Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Migration of donor-derived T cells into GVHD target organs plays an essential role in the development of GVHD. β2 integrins are critically important for leukocyte extravasation through vascular endothelia and for T-cell activation. We asked whether CD18-deficient T cells would induce less GVHD while sparing the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effect. In murine allogeneic bone marrow transplantation models, we found that recipients of CD18−/− donor T cells had significantly less GVHD morbidity and mortality compared with recipients of wild-type (WT) donor T cells. Analysis of alloreactivity showed that CD18−/− and WT T cells had comparable activation, expansion, and cytokine production in vivo. Reduced GVHD was associated with a significant decrease in donor T-cell infiltration of recipient intestine and with an overall decrease in pathologic scores in intestine and liver. Finally, we found that the in vivo GVL effect of CD18−/− donor T cells was largely preserved, because mortality of the recipients who received transplants of CD18−/− T cells plus tumor cells was greatly delayed or prevented. Our data suggest that strategies to target β2 integrin have clinical potential to alleviate or prevent GVHD while sparing GVL activity.

Introduction

The integrins are a family of heterodimeric transmembrane proteins functioning in cell-cell and cell–extracellular matrix adhesion. There are currently 18 known subunits and 8 subunits in mammals, and the integrins relevant to the immune system include those in the β1, β2, and β7 families.1 The β2 family is restricted to leukocytes, and includes CD11a/CD18 (LFA-1), CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1), CD11c/CD18, and CD11d/CD18. The CD11a/CD18 integrin is expressed constitutively on all leukocytes, whereas the other members of this family are restricted to various subsets. The β2 integrins bind ligands in the immunoglobulin superfamily, which are expressed by leukocytes and endothelial and epithelial cells, called intracellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, -2, and -3).2 Integrins function in both tethering and rolling of leukocytes on endothelium through low-affinity and avidity interactions, and in the firm arrest and transmigration of leukocytes through the vascular wall. In addition to their role in leukocyte migration, integrins function in T-cell activation by stabilizing the interaction of T cells with antigen-presenting cells (APCs). The interaction of CD11a/CD18 integrin on T cells with ICAM-1 expressed on APCs is a critical component of the immunologic synapse.3 Furthermore, integrins can provide costimulatory signals to T cells during activation, facilitating proliferation and acquisition of effector functions.4

Absence of CD18 leads to leukocyte adhesion deficiency type 1 (LAD1).5,6 The severity of this disease correlates with the degree of loss of CD18.7 In the absence of CD18, severe defects in cell-cell cooperation occur, leading to a lack of homotypic lymphocyte adhesion and impaired T-cell activation accompanied by a reduced IL-2 release.4,8,9 In a murine model for LAD1 with a CD18 null mutation (CD18null), it has been shown that lack of the β2 integrin subunit markedly impairs T-cell extravasation.10

Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is an effective therapeutic option with a curative potential for many malignant diseases.11 The therapeutic potential of allogeneic BMT relies on the graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effect to eradicate residual tumor cells by immunologic mechanisms. Under this therapeutic procedure, graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) remains the major complication, as it leads to high morbidity and mortality of the patient. GVHD is initiated by mature donor T cells that recognize disparate histocompatibility antigens of the recipient and cause injuries in skin, liver, gastrointestinal (GI) epithelium, and elsewhere.12 Despite the widely appreciated magnitude of this complication and the extensive efforts to overcome the problem, no strategy has been established to selectively induce tolerance of alloreactive T cells and thus effectively control GVHD while sparing the GVT effect.

Recent studies have demonstrated that activated effector T cells exit lymphoid tissues and traffic to parenchymal target organs such as GI tract, liver, skin, and lung, where they cause tissue damage during development of GVHD. T-cell trafficking through the circulation, secondary lymphoid organs, and specific tissues is a multifaceted process requiring precise communication among lymphocytes, endothelial cells, and the extracellular matrix; chemokines, selectins, integrins, and their receptors play crucial roles in these complex interactions. The expression of specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors on T cells, in combination with a spatial and temporal expression pattern of the ligands for these receptors, is largely responsible for the tissue tropism of T-cell migration.13

Given that CD18 plays a critical role in T-cell activation, function, and trafficking, we hypothesized that CD18 expression on donor T cells may be involved in the development of GVHD and graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) activity. In the current study, we have analyzed the ability of wild-type (WT) and CD18-deficient donor T cells to expand, produce cytokines, infiltrate into host issues, cause systemic GVHD, and exert GVL activity.

Methods

Mice

Normal B6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). Mice with a CD18 null mutation (CD18−/−) were generated as previously described, and were bred by crossing into C57BL/6J (B6) background.10,14 The strain with CD18 mutation was bred and all the mice used in this study were housed in H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute (Tampa, FL). Experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of T cells and bone marrow cells from donor mice

T cells were purified from pooled spleen and lymph node cells by positive selection through Thy1.2 with a magnetic cell separation system (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA) as described previously.15,16 CD25− T cells were purified by negative selection to remove non–T cells and CD25+ cells. Non–T cells, including B cells, natural killer (NK) cells, dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages, granulocytes, and erythroid cells, were indirectly magnetically labeled by using a cocktail of biotin-conjugated Abs against CD45R (B220), CD49b (DX5), CD11b (Mac-1), and Ter-119, as well as antibiotin MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). Isolation of T cells was achieved by depletion of the magnetically labeled cells. Naive T cells were then further isolated by positive selection through CD62L. Bone marrow (BM) was harvested from tibia and femurs, and T cells were depleted through complement lysis of Thy1.2+ cells.

Transplantation

In myeloablative BMT models, BALB/c mice at 8 to 10 weeks old were exposed to 800 to 900 cGy of total body irradiation from 137Cs source at 120 cGy/minute. Sulfamethoxazole trimethoprim (Hi-Tech Pharmacal Inc, Amityvile, NY) was added to the drinking water of those irradiated mice starting at the day before irradiation and through out the entire experiments. T-cell–depleted (TCD) BM cells alone or in combination with purified T cells from indicated donors were injected via the tail vein to recipients within 24 hours after irradiation. Recipient mice were monitored every other day for clinical signs of GVHD, such as ruffled fur, hunched back, inactivity or diarrhea, and mortality. Animals judged to be moribund were killed and counted as GVHD lethality.

Bioluminescent imaging for tumor growth

The A20, a B lymphoma cell line derived from BALB/c mice (ATCC, Rockville, MD), was retrovirally transduced with a luc/neo plasmid using a protocol described previously.17 Transduced cells were cultured in 400 μg/mL G418 (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD), outgrowing cells were subcloned, and a high-expressing clone (A20-luc/neo) was further expanded and cryopreserved. Animals that received A20-luc/neo were given intraperitoneal (150 mg/kg) D-Luciferin (Xenogen, Alameda, CA). At 10 minutes after injection, mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and placed supine in the Xenogen IVIS bioluminescence imaging system, and recordings were made for 2 to 5 minutes. Pseudocolor images showing whole-body distribution of bioluminescent signal were superimposed on conventional grayscale photographs.

CFSE labeling and flow cytometric analysis

For measurement of proliferative response in vivo, T cells were labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and transferred into irradiated allogeneic recipients, and we analyzed the CFSE dilution of T cells with flow cytometry as described previously.16 Flow cytometry (2-, 3- or 4-color) was performed to measure the expression of surface molecules according to standard techniques. Analysis was performed by using a FACScan or FACSCalibur and CellQuest (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) or FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). All the fluorescence-conjugated mAbs were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA).

Histopathologic analysis

Histopathology on small and large bowel, liver, and skin was assessed by an expert pathologist (C.L.) in a blinded fashion. Formalin-fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin. The tissue sections were examined under microscope, and the severity of the tissue damage was graded with a semiquantitative scoring system. Intestinal and liver tissues were scored for 19 to 22 different parameters associated with GVHD.18 The degree of skin GVHD was graded as 0 to 4 as previously described.19

Lymphocyte isolation from liver and gut

We adapted the protocol established by others to isolate lymphocytes from liver and gut.20 Briefly, small intestine was dissected from the gastric-duodenal junction to the ileocecal junction. Intestines were flushed with 2% fetal bovine serum/phosphate-buffered saline (FBS/PBS), cut into 1-cm–long pieces, and incubated in complete medium containing 0.5 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 1 hour at 37°C with continuous shaking. Intestinal pieces were then vortexed for 15 seconds, and the supernatant was strained and centrifuged at 325g for 5 minutes. Pellets were resuspended in 40% Percoll (Sigma, St Louis, MO), overlaid on 70% Percoll, and centrifuged at 1300g for 30 minutes. Lymphocytes were recovered from the interface. Livers were homogenized and passed through a 70-μm cell strainer. Pellets were resuspended in PBS with 2% FBS/PBS, overlaid on Ficoll, and centrifuged at 1300g for 20 minutes. Lymphocytes were recovered from the interface.

Cytokine analysis

Blood samples were obtained from BM transplant recipients at the time specified, and cytokine analysis was performed as described previously.21 Briefly, IFNγ, TNFα, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-5 were measured in recipient serum using a cytomertic bead array kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences).

CTL assay

Cytotoxic activity was measured by using a 51Cr-release assay as previously described.15 Briefly, spleen cells from each recipient were used as effectors against 51Cr-labeled A20, EL-4, or Yac-1 targets with an effector-target (E/T) at various ratios. Chromium release was measured after 4 to 5 hours of incubation, and percentage of cytotoxicity was calculated as (experimental release − spontaneous release) / (maximal release − spontaneous release) × 100%.

Statistical analysis

The log-rank test was used to detect statistical differences in recipient survival in GVHD experiments. The Student t test was used to compare percentages or numbers of donor T cells.

Results

CD18−/− T cells have markedly reduced ability to induce acute GVHD

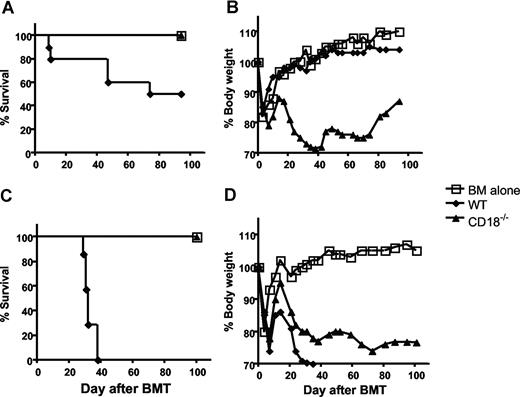

Previous studies have indicated that CD18 plays critical roles in T-cell activation and migration;1 we asked whether CD18 is essential for donor T cells to induce acute GVHD. To this end, we purified total T cells from either WT or CD18-deficient B6 mice and transferred them together with TCD BM cells into lethally irradiated BABL/c recipients, in which donor T cells cause epithelial damages leading to GVHD lethality. As expected, recipients of WT T cells at 106/mouse showed typical clinical feature of GVHD, including hunched back, ruffled fur, hair loss, diarrhea, and body weight loss. In fact, 50% of these mice died within 75 days after BMT, and residual mice kept GVHD manifestations through out the experiment. In contrast, recipients of CD18−/− T cells at 106/mouse did not show clinical features of GVHD and resumed weight gain similar to the recipients of TCD BM alone (Figure 1A,B), suggesting that CD18 plays an essential role in the development of GVHD.

CD18 affects GVHD development. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells from B6 donors alone or with T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. (A) Survival of recipients given transplants of TCD BM cells alone (n = 4) or with 1 × 106 WT (n = 8) or CD18−/− (n = 8) total T cells. (B) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel A. (C) Survival of recipients given transplants of TCD BM cells alone (n = 4) or 2 × 106 WT (n = 7) or CD18−/− (n = 7) T cells after removal of CD25+ cells. (D) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel B. P values indicate the differences between recipients of WT versus CD18−/− cells.

CD18 affects GVHD development. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells from B6 donors alone or with T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. (A) Survival of recipients given transplants of TCD BM cells alone (n = 4) or with 1 × 106 WT (n = 8) or CD18−/− (n = 8) total T cells. (B) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel A. (C) Survival of recipients given transplants of TCD BM cells alone (n = 4) or 2 × 106 WT (n = 7) or CD18−/− (n = 7) T cells after removal of CD25+ cells. (D) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel B. P values indicate the differences between recipients of WT versus CD18−/− cells.

It has been shown that absence of CD18 leads to diminished development and function of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory (Treg) cells22 (H. Wang et al, February 2007, unpublished observation), and Treg cells suppress GVHD development.23 To exclude the influence of Treg cells in this system, we removed CD25+ cells and compared the ability of CD25− WT or CD18−/− T cells to induce GVHD. Total WT T cells at 1 × 106/mouse induce GVHD lethality only in a proportion of recipients (Figure 1A), but lethality was consistently induced by 2 × 106/mouse; we therefore chose to use the later cell dose. At 2 × 106/mouse, WT T cells caused severe GVHD and led to death of 100% recipients within 40 days after transplantation. In contrast, CD18−/− T cells did not cause any death of the recipients, although they were not able to resume their body weights as recipients of TCD BM alone (Figure 1C,D). These results indicate that CD18−/− T cells have impaired activity to cause GVHD.

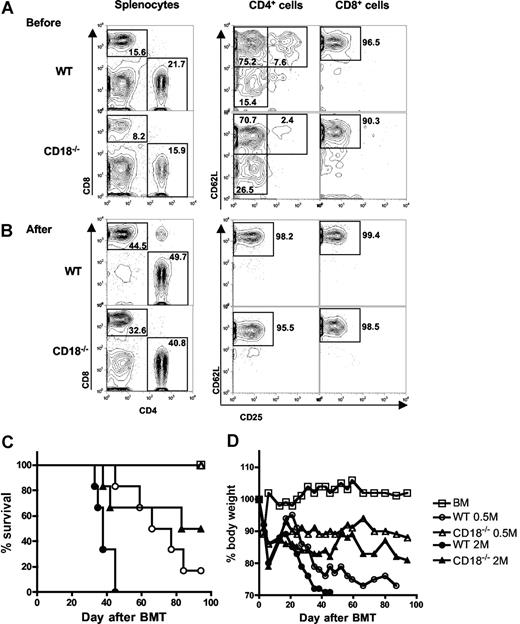

Previous work demonstrated that T cells with memory phenotype (ie, CD44high and CD62Llow) accumulated in CD18−/− mice as compared with WT mice,10 and other studies showed that memory T cells are incapable of inducing GVHD.24 Thus, it is possible that diminished ability of CD18−/− T cells in GVHD development was due to increased proportion of memory T cells. To test this possibility, we further purified CD25−/CD62Lhigh naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− donors. Before purification, CD18−/− CD4+ T cells contained fewer CD25+ Treg cells and more CD62Llow memory cells compared with WT CD4+ T cells, and CD18−/− CD8+ T cells also contained more CD62Llow memory cells compared with WT CD8+ T cells (Figure 2A). After purification, T cells were more than 95% CD25−CD62Lhigh naive cells, which were used for further experiments hereafter. To evaluate their potential in quantity for inducing GVHD, we compared the ability of WT and CD18−/− naive T cells to cause GVHD at 2 cell doses. At 2 × 106/mouse, WT T cells led to 100% GVHD lethality within 40 days after transplantation, whereas CD18−/− T cells caused 35% lethality with significantly delayed death. At 0.5 × 106/mouse, WT T cells induced 80% lethality, whereas CD18−/− T cells caused no lethality (Figure 2C). Moreover, GVHD in the recipients that were given transplants of high-dose CD18−/− T cells was still milder than that in the recipient with low-dose WT T cells, reflected by percentage of recipient survival and body weight loss (Figure 2C,D). Collectively, these data clearly demonstrate that naive WT T cells are significantly more pathogenic than naive CD18−/− T cells in the induction of GVHD.

Naive T cells from CD18−/− donors have diminished ability to induce GVHD. Spleen and lymph nodes were harvested from WT or CD18−/− donors, and CD25−CD62L+ naive T cells were purified with magnetic beads as described in “Methods.” CD25 and CD62L expression were shown on WT or CD18−/− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells before (A) and after (B) purification. Numbers in the panels indicate the percentages of cells in the gate as shown among total splenocytes (left panels), CD4+ cells (middle panels), or CD8+ cells (right panels). Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD-BM cells alone or with naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. (C) Survival of recipients given TCD BM cells alone (n = 12) or with WT or CD18−/− naive T cells at 0.5 × 106 (0.5 M) or 2 × 106 (2 M) per mouse. The recipients with donor T cells at 2 M were 12 mice per group, and there were 6 mice per group at 0.5 M. (D) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel C.

Naive T cells from CD18−/− donors have diminished ability to induce GVHD. Spleen and lymph nodes were harvested from WT or CD18−/− donors, and CD25−CD62L+ naive T cells were purified with magnetic beads as described in “Methods.” CD25 and CD62L expression were shown on WT or CD18−/− CD4+ and CD8+ T cells before (A) and after (B) purification. Numbers in the panels indicate the percentages of cells in the gate as shown among total splenocytes (left panels), CD4+ cells (middle panels), or CD8+ cells (right panels). Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD-BM cells alone or with naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. (C) Survival of recipients given TCD BM cells alone (n = 12) or with WT or CD18−/− naive T cells at 0.5 × 106 (0.5 M) or 2 × 106 (2 M) per mouse. The recipients with donor T cells at 2 M were 12 mice per group, and there were 6 mice per group at 0.5 M. (D) Mean changes in percentage of body weights for the recipients as in panel C.

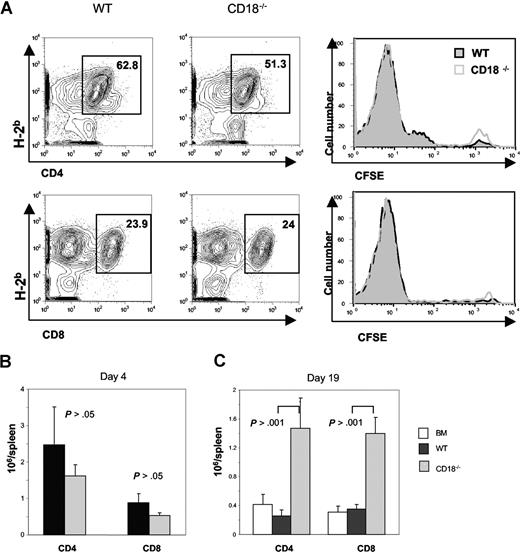

WT and CD18−/− T cells have comparable activation and expansion in response to alloantigen

The impaired ability of alloreactive CD18−/− T cells could be attributed to an intrinsic defect in T-cell activation and/or expansion. To measure the ability of CD18−/− T cells to undergo proliferation in response to alloantigens in vivo, CFSE-labeled T cells were transferred into lethally irradiated BALB/c recipients, and proliferation kinetics were compared with those of CFSE-labeled WT T cells. We found that both types of T cells divided equally well (Figure 3A), and expanded in a similar level for both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the recipient 4 days after cell transfer (Figure 3B). In a separate experiment, BALB/c recipients were given transplants of TCD BM from B6 congeneic Ly5.1 donors alone, or plus naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− mice. At 3 weeks after BMT, we measured the presence of donor T cells (H2b+Ly5.1−) in recipient spleen and blood. We found that significantly more donor CD4+ and CD8+ T cells accumulated in the spleen of recipients that were given transplants of CD18−/− T cells than that WT T cells (Figure 3C). Significantly more CD18−/− T cells, especially CD4+ cells, also accumulated in peripheral blood than did WT T cells (Table 1). These data indicate that CD18−/− T cells did not have an impaired expansion in vivo.

CD18−/− T cells have intact activation and expansion in response to alloantigen in vivo. WT or CD18−/− T cells (CD25−CD62L+) were labeled with CFSE and then injected intravenously into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice at 5 × 106 cells/mouse. Cell division and expansion were determined 4 days after cell transfer. (A) Mean of percentage donor (H2b+) CD4 (top panels) and CD8 T cells (bottom panels) are shown in spleens of recipients given WT (left panels) or CD18−/− (middle panels) T cells. CFSE profiles are shown on gated CD4 and CD8 cells (right panels) from WT (black lines) or CD18−/− (gray lines) donors. (B) Mean of absolute numbers of CD4 or CD8 cells per spleen in recipients that were given WT (■) or CD18−/− (▩) donor T cells as shown in panel A. Brackets show SEM from 3 mice each group, and data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (C) WT or CD18−/− T cells (CD25−CD62L+) were injected intravenously into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice at 2 × 106 cells/mouse, and cell expansion was determined 19 days after cell transfer. Mean of absolute numbers of CD4 or CD8 cells per spleen was shown in recipients given WT (■) or CD18−/− (▩) donor T cells. Brackets indicate standard errors of the mean from 3 to 4 mice each group, and data represent 1 of 4 replicate experiments.

CD18−/− T cells have intact activation and expansion in response to alloantigen in vivo. WT or CD18−/− T cells (CD25−CD62L+) were labeled with CFSE and then injected intravenously into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice at 5 × 106 cells/mouse. Cell division and expansion were determined 4 days after cell transfer. (A) Mean of percentage donor (H2b+) CD4 (top panels) and CD8 T cells (bottom panels) are shown in spleens of recipients given WT (left panels) or CD18−/− (middle panels) T cells. CFSE profiles are shown on gated CD4 and CD8 cells (right panels) from WT (black lines) or CD18−/− (gray lines) donors. (B) Mean of absolute numbers of CD4 or CD8 cells per spleen in recipients that were given WT (■) or CD18−/− (▩) donor T cells as shown in panel A. Brackets show SEM from 3 mice each group, and data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (C) WT or CD18−/− T cells (CD25−CD62L+) were injected intravenously into lethally irradiated BALB/c mice at 2 × 106 cells/mouse, and cell expansion was determined 19 days after cell transfer. Mean of absolute numbers of CD4 or CD8 cells per spleen was shown in recipients given WT (■) or CD18−/− (▩) donor T cells. Brackets indicate standard errors of the mean from 3 to 4 mice each group, and data represent 1 of 4 replicate experiments.

Absolute cell numbers in peripheral blood (×104/mL)

| Group . | WBC . | Ly5.1-H-2b+ . | CD4+ . | CD8+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 145 ± 68 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| WT | 156 ± 83 | 11.7 ± 6.9 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 4.8 ± 2.9 |

| CD18−/− | 231 ± 45 | 61.1 ± 35.7* | 48.7 ± 29.8* | 5.6 ± 3.1 |

| Group . | WBC . | Ly5.1-H-2b+ . | CD4+ . | CD8+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 145 ± 68 | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

| WT | 156 ± 83 | 11.7 ± 6.9 | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 4.8 ± 2.9 |

| CD18−/− | 231 ± 45 | 61.1 ± 35.7* | 48.7 ± 29.8* | 5.6 ± 3.1 |

n.d. indicates undetectable.

WT vs CD18−/−, P < .05.

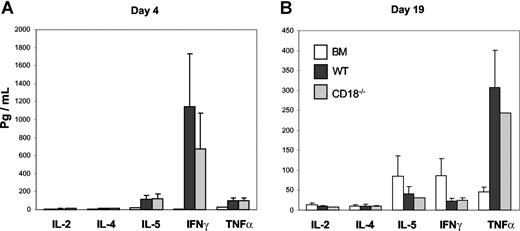

One feature of activated T cells is to produce various cytokines, which contribute to the development of GVHD. To ask whether the diminished ability of CD18−/− T cells was due to the defect in the production of inflammatory cytokines, we measured the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFNγ, and TNFα in recipient serum on days 4 and 19 after transplantation and found no significant difference for any cytokine at either time point measured in the recipients of WT or CD18−/− donor T cells (Figure 4A,B). These data indicate that CD18−/− T cells have intact activation and differentiation.

CD18−/− T cells produce comparable levels of cytokines as WT cells in allogeneic recipients. Indicated cytokines were measured in recipient serum on day 4 (A) or day 19 (B) after BMT as described in “Methods.” The data are presented as means ± SD of 5 to 6 mice per group, and represent 1 of 3 replicate experiments.

CD18−/− T cells produce comparable levels of cytokines as WT cells in allogeneic recipients. Indicated cytokines were measured in recipient serum on day 4 (A) or day 19 (B) after BMT as described in “Methods.” The data are presented as means ± SD of 5 to 6 mice per group, and represent 1 of 3 replicate experiments.

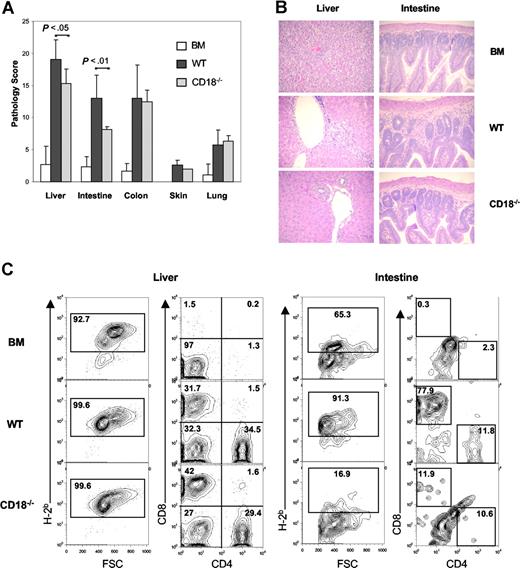

CD18−/− T cells cause less hepatic and intestinal damages

To investigate whether recipients of CD18−/− T cells had less severe target organ GVHD damage, we analyzed GVHD-associated organ damage in liver, terminal ileum, colon, skin, and lung. A semiquantitative histopathologic analysis was performed in a blinded fashion on tissue samples from these target organs. We found that CD18−/− T cells caused significantly less GVHD in recipient liver (P = .03) and small intestine (P = .008) than did WT T cells at day 19 after transplantation. No significant difference in colon, skin, or lung damage was found between recipients of WT and those of CD18−/− T cells (Figure 5A).

Recipients of CD18−/− donor T cells have significant less pathologic damage in intestine and liver. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells alone or with naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. On day 19, GVHD target organs, including liver, small intestine, colon, skin, and lung, were harvested for evaluation of histopathology as described in “Methods.” (A) Combined results of pathology scores for 5 to 6 mice in each group. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean in the group. (B) Representative micrographs from recipient livers and intestines of BM alone, WT, and CD18−/− groups with original magnification ×600. Images were captured with an Olympus BX 40 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a 10×/0.40 numerical aperture objective lens. Image acquisition was performed with a JVC GC-Qx 5HDU digital camera (JVC, Wayne, NJ). (C) Donor T-cell infiltration was determined by flow cytometry in liver and intestine. Left panels show the percentage of H2b+ in total mononuclear cells isolated, and right panels show the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in gated H2b+ cells. The data show average percentage of each cell population among 3 to 4 mice per group, and represent 1 of 3 replicate experiments.

Recipients of CD18−/− donor T cells have significant less pathologic damage in intestine and liver. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice were given intravenous injections of 5 × 106 TCD BM cells alone or with naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. On day 19, GVHD target organs, including liver, small intestine, colon, skin, and lung, were harvested for evaluation of histopathology as described in “Methods.” (A) Combined results of pathology scores for 5 to 6 mice in each group. Error bars indicate the standard errors of the mean in the group. (B) Representative micrographs from recipient livers and intestines of BM alone, WT, and CD18−/− groups with original magnification ×600. Images were captured with an Olympus BX 40 microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) equipped with a 10×/0.40 numerical aperture objective lens. Image acquisition was performed with a JVC GC-Qx 5HDU digital camera (JVC, Wayne, NJ). (C) Donor T-cell infiltration was determined by flow cytometry in liver and intestine. Left panels show the percentage of H2b+ in total mononuclear cells isolated, and right panels show the percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in gated H2b+ cells. The data show average percentage of each cell population among 3 to 4 mice per group, and represent 1 of 3 replicate experiments.

On close histopathologic analysis of small intestine, we observed that recipients of WT T cells had moderate to severe villus blunting, crypt degeneration, lamina propria inflammation, atrophy, epithelial apoptosis, and mononuclear cell infiltration. These pathologic changes were minimal to moderate in recipients of CD18−/− T cells and minimal or absent in recipients of TCD BM cells alone (Figure 5B). We also observed moderate mononuclear cell infiltration and hepatocellular damage in the liver of recipients of WT T cells, but mild infiltration and minimal damage in the liver of recipients of CD18−/− T cells (Figure 5B).

To test whether intestine and liver GVHD was directly associated with donor T-cell infiltration into these target organs, we determined the percentages of WT versus CD18−/− donor T cells in recipient liver and intestine on 20 days after transplantation. As negative controls without GVHD, recipients of TCD BM alone did not have donor T cells in either intestine or liver (Figure 5C). The intestinal mucosa contained significantly higher percentages of donor T cells in recipients of WT cells than in recipients of CD18−/− cells (Figure 5C right panels). In the latter, we typically had a low cell yield from recipient intestine (ie, less than 106/mouse), and the total number of cells varied from individuals (data not shown). In the liver, the percentages of donor T cells were similar in recipients of WT or CD18−/− cells (Figure 5C left panels). However, we repeatedly observed that the total numbers of mononuclear cells were significantly higher in the recipients of CD18−/− T cells than in recipients of WT cells 3 weeks after BMT (Table 2). These data suggest that more CD18−/− than WT T cells accumulated in recipient liver at the late time point observed.

Absolute cell numbers in liver (×106/mL)

| Group . | Total . | H-2b+ . | H-2b+CD4+ . | H-2b+CD8+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.04 ± 0.05 |

| WT | 2.56 ± 0.36 | 2.42 ± 0.35 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.22 |

| CD18−/− | 4.93 ± 1.47* | 4.80 ± 1.38* | 1.61 ± 0.44† | 1.90 ± 0.70* |

| Group . | Total . | H-2b+ . | H-2b+CD4+ . | H-2b+CD8+ . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | 1.00 ± 0.12 | 0.83 ± 0.06 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.04 ± 0.05 |

| WT | 2.56 ± 0.36 | 2.42 ± 0.35 | 0.44 ± 0.09 | 0.78 ± 0.22 |

| CD18−/− | 4.93 ± 1.47* | 4.80 ± 1.38* | 1.61 ± 0.44† | 1.90 ± 0.70* |

WT vs CD18−/−, P < .05.

WT vs CD18−/−, P < .01.

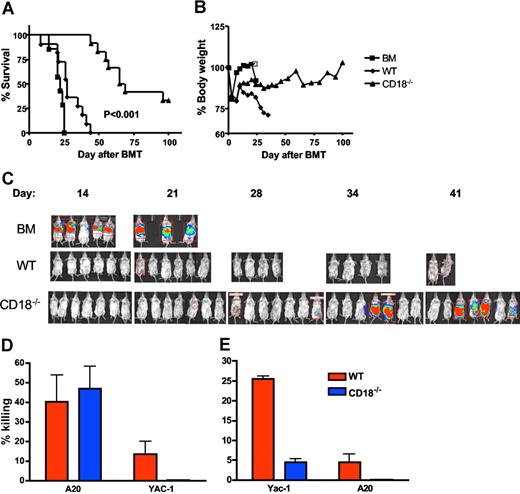

GVL activity is largely preserved for CD18−/− T cells

To assess the effects of β2 integrin deficiency on the GVT activity of alloreactive T cells, we performed experiments in the B6 BALB/c GVHD model with the A20 lymphoma cell line (Figure 6). As expected, recipients of TCD BM plus A20 cells had rapid death within 25 days after transplantation (Figure 6A) without body weight loss (Figure 6B). In vivo bioluminescence imaging detected very strong signals on days 14 and 20, reflecting rapid tumor growth in these recipients prior to death (Figure 6C). Recipients of TCD BM plus WT T cells with A20 cells died within 40 days after transplantation (Figure 6A) with substantial weight loss (Figure 6B), but little or no tumor growth was detected in these recipients throughout the observation period (Figure 6C), indicating that these recipients died from GVHD. Recipients of TCD BM plus CD18−/− T cells with A20 cells had a much-delayed death, and a proportion of these recipients had a long-term survival (Figure 6A). Some of these recipients had a considerable body weight loss but others did not, which was reflected in the unstable body weight curve for this group (Figure 6B). It was also the case that some of these recipients had a strong signal for tumor growth, but others did not (Figure 6C). Collectively, death of these recipients was either due to GVHD with weight loss but little or no tumor signal, or due to tumor growth with strong tumor signal but little or no weight loss. Significantly, a subset of CD18−/− T-cell recipients (approximately 35%) survived free from tumor and GVHD.

GVL activity is partially preserved in CD18−/− T cells. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice underwent BMT with 5 × 106 TCD BM cells alone or plus 2 × 106 naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. Recipients were given 2 × 103 A20 tumor cells with luciferase transgene as a separate intravenous injection at the same time of transplantation. Recipient survival (A) and body weight changes (B) are shown. Numbers of recipients given transplants of BM alone or plus WT or CD18−/− T cells were 7, 11, and 12, respectively, and data are pooled from 2 replicate experiments. (C) Recipients were tracked for in vivo luminescence 10 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of firefly luciferin; data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (D) BMT was set as in panels A and B, and BALB/c recipients of WT or CD18−/− T cells were killed 2 weeks after transplantation. Splenocytes of each recipient were assayed directly for cytotoxicity without in vitro restimulation. The activity of cytolytic effectors was measured in a 4- to 5-hours cytotoxic assay against A20 or Yac-1 at an E/T ratio of 100:1. The data represent the means (± 1 SD) of percentage of specific killing from 3 to 4 replicate mice each group, and the percentage of killing is normalized based on the number of total T cells in the spleen. The assay was run in triplicate with less than 5% SE, and data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (E) Splenocytes from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors were stimulated with IL-2 for 3 days and used as effector cells to kill Yac-1 (NK-sensitive targets) or A20 cells an E/T ratio of 100:1. The data represent the means (± 1 SD) of percentage of specific killing from 2 replicate mice each group, and triplicate wells were set in vitro with less than 5% SE.

GVL activity is partially preserved in CD18−/− T cells. Lethally irradiated BALB/c mice underwent BMT with 5 × 106 TCD BM cells alone or plus 2 × 106 naive T cells from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors. Recipients were given 2 × 103 A20 tumor cells with luciferase transgene as a separate intravenous injection at the same time of transplantation. Recipient survival (A) and body weight changes (B) are shown. Numbers of recipients given transplants of BM alone or plus WT or CD18−/− T cells were 7, 11, and 12, respectively, and data are pooled from 2 replicate experiments. (C) Recipients were tracked for in vivo luminescence 10 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of firefly luciferin; data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (D) BMT was set as in panels A and B, and BALB/c recipients of WT or CD18−/− T cells were killed 2 weeks after transplantation. Splenocytes of each recipient were assayed directly for cytotoxicity without in vitro restimulation. The activity of cytolytic effectors was measured in a 4- to 5-hours cytotoxic assay against A20 or Yac-1 at an E/T ratio of 100:1. The data represent the means (± 1 SD) of percentage of specific killing from 3 to 4 replicate mice each group, and the percentage of killing is normalized based on the number of total T cells in the spleen. The assay was run in triplicate with less than 5% SE, and data represent 1 of 2 replicate experiments. (E) Splenocytes from WT or CD18−/− B6 donors were stimulated with IL-2 for 3 days and used as effector cells to kill Yac-1 (NK-sensitive targets) or A20 cells an E/T ratio of 100:1. The data represent the means (± 1 SD) of percentage of specific killing from 2 replicate mice each group, and triplicate wells were set in vitro with less than 5% SE.

Splenocytes from recipients of either WT or CD18−/− T cells had similar abilities to kill A20 (Figure 6D). Both donor T cells and NK cells can mediate GVL activity against A20 cells, and transplantation with TCD BM plus enriched T cells supports the theory that the GVL effect was resulted from engrafted T cells. However, contaminating NK cells in the donor graft might still contribute to anti-A20 activity. To test this possibility, we measured the ability of recipient splenocytes to kill Yac-1 cells (the NK-sensitive target), and found that splenocytes from the recipients of WT T cells were able to lyse Yac-1 targets, although at a low level. In contrast, splenocytes from the recipients of CD18−/− T cells could not lyse Yac-1 targets at all (Figure 6D), suggesting the function of CD18−/− NK cells was impaired. To further evaluate the function of WT and CD18−/− NK cells, we directly measured the killing activity of NK cells against Yac-1 and A20 targets in vitro, and found that IL-2–activated NK cells from CD18-deficient mice had minimal killing to Yac-1 and not at all to A20 cells (Figure 6E). These results indicate that the GVL effect against A20 was mediated by CD18 null T cells rather than NK cells.

Discussion

In the current study, we found that T cells without CD18 are severely impaired in the induction of GVHD. Our data indicate that blockade of CD18 by using CD18−/− donor T cells is substantially better than blockade of LFA-1 with its specific mAb.25,26 We interpret that the different outcome is due to complete versus incomplete blocking LFA-1 signal, as it is conceivable that complete blockade is very difficult to achieve with an antibody in vivo. In support of this conclusion, Kess et al reported that 2% to 16% of CD18 gene expression is sufficient for CD4 T cell–induced pathology in a murine model of psoriasis in CD18 hypomorphic mice.7 Furthermore, coblockade of LFA-1 and ICAM-1 with mAbs specific for both molecules increases the efficacy in the prevention of GVHD or graft rejection compared with either mAb alone.26,27 The current study also shows that CD18−/− T cells are less pathogenic than ICAM-1−/− T cells in the induction of GVHD observed by others.25,28 This is likely because other ligands of LFA-1, (ie, ICAM-2 and ICAM-3), may also contribute to GVHD development.

LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18) is an essential component of the immunologic synapse,3 and can also provide costimulatory signals to T cells;4 thus, it plays a critical role in T-cell activation.1 Therefore, diminished ability of CD18−/− T cells in the induction of GVHD could be due to defects in T-cell activation, expansion, and/or effector function. To test the possibility, we compared the number of WT and CD18−/− donor T cells in recipient spleens after transplantation, and found that the level of expansion was similar for these 2 types of T cells early after cell transfer (Figure 3A,B). However, more CD18−/− donor T cells accumulated in recipient blood and spleen at a later time point than WT donor T cells (Figure 3C). Higher numbers of CD18−/− T cells in secondary lymphoid organs likely resulted from fewer those of T cells migrating into other target organs and improved T-cell reconstitution.

The levels of several cytokines were similar in the sera of recipients that were given transplants of WT or CD18−/− T cells, indicating normal activation/function of CD4 cells in the absence of CD18 (Figure 4). Furthermore, CD18−/− T cells were able to reject allogenetic tumor similarly to WT T cells during the first 3 to 4 weeks after BMT (Figure 6), suggesting cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) function of CD18−/− T cells was largely intact. This evidence pointed out that the defect in T-cell activation did not seem to be the major contributor to the diminished pathogenicity of CD18−/− T cells in the development of GVHD.

Considering that LFA-1 is a core component of the immunologic synapse and an important costimulatory molecule,1 it was unexpected to observe a minimal or no defect in alloresponse for CD18−/− T cells in vivo, although the data are consistent with previous report that CD18−/− T cells had essential normal response to hapten antigen in vivo.10 We reason that the high strength of antigen stimulation overcomes the requirement of LFA-1 for T-cell activation under the circumstance in the current study. T-cell–proliferative responses to alloantigen were absent in CD18−/− T cells when using a standard mixed lymphocyte reaction where allogeneic splenocytes were used as APCs,14 but alloantigen-specific proliferation was partially restored when mature allogeneic DCs were used as APCs.10 It is a consensus view that the alloresponse under GVHD development is primarily induced by host mature DCs,29 and that T-cell stimulation is generally stronger in vivo than in vitro under the same T-cell receptor (TCR) ligation. Thus, the virtually normal response of CD18−/− T cells to alloantigens in vivo (Figures 3,4) indicate that β2 integrins are not absolutely required for adequate T-cell activation, expansion, and effector functions, which is also supported by a recent study showing that the contact efficiency between T cells and DCs was unaffected by the absence of LFA-1 in vivo.30

Development of GVHD requires donor T-cell infiltration into target organs including gut, liver, lung, and skin. Since CD18−/− T cells showed activation, expansion, and effector functions similar to those of WT donor T cells, the diminished ability of CD18−/− T cells in the induction of GVHD may reasonably be attributed to the defect in T-cell infiltration of target organs. Indeed, we found that many fewer CD18−/− T cells migrated into recipient small intestine and resulted in significantly less tissue injure compared with WT T cells (Figure 5). Our findings are in line with decreased numbers of T cells in intestinal tissue in CD18−/− mice.31 Moreover, murine colitis is severely attenuated when LFA-1/ICAM interactions are blocked or absent before onset of disease.32,33 A recent study demonstrated that CD18−/− CD4+ T cells primed in the intestinal secondary lymphoid organs were unable to up-regulate the intestinal-specific trafficking molecules α4β7 and CCR9. Interestingly, the defect in trafficking of CD18−/− T cells to the intestinal lamina propria persists even under conditions of equivalent activation and intestinal-tropic differentiation, implicating a role for CD18 in the trafficking of activated T cells into intestinal tissues independent of activation status.34

We also found that less liver pathology existed in the recipients of CD18−/− T cells than in recipients of WT cells 3 weeks after transplantation (Figure 5A,B). However, at the same time, even higher numbers of CD4 and CD8 T cells were observed in the recipients of CD18−/− T cells than in recipients of WT cells (Figure 5C). As tissue injure is an accumulating process, we hypothesize that CD18 plays a role only in the initial T-cell trafficking into recipient liver, whereas other regulators of T-cell trafficking, such as inflammatory chemokines, might become more important during the further development of hepatic GVHD.13 Thus, we postulate that a delayed infiltration by donor CD18−/− T cells resulted in less liver disease. Our findings are consistent with prior reports that blocking LFA-1/ICAM-1 interaction with specific mAb alone or in combination showed a significant reduction in systemic including hepatic GVHD.26,35 However, these data are contrast with work using ICAM-1−/− mice as donors in allogeneic BMT, in which ICAM-1 deficiency failed to protect recipients from developing systemic GVHD. Rather, ICAM-1−/− T cells caused significantly higher clinical scores and more severe hepatic GVHD compared with WT controls.28,36 These results suggest that ICAM-1−/− mice may develop compensatory pathways of T-cell recruitment that are operative in some target issues.

A major goal for GVHD prevention and therapy is the specific blockade of T-cell activities that mediate GVHD while maintaining the beneficial effects of T-cell–mediated GVL effect. We found that the GVL effect was largely preserved or partially diminished for CD18−/− T cells compared with WT donor T cells, as demonstrated by analysis of recipient survival and bioluminescence imaging of A20 tumor growth (Figure 6A-C). It is possible that donor NK cells might contribute to the GVL effect, but several lines of evidence indicate this possibility was extremely unlikely: (1) a minimal number of NK cells, if any, was included in the donor graft, because NK cells, among other types of cells, were removed from the donor T cells transferred into the recipient; and (2) splenocytes from recipients of WT and CD18−/− cells had comparable killing activity to A20. Splenocytes from recipients of WT cells killed Yac-1 targets at a low level, but those of CD18−/− cells did not kill the Yac-1 target at all (Figure 6D); and (3) IL-2–activated NK cells from WT mice killed Yac-1 targets at a relative high level and killed A20 at a low level. IL-2–activated NK cells from CD18−/− mice killed Yac-1 targets at a low level, but did not kill A20 targets at all (Figure 6E). Impaired function of CD18-deficient NK cells was consistent with our previously published work.37 Therefore, we conclude that the residual GVL effect against A20 in the recipients of CD18−/− cells was mediated by CD18 null T cells but not by NK cells.

A20 B-cell lymphoma cells initially grow in the lung and then tend to form infiltrates in lympho-hematopoietic organs, including liver, spleen, lymph node, and BM. We speculate that the GVL activity of CD18−/− T cells is due to intact or even increased accumulation of these cells at these sites, as seen in the liver and spleen on week 3. However, the partially diminished ability to reject tumor likely reflects reduced CTL function of CD8+ T cells without CD18, as suggested by a prior study showing that targeting LFA-1 and CD154 with specific antibodies interferes with the in vivo development of CD8+ cytolytic effectors after hepatocyte transplantation.38 Alternatively, it is also possibly due to reduced infiltration of donor T cells in a particular site (ie, marrow) in the absence of CD18.

In summary, the absence of β2 integrin on alloreactive T cells resulted in significantly less GVHD morbidity and mortality, and alterations in T-cell trafficking in the gut and liver are the most likely mechanism. Moreover, T-cell activation and function and GVL effect were largely intact in the absence of β2 integrin. This provides the rationale for targeting the β2 integrin, possibly in combination with other integrin or chemokine receptor antagonists as a safe therapeutic approach in GVHD.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fei Guo and Francisca Beato for making luc/neo-transduced A20 cell lines, Doris Wiener for assistance in lab management, and Aleksandra Petrovic for demonstrating us the method to isolate lymphocytes from mouse intestine. We are grateful for the technical assistance provided by Flow Cytometry Core Facility at the Moffitt Cancer Center.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants AI 63553 and CA 118116 (to X.-Z.Y.), and AI 51693 (to C.A.). X.-Z.Y. is a recipient of a New Investigator Award supported by the American Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation. This work was also supported in part by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft in the SFB 497/TP C7 (to K.S.-K.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: Y.L. performed research, collected and analyzed data; C.L. performed pathologic analysis; J.Y.D. contributed to research design, interpreted data and revised the manuscript; B.Z. performed the CTL assays; T.P. contributed vital new reagent, interpreted data, and revised the manuscript; K.S.-K. contributed vital new reagent and interpreted data; C.A. contributed to research design, interpreted data and revised the manuscript; and X.-Z.Y. designed research, performed research, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Xue-Zhong Yu, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Mailbox SRB-2, 12902 Magnolia Dr, Tampa, FL 33612-9497; e-mail: yuxz@moffitt.usf.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal