Abstract

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) additionally elicits a whole array of pro-angiogenic responses, such as differentiation, proliferation, and migration. In this study, we demonstrate that in endothelial cells uPA also protects against apoptosis by transcriptional up-regulation and partially by mRNA stabilization of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins, most prominently the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). The antiapoptotic activity of uPA was dependent on its protease activity, the presence of uPA receptor (uPAR) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP), but independent of the phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase pathway, whereas vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–induced antiapoptosis was PI3 kinase dependent. uPA-induced cell survival involved phosphorylation of p21-activated kinase 1 (Pak1) and the IκB kinase α that leads to nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) p52 activation. Indeed, blocking NF-κB activation by using specific NF-κB inhibitors abolished uPA-induced cell survival as it blocked uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation. Furthermore, down-regulating XIAP expression by small interfering RNA (siRNA) significantly reduced uPA-dependent endothelial cell survival. This mechanism is also important for VEGF-induced antiapoptosis because VEGF-dependent up-regulation of XIAP was found defective in uPA−/− endothelial cells. This led us to conclude that uPA is part of a novel NF-κB–dependent cell survival pathway.

Introduction

During angiogenesis, endothelial cells emigrate from their residential site, lose cell-cell contacts, and focus cell-surface proteases to the leading edge to degrade the cellular matrix. These initial steps of angiogenesis (endothelial cell migration and invasion) exhibit a vulnerable phase for endothelial cells to become apoptotic resulting from the loss of the engagement of adhesion receptors. To guarantee cell survival during these initial steps of angiogenesis, several antiapoptotic mechanisms are operative: (1) Growth factors, such as the predominant angiogenic growth factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), cause antiapoptosis of endothelial cells by activating the antiapoptotic kinase Akt/protein kinase B via a phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3)–kinase–dependent mechanism. Long-term antiapoptotic effects of VEGF are in addition mediated through the transcriptional up-regulation of the antiapoptotic genes Bcl-2 and A1.1 (2) During the “angiogenic switch,” the broad substrate specific integrins β3 and β5 are expressed, ensuring adhesion also to novel matrices to which invading endothelial cells become exposed. This mechanism provides adhesion-dependent signal transduction leading to activation of kinases, such as focol adhesion kinase (FAK) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) as well as to cell survival.2,3

We have shown previously that the urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA)/uPA receptor (uPAR)/plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) system is linked to endothelial cell migration.4 Thereby pro-uPA is activated and uPAR is internalized and redistributed to the leading edge of migrating cells. In this process, an initial deactivation of integrins is critically involved,5 causing impaired cell adhesion and in turn deficient adhesion-dependent antiapoptosis. We were therefore interested whether uPA generated from pro-uPA by VEGF5 possibly counteracts this impaired antiapoptosis. Such a mechanism would facilitate invasion of endothelial cells into foreign matrices.

Here, we describe a pathway by which uPA induces endothelial cell survival in an nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP)–dependent manner. The antiapoptotic activity of uPA was dependent on its proteolytic activity, the presence of the urokinase receptor, and interaction with an internalization receptor of the low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) family. This pathway seems also to be involved in VEGF-induced cell survival, as VEGF-induced up-regulation of XIAP was significantly diminished in uPA-deficient endothelial cells.

Methods

Cell culture, reagents, antibodies

Human endothelial cells (skin microvascular or umbilical vein origin) were cultured in M199 (Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien, Seelze, Germany) supplemented with 20% fetal calf serum and endothelial cell growth supplement (Technoclone, Vienna, Austria). Experiments were performed using subconfluent cultures up to passage 5, silenced under serum-reduced conditions for 4 or 24 hours, as indicated. Murine microvascular endothelial cells isolated from uterus of uPA−/− mice and from the respective wild-type controls were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Proteins were purchased as follows: recombinant human VEGF165, Promocell (Heidelberg, Germany); recombinant mouse VEGF164 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA); vitronectin, laminin, poly-D-lysine, and fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien); Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); and active uPA (EBEWE Pharmaceuticals, Unterach, Austria). The inhibitors PD098059 and LY294002 (Calbiochem), wortmannin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO), Bay11-7082 (BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA), benzamidine-hydrochloride (Bayer AG, Wuppertal, Germany), di-isopropylfluorophosphate (DFP; Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien), and the 4′-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole used for nuclear staining (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were obtained as indicated. The following antibodies were used for immunoblotting: anti-Akt and anti–phospho-S(473)-Akt (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), anti-IκB kinase alpha (IKKα) and anti-pIKK (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-IKKβ (Imgenex, San Diego, CA), anti–phospho-IKKα (Thr23; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), anti–phospho-IKKα (Ser180)/ IKKβ (Ser181) (Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Pak and anti–phospho-Pak (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA). The monoclonal mouse antibodies against uPAR R3 and R5 have previously been described.6 To account for nonspecific binding in all immunoassays, purified nonimmune mouse IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) or rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) was used. It was assured that all reagents used in cell culture were endotoxin free as revealed by negative results of limulus amebocyte lysate assay (Endochrome; Charles River Endosafe, Charleston, SC).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

The effectiveness of the growth factors on the respective signal transduction pathways and of inhibitors was analyzed in experiments determining the induced phosphorylation of specific target molecules by immunoblotting using standard procedures described by us.7,8 To assess activation of the NF-κB pathway, quiescent human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were left untreated or stimulated with either uPA or VEGF for 10 minutes and then lysed in ice-cold buffer containing 1% detergent, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM ris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail Complete (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). IKKα and IKKβ were subsequently precipitated from full cell lysate containing 500 μg of protein and inhibitors using beads conjugated with anti-IKKα or anti-IKKβ antibodies, respectively. Replicate amounts of lysate were incubated with beads equally conjugated with nonimmune IgG of identical isotype as the specific primary antibodies originating from corresponding species. Precipitated proteins were lysed in Laemmli buffer and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and developed subsequently with antibodies against phospho-IKKα (Thr23) or phospho-IKKα (Ser180)/IKKβ (Ser181). Thereafter membranes were reprobed and cross-reprobed for IKKα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and IKKβ, respectively. Quantification was performed with a respective software using values determined for the phospho and holo forms by chemiluminescent imaging with a FluorChem HD2 (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA).

Immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy

Stimulated or unstimulated cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes on ice and permeabilized with 0.2% Tween-20 in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 minutes at 37°C. Double immunostaining for p50/p52 or p50/p65 members of the NF-κB family was performed by overnight incubation at 4°C with the respective antibodies against NF-κBp52, NF-κBp65, and NF-κBp50 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a 1:500 dilution in antibody dilution buffer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Alexa Fluor 488– and Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)–labeled antibodies were used as secondary antibodies.

Slides were mounted in Permafluor (Lab Vision, Fremont, CA), images were visualized on a Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal system in multitrack mode, using pinhole sizes between 0.7 and 1.5 μm, and the appropriate standard laser-filter combinations with 100× magnification were recorded and analyzed with the Carl Zeiss Confocal Microscope (AIM) software (equipment and software from Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

Cell-survival assay

Human microvascular endothelial cells (HUMECs) were serum starved for 24 hours, before seeding at subconfluent density of 5000 attached cells per unit (5 × 8 mm) on adhesive matrix-coated plastic dishes in 1% serum. Two hours later, cultures were carefully washed twice to remove nonattached cells. Endothelial cells attached to the matrix were counted, and cell number per surface unit (40 mm2) was determined. Thereafter, serum-deprived endothelial cells were incubated with VEGF165 or uPA in the presence or absence of different substances as indicated. The number of attached endothelial cells per unit was again determined at the indicated time points. Replicate measurements were performed for each experiment as indicated.

Apoptosis assay

Involvement of XIAP in the uPA-mediated antiapoptosis was determined by silencing the gene of interest in endothelial cells using the SignalSilence XIAP siRNA Kit (Cell Signaling Technology) according to the instructions.

Apoptosis was examined by dUTP-X nick end labeling (TUNEL). Cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated dUTP according to the manufacturer's specifications (Roche Diagnostics), then counterstained with 10 μg/mL propidium iodide in the presence of 200 μg/mL RNase A, and collected on microscope slides by cytospin. Cells were visualized on an Olympus AX70 microscope (Tokyo, Japan), and digital images were recorded using an F-View camera. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells was evaluated with the software package AnalySiS Pro (Soft Imaging System, Münster, Germany).

Relative quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

As described previously,9 for isolation of RNA, TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was used. cDNA was generated from 900 ng of total RNA with murine leukemia virus (MuLV) reverse transcriptase using the Gene Amp RNA PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers were designed with PRIMER3 software from the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research (Cambridge, MA) using the reference mRNA sequences of respective genes from the GenBank.10 The following primers were used: for XIAP forward 5′-TTTGCCTTAGACAGGCCATC-3′, reverse 5′-TTTCCACCACAACAAAAGCA-3′; for BIRC2 (cIAP-1) forward 5′-AGCTAGTCTGGGATCCACCTC-3′, reverse 5′-GGGGTTAGTCCTCGATGAAG-3′; for BIRC3 (cIAP-2) forward 5′-TGGAAGCTACCTCTCAGCCTAC-3′, reverse 5′-GGAACTTCTCATCAAGGCAGA-3′; for BIRC5 (survivin) forward 5′-GGACCACCGCATCTCTACAT-3′, reverse 5′-GACAGAAAGGAAAGCGCAAC-3′; for PMiap3 forward 5′-TTGGAACATGGACATCCTCA-3′, reverse 5′-TGCCCCTTCTCATCCAATAG-3′. Primers for Porphobilinogen deaminase and β2-microglobulin were used as described by us previously.9 Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed by LightCycler technology using the Fast Start DNA Master Plus SYBR Green I Kit for amplification and detection (Roche Diagnostics) also as described.9 The reactions were performed using 3 μL DNA Master Mix Plus (containing 25 mM MgCl2), 10.1 μL H2O, 0.4 μL of each primer (10 μM), and cDNA corresponding to 2.5 ng of total RNA used for reverse transcription. Relative quantification of any investigated gene was calculated by normalization to a housekeeping gene using the mathematical model by Pfaffl11 and presented as fold variation over the unstimulated control.

mRNA stability

To measure mRNA stability of members of the IAP family, HUVECs were stimulated with 100 nM uPA or the vehicle for 6 hours. Thereafter 5 μg/mL actinomycin D was added, and samples were taken at different time points up to 12 hours after actinomycin D addition for preparation of mRNA. mRNA of members of the IAP family were quantified in these samples by quantitative polymerase chain reaction as described in “Methods,” and mRNA decay constants (Kd) as well as mRNA half-life were calculated according to Ross.12

Statistics

Statistical significance was analyzed by paired or unpaired t test when one group was compared with the control group. To compare 2 or more groups with the control group, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett tests as posttests were used. Significance was assigned to P values of less than .01.

Results

uPA causes endothelial cell survival

uPA is known to play a prominent role in angiogenesis.13 When endothelial cells are activated by proangiogenic stimuli, such as VEGF165, pro-uPA is activated, and its expression is increased.5,14 Active uPA then initiates proteolysis and induces in an autocrine and in a paracrine fashion intracellular signal transduction, thereby promoting cell migration. Whether uPA also mediates cell survival in endothelial cells, an important prerequisite for endothelial cells to effectively invade surrounding matrix, is unknown.

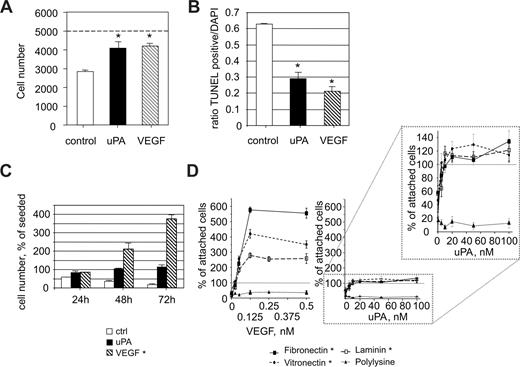

In an initial set of experiments, we analyzed potential antiapoptotic activities of uPA (Figure 1A). Endothelial cells were seeded on vitronectin in a density of 5000 attached cells per unit (40 mm2) under serum-reduced conditions (1% serum). The number of cells recovered after 24 hours was 58.2% plus or minus 1.7%. When, however, uPA (100 nM) was present, the number of cells recovered was almost equal to the number of initially attached cells. Similar results were found when uPA was replaced by VEGF165 (1.25 nM). This indicates that uPA as well as VEGF165 either induce cell survival or cell proliferation or both. To address this question, we performed apoptosis assays (Figure 1B) using conditions as in Figure 1A. The presence of uPA significantly (P < .01) reduced the total number of apoptotic cells. At the concentrations used, VEGF165 and uPA had comparable (P > .1) effects in terms of reducing apoptosis (VEGF165, 23.4% ± 4.2% TUNEL-positive cells; uPA, 33.7% ± 2.8% TUNEL positive cells, both P < .01 compared with the control 63.4% ± 1.2%). To delineate whether uPA causes also endothelial cell proliferation, we analyzed cell numbers at later time points. Although, as expected, VEGF165 induced a significant increase in the total number of endothelial cells in a time-dependent manner, in the presence of uPA, the maximal number of endothelial cells recovered was comparable with the number of endothelial cells initially attached (Figure 1C). From these data, we conclude that, in contrast to the known mitogenic activity of VEGF165, uPA has almost no effect on endothelial cell proliferation but mediates cell survival under serum-reduced conditions.

uPA promotes endothelial cell survival. (A) HUMECs recovered after 24 hours from cultures seeded subconfluently on vitronectin (5000) under control conditions (2820 ± 45) or in the presence of uPA (100 nM; 4090 ± 345) or of VEGF165 (1.25 nM; 4210 ± 130). A reduction in cell number was found under serum reduced conditions that was prevented by uPA or VEGF165 (*P < .01 vs control; n = 3). (B) Percentage of apoptotic HUMECs seeded on vitronectin for 24 hours under control conditions or in the presence of uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). Both uPA and VEGF165 significantly reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells (*P < .01; n = 4). (C) Time course of recovered endothelial cells seeded on vitronectin in the absence or presence of uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). A significant increase was seen only in the presence of VEGF165 (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (D) Dose dependency of the effects of uPA or VEGF165 on the number of endothelial cells recovered 96 hours after seeding on different matrices in percentage of attached cells (2 hours after seeding). The effects of both uPA and VEGF165 were dependent on the presence of an adhesive matrix (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3).

uPA promotes endothelial cell survival. (A) HUMECs recovered after 24 hours from cultures seeded subconfluently on vitronectin (5000) under control conditions (2820 ± 45) or in the presence of uPA (100 nM; 4090 ± 345) or of VEGF165 (1.25 nM; 4210 ± 130). A reduction in cell number was found under serum reduced conditions that was prevented by uPA or VEGF165 (*P < .01 vs control; n = 3). (B) Percentage of apoptotic HUMECs seeded on vitronectin for 24 hours under control conditions or in the presence of uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). Both uPA and VEGF165 significantly reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells (*P < .01; n = 4). (C) Time course of recovered endothelial cells seeded on vitronectin in the absence or presence of uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). A significant increase was seen only in the presence of VEGF165 (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (D) Dose dependency of the effects of uPA or VEGF165 on the number of endothelial cells recovered 96 hours after seeding on different matrices in percentage of attached cells (2 hours after seeding). The effects of both uPA and VEGF165 were dependent on the presence of an adhesive matrix (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3).

This effect of uPA on cell survival was seen on endothelial cells attached to vitronectin, a matrix directly influencing the uPA/uPAR/PAI-1 system. To evaluate whether uPA is effective also on other matrices, we seeded endothelial cells on different matrix proteins and analyzed the effects of VEGF165 or uPA on the number of recovered cells. As seen in Figure 1D, uPA at concentrations from 5 to 10 nM onward led to survival of endothelial cells seeded on adhesive matrix proteins. The effect of VEGF165 on endothelial cell number recovered after 96 hours was also dose and matrix dependent, starting at concentrations as low as 0.063 nM. VEGF165, however, also induced cell proliferation on fibronectin, vitronectin, or laminin. Neither uPA nor VEGF165 had any significant effect on cell proliferation or cell survival when cells were seeded on poly-D-lysine, indicating the requirement of engaged integrin adhesion receptors. From these data, we conclude that uPA strongly supports endothelial cell survival but not proliferation in a cell-adhesion matrix-dependent fashion.

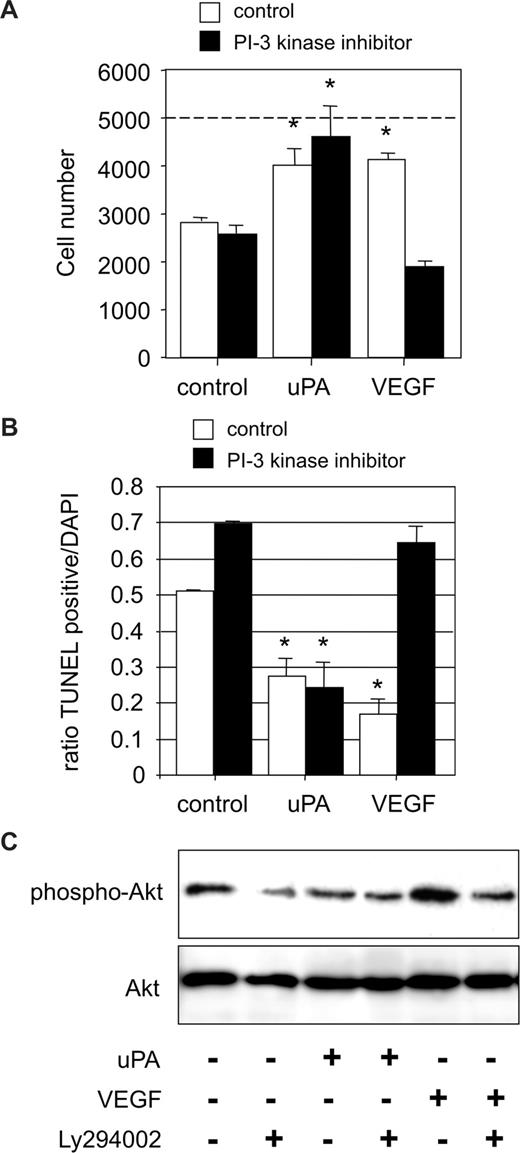

uPA causes endothelial cell survival independent of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway

VEGF165 mediates via VEGFR-2 endothelial cell survival in a PI3 kinase/Akt-dependent manner.15,16 Thereby, Akt/protein kinase B, as a central regulator of mitochondrial apoptosis, activates several antiapoptotic pathways. Consequently, we determined the involvement of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway in uPA-mediated endothelial cell survival. uPA-induced cell survival remained unaffected in the presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002. In contrast, endothelial cell numbers recovered after 24 hours of VEGF165 stimulation in the presence of Ly294002 were significantly lower as in the absence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor (Figure 2A). Further apoptosis assays confirmed that uPA-mediated cell survival was independent of active PI3 kinase. In contrast, VEGF165-induced antiapoptosis was almost completely dependent on PI3 kinase (Figure 2B). Finally, we analyzed activation of Akt by uPA or VEGF165, using antibodies specific for phosphorylated serine 473 Akt. VEGF165 induced phosphorylation of Akt in a PI3 kinase–dependent manner,15 whereas uPA was ineffective with respect to Akt phosphorylation (Figure 2C). From these data, we conclude that uPA causes endothelial cell survival, independent of the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway.

uPA-dependent cell survival is PI3 kinase independent. (A) HUMECs recovered after 24 hours from cultures seeded subconfluently on vitronectin (5000) in the absence or presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) and treated with either uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). The effect of uPA was independent of the presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor (*P < .01 vs control; n = 3). (B) Percentage of apoptotic HUMECs seeded on vitronectin for 24 hours in the absence or presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) and treated with either uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). The effect of uPA in reducing the percentage of apoptotic cells was independent of the presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor (*P < .01; n = 3). (C) Representative Western blot for pSer473 Akt in endothelial cells treated with uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM) and in the absence or presence of the specific PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM). uPA did not induce Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt after 10 minutes (n = 3).

uPA-dependent cell survival is PI3 kinase independent. (A) HUMECs recovered after 24 hours from cultures seeded subconfluently on vitronectin (5000) in the absence or presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) and treated with either uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). The effect of uPA was independent of the presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor (*P < .01 vs control; n = 3). (B) Percentage of apoptotic HUMECs seeded on vitronectin for 24 hours in the absence or presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) and treated with either uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). The effect of uPA in reducing the percentage of apoptotic cells was independent of the presence of the PI3 kinase inhibitor (*P < .01; n = 3). (C) Representative Western blot for pSer473 Akt in endothelial cells treated with uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM) and in the absence or presence of the specific PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM). uPA did not induce Ser473 phosphorylation of Akt after 10 minutes (n = 3).

uPA mediates endothelial cell survival via NF-κB–dependent XIAP gene expression

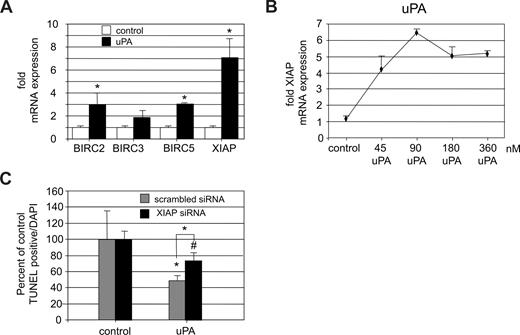

In addition to the mitochondrial pathway that affects cell survival, the family of inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) has been shown to play an essential role in survival of endothelial cells.17,18 Their activity is mainly regulated on the transcriptional level. Our findings suggested that uPA-mediated cell survival is independent of the PI3 kinase/Akt–induced antiapoptotic pathways. We therefore analyzed a possible regulation of IAPs by uPA. When serum-starved endothelial cells were stimulated by uPA, the expression of BIRC2, BIRC5 (survivin), and most prominently the X-linked IAP (XIAP/BIRC4) genes was significantly increased (Figure 3A). Thereby, the effect of uPA on up-regulation of XIAP expression was dose dependent (Figure 3B). XIAP has been shown by us to mediate antiapoptosis in endothelial cells under inflammatory conditions.17

uPA induces up-regulation of XIAP. (A) Up-regulation of different IAP protein mRNAs in HUVECs on treatment with uPA (100 nM) for 6 hours presented as fold expression over unstimulated control. uPA induced a significant increase of IAPs, most prominently the XIAP (*P < .01; n = 4). (B) Dose-dependent effect of uPA (6 hours) on XIAP mRNA expression in HUVECs. Data represent fold increase over control (P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (C) Effect of down-regulation of XIAP by siRNA to approximately 35% of control levels on the effect of uPA on the percentage of apoptotic cells. In scrambled siRNA-treated endothelial cells, uPA reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells to approximately half, whereas in specific XIAP siRNA-treated cells, the effect of uPA was significantly smaller (∼ 25%) and not significantly different from control. XIAP down-regulation induced an increase in apoptosis by 2.9-fold compared with scrambled control in untreated endothelial cells (not shown; *P < .01, #P > .05; n = 3).

uPA induces up-regulation of XIAP. (A) Up-regulation of different IAP protein mRNAs in HUVECs on treatment with uPA (100 nM) for 6 hours presented as fold expression over unstimulated control. uPA induced a significant increase of IAPs, most prominently the XIAP (*P < .01; n = 4). (B) Dose-dependent effect of uPA (6 hours) on XIAP mRNA expression in HUVECs. Data represent fold increase over control (P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (C) Effect of down-regulation of XIAP by siRNA to approximately 35% of control levels on the effect of uPA on the percentage of apoptotic cells. In scrambled siRNA-treated endothelial cells, uPA reduced the percentage of apoptotic cells to approximately half, whereas in specific XIAP siRNA-treated cells, the effect of uPA was significantly smaller (∼ 25%) and not significantly different from control. XIAP down-regulation induced an increase in apoptosis by 2.9-fold compared with scrambled control in untreated endothelial cells (not shown; *P < .01, #P > .05; n = 3).

The increase in IAP mRNA levels on uPA stimulation can be a result of increased mRNA synthesis or its stabilization. To address this question, we performed experiments similar to the ones shown in Figure 3A, but adding actinomycin D at different time points before or after adding uPA or the vehicle. Addition of actinomycin D significantly reduced the increase in XIAP mRNA levels 6 hours after uPA addition to approximately 30% of the XIAP mRNA increase induced by uPA in the absence of actinomycin D (P < .01), indicating that the majority of uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation is a result of increased XIAP mRNA synthesis. Consistent with the approximately 30% remaining increase in XIAP mRNA on uPA stimulation in the presence of actinomycin D, XIAP mRNA stability increased in the presence of uPA from 3.4 to 10.1 hours (Kd decreased from −0.20252 in the absence to −0.06827 in the presence of uPA). mRNA stability of the other IAP members either increased slightly on uPA stimulation (BIRC2 from 3.9-5.4 hours; BIRC3 from 5.1-7.9 hours) or decreased (BIRC5 from 11.7-5.0 hours). These data indicate that the increase in XIAP mRNA levels on uPA stimulation is mainly a result of mRNA synthesis but partially also to increased mRNA stability.

To confirm the functional role of XIAP in uPA-mediated endothelial cell survival, we down-regulated XIAP expression in endothelial cells to approximately 35% by small interfering RNA and analyzed the effect of uPA on apoptosis (Figure 3C). uPA had only a minimal and not significant antiapoptotic effect in XIAP siRNA-treated cells (74.25% ± 10.05%, P = .24). Mock-transfected endothelial cells showed a significant reduction in cell death on uPA stimulation to 48.8% plus or minus 5.6% (P < .01). From these data, we conclude that uPA induces survival of endothelial cells in a mainly XIAP-dependent fashion.

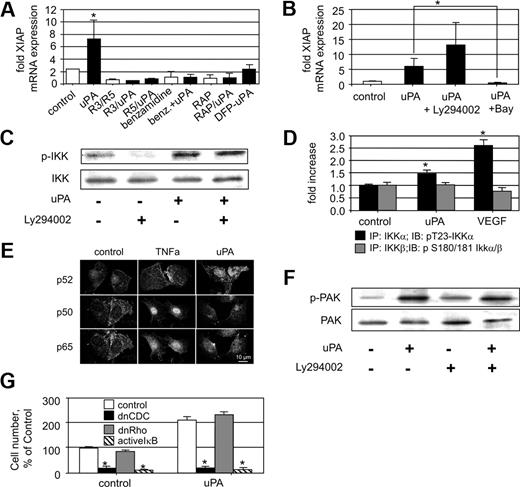

uPA induces XIAP up-regulation dependent on active uPA, its receptor uPAR, a member of the LDLR family, and the NF-κB pathway

uPA interacts with cells via its specific receptor uPAR, which mediates intracellular signal transduction; one pathway of uPAR-induced cell signaling involves interaction with members of the LDLR family. Therefore, we were interested which compound of the uPA/uPAR signalosome19 is involved in uPA-induced XIAP regulation. Using a monoclonal antibody that competes with uPA binding to uPAR (mAB R3) as well as another monoclonal noncompetitive inhibitory antibody (mAB R5) both directed against different epitopes on domain I of uPAR,6 we found that uPA/uPAR interaction is essential for up-regulation of XIAP by uPA because both antibodies inhibited this uPA effect. Furthermore, we could demonstrate that uPA has to be active to induce XIAP up-regulation because the serine protease inhibitor benzamidine blocked the uPA effect and DFP-treated uPA was ineffective (Figure 4A). In addition, whenever the chaperone receptor-associated protein, which inhibits ligand binding to LDLR family members, was present, uPA was also ineffective in terms of XIAP up-regulation. From these data, we conclude that active uPA mediates XIAP up-regulation by a mechanism involving uPAR and a member of the LDLR family.

uPA-induced XIAP mRNA up-regulation is dependent on the NF-κB pathway. (A) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUMECs by uPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of monoclonal antibodies inhibiting uPA-uPAR interaction (mAB R3, mAB R5; 10 μg/mL), benzamidine (100 μM), which inhibits uPA serine protease activity, or the LRP chaperone receptor-associated protein (200 nM), or by DFP-inactivated uPA (100 nM). uPA up-regulation of XIAP is dependent on uPAR, active uPA, and a member of the LDLR family (*P < .01; n = 4). (B) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUMECs by uPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM) or the specific IKK inhibitor BAY11-7085 (5 μM). uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation is Ly294002 independent but BAY11-7085 dependent (*P < .01; n = 3). (C) Effect of uPA (100 nM) on phosphorylation of IKK in HUMECs in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM). Phosphorylation of IKK by uPA is Ly294002 independent (one representative Western blot is shown; n = 3). (D) Quantification of phospho-IKKs in immunoprecipitates obtained with mAbs against IKKα or IKKβ from HUVECs stimulated with uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). uPA as well as VEGF165 induces phosphorylation of IKKα but not of IKKβ (P < .01; n = 3). (E) Demonstration of the nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits in endothelial cells induced by either 100 nM uPA or 10 nM TNF-α. Confocal laser micrographs are shown for endothelial cells stimulated by vehicle control or TNF-α, or uPA for 60 minutes. One representative picture of 3 independent experiments is shown. Bar represents 10 μm. (F) Pak1 phosphorylation in HUMECs on uPA (100 nM) treatment in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM). Phosphorylation of Pak1 by uPA is Ly294002 independent (one representative Western blot is shown; n = 3). (G) Number or recovered HUMECs 72 hours after seeding in percentage of control. HUMECs were either untreated (left panel) or treated with uPA (100 nM; right panel). HUMECs were transfected with either empty vector (control) or a retrovirus carrying dnCdc42 or dnRho GTPase or an adenovirus carrying IκB (*P < .01 vs respective control; n = 3).

uPA-induced XIAP mRNA up-regulation is dependent on the NF-κB pathway. (A) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUMECs by uPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of monoclonal antibodies inhibiting uPA-uPAR interaction (mAB R3, mAB R5; 10 μg/mL), benzamidine (100 μM), which inhibits uPA serine protease activity, or the LRP chaperone receptor-associated protein (200 nM), or by DFP-inactivated uPA (100 nM). uPA up-regulation of XIAP is dependent on uPAR, active uPA, and a member of the LDLR family (*P < .01; n = 4). (B) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUMECs by uPA (100 nM) in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM) or the specific IKK inhibitor BAY11-7085 (5 μM). uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation is Ly294002 independent but BAY11-7085 dependent (*P < .01; n = 3). (C) Effect of uPA (100 nM) on phosphorylation of IKK in HUMECs in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM). Phosphorylation of IKK by uPA is Ly294002 independent (one representative Western blot is shown; n = 3). (D) Quantification of phospho-IKKs in immunoprecipitates obtained with mAbs against IKKα or IKKβ from HUVECs stimulated with uPA (100 nM) or VEGF165 (1.25 nM). uPA as well as VEGF165 induces phosphorylation of IKKα but not of IKKβ (P < .01; n = 3). (E) Demonstration of the nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits in endothelial cells induced by either 100 nM uPA or 10 nM TNF-α. Confocal laser micrographs are shown for endothelial cells stimulated by vehicle control or TNF-α, or uPA for 60 minutes. One representative picture of 3 independent experiments is shown. Bar represents 10 μm. (F) Pak1 phosphorylation in HUMECs on uPA (100 nM) treatment in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor Ly294002 (10 μM). Phosphorylation of Pak1 by uPA is Ly294002 independent (one representative Western blot is shown; n = 3). (G) Number or recovered HUMECs 72 hours after seeding in percentage of control. HUMECs were either untreated (left panel) or treated with uPA (100 nM; right panel). HUMECs were transfected with either empty vector (control) or a retrovirus carrying dnCdc42 or dnRho GTPase or an adenovirus carrying IκB (*P < .01 vs respective control; n = 3).

XIAP expression is mainly regulated by NF-κB.17,20 To test the role of NF-κB in uPA-induced XIAP regulation, we used the specific NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7082, a compound that prevents IκB phosphorylation. Using this inhibitor, the uPA effect on XIAP expression was completely blocked (Figure 4B). In concordance with these findings, inhibition of PI3 kinase by the synthetic inhibitor Ly294002 had no inhibitory effect on uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation.

NF-κB is activated by phosphorylation of IκB mediated by IKKs. Therefore, we analyzed activation of IKKs on uPA stimulation using a phospho-IKK specific antibody. When endothelial cells were stimulated with uPA, IKK became phosphorylated within 10 minutes. Again, uPA-induced phosphorylation of IKK was PI3 kinase independent (Figure 4C). To differentiate between a possible specific effect on IKKα or IKKβ, we analyzed phosphorylation of IKKα at T-23 and IKKβ at S-181 in immunoprecipitates of IKKα or IKKβ from lysates of endothelial cells stimulated for 10 minutes with either uPA or VEGF165. Whereas IKKβ phosphorylation remained unaffected (Figure 4D), T-23 phosphorylation of IKKα21 was increased on uPA as well as VEGF165 stimulation. This suggests that uPA induces NF-κB activation via IKKα. Consistently,22 the NF-κB subunit translocated into the nucleus on uPA stimulation (100 nM for 15, 30, and 60 minutes) was predominantly the p52 subunit, whereas on tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stimulation (10 nM for 15, 30, and 60 minutes), p50 and p65 became translocated into the nucleus (Figure 4E).

To further track the signaling pathway induced by uPA leading to IKKα phosphorylation, we analyzed phosphorylation of p21-activated kinase (Pak1), a serine/threonine protein kinase whose activity is stimulated by binding of the small Rho GTPase Cdc42. In contrast to endotoxin-induced NF-κB activation, growth factors such as VEGF165 or cytokines such as TNF-α induce activation of small Rho-GTPases, which themselves induce Pak1 auto-phosphorylation and activation. Pak1 has been reported to be required as an upstream factor for activation of NF-κB, and active Pak1 stimulates NF-κB activity.23 When the effect of uPA on Pak1 phosphorylation was determined, we found that uPA indeed induced Pak1 phosphorylation in a PI3 kinase–independent manner (Figure 4F). Cdc42 is an upstream regulator of Pak1 phosphorylation. In cells overexpressing a dominant-negative (dn) form of Cdc42 (dnCdc42), uPA was ineffective in preventing endothelial cell apoptosis (Figure 4G), whereas a dnRho GTPase had no effect. Consistent with the involvement of the NF-κB pathway in uPA-induced XIAP up-regulation, the uPA effect on cell survival was inhibited by adenoviral-mediated IκB overexpression.24

From these data, we conclude that active uPA via uPAR and a member of the LDLR family activates key components of the NF-κB pathway such as Pak1 and IKKα, which leads to activation of NF-κB p52 and in turn up-regulation of IAPs.

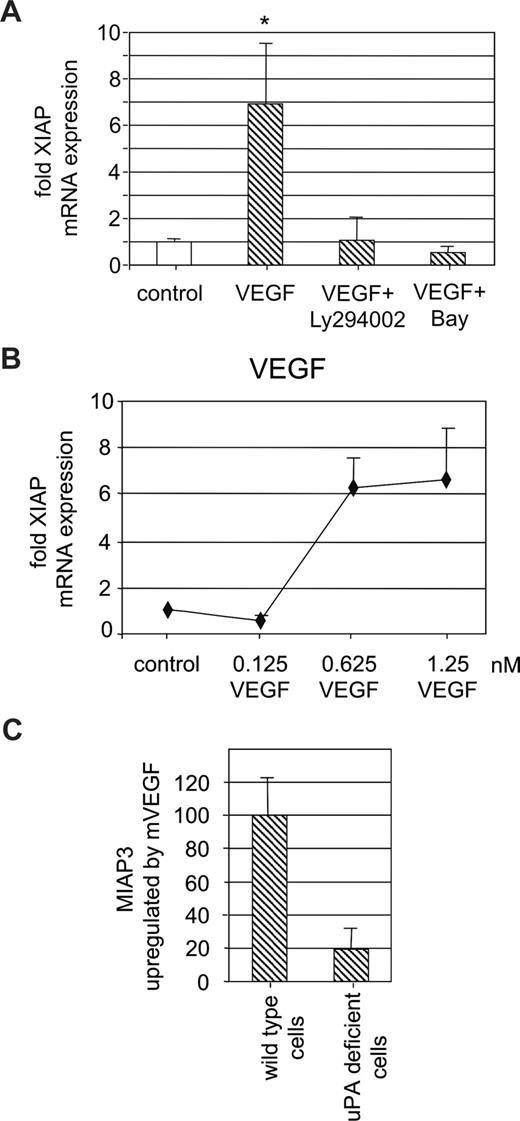

uPA participates in VEGF-induced XIAP up-regulation

We have previously shown that in endothelial cells pro-uPA is activated on VEGF165 stimulation.5 Therefore, we wanted to analyze whether VEGF165-induced uPA activation also contributes to endothelial cell survival. When we determined XIAP expression on VEGF165 stimulation in serum-starved endothelial cells, we could show XIAP up-regulation by VEGF165 in a dose-dependent fashion consistent with a previous report by others25 (Figure 5A). VEGF165-induced XIAP up-regulation was dependent on PI3 kinase and NF-κB because the respective inhibitors Ly294002 and BAY 11-7082 abolished the VEGF165 effect on XIAP expression (Figure 5B). From these data, we conclude that VEGF165 induces XIAP expression in an NF-κB–dependent fashion, which, in contrast to uPA, is also PI3 kinase dependent. To determine whether such VEGF-induced XIAP up-regulation is dependent on uPA, we used endothelial cells derived from uPA−/− mice or respective wild-type animals. When such uPA-deficient endothelial cells were stimulated with recombinant mouse VEGF164, miap3 (the murine homologue of human X-linked IAP) mRNA expression did not change, whereas in control endothelial cells derived from wild-type mice VEGF164 induced a significant increase in miap-3 mRNA (Figure 5C).

VEGF-induced XIAP mRNA up-regulation is uPA dependent. (A) Dose-dependent effect of VEGF165 (6 hours) on XIAP mRNA expression in HUVECs. Data represent fold increase over control (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (B) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUVECs by VEGF165 (1.25 nM) in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) or the specific IKK inhibitor BAY 11-7085 (5 μM). XIAP up-regulation by VEGF165 is dependent on LY294002 and BAY 11-7085 (P < .01; n = 4). (C) miap3 (the mouse homolog of XIAP) mRNA up-regulation by mVEGF164 (1.25 nM) in wild-type or uPA−/− mouse endothelial cells. Data are shown as ratio of miap3 mRNA in VEGF-treated uPA−/− cells over miap3 mRNA in VEGF-treated wild-type control cells. VEGF induced up-regulation of miap3 mRNA is only approximately one-fifth in uPA-deficient cells (P < .01; n = 3).

VEGF-induced XIAP mRNA up-regulation is uPA dependent. (A) Dose-dependent effect of VEGF165 (6 hours) on XIAP mRNA expression in HUVECs. Data represent fold increase over control (*P < .01, ANOVA; n = 3). (B) XIAP mRNA up-regulation in HUVECs by VEGF165 (1.25 nM) in the absence or presence of the specific PI3 kinase inhibitor LY294002 (10 μM) or the specific IKK inhibitor BAY 11-7085 (5 μM). XIAP up-regulation by VEGF165 is dependent on LY294002 and BAY 11-7085 (P < .01; n = 4). (C) miap3 (the mouse homolog of XIAP) mRNA up-regulation by mVEGF164 (1.25 nM) in wild-type or uPA−/− mouse endothelial cells. Data are shown as ratio of miap3 mRNA in VEGF-treated uPA−/− cells over miap3 mRNA in VEGF-treated wild-type control cells. VEGF induced up-regulation of miap3 mRNA is only approximately one-fifth in uPA-deficient cells (P < .01; n = 3).

From these data, we conclude that uPA participates significantly in VEGF164-induced miap-3 up-regulation in endothelial cells, thus providing an additional mechanism for VEGF-dependent endothelial cell survival.

Discussion

The interaction of uPA with uPAR mediates several proangiogenic responses in endothelial cells, including chemotactic activation, cell migration, proliferation, and cell differentiation. We now added to this list of uPA induced endothelial cell responses19 antiapoptosis. Antiapoptosis is an important mechanism in angiogenesis because during cell migration cells are exceptionally susceptible to apoptosis. Antiapoptosis induced by uPA in endothelial cells is also clearly dependent on the presence of adhesive matrices because this uPA effect is prevented when cells are seeded on the nonadhesive matrix poly-D-lysine. This adhesive matrix dependency of uPA is similar to the dependency of VEGF effects on endothelial cell proliferation and antiapoptosis and indicates the prerequisite of endothelial cells being attached to the matrix to respond to VEGF as well as to uPA. However, the matrix dependency for both VEGF and uPA is clearly not restricted to a specific extracellular matrix protein because it is operative on a variety of matrix proteins, including those toward that an invading and migrating endothelial cell could become exposed when leaving the specific vascular basement membrane.

The variety of cellular responses induced by uPAR/uPA is mediated by several intracellular signaling pathways including ERK1/2, G-protein coupled receptors, small GTP-binding proteins, and STAT signaling. We now describe an additional intracellular signaling pathway induced by uPA, namely, NF-κB activation. This urokinase-induced pathway is dependent on interaction of uPA with uPAR and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP)–like molecules and leads to phosphorylation of Pak1 and IKKα, independent of the PI3 kinase pathway. Because IKKβ phosphorylation remained unchanged, our data also indicate that uPA activation of NF-κB is different from the inflammatory activation that occurs mainly via activation of IKKβ. This difference is also demonstrated by the finding that uPA induces nuclear translocation of p52, whereas TNF-α acts the opposite inducing the classic NF-κB pathway and nuclear translocation of p65 but not of p52. This is important because IKKα-dependent activation of NF-κB seems to generate a different response compared with inflammatory activation of IKKβ. These differences are reflected by the phenotype of IKKα-deficient mice, which present with multiple morphogenetic defects, including limb, skin, and skeletal patterning,26 whereas IKKβ deficiency results in early embryonic lethality.26,27 IKKα activation by uPA involves most probably Cdc42 and Pak1 activation, whereby TAB and TAK would link to phosphorylation of IKK.20 Although we have not directly shown here that uPA activates Cdc42, the finding shown in Figure 4F indicates that Cdc42 is involved in the uPA-induced antiapoptosis pathway. Cdc42 is activated through PI3 kinase/Akt28 or through the p130Cas/Crk/DOCK180 signaling complex.29 This implicit pathway is consistent with published data on uPAR/uPA-induced activation of Rho-GTPases via integrins.30

The antiapoptotic effect of uPA is mediated by up-regulation of IAPs. We have shown previously that XIAP is responsible for endothelial cell survival under inflammatory conditions,17 and we now can demonstrate that XIAP also mediates uPA-dependent antiapoptosis. This was shown by up-regulation of IAP proteins in response to uPA and by XIAP siRNA experiments. In these experiments, partial inhibition of XIAP up-regulation decreased the antiapoptotic effect of uPA. Still, some antiapoptotic activity of uPA remained, which might be a result of either remaining XIAP expression or to up-regulation of other IAP proteins (Figure 3A,C). In addition to up-regulation of mRNA of IAP proteins, uPA also increases mRNA stability of XIAP, BIRC2, and BIRC3, thereby contributing to increased mRNA levels of these members of the IAP family.

Angiogenic cell migration and concomitant exposure of endothelial cells toward a novel matrix are predominantly induced by VEGF. The antiapoptotic effects of VEGF is largely mediated via PI3 kinase/Akt, which induces PED/PEA-15 phosphorylation and stabilization of their antiapoptotic action,31 phosphorylation of caspase-9, which inhibits its proteolytic activity,32 as well as phosphorylation and inhibition of Bad, which, in its active form, induces apoptosis by inhibiting members of the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family.33 We here show that, in addition to a mitochondrial-dependent antiapoptotic pathway not analyzed in this report, VEGF165 also induces XIAP up-regulation. However, this pathway is Akt-dependent as well as NF-κB–dependent consistent with the dependency of VEGF-induced pro-uPA activation as shown by us previously.5 Our data demonstrating that VEGF165-induced XIAP up-regulation is defective in uPA-deficient endothelial cells indicate that VEGF165-induced uPA-activation is involved in VEGF165-dependent XIAP up-regulation. This pathway would involve PI3 kinase-dependent activation of pro-uPA and uPA-induced NF-κB activation and in turn XIAP up-regulation. This autocrine loop could amplify the endogenous antiapoptotic effect of VEGF mediated by the mitochondrial pathways and would further point toward a possible additional paracrine proangiogenic activity of uPA secreted by, for example, tumor cells. Such tumor cells could induce angiogenic activation via secreted VEGF and provide additional antiapoptotic mechanisms via secretion and activation of uPA. There is ample evidence that uPA expressed by tumors supports angiogenesis34-36 and, although speculative, data reported here could further strengthen this notion.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The retroviral constructs expressing dnCdc42 and dnRho were a kind gift of A. J. Ridley, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Royal Free and University College School of Medicine, London, United Kingdom.

This work was supported by the Hans and Blanca Moser Foundation, Initiative Krebsforschung (UE71104011) and the Integrated Project of the 6th European Union (EU) framework program Cancerdegradome (contract no. LSHC-CT-2003-503297).

The authors of this manuscript belong to the European Vascular Genomics Network (http://www.evgn.org), a Network of Excellence supported by the European Community's sixth Framework Program for Research Priority 1 “Life sciences, genomics and biotechnology for health” (contract no. LSHM-CT-2003-503254).

Authorship

Contribution: G.W.P., J.M., P.M.B., and Y.K. performed experiments; G.H.-H. analyzed results; and G.W.P. and B.R.B. designed the research and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Bernd R. Binder, Schwarzspanier Str 17, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; e-mail: bernd.binder@meduniwien.ac.at.