Edification of the human hematopoietic system during development is characterized by the production of waves of hematopoietic cells separated in time, formed in distinct embryonic sites (ie, yolk sac, truncal arteries including the aorta, and placenta). The embryonic liver is a major hematopoietic organ wherein hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) expand, and the future, adult-type, hematopoietic cell hierarchy becomes established. We report herein the identification of a new, transient, and rare cell population in the human embryonic liver, which coexpresses VE-cadherin, an endothelial marker, CD45, a pan-hematopoietic marker, and CD34, a common endothelial and hematopoietic marker. This population displays an outstanding self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation potential, as detected by in vitro and in vivo hematopoietic assays compared with its VE-cadherin negative counterpart. Based on VE-cadherin expression, our data demonstrate the existence of 2 phenotypically and functionally separable populations of multipotent HSCs in the human embryo, the VE-cadherin+ one being more primitive than the VE-cadherin− one, and shed a new light on the hierarchical organization of the embryonic liver HSC compartment.

Introduction

During the third week of human ontogeny, hematopoiesis proceeds first in the yolk sac (YS) and secondarily from the wall of embryonic trunk arteries, the so-called aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region, 1 week later.1 While the YS produces primitive erythrocytes and myeloid progenitors, the first definitive hematopoietic progenitors and hematopoietic stem cells (HP/HSCs) emerge in the AGM region, before their appearance in the embryonic liver (EL).2 In mammalian embryos, EL is a key organ for amplification and differentiation of HSCs. As a matter of fact, EL does not produce its own HSCs de novo, but is thought to be colonized by different waves of HP/HSCs coming from the YS and, later on, from the AGM and the placenta, hence placing the EL at the cross-road of the whole definitive hematopoietic production, before HP/HSCs reach their final location (ie, thymus, spleen, and bone marrow [BM]).3 This onset from various hematopoietic sources, combined with the fact that EL is a site where HP/HSCs are amplified, suggests that this organ could be the first embryonic site where a HSC hierarchy becomes established.

It has been shown that a majority of hematopoietic cells (HCs) including HSCs have an endothelial origin.4,,,,,–10 In this respect, the endothelial-specific VE-cadherin gene (CD144 or cadherin 5), which is essential for endothelial cell-cell interaction11 and required in vivo in the postnatal vasculature to maintain endothelial cell (EC) integrity and barrier function,12 has been instrumental in demonstrating HC production by the endothelium. This question has been documented through in vitro approaches using either primary ECs or mesodermal cells isolated from the embryo13,,–16 or embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation systems.15,,,,–20 In both cases, primitive and definitive hematopoiesis were shown to arise via an endothelial VE-cadherin expressing intermediate. Investigations were also carried out using in vivo transgenic mouse models based on cell tracings using the VE-cadherin regulatory elements (L.P.C., B. El Hafny, E.O., D.C., P. Huber, C. Boucheix, T.J., M.S., manuscript in preparation).6,7 Morover VE-cadherin was also found expressed by HSCs, which appear in the YS and the AGM21,–23 and by a transient HSC population of the mouse fetal liver,24,25 suggesting that this endothelial trait could somehow be associated with an hematopoietic phenotype.

In the present paper, we checked whether such a population bearing a dual hemato-endothelial signature could be detected in the human EL. We show that some HSCs present in the EL coexpress the endothelial-specific marker VE-cadherin, the pan-leukocyte antigen CD45 and the hematoendothelial marker CD34. This VE-cadherin expressing population, which constitutes less than 0.6% of total liver cells, presents higher self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation capacities than the VE-cad−CD34+CD45+ counterpart, as assessed by in vitro hematopoietic assays and long-term transplantation experiments in nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency (NOD/SCID) mice. For the first time, our data provide evidence based on VE-cadherin expression for the existence of 2 phenotypically and functionally separable populations of multipotent HP/HSCs in the human embryo, and shed a new light on the hierarchical organization of the EL HP/HSC compartment.

Methods

Human tissues

Human embryonic and fetal livers (6 to 23 weeks of gestation) were obtained after voluntary, spontaneous or therapeutic, abortions. Informed consent was obtained from the patient in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and tissue collection and use were performed according to the guidelines and with the approval of the French National Ethic Committee. Developmental age was estimated based on several anatomic criteria according to the Carnegie classification for embryonic stages,26 and by ultrasonic measurements for fetal stages. Supplemental Table 1 (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) summarizes the stages of the 77 embryonic and fetal livers used in this study and the type of experiments performed for each stage. All data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Resected human umbilical cords were obtained after normal, full-term deliveries.

Cell preparation

Cell analysis and sorting by flow cytometry

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) used for cell sorting or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses are listed in supplemental Table 2. For cell sorting, cells were incubated for 30 minutes on ice with fluorescein isothiocyanate-anti-CD45, phycoerythrin-anti-VE-cadherin, and allophycocyanin-anti-CD34 antibodies. Labeled cells were washed and selected populations sorted on a FACSDiva cell sorter (BD Biosciences) as previously described.27 Sorted cells were reanalyzed to establish purity.

Cells developed in culture were harvested by nonenzymatic treatment (Cell dissociation solution; Sigma-Aldrich), washed in complete medium, labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to hematopoietic and endothelial markers, and analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

NOD/SCID BM cells were washed, labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies specific to human hematopoietic differentiation, and FACS analyzed. Staining with lineage-specific antibodies was performed concurrently with anti-human CD45 mAb. Specificity of human mAbs was checked on BM cells from nontransplanted mice. Background staining was evaluated using isotype-matched control antibodies. 7-Amino-actinomycine D (7AAD; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to gate dead cells out.

LPP-CFC and HPP-CFC assays

Low-proliferative potential colony-forming cells (LPP-CFCs) and high-proliferative potential colony-forming cells (HPP-CFCs) were assessed in methylcellulose medium using the Methocult GF H4434 kit (StemCell Technologies). After 14 days of culture, colonies were scored and photographed using an Olympus IM inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with a Coolpix 5400 camera (Nikon). Large colonies (diameter > 0.5 mm) were scored as HPP-CFU colonies, while smaller colonies (< 0.5 mm) with at least 50 cells were considered as LPP-CFU colonies.

After counting, colonies were harvested from methylcellulose, dispersed to single-cell suspension, and washed in complete medium. Recovered cells were counted in 0.2% trypan blue. Cell number fold increase between day 0 and day 14 of culture was obtained by calculating the ratio between the quantity of cells obtained at day 14, and the quantity of cells seeded at day 0.

For secondary CFC assays whole primary colonies plucked from methylcellulose on day 14 were replated in 1% methycellulose medium (StemCell Technologies).

Long-term culture on MS-5 stromal cells: assessment of myeloid, NK- and B-cell differentiation potentials

EL sorted cells were cultivated in bulk on MS-5 mouse BM stromal cells29 as previously described,30 except that only 3 human recombinant cytokines were added: 50 ng/mL stem cell factor, 1 ng/mL interleukin-15, 5 ng/mL interleukin-2 (AbCys). Half of the medium was replaced weekly. Colonies of HCs were scored and photographed under an ICM-405 phase-contrast inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss) using an XC-003 3CCD color camera (Sony). Every week, cells collected from wells with significant proliferation were washed, counted in trypan blue, and FACS analyzed after labeling with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to hematopoietic differentiation. The cell number fold increase was obtained by calculating the ratio between the quantity of cells obtained at day 40 and the quantity of cells seeded at day 0.

Frequency of LTC-ICs

The frequency of long-term culture-initiated cells (LTC-ICs) was determined after limiting dilution experiments using Poisson statistics as described previously.27

EC culture

ECs sorted from EL or isolated from umbilical cord veins were grown in endothelial medium as described previously.27 EL double-positive (DP) cells or HCs were cultured in the same conditions except that they were seeded at 2.105 cells/cm2. After 7 days, adherent cells were harvested, labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies to endothelial markers, and FACS analyzed. Image acquisition was done on an ICM-405 phase-contrast inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss) using an XC-003 3CCD color camera (Sony).

NOD/SCID mouse transplantations

NOD/SCID mice (4- to 8-week-old female), sublethally irradiated (3.25 Gy) using a 137Cs source (IBL637; CIS Bio International), received EL 34DP cells or 34HCs by intravenous injection 4 to 24 hours after irradiation. Human HCs engraftment was assessed 4 months after transplantation, by labeling BM cells with fluorochrome-conjugated human-specific antibodies and FACS analysis.

Results

Identification of a VE-cadherin+CD45+ DP population in the human EL

We first looked for cells expressing both endothelial and hematopoietic markers in the human EL. The endothelial VE-cadherin and the pan-hematopoietic CD45 markers were initially used for flow cytometry analysis. Although VE-cadherin and CD45 expression were largely mutually exclusive, a rare population (0.28%) of cells coexpressing these markers could be detected in the 7.7-week-old EL. In addition to this VECAD+CD45+ DP subset, a VECAD+CD45− endothelial subset (EC) and a VECAD−CD45+ hematopoietic subset (HC) were also identified (Figure 1A). Notably the DP population only expressed low levels of VECAD and CD45 (VECADlowCD45low), whereas both EC and HC populations contained cells expressing high or low levels of VE-cadherin (VECADhighCD45− and VECADlowCD45−) and CD45 (VECAD−CD45high and VECAD−CD45low), respectively (Figure 1A).

Hematopoietic markers analysis of HC, EC, and DP fractions in the human EL. (A) Whole liver cells from a 7.7-week-old human EL were double-stained with anti-CD45 and -VE-cadherin mAbs. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating endothelial (VECADhighCD45− [b] and VECADlowCD45− [c]), DP (VECADlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VECAD−CD45high [e] and VECAD-CD45low [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate the percentages of positive cells in the corresponding gates. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Whole liver cells from 7.0- to 8.4-week-old human ELs triple-stained with anti-CD45, anti-VE-cadherin, and anti-hematopoietic-specific mAbs. Relative expression of HC surface antigens by total [a], endothelial (VE-cadherinhighCD45− [b] and VE-cadherinlowCD45− [c]), DP (VE-cadherinlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VE-cadherin−CD45low [e] and VE-cadherin−CD45high [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

Hematopoietic markers analysis of HC, EC, and DP fractions in the human EL. (A) Whole liver cells from a 7.7-week-old human EL were double-stained with anti-CD45 and -VE-cadherin mAbs. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating endothelial (VECADhighCD45− [b] and VECADlowCD45− [c]), DP (VECADlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VECAD−CD45high [e] and VECAD-CD45low [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate the percentages of positive cells in the corresponding gates. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Whole liver cells from 7.0- to 8.4-week-old human ELs triple-stained with anti-CD45, anti-VE-cadherin, and anti-hematopoietic-specific mAbs. Relative expression of HC surface antigens by total [a], endothelial (VE-cadherinhighCD45− [b] and VE-cadherinlowCD45− [c]), DP (VE-cadherinlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VE-cadherin−CD45low [e] and VE-cadherin−CD45high [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.

To determine whether the DP population was present throughout human liver development, 6- to 23-week-old embryonic and fetal livers were analyzed. The DP cell subset was found to decrease during liver development, ranging from 0.63% to 0.03% between 6 and 10 weeks of gestation, and was completely lost in the 23-week-old fetal liver (Table 1 and supplemental Figure 1).

Statistical analysis of VE-cadherin and CD45 expression in 6- to 23-week-old human embryonic and fetal livers

| Developmental stage, weeks of gestation . | No. of embryos per stage . | % VE-cadherin+CD45− cells ± SD (range) . | % VE-cadherin+CD45+ cells ± SD (range) . | % VE-cadherin−CD45+ cells ± SD (range) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 5.22 |

| 6.9 | 1 | 1.39 | 0.57 | 5.47 |

| 7 to 7.4 | 14 | 1.18 ± 0.18 (0.92-1.38) | 0.48 ± 0.069 (0.36-0.54) | 4.51 ± 0.66 (4.04-5.65) |

| 7.5 to 7.9 | 16 | 1.43 ± 0.35 (0.78-1.78) | 0.34 ± 0.06 (0.2-0.44) | 4.67 ± 0.53 (3.99-5.81) |

| 8 to 8.4 | 6 | 1.14 ± 0.23 (0.78-1.44) | 0.12 ± 0.04 (0.06-0.18) | 5.09 ± 0.86 (3.73-6.23) |

| 9 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 3.89 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 3.5 |

| 23 | 1 | 0.24 | 0 | 2.89 |

| Developmental stage, weeks of gestation . | No. of embryos per stage . | % VE-cadherin+CD45− cells ± SD (range) . | % VE-cadherin+CD45+ cells ± SD (range) . | % VE-cadherin−CD45+ cells ± SD (range) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.63 | 5.22 |

| 6.9 | 1 | 1.39 | 0.57 | 5.47 |

| 7 to 7.4 | 14 | 1.18 ± 0.18 (0.92-1.38) | 0.48 ± 0.069 (0.36-0.54) | 4.51 ± 0.66 (4.04-5.65) |

| 7.5 to 7.9 | 16 | 1.43 ± 0.35 (0.78-1.78) | 0.34 ± 0.06 (0.2-0.44) | 4.67 ± 0.53 (3.99-5.81) |

| 8 to 8.4 | 6 | 1.14 ± 0.23 (0.78-1.44) | 0.12 ± 0.04 (0.06-0.18) | 5.09 ± 0.86 (3.73-6.23) |

| 9 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 3.89 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 3.5 |

| 23 | 1 | 0.24 | 0 | 2.89 |

Percent phenotype frequency ± SD (range) for endothelial (VE-cadherin+CD45−), hematopoietic (VE-cadherin−CD45+) and DP (VE-cadherin+CD45+) cell populations are reported as a percentage of total viable cells. SD, standard deviation.

DP cells are highly enriched for HSC markers

An extensive phenotypic characterization of the DP population was next performed and compared with that of EC and HC populations. Analysis of typical endothelial markers such as KDR, CD146, TIE2, and UEA-1 receptor (supplemental Figure 2 and supplemental Table 3) revealed differences between DP and EC populations, since while ECs expressed largely these markers, only few DP cells did (none for CD146). Conversely, a large number of DP cells had a cell surface phenotype that included the expression of CD34, HLA-DR and Thy-1/CD90, and lacked the expression of CD38 (Figure 1B), a phenotype supposed to characterize a compartment of primitive progenitors that may include stem cells in the human fetal liver.31 The HC fraction also contained cells expressing these markers, but to a lesser extent compared with the DP cell fraction (Figure 1B and supplemental Table 3).

CD34, which is both an endothelial and a hematopoietic marker, was detected in all cell fractions. However a clear correlation between the expression of CD34 and VE-cadherin could be observed (Figure 1B). Indeed, while CD34 was expressed on the majority of ECs and DP cells, the number of CD34+ cells dropped significantly in the HC fraction. Of note the majority of CD34+ DP cells (34DP cells) were CD34high (93.8%), while only a fraction of CD34+ HCs (34HCs) was CD34high (46.1%; supplemental Figure 3). Conversely, we checked VE-cadherin expression in the 3 distinct CD34+CD45–, CD34+CD45+, and CD34–CD45+ populations and confirmed that VE-cadherin expression was directly correlated with CD34 expression. The classical CD34+CD45+ HP/HSC population was found to contain both 34DP cells (20.4%) and 34HCs (77%; supplemental Figure 4). Interestingly, DP cells belonged almost exclusively to the CD34high subpopulation, whereas HCs were found both in the CD34high and CD34low subpopulations (supplemental Figure 4).

CD133 (AC133) has been reported to be an alternative marker to CD34 for positive selection of adult hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells.32 However nothing is known about CD133 expression in the EL. We therefore checked its expression and found that CD133 was expressed at a much lower level than CD34 in all cell fractions and that the DP population contained the higher percentage of CD133+ cells (31.4%), while in the HC fraction this percentage decreased dramatically (4.72% and 0% in the VE-cad−CD45low and the VE-cad−CD45high populations, respectively; Figure 1B). CD133 also marked a restricted fraction (27.8%) of the classical CD34+CD45+ HP/HSC population, which was exclusively CD34high (supplemental Figure 5).

Markers associated with early hematopoietic development such as CD49d (α 4-integrin), CD41 and CD43 were also detected in the CD45+ fraction, including DP cells (Figure 1B and supplemental Table 3). However, while CD43 was expressed exclusively in CD45+ cells, including DP and HC cells, CD41 and CD49d were also detected in a small subset of ECs. Conversely to CD49d and CD43, expressed on a large number of cells in both the HC and DP populations, CD41 labeled more cells in the DP than in the HC population (36.3% versus 14%). Interestingly, CD41+ DP cells were exclusively CD41high, whereas CD41+ HCs were either CD41high or CD41low (Figure 1B).

Because HSCs are devoid of lineage-specific antigens, we also checked markers associated with specific lineages, and found that indeed DP cells did not express such markers, except CD33 (early myeloid marker) and to a lesser extend CD14 (monocyte specific marker; supplemental Figure 6).

Altogether our phenotypic study shows that, although expressing VE-cadherin, the DP population contains few cells expressing other endothelial markers and is rather enriched for HSC markers.

The DP population is devoid of endothelial potential

To check whether DP cells could have retained the potential to generate ECs, we sorted them from several EL preparations and tested their in vitro endothelial differentiation capacity. ECs and HCs sorted from the same ELs were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Endothelial formation was found to be restricted to the endothelial population, which adhered shortly after culture initiation, formed a monolayer of adherent cells that became confluent in about 7 days and exhibited the typical endothelial shape, compared with ECs grown from the umbilical vein (HUVECs; supplemental Figure 7A). These cultures uniformly expressed CD31, CD146, and UEA-1 receptor on their surface like HUVECs, as shown by FACS analysis (supplemental Figure 7B). These results strengthen the phenotypical analysis described above and show that although expressing VE-cadherin, the DP population is devoid of endothelial potential.

The 34DP population is endowed with HPP-CFC potential

Since the majority of DP cells expressed CD34 (84.3%; see Figure 1B) we sorted 34DP cells from ELs to evaluate their hematopoietic potential in vitro and in vivo. In all cases, this potential was compared with that of 34HCs sorted from the same ELs. As a positive control we used either the usual CD34+CD45+ (34/45) HP/HSC population, which includes both the 34DP and the 34HC fractions (see above), or total liver cells.

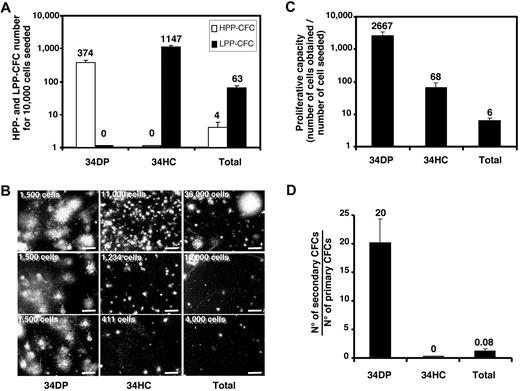

Presence of hematopoietic progenitors in 34DP and 34HC populations was estimated by CFC assays. Total fetal liver suspension was also tested. As illustrated on Figure 2A, all cell populations contained hematopoietic progenitors, but the greatest frequency of CFCs was found in the 34HC population compared with the 34DP or total liver cell populations (1/9, 1/27, and 1/167 CFCs, respectively). However, the 34DP population contained exclusively CFCs with HPP, whereas the 34HC population only contained CFCs with LPP (Figure 2A-B). As expected, total liver cells contained a majority of LPP-CFCs and only few HPP-CFCs (Figure 2A-B). When the proliferative capacity of CFCs contained in each cell population was evaluated by measuring the cell number fold increase between day 0 and day 14 of culture, we observed that the amplification magnitude of 34DP cells was 45-fold higher than for 34HCs (Figure 2C). Moreover, when the self-renewal capacity of hematopoietic progenitors was investigated in secondary CFC assays, only primary colonies derived from 34DP cells were able to generate secondary colonies, with a frequency of 14 secondary CFCs per primary CFC, revealing the high self-renewal ability of progenitors contained within this cell population (Figure 2D). In the same conditions, primary colonies derived from 34HCs and total liver cells were only able to produce a few small colonies, with less than 50 cells (Figure 2D). This indicates that not only progenitors contained in the 34DP fraction present a strikingly greater proliferative capacity, but also have a greater self-renewal ability than those contained in the 34HC fraction.

Proliferative potential of CFCs in 34DP, 34HC, and total EL cell fractions. 34DP, 34HC, and total EL cells were plated in methylcellulose medium. After 14 days of culture, hematopoietic colonies were scored either as HPP-CFC or as LPP-CFC. (A) HPP-CFC and LPP-CFC number normalized to 1.104 cells for each cell population. (B) Typical HPP-CFUs and LPP-CFUs from each cell population (scale bar, 2 mm). The number of cells seeded in methylcellulose is indicated on the left top of each picture. (C) Cell number fold increase for each cell population. (D) Number of secondary CFCs from primary CFCs for each cell population. Each histogram represents the mean value of triplicates with standard deviation in one representative experiment from 3 independent experiments. ELs (7.0-8.4 weeks old) were used for this study.

Proliferative potential of CFCs in 34DP, 34HC, and total EL cell fractions. 34DP, 34HC, and total EL cells were plated in methylcellulose medium. After 14 days of culture, hematopoietic colonies were scored either as HPP-CFC or as LPP-CFC. (A) HPP-CFC and LPP-CFC number normalized to 1.104 cells for each cell population. (B) Typical HPP-CFUs and LPP-CFUs from each cell population (scale bar, 2 mm). The number of cells seeded in methylcellulose is indicated on the left top of each picture. (C) Cell number fold increase for each cell population. (D) Number of secondary CFCs from primary CFCs for each cell population. Each histogram represents the mean value of triplicates with standard deviation in one representative experiment from 3 independent experiments. ELs (7.0-8.4 weeks old) were used for this study.

Extended LTC-ICs are restricted to the 34DP cell fraction

We investigated the long-term hematopoietic potential of 34DP cells by seeding them on MS-5 stroma and compared it to that of 34HCs and 34/45 HP/HSCs. We first determined the time frame of hematopoietic production for each cell population by inspecting cultures every day. Both 34DP cells and 34HCs developed colonies of typical round, stroma-adherent HCs as well as cobblestone-like hematopoietic colonies underneath the stroma (Figure 3A). However, kinetics of hematopoietic production in both cultures were remarkably different. While hematopoietic colonies were observed as soon as 3-4 days in the cultures initiated with 34HCs, they were detected only after 7-8 days with 34DP cells. Conversely, in these latter cultures, colonies could be observed up to day 120, whereas in the cultures initiated with 34HCs, after a quicker initial growth that lasted 3 weeks, a rapid exhaustion was observed with no more colonies detected after 60 days. Of note, although the kinetics of hematopoietic production observed from 34/45 HP/HSCs stood between that of 34DP cells and 34HCs, it rather mimicked that of 34HCs (data not shown). To confirm that 34DP cells were able to generate HCs later than 34HCs and 34/45 HP/HSCs, total progeny produced from each cell population was measured after 40 days of culture. As shown on Figure 3B, the magnitude of amplification for 34DP cells was 50- and 47-fold higher than for 34HCs and 34/45 HP/HSCs, respectively. This indicates that at late culture period 34DP cells were capable to produce much more HCs than 34HCs and 34/45 HP/HSCs.

Long-term hematopoietic potential of 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 EL cell fractions. 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 EL cells were grown on MS-5 stromal cells in bulk (A-B) or in limiting dilution conditions (C-D). (A) Typical colonies of round, stroma-adherent HCs (a,c; Scale bar, 30 μm) and of cobblestone-like colonies underneath the stroma (b,d; Scale bar, 10 μm) obtained after 21 days of culture on MS-5 for 34DP (a,b) and 34HC (c,d) cell populations. (B) Cell number fold increase for 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 cell populations after 40 days of culture on MS-5. Each histogram represents the mean value ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. (C) LTC-IC frequency of both 34HC and 34 DP cell populations at day 28 and 35 of culture on MS-5. (D) LTC-IC frequency of the 34 DP cell populations at day 48, 57, and 70 of culture on MS-5. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

Long-term hematopoietic potential of 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 EL cell fractions. 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 EL cells were grown on MS-5 stromal cells in bulk (A-B) or in limiting dilution conditions (C-D). (A) Typical colonies of round, stroma-adherent HCs (a,c; Scale bar, 30 μm) and of cobblestone-like colonies underneath the stroma (b,d; Scale bar, 10 μm) obtained after 21 days of culture on MS-5 for 34DP (a,b) and 34HC (c,d) cell populations. (B) Cell number fold increase for 34DP, 34HC, and 34/45 cell populations after 40 days of culture on MS-5. Each histogram represents the mean value ± standard deviation of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. (C) LTC-IC frequency of both 34HC and 34 DP cell populations at day 28 and 35 of culture on MS-5. (D) LTC-IC frequency of the 34 DP cell populations at day 48, 57, and 70 of culture on MS-5. Data shown are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

We next evaluated the frequency of LTC-ICs in both 34DP and 34HC populations by performing limiting dilutions analysis on MS-5 cells. 34DP cells were seeded at densities ranging from 1 to 500 cells per well, while 34HCs were seeded at a 50-fold higher density. This analysis confirmed the presence of LTC-ICs within both populations, as observed with bulk cultures. However, dramatic differences in the LTC-IC frequency between both populations were found at different time courses of the culture. LTC-IC frequency of 34HCs culminated at about 1/289 at day 28 of culture, declined at 1/900 at day 35, and thereafter dropped dramatically to become undetectable at day 42 (Figure 3C). In contrast, not only LTC-IC frequency of 34DP cells was higher at day 28 (1/48), but it remained elevated until day 70 (1/288; Figure 3C-D). These results clearly show that the 34DP cell fraction is highly enriched in standard LTC-ICs compared with the 34HC fraction and that it is exclusively endowed with the ability to produce extended LTC-ICs scored beyond the 5 weeks of the standard long-term culture assay.

Delayed but sustained production of myeloid, NK, and lymphoid B cells during long-term culture of 34DP cells

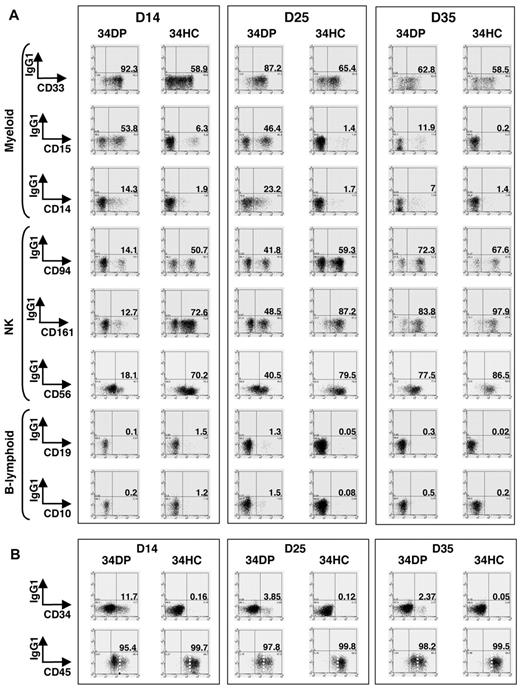

We next evaluated precisely the kinetics of hematopoietic differentiation of 34DP cells and compared it to that of 34HCs and 34/45 HP/HSCs. Bulk cultures on MS-5 stroma were performed, and after 14, 25, and 35 days, whole cultures were harvested and stained with CD34, CD45, VE-cadherin, and lineage-specific antibodies. Flow cytometric analysis indicated that for both 34DP and 34HC populations, all the cells produced expressed the pan-leukocytic marker CD45 and had differentiated into myeloid (CD33+, CD15+, CD14+), NK (CD94+, CD56+, CD161+), and B-lymphoid (CD19+, CD10+) lineages (Figure 4A). However, loss of CD34+ progenitors and production of CD45high cells were extremely different in both cultures. Indeed, after 2 weeks of culture, only wells seeded with 34DP cells still contained substantial number of CD34+ cells (11.7%), which then decreased but could be maintained over long-term in the culture, whereas wells seeded with 34HCs contained only 0.16% of CD34+ cells that disappeared after 5 weeks (Figure 4B). In addition, while CD45low cells could still be observed after 5 weeks in cultures initiated with 34DP cells, 34HCs rapidly differentiated in CD45high cells, and only few CD45low cells were detected after 5 weeks (Figure 4B). Strikingly, reanalysis of VE-cadherin at different time points of both cultures showed that VE-cadherin was rapidly lost in the DP fraction upon culture (Figure 5). Yet, this loss of VE-cadherin was not associated to a failure of the hematopoietic potential of DP cells.

Kinetics of CD34+ HPs, CD45high mature HCs, myeloid, NK, and B-lymphoid cells in long-term culture of human EL 34DP cells compared with 34HCs. 34DP and 34HC EL cells were grown on MS-5 stromal cells. After 14, 25, and 35 days, the whole content of cultures was harvested and stained with antibodies to human lineage-specific markers (A) and human CD34, CD45 (B). (A) Lineage-specific stainings of HCs obtained after 14, 25, and 35 days of culture on MS-5. 34DP cells and 34HCs produce CD33+, CD15+, CD14+ myeloid, CD94+, CD161+, CD56+ NK, and CD19+, CD10+ B-lymphoid cells. 34DP cells produce the same progeny as 34HCs but with delayed and prolonged kinetics. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D, day. (B) CD34 and CD45 stainings of HCs obtained after 14, 25, and 35 days of culture on MS-5. The loss of CD34+ progenitors and the production of CD45high cells are delayed in cultures initiated with 34DP cells compared with cultures initiated with 34HCs. Markers are shown on the x-axis. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells for each marker. Dotted lines discriminate between CD45low and CD45high cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

Kinetics of CD34+ HPs, CD45high mature HCs, myeloid, NK, and B-lymphoid cells in long-term culture of human EL 34DP cells compared with 34HCs. 34DP and 34HC EL cells were grown on MS-5 stromal cells. After 14, 25, and 35 days, the whole content of cultures was harvested and stained with antibodies to human lineage-specific markers (A) and human CD34, CD45 (B). (A) Lineage-specific stainings of HCs obtained after 14, 25, and 35 days of culture on MS-5. 34DP cells and 34HCs produce CD33+, CD15+, CD14+ myeloid, CD94+, CD161+, CD56+ NK, and CD19+, CD10+ B-lymphoid cells. 34DP cells produce the same progeny as 34HCs but with delayed and prolonged kinetics. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D, day. (B) CD34 and CD45 stainings of HCs obtained after 14, 25, and 35 days of culture on MS-5. The loss of CD34+ progenitors and the production of CD45high cells are delayed in cultures initiated with 34DP cells compared with cultures initiated with 34HCs. Markers are shown on the x-axis. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells for each marker. Dotted lines discriminate between CD45low and CD45high cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

Rapid loss of VE-cadherin in EL DP cells after in vitro culture on MS-5 stroma. Flow cytometric analysis of total liver cells triple stained with anti-CD45-fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-CD34-allophycocyanin, and anti-VE-cadherin-phycoerythrin mAbs shows that as soon as 24 hours of culture on MS-5 stroma, almost no VE-cadherin+ cells are detected anymore in the DP VECAD+CD45+ cell fraction. The black gate delimitates the DP VECAD+CD45+ cell fraction. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

Rapid loss of VE-cadherin in EL DP cells after in vitro culture on MS-5 stroma. Flow cytometric analysis of total liver cells triple stained with anti-CD45-fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-CD34-allophycocyanin, and anti-VE-cadherin-phycoerythrin mAbs shows that as soon as 24 hours of culture on MS-5 stroma, almost no VE-cadherin+ cells are detected anymore in the DP VECAD+CD45+ cell fraction. The black gate delimitates the DP VECAD+CD45+ cell fraction. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells. D indicates day.

The kinetics of lineage differentiation was also extremely different in both cultures. Although cells from both populations underwent a series of differentiation steps leading first to the generation of myeloid cells and later on of B-lymphoid and NK cells, all the cultures seeded with 34DP cells presented a delayed but prolonged production of all lineages compared with cultures initiated with 34HCs (Figure 4A). Indeed, after 2 weeks of culture, more myeloid cells were present in the culture initiated with 34DP cells than with 34HCs (34HCs already produced them at earlier time points of the culture). Later on, 34DP cells also generated B-lymphoid and NK cells, again with a delay compared with 34HCs (Figure 4A). Interestingly, 34DP cells were still producing myeloid, NK, and some CD34+ cells after 63 days of culture, while no hematopoietic production was observed anymore with 34HCs (data not shown). As for the kinetics of hematopoietic production, the kinetics of hematopoietic differentiation in cultures initiated with 34/45 HP/HSCs were either the same as 34HCs or in between that of 34DP cells and 34HCs.

Altogether, long-term culture assays clearly showed that 34DP cells are able to maintain CD34+ progenitors for a longer period of time than 34HCs and to yield all blood cell progenies with a delayed but prolonged kinetics of hematopoietic differentiation compared with 34HCs.

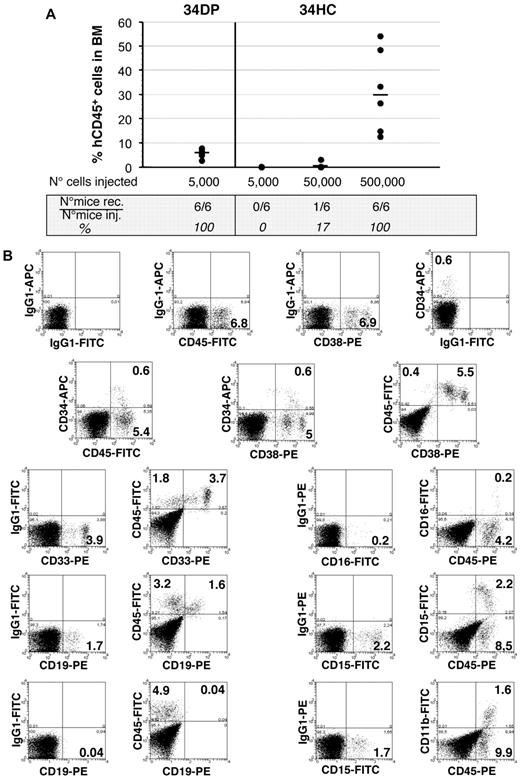

The 34DP cell population is enriched in SCID repopulating cells

34DP cells and 34HCs were next transplanted into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice to test their repopulating ability. Six of 6 mice transplanted with as few as 5000 34DP cells exhibited good levels of engraftment 4 months after transplantation, whereas no engraftment was observed in mice transplanted with 5000 34HCs (Table 2 and Figure 6). For this latter population, engraftment could be observed only when 10 times more cells were injected, with 1 mouse of 6, and 6 mice of 6 being reconstituted for 50 000 and 500 000 cells injected, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 6). In addition, mice reconstituted with 34DP cells demonstrated multilineage engraftment as assessed by BM cells staining with antibodies to myeloid (CD33, CD15, CD11b, and CD16) and B-lymphoid (CD19) lineages (Figure 6). Interestingly the proportion of human B-lymphoid and myeloid cells obtained in those mice was significantly different to that observed in mice reconstituted with 34HCs. Indeed, with 34DP cells the human myeloid compartment was approximately 3.5-fold greater than the human B-lymphoid compartment, whereas with 34HCs the number of human myeloid cells was dramatically reduced, with the typical proportional predominance of human B-lymphoid cells (between 3- and 5-fold when 50 000 or 500 000 cells were injected; supplemental Figure 8). In addition, a significant fraction of both primitive CD34+CD38low and mature CD34+CD38+ human progenitors were still found in the BM of mice injected with 34DP cells (Figure 6), while a very low percentage of these respective progenitors could be detected in the BM of mice transplanted with 34HCs, even when 500 000 cells were injected (data not shown). Altogether these results demonstrate that the majority of SCID repopulating cells are contained within the 34DP cell fraction.

Hematopoietic reconstitution capacity of human EL 34DP cells and 34HCs in primary NOD/SCID mice

| Age, weeks of gestation . | Sorted cells . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total mice . | |||

| 8.4 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 0/2 | ||

| 7.8 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 0/2 | ||

| 7 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 1/2 |

| Age, weeks of gestation . | Sorted cells . | No. of injected cells . | Engrafted mice* . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total mice . | |||

| 8.4 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 0/2 | ||

| 7.8 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 0/2 | ||

| 7 | 34DP | 5000 | 2/2 |

| 34HC | 5000 | 0/2 | |

| 50 000 | 1/2 |

Engraftment is based on flow cytometric analysis of BM cells from recipient mice harvested at 4 months after transplantation and is defined as more than 1% human CD45+ cells.

Long-term hematopoietic reconstitution of NOD/SCID mice by EL 34DP cells and 34 HCs. (A) Samples of 5000 34DP cells, and 5000, 50 000, and 500 000 34HCs sorted from 7.0- to 8.4-week-old human EL cells were injected into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice, and mice were tested for the presence of human CD45+ cells in their BM 4 months after transplantation. Each dot represents the level of reconstitution of individual mouse. Median of reconstitution is reported (black lines). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of NOD/SCID recipient mouse BM 4 months after transplantation of 5000 34DP cells sorted from a 7-week-old human EL. 34DP cells demonstrated multilineage engraftment with an atypical proportion of B-lymphoid and myeloid cells as assessed by triple-staining with human specific mAbs to CD45, CD34, and CD38 and double-staining with human specific mAbs to CD45 and either myeloid (CD33, CD15, CD11b, CD16), B-lymphoid (CD19), or NK (CD94) cells. In addition, a significant fraction of primitive CD34+CD38low and mature CD34+CD38+ human progenitors were still found in the BM of the injected mouse. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells.

Long-term hematopoietic reconstitution of NOD/SCID mice by EL 34DP cells and 34 HCs. (A) Samples of 5000 34DP cells, and 5000, 50 000, and 500 000 34HCs sorted from 7.0- to 8.4-week-old human EL cells were injected into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice, and mice were tested for the presence of human CD45+ cells in their BM 4 months after transplantation. Each dot represents the level of reconstitution of individual mouse. Median of reconstitution is reported (black lines). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of NOD/SCID recipient mouse BM 4 months after transplantation of 5000 34DP cells sorted from a 7-week-old human EL. 34DP cells demonstrated multilineage engraftment with an atypical proportion of B-lymphoid and myeloid cells as assessed by triple-staining with human specific mAbs to CD45, CD34, and CD38 and double-staining with human specific mAbs to CD45 and either myeloid (CD33, CD15, CD11b, CD16), B-lymphoid (CD19), or NK (CD94) cells. In addition, a significant fraction of primitive CD34+CD38low and mature CD34+CD38+ human progenitors were still found in the BM of the injected mouse. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments performed on 7.0- to 8.4-week-old EL cells.

HP/HSC hierarchy defined by VE-cadherin in the human EL. (A) During human embryonic development, different waves of VE-cadherin+CD34+CD45− hemogenic ECs are produced in the YS, AGM, and potentially in the placenta (Pl). These hemogenic ECs give rise to VE-cadherin+CD34+CD45+ 34DP cells that migrate to the EL. Very quickly after EL colonization, VE-cadherin is lost in the progeny of 34DP cells. This progeny (34HCP) is composed of VE-cadherin−CD34+CD45+ cells that display in vitro high proliferation, self-renewal and extended LTC-IC capacity, as well as LT-SRC ability in vivo, and could represent 34pre-HC cells. Eventually, 34HCP cells will end up giving rise to the classical VE-cadherin−CD34+CD45+ 34HCs, endowed with in vitro low proliferating, self-renewal, and standard LTC-IC capacity, as well as ST-SRC ability in vivo. (B) Schematic representation of the transitions of the various HCs populations in the human EL during development. LT-SRC, long-term SCID repopulating cells; ST-SRC, short-term SCID repopulating cells.

HP/HSC hierarchy defined by VE-cadherin in the human EL. (A) During human embryonic development, different waves of VE-cadherin+CD34+CD45− hemogenic ECs are produced in the YS, AGM, and potentially in the placenta (Pl). These hemogenic ECs give rise to VE-cadherin+CD34+CD45+ 34DP cells that migrate to the EL. Very quickly after EL colonization, VE-cadherin is lost in the progeny of 34DP cells. This progeny (34HCP) is composed of VE-cadherin−CD34+CD45+ cells that display in vitro high proliferation, self-renewal and extended LTC-IC capacity, as well as LT-SRC ability in vivo, and could represent 34pre-HC cells. Eventually, 34HCP cells will end up giving rise to the classical VE-cadherin−CD34+CD45+ 34HCs, endowed with in vitro low proliferating, self-renewal, and standard LTC-IC capacity, as well as ST-SRC ability in vivo. (B) Schematic representation of the transitions of the various HCs populations in the human EL during development. LT-SRC, long-term SCID repopulating cells; ST-SRC, short-term SCID repopulating cells.

Discussion

In the present paper, we identified a new, rare cell subpopulation in human EL, which coexpresses the endothelial specific marker VE-cadherin and the pan-leukocyte antigen CD45. Despite VE-cadherin expression, this DP population is unable to give rise to ECs. On the contrary, this population exhibits striking HSC features and is endowed with a high proliferative and self-renewal hematopoietic potential.

The human EL DP population presents higher similarities with HCs than with ECs and is highly enriched in HSC markers

Extensive flow cytometric characterization of this rare DP cell subset showed that unlike ECs sorted from the same ELs, only few DP cells expressed endothelial markers such as KDR, TIE2, and UEA-1 receptor. Conversely, a large number of DP cells expressed classical HSC cell-surface markers such as CD34, AC133/CD133, Thy-1/CD90, and HLA-DR, and lacked CD38 expression. In agreement with this HSC phenotype, DP cells did not express classical cell-surface markers associated with hematopoietic lineage differentiation except the early myeloid lineage marker CD33. This is in keeping with studies that described myeloid marker expression on human adult and fetal HSCs.31,33

In addition, DP cells displayed markers associated with the first developmental steps of hematopoietic differentiation such as CD49d, expressed by the earliest hematopoietic progenitors that have diverged from the endothelial lineage,34,35 CD41, which marks the first definitive HCs emerging in the embryo36,,,–40 and CD43, which discriminates between ECs and HCs during human ES cell differentiation.41

Thus, the DP population presents a unique combinatory expression of markers, displaying cell surface molecules associated with fetal and adult HSCs together with hallmarks of the early HCs found during the first steps of hematopoietic system development. A similar DP population has also been described in the mouse fetal liver.24,25 However, unlike murine fetal liver DP cells, most human EL DP cells have lost the expression of endothelial-specific genes. Despite this difference, in both species DP cells were unable to grow in endothelial culture conditions, whereas the VE-cadherin+CD45− EC population did. In addition, the mouse DP population was also described to be entirely positive for the early myeloid lineage marker MAC1,25 which is also an early embryonic HSC marker.42,43 It was suggested that MAC1 could mark a diverging point between the segregating endothelial and hematopoietic compartments.25 CD33, expressed on the majority (82%) of human EL DP cells, might identify a similar stage in the human EL.

VE-cadherin expression allows establishing a functional hierarchy within the EL CD34+CD45+ HP/HSC population

In vitro and in vivo hematopoietic assays revealed dramatic differences between 34DP cells and 34HCs. First, CFC assays showed that although 34DP cells gave rise to a much lower frequency of hematopoietic colonies than 34HCs, all the 34DP-derived colonies presented the typical HPP-CFUs macroscopic characteristics, while 34HCs did not produce this type of colonies. In addition, only 34DP cells produced secondary hematopoietic colonies, meaning that the DP fraction contained all the progenitors with high proliferative and self-renewal capacity. Second, 34DP cells kinetics of proliferation in long-term culture assays was distinct from that of 34HCs; 34DP cells produced HCs with a delay compared with 34HCs and extended long-term hematopoiesis (observed after more than 60 days of culture) only occurred with this population. In addition, although both long-term cultures of 34DP cells and 34HCs first lead to the generation of myeloid cells and later on of B-lymphoid and NK cells, all the differentiation steps of 34DP cells were strikingly delayed. Third, the repopulating ability of 34DP cells in NOD/SCID mice was much higher than that of 34HCs. While all transplanted mice were reconstituted with as few as 5000 34DP cells, only 1 mouse of 6 was reconstituted with 50 000 34HCs. In addition, 34DP cells produced a human lymphomyeloid progeny with a proportional predominance of myeloid cells, while 34HCs predominantly generated the expected B cell progenitors in this context. This indicates that in vivo 34DP cells might also differentiate with a slower kinetic compared with 34HCs, producing predominantly myeloid cells first and lymphoid cells only thereafter. This early appearance of myeloid commitment followed by the late detection of the lymphoid lineage is also found during evolution,44 and notably during embryonic development.2,45 The delay in 34DP cells differentiation observed in vitro and in vivo most likely reflects the delayed recruitment of more primitive progenitors and/or stem cells contained within this fraction compared with 34HCs. This last hypothesis is in accordance with recent data reported by Dykstra et al, who identified 2 categories of HSCs with long-term reconstitution potential, an α-type that produces a substantially higher proportion of myeloid cells compared with lymphoid progeny and a β-type presenting a more balanced distribution of lineage output. Interestingly, approximately half of the HSCs that generated an α-cell repopulation pattern in primary recipients switched to a β-cell repopulation pattern when serially transplanted, while the reverse was not observed.46

Are 34DP cells and 34HCs hierarchically related?

During human EL development, the DP population decreased dramatically and disappeared completely at the fetal liver stage. This is reminiscent of what has been described for mouse fetal liver,24,25 where a similar switch from VE-cadherin+CD45+ DP cells to VE-cadherin−CD45+ HCs, linked to the developmental time, was also reported.25 Thus DP cells could represent a transient HSC population, suggesting that as hematopoietic development progresses in the liver, VE-cadherin is down-regulated and that VE-cadherin+ DP cells could give rise to VE-cadherin− HCs.

Interestingly, we could reproduce in vitro the VE-cadherin down-regulation observed in vivo, which strengthens the fact that in the EL, the 34DP cells could very rapidly give rise to a 34HC progeny (34HCP). Yet, this in vitro loss of VE-cadherin expression in 34DP cells was not associated to a loss of the exceptional hematopoietic potential of the DP cells, suggesting that this DP cell-specific potential persisted even after the disappearance of the hallmark associated to these primitive traits. We propose that 34DP and 34HCP cells could represent a “pre-34HC” population characterized by an extended CD34 expression in culture and endowed with higher proliferation, self-renewal, and repopulation potentials compared with the 34HC population (Figure 7).

Does the 34DP population originate from hemogenic endothelium?

It is now admitted that the first embryonic HCs originate from hemogenic ECs. Various transgenic mouse models based on VE-cadherin demonstrated the direct filiations from ECs to HCs6,7 (L.P.C., B. El Hafny, E.O., D.C., P. Huber, C. Boucheix, T.J., M.S., manuscript in preparation) and reinforced observations based on ES cell differentiation, which demonstrated an hematopoietic production from VE-cadherin expressing cells.17,–19 As for the mouse, given VE-cadherin expression, the DP fraction could represent an intermediate population between the hemogenic ECs that we previously identified in the human embryo27 and the more advanced HC population that lacks VE-cadherin expression. Indeed, the set of early hematopoietic genes expressed at the surface of DP cells stand at the diverging point between ECs and HCs.34,35,40,41 Hence, the DP population could diverge from hemogenic ECs before the onset of definitive hematopoiesis, loosing endothelial markers as they gain expression of hematopoietic markers.

Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo observations suggest that EL CD34+CD45+ HP/HSCs fall into 2 subpopulations that exhibit distinct self-renewal, proliferation, and differentiation potential, the VE-cadherin+ one being more primitive than the VE-cadherin− one. VE-cadherin+ 34DP cells could represent an earlier stage of hematopoietic development than VE-cadherin− 34HCs. Whether these 2 subsets of cells could also represent 2 different populations of cells migrating independently in the EL, with 34DP cells ending up producing classical 34HCs, remains to be elucidated.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr Françoise Dieterlen for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank the SEIVIL animal core facility for NOD/SCID breeding and nursing.

This work was supported by Inserm, the Institut de Cancérologie et d'Immuno-Génétique (ICIG) and by grants from ARC/Inca and the Groupement des Entreprises Françaises dans la Lutte contre le Cancer (GEFLUC). M.F. was supported by the Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie (MENRT), the Association ANRB Vaincre le Cancer, and the Société Française d'Hématologie (SFH).

Authorship

Contribution: E.O. designed and performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; M.F. performed some FACS experiments and contributed to figure preparation; D.C. performed cell sorting; L.P.C. contributed to technical assistance for in vivo experiments; J.J.C. and B.M. provided human embryonic and fetal tissues; T.J. contributed to manuscript writing; and M.S. contributed to discussion of experimental design and results and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for L.P.-C. and M.S. is CNRS, UMR7622, Paris, France.

Correspondence: Estelle Oberlin, Inserm U935, Bâtiment Lavoisier, Hôpital Paul Brousse, 12, avenue Paul Vaillant-Couturier, 94807 Villejuif cedex, France; e-mail: estelle.oberlin@inserm.fr; or Michèle Souyri, CNRS UMR7622 “Biologie du développement,” UPMC, 9 quai Saint Bernard, Bâtiment C-6ème étage-case 24, 75252 Paris Cedex 05, France; e-mail: michele.souyri@snv.jussieu.fr.

![Figure 1. Hematopoietic markers analysis of HC, EC, and DP fractions in the human EL. (A) Whole liver cells from a 7.7-week-old human EL were double-stained with anti-CD45 and -VE-cadherin mAbs. Flow cytometric analysis demonstrating endothelial (VECADhighCD45− [b] and VECADlowCD45− [c]), DP (VECADlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VECAD−CD45high [e] and VECAD-CD45low [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate the percentages of positive cells in the corresponding gates. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (B) Whole liver cells from 7.0- to 8.4-week-old human ELs triple-stained with anti-CD45, anti-VE-cadherin, and anti-hematopoietic-specific mAbs. Relative expression of HC surface antigens by total [a], endothelial (VE-cadherinhighCD45− [b] and VE-cadherinlowCD45− [c]), DP (VE-cadherinlowCD45low [d]), and hematopoietic (VE-cadherin−CD45low [e] and VE-cadherin−CD45high [f]) cell populations. Numbers indicate percentages of positive cells in the corresponding quadrants. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/116/22/10.1182_blood-2010-03-272625/6/m_zh89991060150001.jpeg?Expires=1767900365&Signature=AKaRHL0F0~H9fypwkwPtpJDOXo6wH7lx5ZaASXaq2IIDVrHKDPsQEphKxCk24MDR7-qBCTnpQxNkfaXd1mWFdTp3WOI0g6ldyHZYUe0KpfupTpPWAytaZhYj-ZVhYeIcRngAzBsroKaCvx1rE2J-ntM47VlthacbR1hjY3vvZUg3YNb4oBAvC2RAtRAVt18o0Bs9GKzhEmQj9TkUSCGSE-UqyaWlopvpIyvnrP2x3i4UtpZkfpMOg0lEeXElBK4bNu4UUWt8oHnosZ4hE4TRWqAekQuv6gyICrOSlfga3HuECe42IeMgXqlbaWAWnohFn4nj5OfecwIrhq7bAHF-~Q__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal