Abstract

Whether advances in treatment are prolonging survival of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is unclear. We analyzed presentation patterns and survival over time in 929 patients followed from 1980 to 2008 at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona. The 5- and 10-year relative survival (adjusted for the expected survival in the general population) was estimated in patients seen in 2 periods of time: 1980-1994 (n = 451) and 1995-2004 (n = 365). We found that CLL shortens life expectancy in all age groups independently of clinical features at diagnosis. Nevertheless, survival is improving, particularly in some groups of patients. Thus, relative survival was significantly higher in the 1995-2004 cohort than in the 1980-1994 group both at 5 years (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 0.46; P = .004) and 10 years (IRR = 0.65; P = .007) from diagnosis. The improved survival was largely due to a decrease in CLL-attributable mortality in patients younger than 70 years in Binet stage B or C at diagnosis (IRR = 0.40; P = .001 at 5 years; IRR = 0.33; P < .001 at 10 years). These results suggest that newer treatments are changing the prognosis of CLL, particularly in younger patients with advanced disease, whereas no improvement is yet observed in older subjects or those with lower-risk disease.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a frequent malignancy composed of CD5+ B lymphocytes, is predominant in older people, and has a variable clinical course. The median survival of patients with CLL is approximately 10 years, but the individual prognosis is extremely variable. Whereas in some patients the disease runs an indolent clinical course and their life span is not shortened, in others the disease has an aggressive behavior with a survival of less than 2 to 3 years.1,2

Management of patients with CLL is one of the most challenging situations in hemato-oncology. For decades treatment of this disease revolved around the use of alkylating agents with little or no effect on the natural history of the disease. The introduction in the late 1980s of purine analogs signified an important breakthrough in the management of CLL. More recently, chemoimmunotherapy has emerged as the new paradigm for therapy of CLL.3-5

Whether new treatments, along with better general medical care, improve survival of patients with CLL is not completely clear. The analysis of historical series suggests a better survival for patients treated with modern therapies, but these analyses are biased by different median follow-up times and do not take into consideration the natural increase in the life expectancy of the general population.4-7 In addition, recent randomized studies have shown a longer progression-free, but not a longer overall, survival in patients receiving newer treatments.8,9 Yet the advantage of a given therapy over another in randomized studies, taking overall survival as end point, is difficult to establish because of the effect on patients' outcome of subsequent, rescue treatments. Finally, data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program of the US National Cancer Institute (www.seer.cancer.gov) indicate that there is a survival improvement in those patients most recently diagnosed, with the only exception of the elderly.10 However, registry studies have some limitations, such as underreporting and late reporting, which makes it difficult to ascertain recent progress in survival.11

The analysis of large series of patients from single institutions offers an important opportunity to investigate recent changes in the prognosis and survival patterns of CLL. The aim of this study was to investigate presentation features and survival over the time in a large series of patients with CLL seen at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona.

Methods

Patients

In total, 929 patients diagnosed with CLL between January 1980 and December 2008 and followed at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona were evaluated. All patients were diagnosed in agreement with the National Cancer Institute-Working Group Criteria.12 In addition by excluding patients diagnosed before 1980 we assured that diagnosis was confirmed by flow cytometry in all patients. Demographic characteristics and clinical and laboratory features at presentation, as well as treatment methods and follow-up data, were obtained from a database that has been prospectively managed from the 1970s onward.

Study design

Changes in prognosis over the time were investigated by comparing the relative survival and disease-specific incidence mortality between 451 patients diagnosed from 1980 to 1994 and 365 patients diagnosed from 1995 to 2004. We limited the year of diagnosis of patients in the second cohort to 2004 to guarantee a minimum follow-up period of 4 years until the study closing date on December 31, 2008.

Statistical methods

Actuarial survival curves were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier and compared by the log-rank test. Relative survival was calculated according to both the cohort method proposed by Dickman et al13 and the period analysis method described by Brenner et al.14 Relative survival is defined as the ratio between the actuarial survival observed in the group of patients studied and the expected survival derived from a subset of the general population matched to the patients by age, sex, and calendar year of diagnosis. Relative survival allows comparing patient's survival across distant time periods after discounting changes in the population life expectancy and other demographic effects. The period analysis method is more sensitive to the most recent improvements in survival (eg, as a consequence of a novel treatment) than is the Dickman method, whereas the latter better represents the survival of a well-defined cohort of patients. Estimates of expected survival were calculated by the Ederer II method13 from Spanish life tables stratified by age, sex, and calendar year that were obtained from the Human Mortality Database.15

Disease-specific incidence mortality represents the excess mortality observed in patients with CLL over the expected mortality derived from the general population. It can be regarded as the CLL-attributable mortality and is usually expressed in terms of incidence rate per person-years of follow-up. Because relative survival is calculated by the life-table method, in which censored patients are ascribed a mid-period follow-up, 15 patients followed for less than 1 month or patients censored alive before 3 months of follow-up were excluded from further analysis so not to artifactually inflate the short-term relative survival.

Both parametric (t test, comparison of 2 proportions) and nonparametric (χ2 test, Fisher exact test) tests were used to compare demographic and clinical characteristics.16 Disease-specific mortality rates and relative survival curves were compared by Poisson regression13 with correction for overdispersion when needed. All tests were 2-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered significant. All the analyses were conducted with the use of the Stata 10 software (www.stata.com). For relative survival analysis, the Stata routines developed by Paul Dickman (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; available at www.pauldickman.com) were used.

This study was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of the Hospital Clínic Barcelona. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Characteristics of the series at diagnosis

The principal characteristics of the whole series and of the 2 cohorts of patients according to the year of diagnosis are shown in Table 1. Median age at presentation was higher in patients diagnosed between 1980 and 1994 than in those seen from 1995 to 2004 (68 vs 64 years; P = .005). The distribution by age groups showed a shift toward younger age at diagnosis in the more recent cohort, with a significant increase in the proportion of patients younger than 70 y (55.9% vs 63%; P = .039). There was a preponderance of men in both groups (54.3% vs 58.4%; P = NS).

Clinical characteristics

| . | 1980-1994 . | 1995-2004 . | P . | Overall (1980-2008) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 451 | 365 | 929 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 68 (24-89) | 64 (28-96) | .005 | 67 (24-97) |

| Age younger than 70 y, % | 55.9 | 63.0 | .039 | 58.0 |

| Age distribution, % | < .001 | |||

| Younger than 50 y | 10.0 | 18.1 | 13.3 | |

| 50-59 y | 16.0 | 22.7 | 18.7 | |

| 60-69 y | 29.9 | 22.2 | 25.9 | |

| 70-79 y | 30.4 | 21.9 | 27.8 | |

| 80 y or older | 13.7 | 15.1 | 14.2 | |

| Sex, male, % | 54.3 | 58.4 | NS | 56.7 |

| Binet stage, % | .001 | |||

| A | 69.1 | 80.1 | 75.6 | |

| B | 18.6 | 13.0 | 15.6 | |

| C | 12.3 | 6.9 | 8.8 | |

| B symptoms, % | 4.3 | 6.9 | NS | 5.0 |

| Blood lymphocyte count, ×109/L, mean (SD) | 36.9 (57.7) | 26.3 (44.0) | .003 | 30.5 (49.7) |

| Fewer than 10 × 109/L, % | 20.6 | 35.1 | < .001 | 29.8 |

| 10-30 × 109/L, % | 52.4 | 43.7 | < .001 | 47.1 |

| More than 30 × 109/L, % | 27.0 | 21.3 | < .001 | 23.1 |

| Hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL, % | 6.3 | 4.7 | NS | 5.0 |

| Platelet count less than 100 × 109/L, % | 6.5 | 3.9 | NS | 4.9 |

| Increased LDH level, % (n = 694) | 17.4 | 11.3 | .022 | 14.0 |

| Increased β2m level, % (n = 498) | 45.0 | 34.0 | .039 | 39.0 |

| Doubling time fewer than 12 mo, % (n = 498) | 29.3 | 21.2 | .038 | 22.5 |

| Diffuse bone marrow biopsy, % (n = 603) | 12.9 | 7.9 | .05 | 7.3 |

| . | 1980-1994 . | 1995-2004 . | P . | Overall (1980-2008) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 451 | 365 | 929 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 68 (24-89) | 64 (28-96) | .005 | 67 (24-97) |

| Age younger than 70 y, % | 55.9 | 63.0 | .039 | 58.0 |

| Age distribution, % | < .001 | |||

| Younger than 50 y | 10.0 | 18.1 | 13.3 | |

| 50-59 y | 16.0 | 22.7 | 18.7 | |

| 60-69 y | 29.9 | 22.2 | 25.9 | |

| 70-79 y | 30.4 | 21.9 | 27.8 | |

| 80 y or older | 13.7 | 15.1 | 14.2 | |

| Sex, male, % | 54.3 | 58.4 | NS | 56.7 |

| Binet stage, % | .001 | |||

| A | 69.1 | 80.1 | 75.6 | |

| B | 18.6 | 13.0 | 15.6 | |

| C | 12.3 | 6.9 | 8.8 | |

| B symptoms, % | 4.3 | 6.9 | NS | 5.0 |

| Blood lymphocyte count, ×109/L, mean (SD) | 36.9 (57.7) | 26.3 (44.0) | .003 | 30.5 (49.7) |

| Fewer than 10 × 109/L, % | 20.6 | 35.1 | < .001 | 29.8 |

| 10-30 × 109/L, % | 52.4 | 43.7 | < .001 | 47.1 |

| More than 30 × 109/L, % | 27.0 | 21.3 | < .001 | 23.1 |

| Hemoglobin level less than 10 g/dL, % | 6.3 | 4.7 | NS | 5.0 |

| Platelet count less than 100 × 109/L, % | 6.5 | 3.9 | NS | 4.9 |

| Increased LDH level, % (n = 694) | 17.4 | 11.3 | .022 | 14.0 |

| Increased β2m level, % (n = 498) | 45.0 | 34.0 | .039 | 39.0 |

| Doubling time fewer than 12 mo, % (n = 498) | 29.3 | 21.2 | .038 | 22.5 |

| Diffuse bone marrow biopsy, % (n = 603) | 12.9 | 7.9 | .05 | 7.3 |

NS indicates not significant; and β2m, β2-microglobulin.

The proportion of patients in low-risk clinical stage (Binet A) at diagnosis was significantly higher from 1995 to 2004 than in the previous period (80.1% vs 69.1%; P = .001). Likewise, patients more recently diagnosed had a lower blood lymphocyte count at presentation (mean, 26.3 × 109/L vs 37 × 109/L; P = .003) and lower LDH (11.3% vs 17.4%; P = .022) and β2-microglobulin (34% vs 45%; P = .039) serum levels.

Treatment modalities

Not unexpectedly, most of the patients diagnosed between 1980 and 1994 who required treatment received alkylating agents (96.4%). Since 1995, the proportion of patients who were given purine analogs, alone or in combination with other agents, increased (Table 2). Moreover, the number of patients receiving hemopoietic stem cell transplantation was higher in the period 1995-2004 than in the 1980-1995 group (9.3% vs 2.9%; P < .001; Table 2). Both autologous (4.1% vs 1.8%; P = .045) and allogeneic (5.2% vs 1.1%; P = .001) transplantations were more frequently performed in the second cohort, with allogeneic reduced-intensity conditioning transplantation being only performed in that group. When treatment modality was broken down according to patients' age, differences in treatment were concentrated in patients younger than 70 years (supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Almost all patients younger than 70 years with advanced stage (Binet B/C) at diagnosis were treated (supplemental Table 2).

Treatment modalities

| . | 1980-1994 . | 1995-2004 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated, n (%) | 212 (48.3) | 189 (53.8) | NS |

| First-line treatment | < .001 | ||

| Alkylating agents, % | 96.4 | 48.3 | |

| PA, % | 3.6 | 22.8 | |

| PA + other cytotoxics, % | 18.9 | ||

| Rit + PA in combination, % | 10.0 | ||

| Hemopoietic stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 13 (2.9) | 34 (9.3) | < .001 |

| Autologous, n (%) | 8 (1.8) | 15 (4.1) | .045 |

| Allogeneic, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 19 (5.2) | .001 |

| Conventional allogeneic, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 13 (3.6) | .018 |

| RIC, n (%) | 0 | 6 (1.6) | .008 |

| Any time | < .001 | ||

| PA, %* | 16.0 | 11.0 | |

| PA + other cytotoxics, % | 11.0 | 42.0 | |

| Rit + PA in combination, % | 0.5 | 13.0 |

| . | 1980-1994 . | 1995-2004 . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treated, n (%) | 212 (48.3) | 189 (53.8) | NS |

| First-line treatment | < .001 | ||

| Alkylating agents, % | 96.4 | 48.3 | |

| PA, % | 3.6 | 22.8 | |

| PA + other cytotoxics, % | 18.9 | ||

| Rit + PA in combination, % | 10.0 | ||

| Hemopoietic stem cell transplantation, n (%) | 13 (2.9) | 34 (9.3) | < .001 |

| Autologous, n (%) | 8 (1.8) | 15 (4.1) | .045 |

| Allogeneic, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 19 (5.2) | .001 |

| Conventional allogeneic, n (%) | 5 (1.1) | 13 (3.6) | .018 |

| RIC, n (%) | 0 | 6 (1.6) | .008 |

| Any time | < .001 | ||

| PA, %* | 16.0 | 11.0 | |

| PA + other cytotoxics, % | 11.0 | 42.0 | |

| Rit + PA in combination, % | 0.5 | 13.0 |

PA indicates purine analogs; Rit, rituximab; and RIC, reduced-intensity allogeneic.

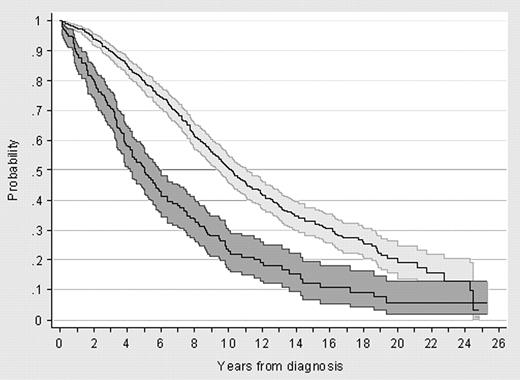

Survival

After a median follow-up of 5.9 years (range, 0.1-25.4 years), 500 (55%) of the 914 assessable patients have died. Of those censored alive, 349 were still alive and 65 (7.1% of the whole series) were lost to follow-up when the study was closed. Median survival for the whole series was 8.8 years from diagnosis (95% CI, 8.0-9.5 years from diagnosis), and 25% of patients were projected to survive 16 years or longer (Figure 1). Kaplan-Meier survival curves according to Binet stage at diagnosis are depicted in Figure 2, whereas survival of all patients with CLL in comparison to that of the general population is shown in Figure 3. When demographic effects of age, sex, and year of diagnosis were compensated, a marked effect of the disease on patients' life expectancy was observed. Indeed, survival of the patients at 5, 10, and 15 years from diagnosis was 80%, 56%, and 49%, respectively, of that expected in the general population. Survival of patients in Binet stage A began to diverge from that of the general population after 5 years from diagnosis and remained at 72% of the theoretical survival 10 years after diagnosis. In contrast, patients in Binet stage B/C had a significantly higher mortality starting from the first year of follow-up, and their 10-year survival was 29% of that expected in the general population.

Observed survival in patients with CLL compared with the estimated survival for a subset of the general population matched with the patients by age, sex, and calendar year at diagnosis. (A) Whole series; (B) Binet stage A; (C) Binet stage B/C.

Observed survival in patients with CLL compared with the estimated survival for a subset of the general population matched with the patients by age, sex, and calendar year at diagnosis. (A) Whole series; (B) Binet stage A; (C) Binet stage B/C.

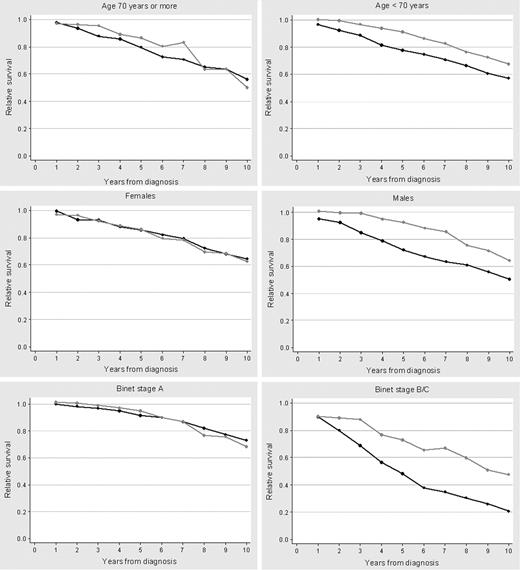

Relative survivals of patients diagnosed in 1980-1994 and 1995-2004 are shown in Figure 4. Both the cohort and the period analysis methods showed an improved relative survival for patients diagnosed in the more recent period. However, the continuous decline in relative survival curves indicates a persistent long-term mortality attributable to CLL. Relative survival curves calculated by the period analysis were similar to those estimated by the cohort method and did not improve when the analysis of patients more recently diagnosed was extended up to 2008 (data not shown). Compared with patients diagnosed between 1980 and 1994, the relative survival of patients seen from 1995 to 2004 improved for patients younger than 70 years (P = .032) and those in Binet stage B/C (P = .002). In contrast, no significant improvement was observed in patients aged 70 years or older or in patients in Binet stage A (Figure 5). Finally, there was a trend for a greater improvement of relative survival in men than in women (P = .057).

Ten-year relative survival curves for patients with CLL diagnosed in the calendar periods 1980-1994 or 1995-2004, calculated by the cohort method and the period analysis method. (A) Relative survival by cohort analysis; (B) relative survival by period analysis.

Ten-year relative survival curves for patients with CLL diagnosed in the calendar periods 1980-1994 or 1995-2004, calculated by the cohort method and the period analysis method. (A) Relative survival by cohort analysis; (B) relative survival by period analysis.

Ten-year relative survival curves by age group, sex, and Binet stage at diagnosis according to the calendar period (1980-1994 or 1995-2004) in which the patients with CLL were diagnosed. (A) Age older than 70 years; (B) age younger than 70 years; (C) females; (D) males; (E) Binet stage A; (F) Binet stage B/C.

Ten-year relative survival curves by age group, sex, and Binet stage at diagnosis according to the calendar period (1980-1994 or 1995-2004) in which the patients with CLL were diagnosed. (A) Age older than 70 years; (B) age younger than 70 years; (C) females; (D) males; (E) Binet stage A; (F) Binet stage B/C.

The 5-year and 10-year mortality attributable to CLL significantly decreased from the first to the second period, this reduction being more striking at 5 years after diagnosis (Table 3). The increased relative survival in the more recent period was driven by patients who were younger than 70 years with Binet stages B/C at diagnosis, this being the only subgroup of patients whose outcome improved over the time (Figure 6).

CLL-attributable mortality for patients diagnosed in the calendar periods 1980-1994 and 1995-2004

| . | Period 1980-1994 . | Period 1995-2004 . | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients . | Deaths per 1000 patient-years . | No. of patients . | Deaths per 1000 patient-years . | |||

| At 5 years from diagnosis | ||||||

| All patients | 448 | 52 | 358 | 24 | 0.46 (0.28-0.78) | .004 |

| Binet stage A and age younger than 70 y | 167 | 13 | 178 | 14 | 1.08 (0.35-3.31) | .882 |

| Binet stage A and age 70 y and older | 142 | 35 | 108 | 14 | 0.40 (0.06-2.82) | .357 |

| Binet stageB/C and age younger than 70 y | 83 | 143 | 48 | 29 | 0.40 (0.08-0.52) | .001 |

| Binet stage B/C and age 70 y and older | 52 | 135 | 21 | 210 | 1.55 (0.68-3.52) | .292 |

| At 10 years from diagnosis | ||||||

| All patients | 448 | 62 | 358 | 41 | 0.65 (0.48-0.89) | .007 |

| Binet stage A and age younger than 70 y | 167 | 29 | 178 | 27 | 0.92 (0.54-1.55) | .755 |

| Binet stage A and age 70 y and older | 142 | 52 | 108 | 45 | 0.86 (0.43-1.73) | .679 |

| Binet stage B/C and age younger than 70 y | 83 | 144 | 48 | 48 | 0.33 (0.18-0.60) | < .001 |

| Binet stage B/C and age 70 y and older | 52 | 164 | 21 | 197 | 1.20 (0.58-2.50) | .622 |

| . | Period 1980-1994 . | Period 1995-2004 . | Incidence rate ratio (95% CI) . | P . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients . | Deaths per 1000 patient-years . | No. of patients . | Deaths per 1000 patient-years . | |||

| At 5 years from diagnosis | ||||||

| All patients | 448 | 52 | 358 | 24 | 0.46 (0.28-0.78) | .004 |

| Binet stage A and age younger than 70 y | 167 | 13 | 178 | 14 | 1.08 (0.35-3.31) | .882 |

| Binet stage A and age 70 y and older | 142 | 35 | 108 | 14 | 0.40 (0.06-2.82) | .357 |

| Binet stageB/C and age younger than 70 y | 83 | 143 | 48 | 29 | 0.40 (0.08-0.52) | .001 |

| Binet stage B/C and age 70 y and older | 52 | 135 | 21 | 210 | 1.55 (0.68-3.52) | .292 |

| At 10 years from diagnosis | ||||||

| All patients | 448 | 62 | 358 | 41 | 0.65 (0.48-0.89) | .007 |

| Binet stage A and age younger than 70 y | 167 | 29 | 178 | 27 | 0.92 (0.54-1.55) | .755 |

| Binet stage A and age 70 y and older | 142 | 52 | 108 | 45 | 0.86 (0.43-1.73) | .679 |

| Binet stage B/C and age younger than 70 y | 83 | 144 | 48 | 48 | 0.33 (0.18-0.60) | < .001 |

| Binet stage B/C and age 70 y and older | 52 | 164 | 21 | 197 | 1.20 (0.58-2.50) | .622 |

Ten-year relative survival curves for patients younger than 70 years in Binet stage B/C according to whether they were diagnosed in the calendar periods 1980-1994 or 1995-2004.

Ten-year relative survival curves for patients younger than 70 years in Binet stage B/C according to whether they were diagnosed in the calendar periods 1980-1994 or 1995-2004.

Discussion

Modern therapy has dramatically improved response rate and progression-free survival in patients with CLL. However, CLL continues to be incurable, and the effect of newer therapies on overall survival is far from being clear. Although studies based on historical controls show that survival seems to be improving,4,5,7 these analyses cannot segregate the benefit provided by newer therapies (and better general medical care) from the natural increase in the life expectancy of the general population.4,5

The study of large series from single institutions may offer important information about prognosis and survival of patients with CLL over time. The Hospital Clínic of Barcelona is a general hospital, serving an area of 500 000 inhabitants, which provides both primary and specialized care and is also a referral center for CLL. Against this background, we analyzed a large series of patients prospectively registered in our database at diagnosis and closely followed (only 7% of patients were lost to follow-up) to ascertain changes in the presentation patterns and clinical outcome, irrespectively of clinical stage or treatment requirement.

The results of this study show that CLL shortens life expectancy not only in patients with advanced disease (Binet stage B/C) but in all patients with CLL, independently of their tumor burden at diagnosis (supplemental Table 3). For patients with low-risk disease (Binet stage A) survival begins to diverge from that of the general population after 5 years from diagnosis, probably reflecting disease progression.

Despite the overall poor prognosis, we also found that the relative survival of patients with CLL is improving, particularly in younger (< 70 years) patients, in agreement with population-based studies.10 To further characterize those patients in whom survival has improved, we analyzed the relative survival according to the clinical stage at diagnosis and found that the increased survival in the 1995-2004 cohort was concentrated in patients younger than 70 years with advanced disease. In contrast, the relative survival of patients with low-risk disease (Binet stage A) has remained basically unchanged over the years, this being true for both the Dickman method and the Brenner period analysis, which is more sensitive to recent improvements in survival. However, because CLL progression rate from low- to high-risk is 2% to 5% per year, the 1995-2004 cohort should be followed for a longer period of time to draw firmer conclusions.17

When analyzing survival according to sex, there was a trend for a greater improvement of relative survival in men than in women, confirming previous observations by Brenner et al.10 Male sex has been associated with a more advanced disease at presentation18 and poorer biologic features (eg, unmutated IgVH genes and high expression of CD38).19,20 It could be argued that male patients might benefit more than female patients from newer therapies, but this notion has not been confirmed.8,21

Although this study was not designed to respond to that question, it is tempting to link the improvement in survival to a better management, including more effective antileukemia therapies. In fact, the 2 cohorts studied roughly correspond to 2 different periods in the history of CLL treatment: alkylators (1980-1994) and purine-analog–based therapies (1995 and onward). Of note, the group of patients whose survival has been most improved, namely those younger than 70 years and with advanced stage, is that group mainly treated with modern therapy. Unfortunately, however, this group of patients is not representative of the whole population of patients with CLL, and, indeed, it only represents 20% of all our patients. Patients older than 70 years were similarly treated over the time, a large proportion of them receiving alkylating agents. In line with this, it is important to emphasize that in recent clinical trials older patients are clearly underrepresented,3-5,8,22-24 which is unfortunate because, although more aggressive treatments are usually poorly tolerated by the elderly, treatment recommendations should be based on patients' general status and comorbidity rather than on age only.25

Besides newer treatments, additional factors such as better supportive care and the earlier detection of the disease might be contributing to the observed longer survival in more recent years. In this regard, the present study confirms that CLL is increasingly being diagnosed in patients with low-risk disease26-28 and low tumor burden (eg, lower blood lymphocyte counts, LDH, and β2-microglobulin serum levels). This fact is most probably due to the increasing use of routine blood tests and the availability of flow cytometry as a diagnostic tool.29 Note that, in contrast with standard methods, the relative survival analysis tempers the lead-time bias that an earlier or accidental diagnosis may produce when estimating survival.30 Our results indicate that the earlier detection of the disease does not translate by itself into a longer survival. Indeed, relative survival for patients with low-risk clinical stage at diagnosis (Binet stage A) has not significantly changed from 1980 to 2004. These findings highlight the importance of identifying better prognostic factors in patients with low disease burden at diagnosis, as well as that of clinical trials aimed at challenging the notion that these patients should not be treated unless they progress.31,32

In conclusion, this study shows, in a single center series, that CLL shortens life expectancy across all age groups and clinical stages, but also that survival is steadily improving, particularly in younger patients with advanced disease, most likely because of modern therapy. There is, however, an important need for improving the outcome of all patients with CLL. Lessons from recent clinical trials (eg, key role of chemoimmunotherapy, importance of achieving the best possible response, relevance of biomarkers such as 11q− and 17p− to select therapy, importance of microenvironmental cells in sustaining the neoplastic population, defects of T cells) should all be taken into account when planning future treatment protocols. Only in this way can the prognosis of patients with CLL continue to improve, and the ultimate goal of therapy, curing the disease, will someday become a reality.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Artur Conesa from the Clinical Documentation Area, Informatics Unit, Hospital Clínic Barcelona, and Índice Nacional de Defunciones, Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo.

This work was supported by grants FISS 080304 and 080211, 051810 from Marató de TV3, International Foundation José Carreras 08/P-CR and 08/P-EM, CLL Global Foundation, and Farreras-Valentí Foundation.

Authorship

Contribution: P.A. reviewed the data, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript; A.P. performed the statistical analysis and reviewed the manuscript; C.R. discussed the study design and performed the statistical analysis; M.A. and M.R. reviewed consistency of diagnosis in the database; E.G., C.M., A.M., and K.H. retrieved clinical information; N.V. reviewed the manuscript; E.C. coordinated diagnostic revision; F.B. obtained clinical information and reviewed the manuscript; and E.M. designed the study, wrote the manuscript along with P.A., and approved its final version.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Emili Montserrat, Institute of Hematology and Oncology, Department of Hematology, Hospital Clínic, Villarroel, 170, 08036 Barcelona, Spain; e-mail: emontse@clinic.ub.es.