Abstract

Gremlins are mischievous creatures in English folklore, believed to be the cause of otherwise unexplainable breakdowns (the word gremlins is derived from the Old English “gremian” or “gremman,” “to vex”). Gremlin (or Gremlin-1) is also the designation of a secreted protein that is known to regulate bone formation during development. In this issue of Blood, Mitola et al report the novel role of Gremlin as a VEGFR2 agonist1 and the function of the Gremlin protein seems vexing indeed.

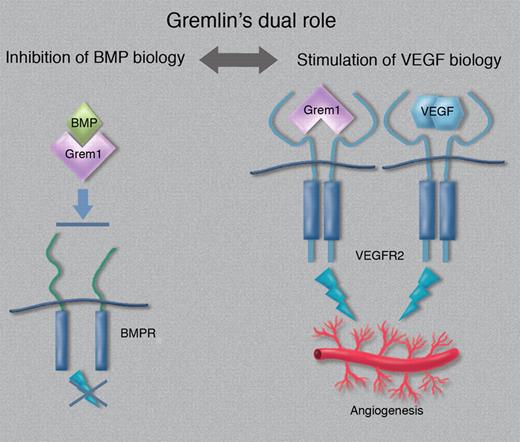

Schematic outline of Gremlin's dual role in tumor biology. Neutralization of BMPs may result in attenuation of suppressive signaling, whereas stimulation of VEGFR2 promotes angiogenesis. (Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.)

Schematic outline of Gremlin's dual role in tumor biology. Neutralization of BMPs may result in attenuation of suppressive signaling, whereas stimulation of VEGFR2 promotes angiogenesis. (Professional illustration by Marie Dauenheimer.)

Gremlin was originally identified as a member of a Xenopus laevis protein family regulating broad processes in growth and development; independently, Gremlin was identified as a rat variant denoted “Drm” (down-regulated in mos-transformed cells).2 The secreted Gremlin proteins have been shown to exert their effects by blocking the function of specific bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs),2 which belong to the transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) superfamily. Gremlin binds to and inhibits the function of BMP2, BMP4, and BMP7, which in turn regulate limb development. In accordance, inactivation of the grem1 gene in mice causes skeletal malformation and increased bone formation whereas overexpression causes inhibition of bone formation and osteopenia.2 Thus, whereas Gremlin plays an important role in bone development, its function, if any, in adult physiology is unknown.

Mitola et al now show that Gremlin binds with high affinity to the important vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor in endothelial cells, VEGF receptor-2 (VEGFR2). Biochemically, Gremlin behaves surprisingly similar to VEGF in its activation of VEGFR2; it induces tyrosine phosphorylation of the receptor, as well as downstream signaling, resulting in endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and formation of angiogenic sprouts.3

From a structural point of view, it is not entirely surprising that Gremlin would bind to VEGFR2. Gremlin and VEGF (as well as TGFβ and platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF]) all share a structural cysteine-knot motif.2,4 The concept that one receptor molecule can bind structurally distinct ligands is also not new. Mitola et al1 show convincingly that Gremlin indeed is a potent and specific VEGFR2 agonist which competes out binding of VEGF in a dose-dependent manner.

However, it is unclear at this point to what extent VEGF and Gremlin overlap biologically. Whereas VEGF/VEGFR2 is tightly linked to angiogenesis, both in physiology and pathology such as in the growth of cancer,3 the biology of Gremlin/VEGFR2 is not obvious and in vivo studies remain to be performed. There is as yet no data that ties Gremlin directly to tumor angiogenesis. Of note, Gremlin is expressed in a range of human cancers (carcinomas of the uterine cervix, lung, ovary, kidney, breast, colon, and pancreas, see Sneddon et al5 ), where it has been suggested to neutralize the negative regulatory role of BMPs in cell proliferation. However, it is important to remember that BMPs can be either stimulatory or inhibitory in human cancer possibly dependent on the expression level and the microenvironment.6

Gremlin binds and activates VEGFR2 efficiently, independent of complex formation with BMPs. In fact, the Gremlin/BMP complex is slightly more active on endothelial cells than Gremlin alone.7 On the other hand, the Gremlin/BMP complex fails to bind to and activate the BMP receptor. Therefore, potentially, Gremlin may not only neutralize negatively regulating BMPs in human cancer,6 but also further enhance tumor growth by stimulating tumor angiogenesis (see figure). Gremlin may regulate tumor angiogenesis also indirectly, through induction of Angiopoietin-1.8

Interestingly, Gremlin has been implicated in chronic fibrotic diseases such as diabetic nephropathy.9 The diabetic kidney is characterized by interstitial fibrosis but also by microangiopathy. Possibly, Gremlin's ability to bind to and activate VEGFR2 could play a role here as well.

Whether we need more vexing players in angiogenesis or not, Gremlin's dual power, negative with regard to BMP biology and positive with regard to VEGF biology, could very well have clinical implications and should be further studied.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. ■

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal