Abstract

Tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) is approved for treatment of ischemic stroke patients, but it increases the risk of intracranial bleeding (ICB). Previously, we have shown in a mouse stroke model that stromelysin-1 (matrix metalloproteinase-3 [MMP-3]) induced in endothelial cells was critical for ICB induced by t-PA. In the present study, using bEnd.3 cells, a mouse brain–derived endothelial cell line, we showed that MMP-3 was induced by both ischemic stress and t-PA treatment. This induction by t-PA was prevented by inhibition either of low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein (LRP) or of nuclear factor-κB activation. LRP was up-regulated by ischemic stress, both in bEnd.3 cells in vitro and in endothelial cells at the ischemic damage area in the mouse stroke model. Furthermore, inhibition of LRP suppressed both MMP-3 induction in endothelial cells and the increase in ICB by t-PA treatment after stroke. These findings indicate that t-PA deteriorates ICB via MMP-3 induction in endothelial cells, which is regulated through the LRP/nuclear factor-κB pathway.

Introduction

Tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA) is a thrombolytic agent that degrades fibrin clots through activation of plasminogen to plasmin.1 Although t-PA given within 3 hours from onset of ischemic stroke improves the clinical outcome in patients, it induces a 10-fold increase of symptomatic intracranial bleeding (ICB).2 Furthermore, delayed t-PA treatment beyond 3 hours is associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic transformation and with enhanced brain injury.3 The increase of ICB by delayed treatment with t-PA was also observed in a mouse stroke model.4

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a family of zinc endopeptidases, contribute to tissue remodeling through degradation of extracellular matrix proteins. For ICB associated with ischemic stroke, MMPs have a key role in the degradation of the barrier of blood vessels.5,6 Previously, we have shown that the increase in ICB caused by t-PA treatment was impaired in mice with gene deficiency of MMP-3 (stromelysin-1) and that a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor suppressed ICB in wild-type but not in MMP-3–deficient mice.7 MMP-3 can be activated by plasmin8 and has a broad-spectrum substrate specificity.9 Furthermore, t-PA treatment induced MMP-3 selectively in endothelial cells at the ischemic damaged area in a mouse stroke model,7 suggesting that MMP-3 may be involved in degradation of the barrier of blood vessels and contribute to ICB. However, the mechanism underlying MMP-3 induction by t-PA remained unknown and is the subject of the present study.

Low-density lipoprotein receptor–related protein (LRP), a member of the lipoprotein receptor family, is a scavenger receptor that binds a variety of biologic ligands and is thought to be primarily involved in lipoprotein metabolism10 and in clearance of protease-inhibitor complexes in the adult brain.11 Recent reports have shown that t-PA induces MMP-9 in brain endothelial cells12 and increases the blood-brain barrier permeability via LPR activation,13 suggesting a role for LRP as a t-PA receptor. It has also been reported that LRP activation by t-PA stimulates the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway.14

In this study, we have evaluated whether the LRP/NF-κB pathway plays a role in MMP-3 induction by t-PA treatment. Therefore, we used bEnd.3 cells, a transformed endothelial cell line derived from mouse brain, as well as a mouse stroke model.

Methods

Reagents

Recombinant human t-PA (Alteplase; Activase) was purchased from Genentech Inc. It was inactivated by incubation with D-Phe-Pro-Arg-chloromethylketone (Calbiochem); inactivation was confirmed using S-2258 (Chromogenix). Receptor-associated protein (RAP), which antagonizes binding of ligands to members of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, was purchased from Chemicon. The following antibodies were purchased: murine MMP-3 (R&D Systems), NF-κB (Calbiochem), histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1; Sigma-Aldrich), LRP (Progen and Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology). MG-132 (carbobenzoxy-L-leucyl-L-leucyl-L-norvalinal, a proteome inhibitor) was purchased from Chemicon. The probes for real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of LRP mRNA (Lrp1; 5′-TCGGCAGACCATCATCCAAG-3′, forward primer: MA072132-F and 5′-ATTGTCCGAGTTGGTGGCGTA-3′, reverse primer: MA072132-R) were purchased from Takara bio Inc. The primers for mouse β-actin (Takara bio Inc) were 5′-CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCCAAC-3′ (forward primer) and 5′-ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA-3′ (reverse primer).

Cell culture

bEnd.3 cells (a transformed mouse brain endothelial cell line) were used for in vitro studies. After culturing in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing fetal calf serum to confluence, oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD), which mimics ischemic stress, was applied using a combination of the Areopack KENKI system (Mitsubishi Gas) and cultured in DMEM without glucose (Invitrogen). After 6 hours of OGD, cells were further cultured in DMEM with 25 mM glucose under normoxia over 18 hours. Control cells were cultured in DMEM with 25 mM glucose for 24 hours under normoxia. t-PA (5-30 μg/mL), inactivated t-PA (20 μg/mL), or solvent was added at the end of 6 hours of OGD or of normoxia. To study the role of LRP in the induction of MMP-3, cells were treated with 200 nM of RAP or 2 μg/mL of anti-LRP antibody, 10 minutes before t-PA administration. To study the involvement of NF-κB, cells were treated with 10 μM MG-132 at the initiation of OGD.

Assays

MMP-3 levels were monitored by Western blotting. After the incubations, bathing media and cell extract were prepared15 and frozen at −20°C until used. MMP-3 was immunoprecipitated using polyclonal rabbit anti–mouse MMP-3 antiserum and eluted with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer.16 After SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and transfer to nitrocellulose paper, it was treated with a rat anti–mouse MMP-3 antibody followed by peroxidase conjugated rabbit anti–rat IgG. Signals were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare) and quantified by densitometry (LAS-3000 mini and Multi Gauge Version 3.0; Fuji film).

Translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus was measured by a combination of cell fractionation and Western blotting. First, the cytosolic fraction was removed by treatment with hypotonic buffer (10 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid-KOH, pH 7.8, containing 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 0.1% NP-40) containing proteinase inhibitors (1 mM dithiothreitol, 2 μg/mL aprotinin, 0.5 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride). Then the nuclear fraction was isolated by treatment with another hypertonic buffer (50 mM N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid-KOH, pH 7.8, containing 420 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2% glycerol) containing proteinase inhibitors. This fraction was subjected to SDS-PAGE, and after transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane treated with anti–NF-κB antibody followed by goat anti–rabbit IgG conjugated with peroxidase. Signals were quantified using the enhanced chemiluminescence system. To confirm the application of equivalent amount of sample in the experiments, subsequent Western blotting with anti-HDAC1, an internal control of nuclear protein, was performed with the nitrocellulose membrane.

LRP protein or mRNA was measured by Western blotting or real-time PCR, respectively. For Western blotting, immunoprecipitated cell extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE,15 and after transfer to nitrocellulose paper treated with anti-LRP antibody, followed by peroxidase conjugated goat anti–rabbit IgG. For the in vivo study, subsequent Western blotting with anti–β-actin, an internal control, was performed with the nitrocellulose membrane. For real-time PCR, 75 ng of total RNA prepared from cells using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was subjected to reverse transcription (SuperScript II; Invitrogen) to generate cDNA. Real-time PCR was preformed with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real time System single instrument (Takara bio Inc) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II reagent (Takara bio Inc). The thermal cycle conditions were as follows: hold for 30 seconds at 95°C, followed by 2-step polymerase chain reaction for 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 seconds, followed by 60°C for 30 seconds. β-Actin was used to normalize gene expression in all samples. Fold induction values were calculated by subtracting the mean difference of gene and β-actin cycle threshold Ct numbers for each treatment group from the mean difference of gene and β-actin Ct numbers for the control group and raising the difference to the power of 2 (2−ΔΔCt). The specific amplification of PCR was proven by the presence of only one peak in the dissociation curve and of a single band on 3% agarose gel electrophoresis.

To assess cell viability, bath media and cell lysate (using 2% Triton X-100) were collected and lactate dehydrogenase activity was measured (Roche Diagnostic). Viability was expressed as the percentage of activity in cell lysate versus total activity in bath media and cell lysate.

Thrombotic ischemic stroke and ICB

To evaluate ICB, we used a model of ischemic stroke induced photochemically by middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion, as described elsewhere.4,7,17 Male C57Bl/6 mice weighing 20 to 30 g were used. At 4 hours after MCA occlusion, 10 mg/kg of recombinant t-PA or the same volume of solvent was administered as a bolus in the tail or penile vein. To study the role of LRP in ICB, 1 or 2 mg/kg of RAP was administered as an intravenous bolus 5 minutes before t-PA administration. Animals were killed 20 hours after t-PA administration by overdose of Nembutal (Abbott) and perfused with saline. Brains were removed and placed in a matrix for sectioning into 1-mm-thick sections. The extent of ICB was determined as area (square millimeters) of hemorrhage in the caudal side of all brain sections, using planimetry.7 A good correlation between ICB determined with a biochemical method and by planimetry was shown previously.18

All animal experiments were approved by the ethical committee of the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine and the University of Leuven, and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health.19

Histologic analysis

At the end of the experiments, mice were perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde containing 75 mM lysine-HCl and 100 mM sodium meta-peroxide, and 7- to 10-μm cryosections of the brain were prepared. For analysis of MMP-3 or LRP expression, sections were stained with rat anti–mouse MMP-3 or anti–human LRP antibody in combination with goat anti–CD31 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as an endothelial marker, followed byfluorescein-conjugated anti–rat IgG or rodamine-conjugated anti–mouse or anti–goat IgG. Sections were mounted using VECTASHELD (Vector Laboratories) and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (Olympus DP-70 and DP manager; Olympus). Photographs taken with a 20× objective lens at room temperature were merged by WinROOF 5.0 (Mitani Corporation).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by analysis of variance followed by Fisher Protected Least Significant Difference test. P values less than .05 were considered significant.

Results

Effect of OGD and t-PA on MMP-3 synthesis in bEnd.3 cells

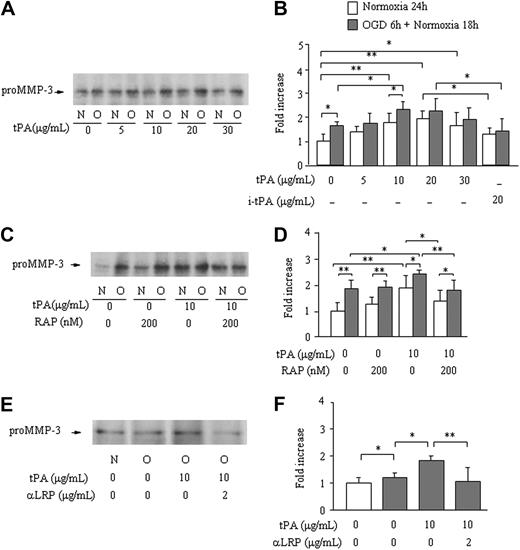

The (Pro)MMP-3 level in bathing media was significantly enhanced after 6 hours of OGD insult followed by 18 hours of normoxia (1.7 ± 0.14-fold increase), compared with 24 hours of normoxia (1.0 ± 0.20-fold). After 3 hours of OGD followed by 21 hours of normoxia, no effect was observed (0.89 ± 0.22-fold). Active MMP-3 was not detected in either of these experiments. Treatment with t-PA caused a significant dose-dependent increase in pro–MMP-3 levels, both after 24 hours of normoxia and after OGD and normoxia, with the maximum effect at a dose between 10 and 20 μg/mL (Figure 1A-B). This effect was not observed by treatment with inactivated t-PA (20 μg/mL; P = .07 under normoxia and P = .99 under OGD vs absence of t-PA; Figure 1B). Pretreatment with RAP (200 nM) prevented the increase in pro-MMP-3 secretion by active t-PA (10 μg/mL) under both normoxia and OGD conditions; in the absence of t-PA, however, RAP had no effect (Figure 1C-D). Treatment with an anti-LRP antibody (2 μg/mL) also prevented the increase in MMP-3 by active t-PA (Figure 1E-F). Both pro- and active MMP-3 in cell extracts were below detection in all experiments (data not shown).

Effect of OGD and of t-PA treatment on MMP-3 secretion by bEnd.3 cells. MMP-3 secretion from bEnd.3 cells after 6 hours of OGD followed by 18 hours of normoxia (O) in the absence or the presence of different concentrations of t-PA is monitored by Western blotting. Data are compared with bEnd.3 cells kept on normoxia (N) for 24 hours. Representative immunoblots (A,C,E) and quantitative data are as fold increase (B,D,F) of the effects of different concentrations of t-PA (A-B), active site-blocked t-PA (B), pretreatment with RAP (C-D), or an anti-LRP antibody (E-F) are also shown. Data represent mean ± SD of 4 to 9 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of OGD and of t-PA treatment on MMP-3 secretion by bEnd.3 cells. MMP-3 secretion from bEnd.3 cells after 6 hours of OGD followed by 18 hours of normoxia (O) in the absence or the presence of different concentrations of t-PA is monitored by Western blotting. Data are compared with bEnd.3 cells kept on normoxia (N) for 24 hours. Representative immunoblots (A,C,E) and quantitative data are as fold increase (B,D,F) of the effects of different concentrations of t-PA (A-B), active site-blocked t-PA (B), pretreatment with RAP (C-D), or an anti-LRP antibody (E-F) are also shown. Data represent mean ± SD of 4 to 9 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

NF-κB activation

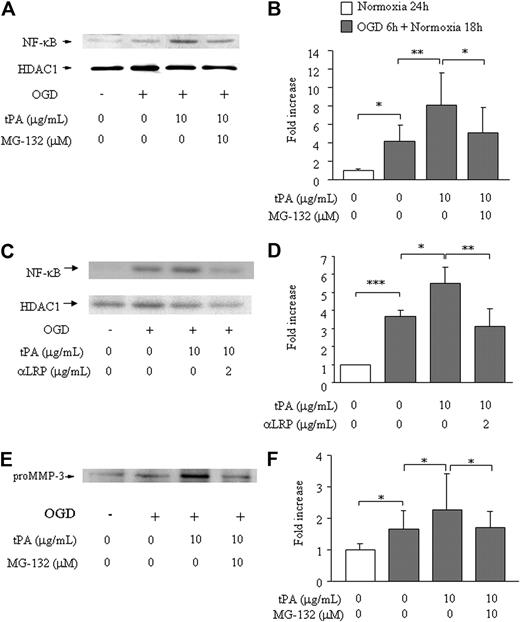

To evaluate the involvement of NF-κB, we studied the effect of MG-132 (a proteome inhibitor that inhibits degradation of I-κB and suppresses NF-κB translocation to the nucleus) and anti-LRP antibody on the MMP-3 induction. In bEnd.3 cells, OGD enhanced nuclear NF-κB levels (4.1- ± 1.7-fold) compared with only normoxia (1.0- ± 0.17-fold, Figure 2A-B). Addition of t-PA resulted in a further increase in nuclear NF-κB levels (to 8.1- ± 3.4-fold), which was reversed to the level with OGD alone by pretreatment with MG-132 (5.1- ± 2.8-fold). Similar reduction of NF-κB translocation was observed by treatment of anti-LRP antibody (1.0- ± 0.0-fold in normoxia, 3.7 ± 0.3 in OGD alone, 5.5 ± 0.9 in OGD/t-PA, 3.1 ± 1.0 in OGD/anti-LRP/t-PA, Figure 2C-D). The level of HDAC1 was comparable in all samples (Figure 2A,C). MMP-3 secretion paralleled NF-κB translocation (1.0- ± 0.20-fold in normoxia, 1.7- ± 0.57-fold with OGD alone, 2.3- ± 1.2-fold with OGD plus t-PA and, 1.7- ± 0.52-fold with the combination OGD/MG-132/t-PA; Figure 2E-F). These findings indicate that induction of MMP-3 by t-PA occurs through LRP and subsequent NF-κB activation.

Effects of MG-132 on NF-κB activation and MMP-3 secretion in bEnd.3 cells. NF-κB activation (A-D) or MMP-3 secretion (E-F) is shown on 6 hours of OGD followed by 18 hours of normoxia and t-PA treatment without or with addition of MG-132 (A,B,E,F) or anti-LRP antibody (C-D). Representative immunoblots against NF-κB and HDAC1 as an internal control (A,C) or pro–MMP-3 (E) are also shown. Quantitative data of NF-κB (B,D) and MMP-3 (F) are shown as fold increase and represent mean ± SD of 3 to 15 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Effects of MG-132 on NF-κB activation and MMP-3 secretion in bEnd.3 cells. NF-κB activation (A-D) or MMP-3 secretion (E-F) is shown on 6 hours of OGD followed by 18 hours of normoxia and t-PA treatment without or with addition of MG-132 (A,B,E,F) or anti-LRP antibody (C-D). Representative immunoblots against NF-κB and HDAC1 as an internal control (A,C) or pro–MMP-3 (E) are also shown. Quantitative data of NF-κB (B,D) and MMP-3 (F) are shown as fold increase and represent mean ± SD of 3 to 15 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Effect of OGD on LRP expression in bEnd.3 cells

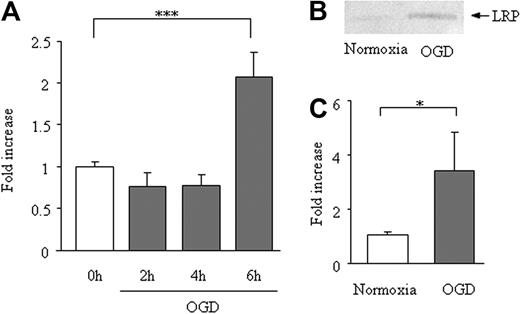

In bEnd.3 cells, 6 hours of OGD enhanced LRP mRNA expression (2.1- ± 0.28-fold vs 1.0- ± 0.05-fold; Figure 3A), the average Δ-Ct for β-actin and LRP was 19 and 28 cycles, respectively. The increase of LRP expression after 6 hours of OGD was confirmed at the protein level (Figure 3B-C). This increase could not be explained by an increase in cell count, because OGD for 6 hours reduced the bEnd.3 cell survival (to 75% ± 3.7% of normoxia).

Effect of OGD on LRP expression in bEnd.3 cells. Expression LRP mRNA (A) and protein (B-C) on 6 hours of OGD of bEnd.3 cells. Data are shown as fold increase and represent mean ± SD of 5 (A) or 6 (B-C) experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of OGD on LRP expression in bEnd.3 cells. Expression LRP mRNA (A) and protein (B-C) on 6 hours of OGD of bEnd.3 cells. Data are shown as fold increase and represent mean ± SD of 5 (A) or 6 (B-C) experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Role of LRP in MMP-3 induction and in enhanced ICB caused by t-PA

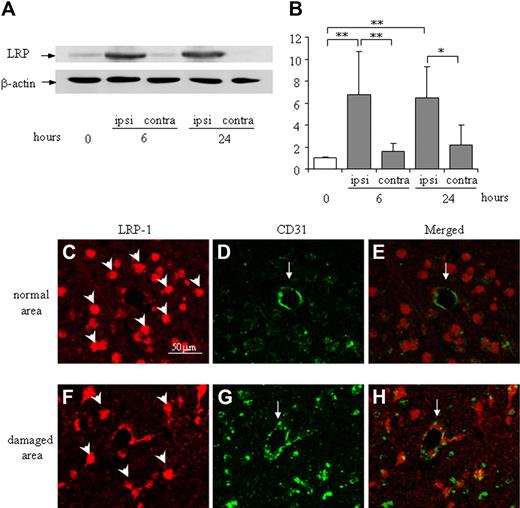

LRP expression in the ipsilateral hemisphere was significantly up-regulated by MCA occlusion at both 6 and 24 hours in the mouse stroke model, whereas LRP expression in the contralateral hemisphere was comparable with the naive condition (Figure 4A-B). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that LRP was mainly localized at globular CD31-positive endothelial cells (Figure 4F-H). In contrast, it was localized predominantly to neuron-like cells and not to endothelial cells in a normal brain area (Figure 4C-E).

Expression and localization of LRP in the damaged cortex of the mouse brain after MCA occlusion. (A) Representative immunoblots against LRP and β-actin as an internal control are shown. The expression of LRP is up-regulated in the ipsilateral hemisphere at 6 and 24 hours after MCA occlusion, whereas it is not changed in the contralateral hemisphere. (B) Quantitative data are shown as fold increase. Data are mean ± SD of 6 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01. ipsi indicates ipsilateral hemisphere; contra, contralateral hemisphere. The time after MCA-O is indicated in hours. Localization of LRP in the normal area (C-E) or the damaged border area (F-H) at 24 hours after MCA-O is shown by immunofluorescence microscopy. In the normal area, LRP immunoreactivity (red: rodamine) localized at neuron-like cells (arrowheads in panel C) but not at CD31 (green: fluorescein) positive endothelial cells (arrows in panels D-E). At the damaged border area, it localized at both globular cells (arrowhead in panel F) and CD31-positive endothelial cells (arrow in panels G-H). The scale bar represents 50 μm.

Expression and localization of LRP in the damaged cortex of the mouse brain after MCA occlusion. (A) Representative immunoblots against LRP and β-actin as an internal control are shown. The expression of LRP is up-regulated in the ipsilateral hemisphere at 6 and 24 hours after MCA occlusion, whereas it is not changed in the contralateral hemisphere. (B) Quantitative data are shown as fold increase. Data are mean ± SD of 6 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01. ipsi indicates ipsilateral hemisphere; contra, contralateral hemisphere. The time after MCA-O is indicated in hours. Localization of LRP in the normal area (C-E) or the damaged border area (F-H) at 24 hours after MCA-O is shown by immunofluorescence microscopy. In the normal area, LRP immunoreactivity (red: rodamine) localized at neuron-like cells (arrowheads in panel C) but not at CD31 (green: fluorescein) positive endothelial cells (arrows in panels D-E). At the damaged border area, it localized at both globular cells (arrowhead in panel F) and CD31-positive endothelial cells (arrow in panels G-H). The scale bar represents 50 μm.

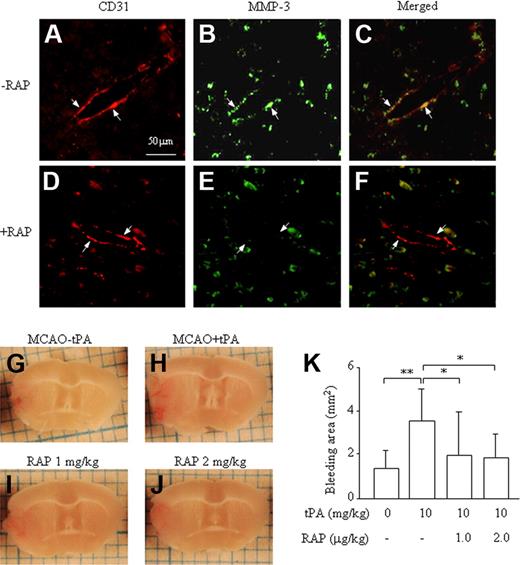

To explore a functional role of LRP in the induction of MMP-3 at endothelial cells in the damaged brain and in the increase in ICB induced by t-PA treatment, the effect of RAP was studied in the mouse stroke model. As shown in a previous report,7 MMP-3 immunoreactivity colocalized with the endothelial cell marker CD31 at the border of ischemic damage area in mice treated with t-PA (Figure 5A-C). The immunoreactivity was suppressed by pretreatment with 2 mg/kg of RAP (Figure 5D-F), which is in agreement with our in vitro data. Expression of MMP-3 was also observed in neurons in the normal area but was not affected by treatment with RAP (data not shown). Furthermore, pretreatment with 1 or 2 mg/kg of RAP suppressed the enhancement of ICB induced by t-PA (Figure 5G-K), indicating an association between increased ICB and MMP-3 induction by t-PA in endothelial cells, mediated via LRP.

Effect of RAP on up-regulation of MMP-3 expression and increased ICB induced by t-PA treatment after MCA occlusion in mice. Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP-3 and CD31 expression (A-F). MMP-3 immunoreactivity (green: fluorescein) colocalizing with CD31 immunoreactivity (red: rodamine) at the border zone of the damaged brain after t-PA treatment without (A-C) or with (D-F) RAP pretreatment. The arrows represent endothelial cells, and the scale bar represents 50 μm. Representative pictures are shown of a damaged brain section after MCA-O without t-PA treatment (G), with t-PA treatment (H), with t-PA and 1 mg/kg RAP (I), or with t-PA and 2 mg/kg RAP (J). (K) Quantitative data are also shown. Data represent mean ± SD of 8 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Effect of RAP on up-regulation of MMP-3 expression and increased ICB induced by t-PA treatment after MCA occlusion in mice. Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP-3 and CD31 expression (A-F). MMP-3 immunoreactivity (green: fluorescein) colocalizing with CD31 immunoreactivity (red: rodamine) at the border zone of the damaged brain after t-PA treatment without (A-C) or with (D-F) RAP pretreatment. The arrows represent endothelial cells, and the scale bar represents 50 μm. Representative pictures are shown of a damaged brain section after MCA-O without t-PA treatment (G), with t-PA treatment (H), with t-PA and 1 mg/kg RAP (I), or with t-PA and 2 mg/kg RAP (J). (K) Quantitative data are also shown. Data represent mean ± SD of 8 experiments. *P < .05; **P < .01.

Discussion

MMP-3 secretion by bEnd.3 cells, an endothelial cell line derived from mouse brain, is induced by both OGD and t-PA treatment. The induction by t-PA is suppressed either by inhibition of LRP with RAP or with an anti-LRP antibody, or by inhibition of the NF-κB pathway with MG-132. MMP-3 was not induced by inactivated t-PA, confirming the importance of the proteolytic activity. We also observed up-regulation of LRP expression under ischemic conditions in endothelial cells, both in vitro and in vivo; this apparently resulted in the selective induction by t-PA of MMP-3 in endothelial cell at ischemic damaged area in vivo. Furthermore, both MMP-3 expression in endothelial cells and increased ICB induced by t-PA in vivo were suppressed by pretreatment with RAP, supporting a critical role of the t-PA/LRP/NF-κB/MMP-3 pathway in ICB.

t-PA induces MMP-3 through the LRP/NF-κB pathway

t-PA is a serine proteinase that induces thrombolysis through plasmin generation from plasminogen. However, recent studies have indicated that t-PA also acts through plasmin(ogen)-independent mechanisms, including LRP activation under various physiologic and pathophysiologic conditions.20-22 LRP is known to participate not only in endocytosis of extracellular proteins, but also in intracellular signal transduction.23 Furthermore, coupling of the LRP and NF-κB pathways has been observed in macrophages and endothelial cells.24,25 Thus, the involvement of the LRP/NF-κB pathway was reported in the induction of MMP-9 by t-PA in an endothelial cell line.12 In the present study, we showed that the induction of NF-κB and MMP-3 by t-PA under ischemic stress was suppressed by MG-132 and that NF-κB induction was suppressed by anti-LRP antibody, demonstrating that induction of MMP-3 by t-PA also occurs via the LRP/NF-κB pathway. It cannot be excluded that activation of this pathway also induces other genes. The increase in MMP-3 by t-PA seen under ischemic stress was relatively modest in bEnd.3 cells (1.5- to 2.5-fold over normoxic control), which may be the result of a relatively high level of MMP-3 secretion under normoxic conditions in cell culture; in contrast, MMP-3 expression is very low in endothelial cells of the naive brain and is immunohistochemically undetectable.7

Role of MMP-3 in endothelial cells

MMP-3 is induced by t-PA not only in bEnd.3 cells in vitro under ischemic stress but also in endothelial cells at the ischemic border zone in vivo. It is conceivable that the increase in ICB by t-PA treatment occurs via MMP-3 induction. Because MMP-3 has a broad substrate specificity for extracellular proteins,9 it plays a key role in tissue remodeling. Furthermore, previous reports showed that MMP-3 was induced in endothelial cells by stimulation of cytokines26 or by overexpression of EST-1,27 a transcriptional factor associated with endothelial cell proliferation, suggesting an involvement of MMP-3 in vessel remodeling associated with endothelial cell proliferation. Therefore, t-PA may contribute to the vascular remodeling process, as supported by the observation that it increases blood-brain barrier permeability,13 which could be associated with angiogenesis.28

In addition, MMP-3 induction associated with NF-κB activation has been widely observed in pathologic processes, such as glioma,29 atherosclerosis,30 and rheumatoid arthritis,31 although no canonical NF-κB sites were identified in the promoter sequence of MMP-3.32 Because these pathologic processes are associated with tissue remodeling, it is possible that MMP-3 induction by t-PA results in the acceleration of cellular response on remodeling.

LRP up-regulation in endothelial cells under ischemic conditions

As shown in this study both in vitro and in vivo, LRP expression in endothelial cells is up-regulated by ischemic stress. Because LRP functions as a receptor for t-PA, the sensitivity of endothelial cells to t-PA will be increased under ischemic conditions. This may explain the observation that increased ICB7,12 or blood-brain barrier permeability13 is induced selectively at ischemic damage sites, even if t-PA is administered systemically. Furthermore, we also observed that LRP was increased only after 6 hours of OGD in bEnd.3 cells, suggesting that its induction was relatively delayed after exposure of endothelial cells to ischemic stress. This is consistent with the clinical or experimental findings that ICB after stroke is not increased by early but only by delayed treatment with t-PA.2,4 Up-regulation of LRP was also observed in neurons under ischemic conditions.14 Therefore, the increase in LRP at the ischemic hemisphere may result in increased LPR expression not only by endothelial cells but also by neurons surrounding the damage area.

LRP also participates in the scavenging of t-PA, the complex of t-PA with plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and of MMP-9.33 Thus, the up-regulation of LRP may also affect matrix remodeling through regulation of the balance of these molecules in the intercellular space.

Proteolytic activity of t-PA and MMP-3 induction

Both the increase in ICB and the induction of MMP-3 via LRP by t-PA required its proteolytic activity, suggesting that receptor binding is not sufficient to trigger these effects. This in consistent with our previous report that plasminogen is essential for t-PA–mediated ICB increase, indicating that plasmin generation is required. However, it has been shown that plasminogen is not necessary for LRP activation,13 suggesting a direct proteolytic effect of t-PA on LRP activation. The functional link with MMP-3 induction remains, however, enigmatic. Possibly, protease-activated receptors (PARs), which are activated by proteolytic cleavage of their extracellular amino-terminal domain, are involved.34 Direct activation of PARs by t-PA has, however, not been shown. Because LRP and PARs are colocalized at lipid rafts,35,36 concentrations of t-PA by LRP at rafts may lead to activation of PARs and in turn to NF-κB activation.37 Thus, PARs represent intriguing potential targets for t-PA, although other substrates cannot be excluded at present.

Therapeutic perspectives

The increase in both ICB and MMP-3 induction by t-PA was suppressed by treatment with RAP, suggesting that ICB caused by t-PA could be suppressed by LRP inhibition. MMP-9 in human endothelial cells is also induced by t-PA through LRP.12 However, our previous studies indicated that MMP-9 may be involved in ICB induced by the ischemic stroke itself, rather than in the increased ICB caused by t-PA treatment. This is suggested by previous findings that MMP-9 expression was already increased at endothelial cells in the ischemic brain after stroke,7,12 whereas t-PA treatment did not alter either the amount or the distribution of MMP-9 in the brain.6,7 Clinically, suppression of both ICB induced by t-PA and that associated with ischemic stress itself would be beneficial. Interestingly, BB-94, a broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor, suppressed the enhancement of ICB induced by t-PA treatment of rats with embolic focal ischemia.6 It remains to be shown whether LRP antagonists, through impairment of both MMP-3 and MMP-9 induction, may have the potential to suppress ICB in patients with stroke.

An Inside Blood analysis of this article appears at the front of this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank B. Van Hoef (KU Leuven) for excellent technical assistance.

This study was supported by the Mitsubishi Pharma Research Foundation and the Ministry of Education Culture of Japan (grant 20790204 to Y.S.) and by Excellentie Financiering KU Leuven (EF/05/013 to N.N., H.R.L.).

Authorship

Contribution: Y.S. and N.N. designed and performed research; K.Y. and J.K. performed LRP studies; H.R.L. supervised and performed MMP-3 studies; and K.U. supervised the study.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Nobuo Nagai, Department of Physiology, Kinki University School of Medicine, Ohnohigashi 377-2, Osakasayama, Osaka 589-8511, Japan; e-mail: nagainnn@med.kindai.ac.jp.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal