Abstract

The clinical characteristics and prognosis remain unclear for nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ring (WR-NKTL). The aim of this study is to determine the clinical features and outcome. Ninety-one patients with WR-NKTL were reviewed. According to the Ann Arbor system, 15, 56, 12, and 8 patients had stage I, II, III, and IV. Of patients with stage I and II, 54 received combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (CMT), 13 received radiotherapy alone, and 4 patients received chemotherapy alone. All 20 patients with stage III/IV received primary chemotherapy. The disease is characterized by predominance in young males, good performance, a propensity for nodal involvement, frequent stage II through IV diseases, low frequency of elevated LDH, low-risk international prognostic index (IPI), high sensitivity to radiotherapy, and intermediate sensitivity to chemotherapy. The 5-year overall survival and progression-free survival for all patients were 65% and 51%, respectively. The age, B symptoms, stage, and IPI were important prognostic factors. CMT tended to improve the survival compared with radiotherapy alone for patients with stage I and II diseases. Both nodal involvement and distant extranodal dissemination were the primary failure patterns. WR-NKTL appears to have distinct clinical characteristics and favorable outcomes.

Introduction

Extranodal nasal-type natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma is a distinct entity according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lymphoid tissue.1,2 Although rarely diagnosed in North America and Europe, it is relatively common in Asian countries.3-13 Extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma can be further classified according to the anatomic sites of primary disease.2 Most cases of NK/T-cell lymphoma originate from the nasal cavity, hence the term nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, and tumors resembling the prototype of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma occurring in a variety of extranasal sites are referred to as nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma. Nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma constitutes a relatively well-defined entity with particular morphologic, genetic, and clinical characteristics. It is characterized by frequent angioinvasion and necrosis, a clear association with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a predilection for young males, a large proportion of stage IE disease, and a propensity for skin involvement.3-8,11 In addition, nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma is highly sensitive to radiotherapy but refractory to chemotherapy.3,6-8,14-17 As demonstrated by our previous study, radiotherapy is considered as the definitive treatment of choice for the localized disease, and overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) rates of 71% and 59%, respectively, can be achieved with primary radiotherapy.3 However, the effect of chemotherapy as primary or adjuvant therapy has not been demonstrated in several large studies.3,5-8,17-20

The primary sites of “nonnasal” nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma vary according to different definitions and categorization, but the majority occur in the upper aerodigestive tract.9,16,18,20-26 Although well recognized, the characteristics and optimal therapy of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma are largely unknown.21,22 Waldeyer ring is a circular band of lymphoid tissue consisting of the nasopharynx, tonsillar regions, base of tongue, and oropharyngeal wall. In China, it is the most common site of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the head and neck area.27-29 In contrast to primary nasal lymphomas, which are predominantly featured by NK/T-cell pathology, Waldeyer ring NHLs are mainly of the B-cell type14,28,29 ; nevertheless, most nonnasal NK/T-cell lymphomas diagnosed in the upper aerodigestive tract originate from Waldeyer ring.9,17,24,28,30 Due to its rarity, most series have reported nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ring (WR-NKTL) with other upper aerodigestive locations, or with other types of NHL of Waldeyer ring.9,17,24,27-33 To date, WR-NKTL has not been addressed or reported as a distinct disease entity.

It is well recognized that the clinical features and locations of the primary disease are of major importance in determining the biologic behavior and definition of NK-cell and T-cell lymphoma.2,13,21-23,25,26 Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that the clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and treatment outcome of WR-NKTL may differ from those of more commonly diagnosed nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma.3 Clarification of these WR-NKTL features is of significant importance, as further investigation for determining optimal therapy could be formulated. This report aims to address the clinical characteristics, pathway of tumor spread, initial response to treatment, and outcome of WR-NKTL in a large group of patients.

Methods

Patients and staging evaluation

Seven hundred eighty-five consecutive patients with newly diagnosed NHL of Waldeyer ring were retrospectively reviewed at the Cancer Hospital of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), Beijing, China, between January 1987 and December 2005. After a clinicopathologic review, 91 of these patients (11.6%) were diagnosed with WR-NKTL. Patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma were excluded from this study and were reported on previously.3 The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the CAMS and was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinicopathologic diagnosis and classification of extranodal nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma were based on the WHO classification.2 The inclusion criteria in this study were as follows: (1) primary symptoms and majority of the tumor bulk localized in the Waldeyer ring such as the nasopharynx, tonsil, base of tongue, and oropharynx; (2) pathologically confirmed diagnosis of extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma showing the features of angiocentricity, angioinvasion, zone necrosis, and polymorphism of individual cells; (3) immunohistochemical studies were positive for NK/T-cell marker including CD2+CD3ϵ+CD56+, or CD3ϵ++CD56−cytotoxic molecule+(TIA-1/granzyme B)EBV+, and negative for B-cell markers such as CD20− and/or CD79α−.

Initial clinical evaluation of patients included a complete history and physical examination; complete blood count; liver and renal function tests; serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels; chest radiograph; computed tomography of the head, neck, chest, and abdomen/pelvis; and bone marrow examination. Clinical parameters and involved lymph nodes and extranodal sites were documented. The international prognostic index (IPI) for aggressive lymphoma was calculated in all cases.34

Treatment

All patients were treated according to their presenting stage (Table 1). Radiotherapy (RT) with or without chemotherapy (CT) was the primary treatment for early stage diseases, whereas primary chemotherapy was used in patients with advanced stage diseases. For stage I and II diseases, 36 patients received chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy (CT + RT), 18 patients received radiotherapy prior to chemotherapy (RT + CT), 13 patients received radiotherapy alone, and only 4 patients received chemotherapy alone. Of the 20 patients with stage III or stage IV diseases, all patients were primarily treated with chemotherapy with or without radiation to the primary and residual tumor.

Clinical characteristics of all patients with WR-NKTL and comparison of clinical characteristics between nasopharyngeal and tonsil NK/T-cell lymphoma

| Characteristic . | All patients, n = 91, no. (%) . | Nasopharynx, n = 52, no. (%) . | Tonsil, n = 35, no. (%) . | Nasopharynx vs tonsil, P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 66 (73) | 37 (71) | 26 (74) | |

| Female | 25 (27) | 15 (29) | 9 (26) | .729 |

| Age | ||||

| Median | 37 | 37 | 42 | |

| Range | 7-79 | 9-79 | 7-69 | |

| 60 y or younger | 81 (89) | 47 (90) | 31 (89) | |

| Older than 60 y | 10 (11) | 5 (10) | 4 (11) | .785 |

| Ann Arbor stage | ||||

| I | 15 (16) | 9 (17) | 5 (14) | |

| II | 56 (62) | 34 (65) | 19 (54) | |

| III | 12 (13) | 5 (10) | 7 (20) | |

| IV | 8 (9) | 4 (8) | 4 (11) | .476 |

| Nodal involvement | ||||

| Present | 75 (82) | 39 (75) | 28 (80) | |

| Absent | 16 (18) | 13 (25) | 7 (20) | .587 |

| Involvement of adjacent organs or tissues | ||||

| Present | 54 (59) | 44 (85) | 8 (23) | |

| Absent | 37 (41) | 8 (15) | 27 (77) | .000 |

| B symptoms | 30 (33) | 23 (44) | 6 (17) | .011 |

| Elevated LDH level | 16 (18) | 10 (19) | 6 (17) | .781 |

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 | 23 (25) | 15 (29) | 7 (20) | |

| 1 | 65 (71) | 35 (67) | 27 (77) | |

| 2 | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | .609 |

| IPI | ||||

| 0 | 53 (58) | 33 (63) | 17 (49) | |

| 1 | 25 (28) | 13 (25) | 11 (31) | |

| 2 | 9 (10) | 4 (8) | 5 (14) | |

| 3 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | .707 |

| Characteristic . | All patients, n = 91, no. (%) . | Nasopharynx, n = 52, no. (%) . | Tonsil, n = 35, no. (%) . | Nasopharynx vs tonsil, P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 66 (73) | 37 (71) | 26 (74) | |

| Female | 25 (27) | 15 (29) | 9 (26) | .729 |

| Age | ||||

| Median | 37 | 37 | 42 | |

| Range | 7-79 | 9-79 | 7-69 | |

| 60 y or younger | 81 (89) | 47 (90) | 31 (89) | |

| Older than 60 y | 10 (11) | 5 (10) | 4 (11) | .785 |

| Ann Arbor stage | ||||

| I | 15 (16) | 9 (17) | 5 (14) | |

| II | 56 (62) | 34 (65) | 19 (54) | |

| III | 12 (13) | 5 (10) | 7 (20) | |

| IV | 8 (9) | 4 (8) | 4 (11) | .476 |

| Nodal involvement | ||||

| Present | 75 (82) | 39 (75) | 28 (80) | |

| Absent | 16 (18) | 13 (25) | 7 (20) | .587 |

| Involvement of adjacent organs or tissues | ||||

| Present | 54 (59) | 44 (85) | 8 (23) | |

| Absent | 37 (41) | 8 (15) | 27 (77) | .000 |

| B symptoms | 30 (33) | 23 (44) | 6 (17) | .011 |

| Elevated LDH level | 16 (18) | 10 (19) | 6 (17) | .781 |

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 | 23 (25) | 15 (29) | 7 (20) | |

| 1 | 65 (71) | 35 (67) | 27 (77) | |

| 2 | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (3) | .609 |

| IPI | ||||

| 0 | 53 (58) | 33 (63) | 17 (49) | |

| 1 | 25 (28) | 13 (25) | 11 (31) | |

| 2 | 9 (10) | 4 (8) | 5 (14) | |

| 3 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (3) | .707 |

WR-NKTL indicates nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ring; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; and IPI, international prognostic index.

Radiotherapy

A total of 77 patients in the entire cohort received radiotherapy as part of their treatment, with or without chemotherapy. Radiotherapy was delivered with a 6-MV linear accelerator in all patients. The median dose was 50 Gy at 2.0 Gy per daily fraction. The majority (66 cases, 85.7%) of patients received a radiation dose of 44 to 55 Gy.

The clinical target volume (CTV) included the Waldeyer ring, adjacent organs or structures with disease extension, and cervical lymph nodes. Two lateral opposing fields were used to encompass the Waldeyer ring and the upper neck in all except one patient. The lower neck and supraclavicular areas were treated through an anterior field. One patient was treated with intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) to cover CTV. Of the 15 patients with stage I disease, prophylactic cervical node irradiation was given in all but 1 patient who was treated with chemotherapy only and declined radiotherapy.

Chemotherapy

A total of 78 patients received chemotherapy as part of their treatment. Sixty-four patients received chemotherapy in combination with radiation, and 14 received chemotherapy alone. All except 8 patients were treated with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) or CHOP plus bleomycin (CHOP-bleo) regimen, as described previously.3,14 Seven patients received cisplatin, vincristine, bleomycin, prednisone (COBVP-16) and 1 patient was treated with cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone (COPP) due to compromised cardiopulmonary function.3,14 Patients received a median of 4 cycles of chemotherapy, with a range of 1 to 9 cycles. Of the 36 patients with stage I and II diseases who received CT + RT, 16 received 2 cycles of chemotherapy, 15 received 3 cycles of chemotherapy, and 5 received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Furthermore, 18 of those patients received 2 to 4 further cycles of combination chemotherapy after radiotherapy completion.

Follow-up and statistical analysis

Patients were evaluated weekly for response and toxicity during radiotherapy or chemotherapy. Patients were also evaluated every 3 months for the first 2 years after treatment, every 6 months for the following 3 years, and annually thereafter according to institutional policy. Complete physical examination with direct visualization of tumor bed was required at each follow-up. In addition, computed tomography of the head and neck area was routinely required.

Locoregional failure was defined as a recurrence or progression of disease in the Waldeyer ring, adjacent structures, and cervical lymph node, independent of involvement of distant lymph nodes and/or extranodal organs. OS was measured from the start of initial treatment until time of the death from any cause, or until the final follow-up. PFS was measured from the start of initial treatment until the time of first locoregional or distant progression or relapse, or until the final follow-up or any death. Both OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival curves between the different groups were compared using the log-rank test. Qualitative data comparison was performed using chi-square analysis. All analyses were performed using the SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient characteristics

Characteristics of patients and disease in regard to primary location in Waldeyer ring are listed and compared in Table 1. Subjects included 66 males and 25 females, with a male-to-female ratio of 2.6:1. Median age was 37 years, with a range from 7 to 79 years. The majority of patients were 60 years or younger. The nasopharynx and tonsil were the most frequently involved sites. Primary tumor locations were the nasopharynx (n = 52), tonsil (n = 35), base of tongue (n = 3), and oropharynx (n = 1). The most frequent presenting symptoms were odynophagia, dysphagia, and cervical lymphadenopathy. B symptoms were observed in one-third of the patients. Most patients had a good performance (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] 0-1). According to the Ann Arbor staging system, 15 patients had stage I disease, 56 had stage II, 12 had stage III, and 8 had stage IV. Seventy-eight patients (86%) were scored as low risk according to the IPI (0-1). Moreover, extension of the adjacent organs (multiple sites) within the vicinity of the primary tumor was presented in 54 (59%) of 91 patients.

Most patients (71 [78%] of 91) presented with localized disease (Ann Arbor stages I and II). Nevertheless, the majority (75 [82%] of 91) initially presented with lymph node involvement, and of those, 7 had distant extranodal spread, whereas only 15 (16%) had tumors confined to the primary location without any lymph node and extranodal organ involvement. The 1 remaining patient with stage IV had multiple cutaneous metastases without any nodal involvement. Cervical lymph nodes represented the most common cases involving lymph node sites. All patients with nodal involvement (n = 75) initially presented with positive cervical lymph nodes, and of these, 22 also had other nodal involvement sites. The distant nodal involvement sites included the axillary (n = 10), mediastinal (n = 8), para-aortic (n = 6), and inguinal regions (n = 12). Lymph nodes located in the parotid and trochlea areas were less frequently involved. Moreover, the distant extranodal sites of involvement were observed in the bone marrow, lung, and skin at diagnosis.

The major clinical features, including age, sex, stage, LDH, performance status, and IPI were similar in patients with nasopharyngeal or tonsillar NK/T-cell lymphoma (Table 1). However, patients with nasopharyngeal primary had a significantly higher probability of presenting with involvement of the adjacent organs and B symptoms. In addition, 14 (40%) of the 35 patients with tonsillar primary presented with bilateral diseases.

Response to treatment

Overall response (OR) to treatment was achieved in 88 (97%) of 91 patients, and complete response (CR) and partial response (PR) were observed in 79% and 18% of patients, respectively. Stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) were observed in 1% and 2% of patients, respectively. Table 2 describes response rates after treatment.

Response rate in patients with WR-NKTL

| . | Total, no. . | CR, no. (%) . | PR, no. (%) . | SD, no. (%) . | PD, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n = 91 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 31 | 24 (77) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT | 60 | 18 (30) | 37 (62) | 5 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 13 | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 18 | 16 (89) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 46 | 39 (85) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| CT alone | 14 | 7 (50) | 6 (43) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 91 | 72 (79) | 16 (18) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Stages I and II, n = 71 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 31 | 24 (77) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT | 40 | 9 (23) | 26 (65) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 13 | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| RT + CT | 18 | 16 (89) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 36 | 30 (83) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT alone | 4 | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 71 | 57 (80) | 11 (15) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| . | Total, no. . | CR, no. (%) . | PR, no. (%) . | SD, no. (%) . | PD, no. (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients, n = 91 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 31 | 24 (77) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT | 60 | 18 (30) | 37 (62) | 5 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 13 | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| RT + CT | 18 | 16 (89) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 46 | 39 (85) | 6 (13) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| CT alone | 14 | 7 (50) | 6 (43) | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 91 | 72 (79) | 16 (18) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Stages I and II, n = 71 | |||||

| Response after initial therapy | |||||

| RT | 31 | 24 (77) | 6 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT | 40 | 9 (23) | 26 (65) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Response after therapy | |||||

| RT alone | 13 | 10 (77) | 3 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| RT + CT | 18 | 16 (89) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| CT + RT ± CT | 36 | 30 (83) | 5 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| CT alone | 4 | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 71 | 57 (80) | 11 (15) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

WR-NKTL indicates nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of Waldeyer ring; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; RT, radiotherapy; and CT, chemotherapy.

The OR rate was 92% and 97% after chemotherapy and radiotherapy as initial treatments, respectively. However, the CR rate after initial chemotherapy was 30%, which is significantly lower than that after initial radiotherapy (77%; P = .001). Nevertheless, only 5 (8%) of 60 patients had SD or PD after initial chemotherapy.

Most patients treated with CMT achieved CR. Of the 46 patients who received CT + RT, 39 (85%) achieved CR; 11 achieved CR after initial chemotherapy; and 28 of the remaining 35 who had PR (n = 31, 67%) or SD (n = 4, 9%) after initial chemotherapy achieved CR after the completion of subsequent radiotherapy. The CR rate of the 18 patients who received RT + CT was 89%, and that of the 13 patients who received radiotherapy only was 77% (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the CR rates of patients treated with CT + RT, RT + CT, or radiotherapy alone (P = .576).

Of the 71 patients with stages I and II, CR was observed in 77% (24 of 31) after initial radiotherapy and 23% (9 of 40) after initial chemotherapy, respectively (P = .001). Of the 36 patients who received CT + RT, 8 (22%) had CR after initial chemotherapy. Among the remaining 24 patients (67%) with PR and 4 patients (11%) with SD, 22 (79%) achieved CR after completion of radiation. Therefore, CR was eventually achieved in 30 (83%) of the 36 patients treated with CT + RT, which is comparable to that of RT alone (77%) and RT + CT (89%; P = .616).

No significant differences between the response rates for patients with nasopharyngeal or tonsillar NK/T-cell lymphoma were observed (data not shown).

Survival and prognostic factors

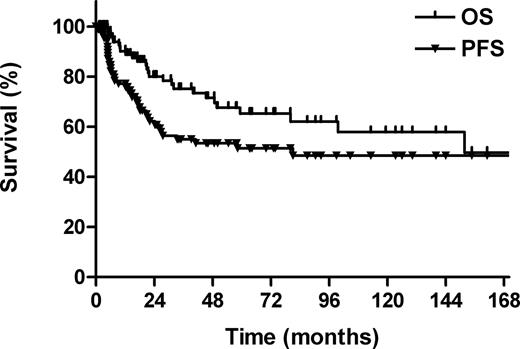

The median follow-up for all patients was 50 months (range, 1-211 months). The 5-year OS and PFS rates for all patients were 65% and 51%, respectively (Figure 1). Twenty-six patients were deceased: 22 patients died of lymphoma; 3, from intercurrent cardiopulmonary diseases; and 1, from treatment-related liver function failure.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for all patients.

Patient and disease characteristics were evaluated for prognostic significance against OS and PFS (Table 3). Age, B symptoms, stage, and IPI were found to be significant factors for OS and PFS in univariate analysis. In addition, patients with good performance showed a statistically significant superior OS and a trend toward an improved PFS.

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors with patient characteristics

| Prognostic factor . | 5-year OS . | 5-year PFS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | P . | % . | P . | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 66 | .867 | 48 | .422 |

| Female | 62 | 63 | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| 60 y or younger | 70 | .005 | 55 | .032 |

| Older than 60 y | 36 | 30 | ||

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 | 92 | .05 | 69 | .196 |

| 1 | 57 | 47 | ||

| B symptoms | ||||

| No | 74 | .003 | 58 | .009 |

| Yes | 45 | 37 | ||

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 70 | .112 | 68 | .059 |

| High | 40 | 40 | ||

| Location of primary tumor* | ||||

| Nasopharynx | 70 | .304 | 52 | .649 |

| Tonsil | 57 | 46 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| I | 93 | .004 | 69 | .011 |

| II | 71 | 58 | ||

| III/IV | 36 | 22 | ||

| IPI | ||||

| 0 | 81 | .001 | 63 | .002 |

| 1 | 56 | 49 | ||

| 2-4 | 25 | 15 | ||

| Prognostic factor . | 5-year OS . | 5-year PFS . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % . | P . | % . | P . | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 66 | .867 | 48 | .422 |

| Female | 62 | 63 | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| 60 y or younger | 70 | .005 | 55 | .032 |

| Older than 60 y | 36 | 30 | ||

| ECOG score | ||||

| 0 | 92 | .05 | 69 | .196 |

| 1 | 57 | 47 | ||

| B symptoms | ||||

| No | 74 | .003 | 58 | .009 |

| Yes | 45 | 37 | ||

| LDH | ||||

| Normal | 70 | .112 | 68 | .059 |

| High | 40 | 40 | ||

| Location of primary tumor* | ||||

| Nasopharynx | 70 | .304 | 52 | .649 |

| Tonsil | 57 | 46 | ||

| Stage | ||||

| I | 93 | .004 | 69 | .011 |

| II | 71 | 58 | ||

| III/IV | 36 | 22 | ||

| IPI | ||||

| 0 | 81 | .001 | 63 | .002 |

| 1 | 56 | 49 | ||

| 2-4 | 25 | 15 | ||

OS indicates overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; and IPI, international prognostic index.

Due to the small number of patients, 4 patients with lymphoma arising in the base of tongue and oropharynx were excluded from this analysis.

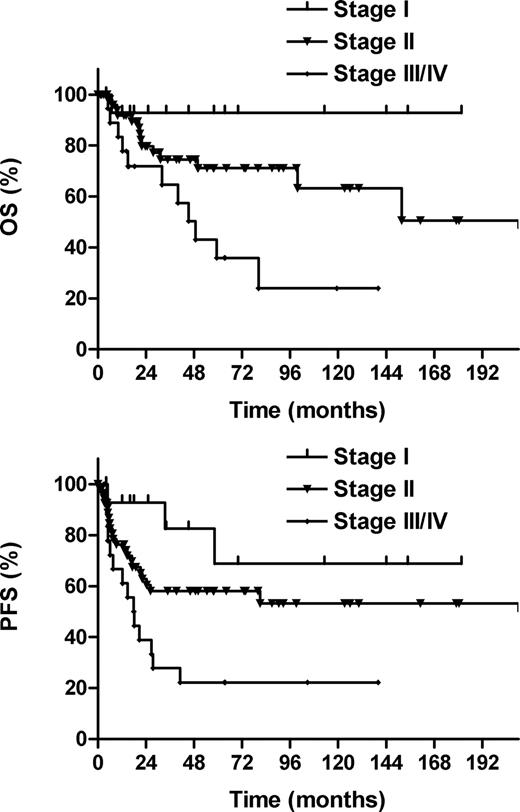

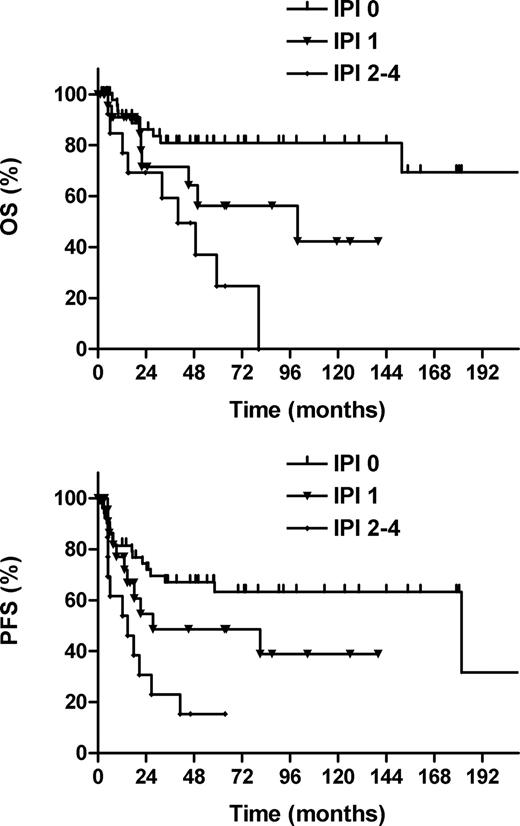

The 5-year OS and PFS rates, respectively, were 93% and 69% for Ann Arbor stage I, 71% and 58% for stage II, and 36% and 22% for stage III/IV diseases (P = .004 for OS; P = .011 for PFS; Figure 2). The IPI was a significant prognostic factor. The 5-year OS and PFS rates, respectively, were 81% and 63% for IPI 0, 56% and 49% for IPI 1, and 25% and 15% for IPI 2-4 (P = .001 for OS; P = .002 for PFS; Figure 3). No statistically significant difference in either OS or PFS was observed between diseases that arose from the nasopharynx or tonsil.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to Ann Arbor stage.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to Ann Arbor stage.

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to the international prognostic index (IPI).

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to the international prognostic index (IPI).

The prognosis of patients who achieved CR was significantly better compared with those who achieved PR or a more inferior response. The 5-year OS and PFS rates were 73% and 58%, respectively, for patients who achieved CR; no patient with PR, SD, or PD survived for more than 5 years (P = .001 for OS; P = .003 for PFS).

Outcome according to treatment modalities

Of the 71 patients with localized stage I and II diseases, the 5-year OS and PFS rates were 76% and 61%, respectively. Except for the 4 patients who received chemotherapy alone, 67 patients could be divided into the 3 subgroups according to the treatment options: radiotherapy, RT + CT, or CT + RT. With respect to sex, stage, B symptoms, LDH, performance, and IPI, patients treated with radiotherapy alone, RT + CT, or CT + RT were comparable (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). However, patients treated with radiotherapy alone were more likely to be older (> 60 years). The 5-year OS and PFS rates, respectively, were 57% and 41% after radiotherapy, 86% and 67% after RT + CT, and 75% and 65% after CT + RT (P = .199 for OS; P = .172 for PFS). The 5-year OS and PFS rates were 79% and 65%, respectively, for patients treated with CMT compared with 57% and 41%, respectively, for patients treated with radiotherapy alone (P = .092 for OS; P = .065 for PFS).

A similar analysis was performed for the 50 patients with stage II disease, the largest subgroup of the entire cohort, treated with either radiotherapy alone or sequential chemotherapy and radiotherapy (3 patients who received chemotherapy only were excluded from this analysis). The 5-year OS and PFS rates, respectively, were 75% and 65% for patients who received CMT compared with 52% and 34% for those treated with radiotherapy alone (P = .092 for OS; P = .061 for PFS).

Patterns of failure

Four patients progressed during the treatment, and 26 patients relapsed between 1 and 58 months after treatment. The majority of patients (24 [80%] of 30 patients) who relapsed did so within 2 years, and none relapsed beyond 5 years.

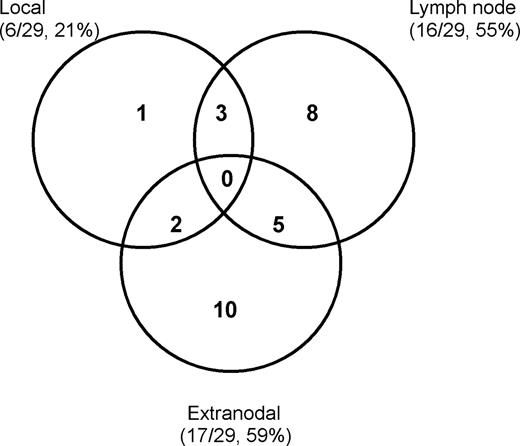

Figure 4 shows the patterns of treatment failure in 29 available patients. Both lymph node involvement and distant extranodal dissemination were the primary failure patterns. Regional and/or distant lymph node failure was observed in 16 (18%) of 91 patients, and in 8 of these, the failures were located in the cervical region. Lymph node involvement outside the head and neck was observed in the axillary, abdominal, pelvic, and inguinal areas. Seventeen (19%) of 91 patients developed a relapse or progression in the extranodal sites. The most frequent sites of extranodal failure were observed in the skin (n = 7), bone (n = 4), and lung (n = 3). Of the 6 patients (6 [7%] of 91) who experienced local relapse, all had the primary tumor in the nasopharynx. Of the 5 patients receiving radiotherapy, the failure was located in the nasal cavity with a marginal miss in the radiation field. The remaining patient developed a local relapse in the primary location after chemotherapy alone.

Locoregional failure was observed in 12 patients (12 [13%] of 91). Patients who received chemotherapy alone had a high locoregional failure rate compared with those who received radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy (42.9% [6 of 14] vs 7.8% [6 of 77]; P = .001). Twelve (15.4%) of 78 patients who received chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy and 5 (38.5%) of 13 patients who received radiotherapy alone developed extranodal failure. There was a significant difference in extranodal failure between radiotherapy alone and chemotherapy (P = .048).

The majority of patients (n = 61) received a radiation dose of 50 to 55 Gy (n = 56) or more (56-70 Gy, n = 5) to the primary tumor and cervical lymph nodes, whereas 16 patients received less than 50 Gy. For the latter patients, 13 patients received radiation dose of 40 to 48 Gy, and 3 patients received low radiation doses of 10, 14, and 25 Gy, due to the distant disease progression or stage IV disease. Fourteen patients did not receive radiotherapy (0 Gy). The overall rates of locoregional failure were 41.2% (7 of 17) for 0 to 25 Gy, 7.7% (1 of 13) for 40 to 48 Gy, and 6.6% (4 of 61) for 50 to 70 Gy (P = .001). Because of the small number of patients receiving low doses of 40 to 48 Gy or high doses of more than 55 Gy, we did not find a dose-response relationship between locoregional failure and radiation doses.

Discussion

Waldeyer ring is the most common site of the head and neck area for NHL, and accounts for 25% of all NHL cases in China.28,29 Although NHLs of the Waldeyer ring are mainly of the diffuse large B-cell type, Waldeyer ring is the most common site of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma in the upper aerodigestive tract.16,17,23,24,33 Due to its rarity, the biologic and clinical behavior of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma, as well as its optimal management strategy, remains largely unknown. In addition, the definition of nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma is complex and controversial, leading to different categorization in various institutions.21-26 To our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive evaluation that exclusively focuses on the clinical features, prognosis, and treatment outcomes of WR-NKTL patients. The following findings emerge from a total of 91 patients analyzed. Clinically, WR-NKTL has several similarities to the prototype of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, including a male predominance, young age of onset, frequent B symptoms, good performance, low-risk IPI, and sensitivity to radiotherapy. However, this disease entity also shows some different clinical features compared with the nasal variant, such as a propensity for nodal involvement, more advanced disease stages, lower frequency of elevated LDH, intermediate sensitivity to conventional chemotherapy, and favorable prognosis.3-8,17

Clinical features

In contrast to nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma, in which the submandibular lymph nodes are more often involved,3,14 the major pathway of lymph node involvement for WR-NKTL is to the cervical lymph nodes. The WR-NKTL pattern of regional nodal spread appears to be consistent with Waldeyer ring primary drainage.28 In addition, skip nodal metastasis was not observed, although NHL is usually featured by noncontiguous nodal spread. Among patients with lymphadenopathy, cervical lymph nodes were involved in all, and no patient had disease in mediastinum, axillar, or other lymph nodal groups without cervical diseases.

The majority of patients (84%) with WR-NKTL in our series presented with Ann Arbor stage II to IV disease, whereas only 16% patients had stage I disease at presentation. This differed from reports in which the frequency distribution (60%-80%) of stage I disease was predominant in patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma,3,4,6,17 but was similar to the stage distribution in other series of Waldeyer ring lymphomas in which the predominance of stage II was more frequent.28,30,33,35,36 However, the majority of patients with WR-NKTL (> 80%) presented with low-risk IPI and good performance. In contrast, patients with nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the extra-upper aerodigestive tract had more disseminated diseases and high-risk IPI in several studies.21,23,25,26,28 Furthermore, for the WR-NKTL cases in this series, the nasopharynx (57%) was frequently involved, followed by the tonsil (38%). In contrast, in all patients with NHL of Waldeyer ring, the tonsil was the most frequently involved site, accounting for 50% to 80% of all primary lesions.28,30,35-38

Primary patterns of failure were both nodal and distant extranodal spread for WR-NKTL. In contrast, the most common sites of failure were extranodal dissemination only for patients with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma or nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the extra-upper aerodigestive tract.3,5,8,22 The propensity of WR-NKTL to spread to the extranodal sites, especially the skin, observed during progression and recurrence can be explained by the homing capacity of NK/T lymphocytes.39

Response

Patients with WR-NKTL showed better response to radiotherapy than chemotherapy. A low CR rate (30%) after initial chemotherapy and a high CR rate (77%) after initial radiotherapy for WR-NKTL were consistent with previous large studies on nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma.5-7,17,18 On the other hand, the majority of patients (62%) with WR-NKTL achieved PR, and only 8% of patients had SD or PD after chemotherapy. Of the early-stage patients with PR and SD after initial chemotherapy, most of them (80%) eventually achieved CR after completion of subsequent radiotherapy. The high OR (CR + PR) rate, and lowest SD or PD rate after initial chemotherapy may reflect intermediate sensitivity to conventional chemotherapy for WR-NKTL. This particular phenomenon is in contrast to that of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma or nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the extra-upper aerodigestive tract, which are often refractory to chemotherapy. A high rate (40%) of persistent or progressive disease after initial chemotherapy was observed in our previous study of patients with early stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma.3 As expected, the chemoresistant property of nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma or nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma of the extra-upper aerodigestive tract resulted in worse survival for early-stage patients receiving chemotherapy alone or primary chemotherapy.6-8,15,17,21

Treatment

Recently, radiotherapy as primary treatment for early-stage nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma has been validated in many large retrospective studies.3-8,15,17-20 Primary radiotherapy results in a better outcome compared with chemotherapy alone or initial chemotherapy,6-8,15,17 and the addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy does not further improve survival rates for stage I and II diseases.3,5,18-20 The prognoses of patients with stage I and II diseases are relatively optimal after primary radiotherapy, with a 5-year OS rate of 30% to 86%, whereas patients with stages III and IV have an extremely poor prognosis and survival more than 5 years is rare.8,15,18-20 Due to the small number of patients, variable definitions, and different treatments, the optimal therapy for nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma or WR-NKTL has not been clearly defined.19,21 In this series, most patients received radiotherapy or CMT for early stage WR-NKTL. There was a trend toward a survival advantage with CMT for stages I and II diseases. Moreover, patients who received radiotherapy had a low rate of locoregional failure compared with those who received chemotherapy alone. In addition, patients who received chemotherapy had a low rate of systemic failure compared with those receiving radiotherapy alone. Because of the limited number of patients and retrospective analysis in this series, it is not possible to make a definite conclusion for the optimal therapy of WR-NKTL. However, considering the high CR rate and improved locoregional control with radiotherapy, and the high OR rate and reduced systemic failure with chemotherapy, WR-NKTL patients may benefit from a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

In our institution, a total dose of 50 Gy to the primary tumor was considered as radical dose for nasal and nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma,3 and additional 5 to 10 Gy was administered as a boost to the residual disease. In addition, the large radiation field was used to cover the clinical target including Waldeyer ring, neighboring organs or structures, and cervical lymph nodes for WR-NKTL patients. With the large radiation fields and high doses, we observed a very low local failure of 6.5% and low locoregional failure of 7.8% in 77 patients receiving radiotherapy. In agreement with the data from this study, several other studies have reported that the high local failure was associated with the low radiation dose and small radiation field.3,17,27,40-42

Prognosis

The prognostic factors of WR-NKTL were not addressed prior to this report. Our series demonstrated that age, B symptoms, stage, and IPI were important prognostic factors. Patients with early stage diseases had an excellent survival, with a 5-year OS rate of 93% for stage I and 71% for stage II, whereas those with stage III or IV diseases carried a worse prognosis with a 5-year OS of 36%. Previous reports have indicated that the IPI is effective in predicting the outcome in patients with aggressive NHL, nasal lymphoma, and Waldeyer ring lymphoma.3,14,28,34 We demonstrated that the IPI was of prognostic significance for WR-NKTL. Patients without any adverse factors (IPI 0) had a better outcome, with a 5-year OS of 81%, whereas those with more than one adverse factor (IPI ≥ 2) carried a worse prognosis, with an OS rate of 25%. This finding is consistent with data from previous studies, which also reported a significantly superior survival in the low-risk group for patients with nasal and nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma.3,6,8,16,31 Moreover, Lee et al analyzed 262 patients with nasal and nasal-type NK/T-cell lymphoma, identified B symptoms, elevated LDH, and regional lymph nodes as adverse prognostic factors for survival.23

In summary, WR-NKTL was associated with particular clinical features and outcome. Gene profiling or proteomics analyses and direct comparison with nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma will allow for better understanding of biologic and clinical characteristics of WR-NKTL.43

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: Y.-X.L. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; H.F. designed the research and analyzed the data; Q.-F.L., S.-N.Q., H.W., J.J., W.-H.W., Y.-P.L., Y.-W.S., S.-L.W., X.-F.L., and Z.-H.Y. made the selection of the cases and analyzed clinical data; L.J. analyzed the clinical data and wrote the paper; and X.-L.F. reviewed pathologic specimens.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ye-Xiong Li, Department of Radiation Oncology, Cancer Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) and Peking Union Medical College (PUMC), Beijing 100021, PR China; e-mail: yexiong@yahoo.com.