Abstract

Our previous work has shown that axon guidance gene family Nogo-B and its receptor (NgBR) are essential for chemotaxis and morphogenesis of endothelial cells in vitro. To investigate NogoB-NgBR function in vivo, we cloned the zebrafish ortholog of both genes and studied loss of function in vivo using morpholino antisense technology. Zebrafish ortholog of Nogo-B is expressed in somite while expression of zebrafish NgBR is localized in intersomitic vessel (ISV) and axial dorsal aorta during embryonic development. NgBR or Nogo-B knockdown embryos show defects in ISV sprouting in the zebrafish trunk. Mechanistically, we found that NgBR knockdown not only abolished its ligand Nogo-B–stimulated endothelial cell migration but also reduced the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and vascular endothelial growth factor–induced chemotaxis and morphogenesis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Further, constitutively activated Akt (myristoylated [myr]Akt) or human NgBR can rescue the NgBR knockdown umbilical vein endothelial cell migration defects in vitro or NgBR morpholino-caused ISV defects in vivo. These data place Akt at the downstream of NgBR in both Nogo-B– and VEGF-coordinated sprouting of ISVs. In summary, this study identifies the in vivo functional role for Nogo-B and its receptor (NgBR) in angiogenesis in zebrafish.

Introduction

Blood vessel and peripheral nerve formation are intricately associated processes that are important for both physiological and pathological conditions, and this subject is under active investigation.1 Several cell surface molecules, such as neuropilin,2 ephrin-B2,3 plexin,4 and Robo4,5,6 have been shown to be involved in both angiogenesis and neurogenesis. Recently, Nogo isoforms-A, -B, and -C, members of the reticulon family of proteins, have joined this list. Nogo-A and Nogo-C are highly expressed in central nervous system. Nogo-C is uniquely expressed in skeletal muscle, while Nogo-B is found in most tissues.7,8 Nogo-A is well characterized as a negative regulator of axon sprouting.9,10 However, less attention has been paid to the function or significance of other Nogo isoforms in non-neural tissues. Using proteomics-based discovery approaches, Nogo-B was previously identified as a protein that is highly expressed in caveolin-1 enriched microdomains and/or lipid rafts of endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells.11 Mice deficient in Nogo-A/B show exaggerated neointimal proliferation, abnormal remodeling,11 and a deficit in ischemia-induced arteriogenesis and angiogenesis.12 Previously, we have demonstrated that the amino terminus (residues 1-200) of Nogo-B (AmNogo-B) promotes the adhesion of endothelial and smooth muscle cells and serves as a chemoattractant for endothelial cells while antagonizing platelet-derived growth factor–induced vascular smooth muscle cell migration.11 An expression cloning approach identified a receptor specific for AmNogo-B, called NgBR.13 High-affinity binding of AmNogo-B to NgBR is sufficient for AmNogo-B–mediated chemotaxis and tube formation of endothelial cells.13 To date, no in vivo function has been identified for NgBR. Here we use the zebrafish model system to investigate NgBR and Nogo-B function in vivo and demonstrate that NogoB-NgBR ligand-receptor pair is necessary for intersomitic vessel (ISV) formation. Genetic knockdown of Nogo-B or NgBR by antisense morpholinos (MOs) resulted in ISV defects during embryonic angiogenesis. Further, ISV defects caused by NgBR or Nogo-B loss of function can be rescued using constitutively activatedmyrAkt, suggesting that NogoB-NgBR signaling results in downstream Akt activation, which triggers angiogenesis in vivo.

Methods

Antibodies and reagents

NgBR rabbit polyclonal antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits (Imgenex) using the peptide CRNRRHHRHPRG (residues from 64-74 of human NgBR). The antiserum was purified using peptide-conjugated SulfoLink Coupling Gel (Pierce). Antibodies for phos-Akt (S473), phos-p42/44 extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), phos- vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)2 (Y1175), total Akt, and ERK were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. We also used antibodies to VEGFR2 (Cell Signaling Technology), heat-shock protein-90 (BD Biosciences), and hemagglutinin (Roche).

Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, passage 2-6) were grown in Medium 199 (Invitrogen) containing penicillin (100 U/mL), streptomycin (100 mg/mL), 20% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (HyClone), and endothelial cell growth supplement (BD Biosciences). Recombinant human VEGF-165 is a gift from Genentech.

Transfection of siRNA and plasmid DNA to HUVECs

The sequences of NgBR siRNA and nonsilencing (NS) siRNA (control siRNA) were described in our previous publication13 and were synthesized by QIAGEN. Transfection of NgBR siRNA was performed as previously described.13 To rescue the migration defect caused by NgBR siRNA, HUVECs were transfected with plasmid DNA of NgBR coding region or myrAkt (myristoylated human Akt) and kinase-dead mutant of human Akt (myrAkt-KD; kind gifts from Dr Joanne Chan at Vascular Biology Program, Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School), by electroporation using the MicroPorator (Neon Transfection System from Invitrogen) at 8 hours before siRNA treatment. Migration assay and examination of cell signaling were performed at 65 hours after transfection, and tube formation was performed at 48 hours after transfection.

Zebrafish stocks

Zebrafish were grown and maintained at 28.5°C.14 All procedures were performed according to Medical College of Wisconsin animal protocol guidelines (ASP No. 312-06-2). Mating was routinely carried out at 28.5°C, and embryos were staged according to established protocols.15 Wild-type (WT) fish used in this study include TL, AB, TuAB strains.

MO design

Based on the sequences of zebrafish ortholog of NgBR (zgc:92 136/NM_001002356) and Nogo-B (zgc:92 163/NM_001079912), ATG MO and splice MO phosphorodiamidate oligonucleotides were designed by Gene Tools. The sequences of zNgBR MOs are as follows: MO1 (ATG-MO) sequence is ACACCATCTCATACAGCGAAGCCAT; MO2 (splice MO), ATTCAGGTTTTGAGTCTCACCTTGA; MO3 (splice MO), ACCAACACACAGTGCCTCACCTTTG. The sequences of zNogo-B MOs are as follows: MO1 (ATG-MO) sequence is TCATCCATTGTTGCGAATGTGTCGA, and MO2 (splice MO) sequence is ACATTAAATTACTTACATGAGCACG. Control MO, CCTCTTACCTCAGTTAC AATTTATA, was purchased from Gene Tools.

MO/RNA injections

Microinjections of one-cell stage zebrafish embryo with RNA or MO were carried out as previously described.14 MOs were reconstituted in nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of 2mM (16 ng/nL). Appropriate dilutions were made in 5× injection dye (100mM HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid]/1M KCl/1% phenol red), and ≈2-3 nL of MOs (8-12 ng) were injected at the one-cell stage. For rescue experiments, 50-100 pg capped RNA of hNgBR (human NgBR), hNogo-B (human Nogo-B), hAmNogo-B (amino-terminus of human Nogo-B), myrAkt, or myrAkt-KD was injected with 6-9 ng of either zNgBR MO3 or zNogo-B MO2.

In situ hybridization and immunostaining

Embryos were grown in 0.003% phenylthiourea until the desired stage, dechorionated first and then fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C, and stored in 100% methanol at −20°C until use. Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was carried out as described in previous publication.16 Antisense probes were generated with T7 RNA polymerase using NotI linearized vector containing 1.2 kb of zNgBR fragment and 0.7 kb of zNogo-B fragment, respectively. Hybridized embryos were photographed using a Leica MZ16FA stereomicroscope equipped with a QImaging camera and Image Pro AMS 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics) as previously described.17 All images were taken with embryos mounted in glycerol as described before17 and images assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS. Images were enhanced by auto color correction and auto contrast feature in Adobe Photoshop CS. Serial transverse and sagittal NgBR sections were generated as described before17 from Spurr epoxy resin embedded 22-24 hours postfertilization (hpf) embryos. Probes for fli1a, etsrp, myod, and flk1 have been described before.17-20

Alkaline phosphatase fusion protein binding

Assays for alkaline phosphatase (AP)–VEGF binding were done as previously described.13 Cells were incubated with 10nM AP- or AP-VEGF–conditioned medium in binding buffer (medium 199 containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin) at 4°C for 2 hours. Unbound proteins were removed, and bound proteins were solubilized in 1% Triton X-100. After vortexing vigorously, the nuclei were spun out, and supernatants were heated for 10 minutes at 65°C. AP activity was determined by measuring optical density at 410 nm as previously described.13 The bound AP or AP-VEGF on the surface of fixed HUVECs was also detected using the Blue Substrate kit (Vector Laboratories) as previously described.13

Western blot analysis

Total cell lysates were prepared by adding 200 μL of cell lysate buffer containing 20mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), 1mM EGTA (ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid), 2.5mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1mM Na3VO4, 1mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1% Triton X-100, and 1 μg/mL leupeptin. Total cell extract (50 μg) was separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). Phosphorylation of p42/44 ERK and Akt kinase (S473) and total levels of p42/44 ERK and Akt were determined using a rabbit polyclonal phospho-specific p42/44 ERK and Akt antibody (Cell Signaling) and rabbit polyclonal p42/44 ERK and Akt antibody (Cell Signaling) as previously described.21

Migration experiments

A modified Boyden chamber was used (Costar transwell inserts; Corning, Inc.). The transwell inserts were coated with a solution of 0.1% gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline at 4°C overnight and then air-dried. VEGF at 100 ng/mL (2.2nM) dissolved in medium 199 containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin was added in the bottom chamber of Boyden apparatus. HUVECs (1 × 105 cells) suspended in a 100-μL aliquot of medium 199 containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin were added to the upper chamber. After 4-5 hours incubation, cells on both sides of the membrane were fixed and stained with Diff-Quik staining kit (Baxter Healthcare Corp, Dade Division). The average number of cells from 5 randomly chosen high-power (200×) fields on the lower side of the membrane was counted.

Collagen gel tube formation assay

HUVECs were resuspended (final concentration 1 × 106) in a mixture of 1 mL containing rat tail type I collagen (1.5 mg/mL, BD Biosciences), 1/10 volume 10× M199, and 1M HEPES and neutralized with NaOH. Droplets (0.2 mL each) of the cell/collagen mixture were placed in nontissue culture–treated dishes and allowed to polymerize for 15 minutes at 37°C. M199 medium containing either vehicle or recombinant human VEGF (100 ng/mL) as well as 1% FBS was then added to each well. HUVECs were allowed to form tube-like structures for 1-2 days. To evaluate tube formation in 3-dimensional (3D) cultures, cells were photographed using Leica DMIL imaging system with QCapture Program (QImaging Inc), and total-network length (defined as an elongation of cell into tubelike structures typically seen in 3D cultures) was quantified in 5 fields for each triplicate per experiment using the measurement tools provided with National Institutes of Health ImageJ 1.40g.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, and the statistical significance of differences was evaluated with the ANOVA analysis. Significance was accepted at the level of P < .05.

Results

Cloning and characterization of NgBR and Nogo-B in zebrafish

We identified the ortholog of NgBR in zebrafish (NM_001002356, Danio rerio zgc:92 136) based on published genomic data in PubMed. The alignment of zebrafish NgBR (zNgBR) with human NgBR (hNgBR) and mouse NgBR (mNgBR) shows that zNgBR has approximately 80% homology with both hNgBR and mNgBR (supplemental Figure 1A, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). Zebrafish NgBR has conserved transmembrane domain and 90% homology of cytoplasmic domain compared with mNgBR and hNgBR.

We also identified the ortholog of Nogo-B (NM_001079912, Danio rerio zgc:92 163), the known ligand for NgBR. The alignment of zebrafish Nogo-B (zNogo-B) with human Nogo-B (hNogo-B) and mouse Nogo-B (mNogo-B) shows that zNogo-B has approximately 60%-70% homology with both hNogo-B and mNogo-B (supplemental Figure 1B). Zebrafish Nogo-B has conserved active domain (181-200 aa at the N-terminal domain), transmembrane domain, and cytoplasmic domain compared with mNogo-B and hNogo-B.

Expression of NgBR and Nogo-B in zebrafish

The expression of zNgBR and zNogo-B during zebrafish development was examined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The results show that both zNgBR and zNogo-B are maternal genes because zNgBR and zNogo-B mRNA highly expresses before 5 hpf when maternal transcripts are already present in the developing embryo. Both zNgBR and zNogo-B expression fall precipitously after gastrulation (10 hpf) and remains fairly constant from 18-80 hpf. (supplemental Figure 2A-B).

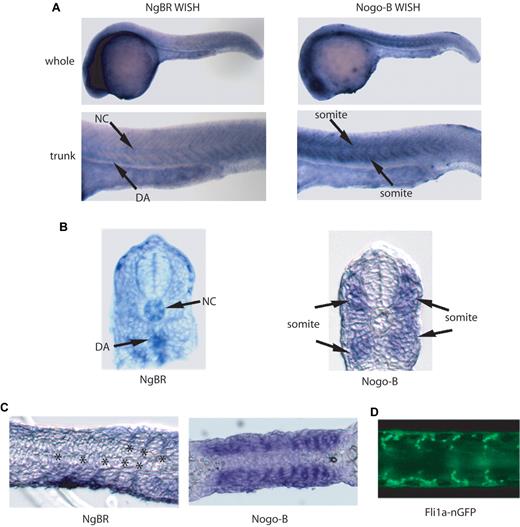

The localization of zNgBR expression was determined by WISH staining (Figure 1 and supplemental Figure 2C) using zNgBR antisense RNA probes. As shown in supplemental Figure 2C, starting at 3 hpf, NgBR RNA is clearly observed in blastomeres. At 12 hpf, expression is ubiquitous in the developing embryo. At 24 hpf, NgBR expression is predominant in the brain and the midline trunk region (Figure 1A). NgBR expression in the notochord and dorsal aorta (DA) of the midline trunk region is clearly visualized in the transverse sections of NgBR WISH (Figure 1B). To determine whether the midline trunk expression is vascular specific, we compared sagittal sections of zNgBR 24 hpf WISH embryos with transgenic fli1a promoter driving green fluorescent protein with nuclear localization signals embryo Tg(fli1a-nGFP). The Tg(fli1a-nGFP) embryos shows GFP expression in both axial and ISVs at 24 hpf.19 The zNgBR expression localizes in between somites (Figure 1C) where endothelial cells are clearly observed in Tg(fli1a-nGFP) flat mounts (Figure 1D). In comparison to other vascular genes such as Syx22 and ESCR23 that function in the developing vasculature, zNgBR follows the similar pattern of low to modest expression in ISVs. As shown in supplemental Figure 2D, zNgBR WISH staining (shown as blue color) is colocalized with the fli1a-GFP immunostaining (shown as red color) in DA. The WISH results show that zNgBR is expressed in both endothelial and neural tissues with vascular expression seen in the ISV and DA.

Expression patterns of NgBR and Nogo-B in zebrafish. (A) Images of NgBR and Nogo-B whole-mount in situ staining (WISH) at 24 hpf. (B) Transverse and (C) sagittal section images of NgBR and Nogo-B WISH at 24 hpf. (D) Flat-mount image of fli1a-nGFP embryos at 24 hpf. NC, notochord; DA, dorsal aorta; ISV, intersomitic vessels. Asterisk indicates location of ISV.

Expression patterns of NgBR and Nogo-B in zebrafish. (A) Images of NgBR and Nogo-B whole-mount in situ staining (WISH) at 24 hpf. (B) Transverse and (C) sagittal section images of NgBR and Nogo-B WISH at 24 hpf. (D) Flat-mount image of fli1a-nGFP embryos at 24 hpf. NC, notochord; DA, dorsal aorta; ISV, intersomitic vessels. Asterisk indicates location of ISV.

Unlike NgBR, Nogo-B expression is predominantly localized in somites in the midline trunk region of 24 hpf embryos as shown in WISH (Figure 1A) and the transverse section of WISH (Figure 1B). In sagittal sectioning of the trunk region, the somitic pattern of Nogo-B staining (Figure 1C) appears different from ISV expression of NgBR and fli1a-nGFP (Figure 1C-D).

NgBR and NogoB mRNAs are successfully targeted using morpholino technology

To evaluate loss of NgBR or Nogo-B function in embryonic zebrafish development, 3 zNgBR MO antisense oligos targeting ATG start codon (MO1), the boundary of exon2/intron2 (MO2) and exon3/intron3 (MO3), respectively, and 2 zNogo-B MO antisense oligos targeting ATG start codon (MO1), the boundary of exon1/intron1 (MO2), respectively, were designed and generated by Gene Tools (supplemental Figure 3A-B). Efficacy of splice zNgBR MOs was confirmed by reverse-transcription PCR across the flanking exons of the targeted splice donor sites, which revealed 2 bands in MO2- and MO3-injected embryos compared with uninjected controls (WT; supplemental Figure 3A). Sequencing the lower band (black arrow, supplemental Figure 3A) in MO2 and MO3 lane revealed the 23-bp deletion in exon2 or 28-bp deletion in exon3, respectively, resulting in the out of frame protein. Bands amplified in the nontargeted regions showed identical sequence similar to common bands in WT lanes (gray arrow, supplemental Figure 3A). Based on supplemental Figure 3A results, the efficacy of MO3 modifying zNgBR expression is higher than MO2. Similarly, efficacy of zNogo-B splice MO2 was confirmed by reverse-transcription PCR across the flanking exons of the targeted splice donor sites, which revealed 2 bands in MO2-injected embryos compared with uninjected controls (WT; supplemental Figure 3B). Sequencing the lower band (black arrow, supplemental Figure 3B) in MO2 lane revealed there are 2 modifications of zNogo-B transcripts. One is an 18-bp deletion in exon1, resulting in the deletion of 6 amino acids (CNSSCS) that is referred to the 179-184 aa of human Nogo-B1, which is part of the crucial functional domain of human Nogo-B1 (183-186 aa) as described in our previous publication.13 The other one is a deletion of 54 bp happened at the boundary of Eoxn2 and Exon3. Bands amplified in the nontargeted regions showed identical sequence similar to common bands in WT lanes (gray arrow, supplemental Figure 3B). These results show that specific MO reagents successfully target both zNogoB and zNgBR transcripts in vivo. Real-time PCR results (supplemental Figure 3C-D) show that zNgBR MO3 and zNogo-B MO2 can reduce the WT transcripts of zNgBR and zNogo-B by 93% and 92%, respectively.

Loss of NgBR and NogoB function in zebrafish is critical for angiogenesis

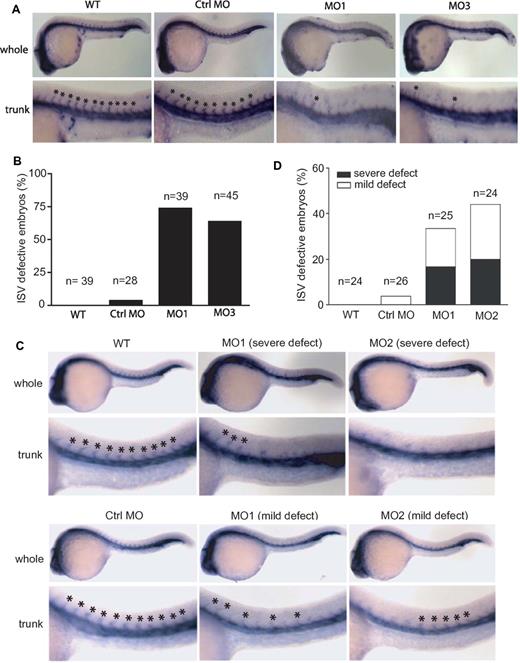

To evaluate the vasculature phenotype in the developing embryos, we performed WISH for friend leukemia integration 1a (fli1a), which marks most vessels of the developing zebrafish embryo at 24 hpf.19 Knockdown of zNgBR by MO targeting ATG (MO1), the intron-exon boundary of Exon 2 (MO2) or Exon3 (MO3), respectively, all impaired ISV formation (lack of ISV) compared with control MO at 24 hpf (Figure 2A). These results are consistent with the efficacy of MOs modifying zNgBR transcripts shown in supplemental Figure 2A. Embryos injected with MO1 and MO3 show stronger ISV defect phenotype than embryos injected with MO2. Therefore, we show data with MO1 and MO3 for the remainder of the studies. Quantification of these defects shows that 72% of MO1-injected embryos and 68% of MO3-injected embryos display a lack of more than 5 ISV in the trunk region (Figure 2B). Control MO did not cause any significant ISV defects compared with uninjected controls (Figure 2A-B). In addition to fli1a, we performed WISH for flk1 as shown in supplemental Figure 4A and B. The results are consistent with fli1a WISH. NgBR MOs result in the loss of flk1-positive ISV in the trunk regions at 24 hpf.

Effects of zNgBR and zNogo-B MO-injection on ISV formation. (A) zNgBR MO blocks ISV formation. Whole-mount fli1a- in situ staining (blue; Fli1a-WISH) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), Ctrl MO- (8 ng control MO), MO1- (8 ng ATG MO), and MO3- (8 ng splice MO) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. (B) Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 5 ISV). n, embryo number in each group. (C) zNogo-B MO causes ISV formation defects. Fli1a-WISH (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO1- (8 ng ATG MO), and MO2- (8 ng splice MO) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. (D) Quantification of embryos with ISV defects. n, embryo number in each group. Severe defect, missing more than 3 ISV in trunk region; mild defect, ISV orientation defect. Anterior is to the left.

Effects of zNgBR and zNogo-B MO-injection on ISV formation. (A) zNgBR MO blocks ISV formation. Whole-mount fli1a- in situ staining (blue; Fli1a-WISH) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), Ctrl MO- (8 ng control MO), MO1- (8 ng ATG MO), and MO3- (8 ng splice MO) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. (B) Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 5 ISV). n, embryo number in each group. (C) zNogo-B MO causes ISV formation defects. Fli1a-WISH (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO1- (8 ng ATG MO), and MO2- (8 ng splice MO) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. (D) Quantification of embryos with ISV defects. n, embryo number in each group. Severe defect, missing more than 3 ISV in trunk region; mild defect, ISV orientation defect. Anterior is to the left.

Similarly, fli1a WISH of zebrafish Nogo-B knockdown using ATG MO (MO1) and splice MO targeting the intron-exon boundary of Exon 1 (MO2), respectively, also showed ISV defects. In some cases, severe phenotype (lack of ISV) or mild phenotype (ISV orientation defect) was observed compared with control MO at 24 hpf (Figure 2C). Quantification of these defects shows that 33% of MO1-injected embryos and 48% of MO2-injected embryos display ISV defects in the trunk region (Figure 2D). Control MO did not cause any significant ISV defects compared with uninjected controls (Figure 2C-D). As shown in Figure 2A and C, embryos injected with the same amount of zNgBR MO1 and MO3 show stronger ISV defect phenotype than embryos injected with zNogo-B MO1 and MO2. Nevertheless, the fact that we noticed similar ISV defects with the loss of zNogoB and zNgBR clearly argues for a specific role of NogoB-NgBR signaling pathway in sprouting angiogenesis in vivo.

In addition to fli1a and flk1 markers at 24 hpf, we also examined the expression and localization of etsrp (vasculogenesis: angioblast marker) at 14 hpf, gata1 (erythroid marker) at 18 hpf, flk1 at 16 hpf (earlier time point) and myod (gastrulation marker) at 24 hpf in zNgBR MO1 and MO3-injected embryos compared with uninjected controls (Figure 3). These results indicated that zNgBR MOs had no effects on zebrafish angioblast proliferation and migration (etsrp at 14 hpf), hematopoietic progenitor cell population and localization (gata1 at 18 hpf), early vasculature development (flk1 at 16 hpf), and somite formation (myod at 24 hpf). Our current study shows that zNgBR MOs only consistently and specifically block ISV formation at 22-24 hpf. Taken together with zNogo-B studies, we conclude that zNogoB-zNgBR is the correct ligand-receptor pair that is responsible for sprouting angiogenesis in vivo.

NgBR MOs have no effects on the early development. Whole-mount in situ staining of etsrp at 14 hpf, gata1 at 18 hpf, flk1 at 16 hpf, and myod at 24 hpf were performed to examine the effects of NgBR MOs on the developments of angioblast (etsrp), hematopoietic progenitor cells (gata1), early vasculature development (flk1), and somite formation (myod). WT, uninjected embryos; MO1, ATG-MO–injected embryos; MO3, splice MO-injected embryos.

NgBR MOs have no effects on the early development. Whole-mount in situ staining of etsrp at 14 hpf, gata1 at 18 hpf, flk1 at 16 hpf, and myod at 24 hpf were performed to examine the effects of NgBR MOs on the developments of angioblast (etsrp), hematopoietic progenitor cells (gata1), early vasculature development (flk1), and somite formation (myod). WT, uninjected embryos; MO1, ATG-MO–injected embryos; MO3, splice MO-injected embryos.

NgBR is necessary for VEGF-induced migration and morphogenesis of endothelial cells

Previously, we have shown that AmNogo-B promotes the migration of endothelial cells via NgBR.13 However, our in vivo results show that zNgBR knockdown caused much severe ISV defect in zebrafish compared with zNogoB knockdown. This indicates that NgBR should have additional regulatory roles beyond in Nogo-B signaling. It suggests that Nogo-B may not be the exclusive stimulator for NgBR, although NgBR is essential for Nogo-B–stimulated endothelial cell migration and morphogenesis. We further elucidated that NgBR is also necessary for VEGF-stimulated endothelial cell motility and morphogenesis.

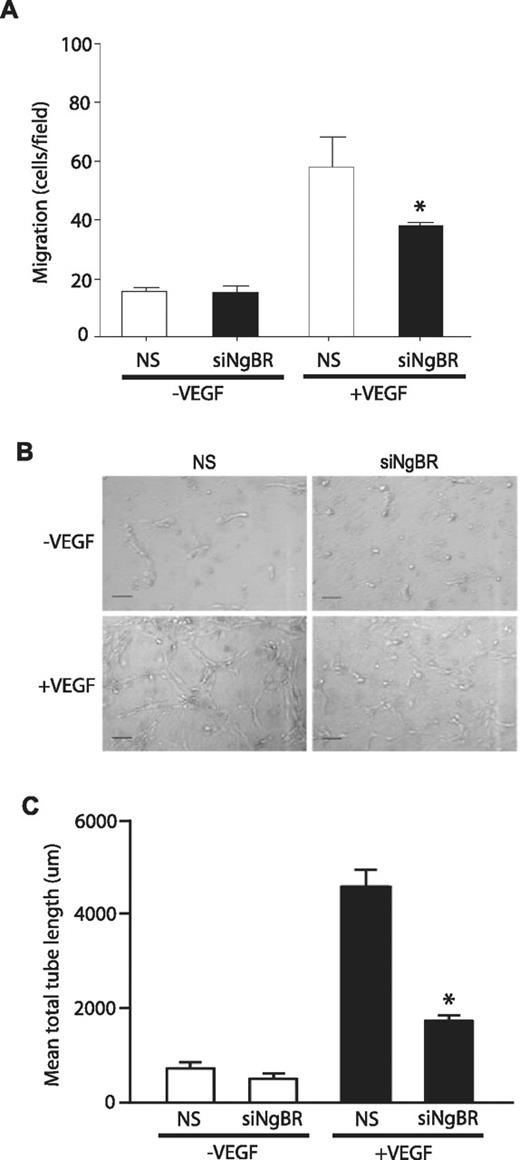

To investigate NgBR loss of function in vitro, we used previously validated NgBR siRNA13 in HUVECs and examined VEGF-stimulated migration of HUVECs using the modified Boyden chamber as previously described.13 NgBR siRNA (siNgBR) specifically knocks down NgBR protein levels by 80%-90% in HUVECs compared with NS siRNA (Figure 5C). NgBR siRNA treatment reduces VEGF-stimulated HUVEC migration but has no effect on basal migration (in the absence of VEGF; Figure 4A). Further, NgBR siRNA treatment also abolished VEGF-induced tube formation in 3D collagen gel model (Figure 4B-C). These results suggest that NgBR may be involved in VEGF-mediated angiogenic signaling pathways.

Effects of NgBR knockdown on VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and morphogenesis. (A) NgBR knockdown abolished VEGF-stimulated migration of HUVECs. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). (B-C) NgBR is necessary for VEGF-induced tube formation. After treatment with either NS or NgBR siRNA, HUVECs were suspended in type I collagen gels and treated with vehicle or 100 ng/mL VEGF. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were photographed (B), and total network length was quantified (C). Representative images (B) are shown for 2 independent experiments (n = 3 in C). Scale bar = 100 μm; *P < .05; siRNA: 10nM.

Effects of NgBR knockdown on VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration and morphogenesis. (A) NgBR knockdown abolished VEGF-stimulated migration of HUVECs. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). (B-C) NgBR is necessary for VEGF-induced tube formation. After treatment with either NS or NgBR siRNA, HUVECs were suspended in type I collagen gels and treated with vehicle or 100 ng/mL VEGF. After 24 hours of incubation, cells were photographed (B), and total network length was quantified (C). Representative images (B) are shown for 2 independent experiments (n = 3 in C). Scale bar = 100 μm; *P < .05; siRNA: 10nM.

We used AP-conjugated VEGF165 (AP-VEGF) as a ligand to examine VEGF binding affinity on the surface of HUVECs after NgBR siRNA treatments. Bound AP or AP-VEGF was detected with Blue Substrate kit (Vector Laboratories), and blue staining indicates positive AP-VEGF binding onto the cell surface (Figure 5A). NgBR siRNA (Figure 5A) did not reduce AP-VEGF binding on the surface of HUVECs compared with NS siRNA. In addition, no background staining was detected in the AP-alone group, suggesting the specificity of AP-VEGF binding on HUVECs. We also extracted bound AP or AP-VEGF with 1% Triton X-100 to quantify AP activity using colorimetric substrate p-nitro-phenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich; Figure 5B). The quantitative results (Figure 5B) also show that bound AP-VEGF activity is identical between HUVECs treated with either NS siRNA or NgBR siRNA, respectively. These results indicate that NgBR knockdown does not affect VEGF binding onto the surface of HUVECs. Western blot analysis of NgBR siRNA transfected cells does not show a change in protein levels of VEGFR2 (Figure 5C) and other neuronal guidance molecules involved in angiogenesis such as Semaphorin 3e, Robo-4, Plexin B2, and Plexin D1 (supplemental Figure 5A) in HUVECs. Also, VEGF-induced phosphorylation of VEGFR2 (Y1175) is unchanged (Figure 5C). Taken together with VEGF binding results, these data suggest that the regulatory effect of NgBR on VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration likely happens at the downstream of VEGF-triggered signaling but not at the level of the cell surface VEGF-VEGFR2 ligand-receptor. Next, we examined known downstream signaling events of VEGFR2 in HUVECs (Figure 5C). We found that NgBR siRNA treatment significantly reduced either VEGF or AmNogo-B–induced phosphorylation of Akt (S473; Figure 5C). Although it is not clear how NgBR interrupts VEGF/AmNogo-B–stimulated phosphorylation of Akt in HUVECs, our previous studies have shown that phosphorylation of Akt is essential for VEGF-stimulated endothelial migration.24,25

Effects of NgBR knockdown on VEGF-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and Akt-dependent endothelial cell migration. (A-B) NgBR knockdown has no effect on AP-VEGF binding on the surface of HUVECs. After 48 hours of treatment with NS siRNA (siRNA-NS) or NgBR siRNA (siRNA-NgBR), HUVECs were incubated with 10nM AP or AP-VEGF at 4°C for 2 hours. AP was applied as controls to determine the nonspecific binding on the HUVEC surface. (A) The bound AP or AP-VEGF was detected using the Blue Substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). (B) The bound AP or AP-VEGF was extracted with Triton X-100, and AP activity was colorimetrically quantified using p-nitro-phenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) as substrate. (C) NgBR knockdown reduced the VEGF/AmNogo-B–stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and ERK in HUVECs. Quiescent siRNA-treated HUVECs was stimulated with 100 ng/mL VEGF/AmNogo-B for 30 minutes. The phosphorylation of Akt (S473) and ERK (p42/44) was determined by Western blot analysis as described in “Western blot analysis.” (D) Constitutively activated myrAkt restores the VEGF-induced migration of HUVECs treated with NgBR siRNA. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). *P < .05, vs NS + VEGF; #P < .05, vs Ctrl + VEGF. (E) NgBR coding-region cDNA restores the VEGF-induced migration of HUVECs treated with NgBR siRNA. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). *P < .05, vs NS + VEGF; #P < .05, vs Vector + VEGF + siNgBR. Vector, transfected with plasmid DNA vector containing the internal ribosome entry site (pIRES)–neo empty vector; NgBR, transfected with pIRES-neo vector carrying NgBR coding-region cDNA. siRNA, 10nM.

Effects of NgBR knockdown on VEGF-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and Akt-dependent endothelial cell migration. (A-B) NgBR knockdown has no effect on AP-VEGF binding on the surface of HUVECs. After 48 hours of treatment with NS siRNA (siRNA-NS) or NgBR siRNA (siRNA-NgBR), HUVECs were incubated with 10nM AP or AP-VEGF at 4°C for 2 hours. AP was applied as controls to determine the nonspecific binding on the HUVEC surface. (A) The bound AP or AP-VEGF was detected using the Blue Substrate kit (Vector Laboratories). (B) The bound AP or AP-VEGF was extracted with Triton X-100, and AP activity was colorimetrically quantified using p-nitro-phenyl phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) as substrate. (C) NgBR knockdown reduced the VEGF/AmNogo-B–stimulated phosphorylation of Akt and ERK in HUVECs. Quiescent siRNA-treated HUVECs was stimulated with 100 ng/mL VEGF/AmNogo-B for 30 minutes. The phosphorylation of Akt (S473) and ERK (p42/44) was determined by Western blot analysis as described in “Western blot analysis.” (D) Constitutively activated myrAkt restores the VEGF-induced migration of HUVECs treated with NgBR siRNA. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). *P < .05, vs NS + VEGF; #P < .05, vs Ctrl + VEGF. (E) NgBR coding-region cDNA restores the VEGF-induced migration of HUVECs treated with NgBR siRNA. Cell migration was examined in modified Boyden chambers in response to VEGF (100 ng/mL; n = 3). *P < .05, vs NS + VEGF; #P < .05, vs Vector + VEGF + siNgBR. Vector, transfected with plasmid DNA vector containing the internal ribosome entry site (pIRES)–neo empty vector; NgBR, transfected with pIRES-neo vector carrying NgBR coding-region cDNA. siRNA, 10nM.

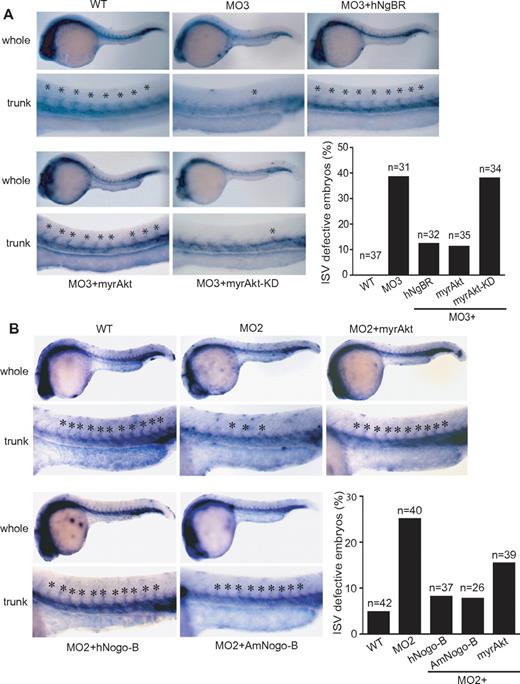

Constitutively activated Akt rescues the angiogenic defect caused by NgBR knockdown

To further explore whether the regulatory function of NgBR on Akt phosphorylation plays a critical role in VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo, we performed rescue experiments with constitutively activated myrAkt (myristoylated and activated Akt/protein kinase B) and myrAkt-KD (a kinase-dead version of myristoylated Akt/protein kinase B), a negative control for myrAkt.26 In vitro results (Figure 5D) showed that myrAkt but not myrAkt-KD partially restored VEGF-induced migration of endothelial cells treated with NgBR siRNA. In addition, transfection of NgBR coding-region cDNA also partially rescued VEGF-induced HUVEC migration (Figure 5E). Expression of NgBR coding-region cDNA in NgBR siRNA-treated HUVECs was detected by Western blot analysis (supplemental Figure 5B). In vivo, ISV defects in zNgBR MO3-injected embryos were also rescued by co-injection of either myrAkt RNA or human NgBR RNA but not by myrAkt-KD (Figure 6A). The quantitative results (Figure 6A) show that injection of either hNgBR or myrAkt RNA decreases ISV defects from 38% in the MO3-alone group (MO injection reduced to 6 ng) to 12% and 10%, respectively. Importantly, myrAkt-KD mutant did not promote rescue. Similarly, injection of myrAkt, human full-length Nogo-B, and AmNogo-B RNA decreases ISV defects in zNogo-B MO2-injected embryos from 25% to 15.4%, 8.1%, and 7.7%, respectively (Figure 6B). Expression of injected myrAkt, Nogo-B, AmNogo-B, and NgBR RNA in zebrafish can be detected by Western blot analysis (supplemental Figure 5C). These results taken together suggest that (1) NgBR modulates endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis via Akt pathway in vitro and in vivo, and (2) NgBR vascular function is evolutionarily conserved.

Constitutively activated Akt (myrAkt) rescues the defects of ISV formation in vivo. (A) Constitutively activated myrAkt rescues the ISV defects caused by zNgBR MO3 injection at 24 hpf embryos. Fli1a-WISH staining (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO3- (6 ng of zNgBR splice MO), MO3 + hNgBR- (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg hNgBR mRNA), MO3 + myrAkt-WT– (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg myrAkt), and MO3 + myrAkt-KD– (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg myrAkt-KD) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 5 ISV). (B) Constitutively activated myrAkt rescues the ISV defects caused by zNogo-B MO2 injection at 24 hpf embryos. Fli1a-WISH staining (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO2- (6 ng of zNogo-B splice MO), MO2 + myrAkt-WT– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg myrAkt), MO2 + hNogo-B– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg human full-length Nogo-B mRNA), and MO2 + AmNogo-B– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg human AmNogo-B) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 3 ISV). Anterior is to the left. myrAkt, myristoylated activated Akt/protein kinase B (PKB); myrAkt-KD, the kinase-dead version of myristoylated Akt/PKB.

Constitutively activated Akt (myrAkt) rescues the defects of ISV formation in vivo. (A) Constitutively activated myrAkt rescues the ISV defects caused by zNgBR MO3 injection at 24 hpf embryos. Fli1a-WISH staining (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO3- (6 ng of zNgBR splice MO), MO3 + hNgBR- (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg hNgBR mRNA), MO3 + myrAkt-WT– (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg myrAkt), and MO3 + myrAkt-KD– (6 ng of MO3 plus 100 pg myrAkt-KD) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 5 ISV). (B) Constitutively activated myrAkt rescues the ISV defects caused by zNogo-B MO2 injection at 24 hpf embryos. Fli1a-WISH staining (blue) was performed to localize the ISV at 24 hpf embryos. Top panels are the images of whole embryos at 24 hpf, and bottom panels are magnified images of the trunk region, showing WT (uninjected), MO2- (6 ng of zNogo-B splice MO), MO2 + myrAkt-WT– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg myrAkt), MO2 + hNogo-B– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg human full-length Nogo-B mRNA), and MO2 + AmNogo-B– (6 ng of MO2 plus 100 pg human AmNogo-B) injected embryos. Asterisk indicates location of ISV. Quantification of embryos with ISV defects (missing more than 3 ISV). Anterior is to the left. myrAkt, myristoylated activated Akt/protein kinase B (PKB); myrAkt-KD, the kinase-dead version of myristoylated Akt/PKB.

Discussion

Our previous publication demonstrated that Nogo-B and NgBR were an essential modulator system for endothelial cell migration in vitro.13 The present study confirms our previous finding in vivo. The salient features of this study include (1) identifying that the zebrafish orthologs of Nogo-B and NgBR are expressed in somite and intersomitic vessel, respectively, during embryonic development; (2) demonstrating Nogo-B and its receptor, NgBR, are the cognate ligand-receptor pair responsible for ISV formation in zebrafish; (3) NgBR also participates in VEGF-mediated endothelial cell migration and morphogenesis in vitro; and finally, (4) Akt phosphorylation is downstream from NgBR and mediates signaling cues necessary for angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo.

In zebrafish, the primary axial vessels, DA and posterior cardinal vein, are formed via a vasculogenesis mechanism.27 In the developing trunk of zebrafish, ISV arises via angiogenic mechanisms and sprouts from existing DA and posterior cardinal vein and extends near somite boundaries. This sprouting process is coordinated in a rostral–caudal direction, and each sprout traverse crosses the midline to reach the dorso-lateral surface and form dorsal longitudinal anastomotic vessels.27 Members of axon guidance family have been shown to participate in ISV sprouting in vivo.4,28-30 For example, the semaphorin family and their plexin receptors have been shown as both neuronal31,32 and blood vessel pathfinding molecules.28 Zebrafish plexin-D1 (plxnD1) is expressed throughout the vasculature in blood vessel endothelial cells and their angioblast precursors33 while loss of plexin-D1 function causes a dramatic mispatterning of ISV.28,29 Semaphorins, specific ligands of plexin receptors, are expressed in somites flanking ISVs, and loss of function causes similar ISV patterning defects.34,35 Recently, Lamont et al showed that loss of Semaphorin3e and plexinB2 (isoforms expressed in endothelial cells) leads to delayed ISV sprouting.30 Our results in this study add the NogoB-NgBR system to this growing list of axon guidance molecules that participate in ISV sprouting. Similar to the semaphorin-plexin system, the zebrafish orthologs of Nogo-B (zNogo-B) are mainly expressed in somites flanking ISVs of zebrafish, while receptor NgBR (zNgBR) is expressed in ISV and DA of zebrafish. This pattern is also reminiscent of the VEGF-VEGF receptor (VEGFR) family,36 where VEGF-A is expressed in the somites, and VEGFR flt1 and flk1 are localized in the ISV and DA of zebrafish.36 However, unlike the guidance function of plexin-D1 and semaphorins, loss of either NgBR or NogoB in zebrafish mainly causes loss of ISV (Figure 2), which may be, in part, because loss of a guidance cue to sprout similar to that observed in Robo44,30,37 or because ineffective sprouting mechanisms result in loss of ISV sprouts. Moreover, like VEGF-A/flk1 knockdown in zebrafish,36 NogoB/NgBR knockdown causes ISV defects with no effect on axial vessel formation, thus arguing that NogoB-NgBR function is dispensable for early vasculogenesis. In line with this hypothesis are data that NgBR knockdown does not affect angioblast proliferation and migration (etsrp at 14 hpf) or early vasculature development (flk1 at 16 hpf; Figure 3).

Previous reports11,38 demonstrated that the amino terminus of Nogo-B (AmNogo-B) is extracellular. AmNogo-B promotes migration of endothelial cells.11 Furthermore, using AmNogo-B as a ligand, we identified its receptor (NgBR) that is necessary for AmNogo-B–induced chemotaxis of endothelial cells.13 These results support the conclusion that AmNogo-B is a functional extracellular domain of Nogo-B. In supplemental Figure 6A, we demonstrate that siRNA knockdown of Nogo-B in endothelial cells does not affect the basal migration of HUVECs. This result indicates that Nogo-B is not in cis/trans fashion to bind to adjacent NgBR or NgBR on adjacent cells. We speculate that NgBR only responds to soluble AmNogo-B. Although the mechanism of releasing soluble AmNogo-B is unclear, soluble AmNogo-B can be detected in human plasma.39 In addition, we demonstrated that either full-length human Nogo-B or amino terminus of human Nogo-B rescued the ISV defect in zebrafish embryos injected with zNogo-B MO (Figure 6B).

The similarities of the VEGF/flk1 and NogoB/NgBR systems in zebrafish prompted us to investigate whether interplay occurs between the 2 systems in the developing vasculature. Interestingly, NgBR knockdown does not affect VEGF binding on endothelial cell surfaces, VEGFR2/flk1 protein levels, and phosphorylation of VEGFR2 (Y1175), a major tyrosine phosphorylation site in the cytoplasmic domain of VEGFR2 for angiogenic signaling.40 However, NgBR knockdown significantly reduced VEGF-stimulated phosphorylation of Akt (Figure 5C). VEGF-dependent activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt is essential for endothelial cell migration and survival40 and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo.41 Constitutively activated Akt is sufficient to cause cellular chemokinesis, most likely because of its effects on stress fiber formation.24 In vivo, constitutively activated myrAkt can rescue ISV defects caused by VEGFR inhibitor PTK787 in zebrafish.26 Similarly, here, we show that myrAkt can rescue the inhibitory effect of NgBR knockdown on VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration in vitro (Figure 5D) and ISV formation in vivo (Figure 6A). The molecular mechanism of how NgBR modulates VEGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt and importantly VEGF-induced signaling still needs further investigation.

Our current working model is that Nogo-B and/or VEGF-A in somites act as a chemoattractant to trigger the migration of NgBR-positive cells from primary axial vessels to intersomitic regions to eventually form an ISV. If we hypothesize the redundant functional role of Nogo-B and/or VEGF-A as chemoattractant for endothelial cells expressing NgBR, then knockdown of either Nogo-B or VEGF-A (ligand) should only partially impair the ISV sprouting, which is precisely what we observed. As shown in Figure 2, NgBR knockdown has more pronounced phenotype than Nogo-B knockdown alone because NgBR is required for both Nogo-B and VEGF-induced ISV formation. However, because VEGF does not bind to NgBR (Figure 5A-B), the question remains, how is VEGF-induced Akt activation reduced in NgBR knockdown cells?

Previous reports showed that the loss of NgBR increases intracellular free cholesterol levels,42 and increasing free cholesterol inhibits mammalian target of rapamycin activation in endothelial cells.43 To test the hypothesis that increased free cholesterol levels may impair VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration, we treated HUVECs with either U18666A or imipramine overnight to increase intracellular free cholesterol levels as shown in previous publication.43 The results (supplemental Figure 6B-C) showed that U18666A and imipramine treatments only impaired basal migration at the concentration of 10μM and 30μM, respectively, but did not significantly inhibit the VEGF-induced migration as NgBR knockdown did (Figure 4A). this suggests that free cholesterol accumulation should not be the major contribution to impair VEGF-induced endothelial cell migration.

The favored hypothesis is that crosstalk exists between NgBR and VEGFR2 signaling pathways in that they share downstream molecules such as Ras to trigger phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway in endothelial cells. VEGF-stimulated Ras activation in HUVECs has been coupled to an angiogenic phenotype of endothelial cells.44,45 The cytoplasmic domain of NgBR has a high degree of similarity (49%) to the Cis-isoprenyl diphosphate synthases family of lipid modifying enzymes,46,47 transferring isopentenyl diphosphate to farnesyl- or geranyl-diphosphate to form polyprenyl diphosphates. Our previous results showed that lipid transferase activity of NgBR is negative.13 We hypothesize that the hydrophobic cytoplasmic domain of NgBR may act as a scaffold for the binding of isoprenyl lipids and/or prenylated proteins such as Ras-like Galectin-1,48,49 which has a farnesyl-binding pocket and binds farnesylated H-Ras. We will confirm this hypothesis in our future investigation.

In the present study, we consolidated our previous in vitro finding that NgBR is required for in vivo angiogenesis by demonstrating that the NogoB-NgBR ligand-receptor system is responsible for developmental angiogenesis in zebrafish. Here, we show that NgBR is necessary for both Nogo-B and VEGF-induced angiogenesis via downstream Akt activation in endothelial cells. Identification of how NgBR modulates Nogo-B and VEGF signaling will allow for the development of specific agonists and/or antagonists to block neo-angiogenic signals in pathological angiogenesis.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Suresh Kumar of CRI imaging core for assistance with microscopy and Dr Kirkwood Pritchard for manuscript revision.

This work was supported by start-up funds from Division of Pediatric Surgery and Division of Pediatric Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) and Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment to MCW, a SDG grant (0730079N) from American Heart Association to R.Q.M., grants AHW 5520106 (MCW) and HL090712 from the National Institutes of Health to R.R., and seed funds from the Children's Research Institute at MCW to G.A.W.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: B.Z., C.C., R.R., and R.Q.M. designed research; B.Z., C.C., Z.L., and M.A.H. maintained zebrafish; K.P. performed research; G.A.W. contributed reagents/analytical tools; B.Z., C.C., R.R., and R.Q.M. analyzed data; R.Q.M. wrote the paper; and R.R. revised the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Robert Qing Miao, Division of Pediatric Surgery and Division of Pediatric Pathology, Department of Surgery and Department of Pathology, Medical College of Wisconsin, Children's Research Institute, 8701 Watertown Plank Rd, Milwaukee, WI 53226; e-mail: qmiao@mcw.edu.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal