In this issue of Blood, Flood and colleagues show that a single amino acid change in VWF causes artifactually low values for ristocetin cofactor activity (VWF:RCo), illustrating another reason why this test cannot be used uncritically to diagnose von Willebrand disease.

When patients bleed unexpectedly, we try our best to explain why but have to make do with imperfect tools. For example, a diagnosis of von Willebrand disease (VWD) may be considered for a patient with menorrhagia, severe bruising, epistaxis, or postoperative hemorrhage. To diagnose VWD, we depend on laboratory testing of von Willebrand factor (VWF) concentration and function. Antigen measurements (VWF:Ag) are straightforward, but assessing VWF function is not. VWF mediates platelet adhesion at sites of vascular injury by binding to subendothelial connective tissue and to platelet membrane GPIbα. Unfortunately, no practical method has been developed to assay VWF-dependent platelet adhesion in vitro, and we rely instead on a fortuitous side effect of the antibiotic ristocetin.

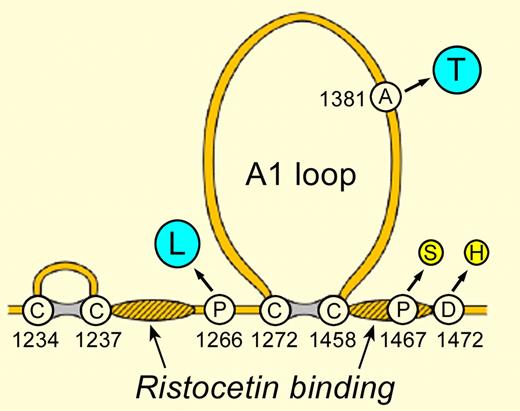

VWF sequence variants that change VWF:RCo. The A1 loop contains the GPIbα binding site. Hatched regions have been implicated in ristocetin binding. The indicated single amino acid substitutions cause either increased (blue) or decreased (yellow) VWF:RCo without an apparent change in VWF hemostatic function.

VWF sequence variants that change VWF:RCo. The A1 loop contains the GPIbα binding site. Hatched regions have been implicated in ristocetin binding. The indicated single amino acid substitutions cause either increased (blue) or decreased (yellow) VWF:RCo without an apparent change in VWF hemostatic function.

Ristocetin cannot be used safely in humans because it binds to VWF, promotes VWF-dependent platelet aggregation, and causes profound thrombocytopenia. Such behavior is unacceptable for a drug, but in 1971, Margaret Howard and Barry Firkin turned it to advantage by devising a simple assay for VWF function based on ristocetin-induced platelet aggregation.1 Almost 40 years later, some form of VWF:RCo assay remains a key test for the diagnosis of VWD in almost all hemostasis laboratories worldwide. However, a normal VWF:RCo is not at all the same as normal VWF-dependent platelet adhesion: the test simply requires ristocetin to bind VWF and activate a cryptic binding site for platelet GPIbα. Therefore, one might expect VWF:RCo to misrepresent the function of VWF if a patient had a selective defect in the binding of VWF to collagen or to ristocetin. In fact, inherited variations in VWF-ristocetin binding prove to be common among subjects misdiagnosed with VWD, especially for persons of African ancestry.

Several studies have observed that, on average, African Americans have a relatively decreased value of VWF:RCo consistent with a heritable change in VWF function. For example, Miller and colleagues reported that the ratio VWF:RCo to VWF:Ag was 18% lower for African Americans than for Caucasians, and the effect was independent of ABO blood type.2 Suspecting that variations of this magnitude might affect the apparent prevalence of VWD, Flood et al look at their patients with VWD and observe that African Americans were greatly overrepresented among patients with VWD type 2M, a subtype of VWD characterized by a decreased VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio. Furthermore, these patients rarely had significant bleeding symptoms. In a series of elegant experiments, they confirm the occurrence of a decrease in the VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio among African Americans, and showed that a single amino acid substitution near the VWF A1 domain, D1472H, explained the phenomenon.3

By DNA sequencing, the VWF 1472H allele was found in 62% of African Americans and 19% of Caucasians, and it fully accounted for the variation in VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag independent of race. Crucially, the D1472H substitution had no effect on VWF binding to platelet GPIbα in assays that do not use ristocetin, and did not alter VWF binding to collagen. Finally, having one or two 1472H alleles, and the low VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag ratio associated with them, did not correlate with bleeding symptoms.3 Therefore, the VWF D1472H polymorphism causes substantial variation in VWF:RCo without altering the hemostatic function of VWF in vivo.

The effect of the VWF D1472H polymorphism on ristocetin-based assays is not unique (see figure). The VWF mutation P1467S causes a profound decrease in VWF:RCo/VWF:Ag (< 0.1) with no evidence of abnormal hemostasis.4 Conversely, the VWF polymorphism A1381T increases sensitivity to ristocetin and causes artifactually high values of VWF:RCo.5 The VWF variant P1266L, reported independently as VWD type 2B Mälmo and VWD type 1 New York,6,7 also increases sensitivity to ristocetin but, in contrast to typical VWD type 2B, patients with VWF P1266L do not have thrombocytopenia and have a normal VWF multimer distribution; whether VWF P1266L causes bleeding is uncertain.

Examples of dissociation between VWF:RCo and symptoms are analogous to the prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time caused by defects in the contact activation pathway (factor XII, prekallikrein, high-molecular-weight kininogen) that confer no bleeding risk. In each case, knowledge allows us to compensate for the non-ideal performance characteristics of the laboratory test.

The results of Flood et al provide a strong rationale for the development of ristocetin-free VWF assays that should reduce the misdiagnosis of VWD. Meanwhile, in principle, we could replace any thought of race-based reference ranges for VWF:RCo with more precise genome-based criteria, a significant improvement and a small step toward a personalized medicine approach for diagnosing VWD.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.E.S. has consulted for Baxter Innovations and Ablynx and served on advisory boards for Baxter Innovations. ■

REFERENCES

National Institutes of Health

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal