In human β-thalassemia, the imbalance between α- and non–α-globin chains causes ineffective erythropoiesis, hemolysis, and anemia: this condition is effectively treated by an enhanced level of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). In spite of extensive studies on pharmacologic induction of HbF synthesis, clinical trials based on HbF reactivation in β-thalassemia produced inconsistent results. Here, we investigated the in vitro response of β-thalassemic erythroid progenitors to kit ligand (KL) in terms of HbF reactivation, stimulation of effective erythropoiesis, and inhibition of apoptosis. In unilineage erythroid cultures of 20 patients with intermedia or major β-thalassemia, addition of KL, alone or combined with dexamethasone (Dex), remarkably stimulated cell proliferation (3-4 logs more than control cultures), while decreasing the percentage of apoptotic and dyserythropoietic cells (<5%). More important, in both thalassemic groups, addition of KL or KL plus Dex induced a marked increase of γ-globin synthesis, thus reaching HbF levels 3-fold higher than in con-trol cultures (eg, from 27% to 75% or 81%, respectively, in β-thalassemia major). These studies indicate that in β-thalassemia, KL, alone or combined with Dex, induces an expansion of effective erythropoiesis and the reactivation of γ-globin genes up to fetal levels and may hence be considered as a potential therapeutic agent for this disease.

Introduction

Human hemoglobin (Hb) is a tetrameric molecule composed of 2 pairs of subunits, encoded by 2 gene clusters. The human α-globin–like genes (ζ, α1, and α2) are on chromosome 16, and the β-globin–like genes (ϵ, Gγ, Aγ, δ, and β) are on chromosome 11. During development, sequential switches take place in both the α- and β-globin–like clusters.1,2 In the perinatal period, the 2 adult hemoglobins (HbA, α2β2, and HbA2, α2δ2) gradually replace fetal hemoglobin (HbF, α2γ2).1 By the age of 1 year, the hemoglobin composition is approximately 97.5% HbA, 2% HbA2, and 0.5% HbF.3 The residual HbF is concentrated in F-cells, which represent less than 5% of red blood cells (RBCs).4

The β-thalassemias are characterized by insufficient or absent production of β-globin chains, due to mutations affecting the β-globin gene complex.5 The disease is caused by the imbalanced α and non–α-globin chain synthesis, which leads to accumulation and precipitation of unpaired α-globin chains and, consequently, to ineffective erythropoiesis and hemolysis.6 Although the relationship between phenotype and genotype in β-thalassemia is complex, the α-nonα ratio correlates with the severity of disease.7 In β-thalassemia intermedia (β-TI), one or 2 β-globin genes are defective, but concurrent genetic factors (hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin [HPFH], α and δβ-thalassemia determinants) can reduce or enhance the globin chain imbalance, thus ameliorating or exacerbating the clinical conditions. In homozygous β0-thalassemia major (β-TM), a very high α-nonα ratio is associated with severe ineffective erythropoiesis and dependence on red blood cell transfusions for survival.

These observations suggest that the severity of the disease can be reduced by γ-globin reactivation. In vitro studies demonstrated that kit ligand (KL) stimulates HbF synthesis in sickle cell anemia8 and normal erythroid progenitors9,10 up to 15% to 20%. Moreover, butyrate analogs,11 hydroxyurea,12 and glucocorticoids13,14 potentiate this stimulatory effect. In addition to its action on HbF synthesis, KL protects erythroid progenitors15,16 and precursors17,18 from apoptosis, at least in part trough Bcl-XL upmodulation.18

On this basis, we have explored HbF expression and the expansion of the erythroid compartment in unilineage erythroid cultures of β-thalassemic hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) isolated from peripheral blood (PB) and supplemented with KL, alone or in combination with dexamethasone (Dex). A marked HbF reactivation up to fetal levels was observed in both β-TI and β-TM patients. More important, this effect was associated with a rise of effective erythropoiesis and an inverse decline of apoptosis and dyserythropoiesis in all analyzed subjects.

Methods

HPC purification

Adult PB (450 mL) was provided by healthy adult male donors after informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Peripheral blood (20-30 mL) of thalassemic patients at Sant'Eugenio Hospital, Rome, Italy was obtained after informed consent, also in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the local ethical Committee of the Sant'Eugenio Hospital.

Blood was collected in preservative-free citrate/phosphate/dextrose/adenine (CPDA-1) anticoagulant. A buffy coat was obtained by centrifugation (Beckman J6M/E; 400g (1400 rpm) for 20 minutes at room temperature; Beckman Instruments, Fullerton, CA). Low-density cells, (less than 1.077 g/mL) were isolated using a Ficoll gradient as previously described.19

The CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) were then purified using a MiniMACS CD34 isolation system (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergish Gladbach, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Purified cells were more than 90% CD34+, as evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

Recombinant human HGFs and chemical inducers

Interleukin-3 (IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage–colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and KL were supplied by Peprotech (London, United Kingdom), erythropoietin (Epo) was purchased from Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA), Dex was provided by Sigma Chemical (St Louis, MO).

HPC unilineage erythroid culture

Mini-bulk culture.

Purified HPCs from normal and thalassemic PB were grown in fetal calf serum (FCS)–free liquid suspension cultures (5 × 104 cells/mL per well) in a fully humidified 5% CO2/5% O2/90% N2 atmosphere and selectively induced to unilineage erythroid differentiation by an appropriate HGF cocktail (saturating EPO levels and low dosages of IL-3 and GM-CSF) as previously reported.20,21 This culture condition, defined in the text as erythroid control culture, was supplemented or not with KL (from 1 to 100 ng/mL) alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M).

Morphologic analysis.

Cells (2 × 104) were harvested at different days of culture (from day 8 to terminal differentiation), smeared on a glass slide by cytospin centrifugation, and stained with standard May-Grünwald Giemsa.

Evaluation of apoptosis: annexin V binding assay

Apoptosis in unilineage erythroid cultured cells was evaluated by double staining with fluorescein-isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled annexinV and propidium iodide (PI). Briefly, 2 × 104 cells were washed twice in cold PBS and resuspended in 0.25 mL of binding buffer (HEPES [N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid]–buffered saline solution supplemented with CaCl2). Five microliters FITC-annexin V and 5 μL PI reagents were added to the cells, and the mixture were gently vortexed and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. Within 1 hour, the cells were analyzed at 488 nm in a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA).

Hb content

Total Hb content was evaluated in aliquots of 106 mature erythroid cells by an improved cyanohemoglobin method (Quantichrom Hemoglobin Assay Kit; Gentaur, Brussels, Belgium). The results were expressed as mean corpuscolar hemoglobin (MCH), pg/red cell.

HbF assays

The HbF assay (γ-chain content and biosynthesis) was carried out at terminal erythroid maturation (days 14-16 for control and days 22-26 for KL or KL ± Dex cultures, respectively).

γ-chain content.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation of globin chains was performed according to previously published method.22 Briefly, cell lysates from bulk culture were separated on a chromatographic column (Merck LiChrospher 100 CH8/2, 5μm; E. Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) using as eluents a linear gradient of acetonitrile-methanol-0.155 M sodium chloride (eluent A; pH 2.7, 68:4:28 vol/vol/vol) and acetonitrile-methanol-0.077 M sodium chloride (eluent B; pH 2.7, 26:33:41 vol/vol/vol). Gradient was from 20% to 60% eluent A in 60 minutes at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The optimal absorbance of the different globins was evaluated at 214 nm because absorbance coefficients of the different chains are identical at this wavelength.22

This method facilitated the separation of α-, β-, and 3 type of γ-chains (Aγ, Tγ, and Gγ); total γ-globins were determined by adding Gγ and Aγ (which includes Tγ, when present).

γ-chain biosynthesis.

At terminal erythroid maturation, 200 μCi [3H]leucine (Amersham Bioscience Europe, Amersham, United Kingdom) were directly added to each differentiating culture condition in flat-bottomed 24-microwell plates containing 5 × 105cells/mL per well incubated overnight. Cells were then collected, extensively washed, lysed, and separated on a chromatographic column (as described in “γ-chain content”). Single fractions were collected and the radioactivity incorporation in de novo synthesized globin polypeptides was quantified by scintillation counting of the fractions (Beckman Coulter LS5000TD). In β-TI, HbF synthesis was expressed as a percentage of γ-nonα-chain synthesis (ie, γ/[β + γ]), whereas in β-TM it was expressed as γ-α-chain ratio.

Results

In the initial experiments, CD34+ cells, isolated from PB of β-TI and β-TM patients, were grown in unilineage erythroid culture supplemented or not with KL in a dose-response fashion (1, 10, and 100 ng/mL; Figure 1). At a concentration of 10 to 100 ng/mL, KL sharply stimulated erythropoietic proliferation, as indicated by a 2 to 3 log rise of cell output over control values, while delaying terminal differentiation/maturation (ie, presence of > 90% mature erythroblasts) from 15 up to 20 to 25 days of culture (Figure 1 top panel). In terms of HbF level, evaluated by HPLC analysis, the addition of KL at 10 to 100 ng/mL increased the HbF content in late erythroblasts, specifically, from 15% up to 35% to 45%, and from 30% up to 60% to 70% in representative β-TI and β-TM patients, respectively (Figure 1 bottom panel). Based on these results, the following studies were performed at the plateau KL dosage of 100 ng/mL.

KL dose-response in β thalassemic patients. Cell growth (top panels) and HbF content (bottom panels) in minibulk HPC unilineage erythroid cultures derived from a representative β-TI (left panels) and β-TM patient (right panels), supplemented or not with graded amounts of KL (1, 10, or 100 ng/mL). The total cell number is shown in top panels. The percentage of HbF content (evaluated as the γ/[β + γ] and γ/α ratio in β-TI and β-TM, respectively) is reported in bottom panels.

KL dose-response in β thalassemic patients. Cell growth (top panels) and HbF content (bottom panels) in minibulk HPC unilineage erythroid cultures derived from a representative β-TI (left panels) and β-TM patient (right panels), supplemented or not with graded amounts of KL (1, 10, or 100 ng/mL). The total cell number is shown in top panels. The percentage of HbF content (evaluated as the γ/[β + γ] and γ/α ratio in β-TI and β-TM, respectively) is reported in bottom panels.

Proliferation and differentiation/maturation of thalassemic erythroid progenitor cells

We examined 2 groups of β-TI and β-TM patients, with 10 in each group, classified at clinical and laboratory level in terms of genotype, haematologic values, splenectomy, and dependence on red blood cell transfusions (Table 1). As expected, the requirement for transfusions was higher in β-TM than in β-TI patients (Table 1).

Clinical and biological features of β-thalassemic patients

| . | β genotype . | α genotype . | Splenectomy . | Transfusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-TI patients | ||||

| 1 | IVSI-110/IVSI-110 | −α3.7α/αα | yes | <4 wks |

| 2 | β039/δβ ″sicilian type″ | — | yes | no |

| 3 | β039/+22 | — | no | no |

| 4 | IVSI-6/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 5 | β039/β039 | −α3.7α/−α3.7 α | yes | <4 wks |

| 6 | IVSI-6/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 7 | β039 | ααα | yes | >4 wks |

| 8 | β039 | ααα | yes | <4 wks |

| 9 | IVSI-1/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 10 | −87/−87 | — | yes | no |

| β-TM patients | ||||

| 1 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 2 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 3 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 4 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 5 | β039/β039 | — | no | Every 3 wks |

| 6 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 7 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 8 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 9 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 10 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| . | β genotype . | α genotype . | Splenectomy . | Transfusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-TI patients | ||||

| 1 | IVSI-110/IVSI-110 | −α3.7α/αα | yes | <4 wks |

| 2 | β039/δβ ″sicilian type″ | — | yes | no |

| 3 | β039/+22 | — | no | no |

| 4 | IVSI-6/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 5 | β039/β039 | −α3.7α/−α3.7 α | yes | <4 wks |

| 6 | IVSI-6/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 7 | β039 | ααα | yes | >4 wks |

| 8 | β039 | ααα | yes | <4 wks |

| 9 | IVSI-1/IVSI-6 | — | yes | >4 wks |

| 10 | −87/−87 | — | yes | no |

| β-TM patients | ||||

| 1 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 2 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 3 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 4 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 5 | β039/β039 | — | no | Every 3 wks |

| 6 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 7 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 8 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 9 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

| 10 | β039/β039 | — | yes | Every 3 wks |

Hb was 100 to 105 g/L for all patients listed. Either the time interval since the last transfusion or the rate of transfusion is shown in column 5.

— indicates normal α genotype.

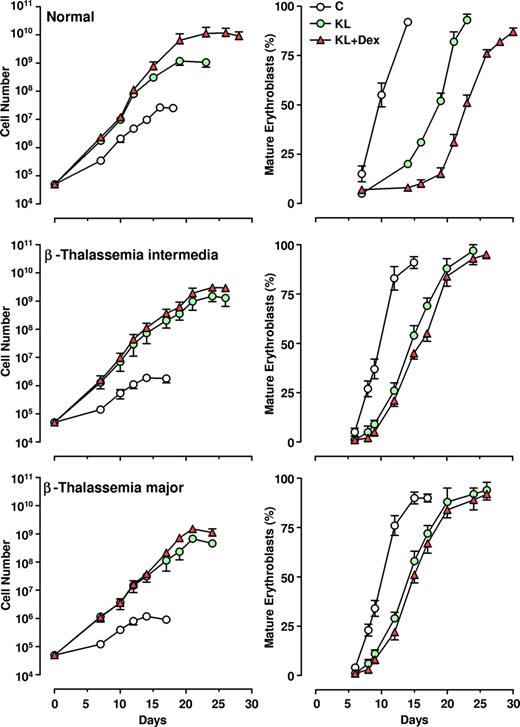

The CD34+ HPCs, isolated from thalassemic patients, were grown in unilineage erythroid cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng/mL), alone or in combination with relatively low doses of Dex (10−8 M). The growth curves (left panels) and the percentage of mature erythroblasts (late polychromatophilic + orthochromatic erythroblasts, right panels) were compared with those monitored in normal HPC culture (Figure 2).

Effect of KL with and without Dex on erythroid cell growth and maturation. Left panels: growth curve from minibulk HPC erythroid cultures obtained from 10 healthy adults, 10 β-TI, and 10 β-TM PB patients supplemented or not with KL (100 ng/mL) or KL (100 ng/mL) plus Dex (10−8 M). Total cell number (mean ± SEM) starting from initial 5×104 CD34+ cells/mL is shown. The differences between the normal and β-TI or β-TM control growth curves are highly significant by analysis of variance (P < .001). Right panels: kinetics of erythroid maturation observed in the same minibulk HPC cultures reported in left panels. The percentage (mean ± SEM values) of mature erythroblasts (late polychromatophilic + orthochromatic erythroblasts) is shown.

Effect of KL with and without Dex on erythroid cell growth and maturation. Left panels: growth curve from minibulk HPC erythroid cultures obtained from 10 healthy adults, 10 β-TI, and 10 β-TM PB patients supplemented or not with KL (100 ng/mL) or KL (100 ng/mL) plus Dex (10−8 M). Total cell number (mean ± SEM) starting from initial 5×104 CD34+ cells/mL is shown. The differences between the normal and β-TI or β-TM control growth curves are highly significant by analysis of variance (P < .001). Right panels: kinetics of erythroid maturation observed in the same minibulk HPC cultures reported in left panels. The percentage (mean ± SEM values) of mature erythroblasts (late polychromatophilic + orthochromatic erythroblasts) is shown.

As expected, the erythroid growth curves of β-TI and β-TM cultures reached plateau levels lower than observed for normal ones (1-2 × 106 vs 2.5 × 107 cells, respectively, mean values, generated by 5 × 104 CD34+ cells). Addition of KL, and particularly KL plus Dex, remarkably stimulated erythroid cell proliferation in both β-thalassemia groups (ie, a 3-4 log rise of cell output over KL-untreated culture), thus reaching values similar to those obtained in healthy controls (109 and 1010 cells in KL and KL plus Dex groups, respectively; Figure 2 left panel). Notably, the amplification of erythroid cells in KL plus Dex–supplemented cultures was more elevated than that observed in KL-treated cultures for both healthy controls (P < .001) and thalassemic patients (P < .05).

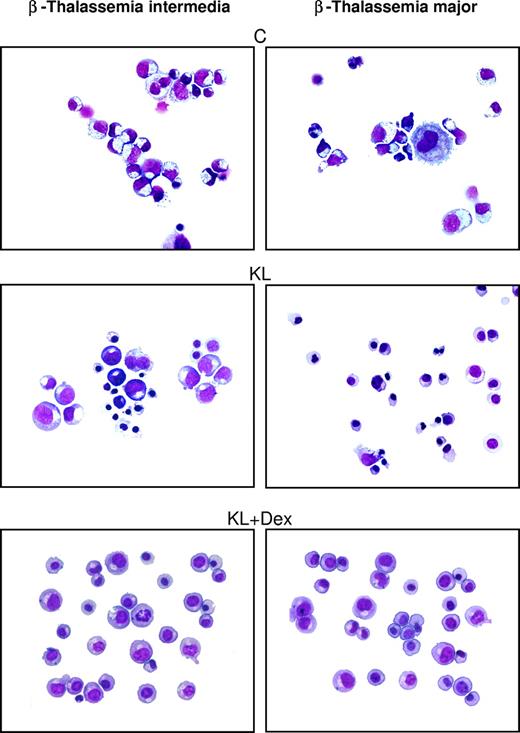

In β-thalassemic control cultures, we observed that (1) a significant number of cells did not reach terminal erythroid maturation, due to dyserythropiesis and apoptosis; (2) the appearance of mature erythroblasts was delayed by 2 to 4 days, compared with healthy cultures; and (3) the mature erythroblasts showed several morphologic abnormalities, including irregular shape, cytoplasmatic vacuolization, and scarce hemoglobinization (Figure 2 right panel and Figure 3). Treatment with KL with or without Dex sharply modified these parameters: specifically, (1) terminal erythroid maturation was delayed up to day 26 to 28 (ie, 1-2 weeks later than in KL-untreated cultures), as observed in healthy controls (Figure 2 right panel); (2) almost all erythroid cells reached terminal maturation; and (3) late erythroblasts did not show any abnormality (Figure 3).

Morphologic cell features in β-thalassemic erythropoiesis. Morphology of erythroid cells generated in HPC unilineage erythroid cultures from one representative β-TI patient (left panels) and one representative β-TM patient (right panels), supplemented or not with KL and KL plus Dex. Cytocentrifuged cells have been stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa and then analyzed by an Eclipse 1000 optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan; 400×/1.30 NA 40× objective). Images were acquired with a Nikon DXM 1200 camera using ACT-1 software (Nikon).

Morphologic cell features in β-thalassemic erythropoiesis. Morphology of erythroid cells generated in HPC unilineage erythroid cultures from one representative β-TI patient (left panels) and one representative β-TM patient (right panels), supplemented or not with KL and KL plus Dex. Cytocentrifuged cells have been stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa and then analyzed by an Eclipse 1000 optical microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan; 400×/1.30 NA 40× objective). Images were acquired with a Nikon DXM 1200 camera using ACT-1 software (Nikon).

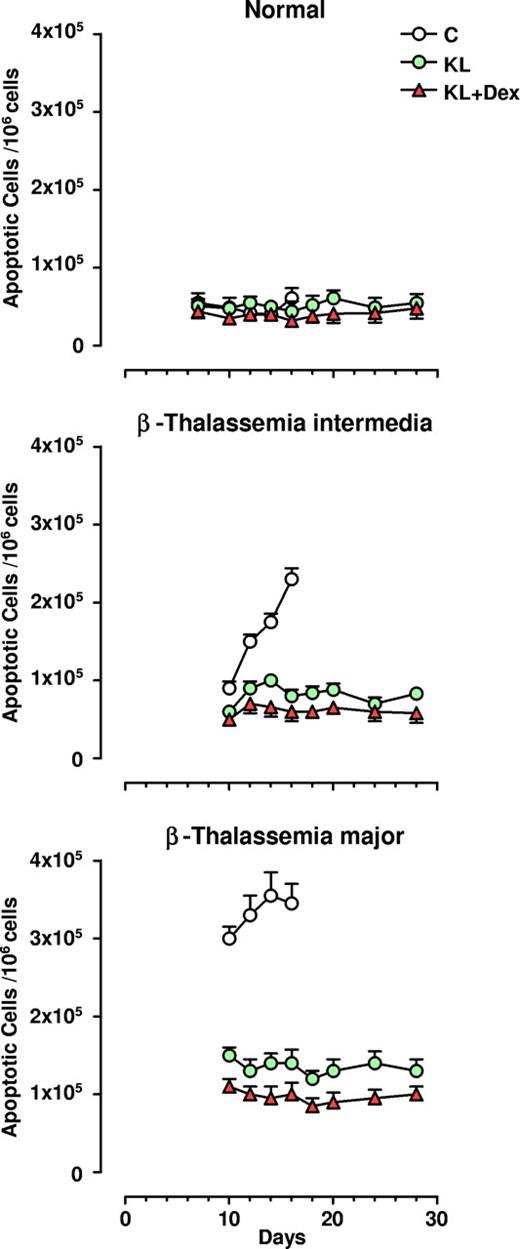

Antiapoptotic effect of KL and KL plus Dex in β-thalassemia erythropoiesis

Apoptosis was monitored during unilineage erythroid differentiation of both β-TI and β-TM progenitor cells: the results were compared with those obtained in healthy controls. At terminal maturation (day 16), 2.3 × 105/106 of total erythroblasts were apoptotic in β-TI cultures, while a higher value (3.5 × 105/106 cells) was observed in the β-TM group. Conversely, healthy controls showed only 0.6 × 105 apoptotic cells/106 total erythro-blasts (Figure 4). Addition of KL, and particularly KL plus Dex, induced a remarkable decrease in apoptotic cells in both types of β-thalassemia, almost down to the values observed in normal cultures (ie, 0.7 and 0.9 × 105/106 total erythroblasts in β-TI and β-TM, respectively; Figure 4 and Figure 5 left panel). Notably, the decrease in the number of apoptotic cells was greater in KL plus Dex than in KL-supplemented cultures (P < .05 for β-TI group; P < .01 for β-TM group).

Antiapoptotic effect of KL with and without Dex in HPC erythroid cultures. Numbers of apoptotic cells/106 erythroblasts evaluated during erythroid differentiation of normal, β-TI, and β-TM HPCs grown in the absence (C) or presence of KL (100 ng/mL), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). At different days erythroid cells were harvested and processed for the evaluation of apoptotic cells using the annexin V binding assay. Mean (± SEM) values from 8 separate experiments carried out on 8 different donors are shown. The differences between the normal and β-TI or β-TM control growth curves are highly significant by analysis of variance (P < .001).

Antiapoptotic effect of KL with and without Dex in HPC erythroid cultures. Numbers of apoptotic cells/106 erythroblasts evaluated during erythroid differentiation of normal, β-TI, and β-TM HPCs grown in the absence (C) or presence of KL (100 ng/mL), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). At different days erythroid cells were harvested and processed for the evaluation of apoptotic cells using the annexin V binding assay. Mean (± SEM) values from 8 separate experiments carried out on 8 different donors are shown. The differences between the normal and β-TI or β-TM control growth curves are highly significant by analysis of variance (P < .001).

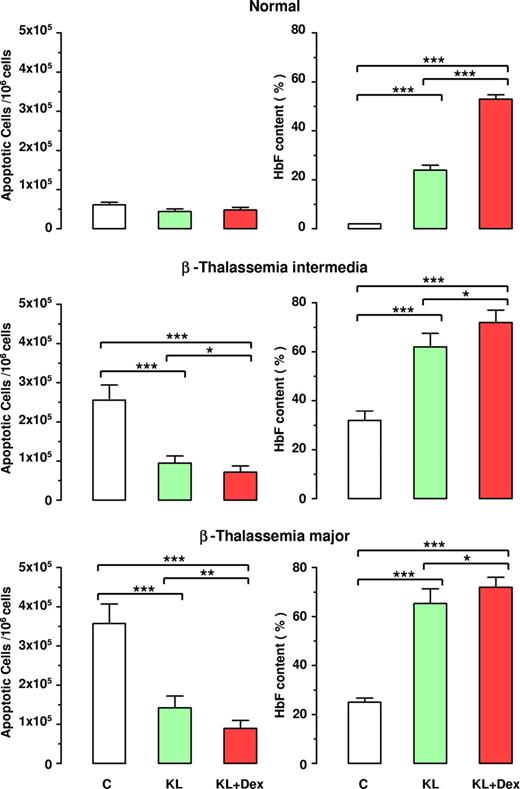

Inverse correlation between apoptosis and HbF reactivation in β thalassemia. Evaluation of apoptotic cells (left panels) and HbF content (right panels) at terminal erythroid differentiation in normal, β-TI, and β-TM HPC cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). Mean (± SEM) values from 7 separate experiments on 7 different donors are reported. Variance analysis was expressed as Bonferroni P values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Inverse correlation between apoptosis and HbF reactivation in β thalassemia. Evaluation of apoptotic cells (left panels) and HbF content (right panels) at terminal erythroid differentiation in normal, β-TI, and β-TM HPC cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). Mean (± SEM) values from 7 separate experiments on 7 different donors are reported. Variance analysis was expressed as Bonferroni P values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Moreover, the antiapoptotic effect of KL with or without Dex was associated with significant increase in HbF production, up to 72% HbF content in both β-TI and β-TM groups treated with KL plus Dex, compared with 52% in healthy controls (Figure 5 right panel).

Reactivation of HbF synthesis and increase of total Hb content in β-thalassemic erythroblasts treated with KL with or without Dex

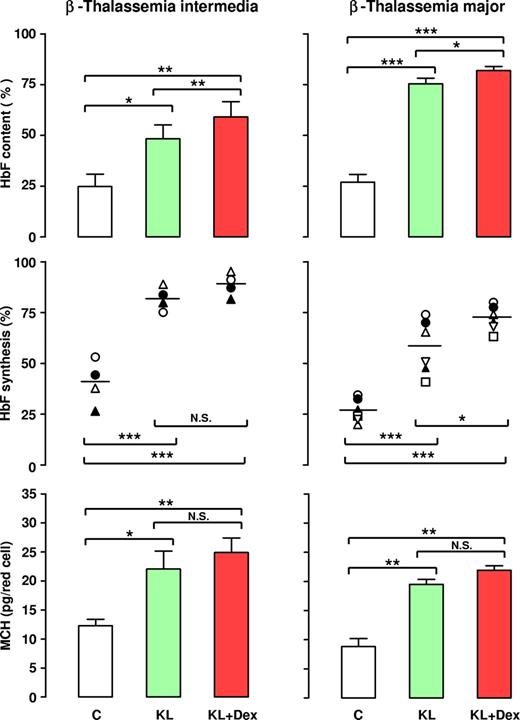

The reactivation of HbF synthesis in β-thalassemia was evaluated in a large number of patients by analysis of γ-globin chain content and synthesis, as evaluated by HPLC. In terms of γ-globin content, 10 separate experiments performed on β-TI HPCs showed that addition of KL alone or with Dex to erythroid cultures induced a strong increase in γ-globin chains (up to 48% or 60%, respectively, mean values), with respect to the KL-untreated group (24%; Figure 6 left top panel). Importantly, the HbF content was more elevated in KL plus Dex than in KL-supplemented cultures, in both the β-TI (P < .01) and β-TM (P < .05) groups. As predicted, the increase in HbF content in these patients was due to an enhanced rate of γ-globin synthesis: this was confirmed by 4 separate experiments on globin chain biosynthesis, assayed on cellular lysates of late erythroid cells incubated with [3H]-leucine. Particularly, the mean value of γ-chain synthesis (evaluated as the γ/[β + γ] ratio) was 90% and 82% in erythroid cells grown with KL plus Dex or KL alone, respectively, compared with 40% in KL-untreated culture (Figure 6 left middle panel; representative results in Figure 7). Notably, in these patients the increased level of HbF content caused a clear increase in the MCH level from 12.3 (± 0.9) pg/mature erythroid cell in control cultures to 22.05 (± 2.1) and 24.6 (± 1.6) in KL and KL plus Dex-supplemented groups, respectively (Figure 6 left bottom panel; mean values ± SEM of 6 experiments).

Effect of KL with and without Dex on HbF content, HbF synthesis, and MCH in β-TI and β-TM. β-TI (left panels) and β-TM (right panels) HPCs were grown in unilineage erythroid minibulk cultures in absence (C) or presence of KL (100 ng/mL), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). Mature erythroblasts were analyzed for their HbF content (top panels), HbF synthetic potential (middle panels), and total Hb content (MCH, bottom panels). With respect to HbF content, mean (± SEM) values from 10 (10 donors) and 7 (7 donors) separate experiments on β-TI and β-TM, respectively, are presented. For HbF synthesis, single experiments (4 and 7 for β-TI and β-TM, respectively) and means (horizontal bar) are shown. Bottom: mean values (± SEM) of MCH levels from 6 separate experiments on β-TI and β-TM, respectively are presented. Variance analysis was expressed as Bonferroni P values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

Effect of KL with and without Dex on HbF content, HbF synthesis, and MCH in β-TI and β-TM. β-TI (left panels) and β-TM (right panels) HPCs were grown in unilineage erythroid minibulk cultures in absence (C) or presence of KL (100 ng/mL), alone or in combination with Dex (10−8 M). Mature erythroblasts were analyzed for their HbF content (top panels), HbF synthetic potential (middle panels), and total Hb content (MCH, bottom panels). With respect to HbF content, mean (± SEM) values from 10 (10 donors) and 7 (7 donors) separate experiments on β-TI and β-TM, respectively, are presented. For HbF synthesis, single experiments (4 and 7 for β-TI and β-TM, respectively) and means (horizontal bar) are shown. Bottom: mean values (± SEM) of MCH levels from 6 separate experiments on β-TI and β-TM, respectively are presented. Variance analysis was expressed as Bonferroni P values. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

γ-globin chain synthesis. Representative HPLC scans of globin chain synthesis observed in mature erythroblasts derived from β-TI and β-TM HPC erythroid cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng) plus or minus Dex (10−8 M) and incubated overnight with [3H]-leucine.

γ-globin chain synthesis. Representative HPLC scans of globin chain synthesis observed in mature erythroblasts derived from β-TI and β-TM HPC erythroid cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng) plus or minus Dex (10−8 M) and incubated overnight with [3H]-leucine.

This striking effect of KL with and without Dex on HbF induction was confirmed in β-TM. In these patients, addition of KL to erythroid cultures reactivated HbF content from 27% to 75%, while a further increase up to 82% was induced by simultaneous addition of KL and Dex (Figure 6 right top panel; mean values of 7 experiments). In terms of HbF synthesis, evaluated as γ-α ratio, the experiments performed on 6 separate β-TM subjects demonstrated a γ-globin chain reactivation by KL alone or KL plus Dex up to 58% or 72%, respectively, with respect to 27% in the control group (Figure 6 right middle panel; representative results in Figure 7).

Here again, the increased level of HbF content induced a clear increase of MCH from 8.8 (± 0.66) pg/mature erythroid cell in control cultures to 18.48 (± 0.84) and 22.9 (± 0.75) in KL and KL plus Dex-supplemented groups, respectively (Figure 6 right bottom panel; mean values of 6 experiments).

Discussion

In β-thalassemic patients, the defective β-globin can be effectively replaced by normal γ-globin; in fact, these patients become anemic only after silencing of the γ-globin genes in the perinatal and postnatal periods. Furthermore, the ineffective erythropoiesis of β-thalassemia may hypothetically be alleviated by treatment with antiapoptotic agents.

The binding of KL to kit receptor on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells is essential for the development and expansion of the erythroid compartment: in genetic murine models, absence of KL (Steel mutation) or kit (White spotting mutation) results in prenatal or perinatal death due to severe macrocytic anemia.23 In human adult erythroid culture, KL treatment reactivates HbF synthesis and markedly potentiates cell proliferation.9,–11,13 Moreover, KL exerts a pronounced antiapoptotic effect on cultured erythroblasts15,17,18 ; on this basis KL has been considered as a potential therapeutic agent for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced anemia.18 Due to its effect on HbF reactivation and its proerythropoietic/antiapoptotic activity on erythroid precursors, KL may represent an ideal candidate to counteract the anemia and the accelerated death of erythroid precursors in β-thalassemia.

The main aim of this study was to provide a proof-of-principle for the therapeutic use of KL in thalassemic patients. Particularly, we investigated the in vitro effects of KL on HbF reactivation and expansion of β-TI and β-TM erythroid precursors. Specifically, we have used the model of unilineage erythroid culture generated by purified CD34+ HPCs in serum-free medium. This in vitro model closely reproduces the in vivo erythropoiesis pattern in terms of cell proliferation and differentiation/maturation, while allowing us to sample the cultures at different times in order to analyze sequential, discrete stages of the erythropoietic pathway in a more than 95% pure erythroid population.9,24

A series of experiments was focused on the characterization of the proliferative and antiapoptotic effects of KL plus Dex in unilineage erythroid suspension cultures. When the cells were grown in the absence of KL, the proliferation and differentiation/maturation of thalassemic erythroblasts was dramatically impaired, compared with normal control culture. However, KL addition was able to rescue the growth and differentiation/maturation of thalassemic erythroid cells almost up to the normal pattern through inhibition of apoptosis and dyserythropoiesis, particularly when KL was combined with a low concentration of Dex. Moreover, terminal erythroid maturation in KL plus Dex culture was delayed by 2 weeks, compared with control cultures not treated with these agents; it is therefore apparent that these 2 factors act, at least in part, by expanding the high proliferation window in early erythroid differentiation.

The molecular pathways activated by KL in normal erythroblasts to mediate its proliferative and antiapoptotic effects have been extensively investigated. Diverse genes and pathways activated by the kit receptor have been described, including the ERK-1/ERK-2 and AKT signaling pathways, the Pim-1 kinase, the transcription factors Tal-1 and Id-2, and the antiapoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL.13,15,18,25 Other genes, such as Notch and HMG (high mobility group) family members, may be involved in the erythroid expansion induced by KL.26 Further studies are necessary to clarify the interplay of these factors in KL-induced erythroid cell proliferation and survival.

Considerable progress has been achieved in the pharmacologic induction of HbF synthesis in β-hemoglobinopathies,27 the successful reactivation of HbF synthesis in animal models led to clinical trials in β-thalassemia with cytotoxic drugs (eg, 5-azacytidine, hydroxyurea),28,,–31 butyrate compounds,28,32 and Epo.30,33 However, these studies were abandoned due to toxicity and modest HbF reactivation, inadequate to influence the clinical course in most patients.34 Moreover, the complexity of globin gene expression regulation suggests that combination therapies exploiting different mechanisms of HbF reactivation may be needed to produce high levels of HbF in thalassemic patients.

In this study, the addition of KL plus Dex to β-thalassemic HPC cultures induced a sharp increase in erythroblast HbF content, up to levels 3-fold higher than in healthy controls and comparable with fetal values. Interestingly, this effect was observed in all patients, independent of their genotype, even in late stage of erythroid differentiation-maturation. This increase was seemingly not caused by defective erythroblast maturation, in that HbF content was consistently monitored in cultures containing 80% to 90% of mature erythroblasts. Furthermore, recruitment of erythroid burst-forming units (BFU-Es) with elevated HbF synthetic potential was ruled out by unicellular culture experiments (results not shown), as previously reported in normal erythroid cultures.13

Altogether, our studies indicate that in β-thalassemic cultures KL, alone or combined with Dex, stimulates erythroid cell proliferation and differentiation/maturation, almost up to the pattern observed in normal control cultures; these effects are mediated by reactivation of HbF synthesis, combined with the intrinsic antiapoptotic effect of KL.

In view of possible future clinical applications, it is noteworthy that the peak effect of KL on erythroid cell proliferation and HbF reactivation was almost completely reached at the concentration of 10 ng/mL. Furthermore, Dex acted at a dosage used in immunologic disease therapy (10−8 M).35

These in vitro studies should be extended to animal models, such as β-thalassemic mice, to evaluate the optimal in vivo doses of KL plus Dex, particularly in view of possible side effects. Preclinical studies in primates and mice suggested that KL occasionally causes significant allergic side effects, related to induction of mastocytosis.36,37 This was confirmed by subsequent clinical trials in HIV and cancer patients,38,39 aplastic anemia,40 cord blood transplantation,41 and postablative chemotherapy42 ; specifically, mild allergic reactions (eg, pruritus, urticaria, cutaneous angioedema) were reported in a minority of patients, while severe ones (eg, laringospasm) were observed only in exceptional cases. In the most extensive phase 3 trial, KL was used for stimulation of stem-cell mobilization; 100 patients received KL (Stemgen) at 20 μg/Kg per day for 5 consecutive days and 3 of them reported systemic allergic reactions, resolved after treatment with steroids.43 The potential use of KL for treatment of β-thalassemic patients implies a chronic administration protocol, possibly based on sequential therapy cycles: this protocol may amplify the potential risk of allergic reactions, and should be considered cautiously in view of these possible side effects.

In conclusion, our studies provide a significant experimental basis for the development of preclinical models of KL-based therapy in β-thalassemia, aiming to possibly decrease or eliminate the need for transfusions and improve the quality of life with this disease.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Agostino for technical support, M. Fontana for editorial assistance, and A. Zito for graphics.

Authorship

Contribution: M.G. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; O.M. and A.M. performed research and analyzed data; L.P. performed research; P.C. contributed new reagents and analytical tools and analyzed clinical data; U.T. performed research and wrote the paper; C.P. planned the research strategy and wrote the paper.

M.G. and O.M. contributed equally to this paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cesare Peschle or Marco Gabbianelli, Department of Hematology, Oncology, and Molecular Medicine, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena, 299-00161 Rome, Italy; e-mail: cesare.peschle@iss.it or marco.gabbianelli@iss.it.

![Figure 1. KL dose-response in β thalassemic patients. Cell growth (top panels) and HbF content (bottom panels) in minibulk HPC unilineage erythroid cultures derived from a representative β-TI (left panels) and β-TM patient (right panels), supplemented or not with graded amounts of KL (1, 10, or 100 ng/mL). The total cell number is shown in top panels. The percentage of HbF content (evaluated as the γ/[β + γ] and γ/α ratio in β-TI and β-TM, respectively) is reported in bottom panels.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/1/10.1182_blood-2007-06-097550/3/m_zh80040812900001.jpeg?Expires=1769148936&Signature=rC-EFHG3P-8l~92iqZ9wJOKyRFiNgSBwKXttQmz~ApUOH0fEwWnJ1-~yVCeVDzyT0QGBwYrrOf8Sl8tKhhrl9PfZo8BBSgsIS74UBsA8PgJr6mOOTvpcFzMvSNHJ5h6GNhkC1xGkXS49twMq05aQXT3T8fG6LenXvbcH02BF4iy3ntXmmlXfzidD1LUEEsIXRo557LpNyDM~8dnCWEDjMmqRL09ugSVSPtC4zPRWTSG0deTSePpgSZ1vozC~KwuJXf09Wsei-S09OyjxQuHT9uWTiyTousRrma0n3yH-paVQ6jgvzEU1PucfQZOUd8f~-TJXGZIV854NZ5OttdbxEA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![Figure 7. γ-globin chain synthesis. Representative HPLC scans of globin chain synthesis observed in mature erythroblasts derived from β-TI and β-TM HPC erythroid cultures supplemented or not with KL (100 ng) plus or minus Dex (10−8 M) and incubated overnight with [3H]-leucine.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/111/1/10.1182_blood-2007-06-097550/3/m_zh80040812900007.jpeg?Expires=1769148937&Signature=aTtHAb-gYUombgc13PVutpyqbW0NGB8p0F4c9tVWBEd4ZPRntxBpzkJ2iFZeVwJHuMKnm1qoybotCEYVCvwimnqXTCIsSSx2oSp~nWIk36c1uftx6XngoZYc7YFqv-uplvvmM3eddbAWCj4mlSGTZ1deXlThy-MGUcwmbca3bJjUSkjjSSc2YT8qe1K6K55~rITPxVUaiM1wBgUoJtgGOe9J6IAb5YBd80w4obN507N16u2k4Vw-zffNGta6X3EkAx7xHI20MKgnwzcembAe7Cy24BFIIAiFwRdK7L7EHkFPI4805e1k6UvkbhZzpUuvYZSxDmxc~kIS-36-3fKCbg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal