In this issue of Blood, Kang and colleagues show that 4.1R localizes to the immunologic synapse to negatively regulate T-cell activation. These findings contrast with other FERM family members and show that FERM proteins affect T-cell function through multiple mechanisms.

T-cell activation requires the coordination of signaling events downstream of T-cell receptor (TCR) ligation with intracellular cytoskeletal reorganization, leading to T-cell effector function. Regulators of the actin cytoskeleton have been shown to be critical mediators of the formation of the immunologic synapse and productive T-cell activation.1 4.1 proteins belong to a larger FERM (FERM: F-4.1, E-ezrin, R-radixin, M-moesin) family of cytoskeletal regulators, which also include the ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin) proteins. In T cells, ERM proteins were initially identified as canonical markers of the pole opposite to the immunologic synapse (distal pole complex, DPC),2,3 and perturbing ERM function leads to defects in T-cell activation.4 4.1R is a key player in determining erythrocyte shape and function, but until now, its function in T cells has been unknown. This new study by Kang et al provides the first description of the role of 4.1R in T cells.5

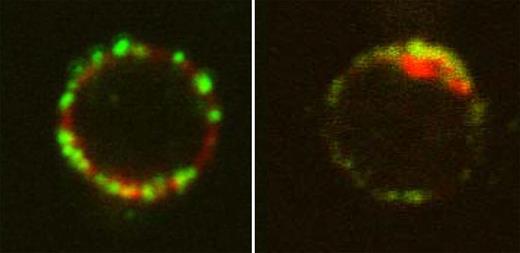

Localization of 4.1R in T cells. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 6128.

Localization of 4.1R in T cells. See the complete figure in the article beginning on page 6128.

Kang and colleagues find that, compared with wild-type T cells, 4.1R-deficient T cells are hyperproliferative. 4.1R deficiency also leads to increased cytokine production by T cells and hyperphosphorylation of 2 key signaling intermediates downstream of T-cell activation, LAT and ERK. 4.1R colocalizes with LAT at the site of TCR activation (see figure) and mediates its effects on T-cell activation through direct association with LAT. 4.1R binding to LAT inhibits LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70. These results show that 4.1R is a negative regulator of T-cell function through effects on LAT phosphorylation.

Interestingly, while 4.1R and ERM proteins share significant sequence homology, this report shows that 4.1R and ERM family members play fundamentally opposing roles in their regulation of T-cell activation. ERM proteins move negative regulators to the DPC to positively regulate T-cell activation, while 4.1R localizes to the immunologic synapse to negatively regulate T-cell signaling. 4.1R negatively regulates T-cell activation via binding to LAT to inhibit LAT phosphorylation. Like ERM proteins, 4.1R binds both the actin cytoskeleton and signaling molecules downstream of TCR ligation. However, unlike ERM proteins that localize binding partners away from the immunologic synapse via its interaction with the actin cytoskeleton, 4.1R does not appear to move its binding partner LAT in order to regulate its phosphorylation. Instead, 4.1R colocalizes with LAT and ZAP-70 at the synapse. These results show that 4.1R and ERM proteins differ in the mechanism by which each links the actin cytoskeleton and signaling molecules downstream of the TCR. While the precise mechanism by which 4.1R mediates the inhibition of LAT phosphorylation by ZAP-70 remains to be determined, Kang et al contribute to our broader understanding of how actin cytoskeletal regulators can affect T-cell signaling and function.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal