Abstract

Erythropoiesis strictly depends on signal transduction through the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR)–Janus kinase 2 (Jak2)–signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (Stat5) axis, regulating proliferation, differentiation, and survival. The exact role of the transcription factor Stat5 in erythropoiesis remained puzzling, however, since the first Stat5-deficient mice carried a hypomorphic Stat5 allele, impeding full phenotypical analysis. Using mice completely lacking Stat5—displaying early lethality—we demonstrate that these animals suffer from microcytic anemia due to reduced expression of the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 followed by enhanced apoptosis. Moreover, transferrin receptor-1 (TfR-1) cell surface levels on erythroid cells were decreased more than 2-fold on erythroid cells of Stat5−/− animals. This reduction could be attributed to reduced transcription of TfR-1 mRNA and iron regulatory protein 2 (IRP-2), the major translational regulator of TfR-1 mRNA stability in erythroid cells. Both genes were demonstrated to be direct transcriptional targets of Stat5. This establishes an unexpected mechanistic link between EpoR/Jak/Stat signaling and iron metabolism, processes absolutely essential for erythropoiesis and life.

Introduction

Erythroid cell formation needs to be tightly regulated to maintain proper tissue oxygenation. Although about 1011 red cells are produced every day in humans, total red cell numbers are kept within a narrow range in bone marrow, spleen, and fetal liver. While early erythroid lineage commitment is controlled by numerous transcription factors and their binding partners (like GATA-1, FOG-1, and EKLF),1 later stage differentiation from erythroblasts to mature erythrocytes is strictly regulated by erythropoietin (Epo).2

Epo induces dimerization of erythropoietin receptor (EpoR), which results in juxtaposition and activation of the receptor-associated Janus kinase 2 (Jak2). Jak2 subsequently phosphorylates several tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic tail of EpoR, which in turn acts as docking sites for signaling molecules such as PI3-K3 , MAPK,4 PKC,5 and PLC-γ.6 A central pathway of EpoR signaling is the activation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (Stat5).7,8 Upon EpoR phosphorylation, Stat5 molecules are tyrosine-phosphorylated by Jak2 and translocate to the nucleus. This leads to activation of Stat5 target genes such as Pim-1, c-myc, Bcl-xL, D-type cyclins, oncostatin M, and SOCS members that play important roles in differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, and other processes.9–15

The importance of Epo signaling is evidenced by the phenotypes of Epo−/−, EpoR−/−, and Jak2−/− mice, which die in utero at embryonic day (E) 13.5 due to defects in erythropoiesis. Fetal livers of Jak2−/− animals completely lack BFU-E (burst forming unit–erythroid) and CFU-E (colony forming unit–erythroid) progenitors. In line with this, Epo- and EpoR-deficient embryos also fail to develop mature erythroid cells in vivo.16–18 Interestingly, mice expressing a truncated form of EpoR (EpoRH), which solely activates Stat5 and lacks all critical phosphotyrosine sites required to activate other signaling pathways, exhibited no strong erythroid phenotype,15,19 suggesting Stat5 as a critical component of the EpoR signaling pathway. Unexpectedly, however, mice expressing an EpoR mutant additionally lacking the binding site for Stat5 (EpoRHM) displayed no overt erythroid phenotype except under stress conditions.15,19 Moreover, the mice initially reported to be deficient for Stat5a and Stat5b were viable and had a surprisingly mild erythroid phenotype.7,20,21 Although showing fetal anemia, adult animals only displayed mild defects in recovery from phenylhydrazine-induced erythrolytic stress. This was explained by increased apoptosis in early erythroid progenitors, due to lack of Stat5-induced expression of the antiapoptotic gene Bcl-xL.21 Later, however, these initial Stat5 knockout animals—now referred to as Stat5ΔN/ΔN—were found to express a N-terminally truncated protein able to bind DNA and to activate a subset of Stat5 target genes.14,22–25 In contrast to Stat5ΔN/ΔN, the recently described bona fide Stat5a/b null knockout mice (referred to as Stat5−/−)8 die during gestation or at latest (< 2%) shortly after birth. Complete ablation of Stat5 resulted in severe defects in generation of all lymphoid lineages.23,24,26 However, an accurate analysis of the erythroid compartment from these mice is still missing.

Maturing erythroid progenitors depend on large amounts of bioavailable iron (humans require 20 mg iron complexed to transferrin per day) to enable efficient heme synthesis. Cellular uptake of iron-loaded transferrin is mediated by transferrin receptor-1 (TfR-1; also called CD71),27 followed by receptor internalization. Accordingly, maturing erythroid cells express high levels of TfR-1. However, as excess iron would lead to oxidative damage, expression of proteins involved in iron uptake, storage, and utilization is tightly controlled. In case of TfR-1, this occurs primarily at the level of TfR-1 mRNA stability28 and to a lesser extent at the transcriptional level.29 At low-iron conditions, trans-acting iron regulatory proteins (IRP1 + 2) bind to conserved hairpin structures (iron-responsive elements [IREs]) in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of TfR-1 mRNA, which selectively stabilizes this mRNA and ensures proper TfR-1 cell-surface expression and iron uptake.30–32 Upon iron excess, IRP-1 is converted to a cytosolic aconitase catalyzing isomerization of citrate to isocitrate,33 while IRP-2 is degraded by the proteasome.34 Thus, both proteins no longer bind to IREs, resulting in strongly reduced TfR-1 mRNA stability, which leads to reduced TfR-1 cell-surface expression and iron uptake.35–37 Recently generated knockout mouse models for IRP-1 and IRP-2 suggested IRP-2 as the master regulator of IRE-regulated mRNAs, as ablation of IRP-2 led to a decrease in TfR-1 expression and microcytic anemia, while IRP-1 knockout animals had no overt phenotype.38,39

Here we show that Stat5−/− embryos suffer from severe microcytic anemia, a disease mostly associated with iron deficiency and characterized by small-sized red blood cells. In Stat5-deficient animals this anemia had 2 causes: first, fetal livers were much smaller in knockout embryos due to a strong increase of apoptosis in the erythron. We demonstrate that the antiapoptotic proteins Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL were largely absent in Stat5−/− cells, but ectopic expression of Mcl-1 complemented the survival defect of Stat5−/− erythroid cells. Second and more important, we demonstrate for the first time a direct link between Stat5 and iron metabolism. In the absence of Stat5, IRP-2 expression was strongly decreased, resulting in more than 2-fold lower cell-surface expression of TfR-1 and thus strongly reduced iron uptake in erythroid cells. Together, the high levels of apoptosis and impaired iron uptake caused severe microcytic anemia and probably contributed to the death of Stat5−/− embryos.

Methods

Cell culture and retroviral infections

Stat5+/− mice8 were maintained under pathogen-free conditions and bred on a mixed background (C57Bl/6 × Sv129F1) to obtain Stat5−/− embryos. For the determination of blood indices, heparinized blood was measured in a Vet ABC Blood Counter (Scil Animal Care, Viernheim, Germany). Serum Epo levels were determined using a Quantikine mouse erythropoietin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol, measured on a Victor3 V 1420 multilabel counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). All animal experiments described in our manuscript were performed in accordance with Austrian and European laws and under approval of the ethical and animal protection committees of the Veterinary University of Vienna.

Fetal livers of E13.5 mouse embryos (Stat5−/− and wild type [wt]) were resuspended in serum-free medium (StemPro-34; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In brief, for self-renewal,40 cells were seeded into medium containing 2 U/mL human recombinant Epo (Erypo; Cilag AG, Sulzbach, Germany), murine recombinant stem cell factor (SCF; 100 ng/mL; R&D Systems), 10−6 M dexamethasone (Dex; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1; 40 ng/mL; Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting erythroblast cultures were expanded by daily partial medium changes and addition of fresh factors, keeping cell densities between 2 and 4 × 106 cells/mL. Proliferation kinetics and size distribution of cell populations were monitored daily in an electronic cell counter (Casy-1; Innovatis AG, Reutlingen, Germany).40 For retroviral infections, fetal liver erythroblasts were cocultured for 72 hours with retrovirus-producing fibroblast cell lines selected for high virus production.14 Infection efficiency was 75% to 95% as measured by flow cytometry for green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression. Cytospun cells were fixed in methanol, embedded in Entellan (Sigma-Aldrich), and stained with either Benzidine, May-Gruenwald Giemsa, or Wright-Giemsa solutions according to manufacturer's protocols (all Sigma-Aldrich). Photomicrographs were taken using an Axiovert 10 microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with a 63× oil-immersion lens (numeric aperture 44-07-61), a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5, and Axiovision LE software, version 4.5. Images were processed with Adobe Photoship CS2 and are presented at ×630 magnification.

Flow cytometry

Cultured erythroblasts or single-cell suspensions of freshly isolated fetal livers were stained with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies (all from BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) against Ter-119 (PE-conjugated) and TfR-1 (biotinylated) for in vivo erythroid development analyses. Annexin V (APC-conjugated) staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. For in vivo proliferation assays, pregnant mice were injected with 80 mg BrdU per kilogram of body mass. After 1 hour, embryos were isolated, and fetal liver cells were fixed and stained with anti-BrdU–FITC plus Ter-119–PE following the manufacturer's protocol (BrdU flow kit; BD Biosciences). Samples were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Where indicated, Ter-119+ cells were isolated by magnetic cell sorting using Auto-MACS (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

Western blot analysis

The following antibodies were used for Western blotting: anti–mouse ERK1/2, anti–horse ferritin H, anti–mouse actin (all from Sigma-Aldrich), anti–mouse TfR-1 (BioSource, Camarillo, CA), anti–mouse Bcl-xL, anti–mouse PCNA, anti–mouse Stat5 (all from BD Transduction Laboratories, Erembodegem, Belgium), anti–mouse Mcl-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti–mouse eIF4E, anti–mouse eIF2-alpha, pSer-eIF2-alpha (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti–rat IRP-1,41 and anti IRP-2.39

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation was performed as in LeBaron et al.42 A total of 2 × 107 primary erythroblasts were stimulated with 10 U Epo/mL for 30 minutes. Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 30 minutes. DNA was sonicated using a Bandelin Sonoplus GM70 sonicator (cycle count, 30%; power, 45%; 6 × 30 seconds; Bandelin Electronic, Berlin, Germany). DNA fragments were recovered using anti–mouse Stat5ab (C20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti–mouse Stat5 (N20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Recovered DNA fragments were directly used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). RNA integrity was checked with the Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). A total of 2.5 μg RNA was reverse transcribed using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed on an Eppendorf Master-cycler RealPlex using RealMasterMix (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and SYBR Green. Results were quantified using the Delta Delta C(T) method.43

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Excel 2004 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). The Student t test was used to calculate P values (2-tailed). P values of .05 or less are indicated in the figures by one asterisk; P values of .01 or less are indicated in the figures by 2 asterisks. Data are presented as mean values plus or minus standard deviation (SD).

Results

Stat5−/− embryos are severely anemic

Embryos lacking the entire Stat5 locus (ie, Stat5a/b) die during gestation or at latest perinatally (approximately 99%) with severe defects in diverse hematopoietic lineages.23,24 The previously demonstrated pivotal role of Stat5 in Epo signaling19–22 prompted us to analyze the function of Stat5 in erythropoiesis in detail. E13.5 Stat5−/− embryos and newborn Stat5−/− animals appeared paler than their wt littermates, particularly in the fetal liver region (Figure 1A). The relative abundance of erythroid cells in Stat5−/− fetal livers (approximately 80% of all cells) remained unchanged, as determined by staining for the panerythroid marker Ter-119, followed by flow cytometry (Figure 1B left). However, the size of Stat5−/− fetal livers in E13.5 embryos was visibly reduced and total fetal liver cellularity was decreased by 50% (n = 6), corresponding to a similar reduction in the total number of erythroid cells (Figure 1B right). Since anemia causes elevation of Epo levels44 to counteract hypoxia, sera from E16.5 or newborn wt and Stat5−/− animals were analyzed for Epo levels. These were highly elevated in Stat5−/− versus wt embryos (3.8 ± 0.6-fold; n = 5); newborn animals showed an even higher elevation (35.2 ± 5.1-fold; n = 5; Figure 1C). This strongly suggested that Stat5-deficient animals suffer from severe anemia. To determine the specific type of anemia, blood from E16.5 wt and Stat5−/− animals was analyzed (Table 1). Red blood cell counts of E16.5 Stat5−/− embryos were lowered to 1.0 plus or minus 0.3 × 106/mm3, in contrast to 2.4 plus or minus 0.4 × 106/mm3 in wt embryos. In line with this, hematocrit (Hct) of E16.5 Stat5−/− embryos was reduced to 9.8% plus or minus 0.7% compared with 31.4% plus or minus 1.8% in wt embryos. Likewise, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), hemoglobin content (Hgb), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) of E16.5 Stat5−/− blood was strongly reduced. These effects also were clearly visible in blood smears, showing hypochromic microcytic erythrocytes (Figure S1A,B, available on the Blood website; see the Supporting Materials link at the top of the online article).

Stat5−/− embryos are severely anemic. (A) wt and Stat5−/− E13.5 embryos (left) and newborn animals (right). (B) Ter-119+ erythroid cells (left) and fetal liver cellularity (right; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 6) of wt versus Stat5−/− fetal livers. (C) ELISA for Epo from serum of wt and knockout E16.5 embryos and newborns. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 5. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Stat5−/− embryos are severely anemic. (A) wt and Stat5−/− E13.5 embryos (left) and newborn animals (right). (B) Ter-119+ erythroid cells (left) and fetal liver cellularity (right; data are presented as mean ± SD; n = 6) of wt versus Stat5−/− fetal livers. (C) ELISA for Epo from serum of wt and knockout E16.5 embryos and newborns. Data are presented as means ± SD; n = 5. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Stat5−/− embryos mice display severe microcytosis

| E16.5 embryos . | Wild-type . | Stat5−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| RBC, 106/mm3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3** |

| Hct, % | 31.4 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 0.7** |

| Hgb, g/L | 91 ± 12 | 23 ± 7** |

| MCV, μm3 | 128.2 ± 3.7 | 95.9 ± 5.2** |

| MCH, pg | 37.5 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 0.7** |

| E16.5 embryos . | Wild-type . | Stat5−/− . |

|---|---|---|

| RBC, 106/mm3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.3** |

| Hct, % | 31.4 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 0.7** |

| Hgb, g/L | 91 ± 12 | 23 ± 7** |

| MCV, μm3 | 128.2 ± 3.7 | 95.9 ± 5.2** |

| MCH, pg | 37.5 ± 0.3 | 23.1 ± 0.7** |

Blood indices of E16.5 Stat5−/− embryos. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 15 each genotype.

RBC indicates red blood cell count; Hct, hematocrit; Hgb, hemoglobin content; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin.

*P < .05; **P < .01.

An additional cause for early lethality and high serum Epo levels could have been a lung defect leading to reduction in red cell oxygenation. Analysis of tissue sections from wt and Stat5−/− newborn animals, however, did not reveal any histologic differences (data not shown). Taken together, Stat5−/− mice suffer from microcytic anemia.

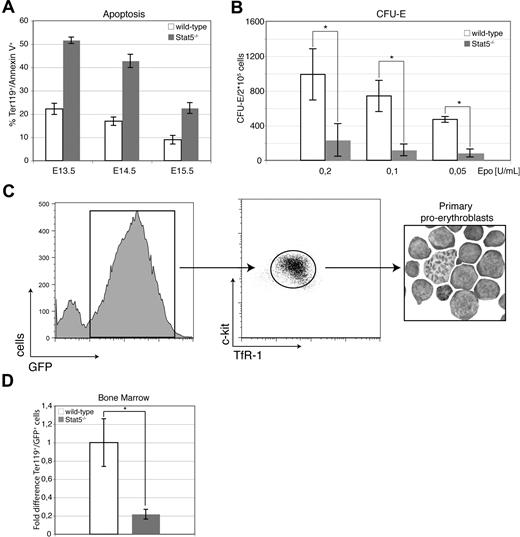

Loss of Stat5 causes enhanced apoptosis in the fetal liver

Hypomorphic Stat5ΔN/ΔN mice displayed enhanced erythroid cell death, which was attributed to reduced expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL.20,21 To determine apoptosis in Stat5−/− mice, freshly isolated fetal liver cells were stained for Ter-119 and apoptosis assessed by annexin V staining. In Stat5−/− embryos, the frequency of annexin V+ cells was enhanced more than 2-fold, regardless of developmental stage (Figure 2A). In line with this, Stat5−/− fetal liver cells showed a greater than 6-fold reduction of erythroid colony numbers in CFU-E assays regardless of Epo concentrations, supporting the notion that lack of functional Stat5 reduces cell survival (Figure 2B). In contrast, no significant alterations were observed in BFU-E assays (Figure S1C).

Loss of Stat5 results in increased levels of apoptosis in fetal liver cells. (A) Freshly isolated fetal livers from E13.5 to E15.5 were stained for Ter-119 and annexin V to determine rates of apoptosis (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3) for each genotype and time point. (B) CFU-E colonies derived from wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells using the indicated Epo concentrations (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (C) E13.5 fetal liver cells of wt and Stat5−/− embryos were infected with a retrovirus encoding GFP. TfR-1high/c-Kit+/GFP+ cells were isolated by FACS after 7 days under self-renewal conditions (cytospin; right panel). (D) A total of 1.5 × 107 TfR-1high/c-Kit+/GFP+ cells were injected into the tail vein of lethally irradiated mice (950 rad) and Ter-119+/GFP+ bone marrow cells were scored 3 days later (mean ± SD; n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Loss of Stat5 results in increased levels of apoptosis in fetal liver cells. (A) Freshly isolated fetal livers from E13.5 to E15.5 were stained for Ter-119 and annexin V to determine rates of apoptosis (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3) for each genotype and time point. (B) CFU-E colonies derived from wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells using the indicated Epo concentrations (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (C) E13.5 fetal liver cells of wt and Stat5−/− embryos were infected with a retrovirus encoding GFP. TfR-1high/c-Kit+/GFP+ cells were isolated by FACS after 7 days under self-renewal conditions (cytospin; right panel). (D) A total of 1.5 × 107 TfR-1high/c-Kit+/GFP+ cells were injected into the tail vein of lethally irradiated mice (950 rad) and Ter-119+/GFP+ bone marrow cells were scored 3 days later (mean ± SD; n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

To assess potential differences in viability of Stat5-deficient erythroid cells in an adult (bone marrow) versus an embryonic (fetal liver) microenvironment, short-term transplantation experiments were performed. Equal amounts of sorted GFP-expressing wt- or Stat5−/− proerythroblasts cultured from fetal livers (c-Kit+/TfR-1high/Ter-119− cells15 ) were injected into lethally irradiated wt recipients (Figure 2C). This setup was chosen to circumvent any influence of the well-known repopulation defect of Stat5-deficient hematopoietic stem cells.45–47 At 3 days after transplantation, bone marrow cells were harvested and scored for GFP+ mature Ter-119+ erythroid cells, as previously reported.48 In line with the preceding experiments, a 5-fold reduction in abundance of transplanted mature Stat5−/− versus wt cells was determined in the adult microenvironment (bone marrow; Figure 2D). Moreover, these data indicated a cell-autonomous survival defect of Stat5−/− erythroid cells.

Stat5 deficiency leads to reduced expression of antiapoptotic proteins

Consistent with the apoptotic phenotype described, Ter-119+ cells from Stat5−/− fetal livers showed decreased levels of Bcl-xL as compared with wt cells (Figure 3A left). Nevertheless, Bcl-xL protein levels in Stat5−/− cells were still approximately 50% of that of wt. This prompted us to analyze the expression of other antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. We focused on Mcl-1 for 3 reasons: (1) Mcl-1 is up-regulated during early erythroid commitment in human cells49 ; (2) its bone marrow–specific ablation reduces blood formation50 ; and (3) it appears to be regulated by Stat5.51–53 Indeed, Mcl-1 protein and mRNA expression were drastically reduced in Stat5-deficient cells (Figure 3A right; Figure 3B). To assess whether Mcl-1 is an Epo-inducible Stat5-regulated gene, primary wt and Stat5−/− erythroblasts were factor-deprived for 2 hours and subsequently restimulated with Epo for 30 minutes. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) revealed a 3.5-fold increase in Mcl-1 mRNA in Epo-stimulated cells, which was abrogated in Stat5-deficient cells (Figure 3C).

Loss of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 in Stat5−/− fetal liver. (A) Western blot of lysates from freshly isolated fetal livers or Ter-119+ and Ter-119− subfractions (separated using magnetic beads; “Methods”) for Bcl-xL (left; ERK, loading control). Western blot for Mcl-1 of 2 individual freshly isolated fetal livers of each genotype (right; eIF4E, loading control). (B) Quantitative PCR analysis for Mcl-1 mRNA isolated from the Ter-119+ subfraction of freshly isolated fetal liver cells (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3). (C) wt and Stat5−/− primary erythroblasts expanded for 5 days under self renewal conditions (“Methods”) were deprived of factors for 3 hours, followed by a 30-minute restimulation with 10 U/mL Epo. qPCR analysis for Mcl-1 (representative experiment; error bars are SD of experimental triplicates). (D) wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells were infected with retroviruses encoding GFP alone (murine stem cell virus [MSCV]), or Bcl-xL plus GFP, or Mcl-1 plus GFP from bicistronic constructs. After retroviral infection (72 hours), primary erythroblasts were cultivated for another 48 hours under self-renewal conditions (“Methods”) in the presence or absence of Epo. Rates of apoptosis were determined by flow cytometry for annexin V. One representative set of histograms from 3 independently performed experiments of GFP-gated annexin V+ cells at 48 hours of treatment is depicted. Arrowheads indicate increased levels of apoptosis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Loss of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 in Stat5−/− fetal liver. (A) Western blot of lysates from freshly isolated fetal livers or Ter-119+ and Ter-119− subfractions (separated using magnetic beads; “Methods”) for Bcl-xL (left; ERK, loading control). Western blot for Mcl-1 of 2 individual freshly isolated fetal livers of each genotype (right; eIF4E, loading control). (B) Quantitative PCR analysis for Mcl-1 mRNA isolated from the Ter-119+ subfraction of freshly isolated fetal liver cells (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3). (C) wt and Stat5−/− primary erythroblasts expanded for 5 days under self renewal conditions (“Methods”) were deprived of factors for 3 hours, followed by a 30-minute restimulation with 10 U/mL Epo. qPCR analysis for Mcl-1 (representative experiment; error bars are SD of experimental triplicates). (D) wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells were infected with retroviruses encoding GFP alone (murine stem cell virus [MSCV]), or Bcl-xL plus GFP, or Mcl-1 plus GFP from bicistronic constructs. After retroviral infection (72 hours), primary erythroblasts were cultivated for another 48 hours under self-renewal conditions (“Methods”) in the presence or absence of Epo. Rates of apoptosis were determined by flow cytometry for annexin V. One representative set of histograms from 3 independently performed experiments of GFP-gated annexin V+ cells at 48 hours of treatment is depicted. Arrowheads indicate increased levels of apoptosis. *P < .05; **P < .01.

To test whether exogenous Mcl-1 provides protection against apoptosis to erythroid cells, primary wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells were transduced with retroviral constructs encoding GFP, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1. Erythroblasts were cultivated for 48 hours in the presence or absence of Epo, and apoptosis was determined by flow cytometry. Ectopic expression of either Mcl-1 or Bcl-xL completely prevented apoptosis of wt as well as Stat5 knockout erythroblasts upon Epo withdrawal (Figure 3D).

The decrease of fetal liver size and cellularity in Stat5−/− embryos could also have been due to reduced proliferation of erythroid cells, as suggested by the known ability of Stat5 to enhance expression of proliferation-promoting genes such as c-Myc, Cyclin D2 and D3, or oncostatin M.14,23,54,55 Cell division kinetics of erythroid cells in vivo and in vitro, however, were similar in Stat5−/− and wt cells (Figure S2; Document S1).

Taken together, Stat5-deficient fetal liver erythroid cells were massively apoptotic. This effect could be attributed to reduction of Bcl-xL levels together with complete loss of Mcl-1, translating into massive decrease of fetal liver cellularity.

TfR-1 expression is strongly reduced in Stat5−/− erythroid cells

To analyze whether Stat5-deficient mice had a defect in erythroid lineage commitment, wt and Stat5−/− fetal livers were analyzed for the presence of megakaryocytic-erythroid progenitors56,57 (MEPs), the first erythroid-committed progenitor detectable by flow cytometry. Interestingly, we observed a 2-fold increase of the MEP compartment in Stat5-deficient fetal livers (Figure S3), suggesting a compensatory attempt to counteract the increased erythroid cell death during definitive erythropoiesis.

To determine whether the anemia in Stat5−/− embryos was due to a defect in erythroid differentiation, fetal liver cells were analyzed for erythroid markers Ter-119 and TfR-1. This combination allows staging of maturing erythroid cells from immature progenitors (TfR-1low Ter-119low) over an intermediate stage (TfR-1high Ter-119high) to late orthochromatophilic erythroblasts (TfR-1neg Ter-119high; Figure 4A left; gates R1 to R5, increasing maturity58 ). Stat5-deficient and wt fetal livers contained cells of all differentiation stages at indistinguishable frequencies (Figure 4A). For detailed morphologic analysis, wt and Stat5−/− fetal liver cells were sorted according to their cell-surface marker phenotype (R2-R5), spun onto glass slides, and subsequently stained with either May-Grunwald Giemsa or Benzidine-Wright Giemsa (Figure S4). No apparent morphologic differences in maturity between wt and Stat5−/− cells were observed. Thus, the reduction in fetal liver cellularity (Figure 1B) was probably not due to differentiation arrest at a distinct step of maturation. We did, however, observe a reproducible decrease in TfR-1 cell-surface expression, which prompted us to align the gating strategy accordingly.

Cell-surface expression of TfR-1 is strongly reduced in Stat5−/− erythroid progenitors. (A) Representative flow cytometry histograms of E13.5 wt and Stat5−/− fetal liver cells stained for the erythroid markers TfR-1 and Ter-119 (left). The sequence from gate R1 (TfR-1low Ter-119low) to gate R5 (TfR-1− Ter-119high) represents development from the most immature erythroid progenitors (late BFU-E; CFU-E) to mature erythroid cells (orthochromatic erythroblasts; reticulocytes).58 Quantification of gates R1 to R5 (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4) (right). (B) Cell-surface expression of TfR-1 of Ter-119high gated wt (dark gray line) or Stat5−/− (light gray line) fetal liver cells (left). Quantification of TfR-1 cell-surface expression of wt and Stat5−/− fetal livers (right; data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (C) Expression of TfR-1 mRNA from lysates of freshly isolated wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3). Expression was normalized on hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) levels. (D) Western blot analysis of freshly isolated wt and Stat5−/− fetal liver cell lysates for TfR-1. ERK was used as loading control. (E) Densitometric quantification of TfR-1 Western blot in 3D (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (F) Primary wt fetal liver erythroblasts were stimulated with Epo for 30 minutes and ChIP for Stat5 was performed. DNA from Epo-stimulated primary wt erythroblasts was recovered using 2 different antisera directed against N- or C-terminal epitopes (αS5 C, αS5 N). Specific PCR products from Stat5-binding sites GAS 1, GAS 2, and GAS 3 in TfR-1 intron 159 were only obtained with Stat5-specific antibodies but not with control IgGs. PCR for the genuine Stat5 site in the CIS promoter was used as positive control. (G) Primary wt fetal liver–derived erythroblasts were factor depleted for 2.5 hours, followed by 1.5 hours of Epo stimulation (10 U/mL). TfR-1 mRNA expression was scored by qPCR normalized on HPRT (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (H) Iron concentration in freshly isolated fetal liver lysates determined via atomic absorption spectrometry (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4; for experimental details, see Document S1). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Cell-surface expression of TfR-1 is strongly reduced in Stat5−/− erythroid progenitors. (A) Representative flow cytometry histograms of E13.5 wt and Stat5−/− fetal liver cells stained for the erythroid markers TfR-1 and Ter-119 (left). The sequence from gate R1 (TfR-1low Ter-119low) to gate R5 (TfR-1− Ter-119high) represents development from the most immature erythroid progenitors (late BFU-E; CFU-E) to mature erythroid cells (orthochromatic erythroblasts; reticulocytes).58 Quantification of gates R1 to R5 (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4) (right). (B) Cell-surface expression of TfR-1 of Ter-119high gated wt (dark gray line) or Stat5−/− (light gray line) fetal liver cells (left). Quantification of TfR-1 cell-surface expression of wt and Stat5−/− fetal livers (right; data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (C) Expression of TfR-1 mRNA from lysates of freshly isolated wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3). Expression was normalized on hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT) levels. (D) Western blot analysis of freshly isolated wt and Stat5−/− fetal liver cell lysates for TfR-1. ERK was used as loading control. (E) Densitometric quantification of TfR-1 Western blot in 3D (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (F) Primary wt fetal liver erythroblasts were stimulated with Epo for 30 minutes and ChIP for Stat5 was performed. DNA from Epo-stimulated primary wt erythroblasts was recovered using 2 different antisera directed against N- or C-terminal epitopes (αS5 C, αS5 N). Specific PCR products from Stat5-binding sites GAS 1, GAS 2, and GAS 3 in TfR-1 intron 159 were only obtained with Stat5-specific antibodies but not with control IgGs. PCR for the genuine Stat5 site in the CIS promoter was used as positive control. (G) Primary wt fetal liver–derived erythroblasts were factor depleted for 2.5 hours, followed by 1.5 hours of Epo stimulation (10 U/mL). TfR-1 mRNA expression was scored by qPCR normalized on HPRT (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (H) Iron concentration in freshly isolated fetal liver lysates determined via atomic absorption spectrometry (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4; for experimental details, see Document S1). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Accumulation of hemoglobin is the hallmark of terminal erythropoiesis, requiring an enormous up-regulation of iron intake via increased expression of TfR-1. Quantification of TfR-1 levels in Stat5-deficicient versus wt cells by flow cytometry revealed a greater than 2-fold reduction in knockout cells (Figure 4B). This was confirmed at the mRNA level (Figure 4C) and further corroborated by Western blot analysis of wt, Stat5+/−, and Stat5−/− fetal liver cell lysates (Figure 4D,E). A recent report described functional Stat5-binding sites (interferon-gamma–activated sequence [GAS] elements) in the first intron of the TfR-1 gene, using an erythroleukemic cell line expressing a constitutively active Stat5 variant.59 To corroborate these data, we decided to analyze DNA binding of endogenous Stat5 to these elements in primary fetal liver erythroblasts after Epo stimulation by chromatin immunoprecipitation (Figure 4F). Indeed, DNA binding of Stat5 to all 3 sites analyzed was confirmed and apparently resulted in an Epo-induced increase of TfR-1 mRNA as quantified by qPCR (Figure 4G). As expected from the well-known inverse relation in expression of TfR-1 to the iron-storage protein ferritin,30 Stat5−/− cells showed elevated levels of ferritin protein (Figure S5).

As a direct consequence of reduced TfR-1 cell-surface expression, we observed a significant reduction of intracellular iron (approximately 40%) in freshly isolated Stat5−/− fetal livers as measured by atomic absorption spectrometry (Figure 4H), further supporting the idea of altered iron metabolism in Stat5−/− cells. Reduced iron availability leads to a drop in heme synthesis,60 known to result in activation of heme-regulated inhibitor (HRI).61 This kinase, via inactivation of translation initiation factor eIF2-alpha, throttles expression of globins to ensure that heme, alpha-globin, and beta-globin are always synthesized at the appropriate ratio of 4:2:2.61 To test whether this regulatory circuit was disturbed in Stat5−/− erythroid cells, an abundance of globin mRNAs in lysates from erythroid cells sorted out of wt or Stat5−/− fetal livers were analyzed by qPCR. Indeed, relative levels of both globin mRNAs were significantly reduced in Stat5−/− cells; moreover, eIF2-alpha showed the expected increase in phosphorylation (Figure S6). In summary, these data demonstrated that Stat5−/− erythroid cells were severely iron-deficient.

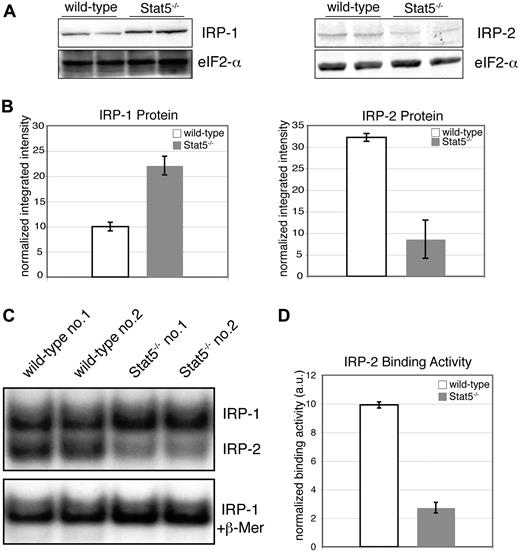

IRP-2 expression and mRNA-binding activity is reduced in Stat5-deficient cells

Stabilization of TfR-1 mRNA by binding of IRP-1 and IRP-2 is considered the predominant mechanism to satisfy the iron demand of proliferating cells.30,31 A possible activation of IRPs by Epo has been discussed.62,63 Accordingly, Western blot analyses for IRP-1 and IRP-2 from lysates of wt and Stat5−/− primary erythroblasts revealed a striking, 5-fold down-regulation of IRP-2 in Stat5 knockout cells (Figure 5A,B right), accompanied by a 2-fold up-regulation in IRP-1 expression. IRP-1 and IRP-2 mRNA levels were similarly changed in Stat5-deficent cells (data not shown). Determination of IRP-2 RNA binding in Stat5−/− cells using in vitro–transcribed, radioactively labeled IRE probes in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs; Figure 5C) showed a similar decrease of IRP-2 activity (Figure 5D). Given the important role of IRP-2 in TfR-1 expression in erythroid cells,38,39 these data strongly suggested that the decrease of IRP-2 was an additional cause for reduction of TfR-1 cell-surface expression.

Stat5-deficient erythroid cells display reduced IRP-2 expression and mRNA-binding activity. (A) Western blot analysis of primary wt and Stat5−/− erythroblast lysates for IRP-1 (left panel) and IRP-2 (right panel). (B) Quantification of Western blot analysis from panel A (data are presented as means ± SD). Samples were normalized on eIF4E as levels and quantified using the Odyssey infrared imaging system. (C) Two representative lysates each of wt and Stat5−/− erythroblasts were subjected to RNA-EMSAs for IRP-1 and IRP-2 using an IRE-RNA probe corresponding to the IRE of mouse ferritin heavy chain64 (for experimental details, see Document S1). (D) Quantification of IRP-2–binding activity (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

Stat5-deficient erythroid cells display reduced IRP-2 expression and mRNA-binding activity. (A) Western blot analysis of primary wt and Stat5−/− erythroblast lysates for IRP-1 (left panel) and IRP-2 (right panel). (B) Quantification of Western blot analysis from panel A (data are presented as means ± SD). Samples were normalized on eIF4E as levels and quantified using the Odyssey infrared imaging system. (C) Two representative lysates each of wt and Stat5−/− erythroblasts were subjected to RNA-EMSAs for IRP-1 and IRP-2 using an IRE-RNA probe corresponding to the IRE of mouse ferritin heavy chain64 (for experimental details, see Document S1). (D) Quantification of IRP-2–binding activity (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). *P < .05; **P < .01.

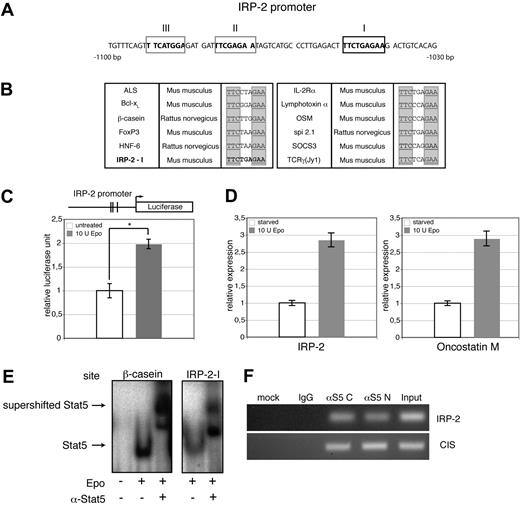

IRP-2 is a direct transcriptional target of Stat5

To test a possible direct role of Stat5 in regulating IRP-2 expression, we analyzed the IRP-2 promoter in detail. A region 1030 to 1100 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site contained one perfect Stat5 DNA-binding site (TTCN3GAA)65 plus 2 adjacent low-affinity Stat5 response elements with a mismatch in one half-site of the inverted repeat (Figure 6A). Annotated Stat5 sites24,65 together with the IRP-2 sequence I suggested that the latter fulfilled bioinformatic criteria for perfect Stat5 binding (Figure 6B).

Loss of Stat5 directly decreases IRP-2 gene expression. (A) Sequence of the IRP-2 promoter −1030 bp to −1100 bp upstream of the transcription start, showing one perfect GAS site (boxed in black) and 2 GAS sites with one mismatch (boxed in gray). (B) Multiple perfect Stat5 sites taken from Yao et al26 and Ehret et al65 together with the IRP-2-I. (C) Luciferase reporter assay using a DNA fragment ranging from 2 kb immediately upstream of the predicted IRP-2 transcription start site. Vertical lines indicate the approximate positions of the putative Stat5 response elements. 293T cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding IRP-2-firefly-luciferase, renilla-luciferase, Stat5a, and EpoR. Cells were treated with 10 U/mL Epo or left untreated, and luminescence was scored 3 hours later. Transfection efficiencies were normalized to renilla-luciferase activity (representative experiment; error bars are SD of experimental triplicates). (D) Epo-dependent induction of endogenous IRP-2 and oncostatin M analyzed via quantitative PCR in murine erythroid leukemia cells serum deprived for 3 hours, followed by stimulation with 10 U/mL Epo (1 hour). Quantitative PCR was normalized on HPRT (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (E) 293T cells were cotransfected with constructs for EpoR and wt Stat5a, followed by 30 minutes of stimulation with 10 U Epo/mL. Whole-cell extracts of these cells were subjected to EMSAs using either the IRP-2-I oligonucleotide (left) or β-casein oligonucleotide as positive control (right). Respective arrows indicate Stat5 DNA complexes and Stat5 DNA complex supershifts. (F) Primary wt fetal liver erythroblasts were stimulated with Epo for 30 minutes, and ChIP for Stat5 was performed. Recovered DNA was analyzed for the presence of promoters of IRP-2 and CIS (positive control) by PCR. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Loss of Stat5 directly decreases IRP-2 gene expression. (A) Sequence of the IRP-2 promoter −1030 bp to −1100 bp upstream of the transcription start, showing one perfect GAS site (boxed in black) and 2 GAS sites with one mismatch (boxed in gray). (B) Multiple perfect Stat5 sites taken from Yao et al26 and Ehret et al65 together with the IRP-2-I. (C) Luciferase reporter assay using a DNA fragment ranging from 2 kb immediately upstream of the predicted IRP-2 transcription start site. Vertical lines indicate the approximate positions of the putative Stat5 response elements. 293T cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding IRP-2-firefly-luciferase, renilla-luciferase, Stat5a, and EpoR. Cells were treated with 10 U/mL Epo or left untreated, and luminescence was scored 3 hours later. Transfection efficiencies were normalized to renilla-luciferase activity (representative experiment; error bars are SD of experimental triplicates). (D) Epo-dependent induction of endogenous IRP-2 and oncostatin M analyzed via quantitative PCR in murine erythroid leukemia cells serum deprived for 3 hours, followed by stimulation with 10 U/mL Epo (1 hour). Quantitative PCR was normalized on HPRT (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 4). (E) 293T cells were cotransfected with constructs for EpoR and wt Stat5a, followed by 30 minutes of stimulation with 10 U Epo/mL. Whole-cell extracts of these cells were subjected to EMSAs using either the IRP-2-I oligonucleotide (left) or β-casein oligonucleotide as positive control (right). Respective arrows indicate Stat5 DNA complexes and Stat5 DNA complex supershifts. (F) Primary wt fetal liver erythroblasts were stimulated with Epo for 30 minutes, and ChIP for Stat5 was performed. Recovered DNA was analyzed for the presence of promoters of IRP-2 and CIS (positive control) by PCR. *P < .05; **P < .01.

To test whether there was a direct transcriptional induction of IRP-2 by Stat5, the 2 kb fragment of the IRP-2 promoter upstream of the predicted transcription start site, comprising all 3 putative Stat5 response elements (REs), was inserted into a firefly-luciferase reporter gene construct. 293T cells were cotransfected with Stat5a and EpoR cDNAs together with the respective reporter construct. Transfected cells were stimulated with Epo or left untreated. Epo-treated cells displayed a significant increase of luminescence over untreated controls (Figure 6C). Direct Epo-induced expression of endogenous IRP-2 and oncostatin M (a bona fide Stat5 target gene) was demonstrated in murine erythroid leukemia cells: following 3 hours of factor deprivation, cells were restimulated for 1 hour with Epo and mRNA expression levels determined by qPCR. Epo stimulation induced expression of IRP-2 as well as oncostatin M about 3-fold (Figure 6D).

To further substantiate that IRP-2 is a direct target of Stat5, EMSAs were performed. 293T cells were cotransfected with constructs encoding EpoR and murine Stat5a. Transfected cells were Epo-stimulated or left untreated. Extracts were subsequently subjected to EMSAs using radiolabeled oligonucleotides encompassing either the newly identified Stat5-RE I of the IRP-2 promoter or a well-described Stat5-RE probe from the bovine β-casein promoter as positive control. For supershifts, a serum directed against the C-terminus of Stat5 was added to the oligonucleotide/lysate mixture. Stat5-DNA complexes were clearly evident in Epo-stimulated extracts, using both the IRP-2-I or the β-casein probe, as these complexes were readily super-shifted upon addition of anti-Stat5 serum (Figure 6E). Similar results were obtained using Epo-stimulated cells transfected with murine Stat5b (data not shown).

To test whether Stat5 recognizes one of these putative DNA-binding sites in vivo, we finally performed chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments using 2 different antisera directed against N- or C-terminal epitopes in Stat5. PCR analysis of immunoprecipitated Stat5-DNA complexes from Epo-stimulated primary wt erythroblasts yielded a PCR product representing Stat5-binding sites in the IRP-2 promoter in both specific Stat5 ChIPs, but not in control IgG ChIP experiments (Figure 6F).

Together, these results indicated that Stat5 is directly involved in the control of TfR-1 transcription as well as in the modulation of its mRNA stability by regulating expression of IRP-2.

Discussion

In this paper cooperating mechanisms underlying the erythroid defect leading to microcytic anemia in Stat5−/− mice were uncovered, demonstrating a novel direct link between the EpoR-Stat5 axis and regulation of iron metabolism in vivo. First, Stat5−/− fetal livers showed reduced cellularity due to massively enhanced apoptosis of maturing erythroid cells, apparently caused by defective expression of the antiapoptotic genes Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL. Second, Stat5−/− erythroid cells exhibited reduced expression of IRP-2 and TfR-1, resulting in a large decrease of TfR-1 cell surface expression, iron uptake, and globin synthesis. Together, these mechanisms appear to be sufficient to explain the severe anemia of Stat5−/− animals.

Complete ablation of Stat5 leads to early lethality

None of the conditional Stat5 knockout models created so far in multiple cell types such as hemangioblasts (Stat5fl/fl Tie2-Cre),59 B cells (CD19-Cre),66 T cells (CD4-Cre, Lck-Cre),23,24 hepatocytes (albumin-Cre, albumin-alpha-fetoprotein-Cre),25,67 pancreatic β cells/hypothalamus (Rip-Cre),68 endocrine/exocrine pancreas progenitors (Pdx1-Cre),68 or skeletal muscle (Myf5-Cre)69 die during fetal development. In contrast, ablation of Stat5 in the entire organism resulted in mortality8 during gestation or at latest shortly after birth. Since Epo−/−, EpoR−/−, and Jak2−/− mice all die in utero at E13.5 due to defects in definitive erythropoiesis and given the prominent role of Stat5 in EpoR signaling, it was unexpected that a few Stat5−/− embryos developed to term.

There are several possible explanations for the discrepancy in phenotypes. First, we detected high levels of pY-Stat1 and pY-Stat3 in Stat5-deficient cultivated primary erythroblasts as well as in lysates from freshly isolated fetal livers but not in wt counterparts (M.A.K., F.G., unpublished data). This is in line with increased pY-Stat1 and pY-Stat3 levels found upon liver-specific Stat5 deletion.67,70,71 Since Stat3 and Stat5 response elements are similar,65 increased activation of Stat3 might partially compensate for loss of Stat5. Second, the anemia of Stat5−/− embryos led to a compensatory elevation of Epo levels in the serum, which was most pronounced in the few newborn animals. This might contribute to prolonged survival mediated by hyperactivation of Stat5-independent EpoR signaling. Third, Stat5-deficient erythroid cells exhibited elevated levels of phosphorylated eIF2-alpha, indicative for an active “integrated stress response” (ISR), presumably via the kinase HRI.72 In mouse models for the red blood cell disorders erythropoietic protoporphyria and β-thalassemia, ablation of HRI exacerbated the phenotype of these diseases.72 Thus, the modulation of translational efficiency to balance heme and globin production could represent another protective mechanism accounting for the “mild” erythroid phenotype of Stat5−/− animals. Nevertheless, the ultimate reason for the early death of the animals remains to be determined.

Stat5 is not essential for erythroid differentiation

Earlier studies addressing the role of Stat5 (ie, Stat5a and Statb) in erythropoiesis were performed with Stat5ΔN/ΔN animals. These mice are born, viable, and show only a mild erythroid phenotype.20,21 Stat5ΔN/ΔN animals express a N-terminally truncated Stat5, which still activates target genes.22 Here, we used Stat5−/− mice lacking the entire Stat5a/b locus.8 Animals lacking other components of Epo signaling upstream of Stat5 (Epo, EpoR, or Jak2),2 all die in utero around E13.5 due to a block in definitive erythropoiesis. If Stat5 was the only crucial target of this pathway, full Stat5 knockout animals should show a similarly severe phenotype. Indeed, Stat5-deficient animals display erythroid defects and die at latest after birth. Although Stat5 is essential for differentiation of other hematopoietic lineages like maturation of pre-pro– to pro-B cells,23,24 or in formation of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells,26 the observed block in erythroid maturation in vivo was not complete. The presence of erythroid cells at all developmental stages in Stat5−/− embryos strongly argued against an absolutely essential function of Stat5 in erythroid development. Nevertheless, there were defects in hemoglobinization of Stat5−/− erythroid cells, which may have several causes. For instance, it could decrease through direct defects in the erythroid differentiation program and/or through a secondary response to iron deficiency.

Involvement of Stat5 in iron metabolism

The most striking observation in the peripheral blood morphology of Stat5−/− animals was an apparent microcytic hypochromic anemia. This type of anemia, characterized by decreased mean corpuscular volume and reduced mean cell hemoglobin, is frequently associated with iron deficiency. Thus, it was tempting to investigate the molecular players involved.

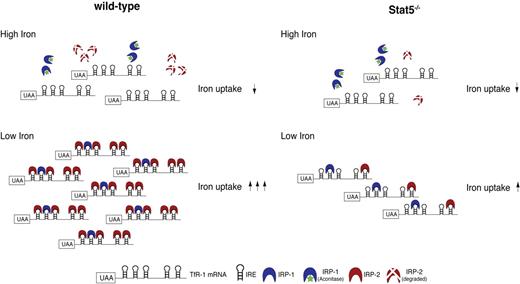

The normal adaptive response to low iron is the well-characterized feedback regulation that increases TfR-1 mRNA stability upon binding of IRPs to its 3′-UTR (Figure 7). In Stat5−/− cells, this response apparently was impeded as delineated from the reduced expression of TfR-1, which in turn was the direct result of decreased IRP-2 protein levels. This mechanistic link was further substantiated by the measured reduction in total intracellular iron in Stat5−/− fetal livers, finally resulting in decreased globin mRNA expression. It remained unclear, however, whether a connection between Stat5 and IRP-2 expression existed. The promoter region of the IRP-2 gene contains 3 adjacent potential binding sites for Stat5, which indeed turned out to be functional. Moreover, qPCR showed reduced IRP-2 mRNA abundance in the absence of Stat5. Thus, one could envision a chain of events in Stat5-deficient erythroid cells, starting with decreased IRP-2 and TfR-1 expression, resulting in a net decrease of TfR-1 mRNA stability and abundance, followed by diminished TfR-1 surface expression. The consequence would be insufficient iron uptake (even in iron-depleted cells), ultimately leading to decreased heme synthesis, activation of the integrated stress response pathway and reduced globin mRNA translation. Interestingly, no functional compensation for low IRP-2 levels by the highly homologous IRP-1 protein was observed. This is in line with in vivo data from corresponding IRP-1 or IRP-2 knockout animals,38,39 which indicated that IRP-2 is the predominant regulatory factor modulating TfR-1 mRNA stability. While ablation of IRP-1 produced no overt phenotype, loss of IRP-2 resulted in hypochromic microcytic anemia due to reduced TfR-1 expression, a phenotype reminiscent to the one of Stat5 knockout animals described here. Accordingly, lowering the expression of TfR-1 by 50% led to a similar phenotype, as TfR-1+/− mice also displayed the same type of anemia.73 It should be mentioned, however, also other conditions are known to result in microcytosis, including ablation of the genuine Stat5 target Pim-1.9

Model for involvement of Stat5 in iron uptake. Left side shows that in iron-replete cells, IRP-1 is converted into cytosolic aconitase (catalyzes isomerization of citrate to isocitrate in the citric acid cycle and exhibits no mRNA-binding affinity; green asterisk) and IRP-2 is degraded. Therefore, both cannot bind to IREs in the 3′UTR of TfR-1 mRNA. Free unprotected IREs in turn enhance degradation rates of TfR-1 mRNA, resulting in reduced iron uptake. In iron-depleted cells, IRP-1 and IRP-2 bind to the respective IREs, thereby stabilizing TfR-1 mRNA, resulting in increased iron uptake. The right side shows Stat5−/−. Due to lack of Stat5, basal TfR-1 transcript abundance is reduced in comparison to wt cells. In addition, Stat5 deficiency further results in decreased levels of IRP-2 and, in consequence, a reduction of binding to IREs in the 3′UTR of TfR-1 mRNA and decreased transcript stabilization. Together, this constitutes a double-negative effect on erythroid iron uptake even in a situation of high iron demand, as in iron-deficiency anemia. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Model for involvement of Stat5 in iron uptake. Left side shows that in iron-replete cells, IRP-1 is converted into cytosolic aconitase (catalyzes isomerization of citrate to isocitrate in the citric acid cycle and exhibits no mRNA-binding affinity; green asterisk) and IRP-2 is degraded. Therefore, both cannot bind to IREs in the 3′UTR of TfR-1 mRNA. Free unprotected IREs in turn enhance degradation rates of TfR-1 mRNA, resulting in reduced iron uptake. In iron-depleted cells, IRP-1 and IRP-2 bind to the respective IREs, thereby stabilizing TfR-1 mRNA, resulting in increased iron uptake. The right side shows Stat5−/−. Due to lack of Stat5, basal TfR-1 transcript abundance is reduced in comparison to wt cells. In addition, Stat5 deficiency further results in decreased levels of IRP-2 and, in consequence, a reduction of binding to IREs in the 3′UTR of TfR-1 mRNA and decreased transcript stabilization. Together, this constitutes a double-negative effect on erythroid iron uptake even in a situation of high iron demand, as in iron-deficiency anemia. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Involvement of Stats in iron metabolism might even be a more general mechanism. Hepcidin,74,75 the dominant regulator of dietary iron absorption in enterocytes and iron release from macrophages, is a direct Stat3 target gene74,75 : upon infection, the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 promotes hepcidin expression via Stat3, trapping iron in macrophages, resulting in decreased plasma iron concentrations. Hepcidin expression is decreased by hypoxia and anemia, directly responding to increased Epo levels.74–76 Thus, its regulation in the anemia resulting from Stat5 deficiency may be of interest in future studies.

Stat5−/− fetal liver cells exhibit high levels of apoptosis

In erythropoiesis, up-regulation of Bcl-xL was found to be defective in Stat5ΔN/ΔN erythroid cells.20,21 Other studies, however, suggested that Bcl-xL prevents apoptosis only of late-stage erythroblasts,11,77 but not directly via EpoR.77 Upon readdressing this question in mice that are fully devoid of Stat5, we observed a reduction in Bcl-xL levels of about 50% in fetal liver erythroid cells. Furthermore, Mcl-1 expression in Stat5−/− erythroid cells was analyzed, based on the finding that this Bcl-2 gene family member could be a Stat5 target gene.52,53,78 Indeed, Mcl-1 was completely absent in Stat5−/− fetal liver cells, whereas Epo stimulation of wt primary erythroblasts led to a 3.5-fold increase of Mcl-1 mRNA. Furthermore, reintroduction of Mcl-1 or Bcl-xL completely prevented apoptosis of wt as well as Stat5 knockout erythroblasts upon Epo withdrawal.

Besides the finding that Mcl-1 is a Stat5-dependent Epo target gene, down-regulation of Mcl-1 in Stat5−/− erythroid cells could also occur through an additional mechanism, which is induced through iron deficiency in Stat5 knockout animals. Recently, it was suggested that Mcl-1 levels decrease after activation of the phospho-eIF2-alpha–mediated ISR pathway already mentioned.79–81 eIF2-alpha phosphorylation can be induced by different kinases in response to several stress stimuli,82 including HRI. Iron deficiency activates HRI, which in turn phosphorylates eIF2-alpha on its inhibitory Ser51, resulting in global reduction of mRNA translation,61 which immediately affects Mcl-1, as it is a highly unstable protein.83 The observed reduced iron levels, together with elevated eIF2-alpha phosphorylation in Stat5−/− primary erythroblasts, suggested an active ISR in Stat5−/− cells. Hence, loss of Stat5 could lead to a direct decrease of Mcl-1 mRNA, but alternatively also to a down-regulation of Mcl-1 protein due to iron deficiency–induced ISR. Taken together, the apoptosis in Stat5−/− fetal livers most probably reflects a composite effect of reduced levels of Bcl-xL and loss of Mcl-1.

This contribution should help to clarify the long-discussed role of Stat5 in erythropoiesis in vivo: We identify Stat5 as a key factor regulating erythroid iron metabolism in vivo and, additionally, link the antiapoptotic machinery of erythroid cells with their iron uptake system.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank L. 6ennighausen for providing Stat5−/− mice, G. Stengl for FACS sorting, G. Litos for technical assistance, and M. von Lindern for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to R. S. Eisenstein and T. Roault for antibodies against IRP-1 and IRP-2, respectively.

This work was supported by grants WK-001 (to F.G. and M.A.K.) and SFB F028 (to H.B., R.M., and E.W.M.) from the Austrian Research Foundation, Fonds zur Föderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung (FWF), and the Herzfelder Family Foundation (to E.W.M.).

Authorship

Contribution: M.A.K., F.G., H.G., M.S., M.A., and B.K. conducted experiments; M.A.K. and E.W.M. designed experiments and interpreted results; H.B. contributed essential reagents and worked on the draft of the manuscript; and M.A.K., R.M., and E.W.M. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ernst W. Müllner, Max F. Perutz Laboratories, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Medical University of Vienna, Dr. Bohr-Gasse 9, A-1030 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: ernst.muellner@meduniwien.ac.at.

References

Author notes

*M.A.K. and F.G. contributed equally to this article.

![Figure 3. Loss of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 in Stat5−/− fetal liver. (A) Western blot of lysates from freshly isolated fetal livers or Ter-119+ and Ter-119− subfractions (separated using magnetic beads; “Methods”) for Bcl-xL (left; ERK, loading control). Western blot for Mcl-1 of 2 individual freshly isolated fetal livers of each genotype (right; eIF4E, loading control). (B) Quantitative PCR analysis for Mcl-1 mRNA isolated from the Ter-119+ subfraction of freshly isolated fetal liver cells (data are presented as means ± SD; n = 3). (C) wt and Stat5−/− primary erythroblasts expanded for 5 days under self renewal conditions (“Methods”) were deprived of factors for 3 hours, followed by a 30-minute restimulation with 10 U/mL Epo. qPCR analysis for Mcl-1 (representative experiment; error bars are SD of experimental triplicates). (D) wt or Stat5−/− fetal liver cells were infected with retroviruses encoding GFP alone (murine stem cell virus [MSCV]), or Bcl-xL plus GFP, or Mcl-1 plus GFP from bicistronic constructs. After retroviral infection (72 hours), primary erythroblasts were cultivated for another 48 hours under self-renewal conditions (“Methods”) in the presence or absence of Epo. Rates of apoptosis were determined by flow cytometry for annexin V. One representative set of histograms from 3 independently performed experiments of GFP-gated annexin V+ cells at 48 hours of treatment is depicted. Arrowheads indicate increased levels of apoptosis. *P < .05; **P < .01.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/112/9/10.1182_blood-2008-02-138339/5/m_zh80200826060003.jpeg?Expires=1765928249&Signature=1NWB9J~qO89dBNQmwugiNls0LZWWLH6SgKx8-cFP~FEiVMdTRqyn5jXX4WZFIg93rZykcrahAIvVbBSgbPj9HeGxtSz3iU3frgjGOmQIkK8-1gBXBtBjQ~s~3C7PveR~HaueFA9lXjyb-99NJtK6WLneKeZmNXkk~IJ4HZ3cPEEmQmaLqaqWE~uARkpBAo-2B8oQFg1wgBPv~MY5yzkadsR~Y6pRSIb5iAvPGAAk~iXJZFHB41CyuGUoCVZCLvSFWFBnp-uBzxcpsP29oAmOxDCy1wiazz14qc4pgdkD-vf~T58BPAskZ-D033sLJanER043krbsSF8yY8ZAUPhYWg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal