Abstract

The current paradigm in Plasmodium falciparum malaria pathogenesis states that young, ring-infected erythrocytes (rings) circulate in peripheral blood and that mature stages are sequestered in the vasculature, avoiding clearance by the spleen. Through ex vivo perfusion of human spleens, we examined the interaction of this unique blood-filtering organ with P falciparum–infected erythrocytes. As predicted, mature stages were retained. However, more than 50% of rings were also retained and accumulated upstream from endothelial sinus wall slits of the open, slow red pulp microcirculation. Ten percent of rings were retained at each spleen passage, a rate matching the proportion of blood flowing through the slow circulatory compartment established in parallel using spleen contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in healthy volunteers. Rings displayed a mildly but significantly reduced elongation index, consistent with a retention process, due to their altered mechanical properties. This raises the new paradigm of a heterogeneous ring population, the less deformable subset being retained in the spleen, thereby reducing the parasite biomass that will sequester in vital organs, influencing the risk of severe complications, such as cerebral malaria or severe anemia. Cryptic ring retention uncovers a new role for the spleen in the control of parasite density, opening novel intervention opportunities.

Introduction

The pathogenesis of malaria involves multiple parasite and host factors.1 Spleen filtering and immune functions have a major impact on the course of plasmodial infection in experimental models.2,3 In malaria-endemic countries, splenectomy predisposes to fever, to more frequent and higher parasitemia (including circulating mature forms), and may reactivate latent plasmodial infections.4,5 Despite relatively few published data (reviewed by Bach et al5 ), clinicians include malaria in the list of infectious diseases justifying increased awareness in splenectomized nonimmune patients.6 Because key features may differ between animal and human plasmodial infection and because detailed exploration of the human spleen is limited by ethical and technical constraints,7 the fine interactions between Plasmodium falciparum–infected red blood cells (iRBCs) and the human spleen microcirculatory structures have been explored only indirectly8,9 or postmortem.10 Therefore, the mechanisms underlying the putative spleen protective or pathogenic effects during human malaria remain essentially speculative.

The architecture of the spleen red pulp (RP) permits intimate scrutiny of red blood cells (RBCs), leading to selective retention of abnormal or senescent RBCs within the RP.11 To reenter the venous system, RBCs leaving the reticular meshwork of the RP must cross the narrow interendothelial slits in walls of the venous sinuses. This process requires RBCs to undergo considerable deformation: if cells are not sufficiently deformable, they are retained upstream from the venous sinus wall.11 Such RBC-processing functions are expected to act on RBCs hosting Plasmodium.12 Parasite development inside the RBC results in an altered host-cell membrane, which presents new structural, functional, and antigenic properties, some of which are related to the peculiar severity of P falciparum infections.13,14 Ring-iRBCs are the predominant P falciparum forms found in the circulation, in contrast with tissue sequestration of cytoadhering mature iRBCs. Deformability of mature-iRBC is markedly reduced, which would induce the retention in the spleen of those escaping sequestration in “classical” vascular beds.15 In this context, a quantified spleen circulatory framework is an essential prerequisite for a consistent understanding of malaria pathogenesis. Previous experimental determination of the proportion of spleen blood flow directed to the filtering beds of the open circulation in animals ranged from 90%16 to 10%,11 warranting direct in vivo explorations in humans.

We report here on complementary dimensions of human spleen physiology and malaria pathogenesis following 2 conceptually connected approaches: in vivo imaging in healthy volunteers and challenge of an ex vivo human spleen perfusion system7 with cultured iRBCs. We provide the first in vivo confirmation of a 2-compartment blood circulation in the human spleen, the slower compartment accounting for 10% of the flow. We show that, at each spleen passage, 10% of a previously ignored subpopulation of ring-iRBCs is retained in the slow, open circulatory structures of the human spleen RP, most probably by a mechanical process. These results uncover heterogeneity of ring stage parasites and provide a new vision of RBC filtration by the spleen, shedding new light on control of parasite multiplication and RBC loss in malaria patients.

Methods

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in human volunteers

Sixteen 18- to 50-year-old healthy male volunteers were enrolled according to the following inclusion criteria: no risk factor for atheroma (ie, normal arterial pressure, no present or past smoking habit, normal serum cholesterol level), no previous history of abdominal surgery, no present or past significant health problem (normal physical examination, normal serum creatinine, aspartate aminotransferase, and bilirubin levels, and absence of antibody to HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus), normal splenic macrovascular structures as assessed by conventional ultrasonography and Doppler, and no clinical or biologic indication of RBC disease, including normal blood cell count, serum haptoglobin, and hemoglobin electrophoresis. The study was approved by the Necker Hospital Investigational Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. An ultrasound contrast agent (Sonovue; Bracco, Milano, Italy) was injected intravenously at a constant infusion rate of 1 mL/min. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography was performed using a Philips HDI 5000 (Philips, Bothell, WA). The spleen was imaged with a linear transducer (L10-5) using pulse-inversion imaging at low mechanical index to minimize microbubble destruction,17 starting 2 minutes after the beginning of the infusion. Each acquisition was repeated 3 times, and the raw data were transferred to a personal computer for further quantification. Each cineloop was quantified using HDI Lab (Philips), software that takes into account the compression map and allows quantification in linear units. The signal intensity was calculated from a region of interest located in the subcapsular area. The region of interest position was moved to compensate for the respiratory movements and subcutaneous artifacts. The time-intensity curve was exported into Deltagraph (Red Rock Software, Salt Lake City, UT). The data were fitted using a bi-exponential model. The quality of the fit was estimated using the correlation coefficient between the data and the model.

Human spleen retrieval

Spleens were retrieved and processed as described.7 Medical and surgical care was not modified, and patient written consent was obtained. The project was approved by the Ile-de-France II Investigational Review Board. All patients (7 females, 3 males), 37 to 74 years of age, underwent left splenopancreatectomy for pancreas disease: neuroendocrine tumor (3), proven or suspected adenocarcinoma (3), cyst (1), unspecified tumor (2), or chronic pancreatitis (1). The spleen was macroscopically and microscopically normal in all cases. During a 30- to 90-minute period of warm ischemia linked to the surgical procedure, the main splenic artery was cannulated once the macroscopic aspect of the spleen had been examined by the pathologist, and a preexperiment biopsy had been performed whenever required. The spleens were flushed with cold Krebs-albumin solution for transport to the laboratory.

Parasites

P falciparum Palo-Alto (FUP-CB13 ) and D1018 were cultured as described.19 Panning on human amelanotic melanoma cells (C32)20 was repeated until a cytoadherent rate of more than 5 iRBCs per C32 cell was obtained. Cytoadherent iRBCs were amplified, grossly synchronized by gel flotation until complete reinvasion occurred over less than 16 hours, and then stored in liquid nitrogen as large more than 3-mL aliquots. Less than 7 days before the spleen challenge, aliquots were thawed, and parasites were allowed to reinvade uninfected RBCs. Less than 14 hours before the spleen challenge, rings were eliminated by the gel flotation method, and mature forms were allowed to reinvade in recently collected (< 7 days) and washed RBCs so as to obtain 7 to 40 mL of packed RBCs at 2% to 7% parasitemia, which were washed once in RPMI before introduction into the perfusate.

Ex vivo spleen perfusion

Isolated-perfused spleen experiments were performed as described,7 in a Plexiglas chamber maintained at 37°C by a regulated warmed air flow. Briefly, once in the laboratory (cold ischemia time, 60-90 minutes), the spleen was connected to the perfusion device, and a progressive warming from 6°C to 10°C to 37°C was performed by increasing the Krebs-albumin medium flow from 1 mL/min to 50 to 150 mL/min over 40 to 60 minutes. During this adaptation period, the patient's RBCs were flushed from the spleen (hematocrit at the end of the warming period < 0.1%). When the spleen temperature reached 35°C, uninfected O+ RBCs were added (5%-10% final hematocrit) and allowed to circulate for 30 to 60 minutes. Glucose, Na, K, concentrations, O2, CO2 partial pressures, and pH were monitored in the vein, artery, and reservoir every 10 to 30 minutes using a iStat device (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). At steady state, key physiologic markers were maintained in the following ranges: perfusate flow 0.8 to 1.2 mL/g of perfused spleen parenchyma per minute, temperature of the spleen capsule 36.7°C to 37.2°C, Na 135 to 148 mEq/L, K 4 to 5 mEq/L, glucose 4 to 12 mM, pH 7.2 to 7.35, hematocrit 4% to 10%, and arterial-venous oxygen partial pressure decay 60 to 120 mmHg. Finally, a mixture of more than 32-hour schizont-iRBCs (40 ± 8 hours postinvasion) and less than 14-hour ring-iRBCs (7 ± 7 hours postinvasion) at 0.2% to 6% parasitemia was introduced in the circulating system for 2 hours after normal RBCs had been rinsed out for 5 to 10 minutes (hematocrit before the introduction of iRBCs < 0.2%). Parasitemia was quantified on Giemsa-stained thin smears or by flow cytometric analysis after staining of iRBCs with Hoechst 33342 (diluted 1:1000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA; LSR; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed using CELLQuest software (BD Biosciences).

Parasite staging and counting

The spleen tissue was fixed and processed exactly as described.7 The individual parasite nuclei, cytoplasm, and malaria pigment were readily identified within the spleen tissue. iRBC stages were differentiated according to the following criteria: ring-iRBCs, light brown dot (nucleus) less than 1 μm with thin blue cytoplasm or pale round zone less than half of the erythrocyte; schizont-iRBCs, light brown dot more than 1 μm or more than 1 brown dot with thick blue cytoplasm diameter half of erythrocyte chamber; extra-erythrocytic parasite remnant, brown dot(s) not surrounded by red staining. For each spleen slide, iRBCs were counted within both the perifollicular zone and the red pulp adjacent to at least 3 follicles. Follicles with a clear differentiation between the white pulp, the adjacent perifollicular zone, and the red pulp were selected for counting. Ring- and schizont-iRBCs were counted and localized on approximately 150 photographs (at least 4000 RBCs) for each spleen.

Pictures were acquired on a Nikon E 800 microscope, using a Nikon digital still DXM 1200 camera controlled by ACT-1 version 2 Nikon software (all from Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Images were visualized with a Plan Apo 40×/0.95 DiCM or a Plan Apo 100×/1.40 oil-immersion DiCM objective lens (Nikon).

Transmission and scanning electron microscopy

At the end of perfusion, spleen samples (1 mm3) were fixed overnight at 4°C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1% paraformaldehyde in 0.08 M cacodylate buffer supplemented with CaCl2 (0.05%). For transmission electron microscopy, fixed samples were rinsed 3 times with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed with 1% osmium tetraoxide, 1.5% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed again with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. The samples were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol bath (25%-100%) and overnight in a mixture of Epon 812/propylene oxide at room temperature. After being embedded in Epon 812, samples were polymerized for 48 hours at 60°C. Ultrathin sections were prepared using a Leica ultracut UCT microtome and examined with a JEOL 1200 EX electron microscope operating at 80 kV. For scanning electron microscopy, fixed pieces were washed 3 times for 10 minutes in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, postfixed for 1 hour in 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide, and 1.5% potassium ferricyanide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. Spleen sections were dehydrated through a graded series of 25%, 50%, 75%, and 95% acetone solution for 10 minutes (each time). Samples were then dehydrated 3 times for 10 minutes each time in 100% acetone followed by critical point drying with CO2. Dried specimens were sputtered with 22-nm gold palladium, examined, and photographed with a JEOL JSM 6700F field emission scanning electron microscope operating at 5 kV or 7 kV. Images were acquired with the upper SE detector and the lower secondary detector.

Measurement of RBC deformability

RBC and iRBC deformability was measured by ektacytometry using a laser-assisted optical rotational cell analyzer (LORCA; Mechatronics, Hoorn, The Netherlands) as previously described.21 The unit of RBC deformability, namely, the elongation index (EI), was defined as the ratio between the difference between the 2 axes of the ellipsoid diffraction pattern and the sum of these 2 axes. RBC deformability was assessed over a range of shear stresses (0.3-30 Pa), including 1.7 Pa, which corresponds approximately to the intravenous stress on the arterial side of the circulation,14 and 30 Pa, which occurs in the sinusoids of the spleen where RBCs have to squeeze through the small intercellular gaps.

Erythrocyte surface immunofluorescence assay

This assay was performed to detect surface-iRBCs parasite proteins, as described. iRBCs in suspension in phosphate-buffered saline were prepared from cultures. Labeling of RBC surface parasite antigen was performed with sera from hyperimmune African adults (a kind gift from P. Druilhe, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France; 1:100 serum dilution in phosphate-buffered saline/1% bovine serum albumin) followed by Alexafluor 488–conjugated goat anti–human affinity-purified IgG (diluted 1:200; Invitrogen). Parasite nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (diluted 1:1000; Invitrogen). Slides were mounted with Vectashield medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope, using an Axiocam HRc camera controlled by Zeiss Axiovision software (all from Carl Zeiss, Heidelberg, Germany).

Surface iodination of iRBCs

Highly synchronized mature stage iRBCs previously selected on cell C32 by panning procedure were enriched up to 80% by the gelatin flotation technique and then diluted with fresh erythrocytes to obtain approximately 20% ring-iRBCs at the next cycle. Surface iodination was done using the lactoperoxidase method.22 The culture was stopped 14 hours after reinvasion. Proteins were sequentially extracted with 1% Triton X-100, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Protease treatment of the samples (tosyl-L-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone–treated trypsin and α-chymotrypsin tosyl-lysine-chloromethyl ketone; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was performed as described.22 Samples iodinated were separated on a 5% to 17.5% gradient acrylamide gel. Autoradiography was done using Kodak Bio Max MS1 film. Prestained protein markers were purchased from Invitrogen and New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA).

Cytoadherence assay

The cytoadherence of iRBC to C32 cells, which express both the putative receptor molecule CD36 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1, was studied as previously described.20 In brief, a monolayer of C32 cells was prepared in 25-cm3 cell culture flask (Corning, NY). RBCs suspended at a concentration of 5 × 106 iRBC/mL in cytoadhesion medium at pH 6.8 were added to cell culture flask and gazed (1% O2, 3% CO2, and 96% N2) during 15 seconds, and this was incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes with gentle rocking every 5 minutes. At the end of the incubation, the cell culture flask was gently rinsed 4 times in RPMI 1640 medium. The monolayer was fixed in methanol, stained with 2% Giemsa, and examined microscopically. The number of iRBC adherent to 1000 melanoma cells was counted. Results are expressed as the number of iRBC that adhered to 100 C32 cells.

Statistical analysis

We used the Student paired t test for statistical analysis; P values less than .05 were considered significant. Compartment data analysis was performed using the WinNonLin software (version 5.1; Pharsight, Mountain View, CA).

Results

Circulatory compartments in the human spleen

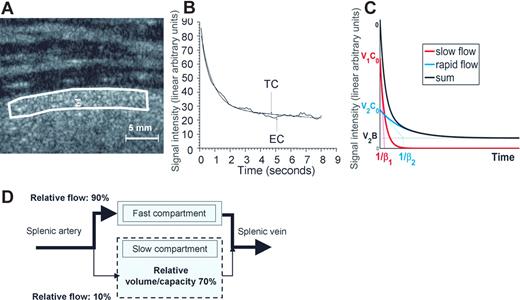

The circulatory pattern of the human spleen was explored using contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in 16 volunteers. Two minutes after starting the infusion of contrast agent (ie, once a stable concentration of microbubbles was achieved), the spleen was studied using low mechanical index pulse inversion imaging. Despite the use of this low acoustic energy, a certain amount of microbubbles was destroyed all along the continuous exposure of the spleen to the ultrasound beam. The time-intensity curve reflected the decrease in signal intensity (Figure 1; “Methods”). The model that displayed the best fit with the experimental decay in the 16 volunteers combined 2 exponentials (correlation coefficient R2 > 0.96 in all cases). The bi-exponential function can be expressed as

where the first and second terms correspond to a slow- and a rapid-flow compartment, respectively. C0 refers to the initial (t = 0) microbubble concentration and was considered identical in both compartments. V1 and V2 refer to the relative fractional volumes (V1 + V2 = 1), and β1 and β2 to the microbubble mean velocity in each compartment, respectively. Analysis of the experimental curves provided the following values: the Y intercept of each one-compartment exponential curve (Y10 and Y20) corresponds to C0V1 and C0V2, whereas 1/β1 and 1/β2 correspond to the exponential-characteristic times. In the slow compartment, the averaged (SD, range) relative fractional volume of the slow compartment was 70.6% (9.6%, 51.5%-84.4%) and the averaged (SD, range) relative fractional flow was 10.12% (4.40%, 3.99%-16.47%; Figure 1). Altogether, these observations strongly support the existence of a dual microcirculatory organization of the human spleen (Figure 1), with approximately 10% of the blood input flowing through the slow compartment (Figures 1,2).

Contrast ultrasound analysis of blood circulation in the human spleen parenchyma. (A) Enhancement of the ultrasound signal intensity in the spleen of a human volunteer receiving a constant perfusion of Sonovue microbubbles. (B) The ultrasound-induced decrease of signal intensity43 in a subcapsular zone (white line in panel A) was studied for at least 8 seconds. The best fit to the resulting experimental signal-time curve (EC) was obtained with a bi-exponential curve (TC), as shown on this typical example (the correlation co-efficient R2 was > 0.96 in all 16 volunteers). (C) Bi-exponential mathematical model of signal intensity vs time N(t) = V1(C0exp(−β1t)) + V2(B + (C0−B)exp(−β2t)), where the first and second terms correspond to a slow- and a rapid-flow compartment, respectively. (D) Schematic representation of the blood circulation in the human spleen parenchyma derived from these observations.

Contrast ultrasound analysis of blood circulation in the human spleen parenchyma. (A) Enhancement of the ultrasound signal intensity in the spleen of a human volunteer receiving a constant perfusion of Sonovue microbubbles. (B) The ultrasound-induced decrease of signal intensity43 in a subcapsular zone (white line in panel A) was studied for at least 8 seconds. The best fit to the resulting experimental signal-time curve (EC) was obtained with a bi-exponential curve (TC), as shown on this typical example (the correlation co-efficient R2 was > 0.96 in all 16 volunteers). (C) Bi-exponential mathematical model of signal intensity vs time N(t) = V1(C0exp(−β1t)) + V2(B + (C0−B)exp(−β2t)), where the first and second terms correspond to a slow- and a rapid-flow compartment, respectively. (D) Schematic representation of the blood circulation in the human spleen parenchyma derived from these observations.

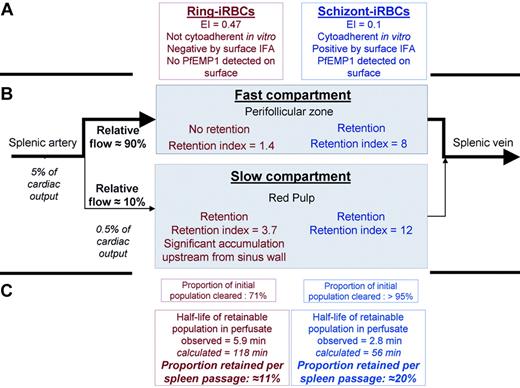

P falciparum–infected RBCs through the fast and slow circulatory compartments of the perfused human spleen. Schematic representation of observations in the ex vivo human spleen model challenged with cultured iRBCs, using the circulatory features extracted from in vivo imaging in human volunteers as a framework (Figure 1). Ring- and schizont-iRBCs differed in their main phenotypic characteristics, with ring-iRBCs displaying no cytoadherent properties in vitro and no observable surface modifications (A). In the fast compartment, corresponding to the perifollicular zone on histologic sections, only schizont-iRBCs were retained, whereas both ring- and schizont-iRBcs were retained in the slow compartment, corresponding to the red pulp (B). This resulted in significantly different clearance rates. The similarity between the proportion of blood flowing to the slow compartment (10.2%) and the proportion of retainable ring-iRBCs retained in the same compartment (11%) was striking. The quantitative dimension of the spleen microcirculatory framework is important. Because 5% of the cardiac output goes to the spleen, a given RBC will enter the spleen every 20 minutes. The slow compartment accounts for only 10% of the spleen plasma flow, which corresponds to 10% to 20% of spleen RBC flow (depending on the intensity of plasma skimming effect11 ). Therefore, the quality control of the deformability of a given RBC occurs every 100 to 200 minutes. This fits with the 60-minute half-life of stiff-heated RBCs previously observed in healthy controls.39 The order of magnitude of those previous clinical observations perfectly fits our framework (C). In addition, according to our volume estimates (Figure 1), an average 150-g spleen contains approximately 100 g of red pulp (70% of 150 g). The physiologic daily input of senescent RBCs to the spleen (1% of total RBC biomass ∼ 20 mL/day) thus corresponds to approximately 20% of the red pulp volume. During acute P falciparum malaria, parasitemia more than 5% is not uncommon. The input of ring-iRBCs to the spleen may therefore exceed the red pulp volume, probably saturating the slow circulatory compartment. The risk of saturation probably becomes significant when the ring-iRBC biomass at least equals the physiologic daily input of senescent RBCs, ie, at a peripheral parasitemia of approximately 1%. Saturation is expected to transiently reduce spleen filtering function and to induce abrupt changes in the slow/fast circulation balance. Those mechanisms, along with sequestration of mature iRBCs in the PFZ and red pulp sinus lumens, are potential strong determinants of both splenomegaly and outcome in acute malaria.

P falciparum–infected RBCs through the fast and slow circulatory compartments of the perfused human spleen. Schematic representation of observations in the ex vivo human spleen model challenged with cultured iRBCs, using the circulatory features extracted from in vivo imaging in human volunteers as a framework (Figure 1). Ring- and schizont-iRBCs differed in their main phenotypic characteristics, with ring-iRBCs displaying no cytoadherent properties in vitro and no observable surface modifications (A). In the fast compartment, corresponding to the perifollicular zone on histologic sections, only schizont-iRBCs were retained, whereas both ring- and schizont-iRBcs were retained in the slow compartment, corresponding to the red pulp (B). This resulted in significantly different clearance rates. The similarity between the proportion of blood flowing to the slow compartment (10.2%) and the proportion of retainable ring-iRBCs retained in the same compartment (11%) was striking. The quantitative dimension of the spleen microcirculatory framework is important. Because 5% of the cardiac output goes to the spleen, a given RBC will enter the spleen every 20 minutes. The slow compartment accounts for only 10% of the spleen plasma flow, which corresponds to 10% to 20% of spleen RBC flow (depending on the intensity of plasma skimming effect11 ). Therefore, the quality control of the deformability of a given RBC occurs every 100 to 200 minutes. This fits with the 60-minute half-life of stiff-heated RBCs previously observed in healthy controls.39 The order of magnitude of those previous clinical observations perfectly fits our framework (C). In addition, according to our volume estimates (Figure 1), an average 150-g spleen contains approximately 100 g of red pulp (70% of 150 g). The physiologic daily input of senescent RBCs to the spleen (1% of total RBC biomass ∼ 20 mL/day) thus corresponds to approximately 20% of the red pulp volume. During acute P falciparum malaria, parasitemia more than 5% is not uncommon. The input of ring-iRBCs to the spleen may therefore exceed the red pulp volume, probably saturating the slow circulatory compartment. The risk of saturation probably becomes significant when the ring-iRBC biomass at least equals the physiologic daily input of senescent RBCs, ie, at a peripheral parasitemia of approximately 1%. Saturation is expected to transiently reduce spleen filtering function and to induce abrupt changes in the slow/fast circulation balance. Those mechanisms, along with sequestration of mature iRBCs in the PFZ and red pulp sinus lumens, are potential strong determinants of both splenomegaly and outcome in acute malaria.

Clearance of iRBCs by isolated-perfused human spleens

Isolated-perfused human spleens were perfused with highly synchronous parasite cultures at the schizont stage (40 ± 8 hours after invasion) or at the ring stage (7 ± 7 hours after invasion). Sequential Giemsa-stained thin films of the perfusate showed that circulating schizont-iRBC and (unexpectedly) ring-iRBC parasitemia rapidly decreased. Within 10 and 20 minutes, schizont- and ring-iRBC parasitemias fell to 4.5% (range, 0%-12.9%) and 26.3% (range, 22.9%-35.4%) of their initial values, respectively (Figures 3A; S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Complete clearance of the schizont-iRBCs was rapid, whereas ring-iRBC parasitemia decreased at a slower rate and reached a plateau (Figures 3A; S1). In contrast with schizont-iRBCs, ring-iRBCs displayed neither knobs nor iodinatable parasite proteins on their surface (Figures 3B-D; S2), and no cytoadherence was noticed on C32 human melanoma cells (data not shown) or on spleen histologic examination (Figure 4H,I).

Clearance of iRBCs by the isolated-perfused human spleen. (A) Parasitemia of P falciparum FUP schizont-iRBCs (▲) and ring-iRBCs (●) in the perfusate during 120 minutes of perfusion in 1 of 6 independent experiments with isolated-perfused human spleens (all 6 experiments shown in Figure S1, a1-6). (B) Transmission electron microscopy of an end-experiment spleen sample showing a schizont-iRBC (S). (B,C) Bar represents 1 with knobs (C, arrows) in the lumen of a sinus (B, SL) of the red pulp, and a knobless ring-iRBC (B-D, R), in the cords (B, Co). Another example of retained ring-iRBC is shown in Figure 4H,I.

Clearance of iRBCs by the isolated-perfused human spleen. (A) Parasitemia of P falciparum FUP schizont-iRBCs (▲) and ring-iRBCs (●) in the perfusate during 120 minutes of perfusion in 1 of 6 independent experiments with isolated-perfused human spleens (all 6 experiments shown in Figure S1, a1-6). (B) Transmission electron microscopy of an end-experiment spleen sample showing a schizont-iRBC (S). (B,C) Bar represents 1 with knobs (C, arrows) in the lumen of a sinus (B, SL) of the red pulp, and a knobless ring-iRBC (B-D, R), in the cords (B, Co). Another example of retained ring-iRBC is shown in Figure 4H,I.

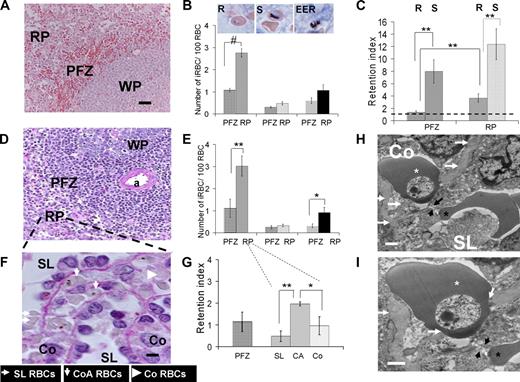

Analysis of P falciparum–iRBC deposition in the human spleen. (A,B) Mean (SEM) number of iRBCs/100 RBC in the perifollicular zone (PFZ) or in the red pulp (RP) for ring-iRBCs (R, in PFZ, in RP), schizont-iRBCs (S, in PFZ, in RP), or extra-erythrocytic parasite remnants (EER, in PFZ, in RP) subpopulations (mean from 6 isolated-perfused human spleen experiments, Giemsa-stained sections; WP indicates white pulp). Bar represents 50 μm. Typical aspects of each parasite development stage are shown on the inserts (middle column). (C) Retention index (RI = (“number of iRBCs/100 RBCs” as in panel B)/(circulating parasitemia at the end of the corresponding experiment)) for ring-iRBCs (R) or schizont-iRBCs (S) either in the PFZ or in the RP. An RI of 1 (black dotted line) corresponds to absence of retention. (D,E) Same approach as in panels A,B, but using PAS staining (a indicates central artery). (F) Purple PAS-stained section (bar represents 5 μm) showing the basal membrane of venous sinuses. Working classification of RBC deposition in the spleen red pulp: in the sinus lumen (SL), in the cords in direct contact with the sinus wall basal membrane (cordal abluminal, CoA), or in the cords but without contact with the basal membrane (cordal stricto sensu, Co). (G) RI for ring-iRBCs using the working classification of RBC deposition in the RP defined in panel F. (H,I) Transmission electron microscopy of a human isolated-perfused spleen sample showing a ring-iRBCs (white star) and an uninfected RBC (black star) upstream and downstream of an interendothelial slit (black arrows), respectively. This disposition reflects the cord- (Co) to-sinus lumen (SL) circulation of RBC in the spleen red pulp. The knobless membrane of the ring-iRBC is very close to the sinus wall basal membrane (white arrows). *P < .05, **P ≤ .01, #P < .001, statistically significant difference.

Analysis of P falciparum–iRBC deposition in the human spleen. (A,B) Mean (SEM) number of iRBCs/100 RBC in the perifollicular zone (PFZ) or in the red pulp (RP) for ring-iRBCs (R, in PFZ, in RP), schizont-iRBCs (S, in PFZ, in RP), or extra-erythrocytic parasite remnants (EER, in PFZ, in RP) subpopulations (mean from 6 isolated-perfused human spleen experiments, Giemsa-stained sections; WP indicates white pulp). Bar represents 50 μm. Typical aspects of each parasite development stage are shown on the inserts (middle column). (C) Retention index (RI = (“number of iRBCs/100 RBCs” as in panel B)/(circulating parasitemia at the end of the corresponding experiment)) for ring-iRBCs (R) or schizont-iRBCs (S) either in the PFZ or in the RP. An RI of 1 (black dotted line) corresponds to absence of retention. (D,E) Same approach as in panels A,B, but using PAS staining (a indicates central artery). (F) Purple PAS-stained section (bar represents 5 μm) showing the basal membrane of venous sinuses. Working classification of RBC deposition in the spleen red pulp: in the sinus lumen (SL), in the cords in direct contact with the sinus wall basal membrane (cordal abluminal, CoA), or in the cords but without contact with the basal membrane (cordal stricto sensu, Co). (G) RI for ring-iRBCs using the working classification of RBC deposition in the RP defined in panel F. (H,I) Transmission electron microscopy of a human isolated-perfused spleen sample showing a ring-iRBCs (white star) and an uninfected RBC (black star) upstream and downstream of an interendothelial slit (black arrows), respectively. This disposition reflects the cord- (Co) to-sinus lumen (SL) circulation of RBC in the spleen red pulp. The knobless membrane of the ring-iRBC is very close to the sinus wall basal membrane (white arrows). *P < .05, **P ≤ .01, #P < .001, statistically significant difference.

Heterogeneity of ring-iRBCs revealed by the spleen challenge

Partial clearance of ring-iRBCs could reflect their slower circulation through the spleen or their stable retention in the spleen. To clarify this issue, ring-iRBC preparations were split, with one part immediately perfused in the spleen and a second part kept at 37°C in Krebs-albumin medium (control “spleen naive” cells). Forty minutes (ie, approximately 40 spleen passages) after starting perfusion, the unretained cells were collected from the perfusate. These “spleen passaged” and the “spleen naive” populations were labeled with a different PKH each, pooled, and reintroduced into the spleen. Sequential samples from the perfusion system were next analyzed using flow cytometry (Figure 5). The mean (SD) half-life of “spleen-naive” ring-iRBCs (5.7 ± 3.1 minutes, 2 independent experiments) was similar to that observed during 6 previous experiments (“Modeling iRBC clearance”). In contrast, the “spleen passaged” ring-iRBCs were not cleared (Figure 5C,D). This indicates that ring-iRBCs indeed consist of 2 distinct subpopulations: one retained in the spleen and one flowing through. This heterogeneity of the ring-iRBCs population with regard to spleen retention was stable over time in our culture conditions and fairly independent of the initial parasitemia introduced in the perfused spleen (Figures 3A; S1). It was also independent of the parasite strain because similar results were obtained with D10 (data not shown).

Modeling of ring-iRBC clearance during “circulation” and “circulation-recirculation” experiments. The uncovering of 2 ring-iRBC subpopulations. (A-C) Modeling of ring-iRBC parasitemia in the perfusate, shown by a theoretical example: one-compartment without a residual parasitemia (A), 2 compartments without a residual parasitemia (B, the plain line corresponds to the bi-exponential curve, the dotted lines to the mono-exponential curves), and 1 compartment with a residual parasitemia (C, plateau phase). The evaluation of the goodness of fit and the estimated parameters was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the variability (VC) of the parameter estimates (the lower the AIC and VC values, the more parsimonious the model), and the random distribution of weighted residuals between measured and predicted concentrations with respect to time. Individual values are shown in Table S1. The AIC was lower for the 2-compartment model and the 1-compartment model with residual parasitemia than for the 1-compartment model without a residual parasitemia. However, for a 2-compartment model, the coefficient of variation of the second half-life parameter was not significant (> 100%). So, the 1-compartment model with residual parasitemia was the best model. (D,E) “Circulation-recirculation” experiments. Part of the iRBC and RBC population prepared for a spleen challenge (“Spleen naive” population) was kept at 37°C in perfusion medium, whereas the other part was perfused through the spleen. (D) Forty minutes after the perfusion onset, iRBCs and RBCs were retrieved from the circulating perfusate (D, “Spleen passaged” population). Both populations were differentially labeled using either PKH-26 or PKH-76 and then pooled and reintroduced into the perfusate 110 to 120 minutes after the initial perfusion step. Clearance kinetics of each iRBC subpopulation established using flow cytometry showing that spleen “naive” ring-iRBCs were cleared, whereas iRBCs previously submitted to approximately 40 spleen passages were not. The most parsimonious model of the kinetics of the “spleen naive” population was again 1 compartment with a residual parasitemia. Mean (individual values) AIC and half-life from 2 independent experiments were similar to that observed during the 6 previous “circulation” experiments (E). The most parsimonious model for the “spleen passaged” population was a residual parasitemia without elimination (Table S1).

Modeling of ring-iRBC clearance during “circulation” and “circulation-recirculation” experiments. The uncovering of 2 ring-iRBC subpopulations. (A-C) Modeling of ring-iRBC parasitemia in the perfusate, shown by a theoretical example: one-compartment without a residual parasitemia (A), 2 compartments without a residual parasitemia (B, the plain line corresponds to the bi-exponential curve, the dotted lines to the mono-exponential curves), and 1 compartment with a residual parasitemia (C, plateau phase). The evaluation of the goodness of fit and the estimated parameters was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the variability (VC) of the parameter estimates (the lower the AIC and VC values, the more parsimonious the model), and the random distribution of weighted residuals between measured and predicted concentrations with respect to time. Individual values are shown in Table S1. The AIC was lower for the 2-compartment model and the 1-compartment model with residual parasitemia than for the 1-compartment model without a residual parasitemia. However, for a 2-compartment model, the coefficient of variation of the second half-life parameter was not significant (> 100%). So, the 1-compartment model with residual parasitemia was the best model. (D,E) “Circulation-recirculation” experiments. Part of the iRBC and RBC population prepared for a spleen challenge (“Spleen naive” population) was kept at 37°C in perfusion medium, whereas the other part was perfused through the spleen. (D) Forty minutes after the perfusion onset, iRBCs and RBCs were retrieved from the circulating perfusate (D, “Spleen passaged” population). Both populations were differentially labeled using either PKH-26 or PKH-76 and then pooled and reintroduced into the perfusate 110 to 120 minutes after the initial perfusion step. Clearance kinetics of each iRBC subpopulation established using flow cytometry showing that spleen “naive” ring-iRBCs were cleared, whereas iRBCs previously submitted to approximately 40 spleen passages were not. The most parsimonious model of the kinetics of the “spleen naive” population was again 1 compartment with a residual parasitemia. Mean (individual values) AIC and half-life from 2 independent experiments were similar to that observed during the 6 previous “circulation” experiments (E). The most parsimonious model for the “spleen passaged” population was a residual parasitemia without elimination (Table S1).

Modeling iRBC clearance

The kinetics of iRBC parasitemia in the perfusate was modeled using either a one- or 2-compartment model, without or with a residual parasitemia (plateau phase; Figure 5A-C). A 1-compartment model without a residual parasitemia had the best performance to describe schizont-iRBC kinetics (Figure 5C). The kinetics of ring-iRBCs in the perfusate was best described by a one-order clearance phase of a “Retainable” subpopulation (∼74% of input) alongside a free circulation of a “Flow-Trough” subpopulation (∼26% of input; Figure 5; Table S1). This model fitted with circulation-recirculation observations (“Heterogeneity of ring-iRBCs revealed by the spleen challenge”) and moreover allowed a simple determination of the proportion of retained iRBCs. This is consistent with initial heterogeneity of the population of ring-iRBCs used for challenge shown in “Heterogeneity of ring-iRBCs revealed by the spleen challenge.” The mean clearance half-life of the “Retainable” ring-iRBCs subpopulation (5.9 minutes, 95% CI, 2.0-9.4) was approximately 2-fold greater than the clearance half-life of schizont-iRBCs (2.8 minutes, 95% CI, 1.5-3.9), suggesting at least partially different respective clearance mechanisms. The 5.9-minute clearance half-life of the retainable ring-iRBCs fits with the removal of approximately 11% of the retainable input at each spleen passage, assuming that each RBC crossed the isolated-perfused human spleen every minute.7

Retention of ring-iRBCs in the human spleen

At the end of the experiments, the spleen tissue was processed for histologic analysis and the distribution of ring- and schizont-iRBCs in the RP and perifollicular zone (PFZ) was quantified (Figure 4). The ring-iRBC tissue parasitemia was significantly higher in the RP than in the PFZ both in Giemsa-stained (2.8% vs 1.1%, P = .001, Figure 4A,B) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)–stained (3.0% vs 1.1%, P = .007, Figure 4D,E) sections. The mean (95% CI) ring-iRBC retention index defined as the ratio (“tissue parasitemia”)/(circulating parasitemia at the end of the experiment) was significantly higher in the RP (3.7; 1.9-5.4), than in the PFZ (1.4; 0.8-2.0, P = .002, Figure 4C). The mean overall retention index of ring-iRBCs in the spleen (including both zones) was 2.5. Interestingly, the retention index of ring-iRBCs in the PFZ was close to 1, suggesting that, as previously observed with artesunate-exposed iRBCs,7 the PFZ is more a transit zone than a retention/processing area for ring-iRBCs. The mean retention index of schizont-iRBCs was high (> 8) in both zones with a trend toward stronger retention in the RP. Use of PAS, which intensely stained the peculiar helix-shaped basal membrane of venous sinuses,23 allowed analysis of the distribution of ring-iRBCs in the subcompartments of the RP, specifically, the cords, the sinus lumens, and the abluminal side of the sinus walls (Figure 4F). Most (86.0% ± 6.9%) ring-iRBCs were observed in the cords, whereas 14.0% (± 6.9%) were in the sinus lumens. Significantly more ring-iRBCs were in direct contact with the PAS-stained basal membrane of venous sinuses (ie, immediately upstream of the narrow interendothelial slits), than in other subcompartments of the RP (Figure 4G). The very close proximity of knobless ring-iRBCs to the sinus basal membrane and interendothelial slits was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy (Figures 3D, 4H,I).

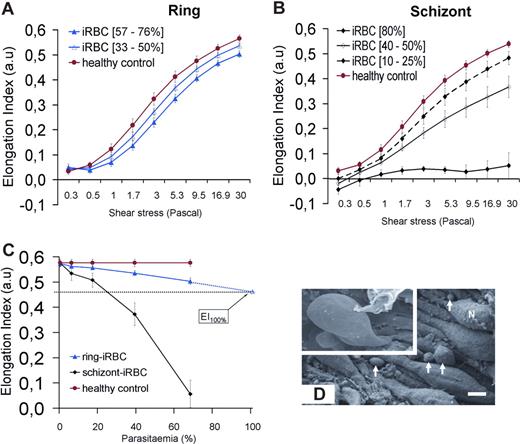

Deformability of iRBCs

The EI of ring- or schizont-iRBCs populations was measured using LORCA. To infer the deformability at the level of a single iRBC, we measured the EI of the synchronized populations at different parasitemia (3%-80% for schizonts, 4%-76% for rings, Figure 6A,B) and extrapolated to 100% parasitemia. As expected, schizont-iRBCs had a very low EI (< 0.1 at 30 Pa, 80% parasitemia) across all shear stresses (Figure 6B). At 30 Pa (similar to that encountered in the splenic sinusoids24 ), ring-iRBCs were moderately but significantly less deformable than cocultured coperfused RBCs (Figure 6A). When extrapolated to 100% iRBC population, the mean (95% CI) EI of ring-iRBC was 0.47 (0.43-0.51) versus 0.58 for control uninfected RBCs (P < .001; Figure 6C).

Deformability of iRBCs. (A,B) Elongation index (EI) of RBCs measured at different shear stresses. (C) EI of cultured ring-iRBCs and schizont-iRBCs at increasing parasitemia at 30 Pa (mean and SD of 4 independent experiments). The mean (95% CI) of the extrapolated EI of ring-iRBC at 100% parasitemia is 0.47 (0.43-0.51). (D) Scanning electron microscopy of spleen samples processed at the end of the perfusion. Endoluminal view of sinus walls showing the typical string-like aspect of endothelial cells, with their nuclei (N) protruding in the sinus lumen. Circulating cells are emerging from interendothelial slits (arrows, bar represents 3 μm). Top left quadrangle represents marked deformation of RBCs squeezing through interendothelial slits.

Deformability of iRBCs. (A,B) Elongation index (EI) of RBCs measured at different shear stresses. (C) EI of cultured ring-iRBCs and schizont-iRBCs at increasing parasitemia at 30 Pa (mean and SD of 4 independent experiments). The mean (95% CI) of the extrapolated EI of ring-iRBC at 100% parasitemia is 0.47 (0.43-0.51). (D) Scanning electron microscopy of spleen samples processed at the end of the perfusion. Endoluminal view of sinus walls showing the typical string-like aspect of endothelial cells, with their nuclei (N) protruding in the sinus lumen. Circulating cells are emerging from interendothelial slits (arrows, bar represents 3 μm). Top left quadrangle represents marked deformation of RBCs squeezing through interendothelial slits.

Discussion

The safe approaches used here provide novel, interconnected insights into the human spleen physiology and malaria pathophysiology, and raise a new paradigm whereby the ring stage population is heterogeneous, with the less deformable subset being retained in the spleen. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography showed a 2-compartment microcirculatory organization, with approximately10% of the blood input flowing through the slow compartment. A substantial proportion of ring-iRBCs was rapidly cleared by isolated-perfused human spleens. The 5.9-minute clearance half-life of the retainable ring-iRBC population fits with the removal of approximately 10% of the input at each spleen passage, consistent with their retention in the slow circulatory compartment. In keeping with that interpretation, ring-iRBCs accumulated only in the RP, along the abluminal side of sinus walls. The deformability of ring-iRBCs was moderately but significantly reduced. Those rings were tiny, lacked knobs, did not cytoadhere in vitro, and did not display any observable parasite-induced surface modification, excluding a PfEMP1-mediated retention mechanism. The overall picture indicates retention of ring-RBCs with reduced deformability upstream from the narrow interendothelial slits (ie, the microcirculatory structures of the slow compartment that stringently challenge RBC deformability11,25 ), probably reflecting an original mechanism of microorganism clearance, based on the new biophysical properties of the host cell.

A few exceptions apart,20,26 ring-iRBCs have been considered an exclusively circulating component of the total body parasite biomass during human P falciparum infection.27 Their reduced deformability has been known for decades15,28 but deemed too mild to trigger spleen retention. However, experimental and clinical observations support the hypothesis that this phenomenon does occur during the course of acute human malaria. The ex vivo spleen model filtered drug-exposed iRBCs at a rate similar to clearance rate in patients,7 and the efficient clearance of schizont-iRBCs observed here further validates this experimental setup. Importantly, a recent postmortem study reported unexplained spleen retention of knobless iRBCs, with a mean sequestration index of 2.19 in the spleen (compared with 0.63 in the liver),29 a value in line with the retention index of 2.5 determined here. We thus interpret these postmortem observations as evidence of young ring-iRBC spleen retention in these patients. Another puzzling aspect of malaria pathogenesis can be revisited in light of our findings. The parasite biomass in P falciparum–infected patients, as calculated from circulating ring-iRBCs, was 2-fold lower than calculated from plasma levels of HRP-2, a parasite protein released by mature iRBCs.27 The relative deficit in parasite biomass estimated from the circulating ring stages may be accounted for by the pool of undetected ring-iRBCs retained in the spleen. Not least, retention in the spleen of the less deformable ring-iRBCs fits with available data linking reduced RBCs' mechanical deformability and spleen clearance in patients with RBC genetic disorders. Indeed, LORCA-based measurements in spleen-intact and splenectomized thalassemic patients has provided the only approximation of the EI below which RBC retention occurs in the spleen, namely, 0.45 at 30 Pa.30 This is remarkably close to the value estimated here for ring-iRBCs (0.47 at 30 Pa).

Because the LORCA measures the EI of a population of RBCs, the EI distribution (unimodal or multimodal) of individual ring-RBCs and the extent of individual variation are unknown. Deformability studies using single-cell tools have documented the reduced deformability of ring-iRBCs compared with uninfected RBCs from the same culture15,19,28,31 and furthermore evidenced wide variations between individual cells. Multiple parasite and/or host-cell factors could contribute to ring-iRBC heterogeneously reduced deformability. The erythrocyte population is known to be heterogeneous, with circulating erythrocytes displaying different levels of maturation and senescence.32 As for the parasite, there is increasing evidence for heterogeneous expression by the individual merozoites of an array of surface molecules implicated in ligand-receptor interactions and of molecules discharged at the time of RBC merozoite invasion.18,33 Some of these interact with the erythrocyte cytoskeleton and contribute to host-cell membrane remodeling in young stages and to erythrocyte membrane stiffening after invasion.13,19 Others, such as Ring Surface Protein-2,20 predominantly associate with the surface of uninfected RBCs,18 making their direct involvement in ring-iRBC spleen retention unlikely.

What is the ultimate fate of ring-iRBCs retained in the spleen RP: multiplication or destruction? A full intrasplenic maturation process of ring-iRBCs leading to intrasplenic reinvasion could theoretically take place, although the microenvironment in the cords of the RP has been considered hostile to RBCs.34 It is possible that spleen-retained ring-iRBCs are eventually phagocytosed as innate phagocytosis of ring-iRBCs has been observed during static in vitro experiments.35 Ring-iRBC destruction in the spleen is predicted to impact on the in vivo multiplication factor per cycle, which interestingly was lower (ie, 3-16) in patients as assessed by counting circulating ring-iRBCs36,37 than predicted based on theoretical reinvasion rates (ie, 18-24).36 Such a discrepancy, usually interpreted as inefficient invasion in vivo, can also be viewed as resulting from spleen retention/clearance of a fraction of ring-iRBCs. Whatever the fate of ring-iRBCs within the spleen, their local retention reduces the parasite biomass that will sequester a few hours later in vital organs, such as the brain or the lungs. Furthermore, cryptic ring-iRBC retention in the spleen may explain why, in acute malaria, only a low proportion of the observed total RBC loss could be attributed to cumulated loss of iRBCs38 because this was based on counting circulating ring-iRBC, ignoring the spleen-retained pool of ring-iRBCs.

Because they both implicate deformability-sensing mechanisms, spleen handling/clearance of ring-iRBCs and that of uninfected RBCs are linked. A link between spleen RBC filtration and parasite multiplication rate has been speculated,15,39,40 but in humans infected with P falciparum, the iRBC population submitted to the spleen filtration process remained unidentified. Indeed, whereas mature iRBCs are known to escape spleen filtration through sequestration, circulating ring-iRBCs visualized in the peripheral blood of patients were not considered susceptible to spleen retention. Our discovery that, shortly after invasion, a subpopulation of P falciparum ring-iRBC is susceptible to spleen retention adds new strength to this link between RBC filtration and parasite multiplication. We thus infer that acquired or hereditary shift in the RBC deformability as well as acquired or hereditary variation of the threshold for RBC retention by the spleen potentially impact on the clinical outcome of P falciparum infection. Low-level spleen retention of ring-iRBCs may result in rapidly rising parasite loads leading to cerebral malaria or multiorgan failure, before anemia and splenomegaly could develop. In contrast, high-level spleen retention of both RBCs and ring-iRBCs may generate a subacute infection accompanied by intrasplenic RBCs and favor the occurrence of severe anemia, frequently associated with a palpable splenomegaly. This could explain why severe anemia and cerebral malaria rarely occur simultaneously in the same patient. This novel concept triggers a shift in malaria research fields, such as modeling of infection kinetics, estimation of parasite loads, adjuvant therapy targeting RBC deformability,41 analysis of risk factors for severe clinical forms42 (including patient age), or study of innate protection linked to hemoglobin-inherited disorders.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Olivier Helenon, Marie-Christine Prevost, François Collomp, Marie-Noëlle Ungeheuer, and Michel Huerre for efficient support

This work was supported by the Institut Pasteur Transverse Research Programs (Paris, France; PTR no. 85), by the “Fonds dédié Combattre les maladies parasitaires,” Sanofi Aventis-Ministère de L'Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche Institut Pasteur, the latter also supporting a postdoctoral fellowship (I.S.), and by a grant from Fondation pour la Recherche Medicale (Paris, France; V.B.). Research of the IMP Unit at Institut Pasteur is partly supported by the BioMalPar European Network of Excellence supported by a European grant (LSHP-CT-2004-503578) from the Priority 1 “Life Sciences, Genomics and Biotechnology for Health” in the 6th Framework Program (Paris, France). Research in the Immunophysiology and Intracellular Parasitism unit is partly supported by Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA (Paris, France).

Authorship

Contribution: I.S. and P.A.B. designed and performed research, contributed vital analytical tools, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.-M.C. performed research, contributed vital analytical tools, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; V.B. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; D.H. and S.M. analyzed data and wrote the paper; G.D. performed research and analyzed data; M.L., N.G., A.S., A.C., S.K., H.K., T.J.M., and J.-M.T. contributed vital analytical tools; I.V.-W. and C.O. performed research and contributed vital analytical tools; O.M.-P. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; and G.M. and P.H.D. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Pierre A. Buffet, Service de Parasitologie Mycologie, Groupe Hospitalier Pitié-Salpêtrière, 47 Boulevard de l'hôpital, 75651 Paris Cedex 13, France; e-mail: pabuffet@pasteur.fr.