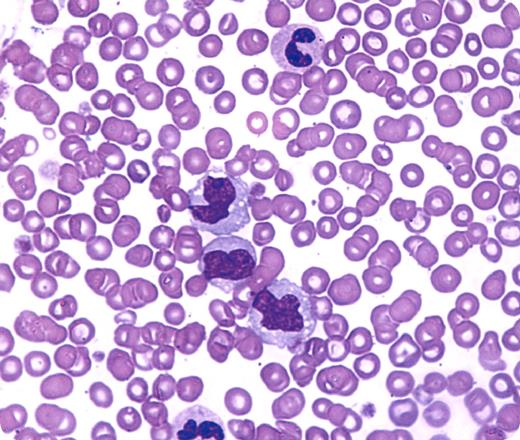

A 59-year-old man was told that he had leukemia that would not be treated. He asked for another opinion. Over the previous 6 months, he had experienced mild weakness, occasional fever, and slight weight loss. He had no other medical problems, and the family history was noncontributory. Examination showed slight pallor and a palpable spleen tip. The patient's hemoglobin count was 112 g/L; white blood cell count, 24×109/L; and platelet count, slightly low. Both hematology specialists who examined the man diagnosed chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. The peripheral blood smear shown above supported this diagnosis by revealing increased monocytes and a pseudo–Pelger-Huet cell.

Essential to this diagnosis is the exclusion of other disorders that are associated with monocytosis, some of which are curable or highly treatable. At city hospitals in the mid-20th century, monocytosis was most often caused by chronic infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, and subacute bacterial endocarditis. Other causes of monocytosis include chronic inflammation, underlying malignancies, autoimmune diseases, parasites, postsplenectomy states, and other marrow disorders.

To the patient's dismay, the second consultant agreed with the recommendation for no specific treatment. Although newer drugs are available for this type of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative process, watch-and-wait management is often appropriate, especially in subjects with few symptoms and no transfusion requirements.

A 59-year-old man was told that he had leukemia that would not be treated. He asked for another opinion. Over the previous 6 months, he had experienced mild weakness, occasional fever, and slight weight loss. He had no other medical problems, and the family history was noncontributory. Examination showed slight pallor and a palpable spleen tip. The patient's hemoglobin count was 112 g/L; white blood cell count, 24×109/L; and platelet count, slightly low. Both hematology specialists who examined the man diagnosed chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. The peripheral blood smear shown above supported this diagnosis by revealing increased monocytes and a pseudo–Pelger-Huet cell.

Essential to this diagnosis is the exclusion of other disorders that are associated with monocytosis, some of which are curable or highly treatable. At city hospitals in the mid-20th century, monocytosis was most often caused by chronic infections such as tuberculosis, pneumonia, and subacute bacterial endocarditis. Other causes of monocytosis include chronic inflammation, underlying malignancies, autoimmune diseases, parasites, postsplenectomy states, and other marrow disorders.

To the patient's dismay, the second consultant agreed with the recommendation for no specific treatment. Although newer drugs are available for this type of myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative process, watch-and-wait management is often appropriate, especially in subjects with few symptoms and no transfusion requirements.

Many Blood Work images are provided by the ASH IMAGE BANK, a reference and teaching tool that is continually updated with new atlas images and images of case studies. For more information or to contribute to the Image Bank, visit www.ashimagebank.org.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal