Abstract

Tissue infiltration of phagocytes exacerbates several human pathologies including chronic inflammations or cancers. However, the mechanisms involved in macrophage migration through interstitial tissues are poorly understood. We investigated the role of Hck, a Src-family kinase involved in the organization of matrix adhesion and degradation structures called podosomes. In Hck−/− mice submitted to peritonitis, we found that macrophages accumulated in interstitial tissues and barely reached the peritoneal cavity. In vitro, 3-dimensional (3D) migration and matrix degradation abilities, 2 protease-dependent properties of bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs), were affected in Hck−/− BMDMs. These macrophages formed few and undersized podosome rosettes and, consequently, had reduced matrix proteolysis operating underneath despite normal expression and activity of matrix metalloproteases. Finally, in fibroblasts unable to infiltrate matrix, ectopic expression of Hck provided the gain–of–3D migration function, which correlated positively with formation of podosome rosettes. In conclusion, spatial organization of podosomes as large rosettes, proteolytic degradation of extracellular matrix, and 3D migration appeared to be functionally linked and regulated by Hck in macrophages. Hck, as the first protein combining a phagocyte-limited expression with a role in 3D migration, could be a target for new anti-inflammatory and antitumor molecules.

Introduction

Phagocytes constitute the first line of host defense against microorganisms.1,2 To reach an infectious site, they transmigrate through the endothelial wall, basal membranes, and connective tissues and infiltrate the damaged organ to affect host defense and tissue repair.3 Nevertheless, phagocytes have not only friend but also foe functions.4,5 In several pathologic states, including chronic inflammatory6,7 and neurodegenerative diseases8 or atherosclerosis,9-11 phagocyte-dependent tissue lesions often occur. In addition, it has been established that the presence of macrophages within tumors is a sign of a poor prognosis as they enhance angiogenesis and metastases (see Mantovani et al12 ; Condeelis and Pollard13 ; and Balkwill et al14 for reviews). In contrast, T-cell infiltration into tumors is often associated with a more positive prognosis.15 Therefore it is becoming a challenge to specifically control tissue infiltration of macrophages without affecting lymphocyte migration. By targeting macrophage migration-related molecules, new anti-inflammatory and antitumor-based drugs could be developed.16,17 However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in macrophage migration are poorly understood.

Phagocyte migration has been studied mostly in vitro in 2 dimensions (2D) in response to chemotactic factors. In these experiments, cells are plated on either plastic or glass coverslips, coated or not with matrix proteins. However, in vivo, phagocyte transendothelial migration and infiltration through tissue involve primarily 3-dimensional (3D) regulation. Transendothelial migration proceeds through either a paracellular or a transcellular route involving several types of adhesion proteins and signaling pathways (for a review see, Ley et al3 ). In contrast, the mechanisms underlying phagocyte migration in 3D through connective tissue are poorly understood. The available data on cell migration mechanisms through extracellular matrices have been obtained mostly with invasive tumor cells. Depending on the cell line and the extracellular matrix studied, tumor cells perform a protease-dependent and/or -independent transmatrix migration.18-20 In the absence of proteolytic matrix remodeling, the migration of tumor cells depends on their ability to glide and squeeze through gaps and trails present in connective tissues. The few 3D-migration studies performed on lymphocytes and dendritic cells suggest that these cells migrate in a proteolytic- and integrin-independent fashion.21,22 Transmatrix migration of the macrophage cell line U937 also proceeds through a nonproteolytic and round-shape migration mechanism,20 however the relevance of these cells to primary macrophages or tumor cells is unclear. Recently, the recruitment of macrophages in an aortic aneurysm model has been linked to the dependence of matrix metalloproteinase-9.23 Thus, many questions remain regarding the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in phagocyte migration especially through extracellular matrix (ECM) barriers in vitro and in vivo.

Src-family protein tyrosine kinases are involved in the invasive capacity of tumor cells.24,25 The Src-family protein tyrosine kinases, which are expressed predominantly in myeloid leukocytes, Hck, Fgr, and Lyn, regulate phagocyte migration and degranulation as described mostly using double and triple knockout mice.26 However, the specific roles of each kinase have not yet been elucidated. Hck is expressed as 2 isoforms,27 p59Hck is associated with the plasma membrane where it triggers the formation of protrusions,28,29 and p61Hck is associated with the membrane of lysosomes that contribute to the formation of podosome rosettes.28,30 Interestingly, podosomes are adhesion structures with proteolytic properties toward the extracellular matrix31,32 that are constitutively present in monocyte-derived cells. In contrast, neutrophils do not exhibit regular podosomes.33 Although the precise function of these actin-rich structures is not yet established, that of invadopodia, which are podosome-like structures present in tumor cells, has been implicated in cancer cell invasion and metastasis.34 In the present work, we examined the specific role played by Hck in macrophage 3D migration, as this kinase presents the advantage to be specifically expressed in phagocytes and thereby constitutes a potential target for pharmacologic blockade of macrophage migration. We report that Hck−/− macrophages form fewer podosome rosettes and have impaired ability to degrade ECM, resulting in altered trans-matrix migration in vitro and tissue invasion in vivo.

Methods

Mice

C57Bl6/J wild-type mice were purchased from Charles River Inc. Hck−/− mice, backcrossed onto the C57Bl6/J background, were previously characterized.35 All experiments were performed according to animal protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use committee of the Institut de Pharmacologie et de Biologie Structurale.

Peritoneal inflammation model

Peritoneal injections of 0.5 mL of thioglycolate 4% Brewer (Sigma) or saline buffer were performed in 6- to 12-week-old female mice. Twenty-four or 72 hours after injection, abdominal cavities were washed. Cytospin slides with peritoneal cells were stained with May-Grünwald/Giemsa (RAL) and neutrophils and macrophages were counted.

Histologic analysis

Tissue samples from anterior abdominal wall omentum from wild-type (wt) and Hck−/− mice were taken, fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution (Sigma), embedded in paraffin, and prepared for immunohistochemistry as detailed in supplemental Methods (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Isolation and culture of BMDMs

Bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and tibias and cultured (1.3 × 107/dish; Bioscience Inc) in complete medium (RPMI 1640/10% fetal calf serum [FCS]/1% l-glutamine; Invitrogen) containing 20 ng/mL recombinant murine macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rmM-CSF; Immunotools). After 7 days, adherent bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were harvested with 5 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)/10mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (pH 7.4), resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing 1% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, and 10 ng/mL rmM-CSF, and counted.

Immunoblot analysis

Total cell lysates from wt and Hck−/− BMDMs were subjected to immunoblot analysis as described in supplemental Methods.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis

BMDMs (1 × 106) were incubated with F4/80 antibody (clone CI:A3-1, 1:100; AbD Serotec) in PBS/1% FCS for 1 hour at 4°C, washed, and incubated with secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated goat anti–rat antibody (Cedarlane CLCC 40401) or directly labeled with FITC-conjugated anti–mouse CD11b antibody (Immunotools). Cells were washed twice and analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur using the CellQuestPro software. Background staining was assessed by omitting the primary antibody.

M1/M2 transcriptional profile of BMDMs

RNA was extracted from wt and Hck−/− BMDMs using QIAGEN kit and treated with RNase-free DNase (QIAGEN). The reverse transcription (Superscript II; Invitrogen) of 10 ng of RNA was performed with an oligo(dT) primer. The primers for tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-12p40 (IL-12p40), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), mannose receptor (MR), arginase, Ym1/2, and β-actin were designed using the primer3 tool available at the following website: http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3 as previously described.36,37 Reverse transcriptase was omitted in negative controls. The fold change in target gene cDNA relative to the β-actin endogenous control was determined with the following formulas: fold change = 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔΔCt = (CtTarget − CtActin)stimulated − (CtTarget − CtActin)unstimulated. Ct values were defined as the cycle numbers at which the fluorescence signals were detected38

Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cell lines

Constitutively active (HckY501For Hckca) mutants stably expressed in mouse embryonic fibroblast 3T3 (MEF-3T3) Tet-Off cells (Clontech) have been previously described.30,39 The clones used in this study expressed p59Hckca–green fluorescent protein (GFP) or p61Hckca-GFP or p59 Hckca-GFP and p61Hckca-GFP clones A and B. These cells optimally expressed Hck constructs after 7 days in doxycycline-free culture medium. Hck-negative MEF-3T3 Tet-Off (parental mouse embryonic fibroblasts [MEFs]) were used as a negative control.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

BMDMs (1.5 × 105) were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips (10 μg/mL; Sigma) for 24 hours. Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde (3.7%; Sigma), permeabilized with Triton X-100 (0.1%; Sigma), as previously described,29,30 and stained with antivinculin antibody (clone HVin-1, dilution 1/300; Sigma) followed by FITC-conjugated goat anti–mouse immunoglobulin G (1/500; Coger) and Texas red–coupled phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). For labeling of cell surface matrix metalloprotease 2 (MMP2) and membrane type 1 matrix metalloprotease (MT1-MMP), cells were incubated on ice for 30 minutes with anti-MMP2 (clone VB3, 1/100; Calbiochem) or MT1-MMP (1/100; from Marie Christine Rio, IGBMC, Illkirch, France) monoclonal antibodies in PBS containing 10% FCS before fixation. Antibodies were detected with Alexa546-conjugated goat antibodies (Molecular Probes). MEF-3T3 cells (7 × 103) were allowed to adhere on glass coverslips, fixed, permeabilized, and stained as previously described.30 Slides were visualized with a Leica DM-RB fluorescence microscope.

Matrix degradation assay

Coverslips were coated with 0.2 mg/mL FITC coupled-gelatin (Molecular Probes) as previously described.30 BMDMs (1.5 × 105) were cultured for 24 hours on gelatin-FITC, fixed, processed for F-actin staining, and observed as described above. Quantification of matrix degradation was assessed by measuring the pixels of total cell surface and the pixels of gelatin-FITC degradation area using Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems). The percentage of degradation corresponds to the number of pixels of degradation for 100 pixels of cell surface. Areas corresponding to 100 cells were quantified for each condition in 7 separated experiments.

LysoTracker loading

BMDMs cultured on gelatin-FITC were incubated with the acidotropic dye LysoTracker Red DND-99 (1:1000; Molecular Probes) in RPMI 1640 for 30 minutes. Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes and F-actin stained with Alexa350-coupled phalloidin (Molecular Probes).

3D-migration assays

Transwell assays.

Migration assays were performed in 24-transwells Matrigel Invasion Chambers (8-μm pores; BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, MEF3T3 cells were starved overnight and 2.5 × 104 cells seeded in the upper chambers. The lower chamber was filled with 750 μL of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% FCS, 1% glutamine. After 24 hours, cells in the upper chamber were discarded and migrated cells were counted. Experiments were performed in triplicates with 2 independent clones of each Hck construct.

BMDMs were starved for 3 hours. Lower and upper chambers were filled with RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and 50 ng/mL rmM-CSF or 1% FCS and 10 ng/mL rmM-CSF, respectively. For homemade Matrigel assays, 100 μL of 9.3 mg/mL Matrigel (BD Biosciences) was poured in 24 transwells (8-μm pores), polymerized for 30 minutes at 37°C, and rehydrated for 3 hours with RPMI 1640 medium; the Matrigel matrix thickness was measured with MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices) after setting of the top and the bottom of the matrix: 1.72 (± 0.05 mm; n = 3). BMDMs (5 × 104) were seeded in the upper chamber and after 24 hours of migration z-series of images were acquired at the surface of the Matrigel and at several depths (until 400 μm, 30-μm intervals) into the matrix. Cell migration was measured by dividing the number of cells that invaded the Matrigel matrix by the total cell number. In some experiments, a cocktail of protease inhibitors consisting of 0.1μM aprotinin (Sigma), 0.1μM pepstatin A (Sigma), 0.1μM leupeptin (Sigma), 5μM E-64c (Peptides International), 0.25μM GM6001 (Calbiochem)20 was added in the upper and the lower chambers. Vehicle was loaded as a control. The cell viability was assessed by quantification of trypan blue exclusion.

3D-random migration analysis.

BMDMs (105) suspended in 100 μL of Matrigel at 4°C were plated on glass-based dishes, polymerized for 30 minutes at 37°C, and incubated with RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, and 50 ng/mL rmM-CSF. During recording, cells were kept at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. 3D migration was recorded with the 20× objective of an automated Leica DMIRBE microscope equipped with a CoolSnapEz Camera (Roper Scientific) for 10 hours. Z stacks were acquired every 3 minutes between 400 and 700 μm above the glass surface. Migrating cells were tracked from projected stacks to analyze velocity and persistence over time with MetaMorph 6 software.

2D migration assays

Scraped area replenishment assay.

A confluent monolayer of BMDMs was scraped with a small cell scraper. Replenishment of the scraped area was quantified after 3.5 and 7 hours of culture with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Transwell assay.

Uncoated-8 μm porous transwells (BD Biosciences) and fibronectin-coated transwells were used. Cells were serum starved for 3 hours and the migration assay was carried out for 6 hours. Lower and upper chambers were filled and cell migration quantified as described for transwell 3D-migration assay.

Random migration analysis.

BMDMs were seeded on glass-based dishes (Labtek, Fisher Scientific) or Matrigel (diluted 1/30 in RPMI)–coated glass dishes in complete medium supplemented by 10 ng/mL rmM-CSF. Two-dimensional (2D) migration was recorded every 5 minutes during 5 hours with the 20 × objective of an automated Leica DMIRBE microscope equipped with a CoolSnapEz camera (Roper Scientific). Cells were tracked using MetaMorph 6 software for velocity analysis.

Scanning electron microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy observations of BMDMs on Matrigel matrix were performed as previously described40 ; see supplemental Methods for details.

Gelatin zymography

wt and Hck−/− BMDMs were cultured overnight on fibronectin; cell extracts and supernatants were subjected to zymography assay as detailed in supplemental Methods.

Statistics

All data in the text and figures are expressed as mean (± SEM) and 2-way analysis of variance statistical analyses were carried out with SigmaStat 3.5 software (Systat Software). A P value of less than .05 was considered significant (*P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001).

Results

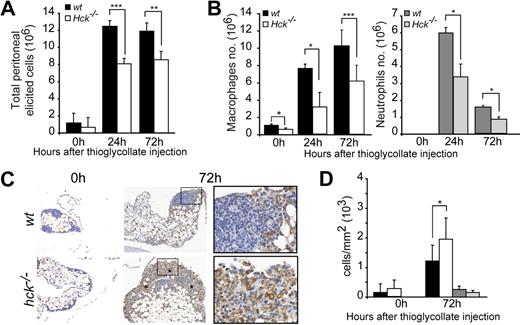

Hck deficiency results in a defect of phagocyte recruitment in the peritoneal cavity

The effect of Hck deficiency on leukocyte migration was evaluated in a peritonitis model induced by an intraperitoneal injection of the inflammatory agent thioglycollate.41 At 24 and 72 hours after thioglycolate injection, the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the peritoneal cavity of Hck−/− mice was significantly reduced compared with wt littermates (Figure 1A). Macrophage and neutrophil infiltration into the peritoneal cavity were affected in Hck−/− mice at 24 and 72 hours (Figure 1B).

Phagocyte recruitment in the peritoneal cavity is inhibited in Hck−/− mice. (A) Total inflammatory cell recruitment in wt and Hck−/− mice after thioglycollate injection in the peritoneal cavity (n = 4-10 mice per group). (B) Recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils is decreased in Hck−/− mice 24 and 72 hours after thioglycollate injection (n = 3). At 0 hours, neutrophils are absent in the peritoneal cavity and resident macrophages are more numerous in wt mice. (C) Immunohistochemistry of macrophages (F4/80 antibodies) performed before and 72 hours after thioglycollate injection. Micrographs show a representative experiment of 3; macrophages are accumulating in peritoneal tissue of Hck−/− mice and no apoptotic cell is noticed. Original magnification ×100 (insets: ×400). Asterisks indicate areas of macrophage accumulation. (D) Quantification of macrophage and neutrophil distribution in peritoneal tissue from wt and Hck−/− mice (expressed as the number of immunostained cells/mm2 of peritoneal tissue). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Phagocyte recruitment in the peritoneal cavity is inhibited in Hck−/− mice. (A) Total inflammatory cell recruitment in wt and Hck−/− mice after thioglycollate injection in the peritoneal cavity (n = 4-10 mice per group). (B) Recruitment of macrophages and neutrophils is decreased in Hck−/− mice 24 and 72 hours after thioglycollate injection (n = 3). At 0 hours, neutrophils are absent in the peritoneal cavity and resident macrophages are more numerous in wt mice. (C) Immunohistochemistry of macrophages (F4/80 antibodies) performed before and 72 hours after thioglycollate injection. Micrographs show a representative experiment of 3; macrophages are accumulating in peritoneal tissue of Hck−/− mice and no apoptotic cell is noticed. Original magnification ×100 (insets: ×400). Asterisks indicate areas of macrophage accumulation. (D) Quantification of macrophage and neutrophil distribution in peritoneal tissue from wt and Hck−/− mice (expressed as the number of immunostained cells/mm2 of peritoneal tissue). *P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

We also noticed that the number of resident macrophages in the peritoneum was lower in Hck−/− mice (Hck−/−: 0.67 × 106 ± 0.13) compared with wt (1.16 × 106 ± 0.15; n = 5; P = .001). To further examine this point, bronchoalveolar lavages that consisted mostly of resident macrophages (> 94%) were performed. Compared with wt mice, the total cell number in bronchoalveolar lavages was decreased by 52% in Hck−/− mice (wt: 8.6 × 104 ± 0.9 vs Hck−/−: 4.1 × 104 ± 0.96; n = 3; P = .006).

The mechanisms by which Hck deficiency could decrease phagocyte recruitment into the peritoneal cavity were examined. First, Hck deficiency may inhibit the production of circulating phagocytes. However, as previously reported,42 we found that peripheral blood white cell counts including monocyte, neutrophil, and lymphocyte of 8- to 12-week-old wt and Hck−/− mice were similar (data not shown), indicating that reduced phagocyte recruitment is not the result of impaired hematopoiesis. Second, a possible defect in transconnective tissue migration was examined. The peritoneal omentum was harvested from the 2 genotypes in physiologic and inflammatory conditions and immunohistochemically stained to distinguish macrophages and neutrophils (Figure 1C and data not shown). At 72 hours after thioglycollate injection, the number of macrophages that accumulated in the peritoneal tissue was significantly higher in Hck−/− compared with wt mice and neutrophils are still present (Figure 1D). Collagen distribution and content in the peritoneal tissue of wt and Hck−/− mice were similar and not altered by thioglycollate stimulation as detected by Masson trichrome staining (data not shown). Third, endothelial transmigration of leukocytes was examined in vivo as described.43 A diapedesis defect is characterized by accumulation of leukocytes on the endothelial surface of vessels, but as shown in supplemental Figure 1, leukocytes were not adhering on the vascular endothelium in the 2 genotypes (wt: 2.17 ± 3.4 vs Hck−/−: 1.35 ± 2.3 leukocytes/10−3 mm2 of vessel section, P = .41). Therefore, the defective recruitment of Hck−/− macrophages in the peritoneal cavity does not result from defective transendothelial migration, supporting a previous report showing that vascular extravasation is functional in Hck−/− mice.44

These results indicate that Hck−/− macrophages, which accumulate in tissue in inflammatory conditions but do not infiltrate the peritoneal cavity, are defective for migration from the connective tissue matrix into the peritoneal cavity.

Defective 3D but not 2D migration in Hck−/− macrophages

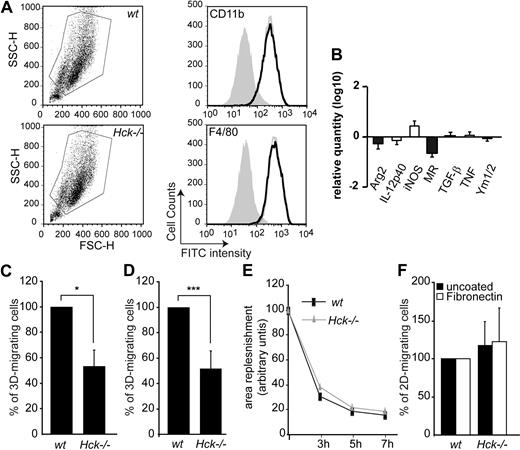

To examine whether altered in vivo recruitment of phagocytes reflects a defect in cell migration, we examined the transmatrix migration capacity of bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) from wt and Hck−/− mice. First, we controlled that identical populations of BMDMs were obtained from the 2 genotypes using standard 2-parameter forward/side scatter (FSC/SSC) flow cytometric analysis (Figure 2A) and that they expressed the 2 macrophage markers CD11b and F4/80 at the same level (Figure 2A). Because the expression of these markers is known to increase progressively during in vitro BMDM differentiation,45 these results indicate that Hck−/− cells reach the same maturation stage as wt cells.

Hck is required for 3- but not 2-dimensional macrophage migration. (A) The gates used for flow cytometry sorting of wt or Hck−/− CD11b+ and F4/80+ BMDMs. Hck−/− BMDMs (gray open histograms) express the same levels as wt (black open histograms) of the differentiation markers CD11b and F4/80 antigens. Closed histograms represent cells alone. (B) Log10 expression levels of genes in resting wt and Hck−/− BMDMs in M1 (□) or M2 (■) polarization. Results are expressed as the ratio of the expression level in Hck−/− BMDMs versus wt BMDMs. (C-D) Defective migration of Hck−/− BMDMs through Matrigel matrix. (C) BMDMs were cultured on commercial Matrigel transwells for 24 hours and cells that reached the lower face of the membrane were counted. Mean value of migrating wt cells (860 ± 723 cells; n = 3) was set arbitrarily to 100%. (D) Quantification of 3D cell migration experiments performed in triplicate. Mean value of migrating wt cells (38% ± 14.3%) was set arbitrarily to 100% (n = 4). (E-F) BMDMs from wt and Hck−/− mice have similar 2D-migration capacity tested with 2 in vitro assays. (E) Scraped area replenishment assay. Replenishment of the scraped area was measured at the indicated time points using the ImageJ software. (F) wt and Hck−/− BMDM 2D-migration through uncoated or fibronectin-coated transwells. BMDMs that reached the lower face of transwells were counted. Mean value of migrating cells (n = 3) was set arbitrarily to 100%; *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Hck is required for 3- but not 2-dimensional macrophage migration. (A) The gates used for flow cytometry sorting of wt or Hck−/− CD11b+ and F4/80+ BMDMs. Hck−/− BMDMs (gray open histograms) express the same levels as wt (black open histograms) of the differentiation markers CD11b and F4/80 antigens. Closed histograms represent cells alone. (B) Log10 expression levels of genes in resting wt and Hck−/− BMDMs in M1 (□) or M2 (■) polarization. Results are expressed as the ratio of the expression level in Hck−/− BMDMs versus wt BMDMs. (C-D) Defective migration of Hck−/− BMDMs through Matrigel matrix. (C) BMDMs were cultured on commercial Matrigel transwells for 24 hours and cells that reached the lower face of the membrane were counted. Mean value of migrating wt cells (860 ± 723 cells; n = 3) was set arbitrarily to 100%. (D) Quantification of 3D cell migration experiments performed in triplicate. Mean value of migrating wt cells (38% ± 14.3%) was set arbitrarily to 100% (n = 4). (E-F) BMDMs from wt and Hck−/− mice have similar 2D-migration capacity tested with 2 in vitro assays. (E) Scraped area replenishment assay. Replenishment of the scraped area was measured at the indicated time points using the ImageJ software. (F) wt and Hck−/− BMDM 2D-migration through uncoated or fibronectin-coated transwells. BMDMs that reached the lower face of transwells were counted. Mean value of migrating cells (n = 3) was set arbitrarily to 100%; *P < .05; ***P < .001.

Because a bias in M1/M2 differentiation has been recently described in macrophages from double Lyn and Hck knockout mice,46 a combination of biomarkers was used to define macrophage polarization. The M1 pattern is characterized by the expression of iNOS, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as IL-12 and TNF, whereas the M2 profile, by arginase, MR, TGFβ-1, and Ym1/2.38 Comparing BMDMs from wt or Hck−/− mice, the expression of the different markers tested was not significantly modulated (Figure 2B).

To examine the 3D-migration capacity of Hck−/− BMDMs, transwells coated with Matrigel, an extracellular matrix containing a heterogeneous mixture of proteins produced by a mouse sarcoma cell line grown in vivo, were used. Transwells are separated by a membrane with 8-μm pores occluded by a thin layer of Matrigel. Compared with wt BMDMs, the number of Hck−/− BMDMs in the lower side of the chamber was significantly decreased (Figure 2C). We observed no significant morphologic differences between wt and Hck−/− BMDMs during spreading on Matrigel or purified ECM proteins (fibronectin, fibrinogen, or gelatin; data not shown), supporting previous observations47 and suggesting that defective 3D migration was not the result of altered cell spreading.

Next, we tested the 3D-migration capacity of BMDMs in a high Matrigel density (30-fold more concentrated than the commercial preparation) layered in transwells to form a thick layer of matrix (> 1.5 mm). Our objective was to test whether the migration defect of Hck−/− BMDMs could be enhanced in Matrigel with a higher density, to observe the cell morphology and to measure the cell migration velocity inside the matrix. After 24 hours, z-series of images from the top of the Matrigel layer to the bottom were collected (supplemental Video 1) and cells were counted. The number of Matrigel-infiltrated Hck−/− BMDMs was significantly reduced by 40% compared with wt BMDMs (Figure 2D) to a similar extent as commercial Matrigel (Figure 2C), indicating that trans-matrix migration was not further affected in a high-density matrix. When wt and Hck−/− cells were examined inside Matrigel by time-lapse microscopy, they exhibited a very similar morphology with an elongated cell shape and plasma membrane protrusions (supplemental Video 2). Moreover, we found that the 3D-migration velocity was significantly reduced in Hck−/− BMDMs (0.316 ± 0.015 μm/minute) compared with wt cells (0.405 ± 0.014 μm/minute; P < .001). In conclusion, fewer Hck−/− BMDMs are entering into Matrigel, and those that do migrate more slowly than wt cells.

The 2D-migration capacity of BMDMs was also examined using scraped area replenishment assay and migration on fibronectin-coated or uncoated transwells. The ability of wt and mutant macrophages to replenish the scraped area (Figure 2E) and to migrate on fibronectin-coated or uncoated transwells (Figure 2F) were similar. We also observed no significant difference with 2D velocities of macrophages migrating randomly on uncoated (wt: 1.30 ± 0.06 μm/minute; Hck−/− macrophages: 1.45 ± 0.07 μm/minute) or Matrigel-coated (wt: 0.643 ± 0.02; Hck−/−: 0.83 ± 0.02 μm/minute) glass coverslips. These results indicate that the 3D-migration capacity of Hck−/− macrophages is decreased, whereas the 2D migration is not affected.

Cooperation of Hck isoforms is required for cell transmatrix migration

As Hck appeared to be involved in 3D-migration, gain-of-function experiments were designed to examine whether Hck expression is sufficient to provide a 3D-migration capacity to cells that do not naturally express Hck and do not migrate inside matrix. MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cells were stably and conditionally (Tet-Off) transfected with constitutively active variants of Hck (Hckca) in fusion with GFP.30,39,48 Cell clones were chosen on 2 criteria: Hck expression level quantitatively comparable with phagocytes and characteristic Hck phenotypes, membrane protrusions, and podosome rosettes (supplemental Figure 3).29,30 Compared with parental MEF-3T3 cells, cells coexpressing the 2 Hck isoforms acquired the ability to migrate through Matrigel (Figure 3A), whereas their 2D-migration capacity was not modified (parental MEFs: 0.59 ± 0.03, MEF-p59/p61Hckca: 0.67 ± 0.02 μm/minute; mean of 122 cells ± SD and 183 cells, respectively). Next, we examined the respective role of each isoform in the 3D-migration experiments. Again, cell clones were chosen on characteristic Hck phenotypes, membrane protrusions for p59Hckca- or podosome rosettes for p61Hckca-expressing cells (Poincloux et al48 and supplemental Figure 3). Neither MEF-p59Hckca nor MEF-p61Hckca entered into the matrix (Figure 3A).

Ectopic expression of Hck provides fibroblasts the capacity to migrate through Matrigel. (A) Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells expressing Hck isoforms together or separately that migrated through Matrigel transwells were counted as in the legend of Figure 2C. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of 3 experiments; parental cells were Hck-negative Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells. (B) Photomicrograph showing nuclei (DAPI [4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole]: blue), p59/61Hckca-GFP (green), and F-actin (phalloidin–tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate: red); arrows indicate podosome rosettes located at the pore exit (dotted circles) of the transwell. p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cells had more podosome rosettes after transmigration (24 hours, cells examined at the bottom face of the 8-μm pore transwells) than before (0 hours, cells examined at the top of transwells). (C) The cell migration capacity through Matrigel is correlated to the rate of podosome rosettes. The percentage of cells with podosome rosettes was quantified in 2 p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cell clones (clones A and B; left panel) and invasion assays were performed in triplicate in 4 separate experiments (right panel); ***P < .001.

Ectopic expression of Hck provides fibroblasts the capacity to migrate through Matrigel. (A) Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells expressing Hck isoforms together or separately that migrated through Matrigel transwells were counted as in the legend of Figure 2C. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of 3 experiments; parental cells were Hck-negative Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells. (B) Photomicrograph showing nuclei (DAPI [4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole]: blue), p59/61Hckca-GFP (green), and F-actin (phalloidin–tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate: red); arrows indicate podosome rosettes located at the pore exit (dotted circles) of the transwell. p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cells had more podosome rosettes after transmigration (24 hours, cells examined at the bottom face of the 8-μm pore transwells) than before (0 hours, cells examined at the top of transwells). (C) The cell migration capacity through Matrigel is correlated to the rate of podosome rosettes. The percentage of cells with podosome rosettes was quantified in 2 p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cell clones (clones A and B; left panel) and invasion assays were performed in triplicate in 4 separate experiments (right panel); ***P < .001.

Invadopodia, the tumoral cell counterpart of podosomes, are involved in ECM degradation and probably in tissue invasion.31,34 Interestingly, we noticed that MEF-p59/p61Hckca cells reaching the lower chamber, as attested by the presence of the nuclei still inside the pores, often formed large rosettes of podosomes at the pore exit (Figure 3B arrows). In addition, MEF-p59/p61Hckca cells found in the lower chamber of transwells that had migrated through Matrigel (24-hour migration) had 2-fold more podosome rosettes than cells seeded at the top of the Matrigel layer at the beginning of the experiment (Figure 3B). These results suggested that the presence of podosome rosettes correlates with the 3D-migration ability. Actually, we observed that clone B, with a lower percentage of cells with podosome rosettes than clone A (Figure 3C left panel), had a low migration capacity (Figure 3C right panel), demonstrating a positive correlation between the cell ability to form podosome rosettes and the transmatrix migration function. As MEF-p61Hckca cells exhibited the same percentage of podosome rosettes than MEF-p59/p61Hckca clone A but were unable to migrate through Matrigel (Figure 3A), we concluded that the presence of rosettes of podosomes and that expression of the 2 Hck isoforms are required for transmatrix migration.

Hck−/− BMDMs failed to form large rosettes of podosomes

Because the presence of rosettes of podosomes correlated with 3D- migration in Hck-expressing fibroblasts, we examined these structures in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs.

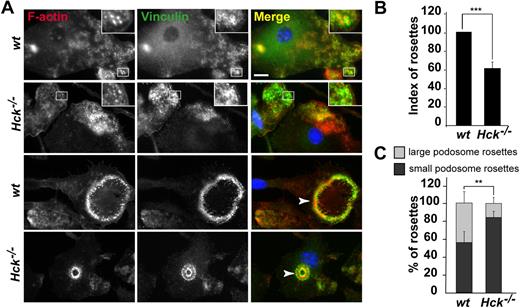

On glass coverslips, adherent macrophages spontaneously formed individual podosomes but not rosettes. The number and distribution of podosomes were not different between BMDMs from wt and Hck−/− mice (data not shown). We then plated BMDMs on several purified matrix proteins. We noticed that BMDMs spontaneously arranged their podosomes as rosettes more frequently on fibronectin (Figure 4) or gelatin (Figure 5) than on fibrinogen-coated coverslips (data not shown). As shown in Figure 4A, BMDMs from wt and Hck−/− mice layered on fibronectin had scattered individual podosomes with the characteristic ring of vinculin surrounding the F-actin core (top 2 panels, insets) and podosomes organized as rosettes (bottom 2 panels). Rosettes of podosomes in wt BMDMs were structured as small (≤ 10 μm) and large (≥ 20 μm) diameters. In Hck−/− cells, the index of podosome rosettes (number of rosettes in 100 cells) was reduced by 40% compared with wt BMDMs (Figure 4B) and small rosettes were predominant (Figure 4A,C).

Hck−/− BMDMs do not form large podosome rosettes. BMDMs were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 24 hours, fixed, and permeabilized. F-actin was stained with Texas red–coupled phalloidin; vinculin, with primary and FITC-coupled secondary antibodies; and nuclei, with DAPI, and cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy. (A top 2 panels) Characteristic podosomes are present in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs with an actin core surrounded by a ring of vinculin (insets). (Bottom 2 panels) wt BMDMs form a large podosome rosette (arrowhead on the Merge image); Hck−/− BMDMs do not form large, but small, podosome rosettes (arrowhead; scale bar represents 10 μm; magnification ×100). (B) Quantification of podosome rosettes in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs. Rosettes were counted in at least 100 cells in duplicate (n = 4). (C) Quantification of small and large rosettes in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs. Hck−/− BMDMs preferentially form small podosome rosettes (n = 4); **P < .01; ***P < .001.

Hck−/− BMDMs do not form large podosome rosettes. BMDMs were seeded on fibronectin-coated coverslips for 24 hours, fixed, and permeabilized. F-actin was stained with Texas red–coupled phalloidin; vinculin, with primary and FITC-coupled secondary antibodies; and nuclei, with DAPI, and cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy. (A top 2 panels) Characteristic podosomes are present in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs with an actin core surrounded by a ring of vinculin (insets). (Bottom 2 panels) wt BMDMs form a large podosome rosette (arrowhead on the Merge image); Hck−/− BMDMs do not form large, but small, podosome rosettes (arrowhead; scale bar represents 10 μm; magnification ×100). (B) Quantification of podosome rosettes in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs. Rosettes were counted in at least 100 cells in duplicate (n = 4). (C) Quantification of small and large rosettes in wt and Hck−/− BMDMs. Hck−/− BMDMs preferentially form small podosome rosettes (n = 4); **P < .01; ***P < .001.

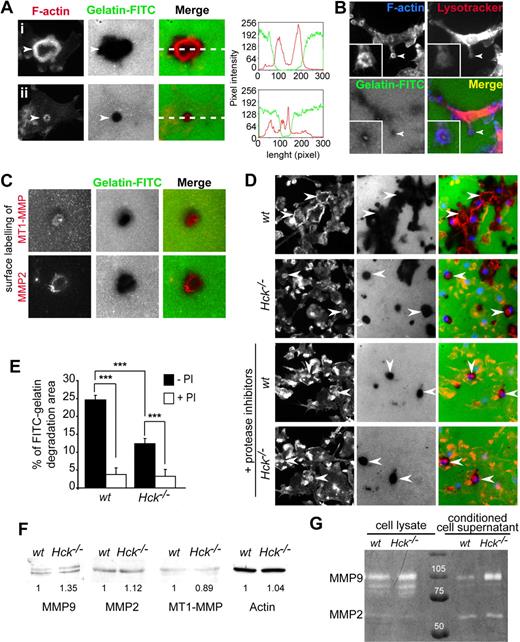

Podosome rosette–associated ECM degradation is a protease-dependent process altered in Hck−/− BMDMs. (A) Podosome rosettes exhibit ECM degradation activity. BMDMs were seeded on FITC-coupled gelatin-coated coverslips. After 24 hours, cells were fixed and stained for F-actin and microscopically examined. Large degradation area is formed underneath large podosome rosettes (i). In contrast, small degradation area is observed underneath small podosome rosettes (ii). Measurements of fluorescent intensities along the white dashed line depicted in subpanels i and ii in the merged image shows increase of intensities of F-actin (red line) correlating with loss of fluorescent intensity of the gelatin (green line). (B) Podosome rosette is a site for LysoTracker accumulation. (C) MT1-MMP and MMP2 localize at sites of gelatin-FITC degradation. BMDMs were subjected to cell surface labeling with MT1-MMP and MMP2 antibodies. (D-E) BMDMs were seeded on FITC-coupled gelatin-coated coverslips and incubated overnight in the presence or absence of a protease inhibitor cocktail, then fixed and stained for F-actin and nuclei and microscopically examined for quantification. (D top 2 panels) wt BMDMs form large podosome rosettes associated with large areas of gelatin-FITC degradation (arrowheads). Hck−/− BMDMs form small podosome rosettes and degrade small gelatin areas (arrowheads). (Bottom 2 panels) The same experiments performed in the presence of protease inhibitors (PI), which significantly block matrix degradation (scale bar represents 10 μm; magnification ×40). (E) Quantification of FITC-coupled gelatin degradation by BMDMs in the presence and in the absence of protease inhibitors. The percentage of degradation corresponds to the number of pixels of degradation for 100 pixels of cell surface. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8) of FITC-gelatin degradation areas. (F) wt and Hck−/− BMDMs express similar levels of MMP2, MMP9, and MT1-MMP. Immunoblot analysis performed on BMDM cell lysates for MMP9 (92 kDa), MMP2 (72 kDa), MT1-MMP (64 kDa), and actin (46 kDa). (G) Hck−/− BMDMs are not defective in MMP9 and MMP2 activity and release. Gelatin zymograph of BMDM cell lysates or conditioned media collected from cells adhering on fibronectin.

Podosome rosette–associated ECM degradation is a protease-dependent process altered in Hck−/− BMDMs. (A) Podosome rosettes exhibit ECM degradation activity. BMDMs were seeded on FITC-coupled gelatin-coated coverslips. After 24 hours, cells were fixed and stained for F-actin and microscopically examined. Large degradation area is formed underneath large podosome rosettes (i). In contrast, small degradation area is observed underneath small podosome rosettes (ii). Measurements of fluorescent intensities along the white dashed line depicted in subpanels i and ii in the merged image shows increase of intensities of F-actin (red line) correlating with loss of fluorescent intensity of the gelatin (green line). (B) Podosome rosette is a site for LysoTracker accumulation. (C) MT1-MMP and MMP2 localize at sites of gelatin-FITC degradation. BMDMs were subjected to cell surface labeling with MT1-MMP and MMP2 antibodies. (D-E) BMDMs were seeded on FITC-coupled gelatin-coated coverslips and incubated overnight in the presence or absence of a protease inhibitor cocktail, then fixed and stained for F-actin and nuclei and microscopically examined for quantification. (D top 2 panels) wt BMDMs form large podosome rosettes associated with large areas of gelatin-FITC degradation (arrowheads). Hck−/− BMDMs form small podosome rosettes and degrade small gelatin areas (arrowheads). (Bottom 2 panels) The same experiments performed in the presence of protease inhibitors (PI), which significantly block matrix degradation (scale bar represents 10 μm; magnification ×40). (E) Quantification of FITC-coupled gelatin degradation by BMDMs in the presence and in the absence of protease inhibitors. The percentage of degradation corresponds to the number of pixels of degradation for 100 pixels of cell surface. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 8) of FITC-gelatin degradation areas. (F) wt and Hck−/− BMDMs express similar levels of MMP2, MMP9, and MT1-MMP. Immunoblot analysis performed on BMDM cell lysates for MMP9 (92 kDa), MMP2 (72 kDa), MT1-MMP (64 kDa), and actin (46 kDa). (G) Hck−/− BMDMs are not defective in MMP9 and MMP2 activity and release. Gelatin zymograph of BMDM cell lysates or conditioned media collected from cells adhering on fibronectin.

In conclusion, podosome rosettes in Hck−/− BMDMs are significantly fewer and smaller than in the wt counterpart.

ECM degradation and trans-matrix migration of BMDMs are impaired by protease inhibitors

Although the presence and the role of podosome rosettes in macrophages have been poorly documented,49,50 we expected that (1) they mimic podosome reorganization into sealing zones in osteoclasts, the place of acidic pH and efficient extracellular matrix proteolysis, and (2) similarly to Hck-expressing fibroblasts (Figure 3), they are involved in 3D-migration.

First we examined the matrix degradation capacity of podosome rosettes of BMDMs layered on gelatin-FITC–coated glass coverslips for 8 hours. Matrix degradation areas were noticed beneath podosome rosettes that fit with the size and shape of rosettes (highlighted by the linescan, Figure 5A). Several proteases such as matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and MMP-9 have been localized at invadopodia-podosomal structures in several cell types including osteoclasts.31 In BMDMs, MMP-2, MT1-MMP, and LysoTracker, which stains acidic compartments, colocalized with matrix degradation areas (Figure 5B-C).

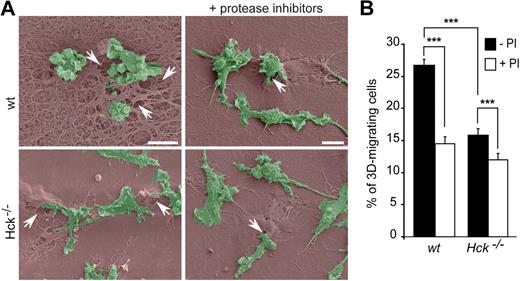

To determine whether the difference in number and size of podosome rosettes between wt and Hck−/− BMDMs (Figure 4) correlated with the ECM degradative capacity, matrix degradation areas were quantified after overnight culture of macrophages on gelatin-FITC. wt BMDMs made larger degradation areas in gelatin-FITC than Hck−/− macrophages (Figure 5D-E). Similarly, when macrophages were seeded on thick Matrigel matrix used to perform 3D-migration experiments, Hck−/− BMDMs had much less degradative activity than wt cells as observed by scanning electron microscopy (Figure 6A, see arrows showing matrix degradation areas beneath the cells entering into the matrix).

Protease-dependent macrophage migration through Matrigel. (A) Scanning electron microscopy images showing wt and Hck−/− BMDMs (green) on thick Matrigel (brown) transwells in the presence or absence of protease inhibitors. Matrigel remodeling (arrows) is more important with wt than Hck−/− BMDMs and is inhibited by protease inhibitors. Images are showing BMDMs infiltrating the matrix and are representative of 3 experiments (scale bar represents 10 μm). (B) Protease inhibitors inhibit both wt and Hck−/− BMDMs migration through Matrigel. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells that migrate through Matrigel (mean ± SEM; n = 4). ***P < .001.

Protease-dependent macrophage migration through Matrigel. (A) Scanning electron microscopy images showing wt and Hck−/− BMDMs (green) on thick Matrigel (brown) transwells in the presence or absence of protease inhibitors. Matrigel remodeling (arrows) is more important with wt than Hck−/− BMDMs and is inhibited by protease inhibitors. Images are showing BMDMs infiltrating the matrix and are representative of 3 experiments (scale bar represents 10 μm). (B) Protease inhibitors inhibit both wt and Hck−/− BMDMs migration through Matrigel. Results are expressed as the percentage of cells that migrate through Matrigel (mean ± SEM; n = 4). ***P < .001.

To investigate the role of proteases in ECM degradation and macrophage trans-matrix migration, we used a cocktail of protease inhibitors described to inhibit protease-dependent matrix invasion by tumor cells.24,51 In the presence of protease inhibitors, the following parameters were decreased: (1) degradation of FITC-coupled gelatin by wt and Hck−/− macrophages (Figure 5D bottom panels and 5E), (2) Matrigel degradation (Figure 6A), and (3) the migration capacity of wt and Hck−/− BMDMs through Matrigel (Figure 6B). The residual migration capacity of macrophages from the 2 genotypes (Figure 6B) could result from the remaining ECM degradation activity observed in Figure 5D and E. Next we examined whether the low matrix degradation capacity of Hck−/− BMDMs could result from altered expression and/or release of matrix-degrading proteases. However, expression of MMP2, MMP9, and MT1-MMP activity and release in the extracellular medium of MMP2 and MMP9 measured by zymography were similar in the 2 genotypes as shown in Figure 5F and G. Therefore, the low capacity of Hck−/− BMDMs to degrade the ECM is likely due to undersized podosome rosettes and not to altered proteolytic activity per se.

These data indicate that wt macrophages form podosome rosettes with matrix proteolytic activity and infiltrate Matrigel in a protease-dependent manner. For comparison, Hck−/− macrophages exhibit a limited capacity to form podosome rosettes, and, consequently, low ECM degradative and transmatrix migration activities. Therefore, Hck is a regulator for the formation of cell structures involved in proteolytic-dependent transmatrix migration of macrophages.

Discussion

Our work provides evidence that Hck is involved in macrophage migration through interstitial tissue in physiologic and pathologic contexts. Hck is required for efficient proteolytic degradation of ECM thanks to the spatial organization of podosomes as large rosettes.

To reach inflammatory sites, monocyte/macrophages have to perform transendothelial diapedesis and migration through interstitial tissues. In a peritonitis model, macrophages barely reached the peritoneal cavity in Hck−/− mice. They accumulated in the peritoneal tissue and no defect in the vascular egress was noticed. To explain the reduced cell infiltration in the peritoneal cavity of Hck−/− mice, it is likely that macrophage migration through interstitial tissue is defective

Consistently, using Matrigel, a mixture of ECM proteins produced in vivo by sarcoma cells that mimic composition of basement membrane, we report that Hck−/− macrophages have an altered transmatrix migration. Gain-of-function experiments performed with MEF-3T3 fibroblasts show that ectopic expression of Hck provides the ability to migrate through Matrigel. Neither hck knockout in macrophages nor Hck expression in fibroblasts affected 2D-migration. Interestingly, recent observations show that cell migration in 2D or 3D activates distinct molecular and cellular mechanisms.52,53 Therefore, Hck appears to play a role specifically in 3D-migration.

We report that trans-matrix migration of BMDMs is a protease-dependent process. This is an important observation as it was generally proposed that leukocytes migrate in a protease-independent manner (for a review, see Friedl and Weigelin22 ). It is possible that leukocyte migration through loose connective tissue could operate without ECM degradation but migration through stiff matrices characterized as anatomic boundaries might require proteases. Actually, it has recently been reported that MMP9 is required in peritoneal infiltration of macrophages elicited by thioglycollate,23 indicating that at least part of the in vivo migration route is protease dependent. Hck−/− macrophages have a reduced capacity to infiltrate the matrix, but the few cells that migrate use a protease-dependent mechanism. Interestingly, we observe that Hck−/− macrophages have a normal expression, activity, and release of proteases dedicated to matrix degradation: MMP-2, MMP-9, and MT1-MMP. Although MMPs, which play a central role in ECM degradation,31 are not affected, we cannot exclude that other proteases implicated in this process would be defective in Hck−/− macrophages. However, it appeared more promising to examine cell structures involved in matrix degradation where proteases, including MMPs, accumulate. In fact, we have shown before that Hck triggers the formation of podosome rosettes with matrix proteolytic activity.30 Now, we report that Hck−/− macrophages form few and undersized podosome rosettes with limited matrix degradation capacity. In contrast, wt macrophages exhibit large areas of proteolysed matrix underneath large and numerous podosome rosettes. Therefore defective formation of podosome rosettes in Hck−/− macrophages likely explains their defective ECM proteolytic activity.

Several lines of evidence obtained in tumor cells show that formation of podosome-like invadopodia with proteolytic activity correlates with tissue invasiveness40 (for review, see Gimona et al32 and Weaver34 ). In addition, we show that podosome rosettes correlated positively with the 3D-migration capacity of Hck-expressing fibroblasts. Consistently, Hck−/− macrophages with undersized podosome rosettes have a reduced transmatrix migration capacity compared with wt cells. Organization of podosomes as rosettes occurs when macrophages are activated,49,50 or in contact with appropriate ECM proteins as described herein. Similarly to bone resorption pits underneath the sealing zone of macrophage-derived osteoclasts, it is likely that matrix degradation capacity is potentiated when podosomes are grouped as rosettes.54 To avoid massive degradation, macrophage migration through tissues should operate without secreting proteases at large in the extracellular medium. Therefore, podosome structures specialized in matrix degradation that are spatially organized as large rosettes by Hck might be the appropriate structures for focal and restrained ECM proteolysis required for 3D-migration of macrophages.

In conclusion, spatial organization of podosomes as large rosettes, proteolytic degradation of ECM, and 3D-migration appeared to be functionally linked and regulated by Hck. Tissue infiltration of macrophages is most of the time related to poor prognosis in cancers as it stimulates both angiogenesis and formation of metastasis.13 Phagocytes also play a deleterious role, by increasing tissue damage during chronic infectious or inflammatory diseases. In light of the results presented in this paper, we propose that Hck could be a good pharmacologic target to inhibit macrophage tissue infiltration, and is, as far as we know, the first protein combining a phagocyte-limited expression with a role in 3D migration.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr M.-C. Prévost for access to the Ultrastructural Microscopy Platform of Institut Pasteur Paris; Emeline Van-Goethem for expertise with the Matrigel matrix setup; Corinne Lorenzo and Plateform TRI Toulouse; Philippe Chavrier, Stefan Linder, Catherine Muller, and Marie-Christine Rio for providing antibodies; M. Waqar Aslam for technical assistance; and Christine Bordier and Etienne Joly for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis.

This work was supported by grants from Association pour la Recherche contre le cancer (ARC) 39-88, CNRS, Institut National du Cancer (INCa), ANR Blanc (I.M.-P.), and National Institutes of Health AI065495 (C.A.L.). N.L.-M. was supported by INCa-ARC; R.P. was supported by a grant from Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer and INCa-ARC.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: C.C. conceived, designed, and analyzed the experiments, performed the experiments on mice and BMDMs, and wrote the paper; V.L.C. and R.P. were in charge of Hck in fibroblasts; T.A.S. performed preparation and analyses of histologic samples; J.-L.M. performed M1/M2 assays; G.T. provided his expertise in handling BMDMs; C.A.L. provided knockout mice and critical reading of the paper; N.L.-M. performed the experiments on mice and BMDMs; and I.M.-P. conceived, designed, and analyzed the experiments.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Isabelle Maridonneau-Parini, IPBS CNRS UMR5089, 205 Route de Narbonne, F-31077 Toulouse, France; e-mail: isabelle.maridonneau-parini@ipbs.fr.

![Figure 3. Ectopic expression of Hck provides fibroblasts the capacity to migrate through Matrigel. (A) Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells expressing Hck isoforms together or separately that migrated through Matrigel transwells were counted as in the legend of Figure 2C. Results are expressed as mean ± SD of 3 experiments; parental cells were Hck-negative Tet-Off MEF-3T3 cells. (B) Photomicrograph showing nuclei (DAPI [4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole]: blue), p59/61Hckca-GFP (green), and F-actin (phalloidin–tetramethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate: red); arrows indicate podosome rosettes located at the pore exit (dotted circles) of the transwell. p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cells had more podosome rosettes after transmigration (24 hours, cells examined at the bottom face of the 8-μm pore transwells) than before (0 hours, cells examined at the top of transwells). (C) The cell migration capacity through Matrigel is correlated to the rate of podosome rosettes. The percentage of cells with podosome rosettes was quantified in 2 p59/61Hckca-MEF-3T3 Tet-Off cell clones (clones A and B; left panel) and invasion assays were performed in triplicate in 4 separate experiments (right panel); ***P < .001.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/115/7/10.1182_blood-2009-04-218735/4/m_zh89990946660003.jpeg?Expires=1769106156&Signature=tVo0WrvJ10V2Euq9pwmpEzRj~fdU1R~aKb8kc9qLvVA3ti~Fh9HOTcJ~uddv1TBoPUVWGY3jIqCsp-U9wIADLN8WBxVvBj7KjTjeaP2r6uelarvVAtinnqzpTiNLLdw0xU2TFWEyMzyBL-W3Ww4hd-a62fr2nLbS2oUuH-T8uWT25YrX5oTyEKacVnLLMl5cG20ZPLyoZT3AIh8XbXQiOQvCrSr7UOaVugPaEohI8uigAzq8YG8qfw8Dt7scYT67LDsw2wZGvs8EQgmFWGFi5d8hNeUjzL9-OHZhOvZkSX49~dwDQOWq1CfaMoz2FqcG3f~APsCY0JMA9Jy8PMmn8Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)