Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells play a major role in immunologic surveillance of cancer. Whether NK-cell subsets have specific roles during antitumor responses and what the signals are that drive their terminal maturation remain unclear. Using an in vivo model of tumor immunity, we show here that CD11bhiCD27low NK cells migrate to the tumor site to reject major histocompatibility complex class I negative tumors, a response that is severely impaired in Txb21−/− mice. The phenotypical analysis of Txb21-deficient mice shows that, in the absence of Txb21, NK-cell differentiation is arrested specifically at the CD11bhiCD27hi stage, resulting in the complete absence of terminally differentiated CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. Adoptive transfer experiments and radiation bone marrow chimera reveal that a Txb21+/+ environment rescues the CD11bhiCD27hi to CD11bhiCD27low transition of Txb21−/− NK cells. Furthermore, in vivo depletion of myeloid cells and in vitro coculture experiments demonstrate that spleen monocytes mediate the terminal differentiation of peripheral NK cells in a Txb21- and IL-15Rα–dependent manner. Together, these data reveal a novel, unrecognized role for Txb21 expression in monocytes in promoting NK-cell development and help appreciate how various NK-cell subsets are generated and participate in antitumor immunity.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are innate lymphocytes that participate in the regulation of immune responses and in immunologic surveillance of cancer.1 NK cells develop mainly in the bone marrow (BM) and are distributed throughout the body in both lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues.2 It is unclear, however, whether this wide distribution is the result of their recirculation, the existence of NK subsets with different homing capacities, or their development at multiples sites.

Surface markers and gene expression profiles have been used to define various NK-cell subpopulations. Based on the expression of the integrin CD11b and the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily molecule CD27, mature murine NK cells have been classified into distinct populations.3 The precursor/product relationship between these subsets has been investigated using a number of approaches to conclude that CD11blowCD27low, CD11blowCD27hi, CD11bhiCD27hi, and CD11bhiCD27low represent discrete and sequential stages of in vivo maturation following the pathway double-negative to CD11blowCD27hi to double-positive to CD11bhiCD27low.4 Functional features of CD11bhiCD27hi and CD11bhiCD27low NK cells have been studied mostly in vitro. For example, CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells responded to either IL-12 or IL-18, key cytokines derived from antigen-presenting cells, by rapidly producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ), whereas CD11bhiCD27low NK cells produced IFN-γ only when stimulated with a combination of IL-12 and IL-18. Furthermore, CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells showed greater responsiveness to dendritic cells (DCs), producing higher amounts of IFN-γ on in vitro coculture with BM-derived DCs, compared with CD11bhiCD27low cells.3 Whether NK-cell subsets have specific roles during immune responses and what the signals are driving the final stages of differentiation remain unknown.

T-bet is a tyrosine and serine phosphorylated protein belonging to the T-box family specifically expressed in the hematopoietic cell compartment.5 T-bet is responsible for direct transactivation of the IFN-γ gene on CD4 Th1 T cells6 and specifies a transcriptional program that imprints homing of T cells to proinflammatory sites.7 T-bet is also expressed in NK cells, where it plays a role in maturation and homeostasis.8 Functionally, Txb21−/− NK cells exhibit a small decrease in prototypic target cell killing, consistent with a modest decrease in IFN-γ, perforin, and granzyme B.8 It remains to be established whether the phenotype, function, and anatomic distribution of NK-cell subsets is modulated by T-bet and whether extrinsic signals complement the defective NK-cell development reported in Txb21-deficient mice.

In the past few years, relevant interactions occurring between NK cells and cells of the monocyte/macrophage/DC lineages have been extensively investigated. In vitro studies have shown that the NK-cell crosstalk with DC results in activation of both NK cells and DCs.9-11 In addition, the transient in vivo depletion of DCs results in lack of homeostatic proliferation of NK cells in lymphopenic conditions, which is mediated by DC-derived IL-15.12 Functional interactions between NK cells and DCs during viral infections have also been highlighted. For example, the presence of Ly49H+ NK cells is required to retain CD8α+ DCs in the spleen, whereas CD8α+ DCs are required for the expansion of Ly49H+ NK cells that occurs at the late stage of acute viral infection.13 Moreover, NK cells limit viral-induced immunopathology by eliminating activated macrophages of the spleen,14 and mutual activation of NK cells and monocytes contribute to the initiation and maintenance of immune responses at sites of inflammation.15 Whether myeloid cells mediate NK-cell differentiation in peripheral lymphoid organs and whether the expression of T-bet in monocyte/macrophage/DC plays any role in these events remain largely unknown.

In this study, we show that CD11bhiCD27low NK cells are critically involved in the rejection of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-negative tumors. The observation that this response is severely impaired in Txb21−/− mice that completely lack CD11bhiCD27low NK cells prompted us to investigate the signals involved in the terminal differentiation of NK cells. We demonstrate that the CD11bhiCD27hi to CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell transition depends on the interaction of NK cells with spleen monocytes. Mechanistically, we find that the expression of Txb21 and IL-15Rα on monocytes is determinant to allow NK cells to proceed to the final stage of differentiation. Thus, our work dissects critical steps in peripheral NK-cell differentiation and demonstrates that the interaction between NK cells and monocytes could be relevant in antitumor immunity.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice were purchased from Harlan-United Kingdom. C57BL/6 and BALB/c Txb21−/− mice were purchased from Taconic Farms. The CD11c-DTR mice carry a transgene encoding the simian DT receptor (DTR)-gfp fusion protein under control of the murine CD11c promoter.16 Transgenic mice designed for inducible depletion of CSF-1 receptor (CD115) expressing cells (MaFIA) have been described.17 The transgene in MaFIA mice is under control of the c-fms promoter that regulates expression of the CSF-1 receptor. These mice express eGFP and a membrane-bound suicide protein composing the human low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor, the FK506 binding protein, and the cytoplasmic domain of Fas. AP20187 is a covalently linked dimer (Ariad Pharmaceuticals) that cross-links the FK506 binding protein region of the suicide protein and induces caspase 8–dependent apoptosis as described.17 CD11c-DTR and MaFIA mice were originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice were bred and maintained under sterile conditions in the Biologic Services Unit (New Hunts House) of King's College London. Mouse handling and experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with national and institutional guidelines for animal care and use.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were stained with the following antibodies: Pacific Blue–, or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–labeled (2C11); AlexaFluor-700–, FITC-, or phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD11b (M1/70); phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD27 (LG.3A10); FITC-labeled anti-Ly6G (1A8); FITC-labeled anti-IAb (AF6-120.1); FITC-labeled CD19 (1D3); biotinylated KLRG-1 (2F1); and FITC-labeled CD11c (HL3) from BD Biosciences; polyclonal goat anti–IL-15Rα, from R&D Systems; Alexa647- and FITC-labeled anti-NKp46 (29A1.4); phycoerythrin-labeled anti-CD115 (AFS98); and Alexa647-labeled anti–T-bet (4B10) from eBioscience. All samples were analyzed on a FACS-LSRII or sorted in a FACSAria (both BD Biosciences).

Short-term in vivo NK-cell differentiation assay

Txb21−/− spleen cells were labeled with 2.5μM 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester (CFSE, Invitrogen), and 25 × 106 cells were injected intravenously into Txb21+/+ or Txb21−/− mice. The expression of CD27 and CD11b in NKp46+CD3− NK cells was evaluated 48 hours after transfer.

BM chimera

Recipient mice were irradiated with 600 cGy 8 and 4 hours before the procedure. BM cells were harvested aseptically from the tibia and femurs of donor Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− mice, and 2 × 106 cells each were coinjected intravenously in the recipients. Irradiated mice were maintained on trimethaprim-sulphamethoxazole–treated water in sterile cages for 6 weeks before analysis.

In vivo modulation of myeloid cell numbers

For depletion of myeloid cells, 2 alternative approaches were used. First, 250 μL of clodronate-loaded liposomes was injected intravenously into C57BL/6 mice. Clodronate was a gift from Roche and was incorporated into liposomes as previously described.18 The doses used fully eliminate blood monocytes19 and splenic and liver macrophages.18 Second, CD115 MaFIA mice were injected with dimerizer AP20187, a gift from Ariad Pharmaceuticals. Lyophilized AP20187 was dissolved in 100% ethanol at a concentration of 13.75 mg/mL (1nM) stock solution and stored at −20°C. MaFIA mice received 0.55 mg/mL of AP20187 containing 4% ethanol, 10% PEG-400, and 1.7% Tween-20 in water. A total of 10 mg/kg AP20187 was administered intraperitoneally on days −4, −3, −2, and −1, and spleens were harvested and labeled as indicated 24 hours after the last injection. For monocyte and macrophage expansion, mice were injected with 10 μg CSF-1 for 5 consecutive days; mice were killed 24 hours after last injection.

NK-cell and monocyte coculture

Spleen NK cells were negatively enriched by an NK-cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of the sorted population was typically more than 90% DX5+ cells. In some experiments, spleen NKp46+CD3−CD27+Txb21−/− NK cells were sorted using FACSAria. The purity of the sorted population was more than 98%. Monocytes were enriched with the StemCell kit and identified as CD11b+ to a more than 95% purity (supplemental Figure 4C, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article). In some experiments, mouse monocytes were identified as Lin− CD11b+ and sorted with a FACSAria to a purity of more than 99%. Lineage cocktail contained anti-CD3/CD19/NKp46/MHC class II/CD11c/Ly6G (supplemental Figure 4D). NKp46+CD3−CD27+Txb21−/− NK cells, and monocytes were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio (1 × 105 each) in round-bottom 96-well plates in the presence of 100 ng/mL of mouse IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-15 cytokines or IL-15/IL15Rα complexes (R&D Systems). In some experiments, interaction between IL-15 and IL-15Rα was prevented by adding 5 μg/mL of anti-IL15Rα antibodies (R&D Systems) into cocultures. Human IL-15 (R&D Systems) was precomplexed with murine IL-15Rα-human IgG1-Fc fusion protein (R&D Systems) as described20 and incubated at 1 μg/106 cells with Txb21−/− monocytes.

Immunofluorescence on tissue sections

Immunofluorescence was performed on 7-μm-thick serial frozen sections. Sections were fixed with acetone, saturated in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% (volume/volume) Triton-X and 10% (volume/volume) donkey serum before staining with rat anti–mouse-CD115 (AFS98; eBioscience), purified polyclonal goat anti–mouse NKp46 (R&D Systems), and anti–CD3-APC (2C11; BD Biosciences), followed by secondary donkey anti–goat IgG–Alexa-488 (Invitrogen) and donkey anti–rat DLR546 (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After staining, slides were dried and mounted with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) and examined with an LSM 510 confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM Exciter). Pictures were acquired using Zen and LSM image browser software (Carl Zeiss).

Tumor clearance in vivo

Live tumor cells (2 × 105 RMA and 2 × 105 RMA-S) were labeled with 5μM 5,6-(4-chloromethyl)-benzoyl-1-amino-tetramethylrhodamine (CMTMR, Invitrogen) or 2.5μM CFSE, respectively, and injected intraperitoneally in a volume of 0.2 mL. Forty-eight hours later, peritoneal cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry for CMTMR and CFSE detection. In some experiments, tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously with 5 × 106 of highly purified Txb21+/+ or 5 × 106Txb21−/− spleen NK cells. NK-cell depletion was achieved by injecting 200 μg intraperitoneally of anti-NK1.1 antibodies or isotype as controls, 2 days before tumor challenge.

Statistical analysis

Data, presented as mean ± SD, were analyzed with a paired Student t test using the SPSS software Version 17. P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Defective NK-cell development in Txb21−/− mice is rescued by a Txb21+/+ environment

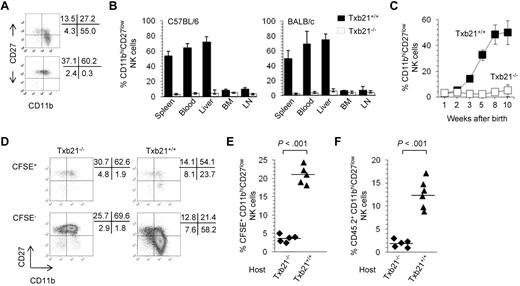

Previous studies have shown that T-bet regulates differentiation and peripheral homeostasis of NK cells.8 However, whether T-bet identifies checkpoints during NK-cell development in peripheral organs is unknown. To address this issue, we analyzed the expression of CD11b and CD27 in the NK cells of Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− mice. Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 1 show striking differences in the overall distribution of NK-cell subsets in 8- to 10-week-old Txb21−/− mice compared with Txb21+/+ mice. Indeed, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells are virtually absent from the spleen of Txb21−/− mice. Furthermore, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells could not be detected in the blood and in any other lymphoid organ tested both in C57BL/6 and BALB/c backgrounds (Figure 1B). It has been reported that the proportion of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells increases with age.21 To evaluate the role of T-bet in the ontogenetic appearance of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells, we next compared the development of NK cells in the spleen of Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− mice. We observed a gradual increase in the percentage of spleen CD11bhiCD27lowTxb21+/+ NK cells to reach a plateau at 8 weeks of age, with significant changes between 2 and 3, 4 and 5, and 5 and 8 weeks (Figure 1C). In sharp contrast, terminally differentiated CD11bhiCD27lowTxb21−/− NK cells were never detected in the spleen (Figure 1C) and in any other organ tested (not shown), at any time point studied up to 2 months after birth.

CD11bhiCD27low NK cells are absent in Txb21−/− mice but can be rescued in a Txb21+/+ environment. (A) Expression of CD11b and CD27 in spleen NKp46+CD3− NK cells of Txb21+/+ (top panel) and Txb21−/− (bottom panel) C57BL/6 mice. (B) Frequency (mean ± SD) of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells of 6 mice per genotype in the indicated organs. (C) Frequency (mean ± SD) of CD11bhiCD27low NK cell of Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− C57BL/6 mice prepared from spleen of 5 mice per genotype at the ages indicated. (D) Txb21−/− spleen cells were labeled with CFSE and injected intravenously into Txb21−/− or Txb21+/+ hosts. Shown is the expression of CD11b and CD27 in the transferred CFSE+ (top panels) and host CFSE− (bottom panels) NKp46+CD3− NK cells in Txb21−/− (left panels) and Txb21+/+ (right panels) hosts. (E) Frequency of CFSE+ CD11bhiCD27low NK cells in 5 Txb21−/− and 5 Txb21+/+ mice. (F) Six Txb21+/+ and 5 Txb21−/− CD45.1 host mice were irradiated and transferred with Txb21−/− CD45.2 BM cells. Shown is the frequency of donor CD45.2 CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. (E-F) Bars represent the means within the groups.

CD11bhiCD27low NK cells are absent in Txb21−/− mice but can be rescued in a Txb21+/+ environment. (A) Expression of CD11b and CD27 in spleen NKp46+CD3− NK cells of Txb21+/+ (top panel) and Txb21−/− (bottom panel) C57BL/6 mice. (B) Frequency (mean ± SD) of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells of 6 mice per genotype in the indicated organs. (C) Frequency (mean ± SD) of CD11bhiCD27low NK cell of Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− C57BL/6 mice prepared from spleen of 5 mice per genotype at the ages indicated. (D) Txb21−/− spleen cells were labeled with CFSE and injected intravenously into Txb21−/− or Txb21+/+ hosts. Shown is the expression of CD11b and CD27 in the transferred CFSE+ (top panels) and host CFSE− (bottom panels) NKp46+CD3− NK cells in Txb21−/− (left panels) and Txb21+/+ (right panels) hosts. (E) Frequency of CFSE+ CD11bhiCD27low NK cells in 5 Txb21−/− and 5 Txb21+/+ mice. (F) Six Txb21+/+ and 5 Txb21−/− CD45.1 host mice were irradiated and transferred with Txb21−/− CD45.2 BM cells. Shown is the frequency of donor CD45.2 CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. (E-F) Bars represent the means within the groups.

Because T-bet is expressed in cells of the myeloid and lymphoid lineages,5 we next assessed the role of NK cell–extrinsic Txb21 in the generation of the CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell subset. We first used a short term in vivo differentiation assay, where CFSE-labeled Txb21−/− spleen cells were adoptively transferred into Txb21+/+ or Txb21−/− mice, to evaluate the appearance of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells in the spleen of the host. Figure 1D-E shows that, 2 days after transfer, Txb21−/− CD11bhiCD27low NK cells can be readily detected in the spleen of Txb21-sufficient recipients, but not in Txb21-deficient recipients. We also performed competitive BM chimera experiments where lethally irradiated Txb21+/+ hosts were reconstituted with a 1:1 mixture of Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− BM cells and confirmed that CD11bhiCD27lowTxb21−/− NK cells can be detected in the blood and spleen of Txb21+/+, but not Txb21−/−, hosts 6 weeks after BM reconstitution (Figure 1F). Together, these data demonstrate that the NK-cell differentiation program has a checkpoint between CD11bhiCD27hi and CD11bhiCD27low stages that cannot be completed in the absence of T-bet and that environmental signals contribute to terminal NK-cell development.

Spleen monocytes promote NK-cell differentiation in a T-bet-dependent manner

The complex process of NK-cell differentiation occurs at several distinct tissue sites, including the BM, liver, thymus,2 and lymph nodes and tonsils.22 However, very little is known about the cellular mechanisms leading to the formation of distinct NK-cell subsets. To identify the cellular components and anatomic distribution that limit NK-cell differentiation in Txb21−/− mice, we adoptively transfer CFSE-labeled Txb21−/− cells into splenectomized mice (supplemental Figure 2A). The absence of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells in the blood of splenectomized mice strongly suggests that CD27hi to CD27low transition may occur in the spleen.

Next, we sought to identify the T-bet-expressing cells that contribute to NK-cell differentiation. T-bet is expressed on γc-dependent lymphocytes, such as conventional T cells, NKT cells, NK cells, γδT cells, and B cells5 and on CD11c+ DCs.23 We hypothesized that the deletion of the cell component involved in NK CD27hi to CD27low step should result in changes in the overall distribution of NK-cell subsets in the spleen. Therefore, we used genetic models to investigate whether γc-dependent lymphocytes and DCs were involved in promoting NK-cell differentiation. We observed that the transition from CD27hi to CD27low stage readily occurs when Txb21−/− NK cells were transferred into Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−Txb21+/+ mice (supplemental Figure 2B). Furthermore, the administration of diphtheria toxin, which induces a transient depletion of DCs in CD11c-DTR-gfp mice,16 did not modify the spleen NK-cell subset composition (supplemental Figure 2C). These data indicate that DCs and γc-dependent lymphocytes are not required for NK terminal differentiation.

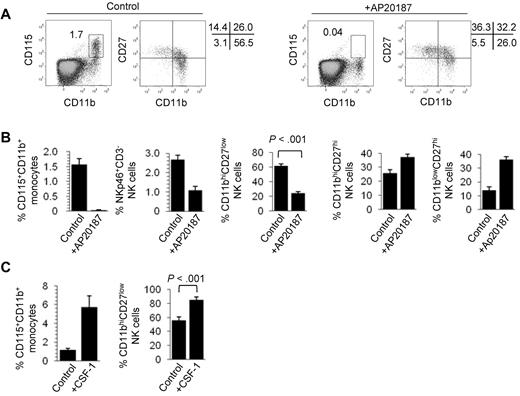

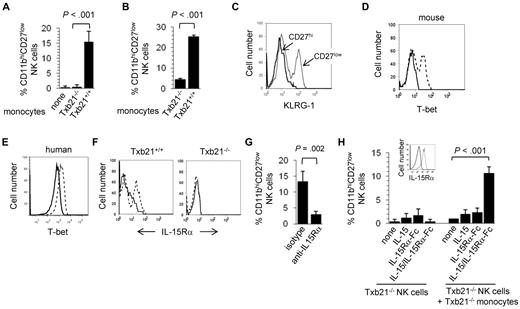

The red pulp of the spleen is a natural reservoir of mouse monocytes24 and the niche where splenic NK cells reside in the steady state.25 Because monocytes,6 but not macrophages,23 express T-bet, we next tested whether monocytes modulate NK-cell differentiation. To deplete in vivo mouse monocytes, we used 2 approaches. First, we analyzed the phenotype of splenic NK cells in MaFIA mice where transient elimination of CSF-1 receptor (CD115)-expressing cells is induced by administration of AP20187 dimerizer. Figure 2A shows that the complete elimination of CD115+CD11b+ monocytes in AP20287-treated mice correlates with a strong reduction in the proportion of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. Although the overall proportion of NK cells was reduced in AP20187-treated MaFIA mice, the frequency of CD11bhiCD27hi and CD11blowCD27hi increased in treated animals (Figure 2B). This, together with the fact that AP20187 does not modify the NK-cell subset composition in wild-type animals (supplemental Figure 3A), rules out nonspecific toxic effects of this compound. Second, we injected intravenously clodronate-loaded liposomes into wild-type C57BL/6 mice. This treatment resulted in the depletion of spleen monocytes (supplemental Figure 3B) and was accompanied by a strong reduction in the percentage of CD11bhiCD27low spleen NK cells (supplemental Figure 3C). Clodronate-loaded liposome treatment did not affect the overall frequency of conventional T cells (supplemental Figure 3C) or CD19+CD3− B cells (not shown). To further demonstrate the role for CD115+ cells in NK-cell differentiation, we used a complementary approach that consists of expanding in vivo the number of monocytes and investigating the overall distribution of NK-cell subsets in the spleen. Figure 2C shows that administration of CSF-1 (M-CSF), the ligand for the CSF-R, into wild-type results in a marked increase of CD115+CD11b+ monocytes in the spleen, which is accompanied by a significant expansion of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. Together, these experiments suggest that the presence of spleen CD11bhiCD27low NK cells correlates with that of CD115+ monocytes but does not clarify whether monocytes are involved in NK-cell survival or differentiation. To address this point, we next set up short-term cultures where monocytes were enriched from Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− mice (supplemental Figure 4) and were cocultured with sorted double-negative (CD11blowCD27hi) plus double-positive (CD11bhiCD27hi) NK cells. Remarkably, Txb21+/+, but not Txb21−/−, monocytes promoted the differentiation of Txb21−/− (Figure 3A) and Txb21+/+ (Figure 3B) CD11bhiCD27hi to CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. For Txb21−/− NK cells, CD27 loss was accompanied by the up-regulation of the killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG-1; Figure 3C), a surface molecule that is up-regulated on maturation and is selectively expressed by CD11bhiCD27low but not CD27hi or double-negative NK cells. To further support the notion that physiologically relevant cross-talk occurs between monocytes and NK cells in vivo, we performed immunohistologic studies to show that monocytes and NK cells are found in close proximity in the red pulp of the spleen (supplemental Figure 5).

Monocytes control CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell numbers. (A) Frequency of CD115+CD11b+ monocyte and expression of CD11b and CD27 in NKp46+CD3− NK cells in the spleen of control (left panels) and AP20187-treated (right panels) MaFIA mice. (B) Mean frequency ± SD of spleen CD115+CD11b+ monocytes, NKp46+CD3− NK cells, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells, CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells, and CD11blowCD27hi NK cells, of 3 experiments with 4 mice per experiment. (C) CD115+CD11b+ monocyte and of CD11b+CD27low NK-cell frequency in the spleen of control C57BL/6 mice or mice injected with CSF-1. Data are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments with 3 mice per group.

Monocytes control CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell numbers. (A) Frequency of CD115+CD11b+ monocyte and expression of CD11b and CD27 in NKp46+CD3− NK cells in the spleen of control (left panels) and AP20187-treated (right panels) MaFIA mice. (B) Mean frequency ± SD of spleen CD115+CD11b+ monocytes, NKp46+CD3− NK cells, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells, CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells, and CD11blowCD27hi NK cells, of 3 experiments with 4 mice per experiment. (C) CD115+CD11b+ monocyte and of CD11b+CD27low NK-cell frequency in the spleen of control C57BL/6 mice or mice injected with CSF-1. Data are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments with 3 mice per group.

Mouse monocytes promote NK-cell differentiation. Mouse Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− monocytes were cocultured with Txb21−/− (A) or Txb21+/+ (B) NKp46+CD3−CD27+ NK cells, and the appearance of CD27− NK cells was evaluated 24 hours later. Shown is a representative experiment of 3. (C) KLRG-1 expression in Txb21−/− CD27hi (solid line) and CD27low (dotted line) NK cells cocultured with monocytes as in panel D. (D) Intracellular T-bet expression in enriched mouse monocytes cultured in the presence (dotted line) or the absence (solid line) of 100 ng/mL mouse IFN-γ. (E) Intracellular T-bet expression in CD14-enriched human peripheral blood mononuclear cell monocytes cultured in the presence (dotted line) or the absence (solid line) of 100 ng/mL human IFN-γ. (F) Surface expression of IL-15Rα (dotted lines) on mouse Txb21+/+ (left panel) and Txb21−/− (right panel) mouse monocytes enriched and cultured as before; solid lines indicate isotype controls. (G) Enriched mouse monocytes and Txb21−/− NK cells were cocultured as before in the presence of blocking anti-IL-15Rα antibodies or isotype as controls. Shown is the frequency (mean ± SD) of CD27low NK cells 24 hours after culture, of 3 independent experiments. (H) Txb21−/− NK cells were cultured with IL-15, IL-15Rα-Fc, or IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes, in the presence or the absence of Txb21−/− monocytes. In the latter, monocytes were preincubated with cytokines or complexes before coculture with NK cells. Shown is the frequency of CD27low NK cells 24 hours after culture. (Inset) The expression of IL-15Rα in the surface of Txb21−/− monoyctes that were preincubated with IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes (dotted line); solid line indicates the staining of monocytes preincubated with phosphate-buffered saline.

Mouse monocytes promote NK-cell differentiation. Mouse Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− monocytes were cocultured with Txb21−/− (A) or Txb21+/+ (B) NKp46+CD3−CD27+ NK cells, and the appearance of CD27− NK cells was evaluated 24 hours later. Shown is a representative experiment of 3. (C) KLRG-1 expression in Txb21−/− CD27hi (solid line) and CD27low (dotted line) NK cells cocultured with monocytes as in panel D. (D) Intracellular T-bet expression in enriched mouse monocytes cultured in the presence (dotted line) or the absence (solid line) of 100 ng/mL mouse IFN-γ. (E) Intracellular T-bet expression in CD14-enriched human peripheral blood mononuclear cell monocytes cultured in the presence (dotted line) or the absence (solid line) of 100 ng/mL human IFN-γ. (F) Surface expression of IL-15Rα (dotted lines) on mouse Txb21+/+ (left panel) and Txb21−/− (right panel) mouse monocytes enriched and cultured as before; solid lines indicate isotype controls. (G) Enriched mouse monocytes and Txb21−/− NK cells were cocultured as before in the presence of blocking anti-IL-15Rα antibodies or isotype as controls. Shown is the frequency (mean ± SD) of CD27low NK cells 24 hours after culture, of 3 independent experiments. (H) Txb21−/− NK cells were cultured with IL-15, IL-15Rα-Fc, or IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes, in the presence or the absence of Txb21−/− monocytes. In the latter, monocytes were preincubated with cytokines or complexes before coculture with NK cells. Shown is the frequency of CD27low NK cells 24 hours after culture. (Inset) The expression of IL-15Rα in the surface of Txb21−/− monoyctes that were preincubated with IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes (dotted line); solid line indicates the staining of monocytes preincubated with phosphate-buffered saline.

It has been proposed that T-bet influences the generation of type I immunity, not only by controlling Th1 lineage commitment in the adaptive immune system6 but also by a direct influence on the transcription of the IFN-γ gene in myeloid cells, including human monocytes.26 In turn, monocyte-derived IFN-γ stimulates activation of T-bet expression as a positive loop feedback to sustain IFN-γ production. We next confirmed that T-bet expression is inducibly expressed in monocytes freshly isolated from mouse spleens (Figure 3D) and in human CD14+ monocytes isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (Figure 3E) that were cultured in the presence of IFN-γ.

NK cells do not survive in environments where IL-15Rα or the cytokine IL-15 are missing.27 Furthermore, it is well documented that mice deficient in the γ-common chain (γc) of the IL-15R (CD132) lack NK cells.28 It has been suggested that IL-15 needs to be trans-presented (chaperoned to the IL-15R) and exposed in the cell surface to modulate NK-cell survival.27 Relevant to our study, IL-15Rα is expressed on myeloid cells, including DCs and macrophages.29 Therefore, we next tested whether IL-15Rα is also expressed on monocytes. Figure 3F shows that surface expression of IL-15Rα can be readily detected in Txb21+/+ but not Txb21−/− monocytes cultured in the presence of IFN-γ. Furthermore, preventing in vitro the interaction between IL-15Rα and IL-15 blocked the monocyte-mediated appearance of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells (Figure 3G). To further investigate whether IL-15 was sufficient to induce NK-cell maturation, we set in vitro experiments where Txb21−/− NK cells were plated in medium containing IL-15, IL-15Rα-Fc fusion protein, or IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes.20 Figure 3H shows that IL-15Rα can be detected in the surface of Txb21−/− monocytes incubated with IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes but not when incubated with IL-15 or IL-15Rα-Fc (not shown). In the absence of monocytes, IL-15 and IL-15Rα complexes promoted survival and proliferation of Txb21−/− NK cells but not CD27 down-modulation (Figure 3H). In contrast, we observed the appearance of CD27low NK cells when these were cocultured with Txb21−/− monocytes preincubated with IL-15/IL-15Rα-Fc complexes. Altogether, these results suggest that T-bet and IL-15Rα expressed by monocytes play a critical role in promoting terminal differentiation of NK cells.

CD11bhiCD27low NK cells are recruited to the tumor site and reject MHC class I-negative tumors

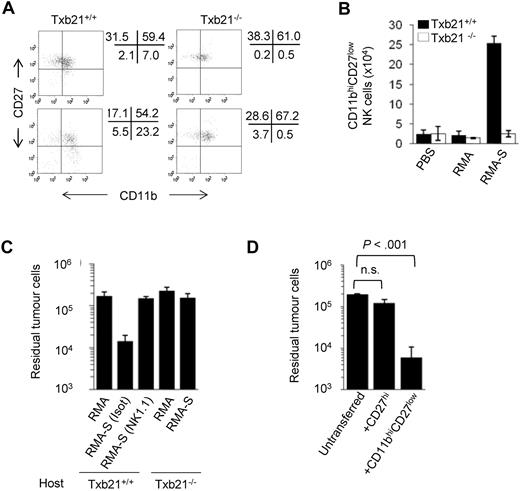

Whether NK-cell subsets defined by CD11b and CD27 expression have distinct roles on tumor immunity remains poorly understood. Because CD11bhiCD27low NK cells express high levels of Ly49 receptors recognizing MHC class I ligands,3 we hypothesized that they could be involved more specifically in the rejection of MHC class I-negative tumors. To test this hypothesis, we used a well-established in vivo model of tumor rejection that depends on NK cells and their recruitment to the peritoneum.30 Recruitment and activation of host NK cells occur after inoculation of tumor cells, provided that the tumor cells lacked critical host MHC class I molecules. In both Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− mice, most peritoneal NK cells are CD11blowCD27hi or CD11bhiCD27hi (Figure 4A). After the injection of MHC class I-negative RMA-S cells, but not MHC class I–positive RMA cells, the proportion (Figure 4A) and absolute number (Figure 4B) of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells greatly increased in the peritoneum of Txb21+/+ mice 48 hours after tumor challenge. In contrast, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells were not detected at the tumor site of equivalently challenged Txb21−/− mice, ruling out the possibility that the CD27hi to CD27low NK-cell transition occurs during antitumor responses. To evaluate the ability of recruited NK cells to clear tumors, NK cell–sensitive RMA-S cells were coinjected with the same number of NK cell–resistant RMA cells as a control. Figure 4C shows that Txb21+/+, but not Txb21−/−, mice rejected RMA-S cells. As expected, the response in wild-type animals was lost after the administration of NK cell–depleting anti-NK1.1 antibodies.30

Txb21-deficient NK cells fail to reject MHC class I-negative tumors. (A) CD11b and CD27 expression in peritoneal NKp46+CD3− NK cells in Txb21+/+ (left panels) and Txb21−/− (right panels) mice injected with RMA (top panels) or RMA-S (bottom panels) 48 hours after tumor inoculation. (B) Absolute CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell number (mean ± SD) in the peritoneum of tumor injected mice from 2 independent experiments with 5 mice per group. (C) RMA and RMA-S tumor cells were labeled with CMTMR and CFSE, respectively, and coinjected into Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− C57BL/6 mice. Forty-eight hours after tumor challenge, peritoneal cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE and CMTMR. Data are mean ± SD residual tumor cells of 3 independent experiments, including 3 mice per group. (D) A total of 2 × 105 RMA-S-CFSE tumor cells were injected into Txb21−/− mice as in panel C, and mice were transferred intravenously with spleen CD27hi or CD11bhiCD27low NK cells enriched from Txb21+/+ mice. Forty-eight hours after tumor injection, peritoneal cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE. Data are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments, including 4 mice per group.

Txb21-deficient NK cells fail to reject MHC class I-negative tumors. (A) CD11b and CD27 expression in peritoneal NKp46+CD3− NK cells in Txb21+/+ (left panels) and Txb21−/− (right panels) mice injected with RMA (top panels) or RMA-S (bottom panels) 48 hours after tumor inoculation. (B) Absolute CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell number (mean ± SD) in the peritoneum of tumor injected mice from 2 independent experiments with 5 mice per group. (C) RMA and RMA-S tumor cells were labeled with CMTMR and CFSE, respectively, and coinjected into Txb21+/+ and Txb21−/− C57BL/6 mice. Forty-eight hours after tumor challenge, peritoneal cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE and CMTMR. Data are mean ± SD residual tumor cells of 3 independent experiments, including 3 mice per group. (D) A total of 2 × 105 RMA-S-CFSE tumor cells were injected into Txb21−/− mice as in panel C, and mice were transferred intravenously with spleen CD27hi or CD11bhiCD27low NK cells enriched from Txb21+/+ mice. Forty-eight hours after tumor injection, peritoneal cells were recovered and analyzed by flow cytometry for CFSE. Data are mean ± SD of 2 independent experiments, including 4 mice per group.

We next investigated the overall anatomic distribution of NK-cell subsets in tumor-bearing mice. The peritoneal injection of RMA-S induced a reduction in the proportion of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells in the spleen concomitant with an increase in the peritoneum (supplemental Figure 6A). Furthermore, adoptively transferred spleen CD11bhiCD27low NK cells migrated to the peritoneum of mice injected with RMA-S cells but not the peritoneum of mice challenged with RMA cells or to peripheral lymph nodes (supplemental Figure 6B). Notably, the adoptive transfer of highly purified spleen Txb21+/+ CD11bhiCD27low but not CD27hi NK cells restored the ability of Txb21−/− hosts to control RMA-S growth (Figure 4D). Together, this set of experiments underlines the relevance of the CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell subset in controlling the growth of NK cell–sensitive tumors developing in the peritoneal cavity.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a functional interaction between NK cells and monocytes has profound implications in the NK-cell differentiation program, leading to the generation of NK-cell subsets relevant to control tumor growth. We have shown that the NK-cell differentiation program cannot be completed in the absence of T-bet because of a checkpoint between CD27hi and CD27low stages, and we propose monocytes as a key player in overcoming the defective NK-cell development observed in Txb21−/− mice. We also show that monocytes deliver T-bet-dependent signals, including the expression of the IL-15Rα chain and IL-15 trans-presentation, for Txb21-deficient NK cells to continue their program of differentiation. The impossibility of rejecting MHC class I-negative tumors by Txb21−/− mice was restored by adoptive transfer of CD11bhiCD27low NK cells, thus highlighting the relevance of this NK-cell subset in controlling malignancy.

Recently, the basic leuzine zipper transcription factor E4bp4 was identified as the master regulator of NK-cell differentiation as E4pb4-deficient mice completely lack NK cells.31 Our data suggest that other transcription factors may help to identify check points of functionally distinguishable NK-cell subsets and provide further support for a model where peripheral NK-cell differentiation can be monitored by the expression of CD11b and CD27.3,4,32

Previous studies underlined the relevant role for DCs and macrophages in promoting NK-cell survival29,33 and homeostatic proliferation.12 The reduction in the proportion of splenic NK cells after the AP20187-induced depletion of CD115+ monocytes and macrophages in MaFIA mice reinforces the current idea that interactions between myeloid cells and NK cells are necessary for NK-cell maintenance. Notably, AP20187 treatment impacted the overall distribution of NK-cell subsets in the spleen with a strong reduction in CD11bhiCD27low NK cells. Reciprocally, CD11bhiCD27low NK cells increased when wild-type animals were administered with CSF-1, a cytokine that promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and survival.34 Furthermore, our in vitro experiments demonstrated that monocytes can drive NK-cell terminal differentiation, but it does not exclude a role of other myeloid, Txb21+/+ cells. New genetic models specifically targeting these subpopulations will allow the dissection of cellular interactions required for NK cells to complete their differentiation program.

Several lines of evidence support the idea that expression of T-bet in NK cells may not be sufficient to complete the CD11bhiCD27hi to CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell transition. Indeed, CD11bhiCD27lowTxb21+/+ NK cells are barely detected in mice where IL-15Rα expression is restricted to CD11c+ DCs33 or in mice bearing lineage-specific deletion of IL-15Rα in CD11c+ DCs, in macrophages or in both,29 suggesting that NK-cell terminal differentiation requires extrinsic inputs. Our data and previous reports demonstrate that Rag2−/−-dependent21 and γc-dependent (this study) lymphocytes do not modulate terminal NK-cell differentiation. Instead, our results are consistent with a role for spleen monocytes, anatomically distributed in the same niche as spleen NK cells, in facilitating the CD11bhiCD27hi to CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell transition. The addition of cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-15) in the in vitro culture medium of sorted Txb21−/− CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells cannot by themselves modulate this step, indicating that a NK/monocyte cell-to-cell contact is required. Importantly, expression of T-bet and IL-15Rα in monocytes is determinant in modulating the CD27hi to CD27low NK-cell step, regardless of T-bet expression in NK cells. It should be noted that, under the in vivo and in vitro conditions tested here, the frequency of Txb21−/− NK cells that differentiate from CD27hi to CD27low stage remains lower than the Txb21+/+ counterparts, suggesting that expression of T-bet in NK cells may still be required to complete fully their differentiation program. The ectopic expression of T-bet retrovirus in CD4 Th2 T cells, which do not normally express T-bet, induced surface expression of CD122 (IL-2Rβ chain),35 and it has been shown that CD122 is a direct T-bet target gene in T cells.36 Nevertheless, whether T-bet directly targets any of the IL-15/IL-15R gene components in monocytes and whether expression of IL15/IL-15R molecules IL-15 is directly or indirectly modulated by T-bet remain to be determined.

There is not a clear consensus as to whether functional specialization among NK-cell subsets exists. The infiltration of NK cells appears to have a prognostic value in human carcinoma malignancies as a higher amount of NK cells correlates with a better prognosis.37 However, whether specific NK-cell subpopulations infiltrate tumor masses is unclear. Several studies have identified a predominant presence of CD56brightCD16− NK cells, the probable counterpart of mouse CD27+ NK-cell subset,38 in nonsmall lung carcinomas39 and in pancreatic metastatic lesions.40 Other studies have observed CD57+ NK cells highly represented in squamous lung cancer37 and colorectal41 and gastric42 carcinomas. In the mouse system, gene expression profiles4 and functional studies3,4 do not allow the attribution of unique functions to CD27hi and CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell subsets. Our data show that CD11bhiCD27low NK cells migrate efficiently to inflamed tissues to restrain tumor growth. Cell migration depends on the functional expression of chemokine receptors; thus, a division of labor based on the expression of chemokine receptors may be proposed. Indeed, CXCR3 and CX3CR1 are expressed exclusively on CD27hi and CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell subsets, respectively,25 suggesting that different NK-cell subsets may be independently recruited into distinct inflammatory settings. The tumor-induced specific recruitment of CD11bhiCD27low NK-cell subset reported here and the defective antitumor responses described in CX3CR1-deficient mice43 support this idea. It should also be considered that the tumor microenvironment, preferentially enriched for CXCR3 ligands rather than CX3CR1 ligands, and the anatomic location of the tumor, may dictate the recruitment of CD11bhiCD27hi NK cells44 or CD11bhiCD27low NK cells (this study). The experiments of our study provide clear evidence for a division of labor among NK-cell subsets and demonstrate that incomplete NK-cell differentiation observed in Txb21-deficient mice may lead to a deficit in effector antitumoral NK-cell subsets. Furthermore, our findings may also explain the increased NK cell-dependent incidence of pulmonary45 and hepatic46 metastasis reported in splenectomized mice.

Previous dissection of NK-cell biologic differentiation and function has been complicated by the lack of deficiency models selectively deleting defined NK-cell subsets. We propose that the expression of T-bet on monocytes is a critical determinant in the functional differentiation of NK-cell subsets relevant to control tumor outgrowth. The intellectual challenge is to understand how the various NK-cell subsets regulate defined functions and how the hematopoietic compartment shapes NK-cell maturation versus survival. Understanding the intricacies of NK-cell development will help appreciate how various NK-cell subsets are generated and participate in antitumor immunity, ultimately offering opportunities for selective intervention.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Francesco Colucci and Randolph Noelle for the critical reading of the manuscript, Jordi Ochando for discussions, and María Hernández-Fuentes for advice with statistical analysis.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (31-109832; A.M.-F.) and the Medical Research Council United Kingdom (G0802068; G.M.L., A.M.-F.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.S., N.P., C.L., and T.W. performed research and analyzed and interpreted data; N.v.R. and A.H. provided reagents and tools; T.W., F.G., and G.M.L. provided essential advice; A.M.-F. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and commented on the draft versions of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alfonso Martín-Fontecha, Medical Research Council Centre for Transplantation, Guy's Hospital, Great Maze Pond, SE1 9RT London, United Kingdom; e-mail: alfonso.martin-fontecha@kcl.ac.uk.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal