Abstract

We have recently described a new form of light chain deposition disease (LCDD) presenting as a severe cystic lung disorder requiring lung transplantation. There was no bone marrow plasma cell proliferation. Because of the absence of disease recurrence after bilateral lung transplantation and of serum-free light chain ratio normalization after the procedure, we hypothesized that monoclonal light chain synthesis occurred within the lung. The aim of this study was to look for the monoclonal B-cell component in 3 patients with cystic lung LCDD. Histologic examination of the explanted lungs showed diffuse nonamyloid κ light chain deposits associated with a mild lymphoid infiltrate composed of aggregates of small CD20+, CD5−, CD10− B lymphocytes reminiscent of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue. Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we identified a dominant B-cell clone in the lung in the 3 studied patients. The clonal expansion of each patient shared an unmutated antigen receptor variable region sequence characterized by the use of IGHV4-34 and IGKV1 subgroups with heavy and light chain CDR3 sequences of more than 80% amino acid identity, a feature evocative of an antigen-driven process. Combined with clinical and biologic data, our results strongly argue for a new antigen-driven primary pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorder.

Introduction

Monoclonal immunoglobulin (IG) synthesis characterizes monoclonal gammopathies that result from a clonal proliferation of B lymphocytes. The monoclonal component may be directly pathogenic, particularly through its high serum concentration, its abnormal structure, or its antibody activity, leading to several manifestations or affections including tissular deposits most often composed of immunoglobulin light chain subunits. Light chain deposition is responsible for light-chain amyloidosis and light chain deposition disease (LCDD), the term LCDD being restricted to the nonamyloid form of these deposits. LCDD, described by Randall in 1976,1 is a systemic multivisceral disorder with a constant renal involvement.2-7 Apart from the kidneys, the heart and liver are the most frequently concerned organs.2-7 Lung involvement is asymptomatic and usually diagnosed at the time of autopsy by systematic immunofluorescence (IF) study. In 1987, nonamyloid nodular light chain deposits restricted to the lung were described and recognized as an new LCDD clinicopathologic entity.8-13 The nodules were usually an incidental radiologic finding. They may be single or multiple and ranged in size from 0.7 to 4 cm. In 2006, we reported in 3 patients a new clinicopathologic presentation named cystic lung LCDD.14 The patients had dyspnea and numerous cysts distributed in both lungs on the computed tomography (CT) scan. Unlike systemic LCDD, the patients progressively developed end-stage respiratory failure requiring lung transplantation. Lung transplantation was bilateral in all cases. Moreover, none of the patients had renal disturbances, and the origin of light chain production was not found by bone marrow biopsy and aspiration. Histologic examination of the lung explant specimens showed diffuse parenchymal nonamyloid monoclonal κ light chain deposits associated with numerous cysts and a mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. Despite the lack of morphologic criteria for a pulmonary B-cell neoplasm, the normalization of serum-free light chain κ/λ ratio after bilateral lung transplantation and the absence of recurrence of the disease several years after the procedure led us to speculate that B-cell clonal expansion was localized within the lung. Therefore, we design the present study to look for the monoclonal B-cell component.

Using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), we identified a dominant B-cell clone in the lung of the 3 studied patients without peripheral blood involvement. Furthermore, we showed that each patient's specific clonal expansion shared an unmutated IGHV4-34/IGKV1 receptor. Combined with clinical and biologic observations, our data strongly suggest that cystic lung LCDD is a new antigen-driven primary pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorder.

Methods

Patients

Among the 572 patients who underwent lung transplantation at Beaujon (Clichy, France) and Foch (Suresnes, France) Hospitals, 36 had a pulmonary cystic disorder. Of them, 3 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of cystic lung LCDD.14 The diagnosis of LCDD was made before lung transplantation in only one patient (patient 2) on a surgical lung biopsy. For the 2 other patients, the diagnosis was established on the explanted lungs.

Diagnosis of LCDD.

Histologic examination of lung specimens showed similar lesions that has been previously described.14 Briefly, the main finding was the presence of nonmyeloid amorphous eosinophilic deposits composed of monotypic κ light chains widely infiltrating alveolar walls, small airways, and vessels. Congo red did not show apple-green birefringence under polarized light, and electron microscopy revealed granular electron-dense deposits, thus excluding amyloidosis. The κ light chain nature of the deposits was determined by immunofluorescence study on frozen tissue sections. λ, IgG, IgA, and IgM were not detected. The deposits were surrounded by macrophagic giant cells and were associated with cystic lung destruction characterized by emphysematous-like changes and marked bronchiolar dilatation. Only small preserved lung areas were found. A mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate was present in the lung parenchyma and is further characterized in the present study.

Clinical presentation.

Clinical characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1. Two of them (patients 1 and 2) have already been reported.14 Briefly, the patients presented with a progressive obstructive dyspnea and numerous cysts diffusely distributed in both lungs on the CT scan. In one of them, small bilateral hilar lymphadenopathies appeared during the follow-up (patient 1). End-stage respiratory failure reached over a period from 3 to 10 years required lung transplantation, which was bilateral in all cases. Before lung transplantation, one patient (patient 2) underwent high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous blood stem cell transplantation as proposed in severe systemic LCDD. However the disease persisted with worsening of dyspnea and dramatic increase in the number of cysts.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| At the onset of symptoms | 33 | 28 | 37 |

| At the time of LT | 36 | 39 | 42 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female |

| Smoking status (pack-years) | Former smoker (1) | Nonsmoker | Former smoker (8) |

| Environment or occupational exposure | Not found | Not found | Not found |

| Adenopathies | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Splenomegaly | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Hepatomegaly | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Viral status, serology | |||

| HCV infection | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| HIV infection | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Monoclonal IG before LT* | |||

| Serum | Free κ light chain | (−) | (−) |

| Urine | (−) | ND | ND |

| Serum IgG, IgA, IgM levels | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Bone marrow plasmocytes, % | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 |

| Renal function (serum creatinine level, μmol/L) | Normal (50) | Normal (55) | Normal (100) |

| Proteinuria, mg/d | 70 | 60 | 200 |

| Liver function tests | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Heart function† | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Extrapulmonary deposits | |||

| Bone marrow | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Salivary glands | + | (−) | + |

| Skin | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Duodenum | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Rectum | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Kidney | ¤ | ¤ | (−) |

| Autologous blood stem cell transplantation before LT | No | Yes‡ | No |

| Follow up, mo | 39 | 69 | 33 |

| Monoclonal IG after LT* | |||

| Serum | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Urine | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Recurrence of the disease | No | No | No |

| . | Patient 1 . | Patient 2 . | Patient 3 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| At the onset of symptoms | 33 | 28 | 37 |

| At the time of LT | 36 | 39 | 42 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female |

| Smoking status (pack-years) | Former smoker (1) | Nonsmoker | Former smoker (8) |

| Environment or occupational exposure | Not found | Not found | Not found |

| Adenopathies | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Splenomegaly | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Hepatomegaly | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Viral status, serology | |||

| HCV infection | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| HIV infection | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Monoclonal IG before LT* | |||

| Serum | Free κ light chain | (−) | (−) |

| Urine | (−) | ND | ND |

| Serum IgG, IgA, IgM levels | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Bone marrow plasmocytes, % | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 |

| Renal function (serum creatinine level, μmol/L) | Normal (50) | Normal (55) | Normal (100) |

| Proteinuria, mg/d | 70 | 60 | 200 |

| Liver function tests | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Heart function† | Normal | Normal | Normal |

| Extrapulmonary deposits | |||

| Bone marrow | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Salivary glands | + | (−) | + |

| Skin | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Duodenum | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Rectum | ¤ | (−) | ¤ |

| Kidney | ¤ | ¤ | (−) |

| Autologous blood stem cell transplantation before LT | No | Yes‡ | No |

| Follow up, mo | 39 | 69 | 33 |

| Monoclonal IG after LT* | |||

| Serum | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Urine | (−) | (−) | (−) |

| Recurrence of the disease | No | No | No |

LT indicates lung transplantation; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; (−), absent; ND; not done; +, present; and ¤, no biopsy performed.

Protein electrophoresis and immunofixation.

Evaluated by echocardiography and right cardiac catheterization.

Without improvement or stabilization.

Hematologic characteristics.

In the serum, only a free monoclonal κ light chain was detected in one patient (patient 1; Table 1). Bone marrow biopsy and bone marrow aspiration did not show increase in the number of plasma cells or lymphocytes. Moreover, plasma cells did not show cytologic abnormalities, and the κ/λ ratio was preserved.

Systemic extension of the disease.

Investigations for systemic extension of the disease especially including renal, liver, and heart investigations, revealed only monotypic κ light chain deposits in the salivary glands of patients 2 and 3 (Table 1).

Outcome.

The free κ light chain present before lung transplantation in patient 1 was undetectable 3 months after the procedure. The 3 patients are still alive without recurrence of the disease 47 months (range: 33 to 69 months) after lung transplantation.

Histologic and immunohistochemical evaluation of the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

Explanted lung tissue was taken from the upper, middle, and lower lobes. Hilar and lobar lymph nodes were also sampled at time of transplantation. At least 20 paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were available for each case as well as 3 lung frozen samples. Immunophenotyping of the lymphoid population was performed on paraffin-embedded contiguous sections on Ventana Benchmark automated immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) with commercial primary antibodies directed against CD20 (clone L26, 1/500; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), CD5 (clone 4C7, 1/40; Novocastra, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom), CD10 (clone 56C6, 1/10; Novocastra), CD138 (clone MI15, 1/200; Dako), Bcl2 (clone 124, 1/10; Dako), IgD (polyclonal A0093, 1/50; Dako), CD23 (clone 1B12, 1/40; Novocastra), and Ki-67 (clone MIB-1, 1/150; Dako). IF on deparaffined sections was performed to identify κ or λ light chains (polyclonal, 1/50; Dako) within the cytoplasm of plasma cells.

DNA extraction and clonality analysis

DNA was obtained by a standard proteinase K digestion and a phenol-chloroform extraction of lung explant specimens, regional lymph nodes, and post–lung transplantation peripheral blood samples after isolation of mononuclear cells on Ficoll gradient. When extracted from tissue samples, DNA was submitted to a quality control: DNA was amplified using a multiplex PCR generating 100, 200, 300, 400, and 600 base pair PCR fragments as reported.15 The DNA quality was scored as good when 4 or 5 bands were obtained, correct when 3 bands were obtained, and insufficient for full clonality analysis when fewer than 3 bands were obtained. For immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement study, the 2 PCR FR1 and FR2 were performed according to BIOMED-2 protocol.16 The third PCR, FR3, was done as previously described.17 Because of the expected size range of FR1-JH (310-360 base pairs), FR2-JH (250-295 base pairs), and FR3-JH (75-140 base pairs) PCR products, the interpretation of PCR results was, as expected, directly related to the maximum size amplified by the sample in the control gene PCR. For heavy chain CDR3 length diversity analysis, the amplified products were run on an ABI prism 3100 genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Results were analyzed using Genscan analysis software (Applied Biosystems). Samples with a unique dominant peak within the polyclonal background were considered as clonal and the clonal population was characterized by its heavy chain CDR3 size. The B-cell repertoire pattern in pulmonary tissue sample was compared with that in blood sample and in hilar lymph node tissue sample when available. In a patient, 2 dominant B-cell populations were considered identical when they displayed the same heavy chain CDR3 size. For κ light chain gene rearrangement analysis, BIOMED-2 protocol was used, and PCR products were electrophoresed in an 8% polyacrylamide gel after heteroduplex formation.15

Approval for this study was obtained from the CRETEIL hospital Institutional Review Board (Comité de protection des personnes). It confirmed that, as recommended by the French governmental Agence Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Evaluation en Santé (ANAES) in its “Recommendations for cryopreserved cell and tissue libraries for molecular analyses,” patients were informed that part of the specimens could be used for molecular analysis provided that all routine examinations have been performed (http://www.anaes.fr/ANAES/SiteWeb.nsf/wRubriquesID/APEH-3ZMHJP) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sequence analysis

For nucleotide sequence analysis, PCR products were directly sequenced (for heavy chain genes sequencing) or strong dominant PCR products were extracted from 6% polyacrylamide gel by elution (for light chain genes sequencing). Big Dye Terminator cycle sequencing reaction kit (Applied Biosystems) was used before electrophoresis on an automated sequencer (ABI PRISM 3130XL; Applied Biosystems). The sequences were aligned to immunoglobulin sequences using IMGT/V-QUEST18 and IMGT/JunctionAnalysis,19 from IMGT (Centre Informatique National de l'Enseignement Supérieur, Montpellier, France), the international ImMunoGeneTics information system (http://imgt.cines.fr20 ; founder and director Marie-Paule Lefranc, Montpellier, France21 ). IGHV/IGHD/IGHJ or IGKV/IGKJ usage was determined and the heavy or light CDR3 was identified. Somatic mutations were defined as nucleotide substitutions after elimination of the known polymorphisms described in IMGT. The ability to code for functional chains was determined by translating DNA sequences into amino acids. European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL)22 accession numbers are as follows: AM980824: partial IGHV gene for immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region, patient 1; AM980825: partial IGHV gene for immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region, patient 2; and AM980826: partial IGHV gene for immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region, patient 3.

FISH studies

Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses were performed on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections from lung tissue specimens using split-signal DNA probes for MALT1 (Dako) according to the manufacturer's recommendations (http://www.euro-fish.org).

Results

Nonamyloid monotypic κ light chain deposits are associated with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate

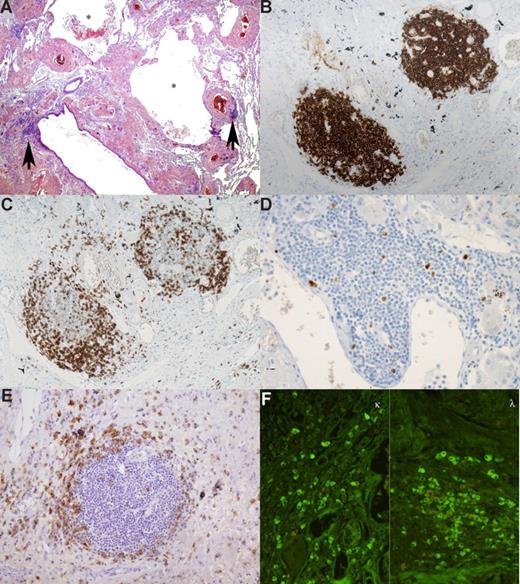

The density of the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate was variable among the 3 patients but remained mild and nondestructive in all cases. Very scarce lymphoid aggregates were present along the bronchovascular bundles in patients 2 and 3, whereas lymphoid aggregates were more numerous in patient 1 (Figure 1A). Rare lymphoid aggregates displayed features reminiscent of lymphoid follicles with atrophic germinal centers. Cytologically, the lymphoid cells were small, with scanty cytoplasm, round nuclei, and mild plasmacytoid differentiation. There was no large cell component. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that the lymphoid cells displayed a CD20+, CD5−, CD10−, Bcl2+, CD23−, IgD− phenotype (Figure 1B) and were associated with numerous reactive CD5+ T cells (Figure 1C). These lymphoid cells did not react with κ and λ light chains antibodies. Rare lymphoid follicles were associated with a CD23+ follicular dendritic cell meshwork. Less than 5% of these lymphocytes were labeled by anti–Ki-67 antibody (Figure 1D). In addition, scattered mature plasma cells expressing CD138 were observed around the lymphoid aggregates (Figure 1E), or at distance admixed with light chain deposition. Immunofluorescence analysis with κ and λ light chain antibodies of this plasma cell component did not show any light chain restriction (Figure 1F).

Pulmonary lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. This low-power view shows abundant eosinophilic amorphous extracellular pulmonary deposits associated with several cysts (*). Three lymphoid nodules are seen, and 2 of them ( ) are located in the vicinity of bronchioles (A). Immunohistochemical study revealed that the nodules are composed mainly of small CD20+ lymphocytes (B). At the periphery, small CD5+ cells were present (C). Less than 5% of lymphocytes were labeled by anti–Ki-67 antibody (D). Anti-CD138 antibody highlights the presence of plasma cells around the nodules (E). IF performed on deparaffined sections demonstrated that plasma cells did not show light chain restriction (F). All slides were examined on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an epifluorescent illuminator (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Original magnification 20×/0.075 objective.

) are located in the vicinity of bronchioles (A). Immunohistochemical study revealed that the nodules are composed mainly of small CD20+ lymphocytes (B). At the periphery, small CD5+ cells were present (C). Less than 5% of lymphocytes were labeled by anti–Ki-67 antibody (D). Anti-CD138 antibody highlights the presence of plasma cells around the nodules (E). IF performed on deparaffined sections demonstrated that plasma cells did not show light chain restriction (F). All slides were examined on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an epifluorescent illuminator (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Original magnification 20×/0.075 objective.

Pulmonary lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. This low-power view shows abundant eosinophilic amorphous extracellular pulmonary deposits associated with several cysts (*). Three lymphoid nodules are seen, and 2 of them ( ) are located in the vicinity of bronchioles (A). Immunohistochemical study revealed that the nodules are composed mainly of small CD20+ lymphocytes (B). At the periphery, small CD5+ cells were present (C). Less than 5% of lymphocytes were labeled by anti–Ki-67 antibody (D). Anti-CD138 antibody highlights the presence of plasma cells around the nodules (E). IF performed on deparaffined sections demonstrated that plasma cells did not show light chain restriction (F). All slides were examined on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an epifluorescent illuminator (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Original magnification 20×/0.075 objective.

) are located in the vicinity of bronchioles (A). Immunohistochemical study revealed that the nodules are composed mainly of small CD20+ lymphocytes (B). At the periphery, small CD5+ cells were present (C). Less than 5% of lymphocytes were labeled by anti–Ki-67 antibody (D). Anti-CD138 antibody highlights the presence of plasma cells around the nodules (E). IF performed on deparaffined sections demonstrated that plasma cells did not show light chain restriction (F). All slides were examined on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope equipped with an epifluorescent illuminator (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Original magnification 20×/0.075 objective.

The hilar and lobar lymph node architecture was preserved. The cortex and medulla were infiltrated by some κ light chain deposits and a mild plasma cell infiltrate without cytologic abnormalities. κ and λ light chains were equally expressed by the plasma cells.

Examination of the salivary glands containing κ light chain deposits (patients 2 and 3) disclosed only a minimal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with similar morphologic and immunophenotypical features as observed in the lung. There were occasional plasma cells that did not show light chain restriction.

Finally, the pulmonary, nodal, and salivary gland infiltrate did not exhibit the characteristic morphologic criteria of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, that is, hyperplastic reactive lymphoid follicles, expansion of the marginal zone by centrocyte-like tumor cells, and lymphoepithelial lesions. The pulmonary lymphoid infiltrate was reminiscent of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT).23

All 3 patients present a lung monoclonal B-cell population

DNAs extracted from biopsies were analyzed for their amplificability. Indeed, poor DNA quality could lead to false-positive results due to misinterpretation of pseudoclonality.15 All DNA has excellent or correct quality control in agreement with data currently observed from frozen or formalin-fixed samples.15

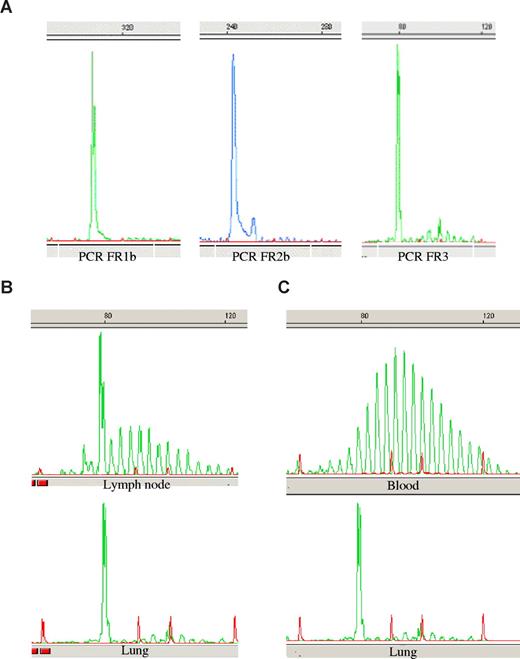

A dominant B-cell clone was identified in the lung tissue of the 3 patients. According to the DNA quality, the dominant clone was detected with FR1, FR2, and FR3 PCR (patients 1 and 3; Figure 2A) or by one PCR (FR2) for patient 2. As shown in Figure 2, this B-cell clone was largely predominant compared with the surrounding normal B cells. For patients 1 and 3, hilar lymph nodes could be analyzed. In each case, a faint dominant B-cell clone was found. It was identical to the pulmonary dominant clone (Figure 2B).

Genscan analysis of PCR products. Amplifications of immunoglobulin heavy chain CDR3 sequences were performed using the 3 FR1, FR2, and FR3 primer sets. PCR products were run on a sequence analyzer and sizes were determined using a size marker (in red) and the Genscan software. The figure shows representative data in patient 1 of (A) the dominant clone detected in the lung, (B) the PCR product alignment of lung and lymph node dominant clone, and (C) the comparison of lung clone and polyclonal blood B-cell repertoire.

Genscan analysis of PCR products. Amplifications of immunoglobulin heavy chain CDR3 sequences were performed using the 3 FR1, FR2, and FR3 primer sets. PCR products were run on a sequence analyzer and sizes were determined using a size marker (in red) and the Genscan software. The figure shows representative data in patient 1 of (A) the dominant clone detected in the lung, (B) the PCR product alignment of lung and lymph node dominant clone, and (C) the comparison of lung clone and polyclonal blood B-cell repertoire.

Post–lung transplantation peripheral blood B-cell repertoire was polyclonal in patients 2 and 3 (Figure 2C). Because neither lung transplantation nor immunosuppressive associated therapy is supposed to cure a leukemic form of small B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, we conclude that lung clonal B-cell detection was not related to contaminant circulating tumoral cells. In patient 1, peripheral blood B-cell repertoire analysis was not conclusive because of deep B-lymphocyte depletion.

All 3 clonal populations carry an unmutated IGHV4-34/IGKV1 stereotyped receptor

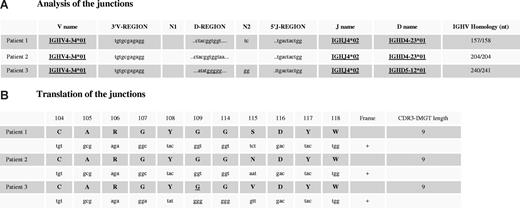

To further characterize these clonal populations, we decided to sequence the IGH clonal rearrangement to look for somatic mutations, an indirect criteria for antigen-driven B-cell expansion.24 As expected from Genscan analysis, a clear dominant sequence was obtained by direct sequencing of PCR products (data not shown). Patients shared a common IGHV4-34*01 and IGHJ4*02 gene usage. IGHD4-23*01 gene was also common to patients 1 and 2 (Figure 3A). Interestingly, no deletion of the 3′V-region or N1 region was observed in the 3 patients. The N2 region was restricted to 2 nucleotides (patients 1 and 3) and was absent in patient 2. However, although the N diversity was restricted, it clearly differed between patients, avoiding PCR contamination. Surprisingly, all 3 IGVH genes were found unmutated.

Alignment of nucleotide sequences and translation of IG heavy chain CDR3. DNA extracted from lung explant specimens was amplified using the FR1/JH BIOMED-2 PCR protocol. After purification, PCR fragments were directly sequenced. (A) Sequences were aligned to immunoglobulin sequences using IMGT/V-QUEST18 and IMGT/JunctionAnalysis,19 from IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics information system (http://imgt.cines.fr). Somatic mutations were defined as nucleotide substitutions after elimination of the known polymorphisms described in the IMGT database.20 (B) The same database determines the ability of sequences to code for functional heavy chains. First line includes amino acid positions according to the IMGT unique numbering for V-DOMAIN.21

Alignment of nucleotide sequences and translation of IG heavy chain CDR3. DNA extracted from lung explant specimens was amplified using the FR1/JH BIOMED-2 PCR protocol. After purification, PCR fragments were directly sequenced. (A) Sequences were aligned to immunoglobulin sequences using IMGT/V-QUEST18 and IMGT/JunctionAnalysis,19 from IMGT, the international ImMunoGeneTics information system (http://imgt.cines.fr). Somatic mutations were defined as nucleotide substitutions after elimination of the known polymorphisms described in the IMGT database.20 (B) The same database determines the ability of sequences to code for functional heavy chains. First line includes amino acid positions according to the IMGT unique numbering for V-DOMAIN.21

Nucleotide sequence translation revealed not only an uncommon short 9 amino acid heavy chain CDR3 length but also an only one amino acid divergence between patients (Figure 3B). It is interesting to note in patient 3, the usage of a different IGHD gene (IGHD5-12*01; instead of IGHD4-23*01 in the other 2 patients), which, however, encodes the same amino acid motif YGG as a results of 2 mutations. The CDR3 comprises 2 charged amino acids, the basic arginine (R106) (from the 3′V-REGION) and the acidic aspartic acid (D116) (from the 5′J-REGION). The tip of the CDR3 loop that corresponds to the D-REGION is occupied by a tyrosine, 2 glycine, and the amino acid 115 that results from the D-J rearrangement and is the only amino acid that differs (P1: serine, small and neutral; P2: asparagine, small and hydrophilic; and valine: medium size and hydrophobic). Those CDR3 sequences were compared with the 7.268 in-frame IGH VDJ sequences of the IMGT/LIGM-DB database20 and with our 10 previously published clonal pulmonary MALT lymphoma IGH VDJ sequences,17 which have been further extended by Bende et al.25 No similar junctions either for length or for motive were found.

To further look for a closely homologous (“stereotyped”) receptor, as described in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),26,27 we analyzed κ light chain gene rearrangements. Sequence analysis in patients 2 and 3 showed quite similar amino acid CDR3 sequences CQQYNSYPLTF and CQQYYSYPQTF, respectively (differences indicated in bold). The 3′V-REGION of the IGKV allows for the identification of the sequence CQQYNSYP as being from IGKV1-16 and the sequence CQQYYSYP as being from IGKV1-8. IGKV1-16 is rearranged to IGKJ4. It is not possible due to the mutation at the V-J junction to identify the IGKJ rearranged to IGKV1-8 (IMGT Protein display, http://imgt.cines.fr20 ); light chain CDR3 sequences were of the same length. Unfortunately, we did not have enough DNA to perform sequence analysis of the rearranged κ light chain genes in patient 1.

The pulmonary lymphoid infiltrate did not show rearrangement of the MALT1 gene

Using FISH analysis, we did not find any rearrangement of the MALT1 gene, a chromosomal alteration commonly observed in pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.28

Discussion

Pulmonary nonamyloid light chain deposits occur in the 3 following forms of LCDD: the systemic multivisceral form, the pulmonary nodular form, and, as we recently suggested, the pulmonary cystic form. The current study demonstrates that cystic lung LCDD clearly differs from the 2 other forms by clinical and molecular features (Table 2).

Main characteristics that distinguish the 3 forms of LCDD involving the lung

| . | Cystic lung LCDD, n = 414 * . | Systemic multivisceral LCDD n = 912-7 . | Nodular lung LCDD n = 108-13 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (range) | 29.5 (20-37) | 55 (33-80) | 58 (33-76) |

| Sex ratio, M/F | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/3 |

| Organ involvement | |||

| Lung | Yes (dyspnea) | Yes (asymptomatic) | Yes (asymptomatic) |

| Kidney | No | Yes (proteinuria, renal failure) | No |

| Heart | No | Yes (arrhythmias, heart failure) | No |

| Cause of death | Respiratory failure | Renal or heart failure | No death |

| Recurrence after adequate organ transplantation | No† | Yes† | Not needed |

| Monoclonal component (serum/urine) | 25% (serum free κ light chain) | 85%29 | ND |

| Primary bone marrow plasma cell proliferation | No | Yes (75%)‡ | No |

| Primary pulmonary lymphoproliferation | Yes | No | Yes (50%) |

| Characterization of monoclonal component | |||

| Clonal V heavy chain | IGHV4-34 | Not determined | Not determined |

| Clonal V light chain | κ, IGKV1 | κ, IGKV430 | κ, IGKV411 |

| Somatic mutations | No | Yes31,32 | Not determined |

| . | Cystic lung LCDD, n = 414 * . | Systemic multivisceral LCDD n = 912-7 . | Nodular lung LCDD n = 108-13 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (range) | 29.5 (20-37) | 55 (33-80) | 58 (33-76) |

| Sex ratio, M/F | 1/3 | 2/1 | 2/3 |

| Organ involvement | |||

| Lung | Yes (dyspnea) | Yes (asymptomatic) | Yes (asymptomatic) |

| Kidney | No | Yes (proteinuria, renal failure) | No |

| Heart | No | Yes (arrhythmias, heart failure) | No |

| Cause of death | Respiratory failure | Renal or heart failure | No death |

| Recurrence after adequate organ transplantation | No† | Yes† | Not needed |

| Monoclonal component (serum/urine) | 25% (serum free κ light chain) | 85%29 | ND |

| Primary bone marrow plasma cell proliferation | No | Yes (75%)‡ | No |

| Primary pulmonary lymphoproliferation | Yes | No | Yes (50%) |

| Characterization of monoclonal component | |||

| Clonal V heavy chain | IGHV4-34 | Not determined | Not determined |

| Clonal V light chain | κ, IGKV1 | κ, IGKV430 | κ, IGKV411 |

| Somatic mutations | No | Yes31,32 | Not determined |

ND indicates not done.

And the present study.

Bilateral lung transplantation.

Renal transplantation.

Cystic lung LCDD is a rare disorder,14 mostly arising in young females. They had dyspnea associated with an obstructive pattern and numerous cysts distributed in both lung fields on the CT scan. The number of cysts progressively increased with a concomitant worsening of dyspnea that required lung transplantation after a few years. Thirty-three to 69 months after bilateral lung transplantation, the patients are in good condition without recurrence of the disease. These clinical findings show that lung involvement in cystic lung LCDD threatens a patient's life as opposed to what is observed in systemic LCDD and nodular lung LCDD. Moreover, patients affected by cystic lung LCDD are 25 years younger than the others.2-13 Besides the age of patients and pulmonary manifestations, cystic lung LCDD may be clinically distinguished from the systemic multivisceral form by the absence of renal involvement and of relapse after adequate organ transplantation.33

In the systemic form of LCDD, monoclonal light chains deposited in the target organs are produced by a bone marrow clonal plasma cell proliferation as seen in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or multiple myeloma diagnosed in 17% and 58% of cases, respectively.3 In contrast, in the pulmonary nodular form of LCDD, monoclonal light chain synthesis seems to be a localized process.8-13 A diagnosis of primary pulmonary low-grade B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma and lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma) or lung plasmacytoma was made in 5 of the 10 patients reported in the literature. In the present study, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were normal (plasma cells < 5%, preserved κ/λ ratio). Although the pulmonary lymphoid infiltrate associated with κ light chain deposits was morphologically and immunophenotypically more suggestive of BALT than B-cell neoplasm, we looked for clonality of pulmonary B cells. We hypothesized that monoclonal light chain synthesis occurred in the lung in view of the absence of recurrence of the disease after bilateral lung transplantation and of the normalization of serum-free light chain κ/λ ratio after the procedure. PCR clonality analysis disclosed a predominant B-cell clone in the lung of our 3 patients. In 2 of them, the same clonal expansion with a lower fluorescence signal was detected in the hilar or lobar lymph nodes. To exclude a tissular infiltration by a circulating disorder, we performed peripheral blood clonality analysis. It was done after lung transplantation, but we assumed that a small B-cell extrapulmonary lymphoproliferative disorder would not be cured by lung transplantation or by immunosuppressive treatment. Peripheral blood revealed a polyclonal pattern. According to the trafficking of antibody-secreting cells34 and by analogy with nondisseminated pulmonary MALT lymphoma,35 we postulate that involvement of regional lymph nodes and distant spread to other mucosal sites in cystic lung LCDD might be related to the peculiar expression of specific adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors by the clonal cells and did not correspond to a metastatic process. Although the morphologic features observed in our study do not met the histologic diagnosis criteria of MALT lymphoma as requested in the World Health Organization (WHO) lymphoma classification,36 we cannot exclude that these cases may be part of the morphologic spectrum of pulmonary MALT lymphomas.

Although it is currently acknowledged in systemic multivisceral LCDD that light chains exhibit a number of somatic mutations and/or posttranslational modifications conferring new properties to light chain protein, no study has yet been concerned with potential distinctive heavy chain features. Remarkably, we showed that the B-cell clones from our 3 patients expressed homologous IGHV/IGKV repertoire for IG rearrangement using the IGHV4-34*01/IGKV1 subgroups. The usage of a IGHV4-34/IGKV1 stereotyped receptor with closely homologous heavy and light chain CDR3 sequences raises the possibility of a common antigen-driven selection.

A restricted IG repertoire with similar heavy and light chain CDR3 as observed in cystic lung LCDD has already been reported for different types of B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Several authors have found distinct sets of stereotyped B-cell antigen receptors expressed by leukemic lymphocytes in patients with CLL.26,27,37-41 These data are highly suggestive of a role for antigen in promoting proliferation of B cells with particular surface IG. However, the causal antigens remain to be identified. Stereotyped B-cell antigen receptors were also found in subsets of marginal zone lymphomas arising in the lymph nodes42,43 and in MALT mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.25,44

In marginal zone lymphomas, the possibility of antigen-driven lymphomagenesis has been demonstrated. The risk for developing MALT lymphoma is severely increased in patients with chronic antigenic stimulation by autoantigens and/or microbial pathogens. Chronic stimulation of the immune system induces a sustained lymphoid proliferation favoring the neoplastic transformation process.45 Sjögren syndrome46 and autoimmune Hashimoto thyroiditis47 are the most frequent underlying autoimmune conditions. The list of microbial species involved in the development of lymphoproliferations has progressively grown and now comprises 5 distinct members: Helicobacter pylori, Campylobacter jejuni, Borrelia burgdorferi, Chlamydia psittaci, and hepatitis C virus (HCV), which have been associated with MALT gastric lymphoma, immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID), MALT cutaneous lymphoma, MALT ocular lymphoma, and marginal zone spleen lymphoma, respectively. All these variants of lymphoma have the same immunophenotypical features except IPSID. The malignant cells of IPSID secrete a monotypic truncated Ig α-heavy chain lacking an associated light chain.48 This fact in addition to the notion of persistent antigenic stimulation leads us to draw a parallel between IPSID and cystic lung LCDD, although there are no IG tissular deposits in IPSID. Of note, therapeutic trials have demonstrated that IPSID48 as well as gastric49,50 and cutaneous MALT lymphomas51,52 at an early stage can be cured with antibiotics alone. Similarly, interferon-α2b treatment in patients with splenic marginal zone lymphoma who are infected with HCV leads to regression of the lymphoma.53 Therefore, the evidence that our study provides clues for a putative common antigen in cystic lung LCDD is of great interest. In our patients, the search for serum anti-HCV antibodies was negative. To address the issue of the implication of bacterial respiratory infection promoting B-cell clonal expansion in cystic lung LCDD, we performed PCR amplification using universal bacterial 16S rDNA primers and templates prepared from frozen lung tissue (data not shown). No pulmonary bacterial infection could be detected. These are preliminary data that require further investigations.

The preferential usage of IGHV4-34 gene found in our 3 patients has been previously reported in several B-cell lymphoproliferations, namely subgroups of CLL,37 marginal zone lymphomas,42,54,55 mantle cell lymphoma,56 Burkitt lymphoma,56,57 and primary central nervous system lymphoma,58 and remains still controversial in large B-cell lymphoma.56,59,60 IGHV4-34 encodes autoantibodies that recognize the I/i red blood cell determinants.61 These autoantibodies are also able to interact with other antigenic structures such as DNA, cytoskeletal proteins, or Fc fragment of IgG (rheumatoid factor).62,63 They are rare in healthy individuals, although IGHV4-34 gene is expressed in the repertoire of 3% to 6% of the normal human peripheral blood B cells,61,64,65 suggesting an anergic state of these cells. In contrast with the majority of IGHV4-34–expressing entity, the IGHV4-34*01 sequences belonging to our 3 patients revealed the absence of somatic mutations. This finding is not consistent with a classical T cell–dependent antigenic stimulation of B lymphocytes and germinal center phenotype. However, such a result has already been observed in thymic44 and salivary gland66 MALT lymphomas. Moreover, some authors have established the existence of unmutated MALT lymphomas and CLLs displaying isotype switching.44,67 These data indicate that tumoral cells may arise from peculiar B cells, the activation of which could implicate a T cell–independent immune response.68

In conclusion, because the patients shared unique clinical, histologic, and molecular features, we propose that cystic lung LCDD should be considered as a distinct entity. Moreover, we show that the different pulmonary B-cell clones use a IGHV4-34/IGKV1 stereotyped receptor, molecular data strongly arguing for an antigen-driven primary pulmonary lymphoproliferation. Our results could have an important therapeutic implication since bilateral lung transplantation seems to be the only current valid therapeutic option.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof P. Gaulard and Prof F. Davi for their critical review of the paper, and Prof O. Hermine for helpful discussions. We thank Prof M. P. Lefranc for her critical review of the paper and her help in the analysis of CDR3 sequences in accordance with the international nomenclature. We thank Ludovic Cabanne, Christine Tricot, Maryse Baia, and Martine Kernaonet for their technical assistance.

Authorship

Contribution: M.C. coordinated the research and wrote the paper; H.M., M.S., and M.F. participated in the collection and analysis of the clinical data; J.D., D.D., and C.C.-B. reviewed the histologic and immunohistologic data; C.C.-B. performed FISH analysis; P.C. and J.-P.F. reviewed the paper and made corrections; and M.-H.D.-L. designed/performed research and helped write the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marie-Hélène Delfau-Larue, Service d'immunologie biologique, Hôpital Henri Mondor, 51 avenue du Maréchal de Lattre de Tassigny, 94010 Créteil Cedex, France; e-mail: marie-helene.delfau@hmn.aphp.fr.