Abstract

Prognosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–related non-Hodgkin lymphoma has improved since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Burkitt lymphomas (BLs) still have poor outcome in patients with bone marrow (BM) or central nervous system (CNS) involvement when treated with standard-dose chemotherapy. We have prospectively evaluated the LMB86 regimen in 63 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients with stage IV (BM and/or CNS involvement) BL consecutively recruited between November 1992 and January 2006. At BL diagnosis, the median CD4 cell count was 239 × 106/L (range, 16-1188 × 106/L). BM and CNS involvement were present in 55 (80%) and 48 (76%) patients, respectively. Forty-four patients (70%) achieved complete response. Seven treatment-related deaths occurred and all patients experienced severe BM toxicity. With a median follow-up of 66 months (range, 6-165 months), 11 patients relapsed. The estimate 2-year overall survival and disease-free survival were 47.1% (95% CI, 34-59.1) and 67.8% (95% CI, 51-80), respectively. We identified 2 poor prognosis factors: low CD4 count and ECOG more than 2. Patients with 0 or 1 factor had good outcome (2-year survival: 60%) contrasting with patients with 2 factors (2-year survival: 12%). We conclude that LMB86 regimen is highly effective in advanced HIV-related BL and should be proposed for patients with CD4 count higher than 200 × 106/L or ECOG of 2 or less.

Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive B-cell proliferation with a nearly 100% growth-phase fraction.1 Outside some endemic areas, BL affects mainly children and accounts for only 1% to 2% of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs).1 It may present as a very aggressive disseminated disease with bone marrow (BM) and/or central nervous system (CNS) involvement.1-3 As the Ann Arbor staging system is unable to fully describe the extranodal involvement, the St Jude/Murphy system is usually used to stage BL.1 St Jude/Murphy stage IV designates exclusively the high-risk group of patients with BM and/or CNS involvement

Standard chemotherapy regimens have shown poor results with prolonged survival probability less than 30% in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–negative adult patients and less than 20% for patients with stage IV despite intrathecal therapy.2 Short but intensive regimens containing very high-dose methotrexate (MTX) alternated with very high-dose cytarabine and associated with intrathecal prophylaxis are associated with an increased probability of survival.1,4-9 The pilot LMB86 study improved survival in patients with stage IV disease.10 LMB11,12 or similar protocols as CODOX-M/IVAC (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, high-dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, and high-dose cytarabine),6 hyper–CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone, methotrexate and cytarabine),5 or B-NHL13 demonstrated similar results in the HIV-negative adult population with long-term survival higher than 70% in patients with stage IV disease.

Even since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996, non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) remains a major cause of mortality in patients infected with HIV.14-25 BL accounts for 25% to 40% of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–related lymphomas (ARLs), even affecting nonimmunocompromised patients.14,26-29 In a pre-HAART study evaluating an intensive cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP)–derived chemotherapy regimen (LNH84), the toxicity was acceptable but the 2-year overall survival (OS) was less than 20% in the 21 patients with BL and BM involvement.30 However, prognosis of ARL has improved in the last decade, after the advent of HAART. The median survival in those patients is now quite similar to the general population with NHL.14,15,25,31,32 Furthermore, HAART, restoring immune function, has improved tolerance to chemotherapy and most patients are now treated with standard-dose regimen.33-35 As in the pre-HAART era prognosis of AIDS-related BL treated with standard- or low-dose chemotherapy was similar to other ARLs,36 most HIV-infected patients with BL were still being treated with standard-dose regimen after 1996.37 Lim et al have recently compared survival of patients with AIDS-related NHL in pre- and post-HAART era. In opposition to what was observed in NHL, the prognosis of BL remained poor despite the introduction of effective antiretroviral therapy. The complete response (CR) rate remained low, around 35% (23% in case of CNS involvement), and OS is less than 15% at 2 years all stages mixed up.37 So, even in the HAART era, the treatment of patients with AIDS-related BL is still challenging.

As the LMB regimen is the gold standard treatment in France for advanced-stage BL, we thus decided to evaluate prospectively the LMB86 regimen10 in 63 HIV-infected patients with stage IV BL. A CR was obtained in 70% of patients and the 2-year OS was 47.1%. We demonstrated that LMB86 is an effective regimen for such aggressive ARL.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

Patients were required to have biopsy- or cytology-proven previously untreated BL and a positive serology for HIV. All patients should have BM or CNS involvement as defined in stage IV of the St Jude/Murphy system.1 Patients without BM or CNS disease were not included and treated with less intensive regimens. CNS disease was defined as the presence of more than 5/mm3 blasts cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF leukemia), cranial nerve palsy not related to a facial tumor, clinical signs of spinal cord compression, and/or intracranial mass. All consecutive patients who met those criteria were enrolled, whatever their performance or HIV immunovirologic status, between November 1992 and January 2006. The study was conducted in accordance with European legislation on biomedical research. All pathological samples were reviewed by a single hematopathologist and were classified as classical BL, Burkitt-like lymphoma (BLL), and BL with plasmacytoid differentiation (BLP) according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria.38 Growth phase fraction was determined using Ki67 immunostaining. Nearly 100% of tumoral cells had to be positive for Ki67. Cytogenetic study was performed when adequate samples were available. Specific Burkitt translocations, t(8;14), t(8;22), and t(2;8), were designated as Ig-myc.

Evaluation of disease activity

All patients underwent staging evaluation, which included physical examination; blood counts and chemistries; blood smears; chest x-ray; computerized tomography of the abdomen, pelvis, brain, or sites of known disease activity; BM examination; and cytologic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Initial bulky disease was defined by a tumor size larger than 10 cm.

HIV status evaluation

Absolute lymphocyte count (ALC), CD4 and CD8 cell count, plasma HIV RNA, and medical HIV history including nadir of the CD4 cell count were recorded at entry.

Study design and treatment

This was a prospective therapeutic trial in a single clinical tertiary center. The detailed protocol scheme is given in Table 1. Briefly, the LMB86 protocol for stage IV combined the following: (1) cytoreductive phase with low-dose cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and steroid therapy (COP); (2) induction starting one week after COP and consisting of 2 consecutive courses of COPADM with high-dose (8 g/m2) methotrexate; (3) consolidation phase including 2 courses of CYVE with high-dose cytarabine and etoposide; (4) maintenance with 4 courses combining previous drugs with lower dosage.10 Subcutaneous granulocyte–colony-stimulating factor was used at each cycle. Dose could be adjusted in case of hepatic or renal failure, but no dose adjustment was planned according to hematologic toxicity, and courses were delayed until the granulocyte count increased to more than 1000 × 106/L and the platelet count to more than 50 × 109/L. All patients received 10 intrathecal injections of MTX, cytarabine, and steroids. In case of severe drug-induced toxicity occurring in patients yet in CR, the maintenance phase could be shortened.

LMB86 chemotherapy regimen

| Drug, dosage/d . | Day . |

|---|---|

| Cytoreductive phase, COP | |

| Vincristine, 2 mg | d1 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 300 mg/m2 | d1 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| Induction | |

| COPADM 1 | |

| Vincristine, 2 mg | d1 |

| Methotrexate, 8 g/m2 | d1 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 500 mg/m2 | d2 to d4 |

| Adriamycin, 60 mg/m2 | d2 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| COPADM 2 | |

| Idem with vincristine, 2 mg | d1, d6 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 1000 mg/m2 | d2 to d4 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| Consolidation, CYVE, ×2 | |

| Etoposide, 200 mg/m2 | d2 to d5 |

| ARA-C, 3 g/m2 | d2 to d5 |

| ARA-C, 50 mg/m2 | d1 to d4* |

| Drug, dosage/d . | Day . |

|---|---|

| Cytoreductive phase, COP | |

| Vincristine, 2 mg | d1 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 300 mg/m2 | d1 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| Induction | |

| COPADM 1 | |

| Vincristine, 2 mg | d1 |

| Methotrexate, 8 g/m2 | d1 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 500 mg/m2 | d2 to d4 |

| Adriamycin, 60 mg/m2 | d2 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| COPADM 2 | |

| Idem with vincristine, 2 mg | d1, d6 |

| Cyclophosphamide, 1000 mg/m2 | d2 to d4 |

| Prednisone, 60 mg/m2 | d1 to d7 |

| Consolidation, CYVE, ×2 | |

| Etoposide, 200 mg/m2 | d2 to d5 |

| ARA-C, 3 g/m2 | d2 to d5 |

| ARA-C, 50 mg/m2 | d1 to d4* |

MTX infusion was followed at hour 24 by folinic acid rescue (50 mg every 6 hours × 3 days). Maintenance therapy consisted of 4 sequences: (1) vincristine 2 mg d1, methotrexate 8 g/m2 d1, cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 d2-d3, adriamycin 60 mg/m2 d3, prednisone 60 mg/m2 d1- d5; (2) etoposide 150 mg/m2 d1-d3, ARA-C 100 mg/m2 SC d1-d5; (3) same as sequence no. 1 but without high-dose MTX; and (4) same as sequence no. 2. Intrathecal injection: MTX + ARA-C + HDR d1, d3, and d5 of COP; d2, d4, and d6 of COPADM 1 and COPADM 2; d2 of sequence 1.

Twelve-hour infusion before high-dose ARA-C.

Trimethoprime-sulfamethoxazole was used as pneumocystis and toxoplasma prophylaxis but was suspended during high-dose MTX. Antiretroviral therapy was maintained in patients already treated and introduced during the second COPADM course in naive patients. Zidovudine was avoided when possible.

Chemotherapy relative dose evaluation

The evaluation of the relative dose (the ratio of the delivered dose to the theoretical dose) was calculated for adriamycin and methotrexate on the 2 courses of COPADM and for cytarabine on the 2 courses of CYVE. For analysis, cutoff value was 75%.

Statistical analysis

Study end points were response rate, OS, event-free survival (EFS), progression-free survival (PFS), and disease-free survival (DFS). This was an intent-to-treat analysis. Response evaluation was performed after completion of consolidation phase (after CYVE2) and every 6 months thereafter. Complete remission (CR) was defined as the resolution of all evidence of disease, as determined by clinical, radiologic, and BM and CSF evaluation. OS was calculated from the time of diagnostic of BL until date of death from any cause. EFS was calculated from the date of BL diagnosis to the date of progression or death due to any cause. PFS was calculated from the date of BL diagnosis to the date of progression or death from BL. The duration of disease-free survival (DFS) was calculated for patients who achieved CR, from the date of CR to the date of progression. OS and DFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method.39

A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to identify statistically significant differences in survival and to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence interval (CIs).40 Covariates identified by the univariate analysis with P < .10 were analyzed in a multivariate model. A forward stepwise selection procedure was used to assess the relative role of prognostic factors. The level of significance was .05. For the prognosis analysis, all parameters were analyzed as categoric variables. The cutoff points chosen were based on clinical relevance.

The covariates analyzed at diagnosis in the prognosis model were age, CD4 cell count, CD8 cell count, ALC, plasma HIV RNA load, nadir CD4 cell count, prior AIDS, HAART at entry, peripheral blasts cells, bulkytumor, cranial nerve palsy or spinal cord injury, CSF leukemia, cytogenetic study, serum LDH levels, hemoglobin level, platelet count, performance status, IPI risk group, B symptoms, histologic type, and methotrexate dose intensity at COPADM1. We used nonmodified IPI rather than age-adjusted IPI (aaIPI) to take the highly extranodal dissemination of disease into account. Furthermore, aaIPI was unable to discriminate a well-balanced group, as 95% of patients had high-risk aaIPI. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata computer package (Stata Statistical Software; Stata, College Station, TX).

As the introduction of HAART during chemotherapy was planned for all patients and was not a baseline covariate, it was not included in the model but its prognostic value was discussed.

Results

Patient characteristics

Sixty-three consecutive patients entered the study (Table 2). Only 7 were included before 1996. Prior to BL diagnosis, 36 patients (57%) had asymptomatic HIV infection, 14 (22%) had symptomatic HIV infection in the absence of AIDS, and 13 (21%) had full-blown AIDS. Thirty-three patients (52%) were on antiretroviral therapy, including 31 patients on HAART. Sixteen (27%) had a plasma HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL, and in 44 patients the median value for plasma HIV RNA was 38 000 copies/mL (range, 599-3 281 900 copies/mL). The median CD4 cell count was 239 × 106/L (range, 16-1188 × 106/L). Thirteen patients had a CD4 count lower than 100 × 106/L and 6 lower than 50 × 106/L. The median CD8 cell count was 1074 × 106/L (range, 40-6356 × 106/L). The median nadir CD4 cell count was 205 × 106/L (range, 7-780 × 106/L).

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristics . | No. . |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 63 |

| Sex, no. M/F | 56/7 |

| Median age, y (range) | 40 (20-57) |

| HIV transmission, no. | |

| Homosexual | 38 |

| Heterosexual | 13 |

| IV drug user | 10 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| CD4 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 239 |

| Range | 16-1188 |

| No. less than 100 | 13/63 |

| CD8 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 1074 |

| Range | 40-6356 |

| Nadir CD4 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 205 |

| Range | 7-780 |

| Plasma HIV-RNA, copies/mL | |

| No. of patients with HIV-RNA less than 50 | 16/63 |

| In patients with HIV-RNA more than 50 | |

| Median | 63950 |

| Range | 599-3281900 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | 33 (HAART in 31) |

| Characteristics . | No. . |

|---|---|

| No. of patients | 63 |

| Sex, no. M/F | 56/7 |

| Median age, y (range) | 40 (20-57) |

| HIV transmission, no. | |

| Homosexual | 38 |

| Heterosexual | 13 |

| IV drug user | 10 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| CD4 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 239 |

| Range | 16-1188 |

| No. less than 100 | 13/63 |

| CD8 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 1074 |

| Range | 40-6356 |

| Nadir CD4 cell count, × 106/L | |

| Median | 205 |

| Range | 7-780 |

| Plasma HIV-RNA, copies/mL | |

| No. of patients with HIV-RNA less than 50 | 16/63 |

| In patients with HIV-RNA more than 50 | |

| Median | 63950 |

| Range | 599-3281900 |

| Antiretroviral therapy | 33 (HAART in 31) |

Tumor characteristics

Thirty-eight tumors were classified as classical Burkitt, 21 as BLL, and 4 as BLP. Cytogenetic study could be obtained in 24 cases. An Ig-myc translocation was present in all: t(8;14) in 21, t(8;22) in 2, and t(2;8) in 1. In 13 cases, Ig-myc translocation was isolated, whereas in the 11 other cases, it was associated with other cytogenetic abnormalities without recurrence. One patient was diagnosed simultaneously with Hodgkin lymphoma. All patients had St Jude/Murphy stage IV disease. Extranodal involvement included BM in 50 patients (80%), with BM blasts more than 25% in 48 (76%), and peripheral blasts cells in 17 (21%), CNS in 48 (76%), with CSF leukemia in 12 (19%). The other sites involved are summarized in Table 3. “B” symptoms were present in 51 patients (81%), and a bulky tumor was noted in 19 (30%). The serum LDH level was normal in only 3 patients and more than a 5-fold increase in 28 (44.5%). Poor performance status (ECOG = 3, 4) was observed in 39 patients (62%). As expected, high-risk IPI (> 3) was present in most patients (n = 43).

Baseline tumor characteristics

| Characteristic . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total | 63 (100) |

| Stage IV St Jude/Murphy | 63 (100) |

| Karyotype | 24 (38) |

| t(8;14) | 22 (88) |

| t(8;22) | 2 (8) |

| t(2;8) | 1 (4) |

| Ig-myc only | 13 (54) |

| Hyperploid | 3 (12) |

| “B” symptoms | 51 (81) |

| ECOG | |

| 2 or less | 24 (38) |

| More than 2 | 39 (62) |

| LDH less than normal range (N) | 3 (5) |

| 2 to 5N | 32 (51) |

| More than 5N | 28 (44) |

| Bulky tumor | 19 (30) |

| Peripheral blasts | 17 (27) |

| BM blasts | 50 (79) |

| BM blasts more than 25% | 48 (76) |

| CNS* | 48 (76) |

| CSF leukemia | 12 (19) |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 36 (57) |

| Epidural mass | 10 (16) |

| BM and CNS disease | 37 (59) |

| Liver | 28 (44) |

| GI tract | 19 (30) |

| Kidney | 10 (16) |

| Patients with other sites | 28 (44) |

| IPI | |

| 2 | 6 (9) |

| 3 | 13 (21) |

| 4 | 42 (67) |

| 5 | 2 (3) |

| Characteristic . | No. (%) . |

|---|---|

| Total | 63 (100) |

| Stage IV St Jude/Murphy | 63 (100) |

| Karyotype | 24 (38) |

| t(8;14) | 22 (88) |

| t(8;22) | 2 (8) |

| t(2;8) | 1 (4) |

| Ig-myc only | 13 (54) |

| Hyperploid | 3 (12) |

| “B” symptoms | 51 (81) |

| ECOG | |

| 2 or less | 24 (38) |

| More than 2 | 39 (62) |

| LDH less than normal range (N) | 3 (5) |

| 2 to 5N | 32 (51) |

| More than 5N | 28 (44) |

| Bulky tumor | 19 (30) |

| Peripheral blasts | 17 (27) |

| BM blasts | 50 (79) |

| BM blasts more than 25% | 48 (76) |

| CNS* | 48 (76) |

| CSF leukemia | 12 (19) |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 36 (57) |

| Epidural mass | 10 (16) |

| BM and CNS disease | 37 (59) |

| Liver | 28 (44) |

| GI tract | 19 (30) |

| Kidney | 10 (16) |

| Patients with other sites | 28 (44) |

| IPI | |

| 2 | 6 (9) |

| 3 | 13 (21) |

| 4 | 42 (67) |

| 5 | 2 (3) |

GI indicates gastrointestinal.

Some patients had several neurologic involvements.

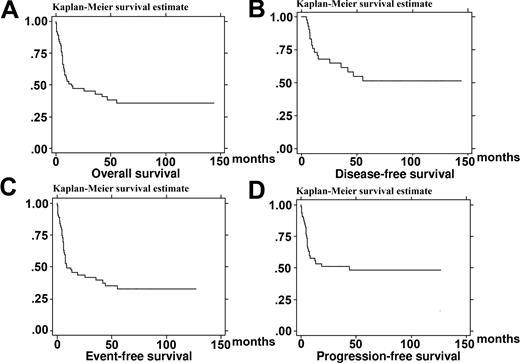

Response to treatment and survival

Forty-four patients (70%) achieved CR. With a median follow-up of 66 months (range, 6-165 months), 11 of them had relapsed with a median time of 7 months (range, 3-44 months). Only 3 patients relapsed after one year of follow-up at months 13, 19, and 44. Two of them achieved CR2, in opposition to none of the patients with early relapse. On July 21, 2006, 26 patients were alive and in CR, 19 of them for more than 2 years, and 37 patients have died. The estimate OS was 47.1% (95% CI, 34-59.1) at 2 years and 38.1% (95% CI, 25.3-50.8) at 4 years (Figure 1A). The median OS was 14.2 months. Causes of death were disease progression in 20 patients, treatment-related toxicity in 7, AIDS-related complications in 5, and other cause in 5. The estimate EFS, PFS, and DFS were 44% (95% CI, 31-56), 51% (95% CI, 37-63), and 67.8% (95% CI, 51-80) at 2 years, respectively, and 35% (95% CI, 23-47), 48% (95% CI, 34-61), and 55% (95% CI, 37.4-69.5) at 4 years, respectively (Figure 1). None of the 19 patients who did not reach CR were alive at 2 years.

Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimate of survival. (A) Overall survival (n = 63). (B) Disease-free survival (n = 44). (C) Event-free survival (n = 63). (D) Progression-free survival (n = 63).

Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimate of survival. (A) Overall survival (n = 63). (B) Disease-free survival (n = 44). (C) Event-free survival (n = 63). (D) Progression-free survival (n = 63).

Treatment toxicity

One patient died of tumor lysis syndrome 24 hours after the cytoreductive phase. Sixty-two patients received the first COPADM course. Forty-eight of them completed the 4 courses of the induction and consolidation phases. Fifteen of the 44 patients who achieved CR had received the full sequence of the LMB regimen. Twenty-nine had received a shortened maintenance for progressive disease in 6 patients and for severe drug-induced BM failure in the 23 others (after one cycle in 6, 2 cycles in 10, and 3 cycles in 7). Indeed, BM toxicity was the major limiting toxicity of this regimen as most patients experienced severe neutropenia and thrombocytopenia during the induction and consolidation phases (Table 4).

Tolerance of the induction and consolidation courses

| . | Cycle . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPADM . | CYVE . | |||

| 1 . | 2 . | 1 . | 2 . | |

| Patients, no. | 62 | 56 | 52 | 48 |

| Fever, no. (%) | 52 (83) | 43 (76) | 47 (90) | 37 (77) |

| Patients with nadir neutrophil count less than 0.5 ×109/L, no. (%) | 59 (95) | 53 (94) | 50 (96) | 46 (96) |

| Patients with nadir platelet count less than 50 ×109/L, no.(%) | 49 (79) | 38 (68) | 50 (96) | 48 (100) |

| No. of hospitalization days, median (range) | 22 (6-43) | 18 (5-32) | 16 (5-34) | 15 (5-30) |

| MTX dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | 46 (74) | 50 (89) | — | — |

| Adriamycin dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | 58 (93.5) | 53 (94) | — | — |

| ARA-C dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | — | — | 41 (79) | 32 (66) |

| Reason for stopping treatment* | ||||

| Progressive disease† | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Toxicity or death‡ | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | ||||

| BL related | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment related | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| . | Cycle . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPADM . | CYVE . | |||

| 1 . | 2 . | 1 . | 2 . | |

| Patients, no. | 62 | 56 | 52 | 48 |

| Fever, no. (%) | 52 (83) | 43 (76) | 47 (90) | 37 (77) |

| Patients with nadir neutrophil count less than 0.5 ×109/L, no. (%) | 59 (95) | 53 (94) | 50 (96) | 46 (96) |

| Patients with nadir platelet count less than 50 ×109/L, no.(%) | 49 (79) | 38 (68) | 50 (96) | 48 (100) |

| No. of hospitalization days, median (range) | 22 (6-43) | 18 (5-32) | 16 (5-34) | 15 (5-30) |

| MTX dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | 46 (74) | 50 (89) | — | — |

| Adriamycin dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | 58 (93.5) | 53 (94) | — | — |

| ARA-C dosage more than 75% theoretical, no. (%) | — | — | 41 (79) | 32 (66) |

| Reason for stopping treatment* | ||||

| Progressive disease† | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Toxicity or death‡ | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Death | ||||

| BL related | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment related | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

— indicates not applicable.

Treatment was stopped after the chemotherapy course.

Designed only progressive BL in alive patients.

Whatever cause of death.

Thirty-eight nonopportunistic major infectious complications occurred in 308 chemotherapy courses, making a rate of 12.4% of severe infectious events per course. It included the following: bacterial septicemia (n = 19 in 18 patients), bacterial pneumonia (n = 9), Pseudomonas cellulitis (n = 3), aspergillosis (n = 3), systemic candidiasis (n = 1), herpes simplex meningitis (n = 2), and hepatitis B reactivation (n = 1). Seven deaths were associated with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. These events were reported equally during induction or consolidation phase, but life-threatening infections occurred more likely during COPADM1 (Table 4).

Ten patients developed one or several AIDS-associated opportunistic infections (OIs) during chemotherapy, including 2 at BL diagnosis, despite HAART in 9 of them: cytomegalovirus (CMV) in 8 (retinitis, n = 2; colitis, n = 1; asymptomatic viremia, n = 5), Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (n = 2), oesophagal candidiasis (n = 2), cryptosporidiosis (n = 1), and tuberculosis (n = 1). The rate of OI was 4.5% per chemotherapy course. With exception of baseline OI and the case of cryptosporidiosis, OI occurred during consolidation or maintenance phase. Three of these patients had experienced previous nonopportunistic infectious complications. In this group, 2 patients with uncontrolled HIV infection died with OI (1 in CR, 1 with progressive BL). Chemotherapy in association with HAART could be resumed in the others and 6 could reach CR.

Three patients experienced high-grade MTX toxicity with acute renal failure (n = 2) and meningitis (n = 1). Chemotherapy dosage has been reduced in some patients because of initial poor performance status or organ failure. However, most patients received the initial planned chemotherapy schedule (Table 4).

Postchemotherapy evolution of HIV infection

Two months after the final chemotherapy course, 33 of the 44 patients in CR had available plasma HIV viral load: 24 had plasma HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL. CD4 cell count was available in 12 of them: the median was 190 × 106/L (range, 5-896 × 106/L) versus 449 × 106/L (range, 162-778 × 106/L) at diagnosis.

During the 12-month postchemotherapy period, 6 patients with uncontrolled HIV replication developed at least one AIDS-related complication: CMV disease in 4; Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, Toxoplasma encephalitis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, and Mycobacterium avium disseminated disease in 1 each. Four of these 6 patients were included before HAART was available, 1 other refused antiretroviral therapy, and the last one had multiresistant HIV infection for years. Three of them died of AIDS conditions. One other patient developed CMV retinitis early after completion of chemotherapy despite plasma HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL on HAART. Improvement was obtained with ganciclovir and prompt immune reconstitution allowed withdrawal of secondary prophylaxis.

Fifty patients began or maintained HAART after COPADM1. In the post-HAART era, only 6 of 53 patients have not been treated with HAART. Four of them have died of progressive BL or sepsis during COPADM1, before the planned date for antiretroviral therapy introduction. The 2 others refused HAART. One died of CMV disease during maintenance phase and the other of relapsing BL at 6 months.

After consolidation phase, plasma HIV RNA was available for 32 patients on HAART and 5 patients without: 28 had plasma HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL. Considering that 3 pre-HAART patients without available plasma HIV RNA had uncontrolled HIV infection, 28 patients had effective control of HIV replication, whereas 12 had not. Only one patient (3.5%) of the first group developed OI in the 12 months after chemotherapy contrasting with 4 (30%) of the 12 patients with uncontrolled HIV replication.

Prognostic analysis

Using the univariate analysis, 6 baseline covariates were prognostic for survival with a P < .05 (Table 5). A CD4 cell count lower than 200 × 106/L, nadir CD4 cell count lower than 100 × 106/L, CD8 cell count lower than 1500 × 106/L, ALC lower than 1000 × 106/L, IPI more than 3, and ECOG score more than 2 were associated with shorter survival. Two other covariates had a tendency (P < .1) to be associated with poor survival: plasma HIV viral load more than 50 copies/mL and “B” symptoms. In the multivariate analysis taking the 8 baseline prognostic covariates into account, only a CD4 cell count of 200 × 106/L or lower and an ECOG more than 2 were independently associated with poor prognosis (Table 5). The strongest good prognosis factor appeared to be performance status: the 4-year probability of survival for patients with an ECOG of 2 or less was 65%.

Results of univariate and multivariate analysis of survival at 2 years

| Covariate . | No. . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P* . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P* . | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Younger than 30 y | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 30 to 39 y | 26 | 0.47 | 0.16-1.32 | .15 | — | — | — |

| 40 to 49 y | 24 | 0.46 | 0.16-1.33 | .15 | — | — | — |

| 50 y or older | 8 | 1.24 | 0.37-4.1 | .7 | — | — | — |

| CD4 cell count | |||||||

| Higher than 500 × 106/L | 15 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 201 to 500 × 106/L | 26 | 1.31 | 0.5-3.42 | .5 | — | — | — |

| 200 × 106/L or lower | 22 | 3.4 | 1.33-8.7 | .01 | 2.84 | 1.09-7.36 | .032 |

| CD8 cell count | |||||||

| 1500 × 106/L or lower | 39 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Higher than 1500 × 106/L | 21 | 2.8 | 1.22-6.4 | .015 | 1.5 | 0.59-3.81 | .38 |

| History of AIDS | |||||||

| No | 50 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 13 | 1.3 | 0.59-2.8 | .5 | — | — | — |

| HAART at entry | |||||||

| Yes | 31 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| No | 32 | 1.02 | 0.55-1.96 | .95 | — | — | — |

| Nadir CD4 cell count | |||||||

| Higher than 100 × 106/L | 37 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 100 × 106/L or lower | 18 | 2.03 | 1.01-4.05 | .044 | 1.69 | 0.75-3.82 | .19 |

| Plasma HIV RNA | |||||||

| More than 50 copies/mL | 44 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Less than 50 copies/mL | 16 | 0.53 | 0.26-1.06 | .075 | 1.13 | 0.42-3.04 | .8 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | |||||||

| More than 1000 × 106/L | 53 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1000 × 106/L or less | 10 | 3.16 | 1.47-6.76 | .003 | 1.34 | 0.46-3.86 | .58 |

| ECOG | |||||||

| 0, 1, 2 | 24 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than 2 | 39 | 3.05 | 1.43-6.49 | .004 | 2.58 | 1.18-5.62 | .017 |

| “B” symptoms | |||||||

| No | 12 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 51 | 2.8 | 0.99-7.97 | .051 | 1.18 | 0.47-6.97 | .38 |

| Bulky disease | |||||||

| No | 43 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 19 | 1.63 | 0.82-3.22 | .16 | — | — | — |

| LDH levels | |||||||

| Normal value (N) or lower | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than N to 5N or less | 32 | 1.87 | 0.25-14.06 | .54 | — | — | — |

| More than 5N | 28 | 2.91 | 0.38-21.76 | .3 | — | — | — |

| Histologic subtype | |||||||

| Classical BL | 38 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| BLL or BLP | 25 | 1.31 | 0.68-2.52 | .4 | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetic study | |||||||

| Ig-myc only | 13 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Complex | 11 | 2.5 | 0.79-8.08 | .116 | — | — | — |

| Peripheral blasts | |||||||

| No | 46 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 17 | 1.35 | 0.66-2.7 | .4 | — | — | — |

| CSF leukemia | |||||||

| No | 51 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 12 | 0.99 | 0.43-2.26 | .98 | — | — | — |

| Cranial nerve palsy or spinal cord injury | |||||||

| No | 30 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 18 | 1.14 | 0.52-2.5 | .72 | — | — | — |

| Hemoglobin level | |||||||

| Higher than 10 g/L | 270 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10 g/dL or lower | 360 | 14 | 7.6-27.8 | .25 | — | — | — |

| Platelet level | |||||||

| More than 100 × 109/L | 45 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 100 × 109/L or less | 18 | 1.63 | 0.83-3.2 | .15 | — | — | — |

| IPI | |||||||

| 0,1,2,3 | 19 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than 3 | 44 | 2.23 | 1.01-4.89 | .045 | 0.49 | 0.12-2.03 | .33 |

| MTX at COPADM1 | |||||||

| Dosage higher than 75% | 44 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Dosage 75% or lower | 18 | 1.69 | 0.84-3.33 | .14 | — | — | — |

| Covariate . | No. . | Univariate analysis . | Multivariate analysis . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P* . | Hazard ratio . | 95% confidence interval . | P* . | ||

| Age | |||||||

| Younger than 30 y | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 30 to 39 y | 26 | 0.47 | 0.16-1.32 | .15 | — | — | — |

| 40 to 49 y | 24 | 0.46 | 0.16-1.33 | .15 | — | — | — |

| 50 y or older | 8 | 1.24 | 0.37-4.1 | .7 | — | — | — |

| CD4 cell count | |||||||

| Higher than 500 × 106/L | 15 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 201 to 500 × 106/L | 26 | 1.31 | 0.5-3.42 | .5 | — | — | — |

| 200 × 106/L or lower | 22 | 3.4 | 1.33-8.7 | .01 | 2.84 | 1.09-7.36 | .032 |

| CD8 cell count | |||||||

| 1500 × 106/L or lower | 39 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Higher than 1500 × 106/L | 21 | 2.8 | 1.22-6.4 | .015 | 1.5 | 0.59-3.81 | .38 |

| History of AIDS | |||||||

| No | 50 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 13 | 1.3 | 0.59-2.8 | .5 | — | — | — |

| HAART at entry | |||||||

| Yes | 31 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| No | 32 | 1.02 | 0.55-1.96 | .95 | — | — | — |

| Nadir CD4 cell count | |||||||

| Higher than 100 × 106/L | 37 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 100 × 106/L or lower | 18 | 2.03 | 1.01-4.05 | .044 | 1.69 | 0.75-3.82 | .19 |

| Plasma HIV RNA | |||||||

| More than 50 copies/mL | 44 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Less than 50 copies/mL | 16 | 0.53 | 0.26-1.06 | .075 | 1.13 | 0.42-3.04 | .8 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count | |||||||

| More than 1000 × 106/L | 53 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 1000 × 106/L or less | 10 | 3.16 | 1.47-6.76 | .003 | 1.34 | 0.46-3.86 | .58 |

| ECOG | |||||||

| 0, 1, 2 | 24 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than 2 | 39 | 3.05 | 1.43-6.49 | .004 | 2.58 | 1.18-5.62 | .017 |

| “B” symptoms | |||||||

| No | 12 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 51 | 2.8 | 0.99-7.97 | .051 | 1.18 | 0.47-6.97 | .38 |

| Bulky disease | |||||||

| No | 43 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 19 | 1.63 | 0.82-3.22 | .16 | — | — | — |

| LDH levels | |||||||

| Normal value (N) or lower | 3 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than N to 5N or less | 32 | 1.87 | 0.25-14.06 | .54 | — | — | — |

| More than 5N | 28 | 2.91 | 0.38-21.76 | .3 | — | — | — |

| Histologic subtype | |||||||

| Classical BL | 38 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| BLL or BLP | 25 | 1.31 | 0.68-2.52 | .4 | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetic study | |||||||

| Ig-myc only | 13 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Complex | 11 | 2.5 | 0.79-8.08 | .116 | — | — | — |

| Peripheral blasts | |||||||

| No | 46 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 17 | 1.35 | 0.66-2.7 | .4 | — | — | — |

| CSF leukemia | |||||||

| No | 51 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 12 | 0.99 | 0.43-2.26 | .98 | — | — | — |

| Cranial nerve palsy or spinal cord injury | |||||||

| No | 30 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 18 | 1.14 | 0.52-2.5 | .72 | — | — | — |

| Hemoglobin level | |||||||

| Higher than 10 g/L | 270 | 10 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10 g/dL or lower | 360 | 14 | 7.6-27.8 | .25 | — | — | — |

| Platelet level | |||||||

| More than 100 × 109/L | 45 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 100 × 109/L or less | 18 | 1.63 | 0.83-3.2 | .15 | — | — | — |

| IPI | |||||||

| 0,1,2,3 | 19 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| More than 3 | 44 | 2.23 | 1.01-4.89 | .045 | 0.49 | 0.12-2.03 | .33 |

| MTX at COPADM1 | |||||||

| Dosage higher than 75% | 44 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Dosage 75% or lower | 18 | 1.69 | 0.84-3.33 | .14 | — | — | — |

— indicates not applicable; HAART, indicates highly active antiretroviral therapy; Ig-myc, t(8;14), t(8;22) or t(2;8); CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; and MTX, methotrexate.

Likelihood ratio test.

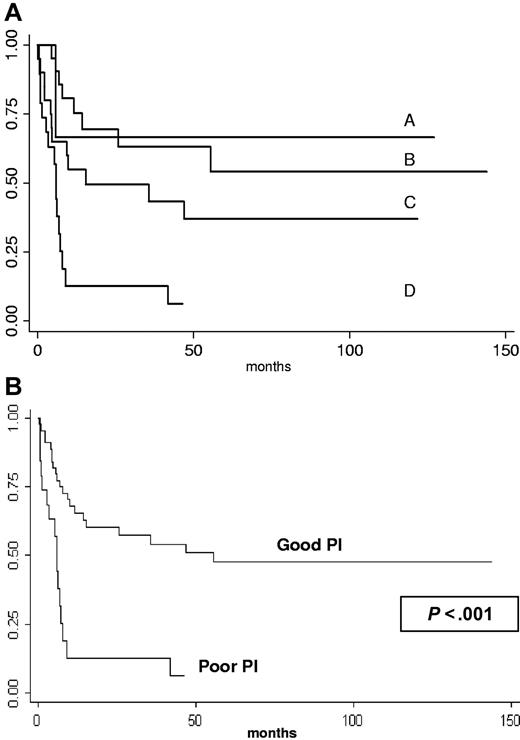

The 2-year probability of survival for patients with ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count higher than 200 × 106/L (n = 21); ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 3); ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count higher than 200 × 106/L (n = 20); ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 19) was 69.5% (95% CI, 44-85); 66.7% (95% CI, 54-94.5); 49.5% (95% CI, 26.5-70); and 12.6% (95% CI, 2-32.9), respectively (Figure 2A). Survival of patients with 0 or 1 factor (good prognosis group, n = 44) was 60.2% (95% CI, 43.9-73.1) and 51% (95% CI, 34.4-65.3) at 2 and 4 years, respectively. In contrast, the 2-year probability of survival for the 19 patients with 2 factors (poor prognosis group) was only 12.6% (95% CI, 8.3-32.9) (log-rank test P < .001, Figure 2B).

Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimate of survival according to prognosis factors (CD4 cell count ≤ 200 × 106/L, ECOG > 2). (A) A indicates ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 3); B, ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count higher than 200 × 106/L (n = 21); C, ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count more than 200 × 106/L (n = 20); and D, ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 19). (B) According to prognosis index (PI), good PI = 0 or 1 factor (n = 44); poor PI = 2 factors (n = 19).

Kaplan-Meier product-limit estimate of survival according to prognosis factors (CD4 cell count ≤ 200 × 106/L, ECOG > 2). (A) A indicates ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 3); B, ECOG of 2 or less and CD4 count higher than 200 × 106/L (n = 21); C, ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count more than 200 × 106/L (n = 20); and D, ECOG more than 2 and CD4 count of 200 × 106/L or lower (n = 19). (B) According to prognosis index (PI), good PI = 0 or 1 factor (n = 44); poor PI = 2 factors (n = 19).

Discussion

Despite introduction of HAART, prognosis of AIDS-related BL is still poor when treated with standard-dose chemotherapy.37 In the context of HIV infection, recent small trials have shown interesting results with short duration but intensive multiagent chemotherapy such as the hyper-CVAD41 or the CODOX-M/IVAC regimen.42 We present the result of a prospective clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of the LMB86 regimen in a large cohort of HIV-related BL with CNS involvement and/or leukemia. The clinical characteristics of the patients included in this trial were typical of high-risk BL with a high prevalence of “B” symptoms, poor performance status, and high LDH level. HIV-related BL often occurs in patients with mild immunodeficiency.29 In this series, 41 (65%) had a CD4 cell count higher than 200 × 106/L and 15 (24%), higher than 500 × 106/L. However, 13 (20%) were severely immunocompromised (CD4 count ≤ 100 × 106/L) and already had AIDS manifestations. These results are consistent with published data.29,43

Several conclusions can be drawn from the results of this study and from the long-term (> 5 years) follow-up of these patients. CR could be obtained in 70% (n = 44) of patients. These results compare favorably with the only 30% of CR reported in patients treated with CHOP or M-BACOD (methotrexate, bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dexamethasone).37 Furthermore, this is not much lower than the 80% CR obtained with LMB protocol in HIV-negative patients with stage IV BL.12 This confirms the good preliminary results of CODOX-M and hyper-CVAD in HIV BL.41,42 As expected, the achievement of CR after the initial chemotherapy phase was crucial for prolonged survival, as none of the 19 patients who did not obtain CR were alive at 2 years. The role of the maintenance phase appeared more uncertain as only 4 of the 23 patients for whom this phase was shortened because of cumulative BM toxicity had relapsed.

The 2-year OS was 47% versus 67% in HIV-negative stage IV patients with BL treated with the same regimen,12 and the 4-year OS was 37%. As in nonimmunocompromised patients, a high initial mortality associated with treatment toxicity, failure, or early progression of disease occurred during the first year of follow-up. Nevertheless, the pattern of survival plot is atypical for BL2,3 with a delayed plateau. Indeed, we observed late events and deaths in opposition to what was observed in HIV-negative patients with BL and the plateau was not reached before 4 years. In patients in CR, most deaths (50%) were caused by relapsing BL. Eleven relapses occurred making a relapse rate of 25%. Eight occurred in the first year of follow-up and 1 at month 13. All these patients with early relapse died of BL. One relapsed at 18 months and was still alive in CR2 7 years after. The later relapse (month 44) was more likely the occurrence of a second lymphoma exhibiting immunoblastic morphology and phenotype. However, molecular study was not available and this case counted as having relapsed. The patient died in CR2 during salvage therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation. In immunocompetent patients treated with LMB, CODOX-M/IVAC, or hyper-CVAD, relapse rate ranged from 7% to 34%.5,6,11,12 Late overmortality may have explanations other than more frequent delayed relapse. Five patients in CR died of AIDS. Three of them received HAART during chemotherapy. However, only one had controlled HIV infection at the end of chemotherapy and none at the time of AIDS complication. The other causes of death in patients in CR were treatment related in 1 (aspergillosis during first maintenance course), second cancer in 1, Listeria monocytogenes meningitis in 1, and suicide in 1. Overall, 9 deaths (24%) were not due to BL or its treatment and occurred in a median time of 25 months (range, 5-55 months), emphasizing that overmortality may be due to specific factors in this population.

One potential limitation to intensive chemotherapy in this immunocompromised population is treatment toxicity. Treatment-related death is an hallmark of those intensive regimens even in the general adult population.6,7,12 This regimen was responsible for severe BM toxicity in almost all patients (Table 4). Seven treatment-associated deaths occurred during the induction phase of the therapy. All were secondary to neutropenia-related sepsis. Of note, most of these patients had poor performance status and all but one were severely immunocompromised.

The multivariate analysis confirmed the poor prognosis associated with severe immune deficiency and ECOG. Patients with good performance status (ECOG ≤ 2) had a good outcome as 70% were alive at 2 years. As expected in ARL,30,35,36 a CD4 cell count lower than 200 × 106/L was associated with poor outcome. Combining these 2 factors, we provide a prognosis index to define a patient subset with a clear benefit in survival when treated with LMB regimen. The 4-year estimate survival in the good prognosis group was 51% and favorably compared with the 15% observed in HIV BL treated with CHOP regimen.37 In this patient subset, toxicity seems acceptable with regard to improvement of overall survival. In the poor prognosis group (2 factors), there was no evidence of prolonged survival. The improvement of survival in such immunocompromised patients with poor performance status is challenging. More intensive chemotherapy regimen is probably not a good option as most treatment-related deaths were in this group of patients. Less intensive induction phase may reduce CR rate, which is the key to cure such disseminated BL. Addition of rituximab to a less intensive LMB-adapted regimen (as the first sequence CODOX-M/IVAC) may be an interesting alternative as its association to hyper-CVAD improves CR rate and OS in adult BL.44 Nevertheless, the association of rituximab to chemotherapy in the context of AIDS is controversial. Some studies found an improvement in OS,45 but a randomized trial had revealed an infection-related overmortality that cancelled the benefit in survival for ARL.46 Furthermore, some AIDS-related BLs have plasmacytoid differentiation with loss of CD20.38,47 Adjunction of rituximab to intensive chemotherapy in AIDS BL should be evaluated in prospective studies.

In these patients, HAART at entry had no impact on survival. This could be explained by the fact that only 3 of 32 deaths that occurred in the first 2 years of follow-up were related to an AIDS complication. Almost all deaths that occurred during this period of follow-up were associated with treatment failure or complication. Of note, 7 patients were treated before 1996; 5 of them were in CR after consolidation phase, suggesting that HAART has probably only slight effect on treatment response and that chemotherapy intensity is probably pivotal to cure this particular type of ARL. Three of these 5 patients died: 1 of AIDS related cachexia at 3 years, 1 of relapsing BL at 10 months, and the last of other cause at 7 months. The 2 others have been treated with HAART since it was available and were still alive and free of disease at 8 and 9 years. Nevertheless, real impact of HAART is difficult to appreciate because most patients received antiretroviral therapy during chemotherapy with a possible improvement of chemotherapy tolerance.32 Patients receiving HAART during chemotherapy (ongoing HAART) were more likely to survive (P = .01, data not shown), but in the post-HAART era, the major limiting factor to introduce antiretroviral therapy was an early death occurring during the first chemotherapy course, before the planned date for HAART introduction. This is a major bias to correctly interpret the impact of ongoing HAART. Of note, in the 37 patients with available plasma HIV RNA at the end of consolidation phase, 72% of the patients with controlled HIV replication were still alive at last follow-up contrasting with only 28% of the patients with persistent HIV replication. This difference does not reach significance (P = .07, data not shown), which may be related to the small size of the group with uncontrolled HIV infection at this point (n = 9). Late deaths (after 2 years) were observed only in the group with persistent high HIV viral load. Finally, none of the 5 patients who died of AIDS had a controlled HIV infection at the time of fatal AIDS complication. These results point to the importance of maintaining efficient antiretroviral therapy in the months and years after BL.

Overall, this study demonstrates that despite poor prognosis reported in the post-HAART era, AIDS-related stage IV BL can be cured. We provide a simple prognosis index based on ECOG and CD4 cell count to define a patient subset (with CD4 count > 200 × 106/L and/or ECOG ≤ 2) for whom intensive combination chemotherapy including high-dose MTX should be proposed. Prolonged survival probably depends on the control of HIV infection and on subsequent immune restoration. This last point justifies the maintenance or the early introduction of an effective antiretroviral therapy.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: E.O. designed the study; L. Galicier, C.F., and R.B. performed the study; L. Galicier, and C.F. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; L. Gérard did all statistical analysis; M.-T.D. and V.M. reviewed cytologic and histologic samples; all authors checked the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Lionel Galicier, Immunopathologie Clinique, Hôpital Saint Louis, 1 Avenue Claude Vellefaux, 75010 Paris, France; e-mail: lionel.galicier@sls.aphp.fr.