Abstract

Reprogramming blood cells to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) provides a novel tool for modeling blood diseases in vitro. However, the well-known limitations of current reprogramming technologies include low efficiency, slow kinetics, and transgene integration and residual expression. In the present study, we have demonstrated that iPSCs free of transgene and vector sequences could be generated from human BM and CB mononuclear cells using nonintegrating episomal vectors. The reprogramming described here is up to 100 times more efficient, occurs 1-3 weeks faster compared with the reprogramming of fibroblasts, and does not require isolation of progenitors or multiple rounds of transfection. Blood-derived iPSC lines lacked rearrangements of IGH and TCR, indicating that their origin is non–B- or non–T-lymphoid cells. When cocultured on OP9, blood-derived iPSCs could be differentiated back to the blood cells, albeit with lower efficiency compared to fibroblast-derived iPSCs. We also generated transgene-free iPSCs from the BM of a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). CML iPSCs showed a unique complex chromosomal translocation identified in marrow sample while displaying typical embryonic stem cell phenotype and pluripotent differentiation potential. This approach provides an opportunity to explore banked normal and diseased CB and BM samples without the limitations associated with virus-based methods.

Introduction

The advent of reprogramming technology has opened up the possibility of obtaining patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) for the study of blood diseases and for potential therapeutic applications. Although skin fibroblasts initially were used to obtain human iPSCs,1,2 several studies demonstrated successful reprogramming of CD34+ cells from CB or mobilized peripheral blood.3,4 Recently, T cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells have also been successfully reprogrammed to iPSCs.5-7 Because genetic abnormalities are limited to hematopoietic cells in many blood diseases, successful reprogramming of blood cells represents a major advance in establishing iPSC-based models for hematologic diseases. However, because the current reprogramming methods use virus-based delivery of reprogramming factors, permanent integration of transgene and/or vector sequences into the genome, residual transgene expression, low efficiency, and slow kinetics remain the major problems surrounding this technology. To overcome these problems, several approaches have been used, including transient transfection, RNA transfection, the “PiggyBac” system, protein transduction, the Cre-LoxP excision system, minicircle vectors, and episomal plasmids.8-13 Nevertheless, limitations related to low reprogramming efficiency and/or genomic integration and complexity of genetic manipulations are still not completely resolved, and the suitability of these newest techniques for blood reprogramming remains unknown.

We recently developed a method for obtaining human iPSCs free of vector and transgene sequences from human fibroblasts using nonintegrating episomal vectors.14 In the present study, we have demonstrated that this technology could be applied to efficiently reprogram mononuclear cells from human BM and CB to pluripotency with up to 100 times more reprogramming efficiency compared with fibroblasts. The iPSCs generated by this method were free of transgene and vector sequences and were able to differentiate back to the blood, albeit with lower efficiency compared with fibroblast-derived iPSCs. Using the same protocol, we also efficiently reprogrammed a BM sample from a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and were able to obtain transgene-free iPSCs with unique, patient-specific complex chromosomal translocation, which would be impossible to generate using currently available genetic-engineering methods. The elimination of genomic integration and background transgene expression, some of which are oncogenes, is a critical step toward advancing iPSC technology for the modeling of blood diseases and therapeutic applications.

Methods

iPSC culture

The human embryonic stem cell (hESC) line H1 (NIH code WA01) was obtained from WiCell. Transgene-free fibroblast-derived iPSC lines DF19-9-7T, DF19-9-11T, DF19-9, DF4-3-7T, DF6-9, and DF6-9-9T were derived using nonintegrating episomal vectors to express the OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28, MYC, KLF4, and LT (SV40 large T gene) reprogramming factors, as described previously.14 DF19 iPSC lines were obtained by transfection of foreskin fibroblasts with a combination of pEP4EO2SET2K (OCT4/SOX2/LT/KLF4), pEP4EO2SEN2K (OCT4/SOX2/NANOG/KLF4), and pCEP4-M2L (MYC/LIN28) plasmids. DF6 iPSC lines were obtained by transfection of foreskin fibroblasts with a combination of pEP4EO2SEN2L (OCT4/SOX2/NANOG/LIN28), pEP4EO2SET2K (OCT4/SOX2/LT/KLF4), and pEP4EO2SEM2K (OCT4/SOX2/MYC/KLF4) plasmids. The DF4-3-7T cell line was obtained using a combination of pEP4EO2SCK2MEN2L (OCT4/SOX2/KLF4/MYC/NANOG/LIN28) and pEP4EO2SET2K (OCT4/SOX2/LT/KLF4) plasmids. hESCs and iPSCs were maintained as undifferentiated cells in cocultures with mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).2,14,15

Generation of iPSCs from mononuclear cells

Frozen CB mononuclear cells were obtained from AllCells. BM mononuclear cells from normal donors and from a patient with CML in the chronic phase were purchased from AllCells. Total BM cells intended for final disposition were also obtained from the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics. Whole BM was cultured overnight in expansion medium consisting of StemSpan SFEM (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with Ex-Cyte (0.2%; Celliance) and recombinant human IL-3 (10 ng/mL), IL-6 (100 ng/mL), SCF (100 ng/mL), and FMS-related tyrosine kinase-3 ligand (Flt3L;100 ng/mL; all from PeproTech). The next day, Histopaque (Sigma-Aldrich) separation was performed to obtain the mononuclear cells. For reprogramming, BM mononuclear cells were cultured in expansion medium for 2 days (Figure 1A). After removing the dead cells by spinning over a 20% Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich), 1 × 105 to 3.7 × 106 viable cells were transfected with combination 19 of reprogramming factors (9 μg of pEP4EO2SET2K and pEP4EO2SEN2K and 6 μg of pCEP4M2L)14 using the CD34+ Nucleofector kit (Lonza). After an additional 2 days of culturing in expansion medium and removing the dead cells by Percoll density centrifugation, cells were transferred onto MEFs and cultured in iPSC medium. Starting from day 10, MEF-conditioned medium was used, and this was changed every day. The individual iPSC colonies were picked up for expansion from days 17-21. CB mononuclear cells were reprogrammed using the same conditions with or without the addition of 1μM thiazovivin (Stemgent).

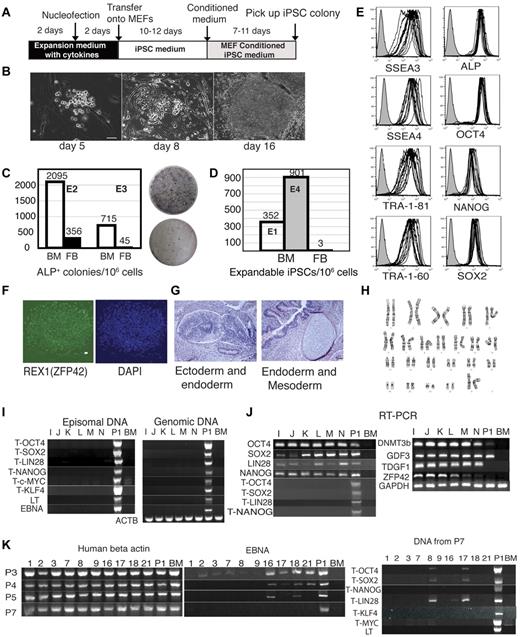

Efficient generation of transgene-free iPSCs from BM mononuclear cells. (A) Schematic diagram of reprogramming protocol. (B) Kinetics of morphologic changes after blood reprogramming. (C-D) Comparison of reprogramming efficiency between blood cells and fibroblasts. (C) Left graph shows the numbers of ALP+ colonies per 1 million BM cells and fibroblasts (FB) transfected side by side with combination 19 episomal vectors. Two independent experiments, E2 and E3, are shown. Right panel shows ALP staining of colonies generated after transfection and the first passage on MEFs 2 × 105 BM cells (top) and 3.3 × 105 fibroblasts (bottom). (D) Expandable iPSC colonies obtained from 1 million FB and BM cells transfected with the same set of reprogramming factors. Black bar shows the number of iPSC colonies generated from foreskin fibroblasts in our previous studies.14 Bars in E1 and E4 show results of reprogramming of BM mononuclear cells from 2 independent experiments (E1 and E4). (E) Flow cytometric analysis of hESC-specific marker expression in 7 BM iPSC lines and 6 subclones generated from BM iPSC1. (F) Representative immunofluorescent staining of BM iPSCs with REX1 antibody. Bar indicates 50 μm. (G) H&E staining of teratoma from representative BM iPSC line (BM iPSC1M). Neuronal rosette and gastro-intestine-like structure can be seen in the left panel. Cartilage and gut epithelium can be seen in the right panel. Bars indicate 50 μm. (H) Normal karyogram representative of BM iPSC (BM iPSC1M). (I) PCR analysis of episomal and genomic DNA in subclones I-N obtained from the BM iPSC1 line. Human BM genomic DNA serves as negative control (BM), whereas DNA samples from human BM mononuclear cells transfected with the same constructs are used as a positive control (P1). T indicates that transgene specific primers were used. (J) RT-PCR analysis of expression of transgenes and endogenous pluripotency genes in subclones I-N obtained from the BM iPSC1 line. The T series of primers are transgene-specific. Negative controls (BM) are results of untransfected BM RNA. Positive controls (P1) are BM cells transfected with the same reprogramming plasmids. (K) Progressive loss of episomal plasmid from BM iPSC lines. Ten randomly selected BM iPSC lines (1-3, 7-9, 16-18, and 21) were analyzed. Vector-specific primer pairs (EBNA, middle panel) were used to examine the episomal DNA from different passages (passage 3, 4, 5, and 7) of the BM iPSC lines. Samples of passage 7 were further examined by other transgene-specific primers (right panel). Left panel shows existence of genomic DNA (human actin genomic primers) in the episomal DNA extracted using the previously published method.16

Efficient generation of transgene-free iPSCs from BM mononuclear cells. (A) Schematic diagram of reprogramming protocol. (B) Kinetics of morphologic changes after blood reprogramming. (C-D) Comparison of reprogramming efficiency between blood cells and fibroblasts. (C) Left graph shows the numbers of ALP+ colonies per 1 million BM cells and fibroblasts (FB) transfected side by side with combination 19 episomal vectors. Two independent experiments, E2 and E3, are shown. Right panel shows ALP staining of colonies generated after transfection and the first passage on MEFs 2 × 105 BM cells (top) and 3.3 × 105 fibroblasts (bottom). (D) Expandable iPSC colonies obtained from 1 million FB and BM cells transfected with the same set of reprogramming factors. Black bar shows the number of iPSC colonies generated from foreskin fibroblasts in our previous studies.14 Bars in E1 and E4 show results of reprogramming of BM mononuclear cells from 2 independent experiments (E1 and E4). (E) Flow cytometric analysis of hESC-specific marker expression in 7 BM iPSC lines and 6 subclones generated from BM iPSC1. (F) Representative immunofluorescent staining of BM iPSCs with REX1 antibody. Bar indicates 50 μm. (G) H&E staining of teratoma from representative BM iPSC line (BM iPSC1M). Neuronal rosette and gastro-intestine-like structure can be seen in the left panel. Cartilage and gut epithelium can be seen in the right panel. Bars indicate 50 μm. (H) Normal karyogram representative of BM iPSC (BM iPSC1M). (I) PCR analysis of episomal and genomic DNA in subclones I-N obtained from the BM iPSC1 line. Human BM genomic DNA serves as negative control (BM), whereas DNA samples from human BM mononuclear cells transfected with the same constructs are used as a positive control (P1). T indicates that transgene specific primers were used. (J) RT-PCR analysis of expression of transgenes and endogenous pluripotency genes in subclones I-N obtained from the BM iPSC1 line. The T series of primers are transgene-specific. Negative controls (BM) are results of untransfected BM RNA. Positive controls (P1) are BM cells transfected with the same reprogramming plasmids. (K) Progressive loss of episomal plasmid from BM iPSC lines. Ten randomly selected BM iPSC lines (1-3, 7-9, 16-18, and 21) were analyzed. Vector-specific primer pairs (EBNA, middle panel) were used to examine the episomal DNA from different passages (passage 3, 4, 5, and 7) of the BM iPSC lines. Samples of passage 7 were further examined by other transgene-specific primers (right panel). Left panel shows existence of genomic DNA (human actin genomic primers) in the episomal DNA extracted using the previously published method.16

PCR analysis of episomal and genomic DNA and RT-PCR

Episomal DNA was prepared according to a previously published method.16 Genomic DNA was extracted per the manufacturer's instructions using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Because of the nature of the purification methods, the genomic DNA samples were likely contaminated with residual amounts of episomal DNA from the same cells, and the episomal DNA preparations were likely contaminated with small amounts of genomic DNA (see the presence of the ACTB signal in the episomal DNA fraction in Figure 1K). RNA was purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) or with TRI Reagent Solution (Ambion). The iPSCs from 2 wells of a 6-well plate were used for each preparation of RNA, DNA, and episomal fraction of DNA. Two micrograms of total RNA were used in each reaction of the synthesis of the first strand of cDNA with Advantage RT-for-PCR Kit (Clontech). The cDNA was diluted 6 times, and 3 microliters of the diluted cDNA were used for RT-PCR analysis. All primers used in these studies are listed in Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| Gene . | Primer name . | Sequence . | Direction . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POU5F1 | 60OCT4F1 | GAGGAGTCCCAGGACATCAA | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| SOX2 | 60SOXR1 | TCATGTAGGTCTGCGAGCTG | R | TGS |

| 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | F | ||

| NANOGg | 60NANOGF1 | TTCCTTCCTCCATGGATCTG | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| LIN28 | 60LinR | CTGCCTCACCCTCCTTCAA | F | TGS |

| 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | R | ||

| c-MYC | 60MYCF1 | AGAGAAGCTGGCCTCCTACC | F | TGS |

| 60IRES2R | CCCTAGGAATGCTCGTCAAG | R | ||

| KLF4 | 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | F | TGS |

| 60KLF-R1 | TGCTCAGCACTTCCTCAAGA | R | ||

| Large-T | 60LTf1 | TTAATTTGCCCTTGGACAGG | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| EBNA | 60ORI-F1 | TTTTCGCTGCTTGTCCTTTT | F | TGS |

| 60EBNAr | TTCCAACCCGAAATTTGAGA | R | ||

| ACTB | HuACTBex3F | GTGATGGTGGGCATGGGTCAGAA | F | Control |

| HuACTBex4R | AAGAGTGCCTCAGGGCAGCGGAA | R | ||

| NANOG | NANOGf | TTCCTTCCTCCATGGATCTG | F | cDNA |

| NANOGgr | ATTGTTCCAGGTCTGGTTGC | R | ||

| POU5F1 | OCT4-F2 | AGTTTGTGCCAGGGTTTTTG | F | cDNA |

| OOCT4-R2 | ACTTCACCTTCCCTCCAACC | R | ||

| SOX2 | SOXf | AGAACCCCAAGATGCACAAC | F | cDNA |

| SOXr | GCGAGTAGGACATGCTGTAGG | R | ||

| LIN28 | LINf | CGGGCATCTGTAAGTGGTTC | F | cDNA |

| LINr | GTAGGTTGGCTTTCCCTGTG | R | ||

| ZFP42 | ZFP42F | TGCTCACAGTCCAGCAGGTGTTT | F | cDNA |

| ZFP42R | TCTGGTGTCTTGTCTTTGCCCGTT | R | ||

| DNMT3B | DNMT3bf | AAGTCGAAGGTGCGTCGTGC | F | cDNA |

| DNMT3br | CCCCTCGGTCTTTGCCGTTGT | R | ||

| BCR-ABL | BCL-1 | GCACAGCCGCAACGGCAA | F | cDNA |

| ABL-1 | GAGAAGGTTTTCCTTGGAGTT | R | ||

| GDF3 | GDF3F | TTGGCTTTCAGCTTCCTGTT | F | cDNA |

| GDF3R | CTGACCGCAACACAAACATT | R | ||

| TDGF1 | TDGF1F | ATTTCTACCCGGCTGTGATG | F | cDNA |

| TDGF1R | CCAGTTACTTGGGAGGCTGA | R | ||

| GAPDH | HuGAPDHex4F | GTTTACATGTTCCAATATGATTCCAC | F | Control |

| HuGAPDHex6R | CTGATGATCTTGAGGCTGTTGTCA | R |

| Gene . | Primer name . | Sequence . | Direction . | Notes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POU5F1 | 60OCT4F1 | GAGGAGTCCCAGGACATCAA | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| SOX2 | 60SOXR1 | TCATGTAGGTCTGCGAGCTG | R | TGS |

| 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | F | ||

| NANOGg | 60NANOGF1 | TTCCTTCCTCCATGGATCTG | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| LIN28 | 60LinR | CTGCCTCACCCTCCTTCAA | F | TGS |

| 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | R | ||

| c-MYC | 60MYCF1 | AGAGAAGCTGGCCTCCTACC | F | TGS |

| 60IRES2R | CCCTAGGAATGCTCGTCAAG | R | ||

| KLF4 | 60IRES3F | TGGCTCTCCTCAAGCGTATT | F | TGS |

| 60KLF-R1 | TGCTCAGCACTTCCTCAAGA | R | ||

| Large-T | 60LTf1 | TTAATTTGCCCTTGGACAGG | F | TGS |

| IRES2-SR | AGGAACTGCTTCCTTCACGA | R | ||

| EBNA | 60ORI-F1 | TTTTCGCTGCTTGTCCTTTT | F | TGS |

| 60EBNAr | TTCCAACCCGAAATTTGAGA | R | ||

| ACTB | HuACTBex3F | GTGATGGTGGGCATGGGTCAGAA | F | Control |

| HuACTBex4R | AAGAGTGCCTCAGGGCAGCGGAA | R | ||

| NANOG | NANOGf | TTCCTTCCTCCATGGATCTG | F | cDNA |

| NANOGgr | ATTGTTCCAGGTCTGGTTGC | R | ||

| POU5F1 | OCT4-F2 | AGTTTGTGCCAGGGTTTTTG | F | cDNA |

| OOCT4-R2 | ACTTCACCTTCCCTCCAACC | R | ||

| SOX2 | SOXf | AGAACCCCAAGATGCACAAC | F | cDNA |

| SOXr | GCGAGTAGGACATGCTGTAGG | R | ||

| LIN28 | LINf | CGGGCATCTGTAAGTGGTTC | F | cDNA |

| LINr | GTAGGTTGGCTTTCCCTGTG | R | ||

| ZFP42 | ZFP42F | TGCTCACAGTCCAGCAGGTGTTT | F | cDNA |

| ZFP42R | TCTGGTGTCTTGTCTTTGCCCGTT | R | ||

| DNMT3B | DNMT3bf | AAGTCGAAGGTGCGTCGTGC | F | cDNA |

| DNMT3br | CCCCTCGGTCTTTGCCGTTGT | R | ||

| BCR-ABL | BCL-1 | GCACAGCCGCAACGGCAA | F | cDNA |

| ABL-1 | GAGAAGGTTTTCCTTGGAGTT | R | ||

| GDF3 | GDF3F | TTGGCTTTCAGCTTCCTGTT | F | cDNA |

| GDF3R | CTGACCGCAACACAAACATT | R | ||

| TDGF1 | TDGF1F | ATTTCTACCCGGCTGTGATG | F | cDNA |

| TDGF1R | CCAGTTACTTGGGAGGCTGA | R | ||

| GAPDH | HuGAPDHex4F | GTTTACATGTTCCAATATGATTCCAC | F | Control |

| HuGAPDHex6R | CTGATGATCTTGAGGCTGTTGTCA | R |

TGS indicates primer pairs for transgene specific sequences; and cDNA, primer pairs in cDNA sequences that can recognize endogenous expression of the corresponding genes.

Microarray analysis

Human genome U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip arrays (Affymetrix) were used for microarray hybridizations to examine the global gene expression of human ESCs, iPSCs, foreskin fibroblasts, and BM. The GeneChip carries 54 675 probe sets, which corresponds to 51 337 accession numbers based on the hgu133plus2 annotation package. All samples were processed at the Gene Expression Center of the Biotechnology Center at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, as described previously.14

Hierarchical cluster analyses were carried out with 1-PCC (Pearson correlation coefficient) as the distance measurement. The maximum distance between cluster members was used as the basis to merge lower-level clusters (complete linkage) into higher-level clusters. To visualize the gene-expression levels, the heat-map was composed using MultiExperiment Viewer v4.2 (http://www.tm4.org). The microarray data are deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE26672).

Flow cytometry, immunofluorescence, and cytochemical analyses

Cell-surface staining was done using the antibodies listed in Table 2. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed for 10 minutes at 37°C in Cytofix buffer (BD Biosciences), and then permeated on ice for 30 minutes in cold Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences). After washing, cells were stained at 4°C for 2 hours with antibodies (Table 2). Cells were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For detection of pluripotency markers by immunofluoresence, cells grown in 24-well plates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with ice-cold 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS, and stained overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies followed by a secondary fluorochrome-labeled antibody. 4′,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride staining was performed for nuclei visualization for 10 minutes before image acquisition. Substrate staining for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was carried out using an ALP-staining kit (Stemgent).

Antibodies and the related reagents used in this study

| Antigen . | Label . | Catalog no. . | Source . | Application . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRA-1-81 | PE | 09-0012 | Stemgent | FACS |

| TRA-1-60 | PE | 09-0009 | Stemgent | FACS |

| SSEA-3 | PE | 09-0044 | Stemgent | FACS |

| SSEA-4 | PE | 09-0003 | Stemgent | FACS |

| Rat IgM, κ isotype control | PE | 09-0013 | Stemgent | FACS |

| Mouse IgM, κ isotype control | PE | 09-0002 | Stemgent | FACS |

| APC anti–hTRA-1-85 | APC | FAB3195A | R&D Systems | FACS |

| CD45 | PE | 555483 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| CD43 | PE | 560199 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| CD34 | PE | 555822 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Oct3/4 | PE | 560186 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| SOX2 | PE | 560291 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| NANOG | PE | 560483 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | FITC | 554679 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | PE | 554680 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | APC | 554681 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG2a isotype control | PE | 551438 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| REX1 | None | 09-0019 | Stemgent | IF |

| OCT4 | None | 09-0023 | Stemgent | IF |

| SOX2 | None | 09-0024 | Stemgent | IF |

| Nanog | None | 09-0020 | Stemgent | IF |

| Goat anti–rabbit IgG | DyLight 488 | 09-0034 | Stemgent | IF |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Biotin | BAM1448 | R&D Systems | FACS |

| Streptavidin | PE | 12-4317 | eBioscience | FACS |

| CD29 | FITC | CD2901 | Caltag | FACS |

| CD29 | PE | CD2904 | Caltag | FACS |

| CD90 | APC | 559869 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG3, κ isotype control | PE | 401308 | BioLegend | FACS |

| Antigen . | Label . | Catalog no. . | Source . | Application . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRA-1-81 | PE | 09-0012 | Stemgent | FACS |

| TRA-1-60 | PE | 09-0009 | Stemgent | FACS |

| SSEA-3 | PE | 09-0044 | Stemgent | FACS |

| SSEA-4 | PE | 09-0003 | Stemgent | FACS |

| Rat IgM, κ isotype control | PE | 09-0013 | Stemgent | FACS |

| Mouse IgM, κ isotype control | PE | 09-0002 | Stemgent | FACS |

| APC anti–hTRA-1-85 | APC | FAB3195A | R&D Systems | FACS |

| CD45 | PE | 555483 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| CD43 | PE | 560199 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| CD34 | PE | 555822 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Oct3/4 | PE | 560186 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| SOX2 | PE | 560291 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| NANOG | PE | 560483 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | FITC | 554679 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | PE | 554680 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG1κ isotype control | APC | 554681 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG2a isotype control | PE | 551438 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| REX1 | None | 09-0019 | Stemgent | IF |

| OCT4 | None | 09-0023 | Stemgent | IF |

| SOX2 | None | 09-0024 | Stemgent | IF |

| Nanog | None | 09-0020 | Stemgent | IF |

| Goat anti–rabbit IgG | DyLight 488 | 09-0034 | Stemgent | IF |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Biotin | BAM1448 | R&D Systems | FACS |

| Streptavidin | PE | 12-4317 | eBioscience | FACS |

| CD29 | FITC | CD2901 | Caltag | FACS |

| CD29 | PE | CD2904 | Caltag | FACS |

| CD90 | APC | 559869 | BD Biosciences | FACS |

| Mouse IgG3, κ isotype control | PE | 401308 | BioLegend | FACS |

Karyotyping and teratoma test

Standard G-banded and SKY spectral karyotyping17 were carried out and interpreted by the WiCell Cytogenetics Laboratory (Madison, WI). For teratoma induction, iPSCs at day 5 of culture were passaged into a 10-cm MEF feeder dish. After 3 days of culture, cells were harvested, resuspended in 100 μL of 30% Matrigel in DMEM and Ham F-12 nutrient mixture, and injected into muscle in the hind leg or in the subcutaneous space of NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1wjl/SzJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory). Teratoma was harvested at 8-12 weeks. These experiments were approved by the University of Wisconsin Animal Care and Use Committee.

Differentiation of iPSCs in OP9 coculture and evaluation of hematopoietic potential

Hematopoietic differentiation in coculture with OP9 and analysis of blood production were performed as described previously.18,19 MethoCult GF+ complete methylcellulose medium with FBS and cytokines (SCF, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, and EPO; StemCell Technologies) was used for detection of colony-forming cells.

TCR and IGH rearrangement assays

The PCR-based IG/TCR gene rearrangement assay was performed using genomic DNA and TCRB, TCRG, and IGH clonality assay kits from InVivoScribe Technologies, which use BIOMED-2 primer sets.20 PCR amplification was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions using AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase (Applied Biosystems). The different-sized amplicon products were detected using agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining.

Results

High efficiency of reprogramming of mononuclear cells from human BM and CB

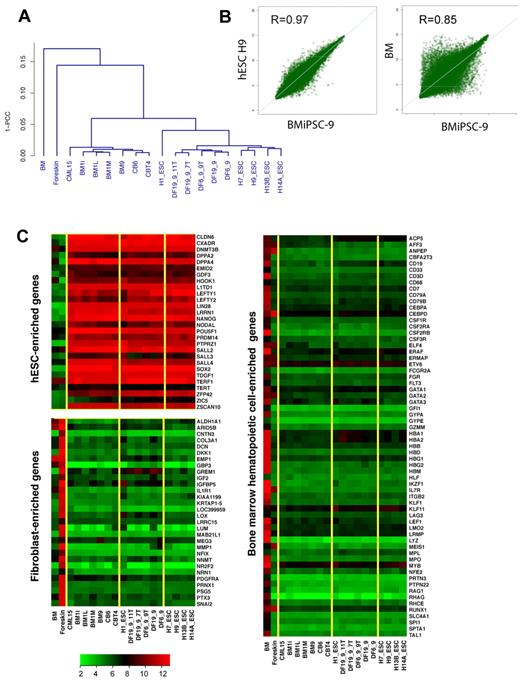

For the production of iPSCs, BM mononuclear cells were cultured in serum-free expansion medium supplemented with human SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and Flt3L for 2 days to expand hematopoietic progenitors, and transfected with episomal vectors (combination 19)14 by nucleofection. After an additional 2 days of culture in hematopoietic medium, floating cells were transferred onto MEF feeders (Figure 1A). Cells in coculture underwent a series of changes, including morphologic transformation from round to cuboidal shape, with eventual formation of ALP+ colonies with typical ESC morphology at approximately day 17-21 of culture (Figure 1B-C). By picking up 50 of 88 high-quality iPSC colonies, we were able to obtain 47 iPSC lines in a single reprogramming experiment, representing 352 iPSC lines per 106 transfected cells. This high reprogramming efficiency of blood cells was reproduced in another experiment (Figure 1D). In contrast, we obtained only a few iPSC lines by transfection of 106 fibroblasts with episomal plasmids expressing the same set of reprogramming factors.14 To confirm superior efficiency of BM-cell reprogramming, we performed side-by-side reprogramming experiments with BM mononuclear cells and neonatal fibroblasts and evaluated the number of ALP+ colonies after the first passage. As shown in Figure 1C, reprogrammed BM mononuclear cells generated a much higher number of ALP+ colonies compared with fibroblasts in 2 independent experiments. BM iPSCs expressed the typical ESC markers OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, LIN28, SSEA3, SSEA4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, and ALP as determined by RT-PCR and flow cytometry (Figure 1E,J). We also observed up-regulation of other ESC signature genes REX1 (ZFP42), GDF3, DNMT3B, and TDGF1, which were not present in our reprogramming cocktails (Figure 1F,J). As expected, BM iPSCs lost expression of the pan-hematopoietic markers CD45 and CD43 (data not shown) and genes typically found in the BM hematopoietic cells (Figure 2C). To characterize the molecular properties of BM iPSCs, we performed a global analysis of the gene expression of blood-derived iPSCs and compared them with 5 hESC lines and 3 iPSCs derived from fibroblasts using plasmid combination 19 (DF19 iPSC lines).14 In this analysis, we also included 2 iPSC lines derived from fibroblasts using the same set of reprogramming factors but using expression vectors with different transgene arrangements (combination 6, DF6 iPSC lines).14 Global analysis of gene expression confirmed the similarity of BM iPSCs to 5 hESC and 5 fibroblast iPSC lines. As shown in Figure 2A, BM iPSCs clustered together with hESCs and fibroblast-derived iPSCs, but were distant from the parental BM cells. Similarly, analysis of scatter plots shows a much tighter correlation of reprogrammed BM cells with hESCs than with parental cells (Figure 2B). The pluripotency of iPSC-derived cell lines was confirmed using a teratoma-formation assay with demonstration of derivatives of all 3 germ layers (Figure 1G). Whereas we detected an abnormal karyotype in one BM iPSC line, the majority of them maintained the normal karyotype (Figure 1H).

Global analysis of gene expression in hESCs and iPSCs generated from BM, CB, and fibroblasts and their parental cells. (A) Pearson correlation analysis of global gene expression. (B) Scatter plots comparing the global gene-expression profiles of BM9 iPSC line with H9 hESCs (left) and parental BM cells (right). Pearson correlation coefficient (R) is shown in top left corner. The transcript expression levels are shown on a log2 scale. (C) Heat maps demonstrate the expression of hESC, fibroblast, and BM hematopoietic cell-enriched genes. Yellow lines outline major clusters shown in panel A.

Global analysis of gene expression in hESCs and iPSCs generated from BM, CB, and fibroblasts and their parental cells. (A) Pearson correlation analysis of global gene expression. (B) Scatter plots comparing the global gene-expression profiles of BM9 iPSC line with H9 hESCs (left) and parental BM cells (right). Pearson correlation coefficient (R) is shown in top left corner. The transcript expression levels are shown on a log2 scale. (C) Heat maps demonstrate the expression of hESC, fibroblast, and BM hematopoietic cell-enriched genes. Yellow lines outline major clusters shown in panel A.

Although we used single-cell subcloning to isolate cells that had lost episomal plasmids in our previous reprogramming studies,14 our initial subcloning experiments with BM iPSCs demonstrated that all clones obtained at passage 15 were transgene-free (Figure 1I). Based on these experiments, we concluded that episomal plasmids were cured from BM iPSCs faster than we had previously thought. To analyze the kinetics of episomal plasmid loss, we extracted episomal DNA at different passage from 10 random BM iPSC lines. We found that episomal DNA was lost progressively, and was absent in some samples as early as passage 3. By passage 7, we did not detect any transgene in 7 of 10 lines checked with multiple pairs of primers (Figure 1K).

We applied a similar approach to the reprogramming of mononuclear cells of CB. Although the efficiency of reprogramming was much lower, we were able to obtain 6 CB iPSCs from approximately 3 × 106 transfected CB mononuclear cells. By adding small-molecule thiazovivin21 to reprogramming cultures, we were able to increase the reprogramming efficiency of CB cells by more than 10 times (Figure 3B). We obtained a total of 22 CB iPSC lines from 2 reprogramming experiments. All CB iPSCs displayed the typical hESC phenotype and gene-expression profile (Figure 3A,G). Six selected CB iPSC lines showed pluripotency in the teratoma assay and were free of episomal vectors and genomic integration CB iPSCs (Figure 3E-F).

Reprogramming of CB mononuclear cells with nonintegrating constructs. (A) All 22 CB iPSC lines express hESC-specific surface markers as indicated, and express OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2. iPSC lines checked are: CB iPSC1 to CB iPSC6, CB iPSCT1 to CB iPSCT10, CB iPSCT12 to CB iPSCT16, and CB iPSCND. (B) Thiazovivin (T+) promotes reprogramming of CB mononuclear cells. The numbers of iPSC lines generated from 1.7 × 106 transfected CB mononuclear cells are shown. (C) Normal karyogram of the CB iPSC6 line. (D) H&E staining of representative terotoma from CB iPSCs with derivatives of 3 germ layers. (E-G) CB iPSCs cells are free of transgene and episomal DNA. Episomal DNA (E) and genomic DNA (F) were prepared from CB iPSC lines of CB iPSC1, CB iPSC6, and CB iPSCT3, -4, -7, -8, and -9. RT-PCR analysis of expression of transgenes and endogenous pluripotency genes. T-transgene–specific primers were used as indicated.

Reprogramming of CB mononuclear cells with nonintegrating constructs. (A) All 22 CB iPSC lines express hESC-specific surface markers as indicated, and express OCT4, NANOG, and SOX2. iPSC lines checked are: CB iPSC1 to CB iPSC6, CB iPSCT1 to CB iPSCT10, CB iPSCT12 to CB iPSCT16, and CB iPSCND. (B) Thiazovivin (T+) promotes reprogramming of CB mononuclear cells. The numbers of iPSC lines generated from 1.7 × 106 transfected CB mononuclear cells are shown. (C) Normal karyogram of the CB iPSC6 line. (D) H&E staining of representative terotoma from CB iPSCs with derivatives of 3 germ layers. (E-G) CB iPSCs cells are free of transgene and episomal DNA. Episomal DNA (E) and genomic DNA (F) were prepared from CB iPSC lines of CB iPSC1, CB iPSC6, and CB iPSCT3, -4, -7, -8, and -9. RT-PCR analysis of expression of transgenes and endogenous pluripotency genes. T-transgene–specific primers were used as indicated.

Hematopoietic differentiation potential of blood-derived iPSCs

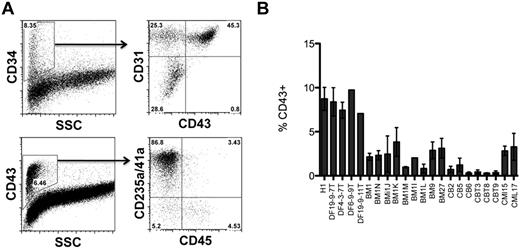

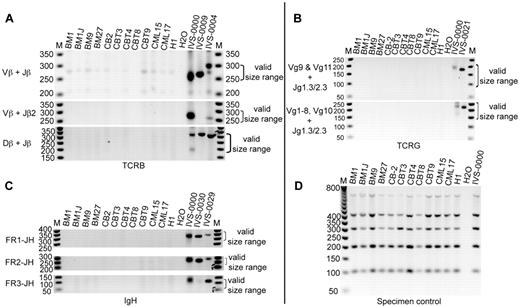

To test hematopoietic differentiation potential of blood-derived iPSCs, we used iPSC cocultured with OP9.22 As we showed previously, hematopoietic differentiation from hESCs proceeds through the formation of a population of CD34+ cells, which includes CD34+CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors, CD34+CD31+CD43− endothelial cells, and CD34+CD31−CD43− mesenchymal cells. The 3 major populations of CD43+ hematopoietic cells include CD235a/CD41a+ erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors and lin−CD43+CD45− and CD45+ multipotent progenitors.18 Earlier, we found that fibroblast-derived iPSCs and hESCs follow a very similar pattern of hematopoietic differentiation, although significant variation in blood-forming potential was observed between different iPSC clones. In addition, we noted that the generation of 4 iPSC clones was sufficient to ensure that at least one clone showed good hematopoietic differentiation potential.23 Testing of 4 BM iPSC lines revealed a similar differentiation pattern of BM iPSCs (Figure 4A). However, opposite our expectations, all 4 BM iPSCs produced fewer CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors than H1 hESCs or transgene-free fibroblast-derived iPSCs obtained using a similar method. Screening 5 additional BM iPSCs and 6 CB iPSCs failed to reveal a clone with higher differentiation potential, indicating that our blood-derived iPSCs were somewhat resistant to differentiating back to the blood in coculture with OP9 (Figure 4B). Because recent studies have suggested that lymphoid cell–derived iPSCs differentiate into blood less efficiently than CD34+ cell–derived iPSCs,7 we evaluated the rearrangement of TCR and IGH genes in our cells to determine whether our iPSCs originated from lymphoid cells. As shown in Figure 5, all 9 tested iPSC lines lacked rearrangements of TCR and IGH, indicating that their origin was non–B- or non–T-lymphoid cells.

Hematopoietic differentiation potential of BM- and CB-derived iPSCs. (A) In coculture with OP9, blood-derived iPSCs generate a CD34+ population of cells with typical subsets including CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors, CD31+CD43− endothelial cells, and CD31−CD43− mesenchymal cells. The CD43+ population of hematopoietic cells consists of CD235a+CD41a+/− erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors and CD235a/CD41a−CD45+/− multipotent progenitors. The representative experiment shows hematopoietic subsets generated from the BM iPSC1 line. (B) Percentage of CD43+ hematopoietic cells generated from hESC H1, fibroblast (DF), and blood-derived (BM, CB) iPSC lines after 8 days of coculture with OP9.

Hematopoietic differentiation potential of BM- and CB-derived iPSCs. (A) In coculture with OP9, blood-derived iPSCs generate a CD34+ population of cells with typical subsets including CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors, CD31+CD43− endothelial cells, and CD31−CD43− mesenchymal cells. The CD43+ population of hematopoietic cells consists of CD235a+CD41a+/− erythro-megakaryocytic progenitors and CD235a/CD41a−CD45+/− multipotent progenitors. The representative experiment shows hematopoietic subsets generated from the BM iPSC1 line. (B) Percentage of CD43+ hematopoietic cells generated from hESC H1, fibroblast (DF), and blood-derived (BM, CB) iPSC lines after 8 days of coculture with OP9.

Analyses of TCR and IGH rearrangement in BM and CB iPSC lines. (A) PCR analyses of TCRB rearrangements. (B) PCR analyses of TCRG rearrangement. (C) PCR analyses of IGH rearrangements. FR indicates framework. (D) Specimen controls. M indicates the 50-bp DNA ladder; H2O, no template control; H1, genomic DNA from hESC H1 (negative control). Eleven iPSC lines were examined as indicated. IVS-0000 is a polyclonal control DNA; IVS-0009, IVS-0004, IVS-0021, IVS-0030, and IVS-0029 are clonal control DNAs.

Analyses of TCR and IGH rearrangement in BM and CB iPSC lines. (A) PCR analyses of TCRB rearrangements. (B) PCR analyses of TCRG rearrangement. (C) PCR analyses of IGH rearrangements. FR indicates framework. (D) Specimen controls. M indicates the 50-bp DNA ladder; H2O, no template control; H1, genomic DNA from hESC H1 (negative control). Eleven iPSC lines were examined as indicated. IVS-0000 is a polyclonal control DNA; IVS-0009, IVS-0004, IVS-0021, IVS-0030, and IVS-0029 are clonal control DNAs.

Reprogramming of BM samples with CML

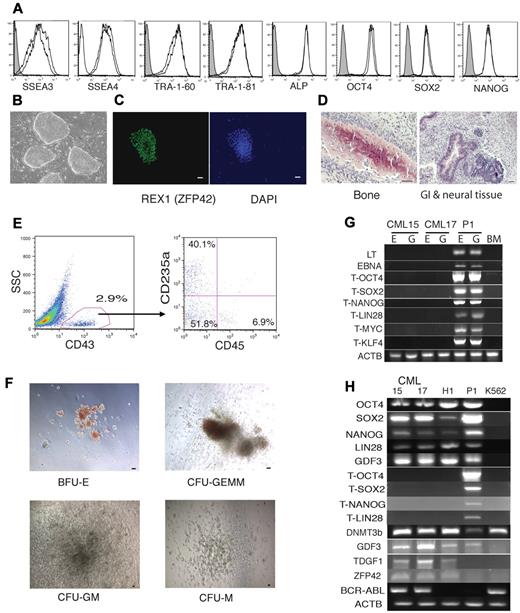

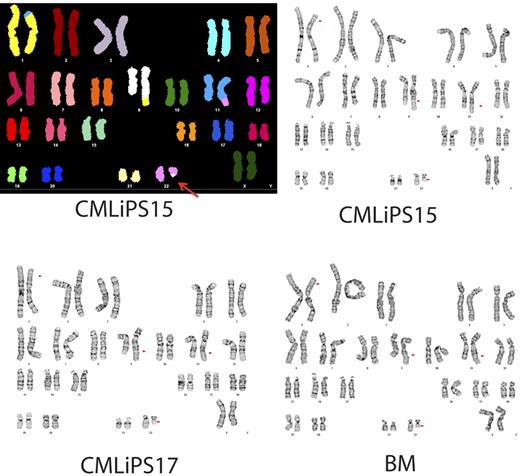

Reprogramming of neoplastic BM cells provides an opportunity to address the effect of oncogenes and patient-specific chromosomal abnormalities on the development of the leukemia phenotype in vitro. However the virus-based approach for reprogramming leukemic cells is highly undesirable because of genomic integration and background expression of reprogramming factors, some of which are oncogenes. Therefore, we applied episomal vectors to generate transgene-free iPSCs from a patient with CML in the chronic phase. We picked, expanded, and froze 50 CML iPSC lines from a single reprogramming. As with normal BM, we were able to generate multiple transgene-free CML iPSC lines with typical features of pluripotent stem cells. Two transgene-free CML iPSC lines were selected and characterized (Figure 6). RT-PCR analysis revealed that both CML iPSCs retained typical BCR-ABL fusion (Figure 6H). Moreover, the CML iPSCs were found to have a complex karyotype with a 4-way translocation between chromosomes 1, 9, 22, and 11 that was present in the patient BM (Figure 7). CML iPSC lines lacked rearrangement of TCR or IGH, indicating derivation from nonlymphoid cells (Figure 5). After hematopoietic differentiation, these cell lines generated CD43+ hematopoietic progenitors, which included typical subsets of CD235a/CD41a+ erythro-megakaryocytic and lin−CD34+CD43+CD45+/− multipotent progenitors (Figure 6E). In a colony-forming assay, these differentiated CML iPSCs formed all types of hematopoietic colonies, including granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, megakaryocyte and giant granulocyte-macrophage colonies (Figure 6F).

Generation of iPSCs from BM samples from a patient in the chronic phase of CML. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of hESC-specific marker expression in CML iPSC15 and CML iPSC17. (B) Bright-field image demonstrating typical hESC morphology of CML iPSCs growing on MEFs. (C) Representative immunofluorescent staining of CML iPSCs with REX1 antibody. Bar indicates 50 μm. (D) Representative H&E staining of teratoma generated from CMLiPS15 showing derivatives of 3 germ layers as indicated in each of the panels. (E) Flow cytometric demonstration of differentiation of CMLiPS15 into blood cells in OP9 coculture. (F) Colony-forming unit assay from blood progenitor cells differentiated from line CML iPSC15. BFU-E indicates burst-forming unit-erythroid; CFU-GEMM; colony-forming unit-granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, and megakaryocyte; CFU-M, colony-forming unit-macrophage; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit-granulocyte and monocyte. (G) CML iPSC lines 15 and 17 are free of transgene and vector sequence; E indicates the episomal fraction and G the genomic fraction of DNA; BM, human BM genomic DNA; P1, human BM mononuclear cells transfected with identical constructs. The T series of primers are transgene specific. ACTB indicates human actin primers that were used to check the DNA quality. (H) CML iPSCs express pluripotent genes, but not the corresponding transgenes. P1 indicates human BM mononuclear cells transfected with identical constructs. The hESC line H1 is the positive control and the Philadelphia chromosome-positive line K562 is used as the negative control for pluripotency, but as a positive control for the BCR-ABL fusion gene.

Generation of iPSCs from BM samples from a patient in the chronic phase of CML. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of hESC-specific marker expression in CML iPSC15 and CML iPSC17. (B) Bright-field image demonstrating typical hESC morphology of CML iPSCs growing on MEFs. (C) Representative immunofluorescent staining of CML iPSCs with REX1 antibody. Bar indicates 50 μm. (D) Representative H&E staining of teratoma generated from CMLiPS15 showing derivatives of 3 germ layers as indicated in each of the panels. (E) Flow cytometric demonstration of differentiation of CMLiPS15 into blood cells in OP9 coculture. (F) Colony-forming unit assay from blood progenitor cells differentiated from line CML iPSC15. BFU-E indicates burst-forming unit-erythroid; CFU-GEMM; colony-forming unit-granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, and megakaryocyte; CFU-M, colony-forming unit-macrophage; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit-granulocyte and monocyte. (G) CML iPSC lines 15 and 17 are free of transgene and vector sequence; E indicates the episomal fraction and G the genomic fraction of DNA; BM, human BM genomic DNA; P1, human BM mononuclear cells transfected with identical constructs. The T series of primers are transgene specific. ACTB indicates human actin primers that were used to check the DNA quality. (H) CML iPSCs express pluripotent genes, but not the corresponding transgenes. P1 indicates human BM mononuclear cells transfected with identical constructs. The hESC line H1 is the positive control and the Philadelphia chromosome-positive line K562 is used as the negative control for pluripotency, but as a positive control for the BCR-ABL fusion gene.

Karyograms of BM cells from a patient with CML and the 2 iPSCs derived from these cells. Top left panel shows spectral karyogram of CML iPSC15. SKY analysis demonstrates the 4-way translocation between chromosomes 1, 9, 11, and 22, shown here by classification-colored metaphase chromosomes. Translocations are apparent by the different colors of translocated segments representing the chromosome of origin. The Philadelphia chromosome is indicated by the red arrow. Standard G-banded karyotyping (top right and bottom panels) shows the complex 4-way translocation t(1;9;22;11)(p34.1;q34;q11.2;q23) found in all cells examined from the BM and from both iPSC lines (CML iPSC). The translocation 9;22 breakpoints of the BCR/ABL fusion are embedded in this rearrangement.

Karyograms of BM cells from a patient with CML and the 2 iPSCs derived from these cells. Top left panel shows spectral karyogram of CML iPSC15. SKY analysis demonstrates the 4-way translocation between chromosomes 1, 9, 11, and 22, shown here by classification-colored metaphase chromosomes. Translocations are apparent by the different colors of translocated segments representing the chromosome of origin. The Philadelphia chromosome is indicated by the red arrow. Standard G-banded karyotyping (top right and bottom panels) shows the complex 4-way translocation t(1;9;22;11)(p34.1;q34;q11.2;q23) found in all cells examined from the BM and from both iPSC lines (CML iPSC). The translocation 9;22 breakpoints of the BCR/ABL fusion are embedded in this rearrangement.

Discussion

Current methods for blood reprogramming rely on use of genome-integrating viruses and require several rounds of viral infection. Our data show that iPSC lines free of any transgene or vector sequence could be obtained using EBV-based episomal vectors. The efficiency of reprogramming blood cells by this method was at least 100 times higher than that of fibroblasts and was similar or higher to reported reprogramming efficiency using virus-based methods. Although previous studies have demonstrated the generation of iPSCs from blood using CD34+ cells3,4 or T cells,5-7 these methods require the isolation of progenitors or mature blood cells before reprogramming. We demonstrated that successful reprogramming could be achieved using just 106-107 mononuclear cells from CB or BM without any additional purification steps. Moreover, iPSCs with rearranged TCR or IGH may be undesirable for potential therapeutic applications and modeling of lymphoid development, because prearranged antigen-receptor genes are expressed precociously in early hematopoietic progenitors, leading to abnormal hematopoietic and lymphoid development and predisposition for lymphomas.24 A selective reprogramming of nonlymphoid cells using our method makes it possible to obtain iPSCs lacking TCR and IGH rearrangements using nonseparated mononuclear cells. Reprogramming of blood cells with episomal vectors occurs more rapidly than fibroblasts and is associated with a loss of episomal DNA in the majority of iPSC lines after 7 passages, thus eliminating the requirement for extensive additional subcloning steps. Human BM and CB represent the most accessible sources of somatic cells, with extensive and diverse archived samples available. Successful reprogramming of frozen blood samples containing less than 107 mononuclear cells in the present study clearly demonstrates the applicability of the described method for the generation of transgene-free iPSCs without rearranged antigen-receptor genes from archived samples of normal and diseased blood cells for studies of hematopoietic development, blood disease pathogenesis, and drug screening, and potentially for therapeutic purposes.

Although somatic cell reprogramming is associated with almost complete resetting of the epigenetic and gene-expression profiles to an ESC state,25 a recent report strongly suggests that blood-derived iPSCs retain epigenetic memory of their origin and differentiate back into the blood with efficiency higher compared with fibroblast-derived iPSCs.26 However, extensive testing of BM and CB iPSCs generated in our studies revealed that all 15 blood-derived iPSCs produced noticeably lower numbers of CD43+ blood cells compared with fibroblast-derived iPSCs. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear. Because different iPSC lines require different concentrations of differentiation factors for optimal induction of the desired population of cells,27 it is possible that the balance of hematopoiesis-inductive factors in the OP9 system is less optimal for blood-derived iPSCs compared with fibroblast derived iPSCs. In contrast, the previously described embryoid body method supports hematopoiesis from ESCs and blood iPSCs, but not from fibroblast-derived iPSCs.26 Although we know that iPSCs generated by our method are derived from non–B- or non–T-lymphoid cells, the stage of maturation of cells that underwent reprogramming in our experiments is unknown. Because previous studies found that iPSCs obtained from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors give rise to blood cells more efficiently than iPSCs generated from terminally differentiated blood cells,7 it is possible that the low hematopoietic differentiation potential observed in our studies could be related to the reprogramming of more mature types of blood cells. Interestingly, a recent study found that B cell–derived iPSCs were resistant to differentiation back into B cell–lineage cells, but could be more easily differentiated into T cells,28 indicating that turning iPSCs back into parental cells could be more difficult. Because our iPSCs are derived most likely from cells of erythro-megakaryocytic or myelomonocytic lineages (nonlymphoid cells), we can speculate that the low hematopoietic differentiation potential of our cells could be explained by their resistance to differentiate back into parental cells—myeloid cells that constitute the predominant type of cells in iPSC hematopoietic differentiation cultures. It is also possible that slight differences exist in epigenetic remodeling and/or gene expression after reprogramming of blood cells with nonintegrating episomal and integrating lentiviral vectors. Because continued passaging of iPSCs equalizes their genomic DNA methylation signatures and differentiation potential,29 it will be important to determine whether the blood-forming potential of our iPSC lines will change at later passages.

Reprogramming neoplastic blood cells to pluripotency provides a novel tool with which we can explore the pathogenic mechanisms of tumor development and drug resistance using iPSCs with patient-specific chromosomal abnormalities. Recent studies have demonstrated successful generation of iPSCs from neoplastic blood cells from patients with the JAK2-V617F mutation4 and from a KBM7 cell line derived from the blast-crisis stage of CML30 using lentiviral vectors. As expected, the differentiated blood cells from these iPSCs show functional properties of neoplastic cells. As we showed previously, background expression of reprogramming factors can be detected even in terminally differentiated cells generated from transgenic iPSCs,23,31 and can affect the properties of differentiated cells.32 Such background expression of reprogramming factors, some of which are oncogenes, and genomic integration are highly undesirable for cancer studies. Our studies show the feasibility of obtaining transgene-free iPSCs from BM samples of blood cancer patients, and provide the first time demonstration of the successful generation of iPSCs from patients with CML. There are several major advantages to using iPSCs for studies of blood cancer pathogenesis. Using well-defined temporal windows and surface markers, distinct cell subsets with tumor-initiating potential after transplantation in immunodeficient mice could be identified. Such an approach makes it possible to address cancer stem-cell potential at stages of differentiation for which it may be difficult to obtain samples from the patient, for example, at the hemangioblast stage. In addition, this model gives a unique opportunity to explore the role of epigenetic changes in activation of oncogene-induced aberrant regulatory circuit. Because CML progression and acceleration are often associated with the appearance of a new chromosomal translocation in addition to a Philadelphia chromosome, iPSCs generated from blood cells obtained from the same patient at different stages of disease would be a valuable tool for addressing molecular mechanisms of CML progression and drug resistance.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Toru Nakano for providing OP9 cells and Krista Eastman and Joan Larson for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by funds from the National Institutes of Health (grants P01 GM081629, R01 HL081962, and P51RR000167) and from the Charlotte Geyer Foundation. K.S. is supported by funds from the Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand.

National Institutes of Health

Authorship

Contribution: K.H. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; J.Y. designed experiments and generated reprogramming vectors; K.S. and K.-D.C. performed differentiation studies; S.T and R.S. performed bioinformatic analysis of microarray data; K.M. performed karyotyping; J.A.T. conceived of and designed the experiments; and I.I.S. supervised the project, designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.A.T. is a founder, stock owner, consultant, and board member of Cellular Dynamics International (CDI). He also serves as scientific advisor to and has financial interests in Tactics II Stem Cell Ventures. I.I.S. is a founder, stock owner, and consultant for Cellular Dynamics International. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dr Igor I. Slukvin, Dept of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Wisconsin National Primate Research Center, University of Wisconsin, 1220 Capitol Ct, Madison, WI 53715; e-mail: islukvin@wisc.edu.