Abstract

Total Therapy 2 examined the clinical benefit of adding thalidomide up-front to a tandem transplant regimen for newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. When initially reported with a median follow-up of 42 months, complete response rate and event-free survival were superior among the 323 patients randomized to thalidomide, whereas overall survival was indistinguishable from that of the 345 patients treated on the control arm. With further follow-up currently at a median of 72 months, survival plots segregated 5 years after initiation of therapy in favor of thalidomide (P = .09), reaching statistical significance for the one third of patients exhibiting cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs; P = .02), a well-recognized adverse prognostic feature. The duration of complete remission was also superior in the cohort presenting with CAs such that, at 7 years from onset of complete remission, 45% remained relapse-free as opposed to 20% on the control arm (P = .05). These observations were confirmed when examined by multivariate analysis demonstrating that thalidomide reduced the hazard of death by 41% among patients with CA-positive disease (P = .008). Because two thirds of patients without CAs have remained alive at 7 years, the presently emerging separation in favor of thalidomide may eventually reach statistical significance as well.

Introduction

We have previously reported on the clinical outcomes of patients enrolled in Total Therapy 2 (TT2), a phase 3 randomized clinical trial addressing the role of thalidomide (Thal) in the up-front management of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) undergoing melphalan-based tandem transplants.1 Although overall survival (OS) on both arms of TT 2 was superior to outcomes reported for Total Therapy 1 (TT1) at the time of the original publication,2 OS was virtually identical between the 2 treatment arms of TT2. This finding was perplexing given that both the frequency of complete response (CR) and the duration of event-free survival (EFS) were superior among patients randomized to Thal. We had attributed the lack of difference in OS to a shorter postrelapse survival.

In a comparison of TT2 with TT1, we observed that patients presenting without cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs) derived the greatest benefit from TT2, which could be attributed to the introduction of posttransplant consolidation chemotherapy, whereas an improved survival among the one third of patients displaying CAs was linked to the addition of Thal in TT2.2 Improved outcomes of patients subsequently treated on the phase 2 Total Therapy 3 (TT3) protocol could be traced to both the up-front and continued use of bortezomib throughout the protocol and better protocol compliance as a result of abbreviated induction and consolidation therapies vis-à-vis TT2.3 Importantly, the presence of the t(4;14) translocation no longer was a high-risk feature in TT3.

In the era of rapid progress in MM therapy as a consequence of access to an increasing armamentarium of novel agents, much emphasis has been placed on increasing the frequency of CR as an early surrogate endpoint for extended survival. Indeed, CR rates have been raised to levels of 30% with novel agent combinations and are thus approaching results previously reported only for high-dose melphalan-based transplant trials.4 We and others have drawn attention recently to a need for reevaluating CR as a trial endpoint in MM therapy, as we had reported on CR-independent OS among patients presenting with MM-preceding monoclonal gammopathy of uncertain significance (MGUS) or smoldering multiple myeloma conditions5 as well as those with MGUS-like gene expression profiling (GEP) signatures.6 On the other hand, however, we noted that attaining CR status was crucial for patients presenting with GEP-defined high-risk features.7 Similarly, sustenance of CR for at least 3 years from treatment initiation was especially important for patients presenting with high-risk disease.8 Finally, completion of intended therapies assured superior outcomes in patients presenting with CAs or GEP-defined high-risk.9

The Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome had reported that the use of Thal as maintenance after transplant was associated with both superior EFS and OS.10 The authors stressed that the benefit of Thal was linked to a conversion of response status from a lower level to very good partial response or better. The investigators had advanced a similar argument when reporting follow-up data of their randomized trial comparing tandem with single transplants, noting that the benefit from a second transplant was limited to patients not yet in CR or very good partial response after the first high-dose intervention.11

In reviewing long-term outcome results, we have been impressed with the St Jude group's Total Therapy experience in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, noting that, in this much more proliferative malignancy vis-à-vis MM, the appearance of a survival plateau was not apparent until approximately 4 years from initiation of therapy for all successive studies 1 to 15 over a time span from 1962 to 2005.12 In light of these results and a median overall survival in TT2 in excess of 8 years, a reexamination of long-term outcomes appeared in order especially because, as in leukemia and lymphoma, myeloma, too, comprises distinct genetically defined entities.13,14 We therefore investigated the long-term outcomes of all 668 patients enrolled in TT2, with a median follow-up currently of 72 months as opposed to the 42 months in our original report. We now find a survival advantage in the group of patients treated on the experimental Thal arm, emerging 5 years after enrollment, that was significant for the one third of patients presenting with the high-risk CA-type myeloma. In addition to short-term reporting to understand rapid treatment failures, our observations therefore stress the need as well for long-term follow-up, to reveal potential benefits of the introduction of novel therapies that might not be apparent in early analyses. The integration of the 2 has far-reaching consequences for further improving myeloma outcomes through appropriately adjusted trial designs

Methods

The details of the TT2 program have been previously reported. Briefly, eligible newly diagnosed patients were randomly assigned to a control arm or an experimental arm that included Thal during all phases of treatment. Treatment included 4 induction cycles, followed by melphalan-based tandem autotransplantation, 4 cycles of chemotherapy consolidation, and maintenance therapy with interferon-alpha-2b to which dexamethasone was added in pulsed fashion during the first year.1 All 668 patients signed an informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Food and Drug Administration and National Cancer Institute guidelines. These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

The median follow-up is 72 months; 273 patients have died (138 because of disease progression, 49 because of treatment-related toxicity, 71 because of indeterminate causes, and 15 because of indeterminate nonprogressive disease) and 384 suffered an event (258 relapse or progression, 126 deaths without relapse or progression). Thal was discontinued in 43% of patients after a median of 30 months. Reasons for drug discontinuation included disease relapse or progression in 199 patients after a median of 50 months, toxicity mainly of the peripheral neuropathy type in 89 patients after a median of 31 months, and either patient or physician preference in the remaining 35 patients after a median of 30 months.

Data are reported as of March 2008. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate EFS and OS.15 EFS was defined from date of registration to the occurrence of death from any cause, disease progression or relapse, or censored at the date of last contact. OS was defined from date of registration to the date of death from any cause or censored at the date of last contact. Duration of complete response was defined from the earliest date of complete response to the date of death from any cause, disease progression or relapse, or was censored at the date of last contact. Cumulative incidence of response was determined using off-study or death events as competing risks.16 The Cox regression method was used to examine multivariate prognostic factor models for OS, EFS, time to complete response, and duration of complete response.17

Results

Overall outcomes

The clinical outcome data are depicted for all patients in Figure 1, revealing median OS and EFS durations of 8 years and 5.1 years, respectively; at 8 years, 50% remain alive and 33% event-free (Figure 1A). The cumulative frequencies of patients achieving CR and near-complete response (n-CR) status are portrayed in Figure 1B, reaching levels at 3 years of 50% and 72%, respectively. At 8 years from onset of response, 49% of those achieving CR and 42% of patients qualifying for n-CR status remain relapse-free (Figure 1C).

Overall clinical outcomes on Total Therapy 2. (A) Overall and event-free survival. At 8 years, 50% of patients are alive and 33% have remained event-free. (B) Cumulative complete and near-complete response. At 3 years, 72% have achieved near-complete response (n-CR), including 50% who achieved complete response (CR). (C) Duration of CR or n-CR. Of those achieving response, 8-year estimates of CR and n-CR are 49% and 42%, respectively.

Overall clinical outcomes on Total Therapy 2. (A) Overall and event-free survival. At 8 years, 50% of patients are alive and 33% have remained event-free. (B) Cumulative complete and near-complete response. At 3 years, 72% have achieved near-complete response (n-CR), including 50% who achieved complete response (CR). (C) Duration of CR or n-CR. Of those achieving response, 8-year estimates of CR and n-CR are 49% and 42%, respectively.

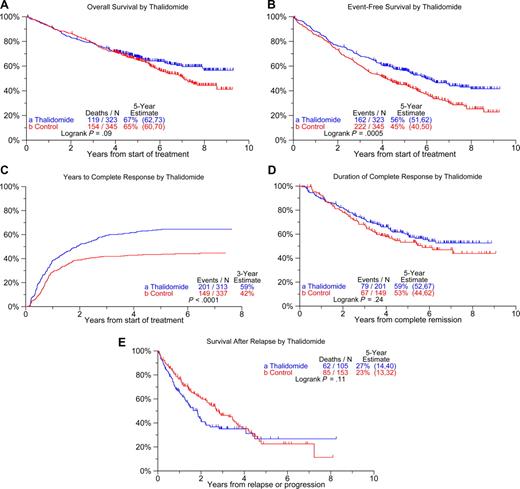

Figure 2 shows Kaplan-Meier plots for the 2 treatment arms: OS plots segregate at 5 years with 8-year estimates of 57% among the 323 patients randomized to Thal compared with 44% for the 345 on the control arm (Figure 2A, P = .09). EFS was superior in patients on the experimental arm with median durations of 6.0 years versus 4.1 years (Figure 2B; P = .001). Although CR status was attained in a higher proportion of patients randomized to Thal relative to the control arm (5-year estimates: 64% vs 43%; Figure 2C; P < .001), CR duration was similar in the 2 arms (Figure 2D). Postrelapse survival tended to be shorter among patients initially randomized to Thal than in those treated on the control arm (Figure 2E; P = .11).

Clinical outcomes according to treatment arms. (A) Overall survival. A trend toward superior survival of patients randomized to thalidomide emerged 5 years after enrollment on study (P = .09). (B) Event-free survival. Patients randomized to thalidomide have superior event-free survival compared with those treated on the control arm (P = .001). (C) Cumulative CR rates. The frequency of CR is significantly higher on the thalidomide versus control arm (P < .001). (D) Duration of CR from its onset. Durations of complete remission are similar in the 2 study arms. (E) Postrelapse survival. Postrelapse survival tended to be shorter among patients who were initially treated on the thalidomide arm.

Clinical outcomes according to treatment arms. (A) Overall survival. A trend toward superior survival of patients randomized to thalidomide emerged 5 years after enrollment on study (P = .09). (B) Event-free survival. Patients randomized to thalidomide have superior event-free survival compared with those treated on the control arm (P = .001). (C) Cumulative CR rates. The frequency of CR is significantly higher on the thalidomide versus control arm (P < .001). (D) Duration of CR from its onset. Durations of complete remission are similar in the 2 study arms. (E) Postrelapse survival. Postrelapse survival tended to be shorter among patients who were initially treated on the thalidomide arm.

Prognostic factors

We next examined clinical outcomes by treatment arm in relationship to the presence of CA, a cardinal adverse prognostic feature. OS was superior on the Thal arm only among patients with CA (Figure 3A; P = .02). When examined in the context of GEP data, available in 351 patients, Thal's benefit to those with CA was readily apparent among the 87% with GEP-defined low-risk disease (Figure 3A; P = .01). In the case of EFS, patients randomized to Thal fared better than the control group whether or not CA was present (Figure 3B). Segregation of OS plots became evident 2 to 3 years after treatment initiation in patients presenting with CAs but has only begun to emerge at 7 years in the absence of CAs. The cumulative frequency of CR was significantly higher in the Thal versus non-Thal cohort, regardless of CA status (Figure 3C), whereas CR duration was superior with Thal only in the presence of CA (Figure 3D; P = .05). In the absence of CA, postrelapse survival was superior among patients initially randomized to the control arm (P = .04), whereas such difference was not observed when patients presented with CA (Figure 3E; P = .99).

Clinical outcomes according to treatment arms and the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities. (A) Overall survival in all patients (left panel) and in subset with gene expression profiling (GEP)–defined low-risk myeloma. Survival is superior on the thalidomide arm only in patients presenting with cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs; P = .02), which also pertained to the subset with low-risk disease defined by GEP (P = .01). (B) Event-free survival. Event-free survival is superior in patients randomized to thalidomide versus the control arm, regardless of the presence of CA. (C) Cumulative CR rates. The proportion of patients achieving CR status was higher among those randomized to thalidomide in comparison to patients treated on the control arm, regardless of CA. (D) Duration of CR from its onset. The duration of CR is superior among patients randomized to thalidomide only among those presenting with CA (P = .05). (E) Postrelapse survival. Postrelapse survival was superior among patients initially randomized to the control arm in the absence of CA at baseline (P = .04), whereas such difference was not observed in case patients presented with CA (P = .99).

Clinical outcomes according to treatment arms and the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities. (A) Overall survival in all patients (left panel) and in subset with gene expression profiling (GEP)–defined low-risk myeloma. Survival is superior on the thalidomide arm only in patients presenting with cytogenetic abnormalities (CAs; P = .02), which also pertained to the subset with low-risk disease defined by GEP (P = .01). (B) Event-free survival. Event-free survival is superior in patients randomized to thalidomide versus the control arm, regardless of the presence of CA. (C) Cumulative CR rates. The proportion of patients achieving CR status was higher among those randomized to thalidomide in comparison to patients treated on the control arm, regardless of CA. (D) Duration of CR from its onset. The duration of CR is superior among patients randomized to thalidomide only among those presenting with CA (P = .05). (E) Postrelapse survival. Postrelapse survival was superior among patients initially randomized to the control arm in the absence of CA at baseline (P = .04), whereas such difference was not observed in case patients presented with CA (P = .99).

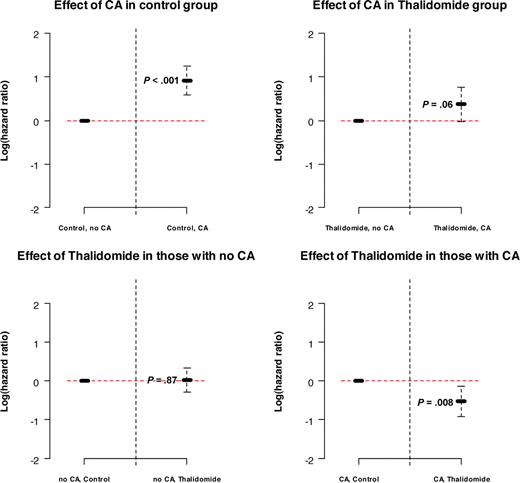

Next we applied multivariate analyses to determine whether randomization to Thal affected the 4 clinical outcome endpoints after adjustment for standard prognostic factors (Table 1). OS was dominantly adversely affected by the presence of CA, elevated levels of β2-microglobulin and lactic dehydrogenase, as well as by hypoalbuminemia. Importantly, when examined in the context of variable interactions, a significant interaction was found between Thal and CA. Thus, although randomization to Thal was not significant in patients who presented without CA, randomization to Thal was recognized as an independent favorable variable among patients presenting with CA (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.59; P = .008; Figure 4), which still pertained when examined in the subset of 351 patients with available GEP data (HR = 0.40; P = .001; data not shown). In the case of EFS, IgA isotype was an additional adverse feature. CR was higher among patients randomized to Thal, in case of λ light chain isotype and in the presence of elevated C-reactive protein levels. CR duration was shorter in the presence of CA and β2-microglobulin elevation.

Multivariate analyses of standard prognostic variables associated with clinical outcomes

| Variable . | Overall survival . | Event-free survival . | Complete response . | Duration of complete response . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | |

| Randomization to thalidomide | 309/634 (49%) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) | 0.872 | 312/642 (49%) | 0.67 (0.55, 0.83) | <.001 | 303/618 (49%) | 1.59 (1.28, 1.97) | <.001 | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 188/634 (30%) | 2.51 (1.80, 3.49) | <.001 | 194/642 (30%) | 1.64 (1.32, 2.03) | <.001 | — | — | — | 82/340 (24%) | 1.90 (1.35, 2.69) | <.001 |

| Thalidomide and presence of CA | 89/634 (14%) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.95) | 0.032 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | — | — | — | 117/642 (18%) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | 0.023 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| β2-Microglobulin > 5.5 mg/L | 115/634 (18%) | 1.61 (1.21, 2.16) | 0.001 | 116/642 (18%) | 1.47 (1.13, 1.90) | 0.004 | — | — | — | 57/340 (17%) | 1.89 (1.30, 2.75) | <.001 |

| Lambda light chain | — | — | — | — | — | — | 233/618 (38%) | 1.27 (1.02, 1.58) | 0.035 | — | — | — |

| IgA isotype | — | — | — | 154/642 (24%) | 1.34 (1.06, 1.70) | 0.014 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lactic dehydrogenase ≥ 190 U/L | 197/634 (31%) | 1.52 (1.16, 1.98) | 0.002 | 198/642 (31%) | 1.42 (1.13, 1.77) | 0.002 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| C-reactive protein ≥ 8.0 mg/L | — | — | — | — | — | — | 249/618 (40%) | 1.35 (1.08, 1.68) | 0.007 | — | — | — |

| Variable . | Overall survival . | Event-free survival . | Complete response . | Duration of complete response . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | n/N (%) . | HR (95% CI) . | P* . | |

| Randomization to thalidomide | 309/634 (49%) | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) | 0.872 | 312/642 (49%) | 0.67 (0.55, 0.83) | <.001 | 303/618 (49%) | 1.59 (1.28, 1.97) | <.001 | — | — | — |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities | 188/634 (30%) | 2.51 (1.80, 3.49) | <.001 | 194/642 (30%) | 1.64 (1.32, 2.03) | <.001 | — | — | — | 82/340 (24%) | 1.90 (1.35, 2.69) | <.001 |

| Thalidomide and presence of CA | 89/634 (14%) | 0.58 (0.35, 0.95) | 0.032 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Albumin < 3.5 g/dL | — | — | — | 117/642 (18%) | 1.35 (1.04, 1.75) | 0.023 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| β2-Microglobulin > 5.5 mg/L | 115/634 (18%) | 1.61 (1.21, 2.16) | 0.001 | 116/642 (18%) | 1.47 (1.13, 1.90) | 0.004 | — | — | — | 57/340 (17%) | 1.89 (1.30, 2.75) | <.001 |

| Lambda light chain | — | — | — | — | — | — | 233/618 (38%) | 1.27 (1.02, 1.58) | 0.035 | — | — | — |

| IgA isotype | — | — | — | 154/642 (24%) | 1.34 (1.06, 1.70) | 0.014 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lactic dehydrogenase ≥ 190 U/L | 197/634 (31%) | 1.52 (1.16, 1.98) | 0.002 | 198/642 (31%) | 1.42 (1.13, 1.77) | 0.002 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| C-reactive protein ≥ 8.0 mg/L | — | — | — | — | — | — | 249/618 (40%) | 1.35 (1.08, 1.68) | 0.007 | — | — | — |

The significant interaction between thalidomide and cytogenetic abnormalities (CA; HR = 0.58; P = .032) means that the effect of thalidomide is different for patients with and without CA. In patients without CA, thalidomide has no effect on survival (HR = 1.03; P = .87). In patients with CA, the effect of thalidomide is a significant reduction in the risk of death of 41% (HR = 0.59; P = .008), which was also found to be true in an analysis done in the subset of patients who had baseline gene array data available (HR = 0.40; P = .001; data not shown).

HR indicates hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; and —, not applicable.

P from Wald χ 2 test in Cox regression. Multivariate results not statistically significant at the .05 level. All univariate P values reported regardless of significance. Multivariate model uses stepwise selection with entry level 0.1 and variable remains if meets the 0.05 level. A multivariate P value greater than .05 indicates variable forced into model with significant variables chosen using stepwise selection.

Log (hazard ratio) values in overall survival model depicting the role of interaction between cytogenetic abnormalities and thalidomide. The presence of CA has a significant adverse effect on OS in control group (P < .001), whereas the adverse effect in the thalidomide group is not significant (P = .06). Thalidomide has no effect on OS in patients with no CA (P = .87) but has a significant beneficial effect on OS in patients with CA (P = .008).

Log (hazard ratio) values in overall survival model depicting the role of interaction between cytogenetic abnormalities and thalidomide. The presence of CA has a significant adverse effect on OS in control group (P < .001), whereas the adverse effect in the thalidomide group is not significant (P = .06). Thalidomide has no effect on OS in patients with no CA (P = .87) but has a significant beneficial effect on OS in patients with CA (P = .008).

Effect of duration and cumulative total dose of thalidomide administered

Reiterative landmark analyses were performed to investigate whether there was an impact on clinical outcomes of the duration of Thal administration and of the cumulative dose applied. Neither was found to affect survival or the other 3 end points among patients randomized to the Thal arm (data not shown).

Implications of randomization to thalidomide on MRI-defined focal lesions and on myelodysplasia-associated cytogenetic abnormalities

Because Thal targets not only MM cells but also the bone marrow micro-environment,18 the time course to resolution of MRI focal lesions (MRI-CR) present at baseline was also examined. In patients randomized to Thal, there was a trend for onset of MRI-CR to occur earlier (median, 2.2 years vs 2.8 years; P = .13) and the proportion of patients attaining this status to be higher among patients initially randomized to Thal.

Because Thal and especially lenalidomide have been reported to exhibit clinical activity in patients diagnosed with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS),19,20 we examined whether there were differences in the development of MDS-associated cytogenetic abnormalities (MDS-CA) between the 2 study arms.21 The 5-year cumulative frequency of MDS-CA was identical at 4% in both arms, indicating that Thal provided no protective effect against the development of therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (t-MDS).

Discussion

In our original report on TT2, we attributed the absence of a survival benefit on the experimental arm to Thal's use as salvage therapy in patients relapsing on the control arm that resulted in their longer postrelapse survival, compensating for their shorter initial EFS.1 With longer follow-up, we now observe that, in addition to increasing the frequency of CR and extending EFS as originally reported, Thal also provided a survival benefit that is currently limited to those presenting with CAs. Such patients also enjoyed longer CR duration. Postrelapse survival was impacted adversely by initial Thal randomization only in subjects not exhibiting CA-type MM. Although MM and even its more common precursor condition, MGUS, exhibit genetic abnormalities virtually universally when examined by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis22 and GEP, the detection of CAs not only depends on MM cell division in vitro but represents a surrogate for bone marrow stroma-independent proliferation.23 Given the purported mechanisms of Thal's antitumor activity that include antiangiogenesis, antiadhesive, and stroma-myeloma-disruptive effects, we were surprised to note its benefiting patients with CA-positive MM, an observation that was upheld on multivariate analyses whether or not GEP data were included.

Equally important was the inability of tying Thal's survival benefit to dose or duration of therapy, suggesting that perhaps even short exposure to this immunomodulating agent may have far-reaching consequences as observed in this update. This finding has several important implications. First, because there are significant toxicities associated with long-term use of Thal, it is possible that more limited exposure could be entertained with similar beneficial outcomes. This concept could be tested in a prospective randomized clinical trial. Second, serial GEP analyses after single-agent exposure to dexamethasone and Thal as part of this trial may be of interest. Consenting patients had received, according to their randomization, either Thal 400 mg/d for 2 days or, in case of assignment to the control arm, dexamethasone 40 mg/d for 2 days. In a comparison of 48-hour postintervention and baseline samples, we observed distinctly different sets of genes that were up- or down-regulated by these 2 agents.24 Moreover, such 48-hour changes also affected EFS and OS.25 Although the number of cases in this pilot study was too small to examine the effects of short-term GEP changes within the CA-positive and -negative groups, such studies may prove invaluable in confirming the relationship between CA and the beneficial effects of Thal.

As MM comprises a spectrum of distinct molecular entities with low- and high-risk subtypes being represented in each, clinical trials of new agents in phase 2 or 3 settings have to be powered sufficiently for therapeutic benefits of new agents to be detected in all diverse forms of MM. The availability of GEP data in only 351 patients (test became available halfway through the study) of a total of 668 enrolled into this trial precluded an exhaustive analysis of Thal's benefit in the context of molecular subgroups14 and GEP risk scores.13 The superior performance on the Thal arm of patients harboring CAs still applied when GEP information was included, supporting a yet unexplained differential benefit of Thal toward the CA subgroup. Although the proportion of patients attaining CR status was significantly higher on the Thal arm whether or not CAs were present, CR duration was extended by Thal only in the CA subgroup. Importantly, postrelapse survival was only shorter for those randomized to Thal when CA was absent at baseline.

Although the Intergroupe Francophone du Myelome reported that a survival benefit of patients receiving Thal maintenance was limited to those experiencing a response upgrade after transplantation,10 we observed extensions of survival and CR duration with Thal only in the CA subgroup despite higher CR rates also in patients lacking CA. Although highly correlated with other adverse prognostic parameters, including GEP-defined proliferation designation and high-risk subgroups, the presence of CAs remained an independent adverse baseline variable in a comparison of TT3 and TT2 outcomes.3 Studies are therefore warranted to determine whether a CA-unique MM-cell expression signature can be identified.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (P01 grant CA55819), Bethesda, MD (B.B., F.v.R., J.E., J.D.S., J.C.).

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: B.B., M.P.-R., F.v.R., J.E., J.D.S., J.Z., and S.B. conceptualized work and wrote the manuscript; B.B., M.P.-R., F.v.R., E.A., K.H., Y.A., S.W., G.T., and M.Z. enrolled and treated patients; N.P. collected data; and J.H. and J.C. analyzed data.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bart Barlogie, Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham, No. 816, Little Rock, AR 72205; e-mail: barlogiebart@uams.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal