Abstract

The fact that you can vaccinate a child at 5 years of age and find lymphoid B cells and antibodies specific for this vaccination 70 years later remains an immunologic enigma. It has never been determined how these long-lived memory B cells are maintained and whether they are protected by storage in a special niche. We report that, whereas blood and spleen compartments present similar frequencies of IgG+ cells, antismallpox memory B cells are specifically enriched in the spleen where they account for 0.24% of all IgG+ cells (ie, 10-20 million cells) more than 30 years after vaccination. They represent, in contrast, only 0.07% of circulating IgG+ B cells in blood (ie, 50-100 000 cells). An analysis of patients either splenectomized or rituximab-treated confirmed that the spleen is a major reservoir for long-lived memory B cells. No significant correlation was observed between the abundance of these cells in blood and serum titers of antivaccinia virus antibodies in this study, including in the contrasted cases of B cell– depleting treatments. Altogether, these data provide evidence that in humans, the two arms of B-cell memory—long-lived memory B cells and plasma cells—have specific anatomic distributions—spleen and bone marrow—and homeostatic regulation.

Introduction

Long-lived memory B cells and specific antibodies have been reported to persist in the body for decades after specific vaccination.1-3 One of the central questions concerning this phenomenon concerns the maintenance of this memory in the absence of repeated stimulations with the original vaccine. Experiments in mice suggested that the survival of memory B cells depended neither on constant cell proliferation nor on the presence of the immunizing antigen.4,5 It was therefore assumed that these cells remain quiescent for long periods of time, but nonetheless react very rapidly if they encounter the immunizing antigen. It has also been suggested that the presence of specific serum antibodies is directly linked to the presence of the corresponding memory B cells. In this model, each new antigenic stimulation provides bystander T-cell help for the previously generated memory B cells, leading to the differentiation of some of these cells into Ig-secreting plasmocytes.6 An alternative explanation for the continued presence of serum antibodies a long time after the initial pathogen encounter has also been put forward, according to which each vaccination induces both the immediate differentiation of plasmocytes and the formation of long-lived plasma cells.7,8 These memory plasma cells would survive in bone marrow and would be replaced, at a certain rate, by plasmablasts generated in response to new pathogens.9

Smallpox vaccination is considered an ideal model for studies of the basis of long-term cellular and humoral memory.10 Vaccinia virus was successfully used to eradicate variola virus, the etiologic agent of smallpox. As smallpox vaccination was stopped in the mid 1970s and smallpox was eradicated worldwide in 1977,11 we can assume that people have not been re-exposed to the pathogen since then. Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays following in vitro cell stimulation, we studied the maintenance of the vaccinia virus–specific memory B-cell pool in the blood and spleen of healthy individuals, and in those of patients who had undergone B cell–targeted immune interventions. We show here that long-lived memory B cells have their own central reservoir, the spleen, and seem to display their own homeostatic regulation, independent of the presence of the corresponding plasmocytes.

Methods

Viruses

The modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA), which was used as the antigen in the B-cell ELISPOT assay, was amplified in chicken embryo fibroblasts and purified by centrifugation on a sucrose cushion. Alternatively, highly purified MVA preparations for use in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were produced by centrifugation on 2 successive sucrose gradient cushions. Titers were determined by plaque assays on confluent chicken embryo fibroblast monolayers grown in 6-well tissue culture plates.12

Patients and controls

Approval for this research was granted by the “Comité de protection des personnes Ile-de-France II.” Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The characteristics of the subjects, including age, sex, diagnosis, and medication taken at the time of sample collection, are detailed in Tables S1 to S3 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Nine splenectomized patients (V10 to V18: 4 benign and 3 malignant pancreatic tumors, 2 idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura [ITP]) displayed normal numbers of B cells and had not undergone any chemotherapy. Nine rituximab-treated patients (RTX1 to RTX9) suffered chronic ITP, Sjogren syndrome, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Rituximab regimen is detailed in Table S2 (3 patients received light corticotherapy). Chemotherapy treatment, when given (RTX3, RTX4), was stopped at least 25 months before sample collection, except for V19. Bone marrow samples were obtained from diagnosis aspirations. For all patients, B-cell content and proportions of IgG+ B cells are detailed in Tables S1 to S3. As a control, we obtained blood samples from 16 healthy subjects from the blood bank (Etablissement Français du Sang): 9 vaccinated individuals (35 to 59 years old) and 7 nonvaccinated individuals (all younger than 28 years). Control spleens were retrieved after splenectomy of nonvaccinated patients (microspherocytosis and physical trauma, 7- and 17-year-old, respectively).

Isolation of cells and serum

Spleen samples were recovered in complete medium (RPMI-1640, 100 mU/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin [Invitrogen, Frederick, MD], and 10% fetal calf serum [FCS; HyClone, Logan, UT]) after surgery and were stored at 4°C until processing. In some cases, the entire spleen was maintained under physiological perfusion for 6 hours before cell isolation, as described by Buffet et al,13 with no influence on results. Cell suspensions were obtained by mechanical dissociation in complete medium. Peripheral blood and bone marrow aspirates were collected in heparin or EDTA tubes for cell isolation. In all experiments, mononuclear cells (MNCs) from blood, bone marrow aspirates, or spleen cell suspensions were isolated by centrifugation on a Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient. Red blood cells were lysed and the remaining cells were washed in PBS with 2% FCS and resuspended in complete medium containing 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol. Cell viability after isolation was determined by counting with trypan blue exclusion, and only samples with viability exceeding 90% were considered. In the case of patient RTX6 (B-cell content below 1%), the splenic preparation was enriched for B cells, using the B cell–negative isolation kit (Dynal-Biotech, Oslo, Norway) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Such enrichment was performed to obtain a measurable value in ELISPOT assay. Serum was prepared by clotting blood collected in SST tubes (BD Diagnosis, Franklin Lakes, NJ) or by treating 1 volume of plasma with 1 volume of BC thrombin reagent (Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany) for 10 minutes at room temperature. Serum was then inactivated by heating for 30 minutes at 56°C and frozen in aliquots.

Flow cytometry

Cells were routinely labeled with the following antibodies: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated rabbit F(ab′)2 antihuman IgG (F0056) or the corresponding isotype control (X0929) from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark); phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated antihuman CD27 antibody (clone 1A4-CD27) and PE-cyanin 5.1 (PC5) antihuman CD19 antibody (clone J4.119) from Beckman-Coulter (Fullerton, CA); and allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD19 (clone HIB19) from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). When indicated, labeled cells were incubated with 7-AAD (BD Pharmingen) 10 minutes before analysis to exclude dead cells. Cells were analyzed on a FACScan or FACSCalibur, with CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA).

Memory B-cell assay

This procedure was adapted from that described by Crotty et al.14 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or MNCs were plated at 5 × 105 cells/mL in 24-well (5 × 105 cells) or 6-well (5 × 106 cells) plates, in complete culture medium supplemented with 10 ng/mL pokeweed mitogen extract (PWM, batch 1303H, ICN; MP Biomedicals, Aurora, OH), a 1/10 000 dilution of fixed Staphylococcus aureus, Cowan extract (SAC; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and 6 μg/mL fully phosphothioated CpG (ODN-2006,15 Proligo; Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were cultured for 6 days at 37°C, under an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. They were then washed and used to seed 96-well plates: from each culture well of 5 × 105 cells, 1 of 5 of the cells was used for IgG ELISPOT and 4 of 5 were used for MVA or keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) ELISPOT (Pierce Biochemicals, Rockford, IL). From culture wells of 5 × 106 cells, 1 of 20 was used for IgG ELISPOT and 19 of 20 were used for MVA or KLH ELISPOT. Samples were serially diluted in culture medium, in triplicate, before transfer to ELISPOT plates. Multiscreen 96-well filter plates (MSIPS4510; Millipore, Bedford, MA) were coated by incubation overnight at 4°C with 100 μL of 3 × 108 MVA pfu/mL, 2.5 μg/mL KLH or 10 μg/mL antihuman Ig polyvalent antibody (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). ELISPOT was performed with 1 μg/mL biotinylated goat anti–human IgG Fc (H10015; Caltag Laboratories) followed by 5 μg/mL HRP-conjugated avidin D (Vector Laboratories, Burlingam, CA) and developed using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Sigma-Aldrich). Spots were counted in wells showing more than 3 specific spots, in an ELISPOT reader, with AID software (version 3.5; Autoimmun Diagnostika, Strassberg, Germany). When detected, IgG-secreting cell numbers from the corresponding unstimulated wells (cells cultivated in complete medium alone) were substracted to the values obtained in stimulated cells. Each experiment was conducted in 3 independent wells, and the results are the mean of the 3 ELISPOT values obtained. Data are presented as the percentage of total IgG+ memory B cells specific for vaccinia virus. When no vaccinia virus–specific spot was detectable, a value “less than x” was assigned, with x corresponding to the frequency obtained if one vaccinia-specific spot was detected at the lowest dilution.

ELISA

Maxisorp plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated by incubation overnight at 4°C with 106 MVA pfu/well. Plates were blocked by incubation with 10% FCS in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C. Triplicates of serum samples were serially diluted in PBS-0.05% Tween20 (PBST) and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Plates were washed 4 times in PBST, and were then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti–human IgG Fc (Nordic Immunology, Tilburg, The Netherlands) at a concentration of 2 μg/mL in PBST. Plates were washed 4 times in PBST and incubated with OPD (Sigmafast OPD tablets; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 1.8 N H2SO4, and optical density was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm. The determination of serum titer is detailed in Figure S1.

Statistical methods

Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis 2-sided score test was used to compare the frequency of vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells between blood and spleen and between controls and splenectomized patients, as well as serum titers of vaccinia virus antibody between the different groups studied. For the 23 vaccinated individuals for whom both parameters were known, we estimated the Spearman coefficient of correlation R2 between anti–vaccinia virus antibody titers and the frequency of vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells. All analyses were performed using SAS Software 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells are concentrated in the spleen

We first compared the proportion of memory B cells against vaccinia virus in the blood and spleen several decades after vaccination, in samples obtained from vaccinated (Table 1, V1-V20) or nonvaccinated (Table 1, C1-C9) individuals. The modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) is a replication-deficient strain of vaccinia virus that was tested as a safer vaccine for smallpox vaccination.16 It was used throughout this study for the ELISPOT and ELISA assays to assess cellular and serologic antismallpox/vaccinia virus memory. Blood or splenic mononuclear cells were analyzed by ELISPOT against MVA, after 6 days of in vitro polyclonal stimulation, as described by Crotty et al.14 We determined the proportion of anti–vaccinia virus–specific B cells as the ratio of anti-MVA IgG+ cells to total IgG+ cells (Figure 1A). The members of the vaccinated cohort were aged between 31 and 75 years, whereas the nonvaccinated controls were all younger than 28 years (Table 1). We first confirmed previous results,1 showing that a median of 0.07% of circulating IgG+ memory B cells were specific for vaccinia virus in the blood of individuals vaccinated more than 30 years previously, with the values observed lying between 0.01% and 0.16% (Figure 1B; Table 1). The absence of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in the nonvaccinated controls indicated an absence of cross-reactive responses induced by closely related viruses. We retrieved splenic fragments, mostly from patients who had undergone surgery for a pancreatic tumor (see description of patients in Table S1). Splenic mononuclear cells from 9 patients vaccinated at least 30 years ago, and from 2 nonvaccinated controls (7 and 17 years old) were analyzed with the anti-MVA ELISPOT assay. The proportion of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in the spleen was much higher, at 0.24%, with values ranging from 0.07 to 0.62% (Figure 1B; V10-V18 in Table 1). No vaccinia virus–specific IgG-secreting cells were detected in control culture with unstimulated cells either from blood or from spleen. In 3 patients from whom both splenic and blood samples could be obtained, the proportion of memory B cells in the spleen and blood differed by a factor of 3 to 10 (Figure 1B insert; V10, V13, V18, in Table 1), these differences being observed even in cases in which the frequency of splenic memory B cell was in the lower range (Table 1, V13 and V18).

Serum anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in blood, spleen, and bone marrow

| Individual . | Age, y . | Antivaccinia virus IgG (serum dilution ratio)† . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In blood . | In spleen . | In bone marrow . | |||

| Nonvaccinated | |||||

| C1 | 28 | 0.22 | <0.001* | — | — |

| C2 | 27 | 0.07 | <0.001* | — | — |

| C3 | 24 | nd | <0.013* | — | — |

| C4 | 24 | 0.04 | <0.030* | — | — |

| C5 | 23 | 0.12 | <0.010* | — | — |

| C6 | 20 | 0.08 | <0.004* | — | — |

| C7 | 20 | 0.05 | <0.010* | — | — |

| C8 | 17 | nd | <0.018* | <0.002* | — |

| C9 | 7 | nd | nd | <0.005* | — |

| Median | — | 0.075 | — | — | — |

| Vaccinated | |||||

| V1 | 59 | 0.27 | 0.037 | — | — |

| V2 | 56 | 0.28 | 0.110 | — | — |

| V3 | 53 | 1 | 0.088 | — | — |

| V4 | 53 | 0.38 | 0.112 | — | — |

| V5 | 53 | 0.10 | 0.134 | — | — |

| V6 | 48 | 0.07 | 0.062 | — | — |

| V7 | 48 | 0.49 | 0.010 | — | — |

| V8 | 45 | nd | 0.117 | — | — |

| V9 | 35 | 0.73 | 0.155 | — | — |

| V10 | 75 | 1.16 | 0.047 | 0.456 | — |

| V11 | 74 | 0.53 | nd | 0.157 | — |

| V12 | 66 | ni | nd | 0.309 | — |

| V13 | 59 | 0.40 | <0.012* | 0.068 | — |

| V14 | 58 | 0.29 | nd | 0.301 | — |

| V15 | 57 | nd | nd | 0.616 | — |

| V16 | 53 | nd | nd | 0.230 | — |

| V17 | 45 | 0.21 | nd | 0.238 | — |

| V18 | 31 | ni | 0.031 | 0.088 | — |

| V19 | 53 | 0.68 | 0.022 | — | 0.038 |

| V20 | 47 | 0.10 | 0.067 | — | 0.018 |

| Median | — | 0.380 | 0.067 | 0.238 | — |

| Individual . | Age, y . | Antivaccinia virus IgG (serum dilution ratio)† . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In blood . | In spleen . | In bone marrow . | |||

| Nonvaccinated | |||||

| C1 | 28 | 0.22 | <0.001* | — | — |

| C2 | 27 | 0.07 | <0.001* | — | — |

| C3 | 24 | nd | <0.013* | — | — |

| C4 | 24 | 0.04 | <0.030* | — | — |

| C5 | 23 | 0.12 | <0.010* | — | — |

| C6 | 20 | 0.08 | <0.004* | — | — |

| C7 | 20 | 0.05 | <0.010* | — | — |

| C8 | 17 | nd | <0.018* | <0.002* | — |

| C9 | 7 | nd | nd | <0.005* | — |

| Median | — | 0.075 | — | — | — |

| Vaccinated | |||||

| V1 | 59 | 0.27 | 0.037 | — | — |

| V2 | 56 | 0.28 | 0.110 | — | — |

| V3 | 53 | 1 | 0.088 | — | — |

| V4 | 53 | 0.38 | 0.112 | — | — |

| V5 | 53 | 0.10 | 0.134 | — | — |

| V6 | 48 | 0.07 | 0.062 | — | — |

| V7 | 48 | 0.49 | 0.010 | — | — |

| V8 | 45 | nd | 0.117 | — | — |

| V9 | 35 | 0.73 | 0.155 | — | — |

| V10 | 75 | 1.16 | 0.047 | 0.456 | — |

| V11 | 74 | 0.53 | nd | 0.157 | — |

| V12 | 66 | ni | nd | 0.309 | — |

| V13 | 59 | 0.40 | <0.012* | 0.068 | — |

| V14 | 58 | 0.29 | nd | 0.301 | — |

| V15 | 57 | nd | nd | 0.616 | — |

| V16 | 53 | nd | nd | 0.230 | — |

| V17 | 45 | 0.21 | nd | 0.238 | — |

| V18 | 31 | ni | 0.031 | 0.088 | — |

| V19 | 53 | 0.68 | 0.022 | — | 0.038 |

| V20 | 47 | 0.10 | 0.067 | — | 0.018 |

| Median | — | 0.380 | 0.067 | 0.238 | — |

nd indicates not done; ni, not interpretable (patient receiving intravenous Ig at the time of sample collection); and —, not applicable.

Maximum estimate for individuals for whom memory B cells were undetectable (“Methods”).

Dilution factor with respect to the positive control, see definition in “Methods.”

Vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells are enriched in the spleen and decreased in blood after splenectomy or rituximab treatment. ELISPOT assays were performed after 6 days of in vitro polyclonal stimulation of mononucleated cells. (A) ELISPOT showing a 10-fold enrichment of antivaccinia memory B cells in the spleen. MVA, anti-IgG, or an unrelated antigen (KLH) were used as coating antigens. Blood and spleen samples from patient V10 (Table 1). Shown is one representative ELISPOT well of 3, corresponding to the indicated dilution for each antigen. (B) Frequency of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in blood and spleen, determined by ELISPOT assay. The insert shows data from 3 patients (V10, V13, V18, Table 1) for whom both blood and spleen were analyzed. (C) Frequency of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells determined by ELISPOT assay in blood of splenectomized (SPL) and rituximab-treated (RTX) patients, compared with healthy donors (control, same samples as in B). Bold lines indicate the median values for groups with sample size more than 5. Dashed symbols correspond to maximum estimates for individuals for whom specific memory B cells were undetectable (“Memory B-cell assay”). P values are determined by a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis 2-sided test.

Vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells are enriched in the spleen and decreased in blood after splenectomy or rituximab treatment. ELISPOT assays were performed after 6 days of in vitro polyclonal stimulation of mononucleated cells. (A) ELISPOT showing a 10-fold enrichment of antivaccinia memory B cells in the spleen. MVA, anti-IgG, or an unrelated antigen (KLH) were used as coating antigens. Blood and spleen samples from patient V10 (Table 1). Shown is one representative ELISPOT well of 3, corresponding to the indicated dilution for each antigen. (B) Frequency of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in blood and spleen, determined by ELISPOT assay. The insert shows data from 3 patients (V10, V13, V18, Table 1) for whom both blood and spleen were analyzed. (C) Frequency of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells determined by ELISPOT assay in blood of splenectomized (SPL) and rituximab-treated (RTX) patients, compared with healthy donors (control, same samples as in B). Bold lines indicate the median values for groups with sample size more than 5. Dashed symbols correspond to maximum estimates for individuals for whom specific memory B cells were undetectable (“Memory B-cell assay”). P values are determined by a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis 2-sided test.

Variable impact of rituximab-induced B-cell depletion on anti–vaccinia virus memory B-cell survival

It has been reported that the circulation is depleted of most of its B cells following treatment with rituximab, a B-cell–depleting anti-CD20 antibody. However, the extent of this depletion seems to be more variable in lymphoid organs.17-19 B-cell recovery in the blood starts approximately 6 months after the end of the treatment, with normal levels reached after 12 to 20 months. We analyzed the blood of 5 patients treated with rituximab 25 to 39 months previously (Table 2; Figure 1C). No circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells were detected in 2 patients (RTX3: < 0.007%, RTX5: < 0.04%), whereas such cells were detected in 2 others (RTX4, RTX1), albeit at a low frequency (0.01% and 0.04%, respectively). Surprisingly, in the last patient (RTX2), memory B cells specific for vaccinia virus were found 26 months after rituximab treatment (RIT; 2 cycles, see description of patients in Table S2) at a frequency much higher (0.32%) than that observed in the blood of healthy individuals analyzed several decades after vaccination. An increase in serum B cell–activating factor (BAFF) concentration has been reported after RIT in some patients.20 Serum BAFF level was normal in patient RTX2 (not shown), leaving us with no clear explanation for these findings. Thus, most patients treated with rituximab displayed a lower frequency of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in their blood.

Serum anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in rituximab-treated (RTX) patients

| Patient . | Age at sample collection, y . | Time after rituximab, mo . | Anti-vaccinia virus IgG, serum dilution ratio . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In blood . | In spleen . | ||||

| RTX1 | 83 | 39 | 0.12 | 0.044 | — |

| RTX2 | 61 | 26 | 0.84 | 0.317 | — |

| RTX3 | 55 | 29 | 0.32 | <0.007* | — |

| RTX4 | 45 | 25 | 0.05 | 0.010 | — |

| RTX5 | 42 | 32 | 0.25 | <0.041* | — |

| RTX6 | 79 | 3 | ni | —† | 0.140 |

| RTX7 | 70 | 6 | ni | —† | 0.063 |

| RTX8 | 62 | 15 | 0.47 | —† | 0.064 |

| RTX9 | 67 | 2 + 36‡ | 0.40 | 0.015 | — |

| Patient . | Age at sample collection, y . | Time after rituximab, mo . | Anti-vaccinia virus IgG, serum dilution ratio . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In blood . | In spleen . | ||||

| RTX1 | 83 | 39 | 0.12 | 0.044 | — |

| RTX2 | 61 | 26 | 0.84 | 0.317 | — |

| RTX3 | 55 | 29 | 0.32 | <0.007* | — |

| RTX4 | 45 | 25 | 0.05 | 0.010 | — |

| RTX5 | 42 | 32 | 0.25 | <0.041* | — |

| RTX6 | 79 | 3 | ni | —† | 0.140 |

| RTX7 | 70 | 6 | ni | —† | 0.063 |

| RTX8 | 62 | 15 | 0.47 | —† | 0.064 |

| RTX9 | 67 | 2 + 36‡ | 0.40 | 0.015 | — |

ni indicates not interpretable (patient receiving intravenous Ig at the time of sample collection); and —, not applicable.

Maximum estimate for individuals for whom memory B cells were undetectable.

B-cell depletion precluded blood analyses.

Patient was splenectomized 2 months after rituximab treatment. Blood was collected 36 months after splenectomy.

Some splenic anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells can resist rituximab treatment

Given the highly variable pattern of memory B-cell recovery after RIT, and assuming that the spleen could act as a major reservoir for these cells, we decided to determine the frequency of residual memory B cells in the spleen after RIT. We focused on 3 cases of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) who underwent splenectomy after a failure to respond to treatment. One patient (RTX6, Table 2) was splenectomized 3 months after RIT. No B cells were detected in his blood, and the percentage of B cells in the spleen was very low (around 0.1%). These cells were found to be almost exclusively IgG+ CD27+ (Figure 2), thus suggesting a memory phenotype. After in vitro stimulation, anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells were detected, amounting to 0.14% of total IgG+ B cells (Table 2). The second patient (RTX7, Table 2) underwent splenectomy 6 months after the end of RIT. B cells were beginning to reappear in his blood (1.6%, vs 10% in controls) and spleen (10%, vs 40% in controls). Memory B cells against vaccinia virus were not detectable in his blood and amounted to 0.06% in his spleen. In the third patient (RTX8, Table 2) in which the spleen was retrieved 15 months after the end of RIT, B cells recovered to normal values in blood and spleen (Table S2) but vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells could be found only in the spleen at a frequency of 0.06% of total IgG-secreting cells. These 3 cases evoke that a small pool of splenic anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells (a few tens of thousands memory B cells) has resisted RIT along with other IgG+ switched B cells. As the spleen replenishes with newly formed IgG+ B cells, this pool may tend to dilute itself.

Rituximab-resistant splenic B cells are CD27+ IgG+. The B-cell content was analyzed at the time of splenectomy, 3 months after 4 cycles of rituximab (patient RTX6, Table 2). (A) CD19 and CD27 staining of blood PBMCs. (B) Staining of the splenic MNCs. From left to right: 7-AAD staining; CD19 and CD27 staining gated on 7-AAD–negative cells; IgG and isotype control staining of CD19+ 7-AAD–negative cells. Eighty percent of the splenic CD19+ B cells were of the IgG+CD27+ memory phenotype.

Rituximab-resistant splenic B cells are CD27+ IgG+. The B-cell content was analyzed at the time of splenectomy, 3 months after 4 cycles of rituximab (patient RTX6, Table 2). (A) CD19 and CD27 staining of blood PBMCs. (B) Staining of the splenic MNCs. From left to right: 7-AAD staining; CD19 and CD27 staining gated on 7-AAD–negative cells; IgG and isotype control staining of CD19+ 7-AAD–negative cells. Eighty percent of the splenic CD19+ B cells were of the IgG+CD27+ memory phenotype.

Splenectomy affects the circulating long-lived memory B-cell pool

If long-lived memory B cells are principally maintained in the spleen, then the frequency of these cells should be significantly lower in patients who were splenectomized several years ago. We collected blood samples from 5 patients, who had undergone splenectomy 7 to 50 years previously (see description of patients in Table S3). The levels of circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells were all below the median of the control values (Figure 1C; Table 3, SPL4: no detectable anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells, SPL1: 0.01%, SPL3: 0.009%, SPL2, for which small accessory spleens were detected: 0.04%, and SPL5: 0.06%). These results suggest that splenectomy may lead to a consistent loss of long-lived memory B cells and that this deficiency can persist even several decades after the surgical procedure. Nevertheless, these cells can still be found, albeit at diminished levels, in the blood of most of these patients, suggesting the existence of other minor storage sites outside the spleen.

Serum anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in splenectomized (SPL) patients

| Patient . | Age at sample collection, y . | Years after splenectomy . | Anti–vaccinia virus IgG, serum dilution ratio . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells in blood . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPL1 | 60 | 50 | 1.10 | 0.010 |

| SPL2 | 59 | 44 | 0.20 | 0.041 |

| SPL3 | 52 | 7 | 0.34 | 0.009 |

| SPL4 | 46 | 35 | 0.28 | <0.009* |

| SPL5 | 35 | 30 | 0.01 | 0.062 |

| Patient . | Age at sample collection, y . | Years after splenectomy . | Anti–vaccinia virus IgG, serum dilution ratio . | % vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells in blood . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPL1 | 60 | 50 | 1.10 | 0.010 |

| SPL2 | 59 | 44 | 0.20 | 0.041 |

| SPL3 | 52 | 7 | 0.34 | 0.009 |

| SPL4 | 46 | 35 | 0.28 | <0.009* |

| SPL5 | 35 | 30 | 0.01 | 0.062 |

Maximum estimate for individuals for whom memory B cells were undetectable.

Further evidence to support this hypothesis is provided by the case of a rituximab-treated patient who underwent splenectomy 2 months after 4 cycles of RIT and who was analyzed 36 months after splenectomy. A small proportion of circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells could be detected in this patient (RTX9: 0.02%, Table 2).

In 2 cases in which it was possible to analyze a bone marrow sample not contaminated with malignant cells or blood, we detected no significant enrichment of anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells over average values for blood (V19: 0.04%, V20: 0.02%, Table 1).

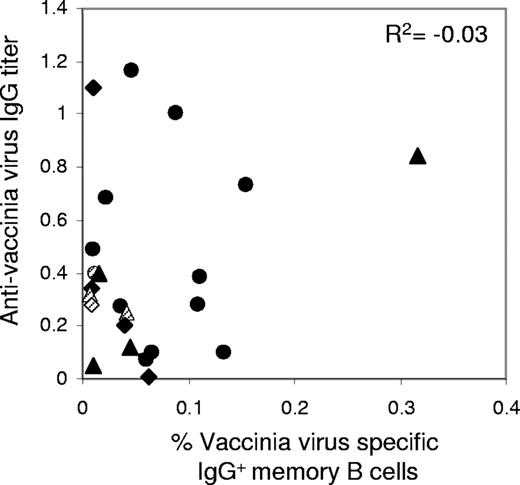

No significative correlation between vaccinia virus–specific serum antibody titers and blood memory B cells

We estimated the correlation between the proportion of memory B cells and the level of specific antibodies against vaccinia virus, using ELISA to determine serum anti–vaccinia virus antibody titers in the blood of most of the subjects analyzed in this study (Tables 1,Table 2–3). A large proportion of the patients vaccinated more than 30 years ago had measurable levels of anti–vaccinia virus antibodies, consistent with the findings of previous reports.1-3 We took a value of 0.075, the median value for nonvaccinated individuals, as the threshold below which levels of IgG against vaccinia virus were considered negative (Table 1; Figure S1). Three patients with no anti–vaccinia virus antibodies were found to have vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells in their blood (V6, Table 1 and RTX4, SPL5, Tables 2–3). Conversely, in 3 patients with a reasonably high level of anti–vaccinia virus antibodies, no circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells could be detected in their blood (V13, Table 1 and SPL4, RTX3, Tables 2–3). No significative correlation was found in this study between the proportion of memory B cells and the titer of antibodies specific for vaccinia virus (Figure 3, for n = 23 individuals, R2 = − 0.03, P = .88).

No correlation between anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and memory B cells in blood. Anti–vaccinia virus IgG titer and anti–vaccinia virus memory B-cell frequency from the same blood samples were compared. Data are from n = 23 individuals including 12 control individuals (circles), 5 splenectomized patients (diamonds), and 6 rituximab-treated patients (triangles) for whom both values were measurable. Dashed symbols correspond to maximum estimates for individuals for whom memory B cells were undetectable (“Memory B-cell assay”) and anti–vaccinia virus serum titer were positive. Shown is the Spearman coefficient of correlation R2 for the n = 23 samples (P = .88).

No correlation between anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and memory B cells in blood. Anti–vaccinia virus IgG titer and anti–vaccinia virus memory B-cell frequency from the same blood samples were compared. Data are from n = 23 individuals including 12 control individuals (circles), 5 splenectomized patients (diamonds), and 6 rituximab-treated patients (triangles) for whom both values were measurable. Dashed symbols correspond to maximum estimates for individuals for whom memory B cells were undetectable (“Memory B-cell assay”) and anti–vaccinia virus serum titer were positive. Shown is the Spearman coefficient of correlation R2 for the n = 23 samples (P = .88).

Discussion

We studied the persistence of vaccinia virus–specific memory B cells in the blood and spleen of healthy individuals and of patients who had undergone B cell–targeted immune interventions, namely splenectomy, or anti-CD20–mediated B-cell depletion.

In individuals vaccinated with the vaccinia virus during their childhood (ie, more than 30 years before this study) approximately 0.24% of splenic IgG+ B cells recognize this pathogen. This proportion is significantly higher than that for the blood (approximately 0.07%, consistent with previous reports1,3 ). Taking into account the size of the blood and splenic B-cell compartments (approximately 5 × 108 and 4 × 1010 B cells, respectively, with 10% to 20% IgG+ B cells), there are, on average, around 0.5 to 1 × 105 memory B cells against vaccinia virus circulating in the blood of vaccinated individuals, and 1 to 2 × 107 such cells in the spleen. Assuming that all pathogens display similar numbers of immunodominant B-cell epitopes, thereby engaging similar numbers of memory B cells, this suggests that the splenic B-cell compartment has an overall memory against 102 to 103 different pathogens. The values proposed for the repertoire of long-lived plasma cells in humans are of the same order of magnitude.21 It has been suggested that some long-lived plasma cells may be regularly replaced by newly formed plasmablasts, although it remains unclear how this replacement takes place.9 A similar turnover may occur for memory B cells, but again, we know little of the basic mechanism of memory formation and the signals conferring on these cells a shorter or longer existence within the individual.

We could not study lymph nodes or Peyer patches from vaccinated individuals, raising questions about the possibility of other secondary lymphoid organs constituting an additional reservoir for long-lived memory B cells. There was a severe reduction, although not a complete loss, of circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells in most splenectomized patients. This suggests that these cells survive as such in the blood or that there are other accessory niches outside the spleen. Rituximab, a chimeric human/mouse anti-CD20 antibody, has become a major treatment for B cell–related lymphomas and autoimmune disorders. Two to 4 years after RIT, most patients presented much lower levels of circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells. Analysis of the spleen a few months after RIT showed the presence of residual B cells, with the IgG+ phenotype only, including a small proportion of long-lived memory B cells, despite the total absence of circulating B cells. Strikingly, a low level of circulating anti–vaccinia virus memory B cells was also observed in one patient, 3 years after a splenectomy performed 2 months after the completion of rituximab treatment. Since B-cell depletion was still complete in the blood at the time of splenectomy, this unique case strengthens the view that there are other storage sites for memory B cells, but that these sites do not seem to compensate quantitatively for the absence of the spleen. Bone marrow has been identified as a preferential niche for long-lived plasma cells and for some memory T and B cells.7,8,22,23 We did not detect any specific enrichment of vaccinia virus memory B cells in the 2 bone marrow samples that we have analyzed. Overall, these results suggest that the spleen is a major niche for long-lived memory B cells but that despite drastic B cell–depleting treatment such as RIT or splenectomy, these cells can slowly reappear in the blood. These treatments therefore do not seem to result in the systematic eradication of the B-cell memory carried by these patients, notably the one related to childhood vaccinations. Consistent with this interpretation, the response to recall antigens seemed to be strongly decreased by rituximab treatment in one study of lymphoma patients,24 whereas this response was found to be preserved in another study.25

The concept of two layers of long-term humoral memory sustained by the existence of long-lived memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells emerged some years ago7,8 and has subsequently been strongly supported by experimental data.26 It has also been proposed that the maintenance of antibodies several decades after a vaccination or an infection was due to a constant production by nonspecific stimulation of memory B cells.6 In the later case, there should be a quantitative correlation between the frequency of memory B cells and the level of serum antibodies. In several reports in which these parameters were analyzed after vaccination or natural infections, the strength of the correlation varied considerably,1,3,27-29 suggesting that bystander stimulation of memory B cells into short-lived plasma cells was unlikely to be a general mechanism. In the present study, in which it was possible to analyze more strongly contrasting situations, no correlation was observed for the 23 patients for whom both serum titers of anti–vaccinia virus antibodies and memory B cells could be determined. In fact, a complete dissociation was observed in several cases, with anti–vaccinia virus antibodies detected in the total absence of the corresponding memory B cells, or memory B cells being present in the absence of the corresponding antibodies. This observation gives additional support to the proposal that long-lived memory B cells and long-lived plasma cells in humans are independent entities, with long-lived plasma cells able to survive for several decades independently of the presence of memory B cells of the same specificity.3,8,30 Nevertheless, B-cell memory does not seem to be a uniform phenomenon and one cannot exclude that some antigen-specific or nonspecific stimulation of long-lived memory B cells could also contribute to the production of antibodies.6,31

Many unanswered questions remain concerning the homeostatic regulation of long-lived memory B cells. If the spleen is indeed, as proposed here, a main reservoir for these cells, then most memory B cells may react only to a specific recall pathogen once it reaches the spleen, whereas the circulating memory B cells and neutralizing antibodies will provide a first line of defense at the beginning of infection.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs B. Ranque and A. Alcaïs for statistical analysis, S. Arguès for assistance with ELISA, Dr Puydupin from the EFS St-Vincent de Paul for providing blood samples, and Dr Alyanakian from Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades for serologic determinations. We thank Q. Gueranger for helpful suggestions, and L. Abel and J. L. Casanova for critical reading of the paper.

This work was supported by the Fondation Princesse Grace, the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (“B-cell memory,” MIIM program), and the Ligue Contre le Cancer (Equipe labellisée). M.M.-M. was supported by successive fellowships from the Fondation de France, the Fondation Singer-Polignac, and the Région Ile-de-France. C.-A.R. is a Research Director at the Center National de la Recherche Scientifique. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Authorship

Contribution: M.M.-M. conducted all the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the paper; A.C., S.W., and A.F. contributed to research and critical discussions; C.S. produced MVA; L.G., O.H., O.B.-R., C.F., J.-O.P., N.A., B.V., A.S., A.B., F.P., J.-M.A., M.M., B.G., and P.B. participated in the selection and collection of patient samples; M.M. and B.G. provided clinical support for the study; C.-A.R. and J.-C.W. share senior scientific responsibility and authorship.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claude-Agnès Reynaud or Jean-Claude Weill, Inserm U783, Université Paris Descartes, Faculté de Médecine, site Necker-Enfants Malades, 156 rue de Vaugirard, 75015 Paris, France; e-mail: reynaud@necker.fr or weill@necker.fr.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal