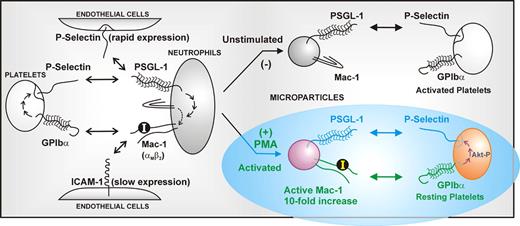

In this issue of Blood, Pluskota and colleagues reveal a new prothrombotic pathway initiated by neutrophil-derived microparticles through the interaction of the leukocyte integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2) on microparticles with its counterreceptor on platelets, GPIbα, the major ligand-binding subunit of the GPIb-IX-V complex (see figure). These findings have broad implications for the pathogenesis, monitoring, and/or future therapy of inflammatory/thrombotic disease.

All inflammatory/thrombotic vascular cells (leukocytes, platelets, endothelial cells) generate microparticles, small membrane-bound vesicles budded off from the parent cell that generally reflect that cell's surface-receptor profile. Microparticles are not just by-products of cellular activation or apoptosis, but are functional and modulate the activity of other cells. They also represent potentially selective biomarkers of diseases involving cellular perturbation.1 One important role for leukocyte-derived microparticles is to deliver clot-promoting tissue factor rapidly to a developing thrombus.2 In this case, P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) on the microparticle targets activated platelets by binding platelet P-selectin. Activated platelets are also strongly procoagulant due to increased exposure of phosphatidyl serine, the expression of coagulation factor-binding receptors, the secretion of polyphos-phates, and through glycoprotein (GP) Ibα, which acts as a molecular scaffold local-izing coagulation factors such as high-molecular-weight kininogen, factors XI and XII, and thrombin.3 Interestingly, the present findings indicate that leukocyte-derived microparticles play another poten-tial role in thrombus development by acting as a novel platelet agonist targeting GPIbα. This provides a potential explanation of how chronic inflammation can perpetuate a prothrombotic phenotype.

Pluskota and colleagues show that microparticles derived from activated neutrophils express functional Mac-1 and act as platelet agonists by virtue of Mac-1 binding platelet GPIbα. GPIbα is a constitutively expressed platelet-adhesion receptor that initiates thrombus formation at arterial shear rates by binding von Willebrand factor (VWF) or other ligands.3,4 Engagement of GPIbα by Mac-1–bearing microparticles leads to phosphorylation of the signaling protein Akt, which is an intermediary in GPIbα-dependent signaling downstream of phosphatidyl inositol (PI) 3-kinase activation, and upstream of surface expression of P-selectin and activation of αIIbβ3 (which binds fibrinogen and VWF and mediates platelet aggregation). P-selectin expressed on the activated platelets can bind PSGL-1, strengthening the association between the activated neutrophil microparticle and the platelets. It has been previously established that GPIbα directly binds activated leukocyte Mac-1,5 as well as P-selectin expressed on activated platelets/endothelial cells,3,6 enabling GPIbα-mediated platelet-leukocyte-endothelial cell crosstalk; for example, platelets strongly promote vascular adhesion of leukocytes in atherogenesis.7 Binding of P-selectin on activated platelets or platelet microparticles to leukocyte PSGL-1 initiates signals activating Mac-1, thereby enabling integrin-dependent adhesion to endothelial cells via intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), or to mural platelets via GPIbα (see figure).

The expression on neutrophil-derived microparticles of the integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2) in an active conformation provides a new mechanism for leukocyte-platelet crosstalk. In contrast to microparticles from resting neutrophils, microparticles from PAF- or PMA-stimulated neutrophils express Mac-1 where the insert or ‘I’ domain on the αM subunit is in a high-affinity ligand-binding form. This can bind platelet GPIbα (the major ligand-binding subunit of the GPIb-IX-V complex), leading to platelet activation and P-selectin expression, which reinforces association via microparticle PSGL-1.

The expression on neutrophil-derived microparticles of the integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2) in an active conformation provides a new mechanism for leukocyte-platelet crosstalk. In contrast to microparticles from resting neutrophils, microparticles from PAF- or PMA-stimulated neutrophils express Mac-1 where the insert or ‘I’ domain on the αM subunit is in a high-affinity ligand-binding form. This can bind platelet GPIbα (the major ligand-binding subunit of the GPIb-IX-V complex), leading to platelet activation and P-selectin expression, which reinforces association via microparticle PSGL-1.

One of the key findings from this study is that, whereas microparticles derived from unstimulated neutrophils contain relatively low levels of Mac-1 in an inactive state, microparticles derived from PMA- or PAF-activated neutrophils contain approximately10-fold enrichment of Mac-1 present in an activated state, where the insert or “I” domain in the αM subunit is in a high-affinity ligand-binding form. This was established by binding of conformation-dependent antibodies or the Mac-1 ligand, fibrinogen. These relative levels of inactive/active Mac-1 in microparticles are thought to depend on lipid raft constituency before or after stimulation. This is because microparticles are likely derived from these membrane domains, and activated Mac-1 is enriched in rafts following neutrophil stimulation. There is thus a built-in differential adhesive capacity of microparticles from unstimulated versus activated neutrophils to facilitate interaction with either activated platelets (via PSGL-1/P-selectin) or resting platelets (via active Mac-1/GPIbα), respectively. This implies that microparticle-dependent platelet activation occurs under conditions where neutrophils are also activated; conversely, microparticles generated from quiescent neutrophils (expressing inactive Mac-1) would be limited to interacting only with activated platelets (expressing surface P-selectin).

What, then, is the relevance of these new findings to inflammation and thrombosis, and is there potential diagnostic value in measuring the proportion of total neutrophil-derived microparticles expressing activated Mac-1 as a biomarker for pathological inflammation/thrombosis? This remains to be determined, but the new discoveries by Pluskota and colleagues demonstrate a clear prothrombotic functional pathway for this microparticle subtype.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal