Abstract

Although hepcidin expression was shown to be induced by the BMP/Smad signaling pathway, it is not yet known how iron regulates this pathway and what its exact molecular targets are. We therefore assessed genome-wide liver transcription profiles of mice of 2 genetic backgrounds fed iron-deficient, -balanced, or -enriched diets. Among 1419 transcripts significantly modulated by the dietary iron content, 4 were regulated similarly to the hepcidin genes Hamp1 and Hamp2. They are coding for Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 all related to the Bmp/Smad pathway. As shown by Western blot analysis, variations in Bmp6 expression induced by the diet iron content have for functional consequence similar changes in Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation that leads to formation of heteromeric complexes with Smad4 and their translocation to the nucleus. Gene expression variations induced by secondary iron deficiency or iron overload were compared with those consecutive to Smad4 and Hamp1 deficiency. Iron overload developed by Smad4- and Hamp1-deficient mice also increased Bmp6 transcription. However, as shown by analysis of mice with liver-specific disruption of Smad4, activation of Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 transcription by iron requires Smad4. This study points out molecules that appear to play a critical role in the control of systemic iron balance.

Introduction

Iron, by virtue of its ability to accept or donate electrons, is essential for many of the biologic reactions carried out by living systems. This same characteristic, however, allows free iron in solution to form highly reactive oxygen species that can oxidize lipids, DNA, and proteins, and lead to cell damage. As there is no physiological means for excreting iron in mammals, systemic iron homeostasis must be maintained by tight regulation of intestinal iron absorption, as well as macrophage and hepatocyte iron release.

Hepcidin has a key role in coordinating the use and storage of iron with iron acquisition.1 It acts by binding to ferroportin, an iron exporter present on the surface of enterocytes, macrophages, and hepatocytes, and induces its internalization and lysosomal degradation.2 The loss of ferroportin from the cell surface prevents iron efflux from intestinal enterocytes, recycling of iron from senescent erythrocytes by macrophages, and iron mobilization from hepatic stores. Hepcidin production is inhibited by iron deficiency anemia and tissue hypoxia,3 which increases iron availability for use in erythropoiesis. By contrast, hepcidin expression is enhanced by dietary or parenteral iron loading,4 thus providing a feedback mechanism to limit intestinal iron absorption. Individuals with mutations in any of the hepcidin (HAMP),5 hemojuvelin (HJV),6 transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2),7 or HFE8 genes have low hepcidin levels despite excessive iron stores. As a consequence, they are unable to effectively repress iron absorption.

Recently, Babitt et al9,10 demonstrated that hepcidin expression was induced by the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway. This pathway involves members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily of ligands that act by binding 2 type I and 2 type II BMP receptors (BMPR-I and BMPR-II). This induces the phosphorylation of BMPR-I by BMPR-II and the activated complex, in turn, phosphorylates a subset of Smad proteins (Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8). The receptor-activated Smads then form heteromeric complexes with the common mediator Smad4, and these translocate to the nucleus where they regulate the transcription of specific targets.11 Hemojuvelin (HJV) was shown to act as a BMP coreceptor in vitro and to facilitate the activation of the BMPR-I/II complex.9 Interestingly, stimulation of BMP signaling by HJV is paralleled by an increase in HAMP expression. Support of the involvement of the BMP signaling pathway in the regulation of hepcidin also comes from the observation that liver-specific disruption of the Smad4 gene in mice leads to reduced hepcidin expression and systemic iron loading.12 These mice are unable to synthesize hepcidin in response to inflammatory stimuli or to iron load. The BMP/Smad4 pathway therefore is critical to hepcidin expression.

There are, however, many open questions. First, there are several BMP molecules that can bind HJV in vitro and regulate hepcidin expression,10,13 but further work is needed to determine which of these BMP molecules is the endogenous regulator in vivo. Second, it is not yet known how iron regulates hepcidin. In particular, whether iron is sensed by molecules forming the hepcidin-regulating BMP/HJV/BMPR complex remains to be elucidated. Third, it is still not known whether hepcidin is a direct or indirect target for BMP and the activated Smad/Smad4 complex. To decipher these important issues, we assessed the liver transcription profiles of 2 strains of wild-type mice fed an iron-deficient or an iron-enriched diet and identified 4 genes that were regulated similarly to hepcidin in that context. Analysis of their expression in Smad4- or Hamp1-deficient mice showed that they were all participating in the Bmp/Smad signaling pathway.

Methods

Wild-type mice fed diets with different iron contents

Male mice of the C57BL/6 (B6) and DBA/2 (D2) backgrounds were purchased from the Center d'Elevage Robert Janvier (Le Genest St-Isle, France) and maintained at the IFR 30 animal facility. Dietary iron deficiency was induced by feeding 5 4-week-old-mice of each strain a diet with virtually no iron content (< 3 mg iron/kg; SAFE, Augy, France) and demineralized water for a period of 3 weeks. Five control animals of each strain received the iron-balanced diet of the same composition (200 mg iron/kg). Dietary iron loading was obtained by feeding five 4-week-old animals of each strain the iron-balanced diet supplemented with carbonyl iron (8.3 g/kg) for 3 weeks. All mice were analyzed at 7 weeks and fasted for 14 hours before they were killed. Experimental protocols were approved by the Midi-Pyrénées Animal Ethics Committee. A total of 30 livers were dissected for RNA isolation, rapidly frozen, stored in liquid nitrogen, and used for genome-wide expression profiling. Serum iron parameters and nonheme iron were quantified as previously described.14

Smad4- and Hamp1-deficient mice

Liver samples from six 4-month-old males with liver-specific disruption of Smad4 and 5 10-week-old Hamp1-deficient males that were subjected to detailed analysis in previous publications12,15 were used here to compare gene expression variations consecutive to lack of functional Smad4 or Hamp1 with those induced by secondary iron deficiency or iron overload. Liver samples from males of the same genetic backgrounds and the same ages as Smad4- and Hamp1-deficient mice, respectively, were used as controls.

RNA isolation, preparation of labeled cRNA, microarray hybridization, and analysis of expression data

Total RNA was extracted and purified using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). RNA quality was checked on RNA 6000 Nano chips using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). RNA samples used for chip experiments all had RNA integrity numbers (RINs)16 greater than 9. Agilent's Low RNA Input Linear Amplification Kit PLUS (One-color) was used to generate fluorescent cRNA. The amplified cyanine 3–labeled cRNA samples were then purified using Qiagen's RNeasy mini spin columns and hybridized to Agilent Whole Mouse Genome Microarrays, 4 × 44 K. Microarray slides were washed and scanned with an Agilent scanner, according to the standard protocol of the manufacturer. Information from probe features was extracted from microarray scan images using the Agilent Feature Extraction software v.9.5.1. Expression data were submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information's (NCBI's) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository and are available under the accession number (GenBank: GSE10421).17 All the analyses were performed using Bioconductor, an open source software for the analysis of genomic data rooted in the statistical computing environment R (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA).18 Normalization between arrays was performed using the quantile method. Genes for which the background-corrected signal intensities were not greater than 2.6 standard deviations above the average background in at least 3 B6 and 3 D2 mice were assumed not to be expressed in the liver and were excluded from further analysis. The R/MAANOVA package implemented in Bioconductor19 was used to perform a 2-way analysis of variance in which the log2-transformed expression level was considered to be a function of diet, strain, and the effects of the interaction between these 2 factors. F tests, based on the James-Stein shrinkage estimates of the error variance, were computed on a gene-by-gene basis and P values obtained by permutation analysis. The proportion of false positives among all the genes initially identified as being differentially expressed (FDR) was assessed using the procedure described by Storey et al.20 When influence of diet on expression levels was significant, t tests were performed to investigate specific effects of iron deficiency and iron enrichment.

Real-time quantitative PCR

All primers (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) were designed using the Primer Express 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) reactions were prepared with Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) and LightCycler 480 DNA SYBR Green I Master reaction mix (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) as previously described14 and run in duplicate on a LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche Diagnostics). For each mouse and transcript, an expression measure was calculated as 2Ct ToI − Ct HPRT, where ToI is the transcript of interest; HPRT, a transcript with stable level between strains, diets, and genotypes, quantified to control for variation in cDNA amounts; and Ct, the cycle number where fluorescence reaches a given threshold. Expression values were log2 transformed, and the contribution of diet (iron deficient, standard, or iron enriched) or genotype (wild type, knockout) in each strain was assessed by analysis of variance followed by Scheffe posthoc tests or by Student t tests, respectively, using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The transcript fold changes following the different dietary conditions or Smad4/Hamp1 disruption were calculated on values obtained by raising 2 to the power n, where n is the mean of the log2-transformed expression measures within each group. Correlations between liver iron and expression values were assessed by nonparametric Spearman rank-order correlation tests.

Western blot analysis

Livers were homogenized in a FastPrep-24 Instrument (MP Biomedicals Europe, Illkirch, France) for 40 seconds at 4 m/s. The lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 8, 1% NP-40) included inhibitors of proteases (1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 10 mg/mL pepstatin A, and 1 mg/mL antipain) and of phosphatases (10 μL/mL phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint-Quentin Fallavier, France). Proteins were quantified using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) based on the method of Bradford. Protein extracts (20 μg for Smad7, 30 μg for phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 and Smad1, and 40 μg for Id1) were diluted in Laemmli buffer (Sigma-Aldrich), incubated for 5 minutes at 95°C, and subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Proteins were then transferred to Westran Clear Signal PVDF membranes (Schleicher and Schuell, Maidstone, United Kingdom). Membranes were blocked with either 5% of dry milk in TBS-T buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.15% Tween 20) for phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 and Id1, or a more stringent buffer (10% dry milk, 1% BSA, 1% NP40, 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS) for Smad1 and Smad7. They were incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibodies to phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (1/1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), Id1 (1/200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and Smad7 (1/500; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or with a mouse polyclonal antibody to Smad1 (1/250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4°C overnight, and washed with TBS-T buffer. Following incubation with a goat anti–rabbit or anti–mouse IgG antibody (1/5000; Cell Signaling Technology) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase, enzyme activity was visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL)-based detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France). Blots were then stripped and reprobed with mouse monoclonal antibody to β-actin (1/20 000; Sigma-Aldrich). Quantification of proteins was calculated by normalizing the specific probe band to β-actin using the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Results

Genome-wide mRNA expression profiling identified only 4 genes regulated similarly to hepcidin by the dietary iron content

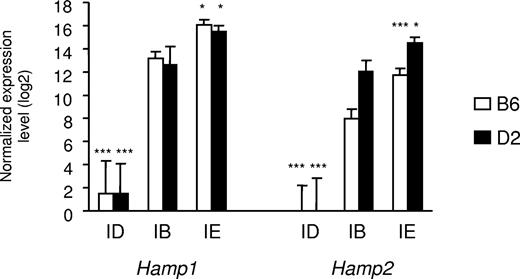

As shown in Table 1, serum iron parameters and liver iron concentration were all significantly affected by the dietary iron content. Whereas, as previously observed, D2 mice fed an iron-balanced diet have slightly higher serum iron parameters than have B6 mice,21 the latter accumulated significantly more iron when fed the iron-enriched diet than did D2 mice. This is particularly noteworthy in the liver (Table 1) and seems to be characteristic of the strain.22 Hamp1 and Hamp2 gene expression was assessed by real-time quantitative PCR. As previously reported, B6 mice fed an iron-balanced diet have lower Hamp2 gene expression than D2 mice fed the same diet.23 As expected, Hamp1 gene expression was virtually abolished by iron deficiency, but was increased approximately 7-fold by iron overload in both B6 and D2 mice. Similarly, Hamp2 gene expression was abolished by iron deficiency and increased by iron overload approximately 5-fold in D2 mice and 13-fold in B6 mice (Figure 1). A total of 30 Agilent microarray hybridizations were performed using mRNA extracted from the livers of 15 B6 and 15 D2 mice (5 mice per diet/strain combination). Two-factor (diet and strain) ANOVA identified 1419 transcripts significantly modulated by the diet iron content (FDR 1°/oo). These transcripts were classified according to their variations similar or opposite to hepcidin mRNAs in iron deficiency and/or iron overload (Table S2). The DAVID annotation tool24,25 was used to search for overrepresentation of functional categories within the different gene groups (Tables S2,S3). Interestingly, there was a significant excess of genes involved in the TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway among those down-regulated by iron deficiency and up-regulated by iron overload as were Hamp1 and Hamp2. Three genes in this functional category had fold changes induced by both diets of 1.5 or more. Two are coding for the bone morphogenetic protein Bmp6 and for an inhibitory Smad (Smad7). Of note, Smad7 is important for the tight regulation of Bmp/Smad signal transduction.26 The third gene, Id1, whose promoter is strongly activated by Bmp in a Smad-dependent manner,27 encodes a negative inhibitor of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins. Besides these genes involved in the TGF-β/BMP signaling pathway, the gene encoding Atoh8, a bHLH protein known to promote neuronal versus glial fate determination in the nervous system,28 was also down-regulated by iron deficiency and up-regulated by iron overload with a fold-change of 1.5 or more.

Iron parameters in B6 and D2 mice fed diets with different iron contents

| Diet . | Serum iron, μM . | TIBC, μM . | Transferrin saturation . | Liver iron concentration, μg iron/g dry weight . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 strain | ||||

| Iron deficient | 7.12 ± 1.90 | 61.12 ± 4.63 | 11 ± 3% | 211 ± 24 |

| Iron adequate | 11.28 ± 1.63 | 39.36 ± 1.98 | 29 ± 4% | 441 ± 85 |

| Iron supplemented | 30.46 ± 1.69 | 30.74 ± 0.94 | 99 ± 7% | 3569 ± 502 |

| D2 strain | ||||

| Iron deficient | 7.32 ± 1.31 | 66.78 ± 8.35 | 11 ± 3% | 224 ± 44 |

| Iron adequate | 22.18 ± 3.37 | 52.20 ± 3.66 | 42 ± 4% | 502 ± 69 |

| Iron supplemented | 31.38 ± 2.80 | 43.62 ± 3.97 | 72 ± 3% | 2353 ± 163 |

| Diet . | Serum iron, μM . | TIBC, μM . | Transferrin saturation . | Liver iron concentration, μg iron/g dry weight . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 strain | ||||

| Iron deficient | 7.12 ± 1.90 | 61.12 ± 4.63 | 11 ± 3% | 211 ± 24 |

| Iron adequate | 11.28 ± 1.63 | 39.36 ± 1.98 | 29 ± 4% | 441 ± 85 |

| Iron supplemented | 30.46 ± 1.69 | 30.74 ± 0.94 | 99 ± 7% | 3569 ± 502 |

| D2 strain | ||||

| Iron deficient | 7.32 ± 1.31 | 66.78 ± 8.35 | 11 ± 3% | 224 ± 44 |

| Iron adequate | 22.18 ± 3.37 | 52.20 ± 3.66 | 42 ± 4% | 502 ± 69 |

| Iron supplemented | 31.38 ± 2.80 | 43.62 ± 3.97 | 72 ± 3% | 2353 ± 163 |

Results are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5 mice per group). Analyses of variance show that, within each strain, the dietary iron content significantly affects serum iron, total iron binding capacity (TIBC), transferrin saturation, as well as hepatic iron concentration (all P values are < .001).

Expression of hepcidin1 (Hamp1) and hepcidin2 (Hamp2) in the liver of mice fed diets with different iron contents. The expression of hepcidin1 and hepcidin2 transcripts was assessed in mice of 2 strains (B6 and D2) fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed, and are expressed as means of 5 samples plus or minus standard deviation. The contribution of diet was assessed by ANOVA, and statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Scheffe posthoc tests. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Expression of hepcidin1 (Hamp1) and hepcidin2 (Hamp2) in the liver of mice fed diets with different iron contents. The expression of hepcidin1 and hepcidin2 transcripts was assessed in mice of 2 strains (B6 and D2) fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed, and are expressed as means of 5 samples plus or minus standard deviation. The contribution of diet was assessed by ANOVA, and statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Scheffe posthoc tests. *P < .05; ***P < .001.

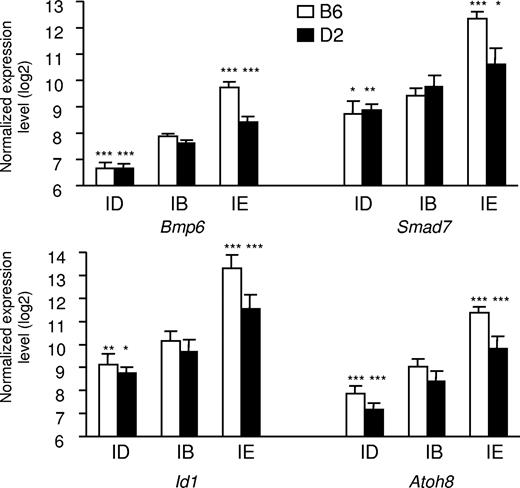

Real-time quantitative PCR confirms microarray data and shows that Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 mRNA levels are highly correlated with the liver iron burden

As shown in Figure 2, real-time quantitative PCR confirms that expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 is up-regulated in mice fed an iron-enriched diet. This up-regulation is significantly larger in B6 mice that have accumulated more iron in their liver than D2 mice. Conversely, the expression of these genes is down-regulated in response to iron deficiency. Pearson correlation coefficients of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 expression with liver iron content are highly significant (0.90, 0.86, 0.91, and 0.86, respectively; all P < .001). Recently, Lin et al showed that iron transferrin regulates hepcidin synthesis in primary hepatocyte culture through hemojuvelin and BMP2/4.29 Although expression of Bmp2 was found modulated by iron overload but not by iron deficiency (Table S3), we did not observe any in vivo modulation of the Bmp4 mRNA by the dietary iron content in our microarray data. Nevertheless, we assessed their expression by real-time quantitative PCR. Interestingly, although expression of Bmp4 was not significantly affected when mice of either the B6 or the D2 genetic background were made iron overloaded or iron deficient (P = .33 and P = .38, respectively), a small but significant increase in the expression of Bmp2 was observed in mice of the B6 strain fed the iron-enriched diet (P = .001). No such increase was observed in the D2 mice that have accumulated less iron in their liver than B6 mice (Figure S1). In addition, no decrease in the expression of Bmp2 was observed in mice of either strain fed the iron-deficient diet. We quantified the Id1 and Smad7 proteins to which antibodies were available in the liver of the 2 mouse strains and observed that Id1 (Figure S2) and Smad7 were modulated by iron not only at the transcript level but also at the protein level.

Expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 in the liver of mice fed diets with different iron contents. The expression of the 4 transcripts was assessed in mice of 2 strains (B6 and D2) fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed, and are expressed as means of 5 samples plus or minus standard deviation. The contribution of diet was assessed by ANOVA, and statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Scheffe posthoc tests. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 in the liver of mice fed diets with different iron contents. The expression of the 4 transcripts was assessed in mice of 2 strains (B6 and D2) fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed, and are expressed as means of 5 samples plus or minus standard deviation. The contribution of diet was assessed by ANOVA, and statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Scheffe posthoc tests. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

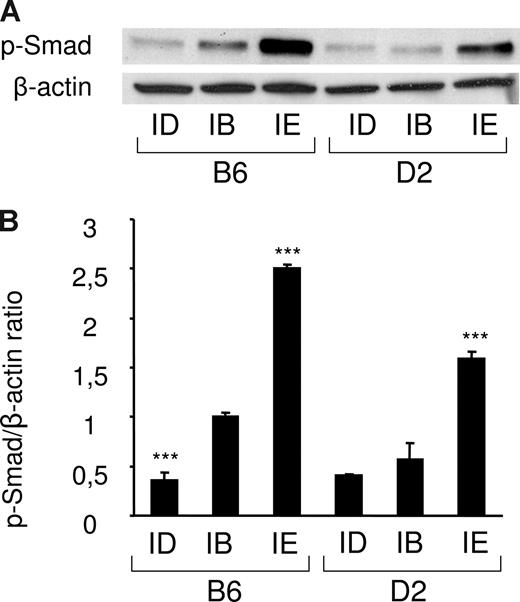

Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation is increased by iron overload and decreased by iron deficiency

Since Bmp6 belongs to the TGF-β superfamily and transmits signal through phosphorylation of Smads,30 we tested whether phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 was significantly modulated in liver extracts of mice fed an iron-deficient or an iron-enriched diet. Total protein lysates from 18 mice were prepared (3 mice per strain/diet combination) and the amount of the phosphorylated forms of Smad1/5/8 in each condition was determined by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3 and Figure S3, the iron-enriched diet induced Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation. This induction was stronger in B6 mice than in D2 mice, which correlates with the higher liver iron burden and Bmp6 expression observed in these mice. Of note, a significant decrease of Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation was also observed in mice fed an iron-deficient diet. The amount of Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in the liver of these mice is therefore correlated with body iron stores and the quantity of Bmp6 transcripts.

Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation is increased by iron overload and decreased by iron deficiency. (A) Liver lysates from mice fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet (n = 3 in each group) were analyzed by Western blot with an antibody to phosphorylated Smad1/5/8. Blots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody to β-actin as loading control. A representative experiment is shown. (B) Chemiluminescence was quantified using Quantity One software to calculate the ratio of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (p-Smad) relative to β-actin. Mean ratios of 3 samples (± SD) are represented on this figure, relative to the mean ratio of the B6 group of mice fed an iron-balanced diet. Statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Student t tests. ***P < .001.

Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation is increased by iron overload and decreased by iron deficiency. (A) Liver lysates from mice fed an iron-deficient (ID), iron-balanced (IB), or iron-enriched (IE) diet (n = 3 in each group) were analyzed by Western blot with an antibody to phosphorylated Smad1/5/8. Blots were stripped and reprobed with an antibody to β-actin as loading control. A representative experiment is shown. (B) Chemiluminescence was quantified using Quantity One software to calculate the ratio of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 (p-Smad) relative to β-actin. Mean ratios of 3 samples (± SD) are represented on this figure, relative to the mean ratio of the B6 group of mice fed an iron-balanced diet. Statistical significant differences relative to the iron-balanced diet were determined by Student t tests. ***P < .001.

Smad4 knockout mice have increased Bmp6 but decreased Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 gene expression

The receptor-activated Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 form heteromeric complexes with Smad4 and these translocate to the nucleus where they regulate the transcription of specific targets. To investigate whether the variations in the mRNA expression of some of these genes could be induced by the observed variations in Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation, we assessed Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, Atoh8, and Hamp1 gene expression in the liver of 6 mutant mice with Cre-loxP–mediated liver-specific disruption of Smad4 and controls of the same genetic background at 4 months of age. Liver-specific disruption of Smad4 was shown to result in accumulation of iron in many organs, in particular the liver.12 As shown in Figure 4A, although liver-specific knockout of Smad4 resulted in markedly decreased expression of Hamp1, it led to increased Bmp6 expression as did the iron-enriched diet. Interestingly, despite the accumulation of iron observed in these mice, Smad4 deficiency resulted in decreased Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 mRNA expression, as did the iron-deficient diet. These results show that the binding partner for the receptor-activated Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 is necessary for activation of Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 transcription by iron in response to Bmp signaling.

Expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, Atoh8, and Hamp1 in the livers of mice with genetic iron overload. Mice with liver-specific knockout of Smad4 (A) or Hamp1 disruption (B) were compared with their respective controls. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed for the statistical analyses. Statistically significant differences relative to the controls were determined by Student t tests. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Geometric means (2n, where n is the mean of the log2-transformed expression measures within each group) (± SD) are represented on this figure, relative to the geometric mean of the appropriate control group.

Expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, Atoh8, and Hamp1 in the livers of mice with genetic iron overload. Mice with liver-specific knockout of Smad4 (A) or Hamp1 disruption (B) were compared with their respective controls. Expression levels were normalized to HPRT and log2 transformed for the statistical analyses. Statistically significant differences relative to the controls were determined by Student t tests. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Geometric means (2n, where n is the mean of the log2-transformed expression measures within each group) (± SD) are represented on this figure, relative to the geometric mean of the appropriate control group.

Hamp1 knockout mice have increased Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 gene expression

Targeted disruption of the hepcidin1 gene also results in early and severe multivisceral iron overload.15 To check whether the Bmp signaling pathway is still functional in these mice, we assessed the expression of the same genes in the liver of 5 Hamp1 knockout mice and controls of comparable genetic background at 10 weeks of age. As shown in Figure 4B, the Hamp1−/− mice behave like mice fed an iron-enriched diet. Iron overload induced by Hamp1 deficiency is indeed able to increase the expression not only of Bmp6 but also of Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8.

Discussion

Analysis of liver transcription profiles in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice fed an iron-deficient or an iron-enriched diet allowed us to identify 4 genes that were regulated by iron similarly to hepcidin in both strains. These results were confirmed by quantitative real-time PCR and point out important molecules participating in the BMP/Smad signaling pathway that regulates hepcidin expression in vivo.

We therefore tested whether the dietary iron content effectively activated/repressed the Smad signaling pathway in these mice through phosphorylation of the receptor-regulated Smads. Activation of Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 indeed is considered to be the major signaling pathway for BMPs.31 Interestingly, we observed that Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation was induced by iron overload, and that this induction was proportional to the liver iron burden of the mice. Conversely, it was reduced by iron deficiency. This is the first demonstration that dietary iron regulates hepcidin synthesis in vivo through Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation. Of note, injection of iron dextran was also shown to lead to an increase in Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in liver extracts from both zebrafish and mouse.32

Which of the BMP ligands is (are) responsible for the observed activation of the Smad pathway by iron in vivo is still unknown. Recent studies have shown that many ligands of the TGF-β/BMP superfamily could positively regulate hepcidin expression in vitro9,12,13 and in vivo.10 However, in these studies, hepatic cells or mice were exposed to high levels of exogenous ligands and the observed signals may not reflect the physiological response to iron exposure. Our data suggest that Bmp6, which is highly expressed in the liver,33 has a preponderant role in the activation of the Smad signaling pathway in vivo. We indeed showed in the present study that liver expression of Bmp6 was transcriptionally regulated by iron (ie, induced by iron overload and repressed by iron deficiency) and that its induction paralleled the liver iron burden of the mice. Of note, expression of Bmp2 was also slightly increased in mice with the most severe iron burden (ie, the B6 mice fed the iron-enriched diet) which indicates that, in addition to Bmp6, Bmp2 can also participate in the activation of the Smad signaling pathway. No other ligand of the TGF-β/BMP superfamily, including Bmp4, had its gene expression significantly modulated by iron in vivo. What exactly triggers Bmp6 and Bmp2 modulation by the dietary iron content remains to be determined, but may well be serum transferrin saturation.34,35

The composition of BMP ligands after exogenous challenges has been observed to be modulated both at the mRNA and at the protein levels.36 It is therefore likely that Bmp6 and Bmp2 protein levels in iron-overloaded and in iron-deficient mice reflect Bmp6 and Bmp2 transcript levels. Whereas hemojuvelin (HJV) acts as a BMP coreceptor to enhance cellular responses to BMP ligands and increase hepcidin expression,9 soluble HJV seems to bind and sequester BMP ligands and thus to inhibit BMP signaling and hepcidin expression both in vitro and in vivo.10 Interestingly, the ability of soluble HJV to inhibit BMP induction of hepcidin promoter activation in Hep3B cells is selective and much more effective for BMP6 than for other ligands.10 siRNA inhibition of endogenous BMP6 in HepG2 cells significantly reduces basal hepcidin expression,10 confirming that regulation of hepcidin by BMP6 is bidirectional, that is, not only induced when BMP6 is added to cells, but also repressed when endogenous BMP6 expression is decreased. Altogether, these results converge to suggest that BMP6 is the ligand of the TGF-β/BMP superfamily that has a key role in the maintenance of systemic iron homeostasis, although BMP2 can also function as an endogenous regulator of hepcidin expression in vivo, especially when body iron stores are abundant and require strong activation of the Smad signaling pathway.

Our data also show that Id1, Smad7, and Atoh8 gene expression in the liver of mice fed an iron-enriched or an iron-deficient diet follows Bmp6 gene expression and the level of Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation. Id1 is known to be a direct target gene for BMPs that strongly activate its promoter in a Smad-dependent manner. Indeed, Smad-binding elements (SBEs) and a GC-rich region, which bind both Smad1 and Smad5, confer BMP responsiveness to the Id1 promoter.27 Receptor-activated Smads have also been shown to regulate Smad7 transcription through direct binding to SBEs on its promoter.37 However, no information on the regulation of Atoh8 transcription is yet available. To check that the regulation of these genes by body iron stores relies on the formation of heteromeric complexes between phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 and Smad4 and the translocation of these complexes into the nucleus, we measured their expression in mice with liver-specific knockout of Smad4. These mice have compromised Bmp signaling and develop severe iron overload.12 Interestingly, Bmp6 gene expression is increased in these mice, which shows that its up-regulation by iron is not restricted to dietary iron overload. However, the expression of Id1, Smad7, and Atoh8 is decreased, suggesting that Atoh8, like Id1 and Smad7, is a direct target gene for BMP ligands. Further analyses are conducted to check whether receptor-activated Smads also bind to the Atoh8 promoter. Of note, in mice with genetic iron overload due to targeted disruption of Hamp1,15 Bmp signaling is functional, and the expression of Bmp6, Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 is increased as it is in mice with dietary iron overload.

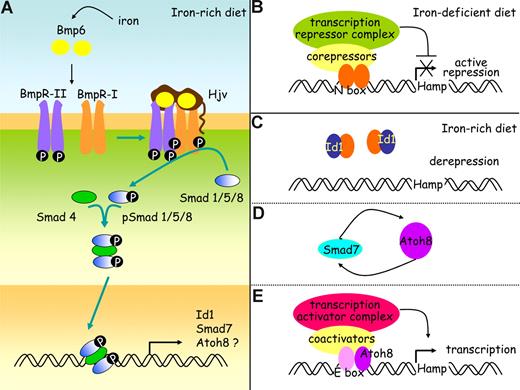

It is not clear yet how Id1, Smad7, and Atoh8, whose expression is regulated by body iron providing that Smad4 is functional, can act on hepcidin regulation. Inhibitor of differentiation proteins Id1 associate with tissue-specific basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors that can either activate38 or repress transcription.39 In this study, we observed that activation of the BMP/Smad signaling pathway by iron leads to synthesis of Id1 that seems proportional to the needs for hepcidin. It should therefore be explored whether Id1 could overcome the inhibitory effect of a transcription factor and allow hepcidin transcription to proceed. The expression of Smad7 mRNA is known to be quickly induced by members of the TGF-β family.40 Smad7 interferes with binding to type I receptors and thus activation of receptor-regulated Smads or recruits the E3 ubiquitin ligase Smurf to receptors and thus targets them for degradation.26,41 Although Smad7 could participate in a negative feedback loop to control the intensity and duration of responses to ligands such as Bmp6,26,41 it could also enhance transcriptional activity of Atoh8, a bHLH protein28 whose role in the maintenance of iron balance was unsuspected so far, as was shown recently for another bHLH protein, MyoD.42 The hepcidin promoter contains several E-boxes43 known to interact with bHLH transcription factors and it would be interesting to test whether Atoh8 could activate the hepcidin promoter. This would establish a link among iron, the different proteins identified in this study, and hepcidin, as depicted in our working model (Figure 5).

A working model for hepcidin regulation by iron in the mouse. (A) Bmp6, whose expression is induced by iron, binds to type I and II receptors and to the coreceptor, hemojuvelin (Hjv). The constitutively active kinase domains of type II receptors phosphorylate type I receptors, and this in turn activates the Smad signaling pathway through phosphorylation of receptor Smads (Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8). These associate with co-Smads (Smad4) to form a heteromeric complex that translocates to the nucleus and stimulates the expression of a wide range of target genes, including the genes coding for Id1, Smad7, and possibly also Atoh8. Hypothetical roles for Id1, Smad7, and Atoh8 are presented on panels B through E. (B) When dietary iron availability is low, hepcidin transcription is repressed by specific basic-loop-helix (bHLH) repressors. (C) When the diet iron content increases, inhibitor of differentiation proteins Id1 are synthesized. These are known to associate with bHLH proteins and prevent them from binding DNA. By sequestering the bHLH repressors, Id1 proteins may stop them from achieving their inhibiting functions on the hepcidin promoter. (D) Iron overload also increases Smad 7, which could enhance Atoh8 activity as it does for another bHLH transcription activator, MyoD. (E) The hepcidin promoter contains several E-boxes known to interact with bHLH transcription factors and further investigation will determine whether Atoh8 binds to and activates the hepcidin promoter.

A working model for hepcidin regulation by iron in the mouse. (A) Bmp6, whose expression is induced by iron, binds to type I and II receptors and to the coreceptor, hemojuvelin (Hjv). The constitutively active kinase domains of type II receptors phosphorylate type I receptors, and this in turn activates the Smad signaling pathway through phosphorylation of receptor Smads (Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8). These associate with co-Smads (Smad4) to form a heteromeric complex that translocates to the nucleus and stimulates the expression of a wide range of target genes, including the genes coding for Id1, Smad7, and possibly also Atoh8. Hypothetical roles for Id1, Smad7, and Atoh8 are presented on panels B through E. (B) When dietary iron availability is low, hepcidin transcription is repressed by specific basic-loop-helix (bHLH) repressors. (C) When the diet iron content increases, inhibitor of differentiation proteins Id1 are synthesized. These are known to associate with bHLH proteins and prevent them from binding DNA. By sequestering the bHLH repressors, Id1 proteins may stop them from achieving their inhibiting functions on the hepcidin promoter. (D) Iron overload also increases Smad 7, which could enhance Atoh8 activity as it does for another bHLH transcription activator, MyoD. (E) The hepcidin promoter contains several E-boxes known to interact with bHLH transcription factors and further investigation will determine whether Atoh8 binds to and activates the hepcidin promoter.

In summary, our data underscore a critical role of Bmp6 in the maintenance of systemic iron homeostasis in 2 different strains of mice and suggest that Smad7, Id1, and Atoh8 may participate in this maintenance. They also underline that Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation in the liver is controlled by body iron. It is now important to understand how exactly these molecules are involved in the complex process of regulation of hepcidin synthesis by iron.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the “Service de Zootechnie” (Institut Fédératif de Recherche 30) and the platform “Génomique” (Génopole Toulouse) for assistance and skilled advice.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, Paris, France (ANR, program IRONGENES), the European Commission, Brussels, Belgium (LSHM-CT-2006–037296: EUROIRON1), and the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC), Villejuif, France.

Authorship

Contribution: L.K. and D.M. performed research, analyzed data, and reviewed the paper; A.M. and J.M. performed research and reviewed the paper; V.D. and R.B. performed research; R.-H.W. and C.D. contributed Smad-deficient mice and reviewed the paper; S.V. contributed Hamp1-deficient mice, discussed the experiments, and reviewed the paper; H.C. and M.-P.R. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, performed statistical analysis, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marie-Paule Roth, Inserm U563, CHU Purpan, BP 3028, F-31024 Toulouse Cedex 3, France; e-mail: marie-paule.roth@inserm.fr.

References

Author notes

L.K. and D.M. contributed equally to this work

H.C. and M.-P.R. contributed equally to this work