pretreatment of these animals with blocking anti–JAM-A (BV-11) or anti–PECAM-1 (Mec13.3) mAbs did not lead to a greater level of inhibition to that seen in mice treated with either intravenous saline or isotype-matched control mAbs. These findings suggest that JAM-A does not act in an additive manner with PECAM-1 in mediating neutrophil transmigration. This possibility was further investigated using the cell-transfer technique detailed in the previous section.

Briefly, WT and JAM-A−/− leukocytes, when injected intravenously into WT recipient mice, exhibited comparable transmigration responses in IL-1β–stimulated tissues, whereas WT leukocytes exhibited a significantly reduced transmigration response in JAM-A−/− recipients (Figure 5D). In contrast, PECAM-1−/− leukocytes injected into WT recipients exhibited a similar reduced transmigration response to that seen when WT cells were injected into PECAM-1−/− recipients. Furthermore, conditions where both JAM-A– and PECAM-1–mediated pathways were both abolished (ie, by injecting PECAM-1−/− leukocytes into JAM-A−/− recipient mice) resulted in again a similar level of transmigration to that seen when either of the pathways was blocked individually (Figure 5D). Finally, the effect of dual deletion of JAM-A and PECAM-1 was investigated in a novel mouse strain deficient in both molecules (Figure 5E). As shown in Figure 5E, leukocyte transmigration induced by IL-1β was significantly suppressed in both JAM-A−/− and JAM-A−/−/PECAM-1−/− mice (31% and 49%, respectively), compared with WT mice, but no significant difference was observed between the 2 strains of animals. Collectively, the findings of these multiple studies show that inhibition of JAM-A and PECAM-1 does not act in an additive manner.

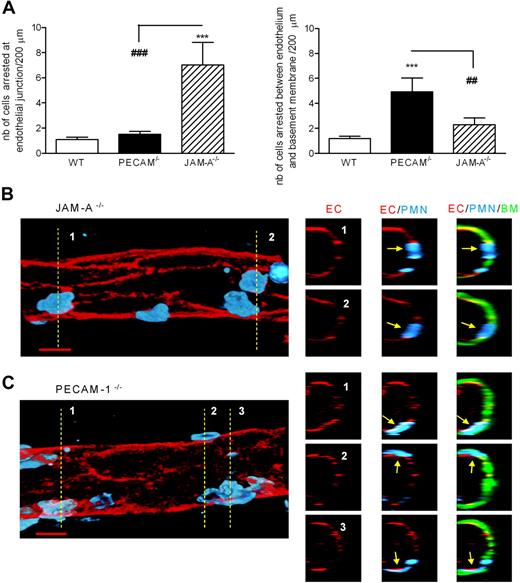

Inhibition of leukocyte migration in JAM-A−/− or PECAM-1−/− mice occurs at different and sequential stages of the emigration process

Because dual blockade/deletion of JAM-A and PECAM-1 did not result in an additive inhibitory effect, we hypothesised that JAM-A and PECAM-1 may be regulating leukocyte transmigration at different but sequential steps of the emigration process. To address this possibility, IL-1β–stimulated cremasteric tissues from WT, JAM-A−/−, and PECAM-1−/− mice were immunostained with markers for endothelial cells, endothelial-cell basement membrane, and neutrophils, and the site of arrest of leukocytes were analyzed and quantified by confocal microscopy. Although a low and comparable number of neutrophils were found in WT and PECAM-1−/− mice to be arrested at the level of the endothelium (apparently at the level of the endothelial-cell junctions), a significantly higher number of neutrophils were found at these sites in JAM-A−/− mice (approximately 5.5-fold increase above levels in WT mice; Figure 6A,B). In contrast, while JAM-A−/− mice exhibited a low number of neutrophils arrested between the endothelium and its associated basement membrane (no significant difference from WT mice), PECAM-1−/− mice showed a significantly higher level of neutrophils arrested below the endothelial-cell basement membrane (approximately 2-fold increase above levels in WT mice; Figure 6A,C). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that JAM-A and PECAM-1 can mediate neutrophil transmigration by mediating sequential steps in the process of leukocyte migration through venular walls (ie, emigration through the endothelium and its associated basement membrane, respectively).

JAM-A−/− and PECAM−/− mice exhibit different profiles in terms of site of arrest of transmigrating leukocytes in IL-1β–stimulated cremaster muscle tissues. IL-1β–stimulated cremaster muscle tissues from WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− mice were immunostained and prepared for analysis by confocal microscopy as detailed in “Immunofluorescence labeling and analysis of cremaster muscle tissues by confocal microscopy.” Briefly, tissues were immunostained for endothelial cell junctions using an anti–PECAM-1 mAb (in WT and JAM-A−/− mice) or an anti–ICAM-2 mAb (in PECAM-1−/− mice) (shown in red), the endothelial cell basement membrane using an anti–collagen IV Ab (shown in green), and neutrophils using an anti–MRP-14 mAb (shown in blue). The localization of neutrophils in relation to the endothelium and its basement membrane was determined and quantified by analyzing acquired three-dimensional images of whole blood vessels. (A) The number of neutrophils quantified to be at the level of the endothelium, arrested between endothelial cell junctions (left panel), or arrested between the endothelium and the endothelial cell basement membrane (right panel), in different strains of mice. Samples were observed using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL confocal laser-scanning microscope, and the images were subsequently analyzed using Volocity three-dimensional rendering software. The number of leukocytes arrested within the venular walls was quantified in 200-μm sections (n = 5–12 cremaster muscle tissues per group). (B,C) Representative longitudinal (left panels) and cross-sectional (multiple small panels on the right) images of venules from JAM-A−/− and PECAM−/− mice, respectively. The left panels show three-dimensional images of venules stained for endothelial-cell junctions (red) and neutrophils (blue) only. The images on the right were obtained by cutting a cross-section (1-μm thick) of the venules on the left along the indicated dotted lines. The cross-sectional images corresponding to each of the numbered dotted lines are presented as a panel of 3 images in a row, showing the staining of endothelial-cell junctions (EC; red), neutrophils (PMN; blue), and the endothelial-cell basement membrane (BM; green). The arrows show the location of selected neutrophils, clearly indicating arrest of neutrophils at endothelial-cell junctions in the JAM-A−/− mice and between the endothelium and the endothelial-cell basement membrane in the PECAM-1−/− mice. Scale bar equals 10 μm. Statistically significant differences between WT and KO groups are shown by asterisks (***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (##P < .01, ###P < .001).

JAM-A−/− and PECAM−/− mice exhibit different profiles in terms of site of arrest of transmigrating leukocytes in IL-1β–stimulated cremaster muscle tissues. IL-1β–stimulated cremaster muscle tissues from WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− mice were immunostained and prepared for analysis by confocal microscopy as detailed in “Immunofluorescence labeling and analysis of cremaster muscle tissues by confocal microscopy.” Briefly, tissues were immunostained for endothelial cell junctions using an anti–PECAM-1 mAb (in WT and JAM-A−/− mice) or an anti–ICAM-2 mAb (in PECAM-1−/− mice) (shown in red), the endothelial cell basement membrane using an anti–collagen IV Ab (shown in green), and neutrophils using an anti–MRP-14 mAb (shown in blue). The localization of neutrophils in relation to the endothelium and its basement membrane was determined and quantified by analyzing acquired three-dimensional images of whole blood vessels. (A) The number of neutrophils quantified to be at the level of the endothelium, arrested between endothelial cell junctions (left panel), or arrested between the endothelium and the endothelial cell basement membrane (right panel), in different strains of mice. Samples were observed using a Zeiss LSM 5 PASCAL confocal laser-scanning microscope, and the images were subsequently analyzed using Volocity three-dimensional rendering software. The number of leukocytes arrested within the venular walls was quantified in 200-μm sections (n = 5–12 cremaster muscle tissues per group). (B,C) Representative longitudinal (left panels) and cross-sectional (multiple small panels on the right) images of venules from JAM-A−/− and PECAM−/− mice, respectively. The left panels show three-dimensional images of venules stained for endothelial-cell junctions (red) and neutrophils (blue) only. The images on the right were obtained by cutting a cross-section (1-μm thick) of the venules on the left along the indicated dotted lines. The cross-sectional images corresponding to each of the numbered dotted lines are presented as a panel of 3 images in a row, showing the staining of endothelial-cell junctions (EC; red), neutrophils (PMN; blue), and the endothelial-cell basement membrane (BM; green). The arrows show the location of selected neutrophils, clearly indicating arrest of neutrophils at endothelial-cell junctions in the JAM-A−/− mice and between the endothelium and the endothelial-cell basement membrane in the PECAM-1−/− mice. Scale bar equals 10 μm. Statistically significant differences between WT and KO groups are shown by asterisks (***P < .001). Additional statistical comparisons are indicated by lines and number signs (##P < .01, ###P < .001).

Discussion

JAM-A is a type I transmembrane protein with 2 extracellular Ig-like domains that is expressed on endothelial and epithelial cells and also on leukocytes, platelets, and erythrocytes.2,7 Evidence for the involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte migration was presented almost 8 years ago,5 but since then, the existence of some inconsistent findings related to the functional role of this molecule in different inflammatory models has caused some controversy in the field.5,9–11 In the present study, using both a functional blocking mAb and JAM-A–deficient mice, direct evidence is presented for the involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo as observed by intravital microscopy. The findings also indicate that the functional role of this adhesion molecule in mediating leukocyte transmigration is stimulus specific, a phenomenon that may provide some explanation for the inconsistent observations related to JAM-A in different inflammatory models. Furthermore, within the acute models of neutrophil emigration used, the results indicate a role for endothelial cell and not leukocyte JAM-A in this process, and also suggest that JAM-A acts in sequence with PECAM-1 to mediate an efficient leukocyte transmigration response.

The cremasteric microcirculation, as studied by IVM, was used for directly investigating the role of JAM-A in leukocyte migration through inflamed venular walls. Using this model, pretreatment of WT mice with the blocking anti–JAM-A mAb BV-11 or the use of JAM-A–deficient mice indicated a significant role for JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration elicited by IL-1β and I/R injury, but not by the chemoattractants LTB4 or PAF. These findings provide the first indication that JAM-A–mediated leukocyte transmigration can be stimulus-dependent. Of note, the inhibitory effect seen in mice treated with BV-11 was always greater than that seen in JAM-A−/− mice, suggesting the possibility of compensatory mechanisms in the latter. The nature of such compensatory pathways in the JAM-A−/− animals is at present unclear, but the findings suggest that this does not involve PECAM-1, as will be discussed. Furthermore, while JAM-A blockade/deletion exerted an inhibitory effect on leukocyte migration, specifically at the transmigration phase, in certain inflammatory scenarios (eg, LTB4-induced inflammation), stimulated leukocyte adhesion was significantly enhanced in JAM-A−/− mice. The reason for this finding is at present unclear, but may be related to the phenomena reported by Corada et al13 detailing that JAM-A–deficient leukocytes exhibit a defect in their motility and hence exhibit increased adhesion to protein-coated surfaces.

The underlying reason for the observed stimulus-dependent ability of JAM-A to mediate leukocyte transmigration is at present unknown. Interestingly, however, these findings are very similar to our earlier results with respect to the profiles of PECAM-1– and ICAM-2–dependent leukocyte transmigration.14,15 Specifically, we have previously found that IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration is dependent on both PECAM-1 and ICAM-2, while transmigration elicited by TNFα occurs independently of these endothelial-cell junctional molecules.14,15 Of importance, like the chemoattractants LTB4 and PAF,24,25 stimuli exhibiting JAM-A–independent leukocyte transmigration in the present study, TNFα can also directly activate leukocytes.15 Hence, a simple but potentially possible explanation of these findings is that stimuli that induce leukocyte transmigration via activation of endothelial cells (eg, IL-1β26–28 ) activate adhesion pathways involving endothelial cell–associated JAM-A, PECAM-1, and ICAM-2. Conversely, stimuli that directly activate neutrophils (eg, TNFα, LTB415,24,29 ) bypass the need for these molecules and may use other mechanisms for transendothelial-cell migration (eg, β2/ICAM-1 and/or pathways involving other endothelial-cell junctional molecules such as ESAM [endothelial cell–selective adhesion molecule]). ESAM is an Ig-superfamily member distantly related to JAM-A that may mediate chemoattractant-induced neutrophil transmigration, as ESAM−/− mice exhibit reduced leukocyte transmigration in response to both IL-1β and TNFα.30 These findings indicate that ESAM mediates leukocyte transmigration via a different mechanism to that mediated by JAM-A, PECAM-1, and ICAM-2, and that it may support JAM-A/PECAM-1/ICAM-2–independent neutrophil transmigration. Other factors may also account for stimulus-specific mechanisms of leukocyte transmigration. For example, Schenkel and colleagues have recently reported that the ability of PECAM-1 to mediate neutrophil transmigration in mouse models of inflammation is dependent on the strain of mouse used, suggesting the existence of a genetic basis for detectable PECAM-1–mediated responses.31 A similar phenomenon may apply to JAM-A– and ICAM-2–mediated events, an issue that is currently under investigation in our laboratory. It is also potentially possible that the stimulus-dependent ability of certain adhesion pathways to mediate leukocyte transmigration may be related to the microvascular bed under investigation (ie, related to the level of junctional molecules expressed by different vascular endothelium). Addressing such possibilities will form the basis of our future investigations.

JAM-A is expressed on both murine leukocytes13 and murine endothelial cells,5,13 where its expression is restricted to cell-cell junctions (Figure 5A with respect to cremasteric venules and Padura et al,5 where we show that JAM-A is localized at tight junctions by several means both in vitro and in vivo). As part of the present studies, we sought to investigate the potential roles of leukocyte versus endothelial-cell JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in the cremaster muscle model. Using a cell-transfer technique and a mouse strain deficient in endothelial-cell JAM-A, evidence was obtained for the involvement of endothelial-cell JAM-A in IL-1β– and I/R-induced leukocyte transmigration. A key role of endothelial-cell JAM-A in these responses is in line with our overall hypothesis that endothelial cell–activating stimuli induce JAM-A–mediated leukocyte transmigration. The present results are also in agreement with the findings of Khandoga et al, who, using a model of hepatic ischemia, found that neutrophil transmigration was equally reduced in JAM-A−/− and endothelial cell–specific JAM-A−/− animals compared with WT mice.12 In contrast, Corada and colleagues collected evidence for a role of neutrophil JAM-A in directional movement and diapedesis in vitro and in vivo in a model of I/R injury and of thioglycollate-induced peritonitis.13 The reasons behind the difference in these findings is at present unclear, but may be related to (1) the different inflammatory models, and (2) the differences in the in vivo test periods of the inflammatory reactions used. Overall, it is highly probable that the relative role of JAM-A, and indeed other endothelial-cell junctional molecules, in leukocyte transmigration is governed by the vascular bed and the temporal phase of the inflammatory response under investigation.

In the light of the structural, expression profile, and functional similarities between JAM-A and PECAM-1, as previously reported17 and also detailed here, in a final series of experiments the potential additive/synergistic roles of these molecules in leukocyte transmigration was investigated. For this purpose, a number of experimental approaches were used to block both JAM-A–dependent and PECAM-1–dependent leukocyte transmigration pathways, including testing the effects of neutralizing anti–PECAM-1 and anti–JAM-A mAbs in JAM-A−/− and PECAM-1−/− mice, respectively, as well as investigating leukocyte transmigration in a novel mouse strain deficient in both JAM-A and PECAM-1. Collectively, the findings indicated that dual blockade/deletion of PECAM-1 and JAM-A does not result in a greater level of inhibition of IL-1β–induced neutrophil transmigration above that seen under conditions of blockade/deletion of JAM-A alone. Further evidence to support this came from studies where we performed cell transfer between WT, JAM-A−/−, or PECAM-1−/− mice. Overall, a number of conclusions can be made from these findings. (1) The residual IL-1β–induced leukocyte transmigration response detected in JAM-A−/− or PECAM-1−/− mice is not mediated by PECAM-1 or JAM-A, respectively. These findings indicate that JAM-A and PECAM-1 do not compensate for one another in the relevant KO models. (2) The cell-transfer experiments indicated a key difference in the mechanism via which JAM-A and PECAM-1 mediate leukocyte transmigration. Specifically, while in agreement with previous in vitro32,33 and in vivo34 results, PECAM-1–mediated leukocyte transmigration required leukocyte PECAM-1 and endothelial-cell PECAM-1 to the same extent (ie, exhibiting homophilic interaction), and the need for only endothelial-cell JAM-A highlighted a heterophilic JAM-A–dependent pathway involved in leukocyte transmigration. At present, the identification of the leukocyte ligand for endothelial-cell JAM-A in vivo is unknown, though in vitro studies have identified LFA-1 as a potential JAM-A ligand.8

Because dual blockade/deletion of JAM-A and PECAM-1 did not result in an additive inhibitory effect, we hypothesized that these molecules may mediate different steps in the emigration process and hence act in sequence in mediating leukocyte migration through venular walls. Of relevance, we have previously shown that PECAM-1 plays a role in neutrophil migration through the endothelial-cell basement membrane.15,34 To extend these findings, we sought to investigate the site of arrest of neutrophils in IL-1β–stimulated tissues of JAM-A−/− mice, in comparison with tissues from PECAM-1−/− mice, as analyzed by confocal microscopy. The results clearly indicated that in JAM-A KO mice, neutrophils were largely arrested at the level of the endothelium (apparently trapped at endothelial-cell junctions), while in PECAM-1 KO mice, in agreement with our previous findings, inhibition of neutrophil transmigration occurred at the level of the endothelial-cell basement membrane. Collectively, these results demonstrate that JAM-A and PECAM-1 can mediate different but sequential stages of the emigration process, namely migration through the endothelium and through the endothelial-cell basement membrane, respectively. Details of the mechanism associated with the former is at present unclear, but the latter appears to be regulated via PECAM-1–mediated up-regulation of integrins such as α6β1.34

In summary, the findings of this study has provided direct and conclusive evidence for the involvement of JAM-A in leukocyte transmigration in vivo. In the model used, the ability of JAM-A to mediate neutrophil transmigration was stimulus dependent and only required endothelial-cell JAM-A and not leukocyte JAM-A. Furthermore, the study provides evidence for the ability of JAM-A and PECAM-1 to mediate leukocyte transmigration at distinct but sequential steps in the process of leukocyte migration through venular walls.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the European Community (NoE MAIN 502935, no. LSHG-CT-2004–503573; NoE EVGN 503254), Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (GRK 438), and the British Heart Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: A.W. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; C.A.R. and A.K. designed and performed experiments and contributed to data analysis and interpretation; M.C. provided key reagents; M.-B.V. and C.S. performed experiments; D.H. contributed to the design of research; E.D. provided key reagents and contributed to design of research, data analysis, and interpretation and the writing of the manuscript; F.K. contributed to design of research, data analysis, and interpretation and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and S.N designed and supervised the research, contributed to data analysis and interpretation and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Data presented in this manuscript are part of the doctoral thesis of C.A.R. S. N. and F. K. share joint last authorship.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Sussan Nourshargh, Cardiovascular Medicine Unit, National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, Du Cane Road, London W12 0NN; e-mail: s.nourshargh@imperial.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal